Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Final Assessment

Introduction

In our examination of various theoretical schools of thought under the pretense of visual analysis, we have drawn upon the foundational works of Frantz Fanon, bell hooks, Judith Butler, and Stuart Hall. These theorists offer diverse perspectives on identity, power, and representation, which provide a rich framework for understanding the complexities of contemporary media narratives.

Frantz Fanon's psychoanalytic exploration in "The Negro and Psychopathology" delves into the psychological effects of colonialism and racism on the individual psyche. bell hooks, in "Oppositional Gaze," examines visual culture and resistance against the objectifying gaze of white supremacy. Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity, elaborated upon in "Gender is Burning," challenges fixed notions of gender identity. Stuart Hall's analysis of race and representation, particularly in "What is this 'Black' in Black Popular Culture?," illuminates the ways in which racial identity is constructed and negotiated through cultural representations.

Through analysis of the scene from episode 8 of “Watchmen” (2019), “A God Walks Into Abar,” in which Doctor Manhattan chooses his new form, Butler’s theory of gender performativity and bell hooks’ oppositional gaze become clear. The scene in episode 6, “This Extraordinary Being” where Will Reeves transforms into Hooded Justice also serves as a microcosm of the broader themes explored by the aforementioned theorists. Specifically, this scene provides a compelling exploration of race, identity, and power, demonstrating how the characters' actions and interactions reflect and challenge the dominant ideologies and structures of society.

After deconstructing the similarities and differences of each theorist, this synthesized analysis will provide a comprehensive understanding of each scene drawing upon the above theory. We will analyze the characters' internal struggles and emotions, the visual and narrative elements employed, and the broader socio-cultural context depicted in the television series. By applying these theoretical frameworks, we aim to unpack the layers of meaning embedded within the scene, shedding light on the complexities of identity formation, resistance, and representation in contemporary media.

Commonalities

Frantz Fanon, in "The Negro and Psychopathology," delves into the psychological effects of colonialism and racism on the individual psyche. Coming from a psychoanalytical school of thought, he examines how the colonized subject internalizes the dominant culture's perception of their racial identity (1), leading to a sense of inferiority and self-alienation (2). He argues that the colonized subject's desire to assimilate into the dominant culture reflects a form of psychological dependency (3), wherein the white gaze becomes internalized as the normative standard.

bell hooks, in "Oppositional Gaze," builds upon Fanon's ideas by examining how Black women resist the oppressive gaze of white supremacy through acts of visual subversion (4). She introduces the concept of the "oppositional gaze," which refers to the critical and resistant way in which marginalized groups look back at their oppressors (5) (in this context, particularly in media representations). hooks argues that by reclaiming their agency in the act of looking, Black women disrupt the power dynamics inherent in the colonial gaze (6). Her analysis comes from an intersectional feminist school of though, but intersects with psychoanalytic theory through its focus on the gaze as a site of power negotiation, and race theory, as she explores the racialized dynamics of visual representation.

Judith Butler, in "Gender is Burning," shifts the focus to gender identity and performativity. Drawing from poststructuralist ideals, Butler challenges the idea of gender as a fixed and essential category, arguing instead that it is a socially constructed performance enacted through repeated acts (7). Her concept of gender performativity destabilizes traditional notions of masculinity and femininity, opening up possibilities for gender subversion and resistance. Butler's work intersects with both psychoanalytic theory and feminist theory, through her engagement with Lacanian concepts of identity formation, and gender theory, as she deconstructs the binary understanding of gender.

Stuart Hall, in "What is this 'Black' in Black Popular Culture?," examines the complex relationship between race, representation, and cultural identity. Hall explores how Blackness is constructed and represented within popular culture (8), highlighting the ways in which dominant discourses shape perceptions of racial identity. Hall's work intersects with all aforementioned theorists in his exploration of power dynamics, through its focus on the production of subjectivity, and race theory, as he interrogates the politics of representation and identity formation.

Commonalities among all of these theorists include their critique of understandings of identity and identity formation, their emphasis on the role of power in shaping subjectivity, and their recognition of the importance of resistance and subversion in challenging dominant systems of oppression. Additionally, they all engage with the idea of identity as a complex and multifaceted construct that is constantly negotiated and contested within specific historical and cultural contexts, critiquing the power dynamics at play in the formation of identity.

The works of Frantz Fanon, bell hooks, Judith Butler, and Stuart Hall offer valuable insights into the interplay between psychoanalytic theory, queetheory, and critical race theory. By exploring the ways in which identity is constructed, performed, and contested, these theorists provide a framework for understanding the complex dynamics of power, representation, and resistance in contemporary society and popular media.

Differences

While Frantz Fanon, bell hooks, Judith Butler, and Stuart Hall all contribute to the critical examination of identity, power, and representation, they do so through different analytical lenses and with distinct emphases. These variations in approach reflect their unique disciplinary backgrounds, theoretical frameworks, and socio-historical contexts.

Frantz Fanon employs a psychoanalytic lens to analyze the psychological effects of colonialism and racism. His work in "The Negro and Psychopathology" focuses on the individual's internalization of racial inferiority and the impact of the colonial gaze on identity formation. Fanon's analysis is deeply rooted in Freudian psychoanalytic theory, particularly concepts such as the Oedipus complex and the unconscious. His writing style is often existential and introspective, as he reflects on his own experiences and those of his patients to illustrate broader patterns of racial alienation and resistance.

In contrast, bell hooks, informed by her background in cultural studies and feminism, approaches the intersection of race and gender through a critical lens that emphasizes the role of representation and visual culture. In "Oppositional Gaze," hooks examines how Black women resist the objectifying gaze of white supremacy through acts of visual subversion. Her analysis is grounded in the politics of representation, drawing attention to the ways in which images shape perceptions of race and gender. Unlike Fanon's psychoanalytic focus on internalized oppression, hooks foregrounds the agency of marginalized subjects in challenging dominant modes of visuality, focusing on the group rather than just the individual.

Judith Butler, influenced by poststructuralist philosophy and queer theory, offers a radical rethinking of gender identity and performativity in "Gender is Burning." Butler's analysis is characterized by its rejection of fixed and essentialist categories, as she argues that gender is a social construct enacted through repeated, gendered acts. Unlike Fanon and hooks, Butler's work transcends binary categories, opening up possibilities for gender subversion and resistance that extend beyond the confines of traditional identity categories. Rather than focusing on an individual or group, she challenges the notion of gender in our society.

Stuart Hall, with a background in cultural studies, approaches questions of race and representation from a socio-historical perspective. In "What is this 'Black' in Black Popular Culture?," Hall explores the construction of racial identity within the context of popular culture, emphasizing the ways in which discursive practices shape perceptions of race. His analysis is grounded in the politics of representation, but also attends to broader questions of power and ideology. Unlike Fanon, hooks, and Butler, Hall's work is less concerned with individual subjectivity and more focused on the ways in which collective identities are produced and contested within specific cultural contexts.

In summary, while Frantz Fanon, bell hooks, Judith Butler, and Stuart Hall all contribute to the critical examination of identity, power, and representation, they do so through different analytical lenses and with distinct emphases. Fanon focuses on the psychoanalytic effects of colonialism and racism on individual subjectivity, hooks foregrounds the agency of marginalized subjects in challenging dominant modes of visuality, Butler offers a radical rethinking of gender identity and performativity as a construct, and Hall explores the construction of racial identity within socio-historical contexts. These differences in approach enrich our understanding of the complex interplay between race, gender, and power in contemporary society.

Application: “This Extraordinary Being” and “A God Walks Into Abar”

In the eighth episode of “Watchmen” (2019), “A God Walks Into Abar,” there is a scene where Angela has Doctor Manhattan choose a less conspicuous form to present himself as (Kassell, 46:55). Angela presents Doctor Manhattan with various cadavers (which she presumably has access to as a result of her profession as a police officer), asking Doctor Manhattan to choose which form he would like to present himself as. She gives him three options, notably all white men, neglecting to open the last mortuary cooler. Doctor Manhattan, however, opts for Angela to choose for him, stating that what’s important is for her to be comfortable with his form. When Doctor Manhattan brings attention to the unopened locker, knowing that the man she neglected to present to him was the one she preferred, given that he is omnipotent. She opens the locker to reveal Calvin; a man who we know becomes her husband based on previous episodes. Doctor Manhattan then transforms himself into Calvin, and Angela caresses him. He is finally ‘real.’

Frantz Fanon's seminal work, "The Negro and Psychopathology," delves into the psychological effects of colonization and racism on the Black individual's psyche. Fanon argues that Black people often internalize white supremacist ideologies, leading to a fractured sense of self and a desire to assimilate into whiteness. In the scene, Angela's presentation of only white male bodies to Doctor Manhattan reflects a subconscious adherence to societal norms of cultural hegemony. Angela's implicit bias in offering only white options, yet deeper desire for Doctor Manhattan to disguise himself as Calvin, highlights the pervasive influence of white hegemony on perceptions of assimilation and desirability.

