Photo

Uruk

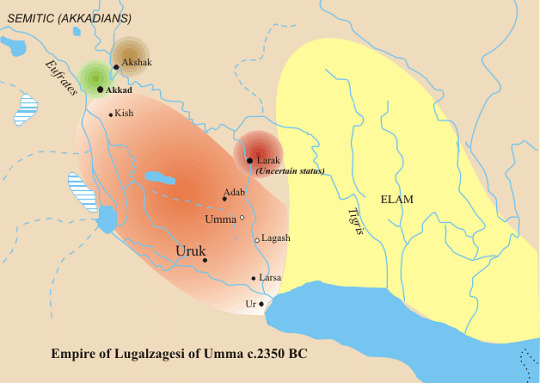

Uruk was one of the most important cities (at one time, the most important) in ancient Mesopotamia. According to the Sumerian King List, it was founded by King Enmerkar c. 4500 BCE. Uruk is best known as the birthplace of writing c. 3200 BCE as well as for its architecture and other cultural innovations.

Located in the southern region of Sumer (modern day Warka, Iraq), Uruk was known in the Aramaic language as Erech which, it is believed, gave rise to the modern name for the country of Iraq, though another likely derivation is Al-Iraq, the Arabic name for the region of Babylonia. The city of Uruk is most famous for its great king Gilgamesh and the epic tale of his quest for immortality but also for a number of firsts in the development of civilization which occurred there.

It is considered the first true city in the world, the origin of writing, the first example of architectural work in stone and the building of great stone structures, the origin of the ziggurat, and the first city to develop the cylinder seal which the ancient Mesopotamians used to designate personal property or as a signature on documents. Considering the importance the cylinder seal had for the people of the time, and that it stood for one’s personal identity and reputation, Uruk could also be credited as the city which first recognized the importance of the individual in the collective community.

The city was continuously inhabited from its founding until c. 300 CE when, owing to both natural and man-made influences, people began to desert the area. By this time, it had depleted natural resources in the surrounding area and was no longer a major political or commercial power. It lay abandoned and buried until excavated in 1853 by William Loftus for the British Museum.

The Uruk Period

The Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BCE) when the so-called Ubaid people first inhabited the region of Sumer is followed by the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) during which time cities began to develop across Mesopotamia and Uruk became the most influential. The Uruk Period is divided into 8 phases from the oldest, through its prominence, and into its decline based upon the levels of the ruins excavated and the history which the artifacts found there reveal. The city was most influential between 4100-c.3000 BCE when Uruk was the largest urban center and the hub of trade and administration.

In precisely what manner Uruk ruled the region, why and how it became the first city in the world, and in what manner it exercised its authority is not fully known. Scholar Gwendolyn Leick writes:

The Uruk phenomenon is still much debated, as to what extent Uruk exercised political control over the large area covered by the Uruk artifacts, whether this relied on the use of force, and which institutions were in charge. Too little of the site has been excavated to provide any firm answers to these questions. However, it is clear that, at this time, the urbanization process was set in motion, concentrated at Uruk itself. (183-184)

Since the city of Ur had a more advantageous placement for trade, further south toward the Persian Gulf, it would seem to make sense that city, rather than Uruk, would have wielded more influence but this is not the case.

Artifacts from Uruk appear at virtually every excavated site throughout Mesopotamia and even in Egypt. The historian Julian Reade notes:

Perhaps the most striking example of the wide spread of some features of the Uruk culture consists in the distribution of what must be one of the crudest forms ever made, the so-called beveled-rim bowl. This kind of bowl, mould-made and mass-produced, is found in large numbers throughout Mesopotamia and beyond. (30)

This bowl was the means by which workers seem to have been paid: by a certain amount of grain ladled into a standard-sized bowl. The remains of these bowls, throughout all of Mesopotamia, suggest that they “were frequently discarded immediately after use, like the aluminum foil containing a modern take-away meal” (Reade, 30). So popular was the beveled-rim bowl that manufacturing centres sprang up throughout Mesopotamia extending as far away from Uruk as the city of Mari in the far north. Because of this, it is unclear if the bowl originated at Uruk or elsewhere (though Uruk is generally held as the bowl’s origin). If at Uruk, then the beveled-rim bowl must be counted among the many of the city’s accomplishments as it is the first known example of a mass-produced product.

