An Investigation of Canadian Identity Through Literature

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

on “wanderlust” or whatever

This post was inspired by this current time of year when people of all kinds are eagerly announcing that they’ve “caught the travel bug” or are “going to find themselves” in some ~exotic~ locale.

To this day, I often find myself deeply uncomfortable or struggling to talk about how the summer after my second year went, for a multitude of reasons. First because, well, it’s hard to encapsulate in words how much it changed me. But the second, perhaps more salient reason is that I don’t want to give the impression that the only way to learn more about yourself and the world around you is to ~travel~.

This idea of “wanderlust” or whatever rubs me the wrong way for a number of reasons. Most of it has to do with the fact that it’s incredibly elitist, particularly in regard to the financial accessibility of travel (the other part probably has to do with the weird colonial fetishization of non-western countries as “exotic”). Not only is travel costly in most situations, but it also represents a significant opportunity cost for people who need a steady income to live. A backpacking getaway through Southeast Asia might sound like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, but to people who need to work to pay for school, the time away represents a major loss of potential income. Not to mention, not everyone works a job where it is possible to take extended periods of time off without jeopardizing their job security. Overall, someone’s ability to travel is often determined by larger, structural factors that you can’t control, so it’s not only useless, but also incredibly insensitive to laud travel as the key to self-discovery or knowledge about the world.

So where does that leave us, really? Well, it depends on who you are. As someone who is firmly (and gratefully) on the other end of the travel spectrum this year, I think it’ll be hard not to fall into self-defeating thinking. But I’m looking forward to finding out more about the city that I live in (Hamilton) and hanging out with friends and family, and spending some time with myself. What’s more, I’m excited to spend more time reading, which is probably my favourite way of learning. As characters like the lawyer in Chekhov's The Bet show, it is entirely possible to discover the world from the comforts of one’s own home (though I would hope that your situation is less confining than his).

And what if you’re jetting off on some spectacular travels this summer? Awesome! I’m glad that the stars have aligned and you find yourself in this position. What I hope is that you have an exceptional time, but that you also remember that the people you are leaving behind will also change and grow too. Too often when heroes like Odysseus embark on brave new adventures, they return home expecting their loved ones to be exactly the same as they once were. But the truth is that often, those who remained at home (just like Penelope) have developed over time in their own right as a result of their own own experiences, which deserve their own respect.

Ultimately, there is no one right way to grow yourself or learn more about the world around you. All I can hope is that we are a little more sensitive towards those around us regardless of the path of self-discovery that we choose to embark on. Stay safe, be kind, and love deeply.

0 notes

Text

The pen is mighty, but hard to wield

Writer’s block was been eating me alive for the majority of this trip (along with the travel blues, but more on that in the next blog post) - I never realized how difficult it is to produce something inherently intimate (it did come from your brain, after all!) and put it out into the void that is the internet (or the world generally), not knowing how it’s going to be received, and having to be okay with that.

This feeling can be super overwhelming, which is why I think writers are incredible people for being able to overcome it. Yet a common thread that I’ve been seeing across the country is that they can hardly ever make a decent living from accomplishing what to me, often seems like the impossible. And so, I have to ask, WHY?

Why is it that we get so frustrated when our five monthly articles on the New York Times run out? We feel accosted by the popups that come up on our favourite online article sites that ask you to subscribe, or donate, or in some cases, turn off our ad blockers. On the other hand, most of us would pay money to go see a film, for admission to a museum or art gallery, or to have our caricature done on the street. What makes writing so different in the sense that people are less willing to shell out cold hard cash for it in comparison to more “hard,” science-based skills like engineering or medicine?

I’ve thought a lot about this question throughout the creation and execution of this project, and the best explanation I can come up with has to do with with a scientific concept called “activation energy.”

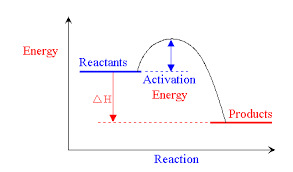

Activation energy is a term used to describe the minimum energy which must be available to a chemical system with potential reactants to result in a chemical reaction. It is commonly depicted as a hump in an energy graph that a system must overcome in order for things to happen. My theory is that this concept of minimum energy required for “success” (a reaction) can also be applied to fields or study or specific skills, including the skill of writing.

