Venture Capitalist, Board Member, Recovering Entrepreneur, Mom www.heidiroizen.com

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

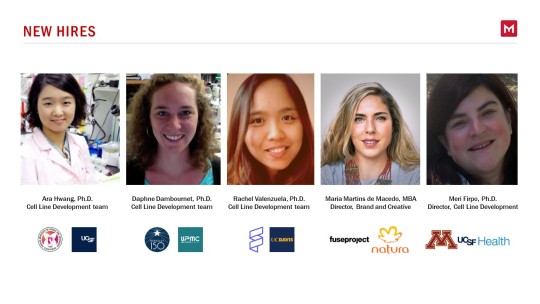

More rare than a Unicorn – gender parity at a venture-backed, deep-tech startup. Here’s how they did it.

One of my most memorable board meetings this year was with Memphis Meats. I literally had to stop the board meeting over one slide, as I had never seen a slide like this in my 20 years as a VC.

And no, it wasn’t about product development or regulatory strategy or burn rate. It was about the company’s newest hires -- five highly accomplished people, all of whom with advanced degrees and significant past achievements in their careers.

And all five were women.

I stopped the CEO, Uma Valeti, right at that moment, to tell him I had never seen a slide like that. And that in turn surprised him, which probably explains in part why Memphis Meats is such a leader when it comes to diversity.

Memphis Meats is a trailblazing company whose mission is to grow real meat from the cells of high quality livestock in a clean, controlled environment. The result is the meat that consumers already know and love, with significant collateral benefits to the planet, to animals and to human health. I’m proud to say they have applied that same trailblazing attitude to growing their team as well.

At Memphis Meats today, 53% of the team are women, and 40% of the company’s leadership positions are held by women. Beyond gender, the team represents 11 nations and 5 continents (Australians, please apply!) and about two-thirds of the team are omnivores, while one-third are vegetarians or vegans. I’ve met most of the team, and I heard all sorts of educational backgrounds: B.S., M.S., M.D., M.B.A., Ph.D. (lots of those). I met parents, brothers, sisters, immigrants, activists, friends, researchers and operators, and I heard 34 different, mission-aligned reasons for joining the company.

Anybody who is paying attention knows that companies and workplaces around the country are grappling with how to build and maintain diverse and inclusive workforces. Silicon Valley is certainly no different – gender imbalance is a well documented problem in tech. Once I saw that slide, I knew I had to dig deeper into what Memphis Meats was doing right. So, I sat down with Megan Pittman, the Director of People Operations at Memphis Meats, to learn more. Here’s what she had to say.

HR: Before we talk about diversity and inclusion at Memphis Meats, we should probably start by defining what we mean when we say those words. What do they mean to you?

MP: We believe that having a diverse and inclusive team happens when you build a culture that’s genuine, welcoming and protected. We don’t have a document that outlines “D&I Policies” here. We didn’t start by looking at our team and saying “wow, there’s a problem here that we need to fix.” We started by committing to build an inclusive company made up of extraordinary individuals. We committed to putting people first, before anything else. We also made the decision to build a People Ops function early, when we only had about 10 employees, so that we could really follow through on these commitments.

HR: I see a lot of companies hire their first HR person when they have 50 or 100 staff. 10 is early! What were some of the changes you were able to make by getting started early?

MP: We’ve curated a high touch and authentic hiring process. After we closed our Series A last summer, we got started on a hiring plan to grow from 10 to about 40 people, and we wanted to do it in about a year. We began recruiting and interviewing immediately!

Pretty quickly, we realized that our interview process wasn’t working very well. We were spending a lot of time with candidates who had amazing resumes, but we weren’t developing unanimous conviction around who to hire. We weren’t being blown away. So we stopped interviewing for a bit and started debugging. We realized that our interviews were too formulaic, and too focused on checking boxes on the job description. We were talking to people who had already accomplished amazing things – in industry or academia, or both – and we weren’t letting them tell that story. So we couldn’t assess their accomplishments, their ambitions and their ability to innovate. We could only assess their resume, and maybe their small talk skills.

We decided to rebuild the process to let the candidates shine. Now, we ask all prospective hires to start their interview day by giving a ~30 minute talk to our team, typically focused on their greatest accomplishments or a topic that they know extremely well. The talks are a great way to see a candidate at his or her best. They provide great context for the 1-on-1 interviews later in the day. And our team learns something new every time a candidate comes in. There have been some pretty amazing light bulb moments and inspiring conversations that have originated because of these talks. Our team loves them – they’re always a hot ticket in our office!

HR: How do the talks connect back to diversity and inclusion?

MP: The talks let us have a really relevant, organic conversation and put the candidate’s resume to the side for a moment. After the talk, we can ask the candidate how they could have done that better, or faster, or cheaper. We can hone in on moments where they did something creative, and learn about their thought process or problem solving strategies. We can hone in on roadblocks, and understand how they motivate themselves through the most difficult moments.

We’ve seen plenty of data showing that companies that hire based on resumes and checkboxes end up with homogenous workforces. Don’t get me wrong – great resumes and hard skills are requirements at Memphis Meats, but they’re the price of admission and not the focus of our hiring process. When we go beyond the resume, and let the candidate shine, and expand the hiring criteria to include self-awareness and creativity and tenacity, we see a very diverse group of people rise to the top. And they happen to be the exact people that we need.

Now that we’ve been doing this for a while, we’re also getting better at writing job descriptions. Our hiring managers now ask “what do we need our next person to bring that our team doesn’t already have?” There is a quote by Walter Lippman, an American writer, that speaks to the importance of this. He says, “When all think alike, then no one is thinking.” Our team is sold on the value of new perspectives, and we’re now thinking about it before we even start to meet candidates. It’s a virtuous cycle.

HR: What happens after the hiring process? Great, you’ve found the person – now what?

MP: We’ve put a number of tools in place to ensure that we can close great candidates and get them into their new role here. For example, mobility platforms have enabled us to not be limited to hiring scientists, engineer or operators in the immediate Bay Area. We are able to comfortably source individuals from top companies or labs – whereverthey are. Switzerland? No problem. Canada? Great! Minnesota? Easy. We offer professionally managed relocations so that we can pull talent from a much bigger pool.

We have partnered with a top immigration attorney so that we can support any qualified individual in obtaining employment eligibility. We have worked with hires on multiple visa applications but one sticks out. We interviewed an incredible scientist who is a French citizen. She is so smart, so hard-working, and so talented. For a few reasons, we realized we would only be able to hire her on an O-1 visa, which is reserved for individuals with “extraordinary ability.” The bar is high, and nobody is a sure thing to get this type of visa. We spent months working on the application, and demonstrating her accomplishments as thoroughly and accurately as possible. After more months of waiting, we literally received her visa approval hours before her previous employment eligibility expired. The entire Memphis Meats team celebrated. The room started cheering, we high-fived, we picked up a cake, I probably cried. She has since been named on our most recent patent filing and has contributed in so many measurable and immeasurable ways to our team. She was absolutely the right person to hire and we did everything we could to make it happen.

We diligently pay fair to market wages and make offers that are not based on salary history. We have never requested salary history from our new hires. We prefer to base all offers on the market, our fundraising stage, precedent in the company and level of experience. Period. We take every offer very seriously and will continue to make that commitment to every one of our team members.

