Note

Words like "cervix" and "uterus" are absolutely inaccessible for ESL people though, and "cervix-haver" and "uterus-haver" even more so, both of which I've seen. These are uniquely English word structures and I would think that they are diseases if I didn't know those words already. Saying this as someone who went to a bilingual gymnasium, I only learned the word cervix thanks to being on r/badwomensanatomy or whatever that subreddit is called. I still don't see the problem behind "biologically female" tbh. If that makes you dysphoric you'll obviously be way too dysphoric to get pap smears or mammograms anyways😐 but the first gen immigrants would probably appreciate knowing that they're offered

I think if people don't know what a uterus (or womb) is there are deeper problems at play than trans people.

"___-haver" is not the only way to phrase that in English; "person with ___" is right there. Which is how its also phrased in other languages. From @anomalousmancunt:

#Not to mention that assuming non-english speaking women are too dumb to understand new terms is fucking disgusting#guess what anon. If you're USAmerican then your feminism is at least partially built on the work of latinoamerican feminists#feminists outside of the anglo bubble can understand new language just fine. we build new language always#like literally. it was hispanic feminists promoting an entire new pronoun IN SPANISH (one of THE gendered languages)#you think we're going to struggle latching onto the term PEOPLE?#as IF latam feminists didn't already use terms like 'gente que menstrua' and 'personas gestantes'#argentina had a gender identity law before the USA legalized gay marriage ffs#we don't need you to defend us against the evils of gender neutral language anon

Also, trans people die when they can't get proper gynecological care, so fuck you for acting like that's a cute thing to snark about.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctor red flags:

-Mentions weight loss, exercise, nutrition, mental wellness, before any physical examination/testing

-interrupts you

-tries to rush the appointment

-laughs at you

-says you're too young

-Touches you without warning or asking for consent (common with older male doctors unfortunately, but is becoming less common)

-accuses you of self dxing/mentions dr. Google

-mentions anything about powering through the pain

Do not be afraid to drop a doctor/caregiver and see a new one. Doctor shopping is a term made by ableds who believe every doctor is perfect. Your health is precious and you should only trust those you're comfortable with to take care of it. Do not feel bad about offending the doctor. They do not care. They won't harass you or question you (if they do then that's..probably illegal). I know its hard with some insurances or lesser served areas so don't feel bad if you can't, but if you have the option to do so do not be afraid.

Extra tip: Most doctors will behave themselves if you bring an advocate. Even just having a friend sit quietly will help.

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

btw the term "women's health" to discuss uterine care/menstruation isnt just transphobic, it also keeps up this aggravating idea that the uterus & menstruation are obscene and impolite and need to be kept hidden under flowery vague terms as to not offend any cis men. like trans people demanding the end of gendered language around this stuff aren't just helping trans people, its also just good to normalize calling tampons and pads "menstrual supplies" because thats what they fucking are!!! we should say the words uterus vagina menstruation and we should do it in public and in stores instead of talking about ~women's needs~ and ~feminine care~. trans liberation is fundamental to women's liberation and anti-patriarchal action in general. listening to trans men & people isn't bad for women its good for literally everyone

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

TRANSGENDER DAY OF VISIBILITY DONATION LINKS

it's tdov again, so @ my fellow allies: please use this day to help out & consider donating to charities supporting trans people. if you follow current events (which you should) you know how much this support is needed, so here is a small list of charities I personally donated to & lists others already put together:

the trevor project (not solely a trans charity, but one I regularly donate to)

bundesverband trans* e.v. (as a german one this is another go-to)

transcend australia

a list of 15 trans organizations to donate to

a list of uk trans charities

this list is non-exhaustive, please feel free to share & add more! also remember to keep up your support beyond this one day 💙💗🤍

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome: A systemic review and meta-analyses

Michelle Y. Nabi, Samal Nauhria, [...], and Prakash V. A. K. Ramdass

Abstract

Objective

To estimate the pooled odds ratio of endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome, and to estimate the pooled prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in patients with endometriosis.

Data sources

Using Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Science Direct, ClinicalTrials.gov, Web of Science, and CINAHL, we conducted a systematic literature search through October 2021, using the key terms “endometriosis” and “irritable bowel syndrome.” Articles had to be published in English or Spanish. No restriction on geographical location was applied.

Methods of study selection

The following eligibility criteria were applied: full-text original articles; human studies; studies that investigated the association between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome. Two investigators screened and reviewed the studies. A total of 1,776 studies were identified in 6 separate databases. After screening and applying the eligibility criteria, a total of 17 studies were included for analyses. The meta-analysis of association between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome included 11 studies, and the meta-analysis on the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in endometriosis included 6 studies.

Tabulation, integration, and results

Overall 96,119 subjects were included in the main meta-analysis (11 studies) for endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome, with 18,887 endometriosis patients and 77,171 controls. The odds of irritable bowel syndrome were approximately 3 times higher among patients with endometriosis compared with healthy controls (odds ratio 2.97; 95% confidence interval, 2.17 – 4.06). Similar results were obtained after subgroup analyses by endometriosis diagnosis, irritable bowel syndrome diagnostic criteria, and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores. Six studies reported prevalence rates of irritable bowel syndrome in people with endometriosis, ranging from 10.6 to 52%. The pooled prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in people with endometriosis was 23.4% (95% confidence interval, 9.7 – 37.2).

Conclusion

Patients with endometriosis have an approximately threefold increased risk of developing irritable bowel syndrome. Development and recent update of Rome criteria has evolved the diagnosis of IBS, potential bias should still be considered as there are no specific tests available for diagnosis.

