SF, Anime, Mecha, and Toku fan. Provisional Tumblr account, will mostly repost own Blogspot links and transplanting text.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Updated for 2025 with Seed Freedom, Gquuuuuux info.

How to Get Into Gundam (March 2025 Version)

(Originally published on Blogspot on February 20th, 2023. Updated March 23, 2025)

Gundam is a vast franchise that can seem insurmountable at a first glance, so how do you begin approaching it?

The answer I would normally give for getting into any series is “watch by its production order,” but I feel that’s not necessarily the best for Gundam considering how varied and huge it is, and there's still a lot of shows I haven't seen. This is not a recommendation on quality or show style. Instead, I want to more directly explain how these shows relate.

The Three Rules

Here’s three of the main things to keep in mind when approaching a show.

Anything in the “Universal Century” (UC) takes place in a larger shared timeline and setting.

Anything that doesn’t is an “Alternate Universe” (AU) that is totally standalone, unless one of those standalone shows had a sequel.

Most UC stuff that isn’t a full TV show is usually self-contained.

Gundam seems complicated because there’s so many shows, movies, OVAs, and other formats that it can feel overwhelming, but it’s rather straightforward if you know these rules going in. It’s very easy to hop around to different entries because most of them aren’t connected at all. Almost every show has its own slate of characters and a different setting, even those in the UC timeline.

Every show features robots and mecha of some kind, and most of them have the name “Gundam” in the title and for one or some of its robots. The main thing all the entries share are some general themes and iconography, but they each have their own aesthetic spins on mecha and character design.

Most entries center around wars and conflicts with a somewhat serious tone, but this can also vary depending on the show. The uniting element of all the entries is more so the “Gundam” branding than anything else even if there are similarities, homages, or reinterpretations between them.

Examples

Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) is the first entry in the UC timeline and takes place during a conflict called the “One Year War”. It has a sequel show called Zeta Gundam (1985) that takes place a few years later and has some returning characters. The show Victory Gundam (1993) is also in the UC timeline, but it takes place much later and has no characters from either of those shows that it can be watched without having seen the others. The OVA The 08th MS Team (1996) takes place during the UC’s “One Year War” but has an entirely different location and cast of characters than Mobile Suit Gundam, working as a side story of a much larger conflict. Most UC entries are standalone, especially so if it’s an OVA.

The AU shows are almost all independent of each other. The AU show G Gundam (1994) takes place in its own “Future Century” timeline and is centered around a battle tournament. Gundam X (1996) takes place in its own “After War” timeline with a post-apocalyptic Earth. The recent Witch from Mercury (2022) takes place in its own “Ad Stella” timeline and is centered around a tech school. None of them have anything directly in common aside from sharing the name “Gundam” in the title and for one or some of their robots.

Sometimes, an AU show is popular enough that it will get a sequel in the same universe. Gundam Wing (1995) has a sequel OVA called Gundam Wing: Endless Waltz (1998). Gundam Seed (2002) takes place in its own “Cosmic Era” timeline, but it also has a direct sequel called Gundam Seed Destiny (2004) that occurs after that series. The AU sequels have the name of their preceding entry in their title, so it’s not hard to keep track of them.

The best comparison is the Final Fantasy series. Every game in the series has its own unique world, setting, and characters, and the only shared elements are a few general designs or tropes. A few games have larger connected universes, like the large amount of spinoffs surrounding Final Fantasy VII, or Final Fantasy X having a direct sequel X-2, but almost every other entry is self-contained.

The Partial List of Entries and Timelines

Black is a series, blue is movie, green is compilation movie, red is an OVA/ONA.

Some of the OVA’s have compilation movies, but I’m mostly excluding them because they’re inessential. Almost all OVA’s are standalone. Not every OVA is included because I want to feature the primary ones.

Production dates included for perspective but featured with in-show chronological order.

Universal Century Mobile Suit Gundam: The Origin (U.C. 0068-79)—2015-18 Mobile Suit Gundam (U.C. 0079)—1979-80 Mobile Suit Gundam I—1981 Mobile Suit Gundam II: Soldiers of Sorrow—1982 Mobile Suit Gundam III: Encounters in Space—1982 Mobile Suit Gundam: Doan Cru Cruz’s Island (U.C. 0079)—2022 Mobile Suit Gundam: The 08th MS Team (U.C. 0079)—1996-99 Mobile Suit Gundam: Thunderbolt (U.C. 0079-80)—2015-17 Mobile Suit Gundam 0080: War in the Pocket (U.C 0079)—1989 Mobile Suit Gundam 0083: Stardust Memory (U.C. 0083)—1991-92 Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam (U.C 0087)—1985-86 Mobile Suit ZZ Gundam (U.C 0088)—1986-87 Mobile Suit Gundam: Char’s Counterattack (U.C.0093)—1988 Mobile Suit Gundam Unicorn (U.C. 0096)—2010-14 Mobile Suit Gundam Narrative (U.C. 0097)—2019 Mobile Suit Gundam: Hathaway’s Flash (U.C. 0105)—2021 Mobile Suit Gundam F91 (U.C. 0123) –1991 Mobile Suit Victory Gundam (U.C. 0153)—1993-94 Future Century Mobile Fighter G Gundam (F.C. 60)—1994-95 After Colony New Mobile Report Gundam Wing (A.C. 195)—1995-96 New Mobile Report Gundam Wing: Endless Waltz (A.C. 196)—1998 After War Mobile New Century Gundam X (A.W. 15)—1996-97 Correct Century Turn A Gundam (C.C. 2345)—1999-2000 Cosmic Era Mobile Suit Gundam SEED (C.E. 70)—2002-03 Mobile Suit Gundam SEED Destiny (C.E 73)—2004-05 Mobile Suit Gundam SEED C.E. 73: STARGAZER —2006 (C.E. 73) Anno Domini Mobile Suit Gundam 00 (A.D. 2307, 2311)—2007-09 Mobile Suit Gundam 00 the Movie -A Wakening of the Trailblazer (A.D. 2314)—2010 Advanced Generation Mobile Suit Gundam AGE (A.G. 115, 140-42, 164)—2011-12 Build Fighters Gundam Build Fighters (B.F.)—2013-14 Gundam Build Fighters Try (B.F)—2014-15 Gundam Build Divers (B.F.)—2018-19 Regild Century Gundam Reconguista in G (R.C. 1014)—2014-15 Five Compilation Movies—2019-22 Post Disaster Mobile Suit Gundam Iron Blooded Orphans (P.D. 315)—2015-17 Ad Stella Mobile Suit Gundam The Witch from Mercury (A.S 122) —2022-2023 Alternate Universal Century Mobile Suit Gundam GQuuuuuuX (Alt U.C. 0079, 0084) —2025 Mobile Suit Gundam GQuuuuuuX: Beginning (Alt U.C. 0079, 0084)—2025

Starting Points

For a bit more guidance, I have some thoughts on which entries work better if you’re totally blind trying to get a feel for Gundam as a whole. This list is based on accessibility relative to other entries. A few of these descriptions have value judgements, but I’m mostly avoiding them otherwise. This is also not comprehensive, but I wanted to get most of the major entries.

Good Places to Start

Mobile Suit Gundam (The original series that started it all. The three compilation movies truncate some parts but are decently paced and capture the story well)

The Origin (More recent, it’s a slight alternate take on parts of the original series for newer fans, and it’s a prequel without getting into too many references.)

08th MS Team (Self-contained side war story)

Thunderbolt (Self-contained war story)

Wing (Standalone, first one brought into the US)

X (Standalone but uses new spins on some terminology from older shows)

SEED (Standalone, but it is a then-modern take on some parts of the original series)

00 (Standalone)

AGE (Standalone)

Iron-Blooded Orphans (Standalone)

Witch from Mercury (Standalone)

Bad Places to Start

Zeta, ZZ, Char’s Counterattack (All sequels with each other and to the original series, though CCA is a bit more standalone than the others)

SEED Destiny, SEED Freedom (Sequels to SEED and each other)

Build Fighters (Kind of a meta series where kids build Gundam toys and control them in battle. Very stylistically different and geared towards people familiar with the franchise)

Narrative (Tied into Unicorn’s events)

Either/Or

War in the Pocket (Stand-alone, but is a war side story focusing on civilians that’s different from a lot of other shows)

0083 (Mostly stand alone, but has a few slight connections to 0079 and Zeta)

F91 (Somewhat truncated movie that’s mostly unconnected)

Victory (Fairly stand-alone)

G Gundam (Intentionally made to be different and is a tournament fighter, not representative of the rest of the series)

Turn A (Very different stylistically, but some parts near the end work better having seen other series)

Unicorn (Takes place later in the UC without large connections at the start, but more towards the end)

Reconguista in G / “G Reco” (Standalone, but is a more peculiar vision of the original series’ creator)

Doan Cru Cruz (Alternate take on a notorious episode of the original show. Mostly self-contained but banks on familiarity with the show’s cast)

Gquuuuux (New story after an alternate version of 0079's events, but see below)

What is Gquuuuuux?

This one is slightly trickier. The show has not finished as of this post, but it is essentially a “What If?”/alternate timeline of the original Mobile Suit Gundam 0079 that goes through to its final events as a prelude before a time skip to a new status quo for the remainder. However, the core plot so far is mostly its own thing and does not require full knowledge of 0079 to understand it as presented, but the 0079 compilation movies help clarify some of the broader context of that prelude. It’s setup more like an AU show with an alternate UC portion as the backstory. Additionally, the first three episodes were recut as a compilation debut movie with the alternate timeline portions happening all sequentially before the time skip, but the show may sparse them out as flashbacks. I think the post time-skip setup is comprehensible enough without seeing any of 0079, and even the prelude is so divergent that seeing 0079 more helps with “spot the difference” rather than anything else. It feels like you’re missing more than you technically are, but watching the 0079 movies wouldn’t hurt.

Miscellany

The common parlance in English is to call each series “Mobile Suit Gundam [Name].” For example, Mobile Suit Gundam Wing is technically “New Mobile Report Gundam Wing,” but almost no one calls it that.

Some shows have common fan abbreviations. Reconguista in G is often shortened to “G-Reco,” and The Witch from Mercury is often shortened to “G-Witch”.

The original Gundam show is commonly abbreviated as “Gundam ‘79”, “Gundam 0079”, or “First Gundam”. Almost every TV show is around 40-50 episodes, though some have “Season” splits around the halfway point.

The dubbing history of the shows is mostly spotty but gets more consistent in the 2000’s onwards, although even there the studios involved vary quite a bit.

Where Do I Watch?

