Text

Introduction

When I went abroad to the United Kingdom in the summer of 2016, I was a sophomore Honors Student at USF Tampa pursuing a dual-degree in Psychology and English Literature. I was enrolled in two courses during this month long program, Global Perspectives: “Defining Britishness” and Monstrous Fictions: Gothic Literature of Great Britain. I was absolutely thrilled to be going on this trip with my fellow Bulls, especially since it was my first time abroad.

I was also so pleased to visit Edinburgh, Scotland, on my own during my time in the United Kingdom.

0 notes

Text

What does it mean to be British?

Changes in demographic in Britain

Historical Context

Magna Carta --> Empire --> Brexit

Problems to Cohesive Identity

Comments on appreciation of British Culture

(resiliency?)

0 notes

Text

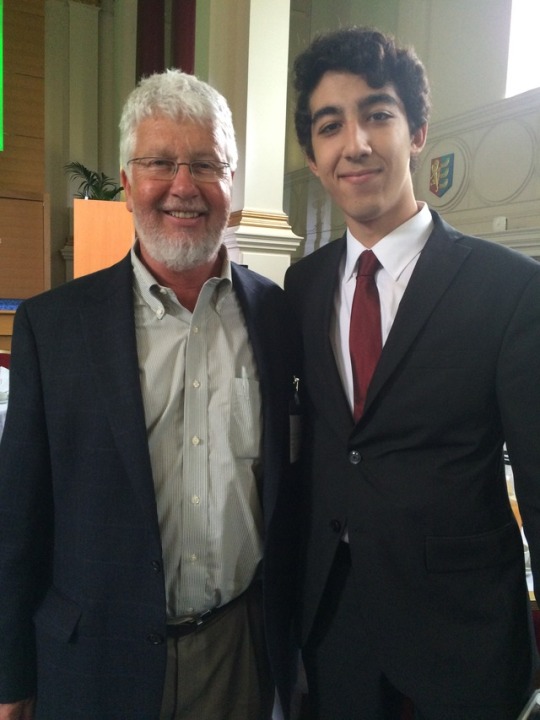

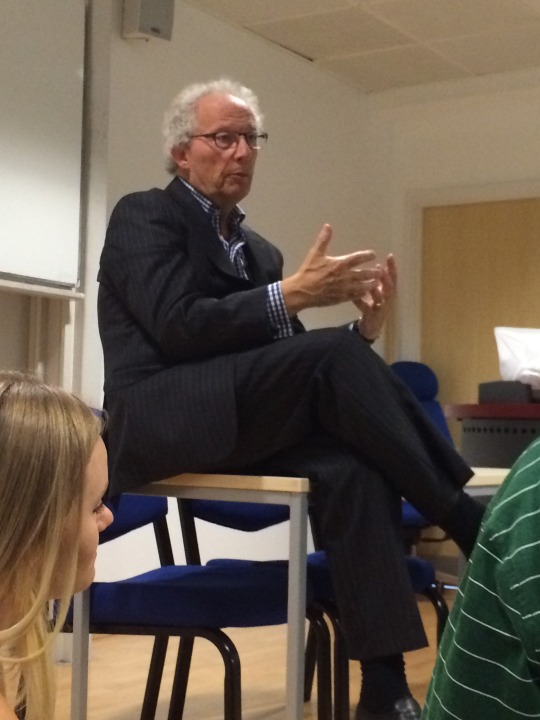

First Minister Henry McLeish

As part of my Global Perspectives course, Dean Adams invited former First Minister of Scotland Henry McLeish to guest lecture on a number of subjects related Brexit and Scottish-English relations.

I was pleased to further discuss these issues with McLeish and some of my peers after the lecture.

Below I are highlights of components of his lecture, our discussion, and my thoughts on how the current global political climate was fostered.

After 9-11, there was a united global effort to tackle the issue of terrorism. After the economic crash of 2008, however, we all failed to respond. This was the catalyst for the growth of discontented democracies present today in which people are treated as consumers, not citizens.