Systemic Review Registration

Keywords: irritable bowel syndrome, endometriosis, systematic review, meta-analyses, functional gastrointestinal disorders

Introduction

Endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are two common medical conditions that markedly affect a substantial proportion of adults and teenagers, and even some menopausal adults (1, 2). Even though they are two distinct conditions with different etiologies, a significant percentage of people experience both concurrently (3). Endometriosis, with an estimated worldwide prevalence ranging from 0.7 to 8.6%, (4) is characterized by the existence of endometrial-like tissue that has been disseminated beyond the uterine cavity. Patients with endometriosis commonly experience menstrual disturbance, infertility, abdominal and pelvic pain, and irregularities with bowel movements (5, 6).

Irritable bowel syndrome, which shares many clinical features with endometriosis, is a gastrointestinal disorder that primarily affects the large intestine, and is characterized by an array of symptoms such as alteration in bowel movements, abdominal discomfort, pain, and cramping (7). The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome ranges from 0.4 (in India and Ghana) to 20.9% (in Singapore), with a pooled global prevalence of 5.9% (8). Moreover, approximately 61% of adults and teenagers who were assigned female at birth are affected by irritable bowel syndrome (9).

Irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis have a significant overlap in symptom presentation due to chronic inflammation thus leading to chronic pelvic pain (10). Endometriosis may even masquerade as irritable bowel syndrome in some patients (11). However, despite these similarities in clinical presentation, a recent nationwide study in the U.S. has shown that endometriosis increases the risk of irritable bowel syndrome approximately threefold (3). Possible explanations for this increased risk include chronic low grade inflammation resulting from mast cell activation, neuronal inflammation, leaky gut, and dysbiosis (12).

It is unclear if endometriosis is an independent risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome. The main purpose of this study was to quantify the association between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome, and to estimate the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in patients with endometriosis through pooled analysis.

Materials and methods

Sources

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and protocols (PRISMA-P) statement (13). The study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (University of York, United Kingdom).1 A systematic search of the following electronic databases was conducted to identify peer-reviewed literature from inception until October 2021: MEDLINE, Science Direct, ClinicalTrials.gov, Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, and Web of Science. Key words or MeSH terms used were “irritable bowel syndrome” AND “endometriosis.”

Study selection

Citation files from the searched databases were imported into Endnote reference management software and duplicates were removed. Using the eligibility criteria, two investigators independently screened titles and abstracts of the studies for relevance. The potential full texts articles were further assessed to be included in the review. Any disagreements between the authors were resolved with a discussion. Inclusion criteria were any observational or experimental studies that investigated both endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome. Studies were included if irritable bowel syndrome was diagnosed by pre established criteria. Endometriosis had to be confirmed surgically, by clinical inspection, or reported as the International Classification of Diseases code for endometriosis. Meta-analyses, reviews, conference summaries, abstracts, case reports, opinions, letters, and animal studies were excluded. There was no search restriction for year of publication or the age group of patients. Articles were restricted to English and Spanish.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted into a standardized data-collection sheet using the following headings: first author name, date of publication, study site, study design, irritable bowel syndrome diagnosis criteria, endometriosis diagnostic criteria, sample size, event rate, and quality assessment score. Two investigators (MN and PR) assessed the quality of all included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), and the overall scores were recorded (14). NOS scale is widely used for assessing quality of each included study in meta-analyses and is based on ranking studies on according to the selection criteria, group comparability and ascertainment of exposure.

Data synthesis and analysis

Forest plots were generated with Review Manager version 5.4 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, Denmark) and funnel plots were created with JASP statistical software. The primary outcome of the association of irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis in this meta-analysis was performed using the random effects model to produce odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). We conducted subgroup analyses based on diagnosis of endometriosis (surgical versus ICD-9-CM 617.x codes), method of diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome, NOS scores (>6 vs. <6), and a combination of all criteria (endometriosis diagnosis; irritable bowel syndrome criteria; NOS score; and study design). In the subgroup analysis based on all criteria, studies were grouped as having met all criteria (surgical diagnosis of endometriosis, irritable bowel syndrome diagnosed with Rome criteria (15–17), NOS score > 6, and longitudinal studies), or not. This allowed for strong epidemiological evidence for the association between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome.

According to Rome III criteria, IBS patients can be classified into four subtypes and can be useful for treating specific symptoms of the patient. The subtypes include: IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with mixed features (IBS-M) or IBS, unsubtyped. Whereas Rome IV criteria defined IBS as a functional bowel disorder in which recurrent abdominal pain is associated with defecation or a change in bowel habits.