I didn’t want to make this post too long, so I didn’t include the streaming options, especially since they’re very scattered and shifting between different services at the time of writing. Almost all of these have physical American Blu-Ray releases via the Crunchyroll store (formerly Rightstuf), which can be a bit pricey but are good option to at least own them. However, several of the older releases (published by Nozomi Entertainment) are going out of print at the moment but will hopefully see an eventual physical re-release.

Closing Thoughts

The baseline recommendation I’d give is to follow those three rules, and then just look at an intro description of a show that looks interesting and head from there. Chances are if you don’t like one entry, there’s another more to your tastes. Gundam encompasses a lot of entries and properties, and once you get over the initial scale of the franchise, getting into it is as simple as finding a show that looks cool.

(Edit 7/9/23: Moved G-Reco from "Bad Place to Start" to "Either/Or", updated compilation movies listing, edited some descriptions to be less opinionated) (Edit 3/23/25: Added Seed Freedom and Gquuuuuux, updated info about stores and availability)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

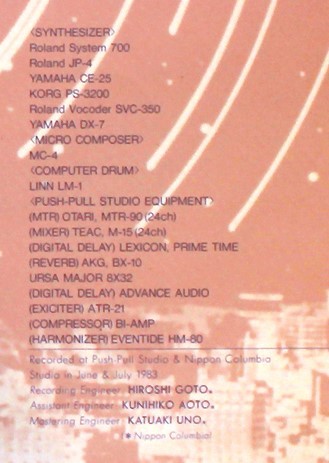

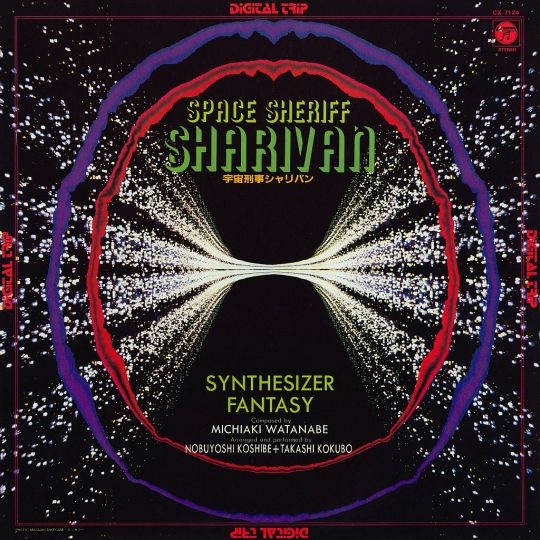

Update: The Sharivan Digital Trip is now also on streaming too, at the end of the fourth Metal Heroes Super Hero Chronicle album.

That does mean this is the album cover for the tracks, but still

Diving into the Digital Trip

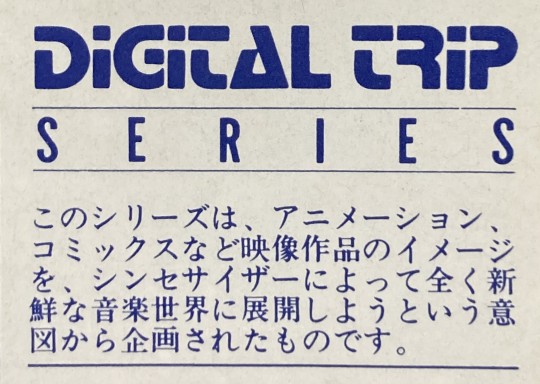

“This series was conceived with the intention of taking impressions from animation, comics, and other visual works and developing them into a completely fresh musical world using synthesizers.”

-Obi Strip Digital Trip Series Description, 1983 (SDF Macross DT, translated by Windii)

Intro

When I first started listening through tokusatsu soundtracks, I was going through the two-disc set for Uchuu Keiji Sharivan’s BGM and noticed that the second disc began with a set of songs titled “DIGITAL TRIP Uchuu Keiji Sharivan SYNTHESIZER FANTASY.” Upon playing those curious tracks, I was greeted with a very electronic, synthesized, and striking series of compositions. They were still recognizable as variations of the OST and BGM I’d heard earlier, yet they sounded almost otherworldly.

Years of anisong searching and listening later, and now as an avid music enthusiast, I’ve plunged into the huge range of the Digital Trip – Synthesizer Fantasy albums. Though only lasting around five years, the series saw many releases from a variety of arrangers offering their own, synthesizer-heavy takes on anime and other Japanese media music.

Some of the albums recently received worldwide streaming releases for the first time, but I wanted to write about this series anyways because of how much I enjoyed listening through and discovering so many favorites. I love synthesizer music of all kinds, especially ones that aim for their own distinctive style. The Digital Trip series is unique among both electronic and anime music, and I think it’s worth highlighting as a creative and entertaining series of albums.

This retrospective is a mix of contextual overview, notes on the styles of the main arrangers, a look at some of the tech used, the end of the line itself, and ten personal album recommendations.

(VGMDB is the source for most of the credits and dates in this post.)

Overview

Digital Trip – Synthesizer Fantasy is a series of instrumental image albums released by the Nippon Columbia record label in Japan from December 1981 to May 1986. 51 albums (and one compilation) were produced for it, with each receiving a simultaneous vinyl and cassette release. At its peak, multiple albums were released almost every month, though the typical schedule had more gaps.

Befitting the name, the albums are synthesizer-focused re-arrangements of vocal, BGM, and image songs for select anime, manga, and even tokusatsu. A few albums have original compositions, but the majority are reinterpretations of existing songs and scores. The albums feature some of the newest emerging synthesizers, samplers, sequencers, and drum machines of their release years, though a rare few have more traditional instruments mixed in. Despite the “digital” name, older analog synthesizers are used on some albums alongside newer digital synths.

Nippon Columbia had other similar image album lines that started running concurrently in 1983. The Jam Trip series is the same concept as the DT albums but with jazz-fusion rearrangements instead of synthy ones, and the Roman Trip series is image songs for manga and books that had not received animated adaptations yet. Some of the early DT albums are original image albums for manga, but they soon switched to covering anime while the Roman Trip line focused on new image songs for non-animated works.

Image albums were common music releases throughout the late 70s and 80s onwards, but the DT series is focused on a more specific, overarching concept of making distinctly electronic renditions. The potential of synthesizers and newer computer technologies was captivating for musicians and audiences across the world at the time, so the DT series served as a chance to both experiment with these new tools and to showcase the kind of layered and unique compositions synthesizers were capable of.