We constantly solicit feedback on our processes and look at data. We track the source of our hires: are we relying too much on one company or one local university lab? We track the candidate experience: are candidates feeling respected by us, our process and our timelines? We track our internal rates of diversity. All of this works to discourage complacency in our processes, and ensure that we are constantly aiming to be better.

We took a different approach to benefits compared to many other venture backed companies. We don’t invest our money into dry cleaning and massages and abundant free meals. Instead, we’ve invested in a generous paid family leave policy, and great health care, and a floating holiday policy that allows for religious or cultural differences. People need to be able to live their lives how they choose with a job that supports that without question. We ask a lot of team members so it’s our responsibility to support them in their lifestyle choices.

HR: Many companies start with the best intentions, and compromise those as they grow. How do you imagine Memphis Meats staying the course?

MP: We’ve really made inclusiveness part of our identity. This goes way beyond a D&I policy, which can be easily forgotten or lost in a handbook.

We talk a lot about our “big tent,” which is really a cornerstone of our company. We’re making meat in a better way. You might think we’re out to “disrupt” an incumbent industry or to make consumers feel guilty about what they’re eating today, but the opposite is true. We recognize and respect the role that meat plays in our cultures and traditions. Many members of our team eat meat, and we celebrate that. Many members of our team do not eat meat, and we celebrate that. There’s just no place here for moral judgment.

Over time, that philosophy expanded to cover the companies and organizations we work with, the investors we raised money from, and the language we use. We happily work with large meat companies like Tyson and Cargill. We happily work with mission-driven organizations that work for animal welfare or environmental stewardship. We happily talk to consumers of all stripes. We’ve built a coalition that we never would have expected. We’ve found that everyone we talk to unites behind our goal of feeding a growing and hungry planet. Our internal culture and our people processes are consistent with the idea of the “big tent,” so I don’t think they’re going anywhere.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s no longer ‘where’s the beef’, it’s ‘what’s the beef’ – and what happens next could have a chilling effect on the innovation desperately needed to dramatically improve how meat is produced.

The US Cattlemen’s Association has a beef with me.

Well, not me exactly, but with a company DFJ has invested in (and on whose board I serve), Memphis Meats, and other companies like it, who are trying to add new choices to the way our favorite proteins are produced.

In a recent petition submitted by the US Cattlemen’s Association (USCA), a trade association that aims to support the interests of livestock producers, the Cattlemen have asked the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to restrict the definition of meat to mean only ‘meat from a slaughtered animal’. The Cattlemen’s petition is currently under review by the USDA, and if the request were to be accepted, it would end the ability for companies like Memphis Meats to call our meat products, well, meat.

That seems pretty crazy to me, especially in the case of Memphis Meats. You see, Memphis Meats is a food company that produces meat and poultry from animal cells. With a diverse group of supporters and investors including DFJ, Tyson Foods, Cargill and Bill Gates, Memphis Meats intends to work alongside conventional animal agriculture to produce meat and poultry in a safe and scalable way. I think the fact that two of the largest entities in the meat industry have also made investments in Memphis Meats speaks to the important nature of the work being undertaken at Memphis Meats.

Many leading industry experts have pointed out that the current methods of production create huge issues for our environment. The method of ‘growing meat’ through live animals is also very inefficient, in fact here’s a fun fact for you – it takes about 23 calories of input to create a single calorie of beef, and after all that feeding, less than one-third of the cow is actually edible meat. Much of the cow’s carcass is not even eaten. Today’s methods also use huge amounts of the world’s arable land, fresh water and energy. We are facing a rapid growth in the global demand for meat. If we want the world to keep eating meat -- and that is clearly something humans seem to want to do -- it is imperative for us to use innovation and explore new ideas.

Memphis Meats sees itself as a member of the food and agriculture community, and we must all work together to make the food system better. The company is committed to being honest and transparent with both regulators and consumers about its products and how they are made in an ongoing effort to build trust. We strongly believe that clean/cultured meat will be an important way to produce meat and poultry products, alongside conventional practices, in a manner that is safe, scalable, and sustainable. We all want to help meet the overall global demand for meat products and we are happy to live by rules that will help consumers feel great about the safety of what’s on their plates.

But let me be clear. We are making meat. Literally. What the heck else would we even call it?

To paraphrase the duck test– if it looks like duck meat, tastes like duck meat, was grown from duck cells, is cellularly identical to duck meat, and has the same functional, compositional, and nutritional characteristics of duck meat, it is duck meat!

I am one of the few lucky people who have already tasted Memphis Meats duck (sautéed with nothing other than salt, pepper and oil, by the way) and let me assure you, it is fabulous and completely indistinguishable, at least to my taste buds, from any duck I’ve eaten before.

Thinking even bigger for a second: The U.S. Cattlemen’s Association’s petition, if granted, would stifle innovation in meat and poultry production such that no method of development other than “traditional” or current practice could be used to produce meat and poultry products, regardless of the safety, composition, function, and other characteristics of the finished product or its labeling. Chilling important advances in food production without justified reason would encourage a technological standstill at a time when the global need for protein-based foods is on an exponential rise. The US agricultural industry has been the world’s best model for food innovations that produce delicious, nutritious, and safe foods for our families. Memphis Meats is helping to preserve this tradition of innovation in the US by bringing meat to the table using new production methods.

Do you think other countries are going to similarly stand still when faced with the growing desire and need for meat? I certainly don’t.

Memphis Meats has submitted comments requesting that the U.S. Department of Agriculture deny the Petition by the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association. Instead, we think the USDA should collaborate with stakeholders across the industry and at the Food and Drug Administration to develop a modern regulatory framework that supports innovation and the continued growth of the meat and poultry industries.

If anyone reading this would like to voice an opinion, feel free to submit your comment to the USDA here. The deadline to voice your opinion on this important issue is midnight Eastern Time on May 17th, 2018.

It is an honor to work with the wonderful people at Memphis Meats and I look forward to the day everyone can try our meat!

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been speaking about leading a relationship-driven life of late, so thought I would repost this as a good summary of my advice. Enjoy!

The magic question that turns transactions into relationships

I’ve been talking a lot lately about being relationship-oriented as opposed to transaction-oriented (for example here and here. )

In short, I believe that many good things – personally and professionally – come from putting relationships ahead of any individual transaction.

I also believe that the process of conducting a transaction is a powerful opportunity to build a relationship. Why? Because a transaction is an opportunity to create an outcome that someone else cares about. Create a better outcome, and the person on the other side will appreciate that, and think of you positively for future transactions as well (usually a good thing.)

But how do you do that in practice?

The first important step is to go into any negotiation with the right mindset. Stanford Professor Richard Pascale said it best in a class I took when I was in business school:

Negotiation is the process of finding the maximal intersection of mutual need.

This to me is a very powerful construct. Negotiation is not about getting the most of what I want. The best negotiations (transactions) leave us both better off.

However, in my many years of practicing this mindset, I’ve found there is often a roadblock to finding these maximal intersections of mutual need. And it is a surprising one:

People tend to ask for what they want.

While that sounds like a very reasonable thing to do, it doesn’t lead to the best outcome for either of us.

Here’s why.

Generally, you conduct transactions because you are trying to solve a problem. Let’s say, for example, your child has just hit school age and you and your spouse determine that you need to send him or her to an expensive private school because of a learning disability. You have a problem though – you don’t have enough current income to make ends meet with this new school. So you come to me, your boss, and ask me for a raise. I, your boss, have my own problems. I want to make you happy, but I can’t pay you above what everyone else makes just because you need it more. So I say no. Problem not solved.