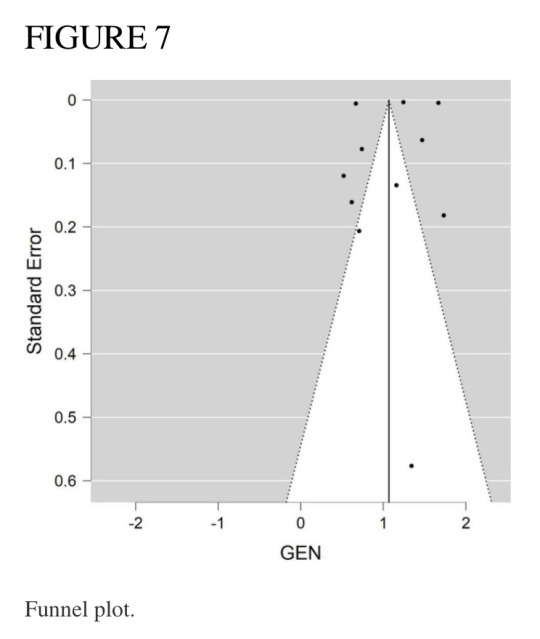

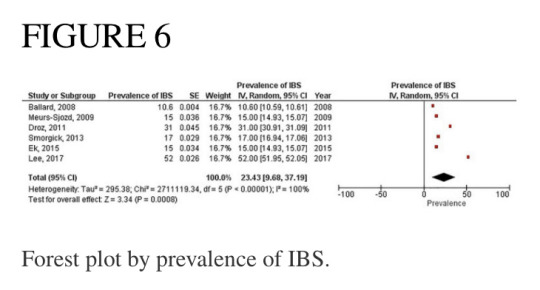

A separate forest plot was generated for the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in patients with endometriosis, for studies that provided only prevalence data. The random effects model account for between-study heterogeneity by weighting studies similarly. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. Values of I2 > 50% were considered as indicative of large heterogeneity (18). We used the Begg’s and Egger’s funnel plot, which is a subjective visual method, to estimate risk of publication bias. A funnel plot that appears asymmetrical suggests publication bias. A p-value of <0.05 for all analyses was considered statistically significant. Although p-values are poor predictors of outcome, all quantitative studies included in our analyses mention p-values in accordance to the AM Stat recommendation.

Results

Search results and study inclusion

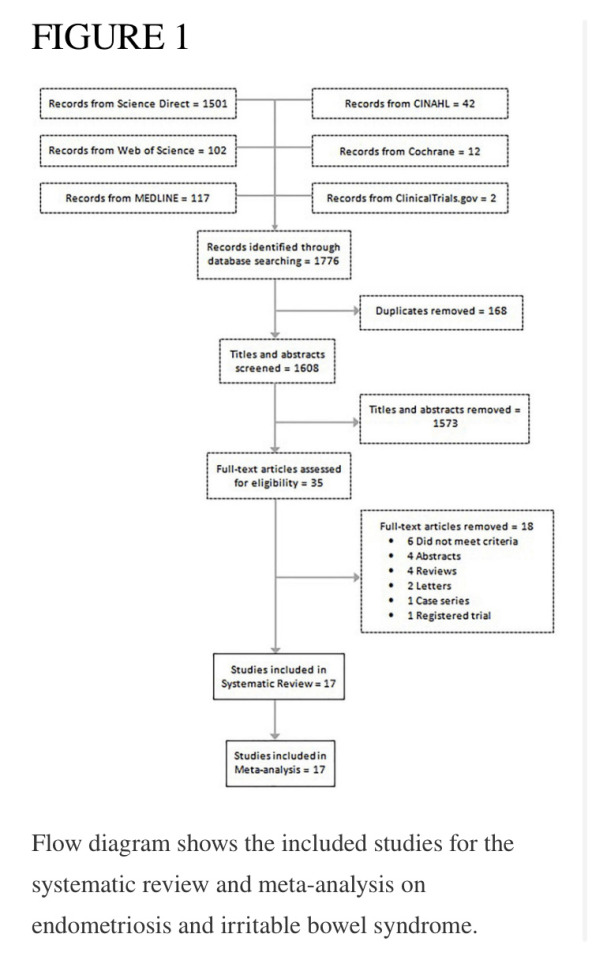

A total of 1,776 studies were identified in 6 separate databases. After removal of 168 duplicates, there were 1,608 eligible studies (titles/abstracts) which were independently screened by two reviewers. Of the 1,608 screened studies, 1,573 did not meet inclusion criteria and 35 full-text articles were reviewed. A total of 17 studies met criteria to be included in the systematic review. Eighteen studies were excluded for the following reasons: did not meet criteria; conference abstracts; reviews; letters; case series; and registered trials. The meta-analysis of the association of endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome included 11 studies, and the meta-analysis on the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in endometriosis included 6 studies (see flow chart in Figure 1).

Study characteristics

Overall 96,119 subjects were included in the main meta-analysis (11 studies) for endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome association, with 18,887 endometriosis patients and 77,171 controls (patients without symptoms). The participants in the study by Ballard et al. (19) were already reported in the study by Seaman et al. (2), thus they were not added to the main meta-analysis twice. The meta-analysis on the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in endometriosis included 6,395 subjects. Almost all articles were published during the last decade, with two exceptions, which were published in 2005 and 2008. Of the 17 studies in this review, the majority were conducted in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Sweden. Table 1 describes the key characteristics of the included studies. Most studies used either Rome II (15), Rome III (16), Rome IV (17), or the visual analog scale for irritable bowel syndrome (VAS-IBS) (20) questionnaires to diagnose irritable bowel syndrome. Endometriosis diagnosis was confirmed either by laparoscopy or laparotomy. Each study had a quality assessment score between 5 and 10 on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (14), with most studies having a score of 7 or greater.