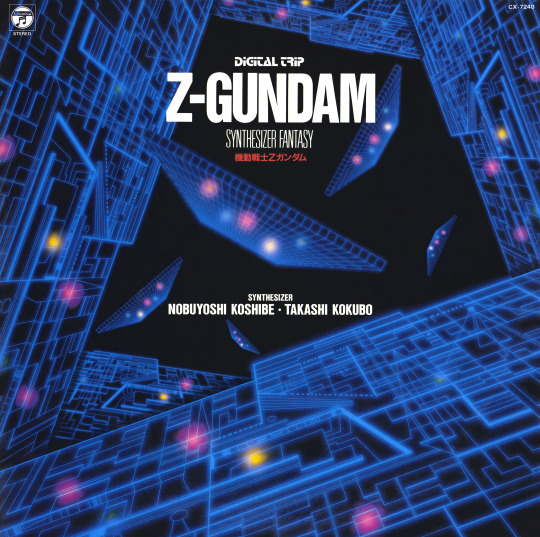

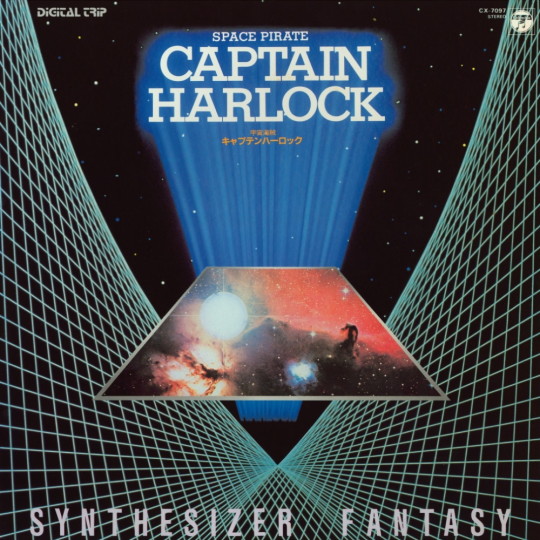

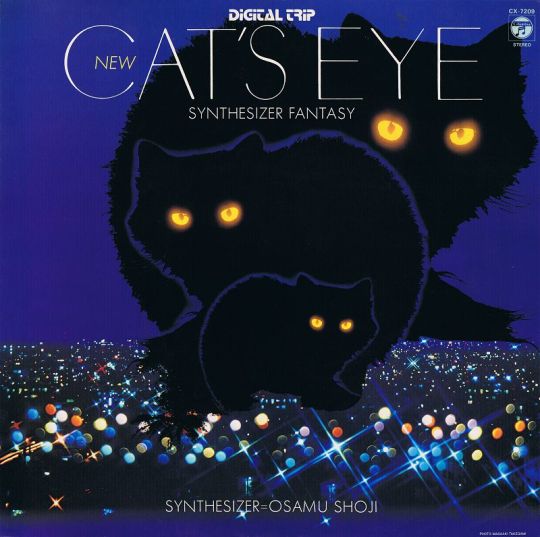

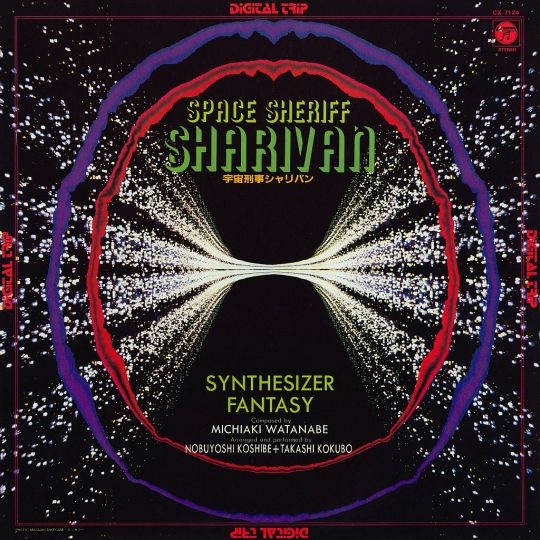

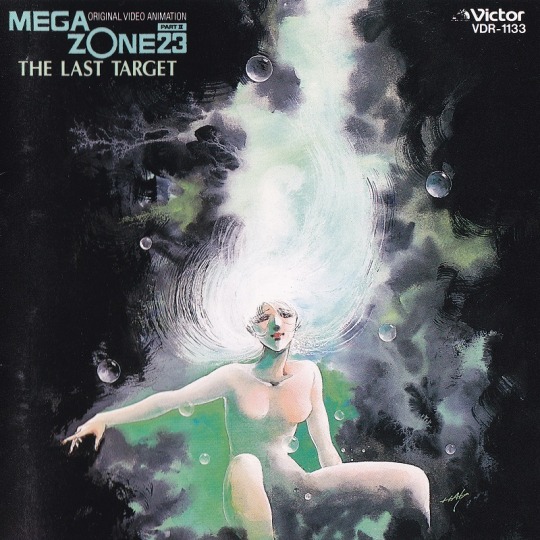

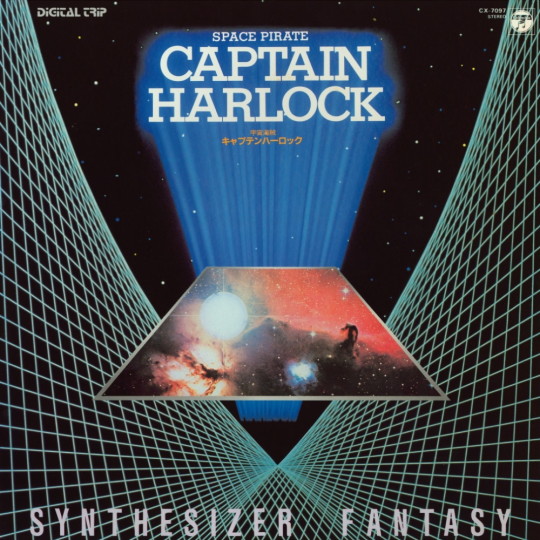

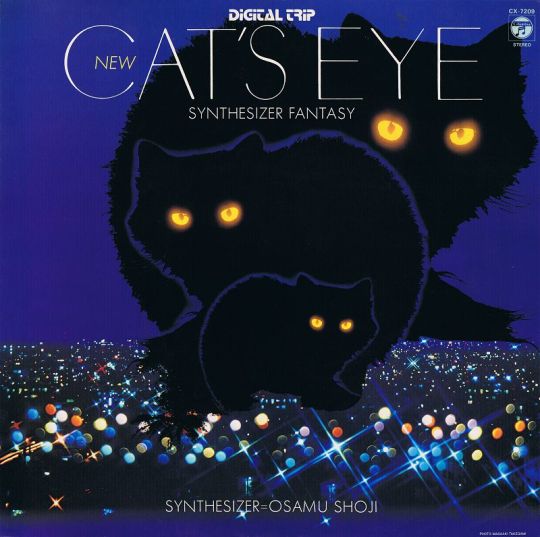

This concept is also reflected in the album art, which tends to feature more abstract designs and lots of futuristic grid lines and shapes that aren’t always obvious reflections of their source anime. Most of the anime selected were science fiction and fantasy given the nature of the concept, but several non-fantasy anime also received albums.

The tracks on DT albums are mostly based on the existing works of composers, but the actual arrangements and performance are handled by different arrangers, with a few exceptions. While the original compositions still influenced how each album ended up, the arrangers played the largest role in shaping them through their own skills and visions. The music in each album ranges from more conventional rearrangements, airy ballads, electro-dance, faster rock, atmospheric soundscapes, longer suites, and a whole host of other styles.

I don’t think any of the DT albums are bad, but the less unique ones fall into the trap of keeping the compositions too similar to the originals. The least interesting tracks sound just like the original songs with the instruments swapped, but those are thankfully rare. While the DT albums can be listened to without any knowledge of their base soundtracks, comparing them with their original scores highlights how creative and varied the rearrangements can be when working with a totally different sonic palette.

At their best, the DT albums strike a balance of being faithful enough that the original compositions are still recognizable while also transforming them such that they stand on their own. Sometimes multiple songs are mixed into larger suites, and other times each vocal song and chosen BGM gets its own track, but each track contains new flourishes and notes that add to the original compositions, as well as going into unpredictable directions and styles. The rearrangements of vocal songs are some of the livelier ones, but part of the enjoyment is seeing all kinds of songs reinterpreted though this “Synthesizer Fantasy” concept.

The Main Arrangers

While there were several one-off arrangers, the Digital Trip series had a rotation of regulars that carried their own styles across multiple albums. A few of the more prominent ones included:

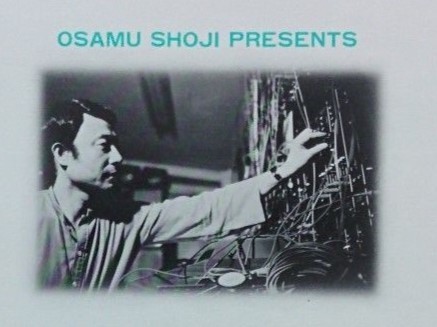

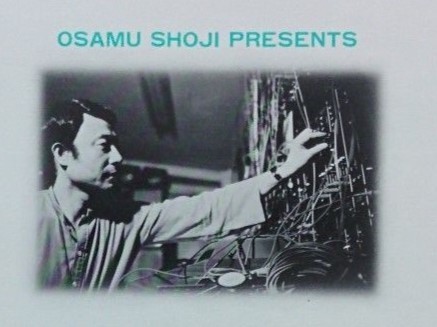

Osamu Shoji (“The Galaxy”): 20 albums

Osamu Shoji was the primary arranger of the DT series and handled a plurality of the albums. As the first and last arranger of the series, his progression throughout the run is interesting to track as he adopted many newer synthesizers and changed his sound the most.

Shoji’s arrangements are mostly straightforward, but that helps them maintain a solid base structure no matter how different the styles are from one track to the next. It reflects his adaptability that he was able to integrate so many different composers and genres into his DT albums that are distinct from both each other and their original soundtracks. Lots of his tracks tend to be more sequenced, but they use that to their advantage to create complex rhythms, tight grooves, and sturdy percussion backing the more active main melodies. His music’s audio mixes sound deep and well-rounded despite their many different sound tones. Shoji remained the most versatile and reliable arranger in the lineup, shaping the bulk of the DT series.

Shoji released many solo electronic albums and other assorted anime image albums, including the two “Synthesizer Fantasy” image albums that were not in DT series. He composed for a few anime including Adieu Galaxy Express 999, Cobra, and Wicked City.

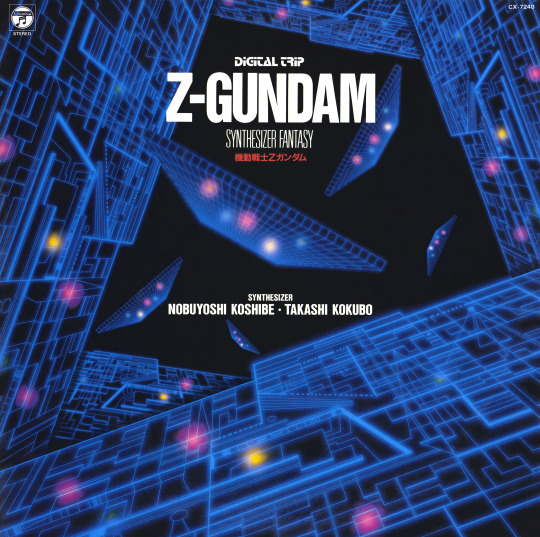

Nobuyoshi Koshibe & Takashi Kokubo: 11 albums + 1 Koshibe solo

The second-most frequent arrangers, Nobuyoshi Koshibe and Takashi Kokubo used some of the wider varieties of synthesizers in the DT series. Their albums have a very crisp and buzzy sound, and their tracks often undergo several instrumental and style changeups throughout. They also feature some of the hardest rocking tracks in the DT series, especially with their louder use of sharper and heavy FM synth tones, but also with very processed, effects-heavy guitars for accents and solos. That said, their albums still have considerable range beyond their rock tracks, with many slower and more atmospheric songs that are gentler when needed.

Koshibe was already an extensive anime vocal song and soundtrack composer prior to the DT series for shows in the 60s and 70s, including giants like Saze-san and Mach GoGoGo/Speed Racer, and he continued working in anisong music afterwards. Kokubo only contributed to one other anime album outside of his DT work, and he was more focused on his solo electronic and new age albums.

Jun Fukamachi: 4 albums

Though his albums were few, Jun Fukamachi had one of the most distinct and beautiful sound palettes in the entire DT series. Compared to the others, Fukimachi’s albums emphasize a much more “live,” almost classical performance with lots of gentle and expressive keyboard flourishes. His arrangements are mostly scarce on percussion and instead aimed for a more symphonic sound with layers of pads and arpeggios backing his sweeping synth leads and solos. While he has more upbeat and harsher songs, most of his works are ethereal and lush. Fittingly, three of his four albums are based on works by Leiji Matsumoto, and his arrangements excel at capturing the grand atmosphere of space opera.

Fukamachi made a couple of other image albums and never composed any anime scores, but he did have an extensive jazz-fusion and electronic career spanning dozens of albums.

Goro Ohmi: 4 albums

Goro Ohmi was more involved in the early run of the DT line. His first few albums have some accompaniment from live instruments while his later ones were more synth-centered. His works are some of the more accessible ones in that they tend towards more straightforward covers that stick closer to the original compositions. Still, they’re solid reinterpretations with enough creative additions. His synths are a touch more primitive than the others, but he still managed to make his arrangements sound full and varied.

Ohmi pivoted to handling many of the Roman Trip albums for Guin Saga, which he continued into the 90s. He composed a few anime and tokusatsu soundtracks afterwards, including Ginga Nagareboshi Gin, Grey: Digital Target, and Hikari Sentai Maskman.

Akira Ito: 2 albums

Akira Ito only composed two image albums of original music near the start of the series before he left the rotation early on. His works are some of the less “digital” in that they contain lots of traditional rock instrumentation, with the synths usually playing only the leads. His style is most akin to 70s progressive rock, with lengthier songs that all flow into each other to form large suites. His two albums have a very fantastical, journeying sound that’s not too representative of the DT line overall but remain interesting outliers.

Ito has a few anime image albums credited to him, but he was more focused on his solo electronic albums that continued this same style.