What you missed out on, by asking me for what you wanted, is that you missed the opportunity for me to help you solve your problem – which is what you really want.

This is generally what people do. They ‘solve’ their problems using only their brain, considering only the options they know to be available. And by doing so, they miss the opportunity of applying someone else’s brain – a brain with other assets and other knowledge about available solutions – to the task.

Let’s replay the above problem. Same situation, but now you come to me, your boss, and you say, “I have a problem. My kid needs to go to private school because of a learning disability and I can’t afford it.” Maybe I can’t give you a raise, but maybe I know of a scholarship or support program that may be available to you, maybe I know of a new school starting up with lower tuition, maybe I’ve had experience with a great public school with a special program that you can apply to transfer to. Maybe I know someone with a child older than yours, who went through the same issues and found a great solution, someone I can introduce you to who in turn might have a great solution to your problem. The point is, maybe I can help solve your problem without paying you more money.

In short, the problem with people asking for what they need, is they used only their brain to figure out what they need. It is far more powerful to also use the brain of the person on the other side of the table.

So, next time you are in a negotiation, instead of stating what you (think you) need, or even asking the other party what they (think they) need, instead ask this:

“What problem are you trying to solve?”

From my experience, this question is literally magical when used in a negotiation.

First of all, it takes the focus off what I want. Even though I have my own problems in the back of my head, right now I will focus on you, which makes you feel really good about me just for doing it. My credibility goes up with you.

Then, I have the opportunity to apply what I know, who I know, and what I have, to solving your problem. And as I’ve often found, the things I have that you don’t know about can create a superior solution for you that also works better for me.

When I then lay out for you what problem I am trying to solve, a similar thing happens. There is a powerful, subtle shift that occurs when we move from you-versus-me to let’s-work-on-our-problems together. We build a relationship above and beyond what we are working on right now, and we develop a pattern of communication and a level of trust that will make anything we do together in the future easier.

I have countless examples of how this has worked for me, but rather than tell you mine, I’d suggest instead you simply go try it for yourself.

What have you got to lose, except for a few problems you are trying to solve?

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

So proud of my partner Emily Melton for the work she is doing to bring more gender parity to the venture capital industry.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

DFJ in the news...

As many of you know, in the past few days DFJ has been rocked by allegations about sexual harassment. I’d like to be fully transparent about what we know and what we are doing about it. In our entire history, DFJ has never received an official complaint alleging misconduct by anyone on our team. That said, during the summer this year, we heard about allegations of misconduct by one (and only one) of our partners from a third party. We felt the responsible thing to do was to launch an independent investigation, and so we did. It is still ongoing. In the past week, a single Facebook post also accused DFJ of having a culture that is predatory to women. I don’t need an investigation to state with certainty that this is patently wrong. I am too grizzled and old to write bullshit about a company to please my boss. I’m writing this because I believe it to be true. I value my own personal reputation and integrity above any firm, and simply put, I would not work for DFJ if I felt the culture was not one of high integrity and opportunity for all — including women. Including me. I am honored to work with a fantastic team of investment professionals and executives, many of whom are women. If you want to hear directly from us about what it’s like to work here as women in VC, feel free to email us.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Entrepreneurs: Please Stop Shooting Yourselves in the Foot.

I was going to start this post with a few links to recent events, but frankly there are so many it is dizzying to do so. So, I am going to presume if you are reading my blog you are at least a little familiar with what is going on at Uber, including today’s resignation of board member David Bonderman.

Sadly, I see this stuff in startups all the time -- unprofessional, juvenile actions and communications initiated by the senior leadership or founders and justified under the guise of ‘we like an edgy culture’ or ‘we were just being funny’ or something like that.

To all of you I’d like to suggest something: Grow up.

Here’s the thing. All your stakeholders want you to win. Your investors provided capital (often with limited control) because of a belief in you and what you are trying to do. Your employees choose to come to work for you every day, over other things they could be doing, presumably because they also believe in that mission.

And you know what is true about your mission? It is really, really hard to actually accomplish it. You are constantly trying to do the impossible, to create products and services that haven’t existed before. You face ridiculous timelines, incredible competitive pressure, difficult decisions that don’t have consensus, challenges with hiring and retaining your people, and of course the looming pressure of continuing to raise capital to lengthen your runway, all in the service of this mission that you deeply believe in.

With all the challenges you face, why do you need to self-inflict more?

Entrepreneurs I have worked with who have found themselves on the wrong side of these issues usually defend themselves with either the ‘culture’ argument or the ‘its my personality’ argument (and of course those two are deeply intertwined.)

To that I ask, is it worth risking your mission? Wouldn’t it be better to understand that these sorts of behaviors do more harm than good? Can’t you create a great culture without resorting to frat bro humor? Don’t all these recent events indicate that perhaps these actions are simply not worth the downside?

I’ve written about culture before, but to summarize, culture is about actions and it almost always is created (whether they understand they are doing so or not) by the founders. If you want my advice, you should build the culture that will best serve your mission – one of integrity, excellence, performance, and delivery of the dream. Anything that diminishes this is shooting yourself in the foot.

Isn’t what you are doing hard enough already?

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering my Dad, and thanking the America that let him in.

My Dad, Joseph Roizen, died 28 years ago today. There’s barely a day that goes by that I don’t think of him.

He entered America by way of Canada in 1951, an energetic young man of Russian Jewish heritage, born in Kishinev, Romania. He was equipped with a hodge-podge of unfinished education between high school and a little college, and had in tow a wife and two young sons. He had no money, but he had unbounded energy and a deep belief in the American dream, which he shared with me countless times in the years that followed through his words and actions.

My parents eventually settled in Palo Alto, California, and my Dad got a job at Ampex. I think of him every time I drive by the sign on 101, which still stands although the company is no longer there. For those interested in why see here.

I was born shortly before he was sent by Ampex to the USSR for a technology exhibit, during which he stood behind the video camera as the infamous Kitchen Debate unfolded, capturing it on the then-new color videotape technology he had helped to invent. The Ampex team’s recording, which was smuggled back to the US, earned Dad not only an Emmy Citation, but also the personal pride that he had helped America in its fight against the Soviets.

Dad used to say to me “honey, you never need to leave the Bay Area, because I have searched the whole world over and there is no better place to be, for lifestyle and for work, than here.”

I cannot imagine what life I would have had, had they chosen somewhere else to settle. I’m grateful not only for his choice of location, but for his never-ending encouragement to me to pursue a great education, do whatever I wanted to do, and figure out a way to ‘not have a boss’ -- a lifetime goal of his and one I fulfilled for myself when my brother Peter and I started T/Maker in the early ‘80s.

And I am deeply grateful – especially at this time in history – to the America that let in a Russian/Romanian Jew with little education and no money to pursue the American dream.

My brother Ron wrote and presented this biography of my Dad at Dad’s memorial service, I’m quoting directly for much of the history that now follows. The original is even better, so if this story engages you, please visit the full work here.

We miss you, Dad.

From my brother Ron:

Thoreau said that most men lead lives of quiet desperation. That was not my Dad. Joe Roizen was a great lover of life, exuberant, enterprising, boundlessly energetic, responsible, passionate, optimistic and, when it was needed, even brave.