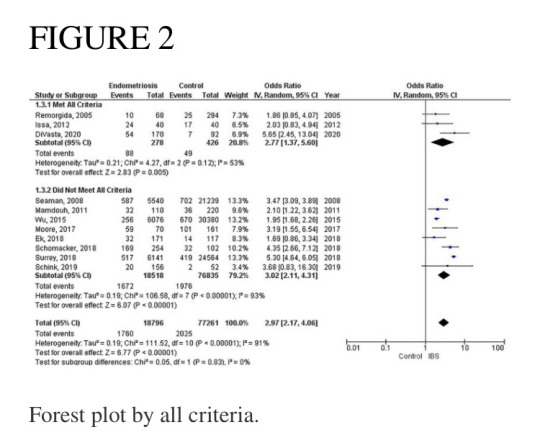

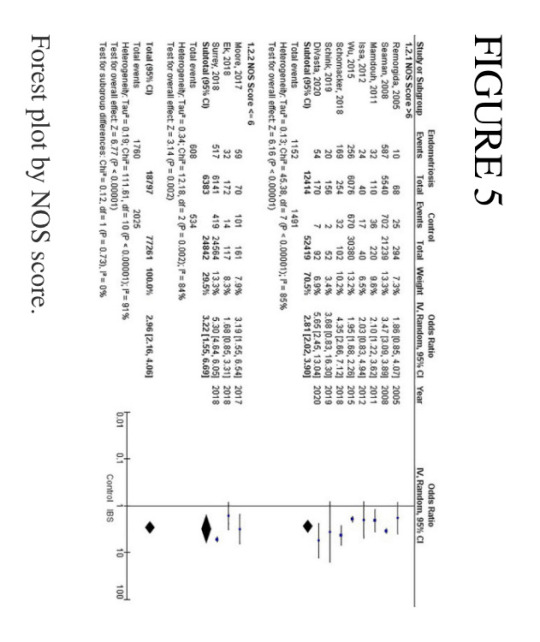

Meta-analysis of studies

Of the 11 studies in the main meta-analysis (1–3, 10, 21–27), most were cohort and case control. Studies were conducted from 2005 to 2020, and sample sizes ranged from 80 to 36,456. In this meta-analysis the pooled odds ratio of endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome was 2.97 (95% CI = 2.17 – 4.06), based on all selected criteria (see details in Figure 2). Odds ratio for the individual studies ranged from 1.69 (26) to 5.65 (10). There was a large heterogeneity in this study (I2 = 91%, [P < 0.00001]). In our subgroup analyses, the odds ratio for each subgroup was approximately 3, regarding endometriosis diagnosis (see Figure 3), criteria used for irritable bowel syndrome (see Figure 4), and NOS score (see Figure 5). Visual inspection of the funnel plot appears asymmetrical, suggesting the presence of publication bias (see Figure 7).

Endometriosis diagnosis

There were 9 studies (28,888 patients) in the meta-analysis that confirmed endometriosis surgically, and 2 studies (67,161 patients) that used the ICD-9-CM 617.x codes to diagnosis endometriosis. The random effects model showed a significant association between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome with a pooled odds ratio of 3.0 (95% CI = 2.18, 4.11) (see Figure 3).

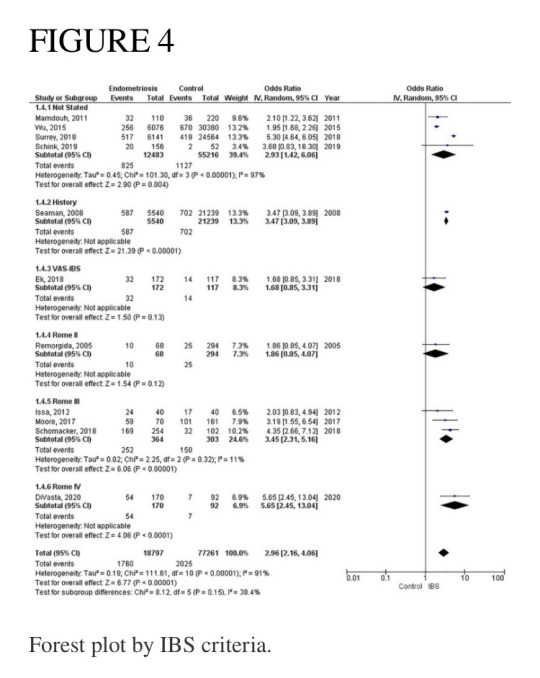

Irritable bowel syndrome diagnostic criteria

Four studies (67,699 patients) did not state what criteria were used to diagnose irritable bowel syndrome, three studies (667 patients) used the Rome III criteria, and one study each used the following as their criteria: history (26,779 patients); VAS-IBS (289 patients); Rome II (362 patients), and Rome IV (323 patients). The random effects model shows a significant association between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome, with a combined odds ratio of 2.96 (95% CI = 2.16, 4.06) (see Figure 4).

Pooled prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome

There were six studies (6, 19, 28–31) that estimated the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in people with endometriosis. These studies ranged in sample size from 101 to 5,540. The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in patients with endometriosis ranged from 10.6 to 52%, with a pooled estimate of 23.4% (95% CI = 9.7%, 37.2%) (see Figure 6).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis was designed to estimate the association of endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome. Our literature search included all available original studies investigating irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis, thereby allowing us to include a large number of subjects (17 studies; n = 96,974).

The most significant finding of our study is that the pooled analysis showed endometriosis was associated with an almost three-fold increase in risk of irritable bowel syndrome, and that more than 1 in 5 people with endometriosis have irritable bowel syndrome. Of particular significance, all 11 studies in the main meta-analysis showed a positive association of irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis. Moreover, almost all subjects in this analysis were followed longitudinally, either retrospectively or prospectively, thus allowing for inference on temporality vis-à-vis risk factor and disease. In addition, five studies (n = 68,129) included in this meta-analysis showed a positive association of endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome, even after adjustments were made for potential confounding variables (3, 10, 21, 25, 26). Furthermore, there were significant findings in our subgroup analyses based on diagnostic method for endometriosis, diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome, and NOS scores. More importantly, after the studies in the main meta-analysis were categorized based on the following criteria: longitudinal study design; surgical confirmation of endometriosis; Rome diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome; and NOS scores > 6, the pooled odds ratio was 2.77 (95% CI = 1.37, 5.60). Thus, this provides strong epidemiological evidence for the increased association of endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome.

Endometriosis is characterized as a chronic, estrogen-dependent inflammatory disorder with the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity (3). Affected areas encompass the pelvic peritoneum, ovaries, rectovaginal septum, the abdominal cavity, and the gastrointestinal tract.