Stuart Hall's work on race and representation interrogates the ways in which race is constructed and contested within popular culture. In the scene, Angela's omission of Black bodies from the initial selection reflects broader patterns of erasure and invisibility experienced by Black individuals in media and society. However, Doctor Manhattan's insistence on acknowledging the unopened locker disrupts this erasure, highlighting the presence and significance of Blackness within the narrative. Similarly to Fanon’s psychoanalytical lens, by incorporating Hall’s theory into this scene, we can gain a deeper understanding of racial dynamics present in such a simple moment from this scene.

bell hooks' concept of the oppositional gaze explores how marginalized groups, particularly Black women, resist and subvert dominant narratives through their own gaze. Angela's gaze in this scene is crucial. Despite the options she presents, she subtly asserts her own agency by withholding the final choice, indicating her desire for a form that resonates with her own experiences and desires. By ultimately selecting Calvin, who is Black, Angela disrupts the normative gaze that privileges whiteness and affirms her own subjective desires and identity. This act of resistance aligns with hooks' assertion that marginalized individuals have the power to reclaim their agency and reshape dominant representations.

Moving in a slightly different direction than the theorists above, Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity can be applied to the actions Doctor Manhattan is ‘repeating’ in this scene. His transformation into Calvin underscores the fluidity and performative nature of identity. By choosing to embody Calvin, going so far as to change his vocal cords and height to embody a specific gender ideal, Doctor Manhattan challenges fixed notions of gender and racial identity, suggesting that these categories are mutable and contingent upon context and perception. Angela's love for Doctor Manhattan in a different form further reinforces the idea that identity is not inherent but enacted, suggesting that intimacy and connection transcend physical appearances.

In this scene, each theorist works together to weave together a narrative of internal struggle against a rigid society. What may come across as a simple love story on the surface can actually be analyzed as a complex exploration of race, gender, identity, and power dynamics. By synthesizing these theoretical frameworks, we gain a deeper understanding of the scene's significance and its broader implications for understanding identity and power in contemporary society.

The episode "This Extraordinary Being" from "Watchmen" (2019) tells an extremely visceral and heartbreaking story of trauma and rebirth which we can analyze under the lens of each of these theorists to gain a deeper understanding of the story being told. When walking along the road after a disheartening talk at the station, Will Reeves (who is Angela, experiencing Will’s memories) is approached by his colleagues asking if he would like to join them in the car for a ride home and a beer, (Williams, 45:06). Reeves politely declines their offer three times, and it’s clear that there is something amiss throughout this interaction. After they finally agree that they can grab a beer another time, the officers speed off while dragging two Black men’s bodies on ropes behind them. As Will navigates alleyways to try to escape the officers, the three officers corner him and beat him, dragging his body to a tree as he falls in and out of consciousness, all filmed from a point of view perspective. They hang Will from the tree with a hood over his head, but drop him to the ground just before he can no longer breathe. The officers cut the rope and tell him that next time they won’t cut him down. This pivotal moment marks the turning point for Will Reeves, as he walks the alleyways home with a noose around his neck. He intervenes in an assault taking place in the alley with the hood on his head, as he is now Hooded Justice.

Frantz Fanon's "The Negro and Psychopathology" delves into the psychological impact of racism and colonialism on the psyche of Black individuals, exploring the internalization of white supremacist ideologies. In this scene, the violence inflicted upon Will Reeves by his white colleagues reflects the pervasive racism ingrained within the fabric of society. Reeves's repeated polite refusals to join his colleagues in the car underscore the social boundaries imposed upon him as a Black man, navigating a world structured by white supremacy. The brutal assault and attempted lynching he endures highlight the dehumanization and violence inflicted upon Black bodies by those in power, echoing Fanon's analysis of the psychological wounds caused by racial oppression.

Stuart Hall's exploration of race and representation in popular culture illuminates the significance of Hooded Justice as a symbol of Black resistance and empowerment. Hooded Justice disrupts dominant narratives of heroism and justice, offering a counter-narrative that challenges the erasure of Black experiences from mainstream media. Through his actions, Hooded Justice interrogates the meaning of Blackness and its representation in popular culture, asserting the validity and complexity of Black identities. The scene underscores Hall's assertion that popular culture serves as a site of struggle and contestation, where marginalized groups assert their presence and challenge dominant discourses.

bell hooks' concept of the oppositional gaze offers a lens through which to analyze Will Reeves's response to his trauma and oppression. As he walks the alleyways with a noose around his neck, Reeves transforms his experience of victimization into a catalyst for resistance and empowerment. By donning the hood and intervening in the assault as Hooded Justice, Reeves subverts the narrative of victimhood imposed upon him by white supremacy and asserts his agency and strength. Through his actions, Reeves embodies hooks' notion of the oppositional gaze, reclaiming his agency and challenging the dominant power structures that seek to oppress him.

Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity provides insight into the construction of identity and the fluidity of gender roles and the way in which we change our self-presentation based on societal context and personal experience. Will Reeves's adoption of the persona of Hooded Justice represents a performative act through which he negotiates his identity in response to trauma and oppression. By embodying the figure of Hooded Justice, Reeves transcends conventional notions of masculinity and racial identity (later disguising himself as a White man), challenging fixed categories and asserting his autonomy. The hood becomes a symbol of empowerment and resistance, enabling Reeves to navigate the complexities of race, gender, and power in a hostile world. This scene offers a profound exploration of race, trauma, and resistance, and can be understood on an even deeper level when applying theoretical framework to our analysis. Through the character of Will Reeves and his transformation into Hooded Justice, the scene confronts the legacies of racism and violence while also affirming the resilience and agency of Black individuals.

Overall, both of these scenes explore similar facets of society and power, but with different nuances and focuses. Analysis through the lenses of Frantz Fanon, bell hooks, Judith Butler, and Stuart Hall reveals the intricate dynamics of race, gender, power, and resistance at play. Ultimately, the synthesized examination of these scenes can help to deepen our understanding of the subject matter of the show as well as complexities of identity formation, representation, and liberation within contemporary society.

Conclusion

Reviewing the literature and applying the theories of Frantz Fanon, bell hooks, Judith Butler, and Stuart Hall to the selected scenes from "Watchmen" (2019) unveils a nuanced exploration of race, gender, power, and resistance within the series. Through Fanon's lens, the scenes illustrate the enduring impact of racial oppression on individual psyches, exposing the internalized white supremacist ideologies and the trauma inflicted upon Black bodies. hooks' concept of the oppositional gaze is evident in the characters' acts of resistance and defiance against dominant narratives, reclaiming agency and challenging hegemonic structures. Butler's theory of gender performativity elucidates the fluidity and multiplicity of identity constructions, as characters negotiate and subvert conventional gender and racial norms. Stuart Hall's insights into race and representation shed light on the complexities of Black experiences within popular culture, highlighting the significance of narratives that disrupt stereotypes and affirm the validity of marginalized identities. Together, these analyses deepen our understanding of the series's themes, offering a compelling exploration of identity, power, and liberation within a complex and multifaceted narrative landscape.

(1) Frantz Fanon, “The Negro and Psychopathology” in Black Skin White Masks, 115. Translated by Charles Lam Markmann. London: Pluto Press, 1986. (2) Fanon, “The Negro and Psychopathology”, 140-142. (3) Fanon, “The Negro and Psychopathology”, 145-146. (4) bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 318. (5) hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 308, 313. (6) hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 319. (7) Judith Butler, “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” in Feminist Film Theory a Reader (New York: Washington Square, 1999,) 341-343. (8) Hall, Stuart. "What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?" in Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen, London: Routledge, 1996, 473-474.

0 notes

Text

Analytical Application #6: Race and Representation

Cultural Hegemony

This term, as described by Stuart Hall, refers to the dominance of one cultural group over others, where the dominant culture's values, beliefs, and norms are accepted as the societal norm, shaping perspectives, behaviors, and institutions. Hall describes that cultural hegemony is about “shifting the balance of power in the relations of culture; it is always about changing the dispositions and the configurations of cultural power…” (1).

youtube

In the song “I Wan'na Be Like You" from The Jungle Book (1967), the character King Louie expresses his desire to emulate human behavior and gain access to their power and privileges. The lyrics reflect a longing to adopt the dominant culture's traits and characteristics, symbolized by the "man's red fire," which represents human technology and sophistication.

King Louie's aspiration to "be like you" (i.e., humans) can be equated to the allure and influence of the dominant culture over marginalized groups in our modern society. The song underscores the idea that the dominant culture's values and norms are not only accepted but desired by those on the margins. It reflects the power dynamics at play, where the dominant culture's traits are idealized and seen as a pathway to empowerment and inclusion.

Moreover, King Louie's character, voiced by a white actor (Louis Prima), singing a jazz-inspired song further highlights the appropriation of African American culture by mainstream entertainment. This appropriation perpetuates cultural hegemony by reinforcing stereotypes and erasing the contributions of marginalized groups while simultaneously elevating the dominant culture's influence.