Joe was born in 1923 in Kishinev, Romania — in the turbulent wake of the Russian Revolution. His father, Boris, and his mother, Brana, had only six months previously escaped from Russia. Brana gave birth to Joe while waiting for her husband’s release from a Romanian jail.

The story of the escape and passage to North America was one of family ties and help. My father made the long sea voyage at age three months — already a world traveler, the fare being paid by an uncle who had already made it to the new world.

The family first went to Halifax, then Toronto, and finally ended up in St. Agathe, a resort town in the Laurentian Mountains and the location of a Jewish sanitarium that treated Joe’s father for T.B. Boris died when my father was twelve, in 1935. My father was left fatherless at this tender age and in the depths of the great depression. This hard reality surely galvanized his lifelong willingness to embrace responsibility and work hard.

Joe was a good student, but by the middle of the 10th grade financial straits obliged Joe to quit school and work full-time, coat-basting. Thereafter, he managed to attend night school and took classes at Sir George Williams College.

With the war’s outbreak in 1939, my father (now 17) tried to lie about his age and join the Royal Canadian Air Force. He didn’t succeed, but he did become the rear-seater radioman in testing Helldiver carrier fighterbombers at Fairchild.

Joe married my mother, Gisela ‘Doris’ Holl, in 1943, and I (Ron) was born when Joe was only two weeks past his own 20th birthday.

Joe was an entrepreneur at heart. Immediately after the war, he started two companies with Charlie Rosen and Solly Mann — Electrolabs, which started out making a diagnostic instrument for auto garages and ended up making intercoms, and Amplitrol, which made a pretty sophisticated bank alarm for its day. Neither made enough money in the early years — and so my father was forced to abandon them soon after their founding — but both survived and Amplitrol was ultimate acquired by Honeywell.

According to Charlie, an incident prompted Joe’s and his abandonment of Amplitrol. A big — even crucial — customer demanded a kickback for the next year’s purchases. They told him to take a walk — and began looking for other fields of opportunity. As Charlie noted, even as a very young man with no capital and no safety net, Joe had the energy and the guts to venture out on his own.

My brother, Peter, came along in 1946. Joe next worked at Trans-Canada Airlines, again in radio. As a perk, he got free air passes for vacation journeys. In 1948, Joe and Doris visited L.A. They even got on the Gary Moore radio show and won a multi-course dinner at Graumann’s Chinese Restaurant in Hollywood. What impressed them most was the weather. They had left Montreal in snow and found L.A. in summer warmth. They decided to move — with no waiting job, no house, no particular prospects save for Joe’s sense of energy, self-worth and employability, and of course, with no US citizenship. This was classic Joe — move, and then use your wits and energy to make things work.

Joe’s first L.A. job was with Pacific Mercury, which made TV sets for Sears; next he worked for KTLA, where he learned color TV technology first-hand. He always worked evenings in the garage to earn a little extra for the things he and our family enjoyed.

My dad and mom loved to pack up the car and see the sights — Yosemite, Sequoia National Park, Victoria, B.C. Trips also exercised his lifelong love of photography. On one such trip in 1951 they discovered Lake Tahoe. They bought a quarter-acre lot with a terrific view, and my father had to rush home to repair a couple of TV sets in their garage in order to cover the down-payment check.

They fell in love with Tahoe. In summertime, Joe asked for extra unpaid vacation, but was denied. So, he simply quit his job every June and won it back again every September.

The wearingly long L.A.-Tahoe drives caused them to look for a home closer to the lake. In 1956, the family moved to Palo Alto; Joe began work at Ampex. Baby sister Heidi came along a few years later, the first in our family born in America.

Joe made many contributions at Ampex, and Ampex was the place that allowed his technical creativity to blossom and also provided a worldwide set of colleagues that he later relied upon to start his own business to fulfill his life-long dream of “not working for somebody else”.

My Dad and Mom split at this time and there were some lean years when his first company didn’t work out. However, he rebuilt his life, remarried happily (to Donna Foster Roizen, who was with him until his death) and created a small consultancy in the video field that afforded him 250k miles a year of travel all around the world, the opportunity to choose only clients he liked and projects he found interesting, and plenty of opportunity to tell jokes, host home-cooked dinners at his Portola Valley house, and take pictures. He had arrived at a nearly ideal circumstance, and he knew it, and he relished it greatly.

A letter he wrote me (Ron) — when I was going through some troubles — expressed something of the feeling. He wrote:

With a 20 year lead on you, I can only say that you are still a young man with the best years of your life still ahead. There is an inner satisfaction from middle age, which comes from having lived long enough to define who and what your are, and what you want to do with that. I thought I reached that point when I was 35, and I felt I could bear whatever life threw my way after that.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Startups: Here’s How to Stay Alive

There are storm clouds gathering over Silicon Valley -- and it’s more than just El Nino.

As a venture capitalist, I see a lot of data points within the private company marketplace. Every Monday, I sit in a room with my partners and we discuss dozens of companies, both portfolio companies as well as those we are considering for investment. When a market turns, we tend to see the signs earlier than the entrepreneurs working on the front lines.

This market? I’d say it has turned.

It is going to be hard (or impossible) for many of today’s startups to raise funds. And I think it will get worse before it gets better. But, hey, my entrepreneurial friend, who ever said it was going to be easy? One of my favorite expressions is: “that which does not kill us makes us stronger.”

So which is it going to be for you? Tougher? Or dead.

Fortunately, (unfortunately?) I’ve been to this movie before, during the dot-com “nuclear winter” – anyone remember that? I’d like to think I’ve learned some things from that painful experience.

I’ve seen companies live, and I’ve seen them die. And I’ve concluded that certain behaviors separate the two.

Which behaviors, you ask? Here are a few from my downturn playbook for how to stay alive.

Stop clinging to your (or anyone else’s) valuation: You know what somebody else’s fundraise metrics are to you? Irrelevant. You know what your own last round post was? Irrelevant. Yes, I know, not legally, because of those pesky rights and preferences. But emotionally, trust me, it is irrelevant now. We even have a name for this – valuation nostalgia. Yes, it was great when companies could raise those amounts, at those prices, blah, blah, blah, but the cheap-money-for-no-dilution thing is largely over now. The sooner you get on with dealing with that, and not clinging to the past, the better off you will be. As my DFJ partner Josh Stein says, “flat is the new up.”

Redefine what success looks like: I had lunch last week with a friend of mine who broke her leg in three places four months ago. “I used to think a successful weekend was 10+ miles of running,” she said. “For now, success is going to have to mean making it to the mailbox and back without my crutches.” When a market like this turns, in order to survive, it is critical to redefine what success is going to look like for you -- and your employees, and your investors, and your other stakeholders. Holding on to ‘old’ ideas about IPO dates, large exits and massive new up rounds can ultimately be demotivating to your team. If you can make it through the downturn, you will have those opportunities again. But for now, reset your goals.

Get to cash-flow positive on the capital you already have (AKA, survive): My DFJ partner Emily Melton said this in our last partner meeting: “Must be present to win.” I used to say it at T/Maker (the company for which I was CEO) in a slightly different way: “In order to have a bright long-term future, we need to have a series of survivable short term futures.” You need to survive in order to ultimately win.