Histologically, endometriosis can be characterized into superficial endometriosis, ovarian endometrioma (OE) and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). DIE can present with severe symptoms as the lesions penetrate deeper into the peritoneum and thus produce more pain as compared to the superficial. DIE also tends to involve the uterine ligaments, pouch of Douglas, rectum, or vagina. OE on the other hand, is the most common type of endometriosis and located in the pelvic areas or along the intestines. Multifocality of such a variably distributed lesion thus, predisposes to a variable clinical presentation the patients.

The relationship between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome has not yet been fully elucidated, and multiple theories have been proposed. One such theory is the immunological linkage through increased mast cell activation seen in both conditions (32). The major hallmarks postulated in this immunological linkage are the abnormal levels of inflammatory cytokines and immune cell activation in the peritoneal cavity (33). Retrograde menstruation has been a plausible explanation, which causes the dissemination of menstrual blood containing endometrial cells into the pelvic cavity, thus triggering symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (34). Specifically, in endometriosis, the activated mast cells have been activated near nerve endings within the pelvic and abdominal regions, and in irritable bowel syndrome they have been shown to be activated near the bowel mucosa (35). Moreover, Remorgida et al. (22) have found that the severity of gastrointestinal symptoms was directly related to the extent of infiltration of endometriotic foci in the bowel, and reversal of symptoms occurred after removal of those lesions. However, they did not find any conclusive evidence regarding endometriosis and predisposition to a specific subtype of irritable bowel syndrome.

Another theory for the increased association between these two disorders is through a hormonal linkage. This hormonal connection involves the presence of gonadotropin releasing hormone-containing neurons (36) and receptors for luteinizing hormone within the pelvic organs (37) and the enteric nervous system (38). It is hypothesized that the pain experienced in some people with irritable bowel syndrome could be as a result of the sex hormones found in afab people, as reports have shown a fluctuating exacerbation of symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome during menstruation (39). Likewise, it was observed that patients with endometriosis had worsening of gastrointestinal symptoms during the time of menstruation (30). It is posited that patients with endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome both experience visceral hypersensitivity, which is likely to contribute to the severity of gastrointestinal symptoms (24). A large population-based study reported that the highest prevalence rate for endometriosis was for the 40–44-year age group (40), and Oka et al. reported that afab people between the ages of 30–39 years were more likely to have irritable bowel syndrome when compared to those less than 30 years old (8). Thus, the prevalence for both conditions peak at approximately the same age range, just around the beginning of the menopausal period. Moreover, postmenopausal patients with irritable bowel syndrome experience symptoms more severely than premenopausal patients with irritable bowel syndrome, most likely due to modulation in the brain-gut axis as a result of hormonal changes (41). Our study was not analyzed according the age of the patient.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis on the sex differences of irritable bowel syndrome reveals that afab people are more likely to experience abdominal pain when compared to amab people, and this may be because of sex hormonal differences (42).

Other important factors to consider when examining the relationship between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome are race/ethnicity and geographical region. In their study, Bougie et al. showed that Black people were less likely than White people to have endometriosis, and that Asian people were more likely than White people to have endometriosis (43). Similarly, Wigington et al. reported that Black people were less likely than White people to have irritable bowel syndrome (44). Thus, White people were more likely to have both endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome when compared to Black people. Interestingly, of the 11 studies in our meta-analysis, only two studies stated the race of the participants (10, 27), and of these, the study by Schink investigated only Caucasian people (27).

As discussed previously, endometriosis is a chronic and multifactorial (genes, hormones, immune and environmental) and multi risk factor (family history, long menstrual cycle, low parity, and poor physical activity) associated disease (45, 46). An association between endometriosis and heavy metal sensitivity has been discussed in research that can potentially play a role in producing produce an IBS-like syndrome. Specifically, heavy metal nickel has been shown to interfere with estrogen and its receptors and thus plays a role in the pathogenesis of IBS. Researchers have even demonstrated a higher nickel level in endometriosis tissue (46, 47).

Recent global studies showed that the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome varies from country to country, ranging from 0.2% in India to 29.2% in Croatia, using the Rome III criteria, and ranging from 0.4% in India and Ghana to 21.3% in United States, using the Rome IV criteria (8). Similarly, the global prevalence rates for endometriosis in the general population ranged from 0.7 to 8.6% (4). This highlights the importance of recognizing that irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis can burden people of any race and from any country of origin, even though they can vary widely regarding presentation and response to treatment (43). Studies investigating endometriosis or irritable bowel syndrome individually were sparse for the geographical regions of South America, Central America, Africa, and Asia (8). However, the studies conducted in the United States reported the highest prevalence rate of endometriosis (48), and the highest prevalence rate of irritable bowel syndrome when using the Rome IV diagnostic criteria (11). Moreover, the studies conducted in the United States showed that people with endometriosis had the highest odds (5.65, 5.30) of having irritable bowel syndrome (see Figure 2). Thus, this points to further evidence that endometriosis is a significant contributory factor leading to irritable bowel syndrome. Needless to say, more investigation is needed regarding race/ethnicity and the association between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome.

Studies included in our meta-analysis used the Rome II, Rome III, and Rome IV criteria. The odds of irritable bowel syndrome in endometriosis increased with each subsequent updated version of the Rome criteria (odds ratio from 1.86 to 3.45 to 5.65), respectively. However, when interpreting these differences, one should also consider the significant heterogeneity that exists regarding study design and sample size. Moreover, recent studies have shown that the diagnostic outcomes for Rome II and Rome III criteria differ significantly (49), whereas there were comparable findings for Rome III and Rome IV criteria (50). Nevertheless, there is a markedly increased risk associated with endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome, regardless of the criteria used to diagnose irritable bowel syndrome. The basis of the Rome criteria relies on its definition of irritable bowel syndrome in which recurrent abdominal pain is associated with defecation or a change in bowel habits (17). Thus, the Rome criteria classifies patients as different subtypes based on bowel habits: irritable bowel syndrome with predominant constipation (IBS-C), irritable bowel syndrome with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D), irritable bowel syndrome with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M) or irritable bowel syndrome, unclassified (IBS-U) (17). However, our data does not include information on these subtypes. Therefore, we cannot conclusively state whether endometriosis increases the risk of a specific subtype of irritable bowel syndrome over another, or if it increases the risk of all subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome.