The song's portrayal of King Louie's pursuit of human-like qualities mirrors the broader societal phenomenon described by Stuart Hall as the "shifting balance of power" in cultural relations. It illustrates how cultural hegemony operates not only through overt forms of control but also through the internalization and emulation of the dominant culture's values and behaviors by subordinate groups.

In essence, "I Wan'na Be Like You" serves as a poignant commentary on cultural hegemony, demonstrating how the dominant culture's influence permeates even the realms of fantasy and animation, shaping perspectives, behaviors, and aspirations.

Eurocentrism

Eurocentrism, as discussed by Shohat and Stam, is a worldview centering European experiences as superior (2), while marginalizing non-Western cultures. It prioritizes European perspectives, often distorting or erasing the histories, identities, and contributions of other cultures (3). This perpetuates a hierarchy favoring Euro-American traditions, while exoticizing or relegating non-European cultures to the periphery.

"Everybody Wants to be a Cat" from Disney's original Aristocats (1970) embodies Eurocentrism and cultural appropriation through its portrayal of cats as the epitome of high class and sophistication. The song celebrates the lifestyle and demeanor of the feline characters, who are dubbed as "aristocats," implying a connection between their elegance and European aristocracy.

The song's lyrics and animated scenes depict the cats engaging in leisurely activities such as playing music, dancing, and indulging in lavish feasts. These behaviors align with Eurocentric ideals of refinement and luxury, reinforcing the notion that European experiences are superior and aspirational. However, this song manages to highlight this eurocentric perspective while still appropriating Black culture, using rhythms and chord progressions pioneered by Black communities during blues/jazz movements like the Harlem Renaissance. This notion reinforces the everpresent cycle of the high class adoption of lower class activities making it “cool.”

Furthermore, the characterization of the cats as aristocrats reflects Eurocentric hierarchies, where social status and privilege are closely associated with European cultural norms. By idealizing the cats' lifestyle, the film marginalizes non-European cultures and reinforces the Eurocentric worldview that prioritizes European perspectives while erasing or exoticizing the contributions of other cultures.

The desire expressed in the song's title, "Everybody Wants to be a Cat," underscores the pervasive influence of Eurocentrism, as even non-feline characters aspire to embody the perceived sophistication and status associated with European ideals. This desire to emulate European culture further perpetuates the hierarchy that favors Euro-American traditions, while relegating non-European cultures to the periphery.

In essence, "Everybody Wants to be a Cat" shows how the celebration of European aesthetics and values can reinforce cultural hegemony and marginalize non-Western cultures.

The Orient

As explored by Edward Said, "the Orient" refers to a constructed and exoticized idea of the East, particularly in Western imagination (4). It encompasses a range of diverse cultures and societies from Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, but is often portrayed through Western lenses of stereotypes, prejudices, and fantasies (5).

youtube

The Siamese cat scene from Lady and the Tramp (1955) provides a poignant illustration of the Orientalist lens through which non-Western cultures, in this case, Asian cultures, are often portrayed in Western media. The Siamese cats, Si and Am, are depicted as mischievous, conniving, and inherently villainous characters, embodying a host of stereotypes associated with the Orient.

The scene reinforces Edward Said's concept of the Orient as a constructed and exoticized idea in Western imagination. Si and Am are portrayed with exaggerated features and mannerisms that align with Western stereotypes of Asian people, such as slanted eyes, exaggerated accents, and manipulative or conniving behavior. Their song, "We are Siamese," further perpetuates these stereotypes by employing Orientalist imagery and language, depicting the cats as inscrutable and deceitful, even using a racist voice to depict the characters as well.

Additionally, this scene/song reflects the Western tendency to homogenize and simplify diverse non-Western cultures under a single, monolithic category, as described in Said’s work. Despite the vast cultural diversity within Asia, Si and Am are portrayed as representative of all Asian cultures, reinforcing the Orientalist notion of the East as a homogeneous and exotic "other" to be feared or laughed at.

Furthermore, the scene exemplifies the power dynamics inherent in Orientalist representations, where Western perspectives and fantasies about the Orient are privileged over authentic depictions of non-Western cultures. By reducing Si and Am to caricatures and perpetuating harmful stereotypes, the scene serves to exoticize and marginalize Asian cultures while reinforcing Western cultural hegemony.

This scene exemplifies the Orientalist tendencies present in many representations of Asian cultures in Western media, where non-Western cultures are exoticized, stereotyped, and marginalized through a lens of Western superiority and fantasy.

Popular Culture

Drawing from various perspectives including Stuart Hall's work, popular culture encompasses cultural artifacts, practices, and expressions that emerge from and resonate with the general populace, often shaped by mass media, consumerism, and technology. Hall’s work specifically finds ties between Black culture and popular culture within the US related to tradition, music, and American interests and influence (6).

youtube

The song "When I See an Elephant Fly" from Dumbo (1941) encapsulates the essence of popular culture as a reflection of societal values, traditions, and entertainment preferences. The song, performed by a group of crows, embodies the intersection of popular culture with elements of African American traditions and music, echoing Stuart Hall's exploration of the ties between Black culture and mainstream popular culture.

The style of music used in the scene represents a significant aspect of popular culture at this time, infusing the film with elements of jazz and soulful singing which were integral to African American musical traditions. Moreover, the scene highlights the democratizing nature of popular culture, as it is accessible and relatable to a wide audience. The crows' banter, coupled with the catchy melody, appeal to both children and adults, demonstrating how popular culture and representation of this nature can have a lasting effect on viewers, conforming their understanding of different groups.

Additionally, the scene reflects the role of popular culture in falling under social norms and aligning with various stereotypes. These characters being depicted as crows was certainly no accident. In historical context, Dumbo’s release occurred during times of segregation in the US, specifically regarding Jim Crow laws. The stereotypical depiction of Black culture coupled with the caricature-like representation likely had detrimental effects on the overall depiction and understanding of Black people in the US and beyond.

Overall, "When I See an Elephant Fly" exemplifies how popular culture serves as a dynamic reflection of society, incorporating diverse cultural influences in an entertaining way while also often conforming to the symbolic order perpetuated by the ruling class.

Stereotype

As discussed by Ella Shohat and Robert Stam in their chapter about the very topic, a stereotype is essentially a simplified and often exaggerated representation or image of a particular group, based on fixed and oversimplified ideas or assumptions (7). Stereotypes can be pervasive in media, literature, and everyday discourse, shaping perceptions and attitudes towards individuals or communities. They often serve to reinforce existing power dynamics, perpetuate prejudice, and limit nuanced understandings of diverse identities and experiences (8).

youtube

"What Makes the Red Man Red" from Peter Pan (1953) exemplifies the harmful effects of stereotypes on Indigenous peoples through its simplistic and caricatured portrayal of Native American culture. The song perpetuates stereotypes by reducing Native Americans to one-dimensional characters defined by exaggerated physical features, primitive language, and simplistic behaviors.

The lyrics of the song, with lines like "What made the red man red?" and "Why does he ask you 'How'?", reinforce the stereotype of Native Americans as inherently primitive and mysterious, reinforcing the idea of them as the "other" in contrast to the presumed superiority of Western culture. These portrayals not only simplify and exoticize Indigenous cultures but also perpetuate harmful myths and misconceptions about their traditions and way of life.

Moreover, the song's characterization of Native Americans as comical and childlike further reinforces existing power dynamics, where Indigenous peoples are depicted as subordinate and inferior to Western society. By reducing them to caricatures for comedic effect, the song diminishes the complexity and diversity of Indigenous cultures, reinforcing stereotypes that have been used to justify discrimination and oppression throughout history.

Additionally, the song's portrayal of Native Americans as perpetually stuck in the past, with references to "big chief" and "how," ignores the contemporary realities and contributions of Indigenous peoples, further marginalizing their voices and experiences in mainstream media.

In conclusion, this scene serves as an example of how stereotypes perpetuate harmful misconceptions and prejudices about marginalized communities, reinforcing power imbalances and limiting opportunities for authentic representation and understanding.

(1) Hall, Stuart. "What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?" in Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen, London: Routledge, 1996, 471. (2) Shohat, Ella and Stam, Robert. "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation" in Unthinking Eurocentrism, London: Routledge, 1994, 194. (3) Shohat and Stam, "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation," 200. (4) Said, Edward W.. "The Scope of Orientalism" in Orientalism, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1978, 9. (5) Said, Orientalism, 34. (6) Hall, "Black Popular Culture", 469-472. (7) Shohat and Stam, "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation," 197, 210. (8) Shohat and Stam, "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation," 183.

0 notes

Text

Edward W. Said's "Orientalism" examines the deep-rooted connections between Orientalist narratives and their perpetuation through popular media, while, Ella Shohat and Robert Stam's exploration of stereotypes delves into their role in shaping representations of people in media.