You know what kind of companies generally survive? Companies that make more money than they spend. I know, duh, right? If you make more than you spend, you get to stay alive for a long time. If you don’t, you have to get money from someone else to keep going. And, as I just said, that’s going to be way harder now. I’m embarrassed writing this because it is so flipping simple, yet it is amazing to me how many entrepreneurs are still talking about their plans to the next round. What if there is no next round? Don’t you still want to survive?

Yes, some companies are ‘moon shots’ (DFJ has a fair number of those in our portfolio) where this is simply not possible. But for the vast majority of startups, this should be possible.

So, for those of you in the latter group, I want you to sharpen your spreadsheet, right now, and see if, by any hugely painful series of actions, you could actually be a company that makes money. ASAP. Or at least before you run out of money. Because that’s the only way I know to control your own destiny. You don’t have to act on it (although I would), but at least you will know if you have a choice.

And if you absolutely, positively, cannot get there without more capital? Then you need to…

Understand whether your current investors are going to get you there: Guess who else cares about whether you live or die? Yep, your current investors. Another duh. That’s why they are your best source of ‘get me to cash flow positive’ financing. And yet, even though we all know this, why is it we don’t actually (1) create the plan that gets us to cash flow positive ASAP, and then (2) go to our backers and get their commitment that they will see us through (or know that they won’t, because if they won’t, the sooner we know that, the sooner we can go out and do something about this.) I know many VCs hate to be put on the spot about this, but I think entrepreneurs have the right to ask, and to know.

Stop worrying about morale: Yes, you heard me right. I can’t tell you how many board meetings I’ve been in where the CEO is anguished over the impacts on morale that cost cutting or layoffs will bring about.

You know what hurts morale even more than cost- cutting and layoffs? Going out of business.

I was at a conference once where someone asked Billy Beane how he created great morale at the A’s. His answer? “I win. When we win, morale is good. When we lose, morale is bad.”

Your employees are smart. They know we are in uncertain times. They see the stress on your face. They worry about their jobs. What do they want to see most? A decisive plan for survival, that’s what – even if some of them have to go. Trust me, a clear plan is a real morale turn-on.

Cut more than you think is needed: Yes, this is simple, but not easy. It is so easy to justify why you want to lay off fewer people. However, when you do, by and large, you’ll be laying even more off later. Why we humans seem to prefer death by a thousand cuts is a mystery to me. Don’t. It’s easier on everyone if you cut deeper and then give people clarity about the stability of the remaining bunch.

Scrub your revenues: Last week an entrepreneur pitched us, and his ‘current customers’ slide was alight with bright, trendy logos of bright, trendy venture-backed companies. You know what I saw? A slide full of bright, trendy, money-losing, may-not-survive companies. (Luckily, in this case, the entrepreneur referenced these customers because he thought VCs would like to see that their smart startups use his stuff, but he actually had a lot of mainstream customers too. He has a new slide now.) This, I think, was one of the biggest surprises from the last dot-com bust -- we all knew we had to cut our expenses, but no one thought about what our customers might be doing. And guess what? They were all cutting costs too – including those costs which comprised our revenues. Or worse, they were going out of business. If you are in Silicon Valley and your customers are mostly well-paid consumers with no free time, or other venture-backed startups, well, I’d be worried. And yes, it sucks, but it is better to be worried than surprised.

Focus maniacally on your metrics: I know a few CEOs who delegate the understanding of their financials and their business metrics to the CFO, and then stop worrying about all that ‘numbers stuff’. Don’t do that. You have to know your numbers inside and out -- they are your life blood. You also have to know which metrics drive the business, and focus on them like your survival depends on it – because it does. Figure out your canary (or canaries) in the coal mine (by that I mean the leading indicators that tell where your business is headed and whether it is healthy) and watch them weekly, or daily, or in real time, whatever is possible. And, have a plan in advance about what you will do if/when the metrics go south. Many of the best companies to have survived the last downturn became super data-driven, and were constantly course-correcting to make small but continuous improvements in their operations with what they learned.

Hunker down: These markets generally take a long time to recover. Longer than you think. And, it might get worse. So don’t plan for the sun to start shining tomorrow. Or next month. Or next quarter. Or maybe even next year. Sorry.

Having just thoroughly depressed you, let me say that I’ve seen amazing transformations by companies who adapt early to the new reality. Severe budgets give clarity. Smaller teams often find greater purpose in their work. Gaining control (by becoming profitable) feels really, really good. Watching your competition (who didn’t read this) die, feels – can I say it? – well let’s just say that when your competition goes out of business, you often gain their customers...and that’s a very, very good thing.

Some of the greatest companies were forged in the worst of times. May you be one of them.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Build a Unicorn From Scratch – and Walk Away with Nothing.

This is a grim fairy tale about a mythical company and its mythical founder. While I concocted this story, I did so by drawing upon my sixteen years of experience as a venture capitalist, plus the fourteen years I spent before that as an entrepreneur. I’m going to use some pretty simple math and some pretty basic terms to create a really awful situation in the hopes that entrepreneurs reading this might avoid doing the same in the real world.

As I’ve seen over many years and many deals, in all but the most glorious outcomes, terms will matter way more than valuations, and way more than whatever your cap table says. And yet entrepreneurs – often with the encouragement of their stakeholders – optimize for the wrong things when they negotiate their financings.

This is my attempt to paint you a picture of why this is such a bad idea. The situation I present is fake, but the outcome is remarkably similar to those I’ve witnessed. Don’t let this happen to you.

Let’s start with our entrepreneur, whom we’ll call Richard. He’s founded a breakthrough company. Let’s call it Pied Piper.

Richard attracts Peter, a newly-wealthy budding angel investor, who agrees to put in $1 million as a note with a $5 million cap and a 20% discount.

With his $1 million, Richard builds a small team of people, rents an Eichler in Palo Alto, and gets to work. Once he is able to demonstrate his product, he heads to Sand Hill Road. He’s in a hot space in a hot market. He nails his pitch, and the term sheets roll in.

Because Richard is extremely sensitive to dilution (after all, he’s seen The Social Network) he wants the highest valuation possible. (Early in my career, another venture capitalist called valuation ‘the grade at the top of the paper’ -- and I’ve never forgotten that.) The highest valuation, $40 million pre-money, comes from an emerging venture fund, let’s call them BreakThroughVest (BTV). BTV is excited about this deal, but has ‘ownership requirements’ of at least 20%, so they insist that to support that valuation they need to invest $10 million. Plus, they want a senior liquidity preference of 1x to protect their downside since they feel the valuation is rich given the stage of the company.

Richard is thrilled with the valuation and the fresh capital for only 20% dilution. The prior investor, Peter, is stoked that he is getting his $1 million investment converted into roughly 20% of this super hot company, and now with the validation of an external term sheet he can mark his position up to $10 million, a 10X! This helps Peter validate his position as a savvy angel and solidify his syndicate following on AngelList.

Term sheet signed. Champagne popped. A few weeks later, funds wired.

With the $10 million, Richard rents space in SoMa on a seven-year lease, hires lots more people, and within a few months he is able to roll out the minimally viable product to test the market. Awash in the buzz of his fundraise, a feature in Re/code, and some early user traction, Pied Piper is perceived as the emerging leader in a nascent, winner-take-all market. While they are not yet monetizing their users, the adoption metrics are off the charts.