For many, we are lucky enough to live in a society where most people read and write at some basic level. As a result of this, basic economic reasoning causes many people to believe that the skills needed to write are not very valuable. There is a low barrier of entry, hence the issue of compensation. However, what most people don’t see is the high activation energy required for you to master the art of writing - yes, everyone can put words on a page, but actually stringing them together in a way that conveys a message in a nuanced way requires strict discipline, a firm grasp on both grammar and syntax, and also a deep understanding of literary devices.

In comparison, skills required in the science often seem opaque and undecipherable to the general public, as they rely on the understanding of technical jargon that is not accessible to a layperson. In this case, the barrier of entry is high, which creates value and demand for scientific skills. However, something that is frequently overlooked is the fact that once these skills are developed, building on this knowledge is fairly straightforward. Mastering the sciences has a low activation energy, as it just requires innovating on a central dogma that is already established and that you have been indoctrinated into from an early point in your scientific career.

On the other hand, literature is always changing, as it is created by people, who are always changing and learning to tell stories in different ways. That’s what makes it difficult to do, but also extremely rewarding.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that (in typical Arts and Science fashion) neither the skills required for literature nor science are more difficult or important or than one another - they are just different in their barriers of entry and activation energies. Writers deserve to be fairly compensated for their work in the same way scientists do, and should also carry the same prestige.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

And so, she resurfaces

At around this time last year, I heard back from the Renaissance Award selection committee about a decision that would culminate in one of the most incredible summers of my life.

As such, I think it’s only appropriate to provide an update on what I’ve been up to since I got back from my cross-country travels! Getting back home was an both a reassuring and overwhelming experience - I was able to squeeze in only a few more interviews until orientation and the whirlwind that is school started in earnest. In hindsight, it was probably a good idea to not think about this project for a few months, as towards the end of August I was feeling a great deal of burnout, with my mind being occupied with nothing but interview and ethics and all of the fun things involved in long-term projects (more on this later) for the better part of a quarter of a year (even longer, if you count the amount of planning and grant-writing that went on to make this trip happen).

Nevertheless, I am back for the foreseeable future, as I’ve been fortunate enough to continue working on this project through an Individual Study with my faculty supervisor. For the next little while, I’ll be sharing a series of reflections on my experience here on the blog, and providing updates on the project itself.

I’m happy to say that after what was a truly exhausting amount of administration, email tag, and spreadsheeting that I have completed and logged exactly 202 interviews with authors all across 10 provinces. I’m incredibly grateful to each and every person who contributed to my experience this summer and can’t wait to transcribe and analyse all of my data!

1 note

·

View note

Text

The politics of literature

Hello! I have not been active on this part of the interwebs lately, and for that I must apologize - Nova Scotia was a province jam-packed with authors, and PEI just flew by in a very rainy, overcast blur. I’ve also been suffering from a bit of writers’ block, or more accurately, writers’ crippling-self-doubt-about-every-word-you’ve-ever-penned. Nevertheless, I’m back at it again with a political science student’s take on the label, “Canadian literature.”

CanLit, like many terms that have to do with national culture, is a phrase that is inherently steeped in the complex relations that make up identity politics. Like I mentioned before, I think that national literature is an excellent way to take a peek into Canadian culture and/or Canadian identity, but with some reservations. In constructing and applying the definition of Canadian literature, there are certain political aspects to be considered. By virtue of defining of something, other things must be left out, and whether intentional or not, these omissions can have important ramifications. In the field of political science, this examination of the power of definition and its effect on who gets to speak and be heard is frequently associated with the postmodernist and post-structuralist schools of thought. In the spirit of these movements (and really, because I’m an ArtSci that doesn’t know how to approach things without being interdisciplinary), I’d like to pose and examine a few questions that attempt to address the power dynamics behind the “CanLit” label.

What is the traditional canon of content defined by CanLit?

I’ve talked about this briefly before, but the traditional canon of CanLit hearkens back to an era that included authors like Alistair McLeod, Farley Mowat, and Hugh MacLennan, who primarily wrote about the land, and the daily struggle to survive against it. Perhaps the most iconic work surrounding the label of CanLit comes from literary icon Margaret Atwood, who argues in Survival that the central image in Canadian literature is “victim” (unlike its British and American counterparts, “island” and “frontier,” respectively). For its time, Survival really did seem to capture the majority of the narratives that were coming out of Canadian authors, but times have changed since then. Struggling against nature isn’t one of the primary concerns for many of Canadians as our country becomes increasingly urbanized. In many ways, the once-unique (and somewhat even exotic) city landscapes that made Mordecai Richler so famous in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz are now more common than ever. So why hasn’t the canon of CanLit changed with the times? Why are we still so hung up on writing about the land and our fight against the wilderness?