Orientalism, as discussed by Edward W. Said, is intricately interwoven with film, television, and popular media, perpetuating standardized depictions and cultural stereotypes of the "mysterious Orient." Said argues that these mediums often amplify the exoticization and mystification of the East (1), fostering an academic and imaginative demonology that distorts reality (2).

According to Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, stereotypes profoundly shape how people are represented in media, influencing public perception, citing many examples such as racist caricatures as affecting the various perception of various groups (3). They state that subversions of representation in film can “create counterpressure,” (4), essentially stating that by subverting dominant narratives, media representation can have the power to change public perception. As well as this, Shohat and Stam encourage critical engagement with various media (5), citing successful critical analyses as examples, as a means of protest and media literacy to positively affect future productions.

In conclusion, the works of Edward W. Said, Ella Shohat, and Robert Stam's underscore the pervasive influence of media in perpetuating stereotypes and misrepresentations, while also highlighting the potential for critical engagement and counter-narratives to challenge and reshape public perceptions.

(1) Said, Edward W.. "The Scope of Orientalism" in Orientalism, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1978, 34. (2) Said, Orientalism, 16. (3) Shohat, Ella and Stam, Robert. "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation" in Unthinking Eurocentrism, London: Routledge, 1994, 197. (4) Shohat and Stam, "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation", 182 (5) Shohat and Stam, "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation", 182

Reading Notes 10: Said to Shohat and Stam

To wrap up our studies of visual analysis, Edward W. Said’s “Orientalism” and Ella Shohat and Robert Stam’s “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation” provide critical paths to understanding the roles of race and representation play in our production and consumption of film, television, and popular culture.

How is orientalism linked to film, television, and popular media, and in what ways has standardization and cultural stereotyping intensified academic and imaginative demonology of “the mysterious Orient” in these mediums?

What role do stereotypes play in the representation of people, and in what ways can film and television change the perception of cultural misrepresentation?

@theuncannyprofessoro

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analytical Application 5: Gender and Sexuality and "The Sandman"

Gender Performativity

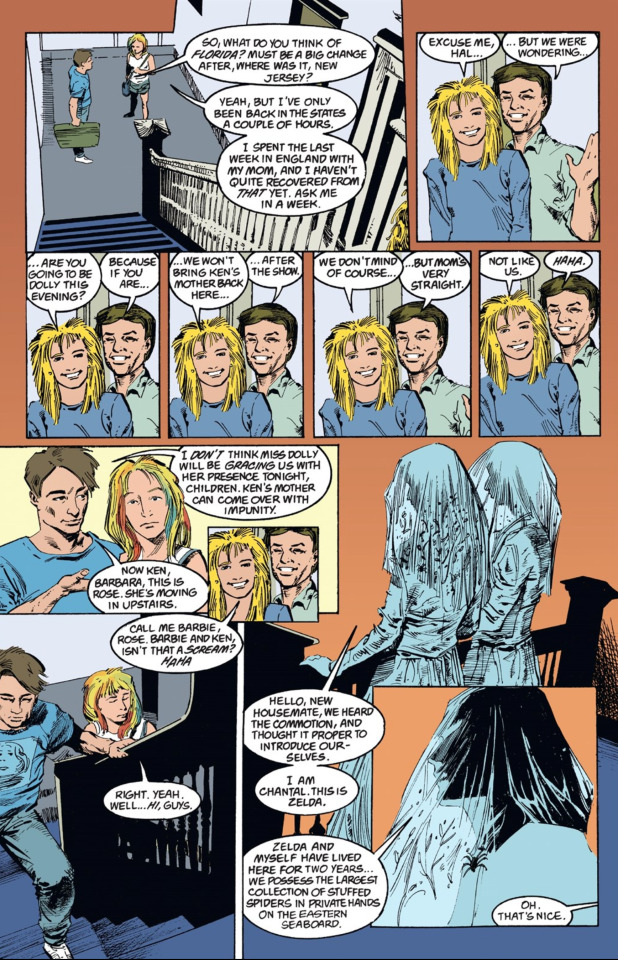

Definition: Central to Butler's gender theory, gender performativity posits that gender is not an inherent trait but rather a repeated performance that creates the illusion of a stable identity. Through acts of expression and embodiment, individuals continually produce and negotiate their gender within social contexts, challenging fixed notions of masculinity and femininity. Butler particularly cites drag as an example of gender performance through participation in gendered acts (1).

Gaiman, 279 & 284

Hal's transformation into Dolly in the chapter “Moving In” exemplifies Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity. As Hal assumes the persona of Dolly, he consciously engages in gendered acts that subvert traditional notions of masculinity and femininity. By donning a short blonde wig, a shining black dress, along with various accessories, Hal/Dolly actively constructs a new, gendered persona for himself outside of his own day to day identity. Through his drag performance, Hal disrupts the idea of a stable and fixed gender identity, highlighting the fluidity and performativity of gender. Dolly's flamboyant and dramatic demeanor contrasts with Hal's persona when initially showing Rose around the house, showcasing the multiplicity of gender expressions within a single individual. This duality underscores Butler's assertion that gender is not an inherent trait but rather a product of repeated performances within social contexts.

Hal's embrace of his drag persona challenges societal expectations and norms surrounding gender, illustrating the potential for subversion and resistance within gender performativity. By participating in drag, Hal/Dolly navigates and negotiates the complexities of gender, offering a glimpse into the constructed nature of identity. Through his performance, Hal/Dolly not only entertains but also disrupts dominant narratives, opening up possibilities for alternative expressions of gender beyond the confines of the sex/gender binary. Overall, Hal's portrayal as both a "normal" landlord and a drag persona highlights the intricate interplay between performance, identity, and social context in shaping notions of gender. His embodiment of Dolly exemplifies Butler's concept of gender performativity, challenging viewers to reconsider and expand their understanding of gender beyond traditional binaries.

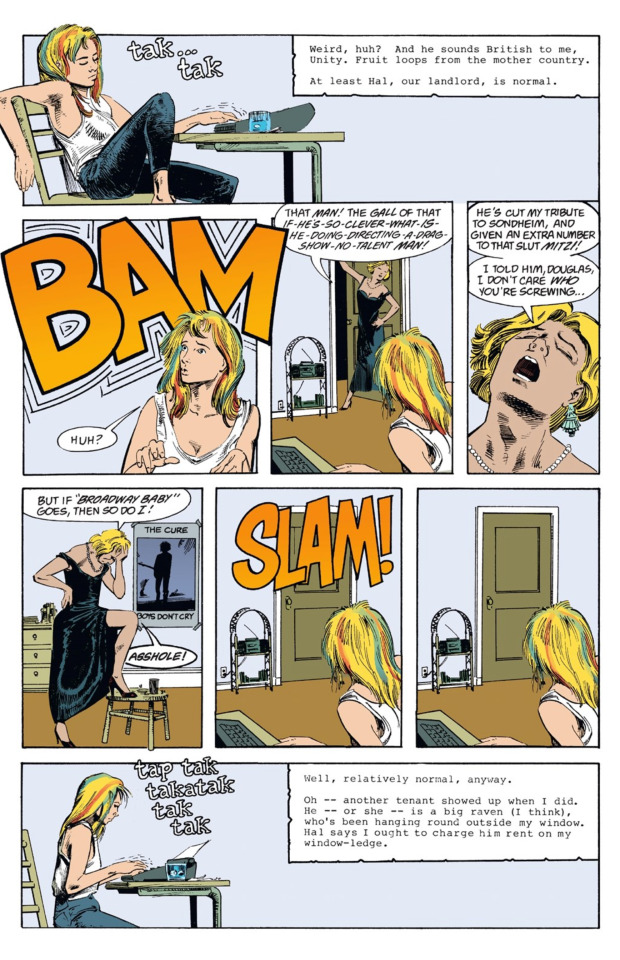

Scopophilia

Definition: Derived from Mulvey's psychoanalytic film theory, scopophilia refers to the pleasure derived from looking and being looked at (2). In her work, Mulvey discusses how cinema often caters to the male gaze, objectifying women as passive objects of desire, thus perpetuating patriarchal norms through visual consumption (3).

Gaiman, 286

In the same chapter, we witness Dream, a masculine-presenting Endless, spying on and gathering information about the Vortex, Rose through his trusty crow Matthew. This scene encapsulates the aforementioned definition of scopophilia quite well. As Dream observes Rose from afar, he not only indulges in the act of looking but also derives a sense of pleasure and control from his voyeuristic gaze. Through Matthew's perspective, Dream objectifies Rose, reducing her to a passive object of desire. Mulvey's theory of scopophilia emphasizes the power dynamics inherent in the act of looking, particularly within the context of patriarchal structures. Dream's observation of Rose reflects a form of visual consumption that aligns with the male gaze, reinforcing traditional gender roles and perpetuating societal norms of objectification. By positioning Rose as the object of his gaze, Dream asserts his dominance and reinforces his own agency while diminishing Rose's autonomy.