Our meta-analysis included one study that used the visual analog scale for irritable bowel syndrome (VAS-IBS) to diagnose patients with irritable bowel syndrome. The VAS-IBS is a patient-centered questionnaire comprised of six categories: Abdominal Pain, Diarrhea, Constipation, Bloating and Flatulence, Abnormal bowel passage, and Vomiting and Nausea (20). The items in the VAS-IBS capture the main physical concerns people with irritable bowel syndrome might experience. All symptoms, except vomiting and nausea, support the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Even though the majority of studies in our meta-analysis used the Rome criteria to establish a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome, the VAS-IBS was shown to be an accurate and reliable questionnaire to diagnose irritable bowel syndrome (20).

Our literature search found two meta-analyses on endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome (51, 52). Even though they had similar findings to ours regarding the increased association of endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome, we believe that our review provides a more detailed analysis on various factors such as endometriosis diagnosis and irritable bowel syndrome diagnosis, and the pooled prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in patients with endometriosis.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this meta-analysis include incorporation of all available studies, with subsequent sub-analyses. Both observational and interventional studies were included. In addition, most studies included in the meta-analysis have a quality assessment rating greater than 6. Moreover, by independently reviewing articles and selecting those that fit our criteria, we concluded with a large-scale study from various geographic regions of the world that include North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Oceana. This allowed us to interpret the risk of irritable bowel syndrome in people with endometriosis from an extensive and multiethnic perspective. In addition, this is the first meta-analysis to include a pooled estimate of the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in people with endometriosis.

Our study has a number of potential limitations. While select studies employed either the Rome II, Rome III, Rome IV, or the visual analog scale for irritable bowel syndrome (VAS-IBS) as their criteria to gather symptomatic data on irritable bowel syndrome, the majority of studies in this meta-analysis did not state what criteria were used to diagnose irritable bowel syndrome. The anatomical location of endometriosis and the IBS subtypes was not described as relevant description was not available in the included studies. Nonetheless, after subgroup analysis by whether criteria was used or not, pooled estimates revealed similar results in these groups. These estimates were also reflected in the overall combined odds ratio for all studies. Thus, omitting the criteria used for establishing irritable bowel syndrome did not pose any significant error in this analysis. Another limitation of this study is that data from the two largest retrospective cohort studies identified patients with endometriosis using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) 617.x codes, whereas all other studies stated that laparoscopy/laparotomy/clinical inspection was used as the mode of diagnosis. There is a significant variation in clinical diagnosis of endometriosis due to the costs and invasive diagnostic techniques including laparoscopic or surgical diagnosis. This has led to more reliance on radiological diagnosis for the same. Nevertheless, the surgical diagnostic methods are still considered the gold standard. Additionally, IBS diagnostic criteria are not based on standard guidelines or criteria. Most commonly used are the Manning and the Rome criteria which are possibly too general and vague for a specific diagnosis. Thus, an inevitable overlap occurs in the diagnosis of endometriosis and IBS (53).

Therefore, there was some inconsistency regarding identification of endometriosis. Nevertheless, our subgroup analysis regarding endometriosis diagnosis showed similar pooled estimates. However, despite these limitations, the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome remains a challenge with the fluctuation in symptoms and its symptoms mimicking other disorders like endometriosis (17).

Recommendations

Our database search revealed that no studies were conducted in Central America or South America, and only a solitary study each arose out of Africa and Asia. Thus, we recommend that studies be conducted in these regions of the world to give globally representative estimates of the risk associated with these conditions. Furthermore, since the majority of participants were investigated in retrospective cohort studies, we recommend that researchers conduct large-scale prospective cohort studies to investigate the risk of irritable bowel syndrome (preferably using the Rome IV criteria) in people with endometriosis (with diagnosis confirmed surgically). Moreover, we suggest that studies be conducted to investigate whether endometriosis predisposes to any specific subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome.

Conclusion

This review provides significant epidemiological evidence for the association between endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome. People with endometriosis are three times more likely to have irritable bowel syndrome compared to people without endometriosis. Doctors should be mindful that patients with endometriosis can also have irritable bowel syndrome.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MN, MR, and SL contributed to the conception and design of the study. ME organized the database. PR and SN performed the statistical analysis. AV wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MN, MR, AV, and ME wrote the sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

#frontiers in medicine#pubmed central#endometriosis#gender neutral language#trans healthcare#afab health#endowarrior#ibs#irritable bowel disease#irritable bowel syndrome#scientific study#scientific news#comorbid conditions

1 note

·

View note

Text

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Endometriosis

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

Medically Reviewed by Traci C. Johnson, MD on December 12, 2022

Endometriosis happens when tissue that is similar to the tissue that grows inside a person’s uterus, grows outside of the uterus.

The tissue acts like regular uterine tissue does during your period: it will break apart and bleed at the end of the cycle. But this blood has nowhere to go. Surrounding areas may become inflamed or swollen. You may have scar tissue and lesions.

Endometriosis is most common on your ovaries.

Types of Endometriosis

There are three main types of endometriosis, based on where it is:

Superficial peritoneal lesion. This is the most common kind. You have lesions on your peritoneum, a thin film that lines your pelvic cavity.