Continue reading…

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome: A History of the Ptolemies

Guy de la Bédoyère’s The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome deals with the decline of the Ptolemaic dynasty, which ruled Egypt from 323 to 30 BCE. The book explores how Egypt was weakened by civil wars and rebellion until it became an easy target for the rising Roman Republic. It is comprehensive but still accessible to general audiences.

The book is divided into three parts, each comprising several chapters. Part One deals with the Ptolemaic dynasty’s foundation and the beginnings of its decline under Ptolemy IV. Part Two includes four chapters on what life was like in Ptolemaic Egypt. It covers topics like the people of Egypt, religious beliefs, mummification and funerary practices, crime, and governance. Part Three concludes the book with an eight-chapter overview of the later Ptolemies and their relationship with Rome. The last two chapters focus on Egypt’s final ruler Cleopatra VII, who committed suicide after being defeated by the Roman leader Octavian.

The book explains the Roman annexation of Ptolemaic Egypt in the broader context of Mediterranean politics at the end of the 1st millennium BCE. It focuses on the outbreaks of civil war and rebellion in the late 3rd century BCE, as Egypt was destabilized by economic shocks and the loss of overseas territories. Meanwhile, the Roman Republic emerged as the dominant power in the western Mediterranean and began extending its influence eastward.

As Rome ascended, the Ptolemaic dynasty grew to rely on it for political and military support, which paved the way for Egypt’s fall. This core idea of Ptolemaic decline and increasing reliance on Rome is widely accepted in academia, and de la Bédoyère compellingly presents it to new readers. He portrays the complex personalities of key figures who shaped Egypt’s destiny. The ruthless choices made by the last Ptolemies as they fought for the survival of their dynasty are portrayed sympathetically but never apologetically. The Romans are similarly complex, each having gotten involved in Egypt for their own reasons.

Guy de la Bédoyère is a historian and archaeologist who has written many books about Rome and Egypt aimed at general audiences. He utilizes a wide collection of archaeological and textual evidence to support his arguments. He also includes anecdotes from first-hand accounts of life in Ptolemaic Egypt, providing readers with a personal insight into the past.

At the end of the book, there is a very useful collection of appendices. These include a simple timeline, family trees of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid dynasties, an explanation of the royal titulary used by Ptolemaic queens, and an overview of Ptolemaic coinage. It has extensive notes and recommendations for further reading, which make it a good starting point for readers interested in learning more about Ptolemaic Egypt.

The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome compares favorably to the available English-language monographs on Ptolemaic Egypt. It is written in a light tone and is not overly technical, but it does address topics like economic and political systems at length. While accessible to casual audiences, it is most well-suited to readers who have some familiarity with Classical antiquity. Students and serious enthusiasts interested in Ptolemaic history will particularly enjoy this.

Continue reading…

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hate -

This is the story of a society that is falling. As she falls, she keeps saying, to calm herself down: It's been going quite well up to this point, it's been going quite well up to this point, it's been going quite well up to this point. But it's not the fall that's important, it's the landing!

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Ain't nobody dope as me, I'm just so fresh, so clean So fresh and so clean, clean Don't you think I'm so sexy? I'm just so fresh, so clean So fresh and so clean, clean Ain't nobody dope as me, I'm just so fresh, so clean So fresh and so clean, clean I love when you stare at me, I'm just so fresh, so clean So fresh and so clean, clean

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Yeah, yeah, yeah (Woo), rrahOld school players to new school fools'Kast keep it jumping like kangaroosWe'll skew it on the bar-b, we ain't tryin to lose

0 notes

Text

youtube

E-A-Ski - Can't Get Enough feat. San Quinn & Allen Anthony

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Blade (1998): Blade's Entrance/the First Fight Scene

1 note

·

View note

Text

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANCIENT SUMERIAN COFFEE CAKE

This is a loaf of bread made in the first century AD, discovered at Pompeii, preserved for centuries in the volcanic ashes of Mount Vesuvius. So it's probably a little dry. The markings visible on the top are from a Roman bread stamp, which bakeries were required to use in order to mark the source of the loaves and prevent fraud. Nobody likes fake bread.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Spanish Main

The Spanish Main refers, in its widest sense, to the Spanish Empire in the Americas from Florida in the north to the northern coast of Brazil in the south, including the Caribbean. The term was initially more limited and referred only to the mainland Spanish territories in northern South America. It was a name particularly popular with writers of pirate fiction as a handy and romantic term to cover the field of operation of privateers, buccaneers, and pirates from the 16th to 18th centuries.

Continue reading…

35 notes

·

View notes