Furthermore, the use of Matthew as a conduit for Dream's voyeuristic gaze adds another layer to the scene. As a supernatural entity, Matthew embodies a certain detachment and otherness, allowing Dream to distance himself from the consequences of his actions. This amplifies the sense of control and power that Dream derives from his observation of Rose, reinforcing the dynamics of scopophilia within the narrative. This scene serves as a poignant example of how the male gaze operates within visual media. Through his voyeuristic gaze, Dream perpetuates patriarchal norms of objectification, reinforcing his dominance and control over Rose. Mulvey's concept of scopophilia provides a framework for understanding the power dynamics at play in this scene, highlighting the complexities of gendered representation and visual consumption within "The Sandman" narrative.

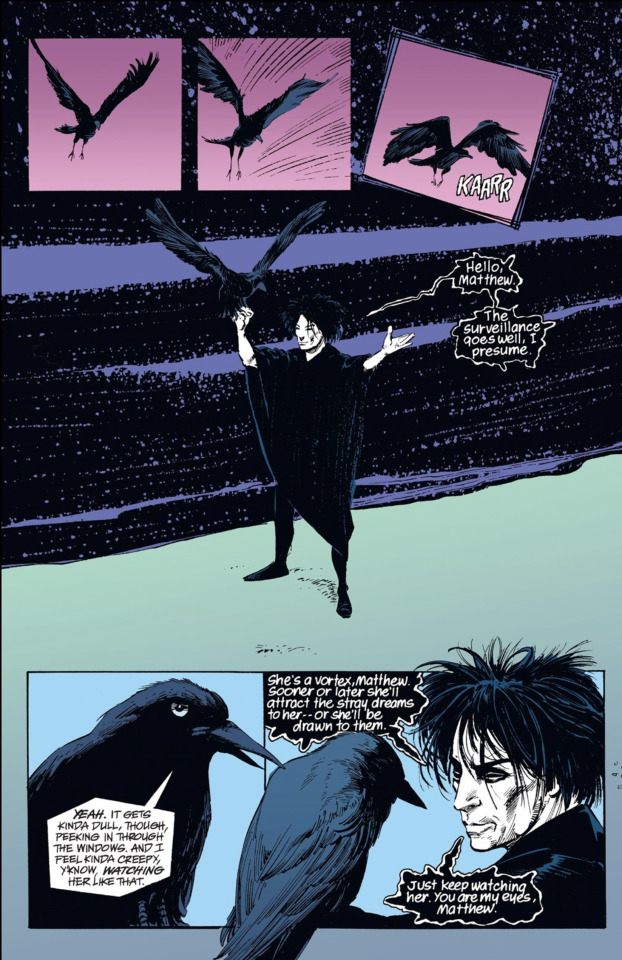

Gender Norms

Definition: Gender norms are societal expectations and standards dictating the behaviors, roles, and attributes deemed appropriate for individuals based on their perceived gender. These norms shape how people express themselves, interact with others, and navigate various social contexts. Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity emphasizes how gender norms are not inherent but are instead constructed and maintained through repeated performances of gendered behaviors (4).

Gaiman, 309-310

In "The Sandman: Book One," the character of Lyta Hall exemplifies the challenges posed by societal gender norms, particularly in the chapter "Playing House." As she grapples with her role in the Dream World alongside her husband, Hector, also known as the Sandman, Lyta finds herself confined by traditional expectations of femininity and motherhood. Lyta's portrayal as the doting wife and expectant mother reflects the gender norms that dictate women's roles within patriarchal societies. Despite her desires and aspirations outside of the domestic sphere (which she can barely think about without her mind going blank), Lyta feels compelled to prioritize her relationship with Hector and fulfill the duties expected of her as a partner. This internal conflict underscores the pressure individuals face to conform to predefined gender roles, even within fantastical realms like the Dream World.

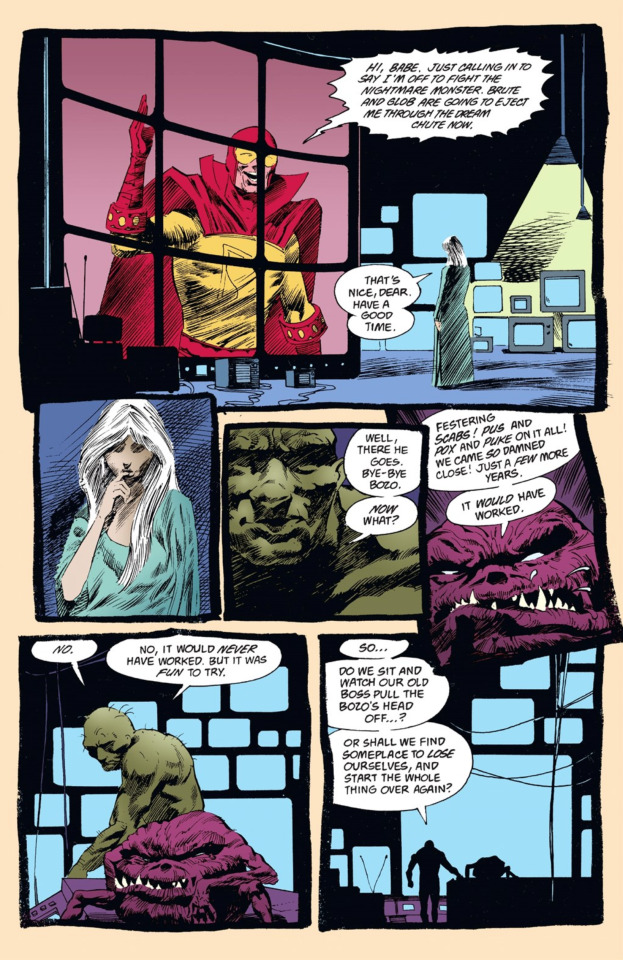

Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity offers insight into Lyta's struggles, highlighting how societal expectations shape and constrain individuals' performances of gender. Lyta's adherence to traditional gender norms is not a reflection of her inherent identity but rather a result of the social conditioning that dictates her behavior within the Dream World. Her reluctance to challenge these norms stems from the fear of deviating from societal expectations and facing potential consequences. Furthermore, Lyta's experience can serve as a critique of the limitations imposed by gender norms, particularly on women's autonomy and agency. Despite her apparent dissatisfaction with her role, Lyta feels obligated to maintain the facade of the dutiful wife and mother, calling Hector “Dear” and telling him to “have a good time” (Gaiman, 310) during his upcoming fihgt, highlighting the coercive nature of gender expectations. Her story reflects the broader struggle for gender equality and the need to challenge and redefine traditional notions of femininity and masculinity in order to create more inclusive and equitable societies.

Subversion

Definition: Rooted in hooks' intersectional feminist theory, subversion involves challenging and destabilizing oppressive power structures. hooks emphasizes the importance of resistance and transformative practices that disrupt dominant narratives of race, gender, and class, fostering empowerment and liberation for marginalized groups (5).

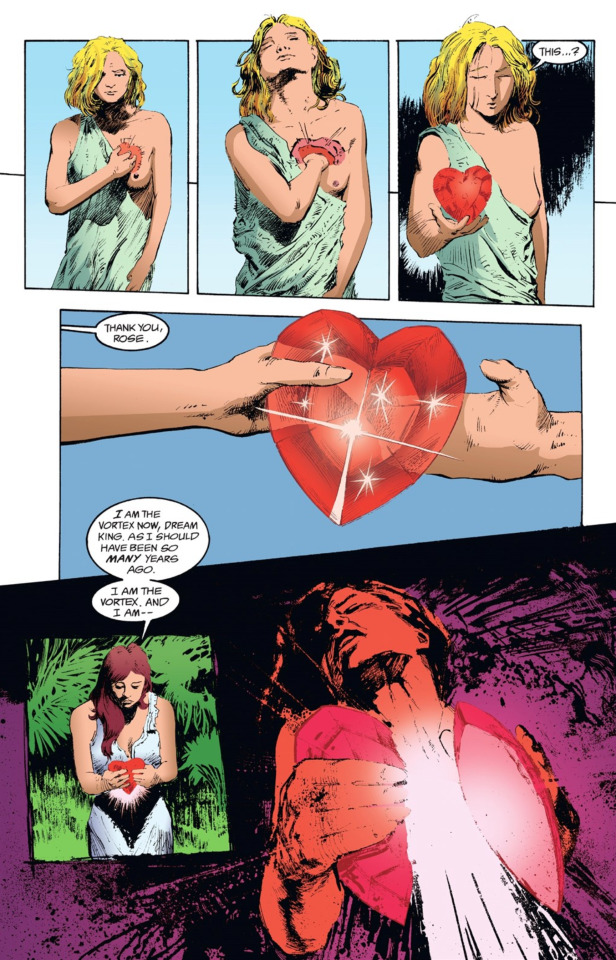

Gaiman, 429

In the scene where Unity confronts Dream in the chapter "Lost Hearts," the concept of subversion, as articulated by bell hooks, is vividly portrayed. Unity's act of challenging Dream's authority and disrupting the narrative he has constructed serves as a powerful example of resisting oppressive power structures. Dream, as a powerful and authoritative figure with control of the Dream World, represents a dominant narrative that imposes control and dictates the lives of others. Unity's decision to confront him directly and refuse to adhere to his decision to kill Rose represents a direct challenge to his power and control. Unity disrupts the established order and asserts her agency. Unity's actions speak to hooks’ words on transformative practices, as she seeks to dismantle the oppressive power dynamics that govern the Dream World. Her willingness to sacrifice herself in order to protect Rose demonstrates a commitment to challenging injustice and fostering empowerment.

hooks' emphasis on resistance and transformative practices is reflected in Unity's actions, as she actively works to destabilize the power dynamics at play. Rather than succumbing to the role assigned to her granddaughter by Dream, Unity chooses to rewrite her own narrative. In doing so, she embodies the spirit of subversion by choosing her own path and carrying on her legacy through her granddaughter. Overall, the scene where Unity confronts Dream in "Lost Hearts" can be viewed as a metaphorical example of the concept of subversion as defined by bell hooks. Through her defiance and refusal to conform to dictated norms, Unity challenges dominant narratives and paves the way for Rose’s freedom.