Pied Piper attracts the attention of a tech giant we’ll just call Hooli. Hooli’s consumer group wants access to Pied Piper’s data. With Hooli dollars behind Pied Piper, Pied Piper could inundate the market with consumer facing advertising to build their user base and upend competitors given the massive network effect of the product. Hooli approaches Richard with the idea of a large strategic round. In the deal, Hooli would invest $200 million for equity while in return the two companies would enter into a business development agreement on the side in which Pied Piper guarantees to spend that money in a massive consumer campaign on Hooli’s ad platform. They float the magic “B” valuation. Richard goes to sleep dreaming of rainbows and unicorns.

Richard fantasizes about being named a member of the Unicorn Club by the press. His employees calculate the huge paper gains on their options -- they will all be instant millionaires -- and since no one is more than ¼ vested, they are all highly motivated to stay in spite of long, long work hours. BTV is thrilled with the 20x markup on Pied Piper, since they are about to hit their LPs up for a new fund. The original investor, Peter, has achieved legendary status – his $1 million has turned into approximately $200 million on paper. He’s on the YC VIP sneak preview list, he’s been offered a spot on Shark Tank, and Ashton just called to try to get into his next deal.

Of course, that $200 million for 20% stake also comes in with a senior 1x liquidation preference in order for Hooli to create sufficient downside protection and thereby justify the $1 billion valuation to their board.

Richard, Peter and BTV all agree it is worth doing. With $200 million to spend on the most massive consumer-facing ad campaign in this sector’s history, the $1 billion valuation will seem low in retrospect.

Except, it doesn’t end up happening that way.

The ads start running, but the conversion rate is low. Pied Piper shows Hooli the atrocious metrics and demands out of the advertising commitment, but Hooli won’t budge: Performance metrics were not pre-negotiated, and furthermore the ad group that recommended the investment did so in part to prop up their revenues with Pied Piper’s money ‘round-tripping’ into their coffers. The ad group is counting on that money to hit their annual numbers.

Pied Piper is forced to run the whole campaign, blowing through all $200 million. The good news: They increased their user base by 10x. The bad news: The resulting business model those users end up actually supporting equates to more of a ‘market valuation’ of $200 million. In more bad news, turns out Richard incorrectly estimated the cost of supporting those users, most of whom are taking advantage of the ‘free’ part of a freemium model. Support costs skyrocket.

Word about the poor conversion leaks out. The advertising stops when the money runs out. Growth slows to a trickle when the advertising stops. New investors sniff around, but with the preference overhang of $211 million, they are concerned about employees being buried under that structure and therefore being unmotivated to continue. They ask prior investors to recap, but the investors don’t want to give up their preferences: Pied Piper is now looking like it might be worth far less than the paper valuation, which means those preferences are very valuable as downside protection. Furthermore, BTV is out raising their fund, and the last thing they want to do is write down their 10x markup on the Pied Piper investment.

The board is now super unhappy about the massive miscalculation of support costs, awful user conversion, gargantuan ad overspend, the lack of growth the company is experiencing, and the departure of a few key employees who’ve seen this movie before and have done the ‘overhang math’. Richard as CEO is out of his element -- the problems are huge and the company needs more money, which he is incapable of raising given his lack of experience navigating waters like these. Unfortunately, it is the CEO’s job to fix problems and raise money, and if he can’t do it, someone else has to. So the board (which now controls the company with 60% of the stock) votes to remove Richard as CEO. They recruit an interim CEO (let’s call him George) to quickly take the helm. George says he’ll take the job on two conditions: One, that they create a 5% carve-out for him and the go-forward employees (he’s done the overhang math too) and two, that they extend the runway so he has time to either turn this thing around -- or sell it.

The company is not profitable and the current investors are tapped out. “Let’s extend the runway using debt,” says BTV. Maybe things will improve with time – or at least perhaps they can get their fund closed before they have to take the write down.

They lean on their good friends at PierLast Venture Bank who cough up $15 million in debt, with a senior preference and a 2x guarantee. Onerous terms to be sure, but hard to get debt with a balance sheet like this. Unfortunately, Pied Piper is burning $2 million a month on office space, cloud services, customer support, and expensive employees who are needed to build the next generation of the product. Without support they’d have to shut down existing customers and revenue, yet without development of the new release that they hope will save the company, they will have nothing to sell. Since they can’t cut their way to glory, they have to simply hope they can grow into their valuation.

Time ticks by while the company plods forward with very slow growth. Market pressures force them to lower prices, pushing profitability off. A few key developers leave. Once again, they are facing the prospect of running out of money in 90 days. Current investors are worried. Not only do they not have funds to put into the deal, but once payroll is missed they could be personally liable for the damage. Not good.

Luckily, WhiteKnight, a public company with a complementary product and plenty of cash, offers to buy Pied Piper. The offer is $250 million. It’s not a billion -- but it’s still a big, impressive number. It’s not that easy to create a company worth a quarter billion real dollars to someone else. That’s huge!

The venture debt provider PierLast is very nervous about Pied Piper’s balance sheet and looks to the VCs to either guarantee the loan or get the sale done. They want their $30 million. Hooli is likewise pushing to sell, after all they are guaranteed the first $200 million of any proceeds, after repayment of 2x debt to PierLast, while the company would have to be worth over a billion for them to see any further upside given that they only own 20%. Their calculus is that this is about as unlikely as seeing a real unicorn given the state of the company. BTV, who no longer has any capital left to invest from their original fund, has recently closed their shiny new $300 million fund, so they decide it is time to take their chips off the table. They vote to sell too, getting their $10 million back. Peter, while sad about the outcome, has developed a huge syndication following on AngelList and has recently benefitted from an early acquisition that netted him $3 million on a $250k investment. Can’t win them all, but he’s at peace. Even Richard votes yes to the sale: He still has a board seat but given the company’s lack of profitability and lack of any other sources of capital, turning down this deal would mean insolvency, missed payroll - and personal liability. George (the interim CEO) and the key go-forward employees demand their $12.5 million carve-out. Tack on more money for lawyers and ibankers, and…

Oh wait, that’s more than $250 million. Oops.

Ergo, Richard ends up with nothing.

So what can we learn from Richard’s grim fairy tale?

Terms matter

Liquidation preferences, participation, ratchets – even the very term preferred shares (they are called ‘preferred’ for a reason) are things every entrepreneur needs to understand. Most terms are there because venture capitalists have created them, and they have created them because over time they have learned that terms are valuable ways to recover capital in downside outcomes and improve their share of the returns in moderate outcomes – which more than half the deals they do in normal markets will turn out to be.

There is nothing inherently evil about terms, they are a negotiation and part of standard procedure for high risk investing. But, for you the entrepreneur to be surprised after the fact about what the terms entitle the venture firm to is just bad business – on your part.

Cap tables don’t tell the real story

For any private company with different classes of stock, the capitalization table is not-at-all the full picture of who gets what in an outcome.

In the above example, each of the three investors held 20% of the stock and Richard and crew held 40%, yet the outcome was vastly different because of those aforementioned pesky terms and preferences.

Before you close on any round, you should create a waterfall spreadsheet that shows what you and each other stakeholder would get in a range of exits – low, medium and high. What you will generally find is that, in high, everyone is happy. In low, no one is happy, and in medium (which is where most deals settle) you can either be penniless or “life-changingly” compensated, depending on how much money you raised and what terms you agreed to. It is simply foolish to sell part of the company you founded without understanding this fully.