Appo Sound Project: 2 albums

Appo were a production group of composers and arrangers that arrived near the end of the series, but they still carved out a distinctive treble-focused, more high-NRG sound relative to the others. Their arrangements use sharper digital synthesizers that are very bright in their sound mixes, if occasionally on the thinner side. A lot of their arrangements were more up-tempo and not as subtle, but they have a constant energy that’s still enjoyable, especially in their tracks with multi-suite melodies.

Also of note is that the group features Kohei Tanaka in one of his earlier arranging roles. In fact, a lot of the synth sounds of their work are used in the electronic tracks he composed for his Choushinsei Flashman soundtrack soon after. Tanaka remains one of the most well-known anime composers of all time and went on to compose many, many soundtracks afterwards, though none really sound like his DT work.

Tech

(From the Adieu Galaxy Express 999 DT Album)

Given their concept, the Digital Trip albums are tied to the synthesizer technology of the early 80s, with all their quirks and limitations. The albums are rather accessible for early electronic music, but their sounds are challenging for those not as predisposed to synthesizers. Nevertheless, exploring aspects of the synth technology at the time illustrates the ingenuity needed to make the albums.

Early synthesizers and sequencers were trickier to operate and program compared to later advancements. All settings for sounds had to be individually connected with cables, tuned with knobs, or programmed with basic keypads. On the few units that had them, display screens were minuscule and had few lines. Storage banks were also limited, so saving any sounds to reuse for later often required meticulous notetaking.

Keys on older synthesizers were also not as touch-sensitive, meaning the notes would sound the same regardless of how fast or hard the keys were pressed. Pitch and modulation control were often present but rather basic. Polyphony, or the ability to play more than one key at once, varied widely by keyboards, which also made full chords harder to play.

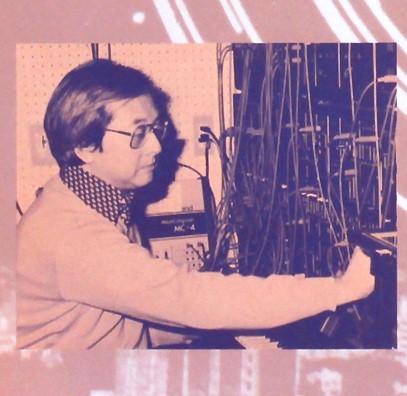

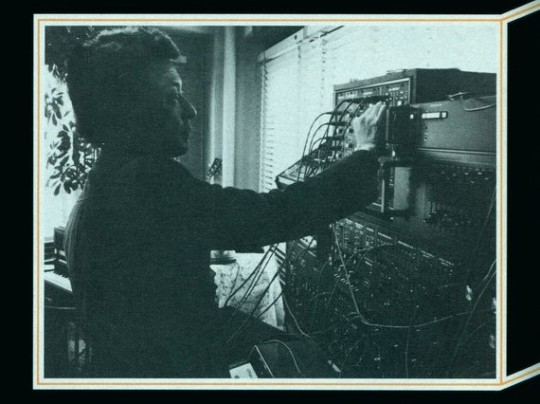

(Osamu Shoji, from the Adieu Galaxy Express 999 DT Album)

Many of the albums were made before the MIDI standard was codified in 1983. Pre-MIDI sequencers had limited interfaces that required all aspects of each note to be programmed individually, though this did allow for finer precision. Timing sequences with live playing was also a challenge for units that had variable sound consistency and different communication formats.

This made configuring each part of a single song with only synthesizers a laborious process, especially for albums that were 30 to 40 minutes long. The arrangers not only had to rearrange the original notes to work within the technical capabilities of each synthesizer they wanted to use, but they then had to make sure each synth was attuned and set up correctly for recording and mixing. Some DT albums have additional engineers credited who assisted with the tedious work of configuring these different systems and note sequences, but the arrangers were still responsible for the bulk of the work in planning and connecting all of these machines.

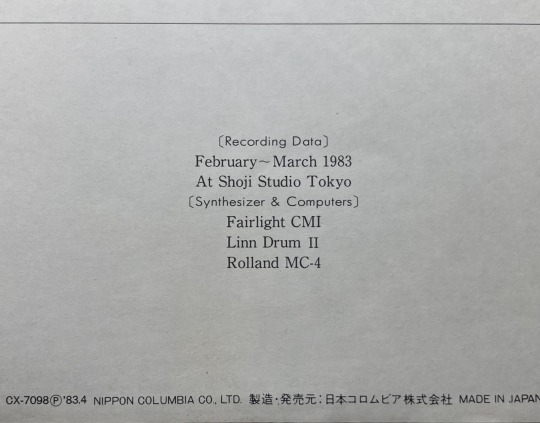

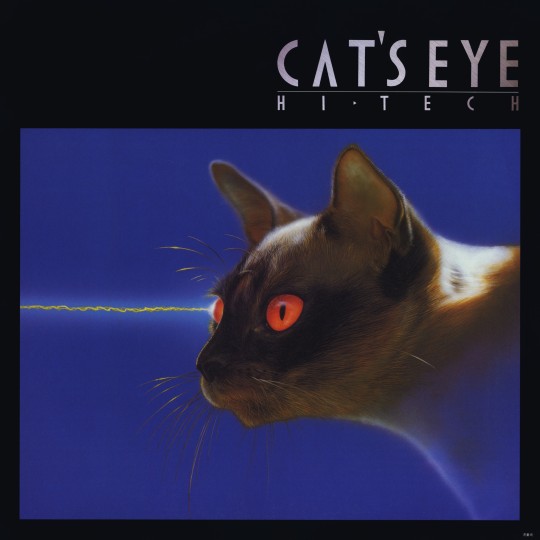

The liner notes for some albums include lists of the synthesizers and instruments used, which also reflect the habits of their respective arrangers. While going over the instruments for every album would be lengthy, comparing two albums that were both released in 1983 yet contained wildly different sounds illustrates these varying sonic approaches.

(Osamu Shoji using the Fairlight CMI, from the God Mars DT)

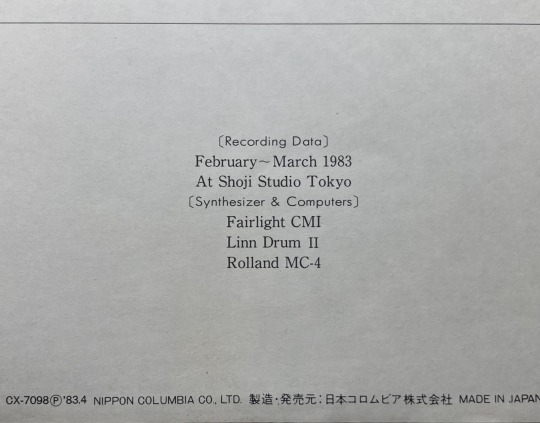

The Macross DT album by Osamu Shoji only lists the Fairlight CMI sampler, the Linn Drum II (the “classic” LinnDrum), and the Roland MC-4 sequencer. This means every non LinnDrum sound on the album is produced just from the CMI’s digital sample library, albeit with his own modifications and even his own sampled noises.

The album’s diverse styles and instruments, from the upbeat pop and action to the grander slow songs, reflect both the CMI’s depth and Shoji’s skill as an arranger and programmer. Shoji’s equipment range is broader on works like his Adieu Galaxy Express 999 and Gundam DTs, but the Macross DT demonstrates how it was still possible to make a wide-ranging album with such a small selection of tools that had expansive capabilities in the right hands.

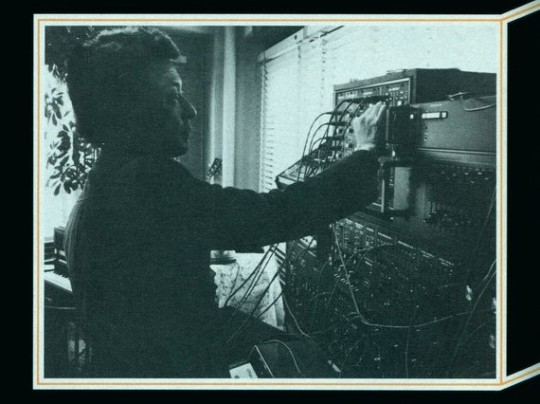

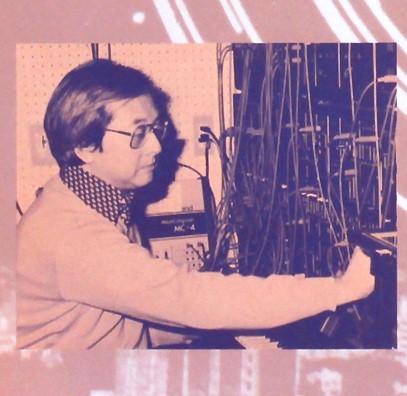

(Koshibe using the Roland System 700 and MC-4)

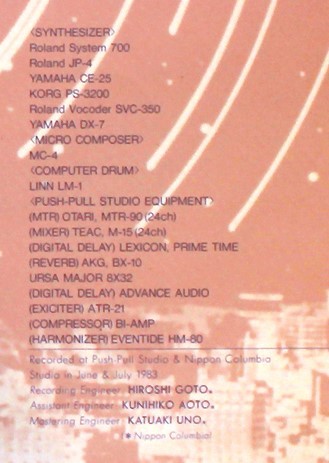

By contrast, the Urashiman DT by Koshibe & Kokubo has a longer and more peculiar list of instruments, and it also includes the recording and mixing equipment. The first synth listed is the analog Roland System 700 from 1976, an older modular synthesizer that required connecting streams of wires between each individual sub-unit and lots of manual tuning to get the desired sounds. A picture in the liner notes shows Koshibe working with both the System 700 and the MC-4 sequencer. The rest of the list contains a mix of synthesizers, both analog (Roland JP-4, SVC-350 vocoder) and digital (Yamaha CE-25, DX-7, Korg PS-3200), with vastly different sound tones, many of which show up across the duo’s other albums. The amount of moving parts to sequence, tune, and play is daunting, but the album’s layered sound reflects this approach well.

Not all the albums list the synthesizers used. Most of Fukumachi’s albums only have a generic “synthesizers” credit, which is frustrating considering how distinct his style is. Some albums have liner notes describing the process and approach taken for every track. The Macross DT liner notes go into the techniques Shoji used with the CMI and sequencers to make the album. I hope to get more of those translated in the future, but the depth of the arranging process is still reflected by the structure of the tracks.

While the technical craft in employing all of these tools is remarkable, there are limitations. Some albums unapologetically use presets that became cliched as the decade went on; the DX7’s tubular bells, the Fairlight CMI’s panflute samples, and the LinnDrum’s tom-toms show up quite a few times. The depth of the sounds and tones varies across the albums and arrangers, and many presets were at lower bit resolutions and sample rates than what future samplers were capable of. However, the use of digital instruments and sometimes recording does give most of the albums a better mix clarity than many of their associated soundtracks.