Sex/Gender Binary

Definition: The sex/gender binary is a societal framework that categorizes individuals into two distinct and mutually exclusive categories: male and female. It presumes a fixed alignment between biological sex and gender identity, neglecting the diversity of sex characteristics and gender identities that exist beyond this binary classification. While she doesn’t address the binary directly, Judith Butler's critique of the sex/gender binary challenges the idea that sex and gender are naturally or inevitably linked. Her work encourages a reexamination of the assumptions underlying the sex/gender binary, advocating for a more inclusive understanding of sex and gender that acknowledges their fluidity and complexity.

Gaiman, 438

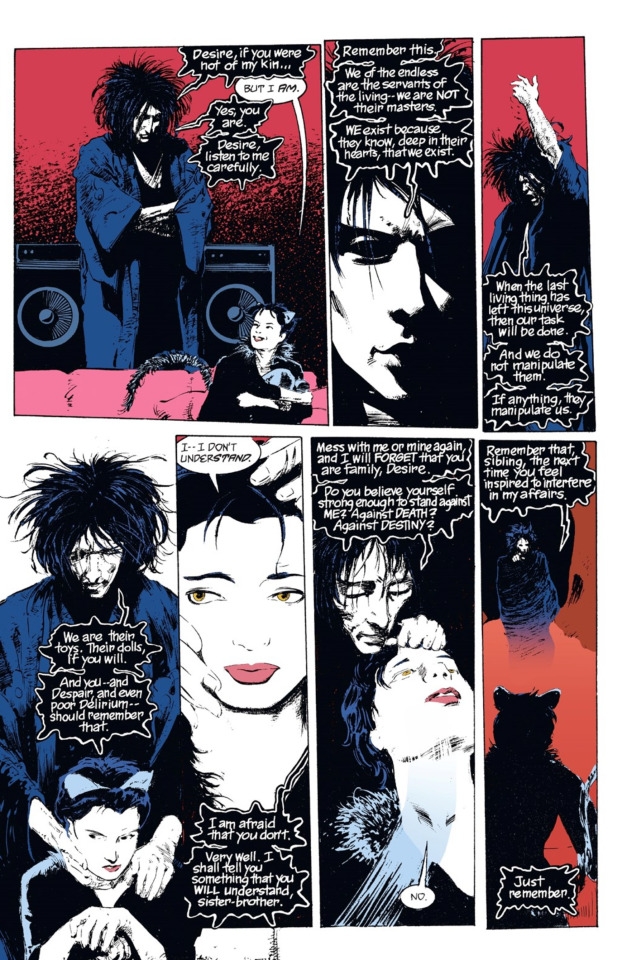

The character Desire directly challenges this definition of the binary described above through their ambiguous and fluid presentation. Toward the end of the same chapter as Unity’s sacrifice, we see an interaction between Dream and Desire where we get a better understanding of Desire’s identity. As one of the Endless, Desire defies categorization within traditional gender binaries, embodying characteristics that transcend fixed notions of male and female.

Desire's depiction as an androgynous being reflects the limitations of the sex/gender binary in capturing the complexity of human identity. Throughout the narrative, Desire is referred to using a variety of pronouns, including "it," "he," and "she," (Gaiman, 439) further blurring the lines between conventional gender categories. This ambiguity challenges the assumption that sex and gender are inherently linked, highlighting the fluidity and multiplicity of gender identities that exist beyond the binary classification. Judith Butler's critique of the sex/gender binary provides a framework for understanding Desire's character, emphasizing the constructed nature of gender identity and the limitations of binary thinking. By embodying traits that defy traditional gender norms, Desire disrupts the idea of a fixed alignment between biological sex and gender expression, encouraging readers to question and challenge existing notions of gender.

Furthermore, Desire's ability to impregnate Unity (as Dream finds out on page 437) further destabilizes traditional conceptions of gender and reproduction. This act challenges the notion that biological sex determines one's capacity for reproduction, highlighting the complexity of human sexuality and the ways in which it transcends binary categorizations.

(1) Judith Butler, “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” in Feminist Film Theory a Reader (New York: Washington Square, 1999) 338-339.

(2) Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism (New York: oxford University Press, 2009), 713.

(3) Mulvey, "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," 719.

(4) Butler, "Gender is Burning," 338.

(5) bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 318.

0 notes

Text

In Jack Halberstam’s exploration of butch representation in film and Stuart Hall’s examination of Black popular culture, we witness the intricate relationship between marginalized identities, representation, and power dynamics.

In “Looking Butch”, Halberstam explains the history of “positive images” in queer representation in cinema, and talks about the skewed representation of various marginalized groups as a result (1). An example which he cites is Vasquez’s role in *Aliens* (1986), where her character contributes to stereotypes across her racial and gender identity and presentation (2). While these stereotypes are played into in the film, Vasquez’s character is still played as a ‘badass independent Latina woman’ (despite her being played by a White woman). This “positive” depiction lacks intersectional awareness and contributes to the idea of positive images as discussed by Halberstam.

Cultural representations serve as contested terrain where power dynamics play out (3). Through our studies, we have learned that popular culture not only reflects societal norms but also shapes and reinforces them. Hall notes that some cultural strategies have the ability to “shift the dispositions of power,” (4). He notes that the hegemonic shift of high culture (5) occurred as a result of the ruling class using these cultural strategies which he describes (6).

In synthesizing Jack Halberstam's analysis of butch representation in film with Stuart Hall's examination of Black popular culture, we discern the intricate interplay between marginalized identities, representation, and power dynamics. These theorists illuminate how cultural representations both reflect and perpetuate societal norms, underscoring the need for intersectional awareness in challenging hegemonic structures.

(1) Halberstam, Jack. "Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film." in Female Masculinity, London: Duke University Press, 1998, 179.

(2) Halberstam, “Looking Butch”, 181.

(3) Hall, Stuart. "What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?" in Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen, London: Routledge, 1996, 471.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Hall, "Black Popular Culture", 468.

(6) Hall, "Black Popular Culture", 471.

Reading Notes 9: Halberstam to Hall

Jack Halberstam’s “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film” and Stuart Hall’s “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” link our inquiries into gender and sexuality with race and representation.

What examples of “positive images” of marginalized peoples are in film and television, and how can these “positive images” be damaging to and for marginalized communities?

In what ways is (popular/visual) culture (performance) a complicated and political site where various identities are negotiated, and how can cultural strategies make a difference and shift dispositions of power?

@theuncannyprofessoro

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Power and privilege play a crucial role in shaping relations among individuals and institutions, as elucidated by both Audre Lorde and Judith Butler. These dynamics often lead to the oppression and marginalization of certain groups based on factors such as race, gender, sexuality, and class. Lorde's notion of using the master's tools to dismantle the master's house suggests a critical reflection on how oppressive systems can be both perpetuated and challenged within marginalized communities. Lorde particularly highlights the importance of difference when looking at what is valued throughout history (1). Similarly, Butler's examination of gender performance highlights how cultural, societal, and media representations reinforce and complicate gender norms. Butler discusses the construction of gender and the societal associations we make with gendered actions (2). Acknowledging and examining oppression and marginalization require a nuanced understanding of power dynamics. Lorde emphasizes the importance of recognizing and utilizing the agency within marginalized communities to challenge oppressive structures. This involves creating spaces for community and dialogue, advocating for intersectional approaches that address the complexities of identity and power (3).

Gender performativity is all around us, all of the time. Butler's concept of gender as a performative act underscores the idea that heterosexuality, like other gender identities, is not inherent but constructed through repeated actions and cultural representations. Heterosexuality, therefore, becomes a performance within the context of societal expectations and norms (4). Overall, both Lorde and Butler explore the relationship between gender and power, but with varying perspectives. Lorde offers a feminist’s perspective on oppressive systems and provides tools to combat this issue, while Butler particularly explores gender as a construct and its effects on society.