The answer, like most regarding this topic, are unclear. On one hand, it is incredibly difficult to deny the effect that landscape has on Canadian literature and Canadian art as a whole (the Group of Seven). On the other, is our obsession with landscape really any different from the fascinations that other countries have their geography? Perhaps not. Another interesting point to note is that contemporary novels have a tendency to be backwards looking (I’m thinking of works by Boyden or even Findley) - it’s tough to write a book that deals with things that are happening in the moment, and much easier to look at the past with hindsight being 20/20. Often, works that do actively deal with the present aren’t well received when they are published; rather, they become best-sellers after the fact (for example, The Great Gatsby was a novel focused on the excess of the 20′s that Fitzgerald was living in and was not terribly well received until much later). As well, it does seem that despite the juggernaut that is the “Canadian nature narrative,” stories are emerging from our nation that aren’t just about the land. And this might be for the better - especially when you consider the diversity in our modern day nation, the dominant, mostly white settler “struggle against the wilderness” story arc just doesn’t seem to cut it any more.

What genres are considered CanLit?

Interestingly enough, something that I’ve noticed about Canadian literature is that it is quite focused in its scope. It encompasses mostly fiction that is for adults - it is quite rare that we hear of a children’s book or YA novel that is lauded for its distinctive Canadian flair (although if you’re looking, I highly recommend Andy Jones’ children’s books which are retellings of Newfoundland folktales and as true a representation of Canadian literature as I’ve ever seen). This might find itself rooted in the perception that non-adult literature is “less than” because it can’t possibly deal with complex issues; as if any richness would be lost on its readers who “just wouldn’t understand”. I simply ask proponents of this view to read Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson, or any of Jacqueline Wilson’s work and reconsider their views.

What’s more, the CanLit label mostly includes Literature (emphasis on the capital L), which is to say that genre fiction such as sci-fi, romance, or horror is excluded from the canon. This view is perhaps most acutely summarized by Margaret Atwood’s vehement resistance to the label of “science fiction” when considering her works The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake. She asserts herself as a “speculative fiction” writer (the merits of this distinction is the basis of another project entirely), and perhaps for good reason. If she were earlier on in her career, the label of “science fiction” on her work might have excluded her from consideration within Canadian literature due to the inherent bias against genre fiction. Another consideration might be the inherent accessibility issues of Canadian Literature; often the production of what falls within the canon of Canadian literary fiction requires some degree of formal academic training. This means that authors of particular backgrounds might stand to have some disadvantage, and forms of experimental writing might be discouraged.

Who is considered a Canadian author?

Another point of contention within Canadian literature is who gets to be considered a Canadian author - given this globalized age, citizenship is no longer a reliable indicator of an author’s identity. Many factors have to be considered, such as whether or not the author was born in Canada, if they’ve resided in Canada for long periods of time, or if they write about “traditionally Canadian” things. Increasingly, the label of CanLit has had to expand from “born and raised in Canada, writing about Canada” in order to accommodate writers like Michael Ondaatje (not born in Canada, living here now, sometimes writes about Canada), Mavis Gallant (born in Canada, has lived most of her life in France, writers about Canada), or Lawrence Hill (born in Canada, lives in Hamilton, doesn’t really write about Canada). This expansion also marks the potential for the argument about who qualifies as a Canadian author (and subsequently, what is considered Canadian literature) to become increasingly semantic.

What’s also interesting to examine is who gets called a Canadian writer within Canada. Some writers, like Margaret Laurence, are considered “Canadian,” while others, like Michael Crummey, are more frequently associated with a regional identity first, such as “Newfoundland writer” or “French-Canadian writer.” From what I’ve seen, this distinctly happens with reference to an anglophone Ontario-centric point of view; writers from Toronto hardly identify as “Ontario writers”. In fact, it is rare to come across the title of “Ontarian writer” unless it has been modified to indicate a “Northern Ontarian writer” - this level of specificity suggested that Canadian literature is not only Ontario centric, but geared mostly towards populous cities such as Toronto or Ottawa (the Golden Horseshoe Region).

Who gets to make these definitions, and who benefits from all of this?