Moreover, there has been a marketization of politics where “big money talks” and not everyone has an equal voice. As a result, many extreme nationalist groups are gaining power in various counties. Examples include the National Front in France, UKIP in Britain, and other radical nationalist movements in Western Europe and America. All encourage authoritarianism, xenophobia, racism, populism, etc. There are no benefits to this.

In regards to Britain specifically... Britain used to rule the world but now it does not have a clear role. To be “British” seems to mean one must subscribe to an abstract notion of sovereignty that is inefficient because there can never be absolute sovereignty in a globalized world. Although initial participation in the E.U. helped ease this trouble, Britain didn’t look to make their own path in the E.U. and rather chose to rely on the success of the United States, with which it had established strong political ties.

When national identity is co-opted by abstract and overzealous rhetoric, politics becomes misleading and it is difficult for any genuine work to be done. The true sources of such systemic problems are never addressed because the public and politicians are too busy trying to solve symptoms of the problem.

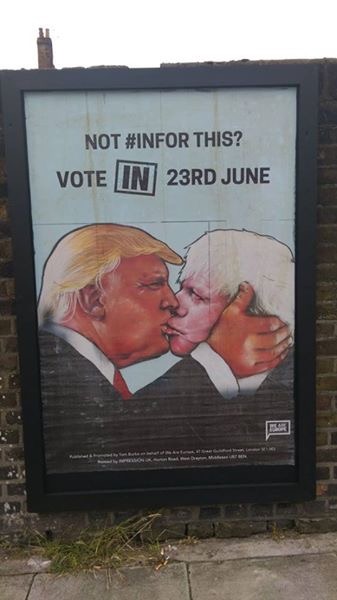

Brexit

Cameron initiated the referendum out of pressure from UKIP and to cater to the ultra-right of his party. An electorate was encouraged to vote based on biased extreme nationalistic rhetoric. Members of the public were essentially provided with an outlet for their grievances: the rest of Europe.

Instead, it led to more consequences:

diminished power

reopened wounds in Northern Ireland and revamped debate about Irish reunification again due to not wanting to share border

reinvigorated efforts for Scottish independence that could lead to a lesser Britain without Scotland

Globalization and Democracy

Market dominance impacts politics in America and somewhat in Britain, and harms democracy in the process. In America, grievances are often blamed on globalization in general. In the U.K., grievances are often blamed on globalization in the form of relations with the E.U.

A healthy democracy depends on citizens who are healthy and able to participate. Yet... we treat our citizens so poorly. For instance, despite having the largest military and being a global superpower, we cannot fill our food bank. Without nonprofit work and the evangelical church system based in the South, few would receive any real assistance. Citizens should not be treated as if they are useful only every two, four, and six years. Unless we tackle inequality and racial divides, “one nation, under God, undivided” will become a meaningless statement. People are not entirely self-made; everyone benefits from public services.

Scottish Politics

The Scottish National Party is an inclusive party soft on immigration with left-wing policies like free tuition. They look pretty liberal but are structured as a coalition of members from the left and right, all of whom are united by a desire for independence. They would likely be the majority party in Scotland if the state were to become independent from the United Kingdom in a similar way to the way that nationalist powers took power in former USSR countries. The SNP is not is not necessarily a problem, but the extreme nationalism shared by some members of this coalition could be if it leads Scotland to follow England’s historical pursuit of isolation.