(1) Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tool Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” in Sister Outsider (Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press, 1984), 114. (2) Judith Butler, “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” in Feminist Film Theory a Reader (New York: Washington Square, 1999,) 337-338. (3) Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tool Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” 122-123. (4) Judith Butler, “Gender is Burning,” 338-340.

Reading Notes 8: Lorde to Butler

In our continued discussions, Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” and “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” and Judith Butler’s Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” provide further introspection into systems and definitions of gender and sexuality.

How do power and privilege impact the relations people have with each other and with institutions, and how can we acknowledge, examine, and remedy oppression and marginalization using oppressive and marginalized systems?

How do cultural, societal, and media representations support gender performativity and in so doing complicate gender norms, and in what ways is heterosexuality a performance?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I find a lot of Megan’s work recently to be such a cultural reset in terms of reclamation. Especially the aesthetics she used in this video (particularly in the intro) really stood out to me. I found the senator character being representative of participants of the male gaze (and critics of Megan’s sexuality) to be very effective, along with the dichotomy of 50-60’s fashion and sexual liberation. I think I find this video to be more nuanced and effective than Telephone in terms of its commentary on female sexuality and agency, though Telephone was definitely the blueprint.

I also wanted to note how the female characters were also participating in traditionally female acts such as being waitresses, secretaries, shopping, nursing, etc. but with the added element of sexuality. Thanks for such a great discussion you two!

Panel Presentation: "Telephone" and "Thot Shit"

youtube

“TELEPHONE” LADY GAGA & BEYONCE

In Lady Gaga’s “Telephone” (ft. Beyonce) music video, she centers two women criminals, half of the video taking place at a women's prison and the other half following the homicide the women (played by Gaga and Beyonce) set out to commit. The first striking thing about the video is the immediate use of women’s bodies. All the women in the prison are wearing revealing outfits, even the women security guards. As Gaga walks down the cells, the fellow prisoners (all female-presenting) hoot and holler and as character is thrown into her cell, the guards promptly rip off her clothes. This is an example of the use of a woman’s body that is not centering the male gaze. While a male gaze still may derive pleasure from the revealing costumes in the video, these characters are not necessarily designed to be seen as sexy by the male spectator. In Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” she writes that media depictions of women in a patriarchal culture stand as a signifier for the male other - meaning that women characters are present to engage with the male fantasy (1). While most of the women in the music video are partially nude or in revealing costumes, they are not doing so in a sexual nature. Their nudity and sexuality isn’t aiming to please men but to claim their own sexual identity. Mulvey also touches on how women’s bodies in “alternative cinema” can be also a radical or political aspect that challenges the basic assumptions of mainstream media, instead of just being objects for pleasure (2). Women’s bodies are shown in “Telephone” in different ways than usual music videos – there is more of a diversity in beauty and a roughness to them – these bodies are asking to be looked at.

In hooks’ “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” she writes about the “right to gaze.” Specifically, she references: “the politics of slavery, of racialized power relations, were such that the slaves were denied their right to gaze” (3). In these racialized power relations, she writes that Black people were not permitted to engage in the same freedom of watching, entertainment, or deriving pleasure from what they were seeing. This structure ultimately permeates to this day, as hooks writes that of the Black women she spoke to, none were excited to attend the movie theaters, knowing they would not be properly represented (4). How “Telephone” works in contrast with this trend is allowing spectators to look at and derive pleasure from the woman’s body. The idea of the oppositional gaze is a major part of the video because it challenges the ideas of dominant images that women must conform to. The video’s way of resisting the hegemonic gaze was to place the power into the hands of the women characters and for their bodies and strength to be shown without comparing it to that of a male character. hooks references Manthia Diawara to talk about the power of the spectator: “Every narration places the spectator in a position of agency; and race, class and sexual relations influence the way in which this subjecthood is filled by the spectator” (4) (309). Each person, specifically women, watching this music video could feel a sense of agency after experiencing women characters having power over their own bodies.

On the topic of bodies, the music video employs a semi-diverse cast of women in the video (the majority of women in the video are still white). Specifically, a lot of the women have stark differences about them like ethnicities, age, or sexual identity. In Audre Lorde’s “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” she writes that emphasizing differences is usually taught to be bad or ignored, “or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change” (5). In “Telephone,” the differences between these women in prison or Beyonce and Gaga as criminals is distinctly outlined. It is unclear with what Gaga and the writers of the video were trying to accomplish with the “outsider-ness” of the characters in the video – if they were trying to make them look bad or powerful –but one could argue that these women could fit into the archetype of rebels, not caring about society’s rules for them, and that would empower the viewer. It could also be argued that these women are represented by a stereotype of women in prison: violent, erratic, and their homosexuality coming off as predatory and creepy. Mulvey references those who have stood “outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference” (6). “Telephone” puts examples in its video of women on the “margins of society,” but their purpose of being there is unclear to the viewer.

Questions:

Do you think that the other women in the video are meant to be powerful or other-ed, just perpetuating a stereotype?

Do you think “Telephone” practices using the “oppositional gaze”?

How do you think the sexual nature of woman characters in the video differs from other media depictions we have seen?

youtube

“THOT SHIT” MEGAN THEE STALLION

At the beginning of the “Thot Shit” music video, the character of the senator is shown leaving a hate comment on one of Megan’s former music videos (“Body”). When he receives a phone call from Megan she tells him “the women that you are trying to step on are the women you depend on. They treat your diseases, they cook your meals, they haul your trash, they drive your ambulances, they guard you while you sleep. They control every part of your life. Do not fuck with them.” This quote is then the theme for the rest of the video. As the senator tries to escape, Megan and her dancers have taken over every occupation and are dancing in his face. Something interesting in this video is the idea of scopophilia that the senator is taking part in. While he is at first closing his blinds and leaving hate comments before gazing, now Megan and her dancers are forcing him to look, owning their image. Mulvey writes about scopophilia in media/cinema, especially tasteful/pleasurable looking (7). While so much of scopophilia in mainstream media is about privacy and what’s “implied,” it could be argued that Megan is subverting the narrative by using her body and her dancers’ bodies freely and without concerns of what is “forbidden.” It could be seen as an act of agency.

hooks herself may argue that “Thot Shit” is an example of Black women having that sense of agency – the Black women throughout the video have multiple careers while also having the freedom of sexuality. She writes: “Spaces of agency exist for Black people, wherein we can both interrogate the gaze of the Other but also look back, and at one another, naming what we see” (8). This quote encapsulates “Thot Shit” perfectly: a place that Black people can exist freely while also interrogating the gaze of the other. The music video is special because it is a way that Megan celebrates Black women but also the integral part that Black women play in society. They are portrayed as critical parts of a working society but also they dance in the video, owning their sexuality. The sexual nature of the women in the video ties to another example of hooks’ writings about Black women in film/media: the absence “that denies the 'body' of the Black female so as to perpetuate white supremacy and with it a phallocentric spectatorship where the woman to be looked at and desired is ‘white’” (9). hooks writes that too often Black women have been denied ownership and agency over their own bodies, but also the ability to be desired by white phallocentric audiences. By using the character of the senator, they show the inherent racism imposed against Black women - people criticize them but then still sexualize them. Something important to mention is Megan’s lyricism in this song - the word “thot” was coined in the hip-hop world as a derogatory term for a woman, similar to the word “slut,” “with added derision for being working class” (10) (WaPo article). The reclamation of this term is outright powerful because it is using a word that has been weaponized against Black women for years and she repurposes it to be something powerful. This subversion in itself can be tied to the work of the oppositional gaze - taking something used to oppress Black women and flipping it to empower them instead.

Rarely in popular media as big as “Thot Shit” do viewers see something with such a clear message. Megan does include a lot of Black female empowerment throughout her music and music videos, especially through sexual agency. Lorde writes, “Black women and our children know the fabric of our lives is stitched with violence and with hatred, that there is no rest. We do not deal with it only on the picket lines, or in dark midnight alleys, or in the places where we dare to verbalize our resistance. For us, increasingly, violence weaves through the daily tissues of our living … ” (11). “Thot Shit” is a form of protesting against the dehumanization and oppression of Black women in mainstream culture. Megan consistently brings Black women into the cultural conversation when they are neglected. Her empowerment is similar to that Lorde writes of: “It is learning how to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common cause with those others identified as outside the structures in order to define and seek a world in which we can all flourish” (12).

Questions:

What are other ways that “Thot Shit” practices scopophilia and voyeurism in nuanced ways?

How is the video different from other music videos you have seen before?

How does “Thot Shit” work in conjunction with “Telephone”?