Knowing about the technical aspects is not needed to enjoy the albums on their own, but it does give deeper insight into how certain sounds and stylistic choices were possible. While it is easy to lump all early synth music of this kind as being generically “80’s,” the actual process was much more varied and evolving. The changing styles in the DT line reflect the technological advancement and programming refinement spreading throughout music at the time, which the arrangers furthered through their continuous work.

Other Uses

While some Digital Trip albums came out long after their respective anime and movies, most were released a short time after the first batches of official soundtracks. This meant they tend to cover music from the earlier episodes of 40-50 episode shows, though a few got sequel albums that covered later music.

Because the DT albums are image albums, their music was not intended for use within their respective anime, especially for shows with more traditional and orchestral soundtracks. I haven’t seen all the anime, shows, and movies with the associated albums, but I have seen enough to know it is exceedingly rare for any DT tracks to appear.

However, there are a few exceptions. Urashiman uses a few tracks from its DT album in some episodes across its endgame arc. The most memorable scene is in episode 45 where a stylish non-binary assassin demonstrates their skills to the villains, set to the DT version of the villains’ vocal insert song. It’s a great choice that makes the scene even punchier. Episodes 46-49 also use other more sweeping tracks from the album to accentuate more dramatic scenes.

Sharivan also starts using DT tracks in episode 35, which uses a lengthy portion of the final song on the album for a heartfelt montage. More of the DT songs are used as insert songs in episodes throughout the rest of the series, making it likely the most extensively used DT album for its respective show. Sharivan does have lots of one-off synthy songs that aren’t the DT songs or on its official soundtrack, but the DT ones are still discernable with a keen ear.

In both cases, the respective shows’ soundtracks already had numerous synthesizer songs, so the DT albums fit more naturally in with the rest of the music. Coincidentally, both shows had their original soundtracks released by Nippon Columbia, but that’s a sample too small to make definitive claims about. Though rare, hearing DT tracks used in the shows is always a nice touch.

(If I ever find other examples of DT tracks used as insert songs, or other people are aware of some, I’ll update this section.)

The End of the Series and the Changing Landscape

The last album released in the Digital Trip series was the Arion album in May 1986. I can’t find a source on why the series ended, and it’s not helpful to throw out baseless speculations on why. That said, the changing landscape around the DT albums is still interesting and reflective of the series’ legacy.

As the 80s rolled along, synths became more conventional parts of anime scores rather than getting used primarily as accents, a change facilitated as the technology advanced and got easier to use. Some of the original novelty of hearing electronic-centered albums was dissipating as some anime scores themselves became very electronic. Nevertheless, the DT series was still dedicated to making unique arrangements on their own that differed from the synth work in their respective anime.

However, other sublines of electronic rearrangement albums began emerging at the same time. The Animage label launched their own line of synth-focused image albums called the HI▾TECH series in 1984, although those albums often included more regular instruments than most of the DT entries. Because both the DT and HT lines were covers and rearrangements, some anime received albums in both lines. The HT series ended its regular releases in 1986, but it released a few other albums over the following years.

Additionally, other electronic-centered image albums were increasingly helmed by the composers of their anime’s soundtracks. As Joe Hisashi’s career began taking off, he started creating synth-focused image albums that were often released before their respective movie scores, in some cases functioning as “prototype” scores as he was still working on the main soundtrack, including ones for Nausicaa and Arion. He continued the practice through the end of the decade with albums like his Venus Wars image album.

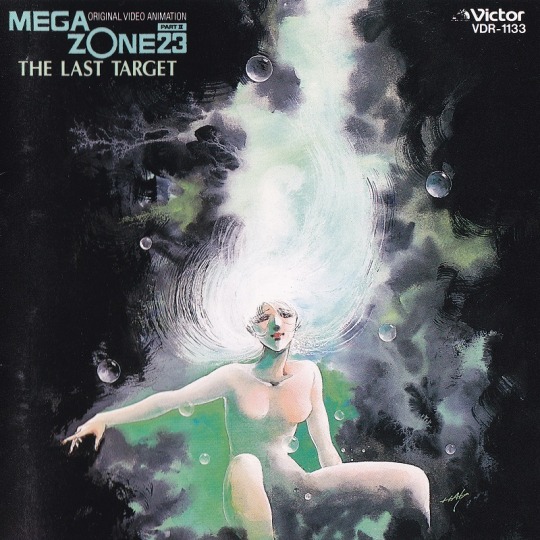

Shiro Sagisu, another then-upcoming composer, took a similar route with his music for Megazone 23 under his TOKIO 23 unit. Megazone 23’s score was already very electronic, but he released two additional synth-heavy image albums in between the releases of the scores for Part I and II that were not only rearrangements, but also contained unique compositions. More composers were feeling confident and adept with synthesizer and electronic music to begin releasing their own image albums in addition to covers from outside arrangers.

The case of the Arion soundtracks illustrates this expanding field. Through the span of year from 1985-6, Arion had its partially synthy movie soundtrack, a Digital Trip album, a Hi-Tech album, and a separate synth “prototype” image album by Hisashi himself, not to mention an even earlier 1983 synthy image album based on the manga that predates the movie score. That’s a huge saturation of Arion synth albums, reflecting how more releases were competing for the same niche the DT series had occupied.

Now, I’ve had enough experience with nonsense internet anime rumors to say that none of this is verifiably connected to the reasons the DT series ended, and it should not be treated as such.

Nevertheless, these circumstances highlight how aspects of the DT series became featured in contemporaneous soundtrack and image albums, which to an extent succeeded the DT line after it ended. More producers, artists, and most importantly, consumers were now acquainted with and enthusiastic about synthesizer music than ever before. Synthesizers were now a core, if not predominant aspect of many anime and popular music albums compared to their marginal use earlier in the decade when the DT series began.

The Digital Trip Albums Now

After the initial run in the 80s, 14 of the albums were remastered onto CD in 1993 under Columbia’s Digital Trip 1800 series. The original LP art was shrunk within a wider blue border, but the booklets mostly contained the same liner notes. 10 of those CDs were reprinted again on CD-R’s under the R-Ban series in 2001.

A few were also remastered onto CD on other compilation releases: the Sharivan DT on the two-disc Sharivan OST and other compilations, both the Yamato and Final Yamato DTs on the Yamato Sound Almanac series, and the Harlock DT in the Harlock Eternal File series, to name a few.

In 2012, Columbia put out a digital-only compilation release that included a few tracks from DT albums that had no CD remasters. Curiously, the release has no tracks from Osamu Shoji and has a large chunk of its tracklist taken up by songs from the Ultraman DT album, except for its final one.

Unfortunately, the majority of the DT albums remain exclusively on their original vinyl and cassette releases and have not seen any official CD or digital transfers, and it is uncertain if they ever will unless Nippon Columbia decides to do so. The 2012 compilation is evidence that Columbia still has the materials available to make remasters for at least a few more albums, but there’s been no sign they’re considering any more.

Somewhat recently, the DT albums in the R-Ban series and two other CD-released ones were officially uploaded to streaming on Spotify, Apple Music, and Youtube Music. (6/5/24: The Sharivan DT was also released as a part of the uploads for the Metal Heroes Super Hero Chronicles, at the end of the fourth album). Curiously, the artwork on these releases is edited to remove all mentions of the phrase “Digital Trip”, both on the title borders and the original album cover. This does result in a few comically empty spaces, like on the Arion cover, but it’s an odd choice since they’re still titled “Digital Trip” in the album names.

As usual for anime fans, the best option to find most of these are through the varying places online. A fair number of them get uploaded to Youtube for the more casual listeners, but the majority are not too hard to find through other sources including conventions, digital stores, and fan rips floating around online.

Conclusion

There’s more to the Digital Trip – Synthesizer Fantasy line and its many albums, but this is about everything I wanted to touch on for now. The albums remain decently well known among retro anime music enthusiasts, but that’s about three layers of niches, so I think I can say that they are still relatively obscure to wider anime fans. The electronic nature of the series is its defining attribute, and that may take some time to get invested in. Still, this is a topic I wanted to cover mainly as a passionate fan but also to provide a decently comprehensive overview of a noteworthy anime image album series.

Synth-focused image albums appeared before and continued well after the Digital Trip series, but it stands as a noteworthy confluence of trends whose arrangers produced many unique, varied, and most of all, engaging albums. A DT album is appreciable irrespective of the original soundtrack it is arranging. Some of my favorite DT albums are for anime I haven’t seen or whose scores I haven’t heard because they were still that evocative on their own. Still, comparing the two highlight interesting aspects of the rearrangements needed to bring the music to synthesized soundscapes.

In the future, I hope to have more of the liner notes from the albums translated to shed even better details on the arranging process. Some of this overview involved generalizing, but I always want to get down to more precise details whenever possible. I may return to covering other aspects of the albums in the future, and I also plan to check out more of the non-DT works from all the respective arrangers.

After this section, I have ten personally recommended Digital Trip albums, in no particular order, as well as additional notes for a few external links, including a playlist of all the officially streaming ones on Youtube.

I encourage anyone interested in anime music, earlier electronic music, or those curious in general to check these albums out. The Digital Trip series is one of my favorite anime image album lines, and I think they carved out a distinct identity that remains interesting even so many years later.

10 Personal Favorites

SDF Macross (Osamu Shoji) – A solid selection of the show’s most famous vocal songs and BGM tracks (although curiously lacking “Watashi no Pilot”) that mixes idol-pop catchiness, fast-paced action, and grander spacey tracks. The bending and expressive keyboard basslines are a huge highlight. The Macross II: Minmay’s Songs album by Koshibe & Kokubo is also an interesting contrast in tech and style. (Translated liner notes for the album are here.)

Uchuu Keiji Sharivan (Koshibe & Kokubo) – My favorite of the Koshibe & Kokubo albums and the first I listened to, this one has lots of very sharp and buzzy FM synth tones. The rare splashes of electric guitars have tons of processing that make them sound roaring. Since Sharivan had a larger album of vocal songs to draw from than most of the other shows, the arrangements here are very lively and go through some fun changeups.

Umi no Triton (Osamu Shoji) – Though much later to its anime compared to the others, this album shines the most in its very catchy beats and rhythmic pulses. While not as atmospheric and sweeping, it still captures an oceanic feel with its twinkling arpeggios and chunky bass. It’s an unexpected combination of styles that works surprisingly well.