So now that we’ve given some thought to some definitions, it might also be helpful to think about who gets to decide what is considered Canadian literature/who is considered a Canadian authors. For the most part, my interviews have revealed that authors don’t really sit down intending to write the next “great Canadian novel” while thinking about how their identity is going to manifest in their work. Many are content to just write the stories they think should be written and have others do the labelling for them. Sometimes this comes in the form of academics and their formal analysis of literary works. Other times, a whole other dimension of gatekeeping needs to be considered: publishers. As consumers of literature, readers often forget that what is being published isn’t necessary indicative of what is actually being produced by writers; rather, it’s a collection of works that publishing houses expect to sell at the end of the day.

With so many different stakeholders, it can be difficult to see what the ultimate benefits of having firm boundaries around the genre of CanLit are. For authors, it might not be helpful at all, as it can box them in and limit what stories are being told. Yet for academics, the label of Canadian literature facilitates more cohesive analysis that is clearly defined by boundaries. Without a limited scope, teaching CanLit can be exceptionally difficult when syllabi take on a life of their own. The same goes for publishers - in the 60s and 70s when Canada Council for the Arts was making a concerted effort to establish a Canadian literary scene, it made sense to be selective about works that could be considered CanLit. Cultivating a common narrative among Canadians provided both a national literature and a national identity.

But ultimately, in these changing times, I would argue that the Canadian people are experiencing the greatest impact from a rigid definition of CanLit, and not necessarily in positive way. When considering our current level of diversity and how it can only be expected to rise in the coming years, it seems a shame that our national writing should remain stuck in a different era. Reading still remains a big way in which Canadians learn about themselves, but also each other. It is how we connect over huge geographic distances and through generations. In many ways, literature is how we preserve our past, recount our present, and envision our future; yet with the rise of globalization (and subsequently, immigration), these processes are becoming increasingly complex. This is why now more than ever, we need to see ourselves and our multitudes being accurately represented in our literature.

1 note

·

View note

Link

I was on CBC Charlottetown chatting about my project if you’re interested in checking my interview out!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts from the easternmost point in Canada

I’m going to begin this post with a few potato quality phone photos that I took when I was able to make it out to Cape Spear, Canada’s easternmost point (thanks Charlene!).

I don’t know that you could do this place justice even with the best cameras known to mankind - there’s just something about standing on the rocks, looking out through the gentle layer of fog to see if you can catch a glimpse of Signal Hill, kilometres ahead, that gets lost through a camera lens.

Photos can’t really capture the sound of the waves breaking against the rocky shoreline, something that is both soothing but also a very vivid reminder of the fact that the North Atlantic is not to be trifled with. It’s certainly very different from the warm and friendly waters that can be found in the Caribbean, where the waves meet sandy beaches that are filled with sunbathers. This ocean feels much more powerful and dangerous, but still maintains a turquoise colour at the rocks that hints at its relation to its southern cousin.

My time in Newfoundland was just under a week, but it feels like so much longer - time seems to flow a little bit slower here by the ocean in St. John’s. It’s certainly a city that isn’t particularly conducive to someone like me, who refuses to learn how to drive (I paid $35 for a government issued ID card just so I wouldn’t have to get a drivers’ license). I spent most of my time walking around or accepting a ride from the wonderful authors that I interviewed, as the transit here isn’t phenomenal (insert TTC joke here). To be honest, it was actually kind of fun - definitely a good way to get some exercise and see the city.

It was definitely colder than I expected when I landed in the city - for the few days that I was here, it didn’t get any hotter than about 15 degrees, but I kind of like things a little colder, so no complaints here. And however cold it was, the warm people certainly made up for it. In my short experience, Newfoundlanders are incredibly nice and welcoming people; this is a place where people greet strangers in the street and are the first to offer help when you seem lost or are looking for something. I really feel at home here even after only a small period of time and am really sad to be leaving.

There’s also a great sense of pride from Newfoundlanders about being from this place - something that I learnt here is that Newfoundland and Labrador didn’t join Confederation until 1949. This means that there are people still alive today in the province that remember not being part of Canada, and this has incredibly interesting implications for Canadian identity and the literature that comes from this place. Local culture is well and alive here in St. John’s, and many people are part of a founder population that can trace its ancestry back to the 1700s. The city itself seems to strike a perfect balance between actively paying homage to its rich historical roots (there are exceptional archives of folklore and folksong here) and changing itself with the times (one word: hipsters). From this, I think there emerges a very strong sense of belonging to a community that translates to a vibrant arts scene. Most writers seem to know one another either personally, or at least by name, and the connections between artist communities are quite strong. Hybrid artists are frequent, and there is a distinct solidarity that is seen within the community (who rallied together when city funding was cut). Overall, it’s a wonderful place to be an artist, but also a person as well.