This is why it is so crazy to me that many entrepreneurs today are focused on valuation – the grade at the top of the paper. They are willingly trading terms for a high number. Before you do so, run the math on the range of outcomes over multiple term and valuation scenarios, so you fully understand the tradeoffs you are making.

Venture capital is not free money. It’s debt. And then some

People mistakenly think of an equity investment as ‘only’ equity dilution. After all, if you lose everything, your venture investor can’t come after you for your house like a bank lender could. However, most all venture transactions are done for preferred shares with a liquidation preference, which means all that venture money is guaranteed to be paid back first out of any proceeds before you get to make a dime. The more money you raise, the higher that ‘overhang’ becomes. And interestingly, the higher the valuation, the higher the delta of value you need to create before the investor would rather hold on to the end instead of getting his or her money back (or a multiple thereof, as some terms dictate) in a premature sale if things are looking iffy. And what company doesn’t go through iffy times?

Stacked preferences can create massive problems down the line

This one is a hard to articulate in a blog post. Plus, I am a venture capitalist who on occasion puts said senior preferences in my term sheet. They exist for a reason – again often to do with the valuation and the risk/reward tradeoff the investor needs to make using the downside protection of a senior preference against the minimization of dilution the entrepreneur wants to achieve with a sky high valuation. They are not inherently bad.

But regardless of why they are there, the more diversity of value and terms in each round, the more you will create a situation where your investors (who are almost always also your voting board members) will have very different return profiles on the same offer. In the above example (and again I apologize for simplified math but it is directionally accurate) Hooli is getting their $200 million back on a $250 million acquisition. They own only 20% because of the high valuation they paid. So for them to instead double their return, the company would have to go public for $2 billion! This is a case of the bird in the hand being worth more than the two in the very distant bush.

Investors are portfolio managers: You are not

You are betting usually 10 years of your life and all your available assets on your startup. Your investor is likely investing out of a fund where he or she will have 20-30 other positions. So in the simplest of terms, the outcome matters more to you than it does to them. As I noted above, when you have stacked preferences, each person at the table may be facing a vastly different outcome. But now layer onto that their fund or partner dynamics. Ever heard the expression, “lose the battle but win the war?” I’ve seen behavior that would seem crazy, until one considers what is going on in the background. For example in the above, BTV is out raising a fund and depends on that 10X markup to validate their abilities as investors. Facing a write down, a fire sale -- or an extension of runway using debt (and not incurring any accounting change) – which one do you think least impacts the most important thing they are doing right now? For our angel Peter, whose star has risen with this legendary markup, what value is there to him of taking a $1 million loss right now instead of just leaving a walking dead company out there and on his books (although this company is not technically walking dead because, since it is not profitable, it is not walking. But I digress.)

Most reputable investors do not engage in this sort of optics, and many of us who have been through the dot com bust are actually rather aggressive with our write downs to accurately reflect a sense of true value in our portfolios. Also, most investors who are also board members wear multiple hats and take their fiduciary responsibilities very seriously – I know I do. But, I bring up these behaviors because I’ve witnessed them more than once out there in the real world. As an entrepreneur, you should at least think through the motivations of others, both when you are structuring investments as well as when you are considering a sale. They will on occasion matter… a lot.

What to do

Now that I’ve scared you, let me reiterate that most investors I deal with are great, ethical people. If I didn’t think of venture capital money as good for entrepreneurs on the whole, I wouldn’t be a venture capitalist. But we VCs do a lot more deals than you entrepreneurs do, and you need to go into them with your eyes open to the downside consequences of the terms you agree to.

Here’s what I recommend:

Focus on terms, not just valuation: Understand how they work. Read this book. Use a lawyer that does tech venture financings for a living, not your uncle who is a divorce attorney, so you are getting the best advice. Don’t completely delegate this because you need to understand it yourself.

Build a waterfall: Once you understand the terms being offered, build a waterfall spreadsheet so you can see exactly how each stakeholder will fare across the range of potential exit values (yes by stakeholder, not by class of stock: Investors often end up owning multiple classes, and likewise different people in the same class may have very different circumstances that will influence their behavior even in the same outcome.)

Don’t do bad business deals just to get investment capital: I know, duh, right? But I’ve seen otherwise brilliant entrepreneurs get entranced by these big number deals with big corporates, only to deeply regret them later when they cannot be unwound. My advice, separate the business development contract from the equity contract. Negotiate them individually. If the business development deal would not stand on its own merits, don't do it.

Understand the motivations of others: This can be quite tricky, but I believe you should at least think through what might be the motivation of the others around the table. Is that junior partner going to get passed over for promotion if he writes down this deal? Is that other firm fundraising right now? If you don’t know, ask. I always aim to be transparent with the entrepreneurs I work with about what my and DFJ’s goals and constraints are, independent of my role as a director.

And finally…

Understand your own motivation: What are you doing this for? So you can see your face on the cover of Forbes? So you can have thousands of employees working for you? So you can be a member of the billion dollar Unicorn Club? Perhaps it is to do something you are personally excited about and in a reasonable amount of time, maybe take enough money off the table to live in a nice home, pay for your kid’s college and your retirement. I’m not saying one is more correct than the other, I’m just saying that your own goals will dictate whether you should even raise venture at all, how much to raise, and what to spend it on. If you raise $5 million and sell your company for $30 million, it will likely be a life-changing return for you. If you raise $30 million and then sell your company for $30 million, you’ll end up like Richard.

576 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the parent of a trans* kid, I was deeply affected by Leelah Alcorn's suicide. I thought sharing this might help someone else.

I have been thinking for weeks about the suicide of teenager Leelah Alcorn, and her wish that her death mean something.

I’m sharing my story about what it has been like to be the parent of a trans* kid in the hopes that if you are a parent struggling to come to terms with a Leelah or Sabel of your own, this might help —and Leelah's wish for her death to have meaning would take a few more steps forward.

Note: My child Sabel uses the gender-neutral “they” pronoun. [You can watch a video here of an adorable genderqueer person explaining life as they know it.] Sabel has asked me to use this pronoun choice as well so I am doing so in the real world…and in this post. Also, Sabel put in a few editorial comments when I asked them for their opinion of the piece. I have bracketed and italicized these comments and left them in.

When my oldest child, born female, wasn’t even old enough to put a full sentence together, they cried when I put pink shoes on their feet. They would tear them off and pull the white ones out of the closet. “No, these!” they would say.

At five, I asked what they wanted to be when grown up. “I want to be a man,” they said. [As a child, man and woman were still the only two publicized options; genderqueer was a word I would never hear for years.] I told my child that was not possible.

(Spoiler alert: I was wrong.)

For years, we endured challenging wardrobe fights and difficulty with public bathrooms (they would not use a ladies room nor a men’s room, so visits to theaters and amusement parks meant no liquid consumption, and for me led to many frustrating experiences.) Birthday parties were football, laser tag — and all boys. When people mistakenly referred to ‘my son’ and I would correct them, my kid would become embarrassed and ask me not to ‘correct’ people any longer.

When they turned twelve, they told me they were trapped in the wrong body and wanted an operation. Trust me, this was no surprise; appearance and actions for their whole life had never really been that female or feminine. Their father and I had always supported wishes of boys clothing and activities, and we no longer corrected anyone when they referred to our child as our “son.” But then again, our child was twelve, and I did not know anyone else who had ‘changed sexes’ (as we referred to it then) nor anyone else whose child wanted anything along those lines. We talked about surgery and hormone treatment seeming too extreme at that age, and said we’d talk about it again at the age of 18.