Gekkan La La Rensai Hiizuru Tokoro no Tenshi (Akira Ito) – This one is technically closer to the Roman Trip albums since it contains original compositions based off a historical fantasy manga and uses more traditional instruments in several parts. Still, it has a wide range of tracks that all connect into a continuous suite, making it one of the more cohesive and adventurous albums of the DT series, with lots of Japanese-styled instrumentation.

Mechadoc (Koshibe and Kokubo) – An underrated album that reflects the automotive feeling of its anime. Its highest energy tracks capture the grittiness and speed of racing and rally cars, especially some of the sharp FM lead solos, while the more mellow tracks round them out with gentle tones. The songs are lengthy but shift and develop in engaging ways.

Lensman (Osamu Shoji) – As well as having a more futuristic vibe overall, this album really excels with its rapid, complex drum and percussion patterns. Most of the album is a solid combination of upbeat action and funkier tracks, but towards the end there’s slower atmospheric cuts that balance things out.

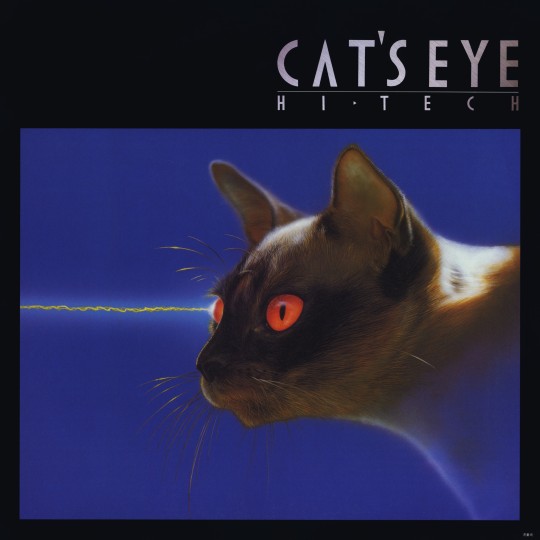

Cat’s Eye (Osamu Shoji) – A more city-pop effort that’s very playful and even cutesy at times, most so with its danceable beats and bouncy basslines. The longer track list also allows for more songs that are focused and succinct. Shoji’s New Cat’s Eye album for the show’s second-season music continues a similar style.

Nausicaa (Junko Miyagi) – From the one-off (and only female) arranger Junko Miyagi, this one is among the most fantastical and soaring of the DT albums, especially with its thick bass pads and whistling tones. It’s also different from the many image albums Joe Hisashi made for Nausicaa, so it’s a good entry point for those already familiar with his music and curious about the DT albums’ overall concept.

Queen Emeraldas/Emeraldus (Jun Fukamachi) – My favorite of Fukamachi’s works, it features some of the lushest arrangements of the entire DT series, including several original compositions. The many glistening arpeggios and gentle keyboards perfectly evoke the feeling of travelling the immense galaxy with tracks that sound both forlorn and blissful. It also comes the closest to feeling like a “live” performance with its subtle, expressive keys.

Arion (Osamu Shoji) – The last DT album released, Shoji showcases his widest range in a lengthy tracklist covering almost every major cue from the movie score. The rapid and rhythmic drums accentuate many tracks nicely, the synth tones have greater depth and layers, and the varied arrangements capture the score’s fantasy atmosphere. It’s a well-rounded and solid album that’s also a fitting sendoff for the series.

Other Links and Miscellany

A playlist of all the officially streaming Digital Trip albums on Youtube, organized chronologically by release date. Lots of the others are available through fan uploads.

VGMDB is an invaluable database for these albums, even if many entries still need more complete details and could always use more contributors and enthusiasts. Note that viewing the full album art and insert scans requires an account.

The aforementioned 2012 Columbia digital release, which has some previews of some other DT tracks.

For a better introduction to synthesizer tech, I can recommend this two-part article from Yamaha on the history of synthesizers and an article from MIDI on the history of sequencing.

This video demonstration of the Roland MC-4 sequencer by Alex Ball is an excellent showcase of its programing process, as well as how arduous it was to make a full sequence. His channel in general is great if you’re into older synthesizers!

For a while only the R-Ban ones were on streaming, but two other CD ones were added to streaming as I was writing this post. Here’s hoping for more!

One oddity MartyMcFlies helpfully pointed out to me; there is a synthesizer album for the Odin: Photon Sailer Starlight film that’s titled “TPO Synthesizer” that has both original music used in the film and synth image covers of the film’s other BGM. “Digital Trip” is printed on the LP label itself, but without the “Synthesizer Fantasy” tagline (instead it’s “Digital Trip Original Soundtrack”). The DT tagline is not mentioned anywhere else in the album, and it does not seem to be included in any listings of the line. He has no idea what the situation behind this weird printing is, but he asked me to mention it regardless. Thanks Marty!

6/5/24:

As a part of the Super Hero Chronicles Albums for the Metal Heroes shows, the Sharivan Digital Trip is also now on streaming at the tail end of the fourth album.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 Year-End Roundup

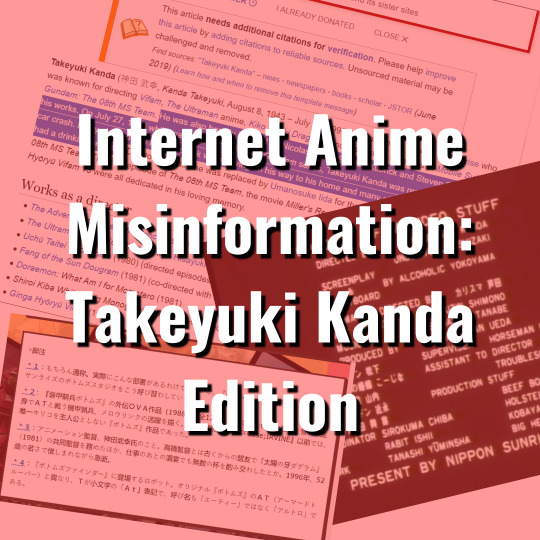

With 2023 winding down, I want to do a short recap on the blog this year. A part of this is to help me evaluate my thoughts and writing with enough hindsight, but it’s also fun to see the weird places I wandered to throughout the year. I wasn’t planning on writing about electronic anime albums, a Gundam guide, and a journey through someone making crap up on Wikipedia, but it all led to some fun diversions, even if I still haven’t settled on a cohesive identity for this blog.

While this blog still wasn’t too active, I’m happy I had the discipline to write, edit, and release multiple posts on varying topics. This is all still a hobby of mine, but it’s good practice for my own writing. I don’t have huge aspirations for this page, but if I can make something entertaining and informative for at least a few other people while exploring my interests, that’s rewarding enough.

The only major change to the blog itself was making it look more presentable. A purple background with white text was a bad idea and I don’t know why I put it in at all, but hopefully the light pink with black text style ages better. Or maybe I’ll decide that look stinks too, we’ll see.

For some reason, neither this nor the Tumblr show up Google’s search, but they do appear on Yahoo and Bing. I’m doing the Google site analytics tools to crawl the URL and see what the issue is, but any advice is appreciated. I don’t want this to be stuck on social media alone, especially since I avoid using it too much.

With all that said, here's my brief recap of what happened here in 2023.

Posts

Diving into the Digital Trip My favorite and longest post that I worked on, this was a chance to explore a true passion of mine, and I’m glad that it got read and shared by others. I’ve loved going through these albums so much over my years of ani/toku song listening, but I noticed there was not a direct English overview of the series as available aside from blogs and scattered forum posts covering a few individual albums. While I hoped to balance providing actual details with some personal opinions, the overarching goal was to have some kind of record (tee hee) of the series.

There is the issue of writing about music without getting to demonstrate it with the actual songs, but I’m skittish about YouTube given my past experience with a fun clips channel that got nuked. Even for the official uploads, I didn’t want to rely on links to videos that could get eventually removed when writing the post. I’ve seen lots of posts that bank on watching a now-deleted linked video as a part of reading it, so I wanted to make the post work well enough on its own.

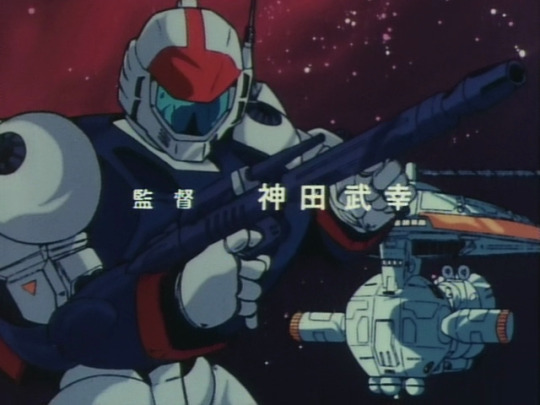

I also regret that I didn’t have enough primary sources to make it a proper “history”, and I disdain having to fall back on generalizations regarding some details like the series’ end. This is something I’d love to revisit again in the future, either as a more specific history or covering a few of the albums in more detail. Still, I enjoyed writing and releasing this one the most, and I hope I can make posts in this style going forwards. A Journey Through an Internet Anime Rumor on Takeyuki Kanda An unexpected post idea that spun out of an offhand Discord conversation that then spiraled into a whole messy chain of tracking wrong rumors, but I think it came out decent. Sometimes I get so fixated on Som winding story that I need to write it out to put my mind at ease, for catharsis if nothing else. While that normally results in longer, meandering slogs I don’t end up releasing, this time it gave me something interesting to talk about, even if it ended up delaying the Digital Trip article.

The ending part is a bit more dramatic and speechifying than what I’d prefer, but I wanted to capture some of my frustrations that come dealing with anime rumors online. I still have an old Genki book a friend loaned years ago, but I do hope to have the time and plan to actually learn more Japanese, for my own education at least.

Toei Took Down My Youtube Channel Self-explanatory. It was more an update for anyone familiar with my old channel than a real “post”, and there’s already loads more significant cases of Youtube’s copyright system being annoying for years. This also taught me why you shouldn’t ignore your inbox for multi-day stretches, even if you really want to.

The Importance of Big Cool Sci Fi Stuff A breezy, if somewhat superficial post that was my first attempt at writing a post that wasn’t a review, publishing a translation, or episode recap/speculation. This was an idea I had nagging at me without thinking of the right way to formulate it, but I guess it was as plain as “big stuff in sci fi is cool”. I’d written argument-styled articles in real life a few times, so I thought this was a good chance to translate that style into something more nerdy and lower-stakes. If I were to write more opinionated stuff on the blog again, I’d aim it something close to this, though perhaps with stronger topics. How to Get Into Gundam While I try to avoid writing things based of things that swim through social media, this started because I’d seen variations of this question pop up so many times. I wanted to make a more concise and direct guide that didn’t overcomplicate something that’s actually rather straightforward. The reductive, but still fairly accurate recommendation is to just follow production order, which is a useful “watch order” approach in almost all cases of franchises, but I think Gundam’s unique situation of being more a thematic umbrella made a guide like this helpful enough on its own, even if it’s less about the shows’ content.