Someone told me a joke in an interview that goes something like, “Throw a rock in the Rock and you’ll likely hit a writer.” Funny, but also seemingly accurate, and also interesting in its truth. I’m not sure what it is about Newfoundland that produces so many writers (and excellent ones, to boot). Maybe it’s the sense of newly lost independence that manifests itself in a strong desire to assert an identity through storytelling. Or perhaps its the cold, or the physical isolation from the rest of the nation (”I’m going over to Canada” is a common phrase here), or the distinct culture that has developed over the centuries. Personally, I think it’s a mismash of all those things - I don’t think it’s particularly important to parse out a specific conclusion as to why, but rather, to be thankful that I’ve gotten the opportunity to experience this perfect storm of circumstances, even if for only a brief moment.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My fervent defense of Timothy Findley (and really, CanLit/Identity as a whole)

This post is a pseudo-response to a comment that was left on my Facebook status talking about the start of my adventures. Shoutout to Raymond, who gave me a good opportunity to not only retort that Timothy Findley is a Canadian literary icon, but also more seriously advocate for the importance of understanding Canadian literature, and Canadian identity as a whole.

Something that I’ve seen as a general trend in recent years have been the rise of thinkpieces about the death of liberal arts in the context of the current job market. In many of these pieces, Silicon Valley techies argue that the only language university students should be studying is Python, and that our general focus as a society should shift more towards STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields given our technological progress.

Now, I’m not here to pit the arts against the sciences - as an Arts and Science student, I firmly see the importance of both areas, and often see the value in fracturing the binarism. But also as someone who sees herself as more arts than science, I often find myself frustrated by people who think relegating the humanities and social sciences to the backburner is the way of the future.

Yes, technological progress is important. Modern technology has revolutionized the way society has been able to function - people are living longer and more fulfilling lives. Medicine has increased life expectancy and decreased infant death; the advent of the modern printing press made literacy and education more accessible. Not to mention the internet, which has opened new realms of communication and shrunk geographical distance faster than you can say fiber optic cable.

But I guess I’m a romantic at heart when I say none of this would have been possible without the humanities, and in particular, literature. Our idea of modern progress has, is, and continues to be rooted in this idea of hoping for a better future, and acting on that hope. We have achieved because we want to know more about our world and to make it a better place, and this yearning has been captured for years in the stories we tell. From the early legends and myths that our ancestors used to explain the world around them to the speculative fiction of today, we have used narratives to capture what we understand of the world and our dreams about its potential for eons. This dreaming through stories is how we inspire ourselves to progress and reach further and further - it is the lens through which we view the possibilities of the future.

Defense aside, I also think that the literature of a society can be turned inwards to reveal more about itself. What better way to learn about someone than through the stories they tell? Identity is strongly tied to the idea of personal narrative, and this is what I’ve been trying to get at with the content of my project.

As a nation, Canadians are notoriously ill-defined. We are a country of immigrants, living on stolen land, no longer fully part of the British colonial tradition, but not quite as free as our American contemporaries either. Much of our cultural entertainment (especially for those of us living closer to the border, which is to say, most of us) is dictated by our southern neighbours, and whatever doesn’t come from the States often ends up there anyways (I’m looking at you, Justin Bieber, and basically all of our hockey players ever). We have parts of our country that have historically wanted to leave, some who didn’t join until my sister was born (???), and even parts in between. Many regions of Canada find themselves identifying much more strongly with a local culture than a national one. Thus, it is sort of understandable that it’s hard for us to define what it really means to be Canadian, other than hockey and maple syrup and moose (and also milk in bags).

The worst part is that our identity plays no small role in bigger issues. As a political science student, a lack of cohesive Canadian identity has important implications for federalism and national governance. Our diversity is our strength, but also deeply affects problems like economic segregation and inequality, Indigenous rights, and even foreign policy. If we can’t figure out who we are, how can we govern ourselves or even interact with others?

And this is where From Coast to Coast comes in - my hope is that by travelling the country, speaking to authors, and reading loads of local work, I can see if there really is something at the heart of being a Canadian that spans the vast expanse of our country. If there really is a connecting thread between all these different regions and people, it makes sense that it would be in our literature. After all, scholars like Benedict Anderson argue that nations are nothing more than imagined communities, socially constructed by people and enabled by mediums such as printed literature.