Around this time, I looked for help and advice online (there is so much more there now; there wasn’t nearly as much in 2005) and, having no trans* friends of my own, I sought guidance from a good friend of mine — a smart, accomplished, lovely woman whom I trusted and who I felt could identify with the issues my child was facing since she had come out as a lesbian as a young adult and had shared with me some of the difficulties she had faced, not the least of which was with her own mother. I thought she could provide me some parenting advice.

She told me two things which massively helped me. The first, was that there is a difference between sexual identity and gender identity, and even though I might think them aligned because they are that way for me, not all people are like me — but all people’s alignments should be understood and respected.

Second, she told me powerful stories from her time as a youth and a young adult coming out, and having her mom deal (or not deal, as the case was for many years) with her alignment.

“The best, most important, and ONLY thing you can do as a parent is love your child, unconditionally. Their alignment is who they are. Your job is to accept, support, and love your child, that’s it,” she said.

It was life-changing advice for me.

Though that didn’t suddenly make everything smooth sailing.

During high school, my child dressed ‘like a boy,’ kept hair short, and wore plenty of baggy clothes. They endured unkind remarks and outright disdain from some peers — and more disturbingly, some teachers. The high school administration rejected an attempt to start a GSA . High school was not the happiest time. But, at least at home, there was love and support [and NCIS].

College was a happier time — Seattle U has a large LGBTQ community. There are some gender-neutral bathrooms; there are some gender-neutral people. During one of my visits early sophomore year, they told me they had started testosterone and were about to undergo top surgery. I remembered my friends advice, as always. I loved my kid unconditionally.

Now, my child is 21, is named Sabel, has facial hair, a lower voice, and a very sweet girlfriend. We just spent Thanksgiving on vacation together, touring moldy castles and moldier pubs in the Scottish Highlands. We laughed a lot.

Our story has a happy ending, but trust me, the middle was hard. It is hard to be the parent of a trans* child. You go through so much pain seeing them struggle, be taunted, feel different, and have friends turn on them. Sometimes your own family members and closest friends don’t accept your child — and don’t accept you for ‘tolerating’ what they perceive to be odd and socially unacceptable behavior. There are many days you wish your kid would just ‘be normal’ — not because one gender is better than any other, but simply because being mainstream feels like it would be so much easier on everyone, them and you —and also because you simply cannot feel what it is like to be them, so it is hard to relate to why this is so critically important. But it is. And your only choice is whether you are going to love them unconditionally, or not.

When the transition does occur, you as a parent may have some more rough times. You may mourn the child you had because in some ways that child is gone. There may be surgeries; they may have not be able to have biological children [but to them it's like that scene from Alien or like that scene from Prometheus or like that scene from The Matrix]. They are never wearing your wedding dress down that aisle at that wedding you've imagined for 20 years [but mom you have that back-up daughter]. You struggle with names and pronouns at cocktail parties when people ask you about your children — I’ve had more than a few 20-minute conversations after some unsuspecting person innocently asks, “how many children do you have? Boys or girls?”

You will never hear that sweet voice again.

But there is a new voice, a new face, with that same wonderful personality inside, but now that personality is all lit up because it is in a happy body that reflects on the outside who that person always felt like on the inside. Eventually, there comes a day when your child is magically but casually always happy, and your brain naturally says “them” instead of the old pronouns. And you’ve gotten to know this new wonderful person — who is a happier and more contented version of your kid. If that’s not true love, and to be truly blessed as a parent, I don’t know what is.

If you have a Leelah or a Sabel of your own, and are struggling with what to do, I hope this story has helped you see one possible path. Put simply:

Step One: Love unconditionally

Step Two: Recognize this is going to be hard on them and on you, and don’t deny their feelings, nor your own.

Step Three: Trust that, eventually, it is going to feel normal, you will be out laughing together and the world will be okay.

And thank you Sabel for letting me share our story -- Mom

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is the Liquidity Event the Big Reward of Building a Company? Guest Post by Neal East, CEO of Xtime

I've had the pleasure of working with Neal for the last few years as a board member of Xtime. Yesterday, Xtime was acquired by Cox Automotive for $325 million. The Xtime story is a long and interesting one -- not your 'typical' Silicon Valley overnight sensation (which frankly aren't that typical). I asked Neal to reflect on his journey and the meaning of the outcome for him and his team. This is what he had to say...

The Xtime Story

After more than a decade of nurturing a dream into a $325 million liquidity event, I am suddenly at point of my life where reflection seems like an appropriate use of my time.

The deal to purchase my company, Xtime, closed today. It is a fantastic outcome for customers, employees and shareholders and fulfills a life long dream of turning a startup into a big success.

You would think, at a time like this, that all my thoughts would be in the moment. However, as the deal moved to closure this past week, I found myself thinking more and more in the past tense.

Xtime was a unique venture in that it was a turn around. These are rare in the age of the Internet when events and competition move so quickly that a wrong turn usually results in certain death. Xtime was different in that its idea of selling time sensitive inventory; like restaurant seats, hotel beds and doctor’s time, was so big that it could survive being two different companies.

Xtime version 1.0 started in 1999 with the goal of being the “Amazon.com” of the services industry. Rather than selling manufactured goods, like books, it would sell time-sensitive inventory using a platform that could handle everything from hairdresser time to $20 million flight simulator time.

Unfortunately, all of these examples turned out to be unique businesses that required custom applications. However, while there wasn’t a market for a horizontal platform, there was a market for many vertical solutions all based on the same idea. This is clear today with the success of vertically oriented scheduling companies like OpenTable, ZocDoc, Hotels.com and now Xtime.

Xtime was fortunate that its lead venture capitalist, Steve Jurvetson of DFJ, internalized the failure of Xtime version 1.0 simply as a learning experience. It is a common Silicon Valley mantra that failure should be viewed this way - but Xtime is living proof of it.

In 2003, Steve convinced Adam Galper (co-founder and CTO), John Lee (the original founder), and me to completely restart the business from the ground up. With only $1 million in seed capital, we set off to do just that.

Eleven years later, we created one of the fastest growing software companies (according to the Deloitte Touche Fast 500) and transformed the vehicle service experience in the automotive industry. Most surprisingly, I changed myself in the process.

I think I am like many entrepreneurs in that I started Xtime v2.0 with the idea of making a lot of money. Wealth is a powerful motivator and certainly helps explain why so many people take the risk of bankrupting their families to start a business.

However, in the process of building a company with real value, I began to understand that what we were creating had nothing to do with my desires and had everything to do with the universe of people that were affected by this new creation.

This became obvious to me at our annual Christmas party four years ago, when the spouse of one of our employees thanked me for creating the best job her husband had ever had and how proud she was that he had established his “career” with Xtime.

I finally understood. From our employees who risked their futures with us, to customers whose lives were made better by us, to buyers who were promoted because of us, this was the real reward. This decade long journey had changed how millions of consumers got service, how thousands of dealerships ran their business and how hundreds of employees made a living.

This is the real legacy of Xtime, one that will echo long into the future and is the final, true measure of our success.

-- Neal East

CEO, Xtime

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The best perks to retain working women? I think it's what you DON'T do that matters most.