Conclusion

Many of these points have been simplified in an effort to be concise. There are few key points that hopefully shine through though:

treating citizens like consumers does not lead to effective civic and social participation in society

issues regarding national identity and international relations should be tackled from a systems thinking standpoint

accomplishing goals on a national or an international level requires genuine partnership between national political parties and between different nations

0 notes

Text

Gothic Fiction and its Revelations about British Culture

Before the USF in London program, I had traversed the United States many times but never actually taken my travels abroad. This was my first time staying in a foreign country and it was the perfect first international experience. I was able to fulfill a lifelong hope to see the land that my family originated from and was also able, through my Gothic Fictions course specifically, study English literature while observing the culture and locations that inspired it. The thing I found most remarkable about London, and Great Britain at large, is how tangible history is. I was able to see clashes between the past and present in the architecture on every street. British culture values its history greatly – its past interactions with Europe and the rest of the world influence its national identity and political decisions made in contemporary times. Thus, it is no wonder that there are so many museums and monuments preserving Great Britain’s past throughout the streets of its capital and surrounding areas. By experiencing British culture and viewing into its history, I was able to gain a much deeper understanding of the gothic novels I studied this past summer term than if I had remained in the United States to learn about them.

My favorite excursion was the one in which my class traveled to Strawberry Hill to see the residence of Horace Walpole, the author of The Castle of Otranto and creator of the gothic genre. I’ve written extensively about Walpole and his initial novel for this class, both in a journal entry and for my literary analysis essay, so I won’t elaborate much more excessively about this trip except to mention one thing. Through his renovations of Strawberry Hill House, Walpole preserved the sense of history that is so important to the British people. Not only did he put his own familial stamp on the home, but he also included glimpses into Great Britain’s grander history – eminent rulers and artists are represented in stained glass windows and rooms are modeled off of designs for other important locations such as Prince Arthur’s tomb or Queen Anne’s bedroom.

After the excursion, I noticed potential historical inspiration for some of the plot in The Castle of Otranto. Manfred’s pursuit of Lady Isabella and his rejection of the church when it fails to help him divorce his current wife and remarry reminds me a great deal of King Henry VIII’s scheme to marry his mistress, Lady Anne Boleyn, by establishing the Church of England. I have no scholarly research to back this claim, but merely thought I’d share this errant thought which entertained me.

I enjoyed reading our selected texts in the chronological order in which they were written and subsequently published because it allowed me to analyze trends in gothic fiction over time. Setting, for instance, changed from scenes in crumbling castles and abbeys isolated in distant areas (The Castle of Otranto, Northanger Abbey) to urban slums in the center of crowded London and even the actual human body (The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Picture of Dorian Gray). Much of this change of setting had to due with the influence of Charles Darwin and his publication of the Origin of Species, which outlined the Theory of Evolution. Darwin’s scientific contributions raised fears that humans may not always evolve into something physically and mentally superior. Perhaps one could regress to something more ape-like and primitive, resembling a mammal we might have evolved from as was depicted by Robert Louis Stevenson’s descriptions of Mr. Hyde.

The concept that we can observe evolution also fostered other fears. The reason Hyde was not caught and tried for his crimes was because he was able to swap identities with the respectable Dr. Jekyll. Dorian Gray too escapes lawful punishment; he is not revealed to be a narcissistic and murderous sociopath because his portrait self bears the physical effects (evidence) of his crimes, not his actual body. The idea that a criminal could potentially lurk behind a respectable persona no doubt contributed to the Victorian era interest in the field of criminology and the public’s terror of the infamous Jack the Ripper.

British history is also rife with religious conflict and upheaval as different factions of the Christian church fought for political control of the nation state. As the church went through an evangelical revival in the eighteenth century, many dissenting factions and cults were also revived. This no doubt contributed to an interest in the occult and the representation of supernatural forces in gothic literature. Rapid advancement of science and technology, which a vast majority of the public was not educated in, also found its place in gothic fiction. The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde both deal with practical and ethical issues regarding science and technology. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle investigates the value of the scientific method and Stevenson questions the moral issues of progress, for instance.

I also learned about the influence of imperialism in gothic literature. Tensions and ethical dilemmas between the treatments of different socioeconomic classes were represented in the novels. In Stevenson’s novel, Hyde is able to buy his way out of trouble when he attacks and kills a poor girl from the slums. The police only hunt him when he murders an upstanding member of Parliament. Character motivations are questioned in other works, such as Northanger Abbey, when families look to arrange marriages between a pair of people from different financial backgrounds.