Endometrioma (ovarian lesion). These dark, fluid-filled cysts, also called chocolate cysts, form deep in your ovaries. They don’t respond well to treatment and can damage healthy tissue.

Deeply infiltrating endometriosis. This type grows under your peritoneum and can involve organs near your uterus, such as your bowels or bladder. About 1% to 5% of people with endometriosis have it.

Endometriosis Symptoms

You might not notice any symptoms. When you have them, they can include:

Back pain during your period

Severe menstrual cramps

Pain when pooping or peeing, especially during your period

Unusual or heavy bleeding during periods

Blood in your stool or urine

Diarrhea or constipation

Painful sex

Fatigue that won’t go away

Trouble getting pregnant

Endometriosis Causes

Doctors don’t know exactly what causes endometriosis. Some experts think menstrual blood that contains endometrial cells may pass back through your fallopian tubes and into your pelvic cavity, where the cells stick to your organs. This is called retrograde menstruation.

Your genes could also play a role. If your parent or sibling has endometriosis, you’re more likely to get it. Research shows that it tends to get worse from one generation to the next.

Some people with endometriosis also have immune system disorders. But doctors aren’t sure whether there’s a link.

Endometriosis Complications

Severe endometriosis pain can affect your quality of life. Some people struggle with anxiety or depression. Medical treatments and mental health care can help.

Endometriosis may raise your risk of ovarian cancer or another cancer called endometriosis-associated adenocarcinoma.

Endometriosis and Fertility

Endometriosis is the leading cause of infertility. It affects about 5 million people in the United States, many in their 30s and 40s. Nearly 2 of every 5 AFAB people who can’t get pregnant have it.

If endometriosis interferes with your reproductive organs, your ability to get pregnant can become an issue:

When endometrial tissue wraps around your ovaries, it can block your eggs from releasing

The tissue can block sperm from making its way up your fallopian tubes.

It can stop a fertilized egg from sliding down your tubes to your uterus.

A surgeon can fix those problems, but endometriosis can make it hard for you to conceive in other ways:

It can change your body’s hormonal chemistry.

It can cause your body’s immune system to attack the embryo.

It can affect the layer of tissue lining your uterus where the egg implants itself.

Your doctor can surgically remove the endometrial tissue. This clears the way for the sperm to fertilize the egg.

If surgery isn’t an option, you might consider intrauterine insemination (IUI), which involves putting sperm directly into your uterus.

Your doctor may suggest pairing IUI with “controlled ovarian hyperstimulation,” which means using medicine to help your ovaries put out more eggs. People who use this technique are more likely to conceive than those who don’t get help.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) is another option. It can raise your chances of conceiving, but the statistics on IVF pregnancies vary.

Endometriosis Diagnosis

Your doctor might suspect endometriosis based on your symptoms. To confirm it, they can do tests including:

Pelvic exam. Your doctor might be able to feel cysts or scars behind your uterus.

Imaging tests. An ultrasound, a CT scan, or an MRI can make detailed pictures of your organs.

Laparoscopy. Your doctor makes a small cut in your belly and inserts a thin tube with a camera on the end (called a laparoscope). They can see where and how big the lesions are. This is usually the only way to be totally certain that you have endometriosis.

Biopsy. Your doctor takes a sample of tissue, often during a laparoscopy, and a specialist looks at it under a microscope to confirm the diagnosis.

Endometriosis Stages

Doctors use the American Society of Reproductive Medicine’s four stages of endometriosis:

Stage I (minimal). You have a few small lesions but no scar tissue.

Stage II (mild). There are more lesions but no scar tissue. Less than 2 inches of your abdomen are involved.

Stage III (moderate). The lesions may be deep. You may have endometriomas and scar tissue around your ovaries or fallopian tubes.

Stage IV (severe). There are many lesions and maybe large cysts in your ovaries. You may have scar tissue around your ovaries and fallopian tubes or between your uterus and the lower parts of your intestines.

The stages don’t take pain or symptoms into account. For example, stage I endometriosis can cause severe pain, but a person who has stage IV could have no symptoms at all.

Questions For Your Doctor

If you’ve been diagnosed with endometriosis, you might want to ask things like:

Why is endometriosis painful?

What can I do to control my endometriosis symptoms?

Do I need medication? How does it work?

What are the side effects of medication for endometriosis?

Will endometriosis affect my sex life?

How do birth control pills affect endometriosis?

If I’m having trouble getting pregnant, could fertility treatments help? What about surgery?

Can surgery stop my symptoms?

What might happen if I do nothing? Can endometriosis go away without drugs or surgery?

Will it last my whole life?

Should I consider joining a clinical trial?

How often do I need to see a doctor?

Endometriosis Treatments

There’s no cure for endometriosis. Treatments usually include surgery or medication. You might need to try different treatments to find what helps you feel better.

Pain medicine. Your doctor may recommend an over-the-counter pain reliever. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) or naproxen (Aleve) work for many people. If these don’t relieve your pain, ask about other options.

Hormones. Hormone therapy lowers the amount of estrogen your body creates and can stop your period. This helps lesions bleed less so you don’t have as much inflammation, scarring, and cyst formation. Common hormones include:

Birth control pills, patches, and vaginal rings

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH) agonists and antagonists such as elagolix sodium (Orilissa) or leuprolide (Lupron)

Progestin-only contraceptives

Danazol (danocrine)

Surgery. Your doctor might recommend surgery to take out as much of the affected tissue as possible. In some cases, surgery helps symptoms and can make you more likely to get pregnant. Your doctor might use a laparoscope or do a standard surgery that uses larger cuts. Pain sometimes comes back after surgery.

In the most severe cases, you may need a surgery called a hysterectomy to take out your ovaries, uterus, and cervix. Without them, you can’t get pregnant later.