Works cited:

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism, 712. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 712

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory, 307. (New York: New York University Press, 1999)

hooks, bell “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference." In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 112. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007

Lorde, Audre “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” (112)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 308

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

O’Neal, Lonnae, “I had a thot but didn’t know it was a thing” The Washington Post, March 19, 2015

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 119

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” (112)

@theuncannyprofessoro

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it’s really interesting that Lady Gaga’s music video ‘defied’ Mulvey’s definition of the male gaze while still sexualizing the female figures in the video. It reminded me a bit of Charlie’s Angels in a way; women being badass but being sexy while doing it. Speaking to Butler’s interpretation of feminized acts, I thought it was notable that the characters in this video were engaging in traditionally masculine acts in a feminized (and sexualized) way. Why do you think this is? Does this contribute to or fight against the male gaze?

Panel Presentation: "Telephone" by Lady Gaga ft. Beyoncé & "Q.U.E.E.N." by Janelle Monáe ft. Erykah Badu

By Sophie Goldberg

youtube

"Telephone" by Lady Gaga ft. Beyoncé

The music video Telephone by Lady Gaga ft. Beyoncé serves as a continuation of "Paparazzi", where Gaga was arrested for killing her abusive boyfriend by poisoning his drink. It features a storyline where Lady Gaga is imprisoned but eventually escapes with Beyoncé's help, and they then go on to poison Beyoncé’s boyfriend and others in a diner and run from the police.

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”

Mulvey discusses the concept of the male gaze, where the camera represents the perspective of a heterosexual male viewer, objectifying female characters for the pleasure of the male audience. Beyonces and Lady Gaga’s portrayal aligns with certain aspects of the male gaze. The music video inevitably attracts male attention as the camera frequently lingers on their bodies and costumes, emphasizing their sexuality and allure. Mulvey states “Traditionally, the woman displayed has functioned on two levels: as erotic object for the characters within the screen story, and as erotic object for the spectator within the auditorium” (716). For example, when Lady Gaga first enters the prison everyone is wearing revealing clothes, and as she's pushed into her cell officers strip her down, leaving her with nothing but fishnets. Another instance occurs when Lady Gaga and three other women wear studded bikinis and engage in a provocative dance down the prison corridors. Spectators also see them through the lens of a security camera, furthering the voyeuristic aspect.

However in "Telephone," both Lady Gaga and Beyoncé also challenge traditional notions of passive femininity by taking on assertive, dominant roles. Mulvey states that “pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female’ (715). Women are presented as spectacle as the man's role is “the active one of forwarding the story,” (716) Lady Gaga and Beyoncé disrupt traditional narrative conventions by defying societal expectations of female passivity and instead taking control of their own narrative. Gaga and Beyoncé portray themselves as empowered and even dangerous figures as in the music video there are depicted acts of violence against men.

Bell Hooks, “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators”

Hooks discusses how Black female spectators often engage with media representations critically as “ mass media was a system of knowledge and power reproducing and maintaining white supremacy. To stare at the television, or mainstream movies, to engage its images, was to engage its negation of black representation.” (308) In "Telephone," Beyoncé's confident demeanor, assertive actions, and her role as the one with more agency than Lady Gaga—having the power to bail her out of jail—can be viewed as empowering examples of Black women asserting their autonomy within mainstream media.

Furthermore, Hooks critiques mainstream media for its tendency to eroticize and objectify Black women's bodies. In the video, there is a moment in which there is a high angle shot of Beyoncé's cleavage as she sits across from her boyfriend in the diner. Although, within the framework of the oppositional gaze, Beyoncé's character adopts a rebellious stance, refusing to conform to the gaze of desire and possession. Instead, she asserts her power by poisoning her misogynistic boyfriend and evading the police.

Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference”

In Lorde's essay, she states “As women, we must root out internalized patterns of oppression within ourselves if we are to move beyond the most superficial aspects of social change.” (122) One such pattern is internalized misogyny, where women devalue themselves and others, which can lead to judgmental attitudes towards different lifestyles and choices. In "Telephone," Beyoncé exemplifies Lorde's words by not passing judgment on Lady Gaga's choices when she bails her out of jail. Despite their differing lifestyles, they unite against a common oppressor. Furthermore, societal expectations surrounding gender roles can also be internalized forms of oppression, such as conforming to domestic responsibilities. In the video Lady Gaga challenge these norms when she incorporates the stereotype of women in the kitchen within a segment titled “Lets Make a Sandwich”, but instead of adhering to these norms she instead puts poison in all of the food.

Furthermore, Lorde underscores the need to recognize differences among women as equals , relate across the differences, and utilize them to enrich collective visions and struggles. This is shown in the music video through the camaraderie and alliance depicted between Lady Gaga and Beyoncé. The video embraces diversity within feminism, showcasing representations of differences in sexuality and race, yet emphasizing a shared goal of empowerment. This sentiment is also echoed in the lyrics, “Boy, the way you blowin' up my phone , Won't make me leave no faster, Put my coat on faster, Leave my girls no faster”

youtube

"Q.U.E.E.N." by Janelle Monáe ft. Erykah Badu

Janelle Monáe's music video for 'Q.U.E.E.N.,' featuring Erykah Badu, serves as a freedom anthem within a science fiction dystopia. The title itself, 'Q.U.E.E.N.,' is an acronym representing marginalized communities: Queer, Untouchables, Emigrants, Excommunicated, and Negroid, reclaiming royal imagery to challenge traditional hierarchies of race, sexuality, and class. Monáe's Afrofuturist vision suggests a revolution, where marginalized communities and differences are celebrated rather than ostracized. The music video features rebel time-travelers that are frozen in a museum and brought to life by music. In the video's narrative, the song functions as part of a “musical weapons program” that disrupts the status quo, allowing the rebels to move through history and forge a new future in the present.

Laura Mulvey “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”

Mulvey argues that traditional cinematic narratives often reinforce patriarchal ideologies and power structures as they cater to a male gaze. The music video "Q.U.E.E.N." offers a narrative that challenges this as it features strong, empowered female protagonists who challenge traditional gender roles and expectations. Janelle Monáe wears a black-and-white tuxedo, disrupting the traditional notion of gendered clothing styles. The ladies all dance with each other and build eachother up such as when they reply and affirm each other “Is it peculiar that she twerk in the mirror? And am I weird to dance alone late at night? (Nah) And is it true we're all insane? (Yeah) And I just tell 'em, "No we ain't" and get down”. Here, the mention of twerking in the mirror is not sexualized but used to empower the female body.

Bell Hooks, “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators”

The oppositional gaze is seen in the music video as Black female spectators engage with the visual representation of empowerment and resistance depicted in the video. Monáe uses both queerness and Blackness as examples of modern “freakishness.” Monáe doesn't assign a "freaky" status to queerness or Blackness herself, instead, she challenges listeners to interrogate why these identities are perceived as "freaky." She suggests that what society deems as "freaky" is simply the act of being true to oneself. The lyrics declare those differences as things to be proud of stating "Even if it makes others uncomfortable, I will love who I am". Monáe and Erykah Badu illustrate the way society "freakifies" their Blackness, showcasing how joy and celebration within Black culture are often viewed negatively due to racist stereotypes. The hook in the song highlights this, asking: “Am I a freak for dancing around? Am I a freak for getting down? I’m cutting up, don’t cut me down.” Black female spectators can find empowerment in seeing how the song recognizes differences and individuality as prideful assets.

Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference”

Lorde emphasizes the importance of recognizing the intersections of age, race, class, and sex in understanding women's experiences. The video highlights the oppression faced by diverse identities and experiences of Black women, as well as showcases their resilience in the face of it. The lyrics “Add us to equations but they'll never make us equal” resonates with Lorde’s claim that simply incorporating marginalized groups into existing systems does not address the underlying power imbalances or inequalities. Monáe’s next lyrics recognizes these inequalities stating “She who writes the movie owns the script and the sequel, So why ain't the stealing of my rights made illegal? They keep us underground working hard for the greedy, But when it's time pay they turn around and call us needy (needy)” Lorde further advocates for collective action and solidarity among women of different backgrounds to achieve liberation. In "Q.U.E.E.N.," the song's message of female empowerment and solidarity is highlighted as Monáe and Badu come together to celebrate different identities, for example sexual and racial identity. Janelle Monáe promotes unity and collaboration among women as she says “Will you be electric sheep? Electric ladies, will you sleep? Or will you preach?” According to Janelle Monáe it is up to this community and this generation to create its new norm and break down the walls that limit them.

Discussion Questions:

Lorde says ““By and large within the women’s movement today, white women focus upon their oppression as women and ignore differences of race, sexual preference, class and age. There is a pretense to a homogeneity of experience covered by the word sisterhood that does not in fact exist.” In the music video, do you think Lady Gaga is focusing on the oppression of just women in general and treating the experience of all women the same, or is she not necessarily ignoring the differences but the video just does not explicitly address them .

Is trying to make money and bring attention using our bodies promoting sexism even though it is our choice and feel empowering or confidence boosting

In music videos is using Sexuality and promiscuity still catering to the male gaze even if they are active agents in the narrative? What about in the cinema?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text