I also gained historical context regarding the gothic works I studied while on the program’s trip to Bath. The resort city of Bath is a location I am familiar with through my study of other British works like Frances Burney’s Evelina or a number of Jane Austen’s novels, including Northanger Abbey. Between the seventeenth and early twentieth centuries, women often traveled to Bath as part of their social functions when ‘coming out’ to society, whether formally or informally. If the peaceful scenery and more relaxed atmosphere of Bath was a standard place for people to travel, it is easy to see why some of the settings of gothic novels and their themes would be so terror inducing to audiences.

This study abroad trip to London was an unforgettable experience that I value enormously not only for its personal value to me but also for the academic knowledge I gained. I learned a great deal more in a month than I would have previously thought possible and staying in the city of London and applying my first-hand observations to my studies all the more enriched my experience studying gothic literature.

LINK: https://lindsay-usf-london.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

Final Reflection

Before departing America for the USF in London program, I had a very limited understanding of British culture and its influence on American identity. My name – Lindsay Margaret Catriona Everest – is about as British as a name can be, reflecting English ancestry traced back to William the Conqueror and more recent Scottish familial ties through my great-grandmother. Despite the few Scottish character traits that seem to be ingrained in my nuclear family and myself, I still was largely ignorant of British culture. If someone mentioned Britain, I’d conjure up cliché images of English landmarks, tea, double decker buses, and pleasure gardens.

While I had traversed the United States many times, I had never actually traveled internationally. My involvement with British culture was only indirect – through anecdotes I heard from family and friends, re-runs of British comedies, and British literature that I had read for pleasure when I was young and now studied in college. Once enrolled in the USF in London program, however, I had the opportunity to fulfill a lifelong hope to see the land that my family originated from and analyze the subtle (or not so subtle) differences between British and American cultures. This course was instrumental in helping me do this as it challenged me to define Britain’s ever-evolving national identity through our journey throughout the varying boroughs of London.

The natural first step in understanding what set Britain apart from America was observing the people of the city I was studying in for one month. London, of course, is not like any other city in the world. It is very complex with thirty-two boroughs distributed between the Inner London and Greater London areas. The underground tube, possibly the largest complex of underground public transportation in the world, does not even reach all of these boroughs. Within this hive, people live packed together. One apartment building can serve as a home to many different people, living on separate floors of the same address. The sheer mass of people crammed within the city makes it almost impossible for one not to encounter thousands of people in a single day. Within my first week staying in London, a few things became apparent about the city and the people that lived in it.