This was intended more as a “how do I approach Gundam” rather than a “which ones are good”, since opinions on show quality are more personal and less helpful to a newcomer trying to explore. Besides, I’ve seen basically every show get praised or slagged by different people, and “fan consensus” is limiting in its own way, if it even exists. I still had some opinion parts fall in there more than I intended, but I think the updated version is better balanced. I don’t know if I could or want to make other guides like this going forwards, but this was a fun diversion regardless. My ideal guide would be something closer to Berndadelta Subs’ guides for Pre-Zyu Sentai and Metal Heroes that talk about aspects and specifics that might appeal to different people, but I hope mine is still helpful to some extent.

(Also, I once accidentally removed the pics from the Blogspot version. Oops!)

G-Witch Episodes 1-6 Recaps These weren’t technically this year, but I figured I’d include them anyways. This was an attempt to have a recurring benchmark to meet, but college eventually caught up with me. I still watched the show all the way through and enjoyed it even after I stopped doing the recaps (and season recaps I tentatively promised), though I felt talking about it with others on Discord was a better way of working through my thoughts than posts like this.

I’m not sure this type of weekly recap is that useful except as a marker of some of my initial impressions. There’s no shortage of takes, opinions, and weekly recaps on anime anyways, so I figure this is something I won’t try again.

Translations (all courtesy of Windii)

Macross DT Liner Notes A supplement to the DT article that gave some of the more concrete details for how the arranging process worked, which was also gratifying for one of my favorite albums in the series. The harmonic math involved on some tracks also highlighted the careful technical knowledge needed for this kind of song arranging. I hope to have more DT liner notes translated in the future.

Newtype August 2023: Ippei Gyoubu Interview on G-Witch’s Costume Designs Sci fi costume design is a longstanding interest of mine, so this was my favorite interview to see translated. A lot of the details also made me appreciate aspects of the show I hadn’t noticed as closely, especially with Suletta’s outfits. Costume design is much more important and deliberate in original anime shows than I had realized, and I’d still love to see more about the other costume designs, especially the Earth House casual outfits and epilogue ones.

Animedia February 2023: Mogmog Interview on G-Witch’s Character Designs This was the first interview I got translated. I wanted to avoid duplicating subjects or interviews other people might do, but I more so chose this article because I loved the designs for the show, especially in that they came from a total newcomer to anime. Mogumo has amazing skills as a character designer and artist, even if the more anime-involved designers played a large role as well, and I enjoyed the character descriptions they were aiming for (especially Suletta and Miorine being dog and cat-like). The interview also showed how involved director Kobayashi was in the process at multiple points, and seeing character details worked out through the design traits is always fun to learn.

I really hope Mogumo and Hisadake can do more anime-related work in the future, especially seeing their designs in new contexts. I bought some of their concept pitch art books digitally, and it seems like they’re also putting out more extensive work at the recent Comiket 103.

Stuff I Want to Tackle in the Future

I don’t have concrete plans for what I’ll tackle in 2024, but there are a few ideas I’ve ruminated over: Translations I feel like so much knowledge about anime is limited because of how much information is out there but goes untranslated, leaving people to speculate (or fabricate) in its place. Learning Japanese is still a far-off goal for me, but I still want to do what I can to get better information about anime floating around through paying people who are good at it (thanks again Windii!). I’ll continue buying some magazines and books myself, but there’s also loads of pages that people have scanned online over the years that are still lying untranslated. Ideally, I want to get more liner notes and older anime magazine articles up throughout the year, though I am still limited by my own finances. More immediately I want to get other liner notes and articles on a few series I like translated, so look out for those in the next months.

Short Opinion/Analysis Articles These would be in the succinct style of the “Big Cool Sci Fi Stuff” article but sometimes focused on more meaty topics. The main one I teased was exploring the way people talk about anime directors, but I’m wary of diving into discussions of fandom habits since it’s too easy to abstract and generalize. Talking about fandom discourse is also less important to me given how ephemeral and subjective it is.

I also want to avoid straight reviews or critical analysis, since I think there’s no shortage of media analysis and criticism online that is still entertaining but less substantive in the longer-term than more fact-centered discussions. I have plenty of opinions on the narratives of anime and enjoy talking with pals and friends about some aspects, but I feel like anime plot discussion is a very saturated field that I don’t have anything interesting enough to add to in longer posts. If I do write something like that, I’d tag it under something like “Ruminations”.

I don’t begrudge the people who make reviews, rankings, or discuss anime plots and themes.

It takes a special skillset to articulate cogent and readable opinions beyond mere quick or angry takes. But I feel like opinions on writing and stories have sucked up too much space in anime discussions for a long time compared to other topics like artistic styles, production history, or broader looks at narrative structure, even if that’s been changing lately. I want to make more unique contributions that are still opinionated but would go beyond the standard habits of critical reviews, hopefully something more unique and useful.

While I know what I want to avoid, it’ll take more time to find more focused topics to write about. Additional retrospective overviews of albums are one possibility, and there are broader aspects of some shows I want to explore beyond more standard critical reviews, but there’s a lot I remain unsure about. Still, I’m optimistic I’ll form something out of this tentative plan.

Animation Links Hub I’m nowhere near the skills and capacities of the many people who talk about animation and art in anime, but I always regret how decentralized many sites, people, and resources are when trying to learn about the craft behind anime. This would ideally be a more centralized hub of links to pages that both I and others could use.

Whatever Else I’m sure there’s other things I’ll think of in the future. Balancing the need to not constrict my scope while still giving my blog some kind of tangible identity is difficult, but I hope I can still make this whole thing distinct enough.

Conclusion

Despite the infrequency, I’m satisfied at what I was able to cover this year. I always want to improve my skills as writer, both creative and informative, and this site has already helped as practice. If I can find continued inspiration, I hope to keep this going at least a few more years. I’m expecting life to get busier next year both in real life work and with other creative pursuits, but I plan to make enough time to make new posts here and expand into different topics.

Here’s to 2024! Thanks, Hambrababy

Linktree with other socials and websites

0 notes

Text

Diving into the Digital Trip

“This series was conceived with the intention of taking impressions from animation, comics, and other visual works and developing them into a completely fresh musical world using synthesizers.”

-Obi Strip Digital Trip Series Description, 1983 (SDF Macross DT, translated by Windii)

Intro

When I first started listening through tokusatsu soundtracks, I was going through the two-disc set for Uchuu Keiji Sharivan’s BGM and noticed that the second disc began with a set of songs titled “DIGITAL TRIP Uchuu Keiji Sharivan SYNTHESIZER FANTASY.” Upon playing those curious tracks, I was greeted with a very electronic, synthesized, and striking series of compositions. They were still recognizable as variations of the OST and BGM I’d heard earlier, yet they sounded almost otherworldly.

Years of anisong searching and listening later, and now as an avid music enthusiast, I’ve plunged into the huge range of the Digital Trip – Synthesizer Fantasy albums. Though only lasting around five years, the series saw many releases from a variety of arrangers offering their own, synthesizer-heavy takes on anime and other Japanese media music.

Some of the albums recently received worldwide streaming releases for the first time, but I wanted to write about this series anyways because of how much I enjoyed listening through and discovering so many favorites. I love synthesizer music of all kinds, especially ones that aim for their own distinctive style. The Digital Trip series is unique among both electronic and anime music, and I think it’s worth highlighting as a creative and entertaining series of albums.

This retrospective is a mix of contextual overview, notes on the styles of the main arrangers, a look at some of the tech used, the end of the line itself, and ten personal album recommendations.

(VGMDB is the source for most of the credits and dates in this post.)

Overview

Digital Trip – Synthesizer Fantasy is a series of instrumental image albums released by the Nippon Columbia record label in Japan from December 1981 to May 1986. 51 albums (and one compilation) were produced for it, with each receiving a simultaneous vinyl and cassette release. At its peak, multiple albums were released almost every month, though the typical schedule had more gaps.

Befitting the name, the albums are synthesizer-focused re-arrangements of vocal, BGM, and image songs for select anime, manga, and even tokusatsu. A few albums have original compositions, but the majority are reinterpretations of existing songs and scores. The albums feature some of the newest emerging synthesizers, samplers, sequencers, and drum machines of their release years, though a rare few have more traditional instruments mixed in. Despite the “digital” name, older analog synthesizers are used on some albums alongside newer digital synths.

Nippon Columbia had other similar image album lines that started running concurrently in 1983. The Jam Trip series is the same concept as the DT albums but with jazz-fusion rearrangements instead of synthy ones, and the Roman Trip series is image songs for manga and books that had not received animated adaptations yet. Some of the early DT albums are original image albums for manga, but they soon switched to covering anime while the Roman Trip line focused on new image songs for non-animated works.

Image albums were common music releases throughout the late 70s and 80s onwards, but the DT series is focused on a more specific, overarching concept of making distinctly electronic renditions. The potential of synthesizers and newer computer technologies was captivating for musicians and audiences across the world at the time, so the DT series served as a chance to both experiment with these new tools and to showcase the kind of layered and unique compositions synthesizers were capable of.

This concept is also reflected in the album art, which tends to feature more abstract designs and lots of futuristic grid lines and shapes that aren’t always obvious reflections of their source anime. Most of the anime selected were science fiction and fantasy given the nature of the concept, but several non-fantasy anime also received albums.

The tracks on DT albums are mostly based on the existing works of composers, but the actual arrangements and performance are handled by different arrangers, with a few exceptions. While the original compositions still influenced how each album ended up, the arrangers played the largest role in shaping them through their own skills and visions. The music in each album ranges from more conventional rearrangements, airy ballads, electro-dance, faster rock, atmospheric soundscapes, longer suites, and a whole host of other styles.

I don’t think any of the DT albums are bad, but the less unique ones fall into the trap of keeping the compositions too similar to the originals. The least interesting tracks sound just like the original songs with the instruments swapped, but those are thankfully rare. While the DT albums can be listened to without any knowledge of their base soundtracks, comparing them with their original scores highlights how creative and varied the rearrangements can be when working with a totally different sonic palette.