Now, I’m not proposing this project as the one-size-fits-all answer to national unity or all of our political problems, but understanding our identity by examining our literature seems like a good start. If we can use our stories to learn more about ourselves, this kind of self-awareness can lead to more purposeful and conscious change for the better. Onwards!

1 note

·

View note

Text

How did I end up here?

Many people have asked me about where I came up with the idea for this project. How, as a student in political science (and occasionally chemical biology), did I find an interest in Canadian literature, of all things?

Well, full disclosure: I’ve always loved literature. Growing up, I loved reading much more than I loved people (luckily, people have now forced a tie). My second home was the library, and I could more often than not be found with my nose buried in a book, transported to the world of Hogwarts or traipsing off on an adventure with Lady Alana. One of the best gifts I’ve ever received was an audiobook recording that my boyfriend made of my favourite children’s book, Matilda, by Roald Dahl. Needless to say, literature has been a big part of my life, but where does the Canadian part come in?

To be honest, most of my first experiences with Canadian lit were quite unassuming. I read Life of Pi growing up like everyone else, but it never really sunk in that Yann Martel was a Canadian (I actually didn’t know until my sister mentioned it a couple months ago). The Handmaid’s Tale was my feminist awakening like it was for many people, but it wasn’t like Gilead was a Canadian place, if even a real one (although it seems in recent times that might be changing for our neighbours to the south). And so, I really only associated the label “Canadian literature” with works like Anne of Green Gables.

This changed the moment I was assigned The Wars as course reading in high school. I’m not sure what it was about this book that captured me. It’s certainly not an easy read - not only does the subject matter require a lot of unpacking, Findley navigates it through shifting narrative voice and the use of really unusual prose. It’s a book that you can read multiple times at multiple stages in your life; each time you pick it up you walk away with another layer of the work that is revealed. Perhaps that was what really spoke to me about it - the novel still has a very special place in my heart.

The Wars catalysed a love for Canadian literature that I hadn’t experienced before. I became increasingly fascinated with Timothy Findley’s work in particular, and wrote my Extended Essay in English, analysing his writing style and how it shaped conflict in his works across genre. Writing the research paper was a wonderful experience, but throughout the course of it I found myself wondering, “Yeah, this is great, but how is it Canadian?”

I never really got an answer to that question specifically, or in its general form as “What makes Canadian literature Canadian?” Instead, it sort of just stuck around in the back of my mind, lingering until my first year at McMaster, when I read Indian Horse by Richard Wagamese.

In the novel, readers follow the journey of Saul Indian Horse, a young Ojibway boy who is taken away from his family and forced into a residential home at a young age. He finds solace in the game of hockey, and it quickly becomes his outlet as he finds his talent taking him everywhere, eventually landing him a spot on a major league team. Wagamese weaves Saul’s narrative across an overlay of constantly shifting landscapes; from his family’s traditional land to the bustling city life of Toronto, hockey becomes a vehicle and a catalyst through which Saul explores and develops his identity. This idea of landscape shaping identity in a Canadian context was the subject of yet another paper I wrote in an attempt at decoding what Canadian literature was all about.

Writing the paper was really the big connector between what were originally just passing thoughts and a concrete investigation. It was also how I ran into a two key players in what would become the project I’m pursuing today. The first would be my professor Dr. Catherine Grisé, who really shaped my project by suggesting that I was onto something with my constant questioning of how Canadian lit is made unique. Although the topic wasn’t something that I was able to address in my paper about Indian Horse, my desire to think big picture started here with the support of Dr. Grisé, who ultimately became my faculty advisor on this project (thanks Dr. Grisé, you rock!).

The second would be Margaret Atwood’s survey of Canadian literature, titled Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature. Reading her work was particularly inspiring, as she argues that Canadian literature is shaped by the notion of survival. Although for the purposes of my paper I was interested in the motif of struggle against the forces of nature, this idea of victimhood as the common thread between all Canadian works intrigued me. It also left me with more questions - what qualifies as a Canadian work? Are only authors that are born and raised in Canada Canadian (what does this mean for people like Michael Ondaatje)? How long do you have to live here before you’re considered a “Canadian author”? Do authors consider themselves Canadian, or do they associate themselves more with regional groups (Maritime, Atlantic, Yukon, etc.)? Is the image of “victim” really at the core of our nation’s narratives? So many, questions, so little time!

So that’s kind of where this whole journey has left me - probably a little out of my league, certainly with more questions than answers, but that’s all part of the fun, isn’t it?

3 notes

·

View notes