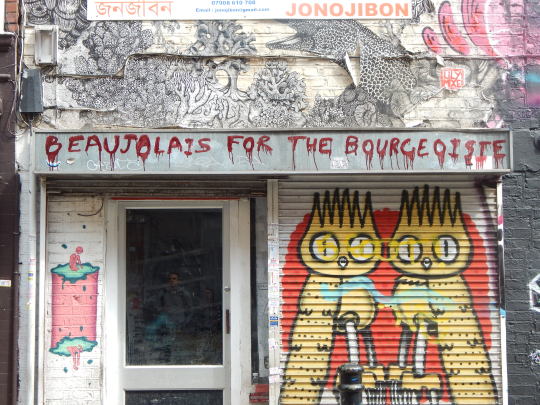

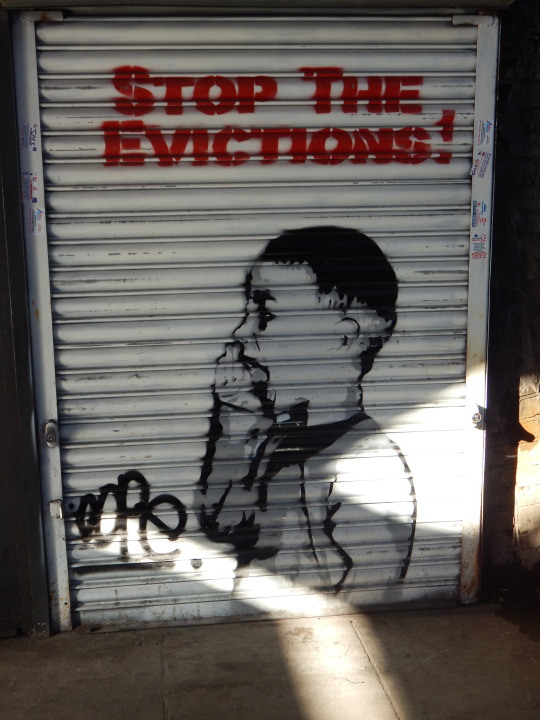

The first thing I noticed was that Londoners, and the British in general, are more conservative in their behavior. This does not necessitate unfriendliness, just a lack of enthusiastic interest in others. Americans find it habitually natural to appear overtly approachable and it is normal to strike up conversations with strangers in confined settings like public transportation in an effort to appear polite and friendly. The British find it more polite to avoid interrupting others or prying into the personal business of others by conversing with them. On a several hour bus ride to Edinburgh, the only things shared between the person riding next to me and myself were a cursory greeting and a mutually beneficial search for outlets. The rest of the people on the bus were rather silent as well. Moreover, sharing one’s affiliations or preferences also seems to be in poor taste. The British do not place bumper stickers on their cars advocating for social causes or indicating their love of a specific football team and, apart from one t-shirt disparaging Nigel Farage and a few cases of street graffiti, I did not see people proclaiming their political leanings outside of an organized protest or event.

British culture is also not as consumer focused as American culture. Aside from the Tube, I rarely saw adverts in public outdoor spaces. Now that I am back in the States, I realize how distracting the constant bombardment of billboards and other ads can be. Not having ads to distract the senses allowed me to focus on other, more important things throughout the day and to observe the city without hindrances. There were no billboards to block sightings of English Baroque style cathedrals, Victorian brick buildings, and gentrified developments. In the middle of one of the world’s largest and most modern cities, life felt organic.

Amidst the marble, brick, and concrete jungle, a great deal can be learned about the city of London and how it has evolved. In the span of one block, one can encounter varying architectural styles that reveal numerous influences on British history whether Norman-Romanesque, French, or other. One can gain a real appreciation for history when it is built along the pavement one walks everyday. I had the chance to see not only the passage of time through different architectural designs, but also evidence of important historical events like the Blitz. Along the Thames, modern architectural designs are prevalent. I was surprised and pleased to learn how much the government invests in design planning. Historic and cultural sites with unique architectural designs are designated for preservation and new developments are regulated to ensure that they represent the globalized and sustainable London of today without clashing with the design of more historic sites.

After my friends and I attended the orientation tour of our residences, Birkbeck campus, and convenient spots for grocery shopping, we decided to head to a pub and delve into British pub culture. Spending ten minutes in a pub was enough to see that the British people are community-minded. In a place where conservatism and privacy is so valued, it was strange to see complete strangers having rows over which football team was superior and clinking pints over goals. Pubs serve as the heart of the community of the city, uniting the Brits in communal pastimes of drinking, watching football, and socializing. This desire for community extends outward from pubs. All sorts of societies, clubs, charities, and institutions are advertised on flyers papered lampposts and street signs.

This community-minded spirit extends to how the British people regard the role of local and national government. There is a certain amount of trust that the government exists to serve the British people and a belief that this investment in the British people helps the nation state in turn. Many services are provided in order to increase the standard of living. The National Health Service, for instance, is based on the concept that everyone has an equal right to healthcare despite how much money they have and that the economy benefits from having a healthy workforce.