At their best, the DT albums strike a balance of being faithful enough that the original compositions are still recognizable while also transforming them such that they stand on their own. Sometimes multiple songs are mixed into larger suites, and other times each vocal song and chosen BGM gets its own track, but each track contains new flourishes and notes that add to the original compositions, as well as going into unpredictable directions and styles. The rearrangements of vocal songs are some of the livelier ones, but part of the enjoyment is seeing all kinds of songs reinterpreted though this “Synthesizer Fantasy” concept.

The Main Arrangers

While there were several one-off arrangers, the Digital Trip series had a rotation of regulars that carried their own styles across multiple albums. A few of the more prominent ones included:

Osamu Shoji (“The Galaxy”): 20 albums

Osamu Shoji was the primary arranger of the DT series and handled a plurality of the albums. As the first and last arranger of the series, his progression throughout the run is interesting to track as he adopted many newer synthesizers and changed his sound the most.

Shoji’s arrangements are mostly straightforward, but that helps them maintain a solid base structure no matter how different the styles are from one track to the next. It reflects his adaptability that he was able to integrate so many different composers and genres into his DT albums that are distinct from both each other and their original soundtracks. Lots of his tracks tend to be more sequenced, but they use that to their advantage to create complex rhythms, tight grooves, and sturdy percussion backing the more active main melodies. His music’s audio mixes sound deep and well-rounded despite their many different sound tones. Shoji remained the most versatile and reliable arranger in the lineup, shaping the bulk of the DT series.

Shoji released many solo electronic albums and other assorted anime image albums, including the two “Synthesizer Fantasy” image albums that were not in DT series. He composed for a few anime including Adieu Galaxy Express 999, Cobra, and Wicked City.

Nobuyoshi Koshibe & Takashi Kokubo: 11 albums + 1 Koshibe solo

The second-most frequent arrangers, Nobuyoshi Koshibe and Takashi Kokubo used some of the wider varieties of synthesizers in the DT series. Their albums have a very crisp and buzzy sound, and their tracks often undergo several instrumental and style changeups throughout. They also feature some of the hardest rocking tracks in the DT series, especially with their louder use of sharper and heavy FM synth tones, but also with very processed, effects-heavy guitars for accents and solos. That said, their albums still have considerable range beyond their rock tracks, with many slower and more atmospheric songs that are gentler when needed.

Koshibe was already an extensive anime vocal song and soundtrack composer prior to the DT series for shows in the 60s and 70s, including giants like Saze-san and Mach GoGoGo/Speed Racer, and he continued working in anisong music afterwards. Kokubo only contributed to one other anime album outside of his DT work, and he was more focused on his solo electronic and new age albums.

Jun Fukamachi: 4 albums

Though his albums were few, Jun Fukamachi had one of the most distinct and beautiful sound palettes in the entire DT series. Compared to the others, Fukimachi’s albums emphasize a much more “live,” almost classical performance with lots of gentle and expressive keyboard flourishes. His arrangements are mostly scarce on percussion and instead aimed for a more symphonic sound with layers of pads and arpeggios backing his sweeping synth leads and solos. While he has more upbeat and harsher songs, most of his works are ethereal and lush. Fittingly, three of his four albums are based on works by Leiji Matsumoto, and his arrangements excel at capturing the grand atmosphere of space opera.

Fukamachi made a couple of other image albums and never composed any anime scores, but he did have an extensive jazz-fusion and electronic career spanning dozens of albums.

Goro Ohmi: 4 albums

Goro Ohmi was more involved in the early run of the DT line. His first few albums have some accompaniment from live instruments while his later ones were more synth-centered. His works are some of the more accessible ones in that they tend towards more straightforward covers that stick closer to the original compositions. Still, they’re solid reinterpretations with enough creative additions. His synths are a touch more primitive than the others, but he still managed to make his arrangements sound full and varied.

Ohmi pivoted to handling many of the Roman Trip albums for Guin Saga, which he continued into the 90s. He composed a few anime and tokusatsu soundtracks afterwards, including Ginga Nagareboshi Gin, Grey: Digital Target, and Hikari Sentai Maskman.

Akira Ito: 2 albums

Akira Ito only composed two image albums of original music near the start of the series before he left the rotation early on. His works are some of the less “digital” in that they contain lots of traditional rock instrumentation, with the synths usually playing only the leads. His style is most akin to 70s progressive rock, with lengthier songs that all flow into each other to form large suites. His two albums have a very fantastical, journeying sound that’s not too representative of the DT line overall but remain interesting outliers.

Ito has a few anime image albums credited to him, but he was more focused on his solo electronic albums that continued this same style.

Appo Sound Project: 2 albums

Appo were a production group of composers and arrangers that arrived near the end of the series, but they still carved out a distinctive treble-focused, more high-NRG sound relative to the others. Their arrangements use sharper digital synthesizers that are very bright in their sound mixes, if occasionally on the thinner side. A lot of their arrangements were more up-tempo and not as subtle, but they have a constant energy that’s still enjoyable, especially in their tracks with multi-suite melodies.

Also of note is that the group features Kohei Tanaka in one of his earlier arranging roles. In fact, a lot of the synth sounds of their work are used in the electronic tracks he composed for his Choushinsei Flashman soundtrack soon after. Tanaka remains one of the most well-known anime composers of all time and went on to compose many, many soundtracks afterwards, though none really sound like his DT work.

Tech

(From the Adieu Galaxy Express 999 DT Album)

Given their concept, the Digital Trip albums are tied to the synthesizer technology of the early 80s, with all their quirks and limitations. The albums are rather accessible for early electronic music, but their sounds are challenging for those not as predisposed to synthesizers. Nevertheless, exploring aspects of the synth technology at the time illustrates the ingenuity needed to make the albums.

Early synthesizers and sequencers were trickier to operate and program compared to later advancements. All settings for sounds had to be individually connected with cables, tuned with knobs, or programmed with basic keypads. On the few units that had them, display screens were minuscule and had few lines. Storage banks were also limited, so saving any sounds to reuse for later often required meticulous notetaking.

Keys on older synthesizers were also not as touch-sensitive, meaning the notes would sound the same regardless of how fast or hard the keys were pressed. Pitch and modulation control were often present but rather basic. Polyphony, or the ability to play more than one key at once, varied widely by keyboards, which also made full chords harder to play.

(Osamu Shoji, from the Adieu Galaxy Express 999 DT Album)

Many of the albums were made before the MIDI standard was codified in 1983. Pre-MIDI sequencers had limited interfaces that required all aspects of each note to be programmed individually, though this did allow for finer precision. Timing sequences with live playing was also a challenge for units that had variable sound consistency and different communication formats.

This made configuring each part of a single song with only synthesizers a laborious process, especially for albums that were 30 to 40 minutes long. The arrangers not only had to rearrange the original notes to work within the technical capabilities of each synthesizer they wanted to use, but they then had to make sure each synth was attuned and set up correctly for recording and mixing. Some DT albums have additional engineers credited who assisted with the tedious work of configuring these different systems and note sequences, but the arrangers were still responsible for the bulk of the work in planning and connecting all of these machines.

The liner notes for some albums include lists of the synthesizers and instruments used, which also reflect the habits of their respective arrangers. While going over the instruments for every album would be lengthy, comparing two albums that were both released in 1983 yet contained wildly different sounds illustrates these varying sonic approaches.

(Osamu Shoji using the Fairlight CMI, from the God Mars DT)

The Macross DT album by Osamu Shoji only lists the Fairlight CMI sampler, the Linn Drum II (the “classic” LinnDrum), and the Roland MC-4 sequencer. This means every non LinnDrum sound on the album is produced just from the CMI’s digital sample library, albeit with his own modifications and even his own sampled noises.

The album’s diverse styles and instruments, from the upbeat pop and action to the grander slow songs, reflect both the CMI’s depth and Shoji’s skill as an arranger and programmer. Shoji’s equipment range is broader on works like his Adieu Galaxy Express 999 and Gundam DTs, but the Macross DT demonstrates how it was still possible to make a wide-ranging album with such a small selection of tools that had expansive capabilities in the right hands.

(Koshibe using the Roland System 700 and MC-4)

By contrast, the Urashiman DT by Koshibe & Kokubo has a longer and more peculiar list of instruments, and it also includes the recording and mixing equipment. The first synth listed is the analog Roland System 700 from 1976, an older modular synthesizer that required connecting streams of wires between each individual sub-unit and lots of manual tuning to get the desired sounds. A picture in the liner notes shows Koshibe working with both the System 700 and the MC-4 sequencer. The rest of the list contains a mix of synthesizers, both analog (Roland JP-4, SVC-350 vocoder) and digital (Yamaha CE-25, DX-7, Korg PS-3200), with vastly different sound tones, many of which show up across the duo’s other albums. The amount of moving parts to sequence, tune, and play is daunting, but the album’s layered sound reflects this approach well.

Not all the albums list the synthesizers used. Most of Fukumachi’s albums only have a generic “synthesizers” credit, which is frustrating considering how distinct his style is. Some albums have liner notes describing the process and approach taken for every track. The Macross DT liner notes go into the techniques Shoji used with the CMI and sequencers to make the album. I hope to get more of those translated in the future, but the depth of the arranging process is still reflected by the structure of the tracks.

While the technical craft in employing all of these tools is remarkable, there are limitations. Some albums unapologetically use presets that became cliched as the decade went on; the DX7’s tubular bells, the Fairlight CMI’s panflute samples, and the LinnDrum’s tom-toms show up quite a few times. The depth of the sounds and tones varies across the albums and arrangers, and many presets were at lower bit resolutions and sample rates than what future samplers were capable of. However, the use of digital instruments and sometimes recording does give most of the albums a better mix clarity than many of their associated soundtracks.

Knowing about the technical aspects is not needed to enjoy the albums on their own, but it does give deeper insight into how certain sounds and stylistic choices were possible. While it is easy to lump all early synth music of this kind as being generically “80’s,” the actual process was much more varied and evolving. The changing styles in the DT line reflect the technological advancement and programming refinement spreading throughout music at the time, which the arrangers furthered through their continuous work.

Other Uses

While some Digital Trip albums came out long after their respective anime and movies, most were released a short time after the first batches of official soundtracks. This meant they tend to cover music from the earlier episodes of 40-50 episode shows, though a few got sequel albums that covered later music.

Because the DT albums are image albums, their music was not intended for use within their respective anime, especially for shows with more traditional and orchestral soundtracks. I haven’t seen all the anime, shows, and movies with the associated albums, but I have seen enough to know it is exceedingly rare for any DT tracks to appear.