Lifestyle Changes for Endometriosis

Warm baths, hot water bottles, and heating pads can give quick relief from endometriosis pain. Over time, lifestyle changes like these might also help:

Eat right. Research has shown a link between endometriosis and diets that are low in fruits and vegetables and high in red meat. Some experts think the high amount of fat in meat like beef encourages your body to produce chemicals called prostaglandins, which may lead to more estrogen production. This extra estrogen could be what causes excess endometrial tissue to grow.

Add more fresh fruits and vegetables by making them the heart of your meals. Stocking your refrigerator with pre-washed and cut fruit and vegetables can help you eat more of both.

Research has also found foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, like salmon and walnuts, to be helpful. One study showed that people who ate the highest amount of omega-3 fatty acids were 33% less likely to develop endometriosis than the people who ate the least amount.

By comparison, people who ate the most trans fats had a 48% higher risk than those who ate the least, so the type of fat you eat matters.

Also, avoid alcohol and caffeine. Drinking caffeinated coffee and soda seems to increase your chances of developing endometriosis, although researchers aren’t sure why. Alcohol is also associated with a higher risk.

Exercise regularly. There are a lot of reasons exercise is a great way to manage your endometriosis. Working out encourages your heart to pump blood to all your organs, improve circulation, and help nutrients and oxygen flow to all your systems.

AFAB people who exercise may have less estrogen and lighter periods, which can help improve their symptoms of endometriosis over time. But there’s even more: studies have shown that the more time you devote to high-intensity exercises like running or biking, the less likely you are to ever get endometriosis.

Exercise helps reduce stress. And because it releases brain chemicals called endorphins, it can actually relieve pain. Even just a few minutes of a physical activity that makes you breathe hard or sweat can create that effect.

Lower-intensity workouts like yoga can be beneficial, too, by stretching the tissues and muscles in your pelvis for pain relief and stress reduction.

Manage stress. Researchers think stress can make endometriosis worse. In fact, the condition itself might be the cause of your stress because of the severe pain and other side effects.

Finding ways to manage stress—whether it’s through yoga or meditation, or simply by carving out time for self-care—can help you ease symptoms. It may also be helpful to see a therapist who can offer tips for dealing with stress.

Look at alternative therapies. Although there isn’t enough research that supports the use of alternative natural therapies for endometriosis, some people find relief from their symptoms through these techniques, including:

Acupuncture

Herbal medicine

Ayurveda

Massage

If you’re interested in trying an alternative therapy, be sure to talk to your doctor first, especially if you’re considering taking over-the-counter supplements. They could have side effects that you don’t know about. And never exceed the recommended dosage or take more than one supplement at a time.

0 notes

Text

In ‘historic’ move, Spain approves Europe’s first law on menstrual leave

Updated on Feb 17, 2023 04:10 AM IST

Menstrual leave is currently offered in only a small number of countries across the globe, among them Japan, Indonesia and Zambia.

Spanish lawmakers on Thursday gave final approval to a law granting paid medical leave to people suffering severe period pain, becoming the first European country to advance such legislation.

The law, which passed by 184 votes in a favour to 154 against, is aimed at breaking a taboo on the subject, the government has said.

Menstrual leave is currently offered in only a small number of countries across the globe, among them Japan, Indonesia and Zambia.

“It is a historic day for feminist progress,” Equality Minister Irene Momtero tweeted ahead of the vote.

The legislation entitles workers experiencing period pain to as much time off as they need, with the state social security system — not employers — picking up the tab for the sick leave.

As with paid leave for other health reasons, a doctor must approve the temporary medical incapacity.

The length of sick leave that doctors will be able to grant people suffering from painful periods has not been specified in law.

About a third of people who menstruate suffer from severe pain, according to the Spanish Gynecology and Obstetrics Society.

The measure has created divisions among both politicians and unions, with the UGT, one of Spain’s largest trade unions, warning it could stigmatise menstruating people in the workplace and favour the recruitment of amab people.

The main opposition conservative Popular Party (PP) also warned the law risks “stigmatising” menstruating people and could have “negative consequences in the labour market” for them.

“Menstrual leave” is one of the key measures in the broader legislation, which also provides for increased access to abortion in public hospitals.

Less than 15 percent of abortions performed in the country take place in such institutions, mainly because of conscientious objections by doctors.

The new law also allows minors to have abortions without parental permission at 16 and 17 years of age, reversing a requirement introduced by a previous conservative government in 2015.

Spain, a European leader in AFAB health rights, decriminalised abortion in 1985, and in 2010, it passed a law that allows pregnant people to opt freely for abortion during the first 14 weeks of pregnancy in most cases.

#hindustan times#menstrual leave#menstruation#gender neutral language#afab health#spain#trans healthcare

0 notes

Text

What is genderneutralendo?

Endometriosis (AKA endo) is a common health condition affecting the AFAB reproductive system where tissues resembling uterine lining grow outside the uterus. Some of its most recognizable symptoms are infertility and extremely painful period cramps.

Image ©Marochkina Anastasiia / Shutterstock.com

@genderneutralendo is run by me, AJ (they/them). I have endometriosis among other chronic health issues, but trying to learn about my endo is incredibly difficult since most resources are so heavily gendered.

I believe equal access to medical information is a basic right. Having to push through unnecessary gender dysphoria to learn about your own health is not equal access. So I decided to “translate” some of these resources into gender neutral, trans+ inclusive language.

I’m not a medical professional, and in fact have never taken an anatomy class. I alter each article as little as possible, so trust the information here as much as you would the credited source. While I use my best judgement, my only goal is to make information about endometriosis accessible, not to fact check it.

1 note

·

View note