Of course, all that I have been discussing so far are mere commonalities – characteristics and values that many British share. Characteristics and values, however, do not a national identity make. A shared commitment to freedom, liberal principles, and tolerance as well as reserved attitudes and community-oriented mindsets help facilitate a bond between the British people but do not necessarily bond the British people to identify with their nation. In other words, these commonalities do not define ‘Britishness.’

This class has challenged me to define what national identity is and examine its worth for a people. Part of the trouble with defining national identity is that it is more of a sentiment than an opinion. It cannot be fostered by the government like national values can. National identity is inherently tied to a nation state’s national story: the history of its political development, the romantic attributes that the nation state works to possess, and the image that the nation state tries to portray to others.

Talking about national identity in an age of globalization is especially difficult because cultures are rapidly changing, challenging previous notions of national identities in many nation states, including Great Britain. The prevailing post-Brexit rhetoric argues “Britishness” can only be applied to those who are white and have had families living in Britain for an ambiguous number of generations; this is ironic considering that Britain is a multicultural nation state today. The capital’s mayor is the son of Pakistani immigrants, the second most iconic British meal is curry, and many boroughs like Brixton are founded on the integration of foreign cultures into British society.

The Brexit debate has highlighted difficulties for Britain in successfully adapting their national identity to their post-imperial status. Without a cohesive national identity, Great Britain now seems to be struggling to agree on the national values it wants to embrace in the 21st Century and the image it wants to portray of itself to the world now that it is no longer a hegemonic empire. This certainly demonstrates the importance of a defined and cohesive national identity.

This trip has additionally made me aware of the similarities between the United States and Great Britain. By listening to the lecture from Foreign Service Officers at the U.S. Embassy and the discussion with Former First Minister Henry McLeish, I learned a great deal about the special relationship between Great Britain and America. Where Great Britain once ruled the world, it now lacks a clear role in the 21st Century. Although the European Union helped ease this transition, Great Britain did not find a new identity in the European Union and instead chose to rely on its relationship with the United States. This eventually led to accepting a supporting role to the United States in international politics, resulting in significant political stress within Great Britain. One example of this, as Henry McLeish mentioned, was Blair’s decision to follow the United States invasion of both Afghanistan and Iraq.

While the British government and people seem painfully conscious of what is going on in America, average citizens here have almost no awareness of Britain. Most Americans come up with one of two conceptions of Britain. Either they imagine it whimsically, a-la Mary Poppins (brick buildings housing intellectuals with quirky humor) or imagine the Britain of King George III that we rebelled against. The few modern references that permeate our culture at large seem to revolve around the royal family and the X-Factor. As the modern dominant political and military superpower, the United States has come to expect Great Britain’s support rather than its leadership.

While Great Britain used to be the hegemonic leader of the world in the 19th Century, today that role belongs to the United States. The flipping of these roles has left Great Britain searching for its new identity within today’s world and our lack of awareness of Great Britain’s history and current identity struggles has left us unable to learn from their experience. We are currently facing a similar debate in the United States as Great Britain did with its Brexit issue. Our current political debate is embedded in questions of our international role and, more importantly, what it means to be an American. Echoes of the Brexit debate can be heard in our current political discourse. This makes our unawareness of the challenges Great Britain faces in establishing a cohesive identity rather foolhardy as we may soon be facing similar internal decisions about our national identity and about the cost or benefit of our international relationships.

I no longer conjure up select English stereotypical images when thinking of Great Britain as a whole. The USF in London program, especially through this course, has exposed me to the brick and mortar of how national identity is built – one neighborhood at a time, one international experience at a time, one generation at a time. Great Britain’s history and its national story are interwoven through the different boroughs, written in its architecture, pub culture, values, and more. My concept of ‘Britishness’ cannot be limited to the shallow representation of national images like the Union Jack and national pastimes like taking Afternoon or High Tea any longer. Weeks later I find myself spending time going over my class readings for my own personal enjoyment and reflection. I’m very much inspired to continue studies and pursue new travel opportunities – both to return to London and traverse new parts of the world.

0 notes