Text

Blog twelve - Project in Process

Ironically, a lot of effort went into creating the different mediums. I did this, however, in order to show that no matter how much the medium may transform, the meaning of the text does not. As I said, materiality may add another dimension to the texts meaning, or enhance the reading experience, but ultimately, the medium is not the message: it is the text. The text allows for interactivity in whatever form. It is like its own spiritual phenomenon: it has the ability to transcend the medium.

Painting the Illuminations.

Making the Nag Hammadi version.

My first attempt at the outer cover.

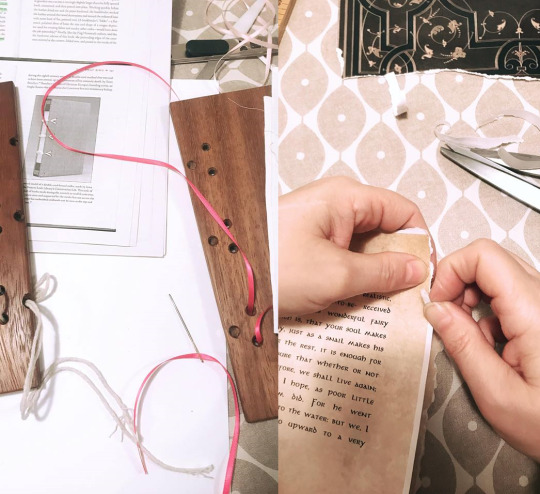

Trying to work out how to put the Double Cord Bound version together.

Sewing together the Gutenberg version’s pages.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog eleven - Making the Project

As my previous post discussed, the aim of incorporating five different versions of the book in my project, is to try and exemplify that in changing the medium, I have not transformed the meaning of The Water Babies. In order to try and reflect this idea in my project, I have made a Water Babies version of each of these forms of the book.

The first version is based on the leather-covered papyrus books known as the Nag Hammadi codices. They are the world’s earliest complete bound and covered books. In order to make my own, I was able to source papyrus-like paper and (with great difficulty and the fear of breaking a few printers) I was able to print the Water Babies passage, using a papyrus font, onto it. With this version, and the next two, I thought that printing onto the paper using a font would be the most practical means of getting the text onto the page, as my first efforts to hand-write effectively in the appropriate font was pretty abysmal. But at least in doing so I am sort of engaging in the module material as it shows how I used the digital to facilitate the production of the early codex. I then cut up a leather handbag to get the cover of the Nag Hammadi-like codex and some leather throngs. Using these I was able to bind the papyrus and leather together, making my own version of the Nag Hammadi codex.

The next version is based on the double-cord bound stitching that came just after the likes of the St Cuthbert Gospel (popular between the 7th and 12th centuries), as it offered a stronger alternative to Coptic stitching. Ancient bookmakers would have realised that papyrus was not accommodating for this method as it involved groupings stitched together at the spine, with the spine visible. So, I decided to impose a vellum-parchment image onto the background of my paper with the font onto of it, as for-some reason, it was difficult to find handmade paper that I could have used as an alternative. I then had two thin wooden boards made as the cover. These boards were often finished with a leather cover, but I wanted to show how the book had evolved so chose to emphasise just the wooden boards. Obviously I have not made an exact replica of this version, or indeed any of the versions. What I am trying to do is utilise the most defining features of each form to present how the book has evolved.

The next version is based on the Gutenberg Bible, which marked the age of the printed book in the West. In order to try and reproduce this, I included illuminations on the first page, alike those from the actual Gutenberg Bible. These were just painted on using gouache paint and it is probably the most creative thing I did for this project. It is the pages which I focused on most here, and I tried to include a font that closely resembled the one Gutenberg used himself. Just to have a cover like the rest of my versions, I got an image of what the Bible’s cover looked like and printed that out. It was then attached to the sewn pages using double-sided tape.

For the modern day version of the book, I just used my own copy of the water babies, which I used for my Literature and Science module last semester, as I figure there was no point in recreating one when I could use the actual thing. I tied two halves of the book in ribbon so that only the relevant pages are shown, and just marked where the passage starts and finishes.

The kindle was probably the hardest version to reproduce. I thought using an actual kindle would be quite troublesome as I myself don’t own one, and if I were to borrow one it could run out of battery or something. So, as I created reproductions of the earlier forms of the book, I created a reproduction of the latest form. Using my aunt’s kindle, I downloaded the Water Babies and photographed the relevant pages, while changing the colour of the background for each page just to show the possibilities of things the kindle can do, as well as it’s being able to change font and font size. I then incorporated them all into a sort of box, which will be more understandable when viewing the final product. I wanted to show that unlike a book, the pages aren’t turned, instead they are almost swiped across. So I included tabs on the edge of each page so that the page could be pulled out as you go. I am trying to just show how different the kindle, or even any form of tablet is, from the Nag Hammadi for instance.

I hope that in making these five versions of The Water Babies passage, it shows that whether papyrus, wood, illuminations or even digital is used, the text remains the same. Its meaning has not been transformed as the medium has been. Therefore, I think it is conceivable to state that the medium is not the message. Any adaption of the book will convey the text which Kingsley originally wrote. This is why I have decided to bind all five versions into one greater version, which is covered by one of the first Victorian editions of the novel published. (In a practical sense, then, I attached each version to card and covered a lever-arch file with the Victorian cover. Initially I had attempted to make it from a book that I had deconstructed. I had screwed a ring binder to the books cover, but the width of this was not large enough to accommodate the five versions of the book. The intention is still the same with the file though, as it allows each version to be moved along just like the pages of a codex are turned. Therefore, it is as close to resembling a book as I could get it).

References:

Keith Houston, The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time (Norton & Company: New York, 2016).

0 notes

Text

Blog ten - Project

In order to explore this idea that the text transcends the medium, I have selected the novel The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley. I did so because I think it has connotations with the concept I’m trying to present: that the text is its own spiritual phenomenon. In the text, Tom, having become a water baby, has underwent a spiritual journey in which the shedding of his previous physical land-form, for the form of a water baby, facilitated the cleansing of his morality.

The passage I have chosen also reflects this notion, as it questions whether a person’s body should constitute their soul, instead advocating that “your soul has nothing to do with your body”. I have taken this as almost reflecting the premise of my project: that it is the literary text which is almost like the soul, and the medium which is the body. Therefore, I hope it reflects the idea that meaning and materiality are not indivisible and that the text should have greater precedence than materiality.

In my project, then, I am reproducing this same passage of text in different forms of the codex. I have chosen to replicate the Nag Hammadi codex, a double-cord bound codex, the Guttenberg Bible, the typical book we use today and a Kindle. I think these effectively represent the history of the book and the evolution of the codex from its inception. I hope that by producing the same text in five different mediums, that it will exemplify that different mediums do not change the message of the text. This should therefore reiterate the arguments I made relating to interactivity and the impact of digital technology on the printed book: that it is the text itself which creates interactivity, and that we don’t need to fear technology or worry that the book is an outdated medium. I am essentially hoping to just consider and explore the notion that we give too much precedence to the medium. It is the text which provides meaning and which we interact with most, and so it is the text which allows a reader to transcend the material form of the book and gain experience from imagination.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog nine - Beginning my Project

My project relates quite closely to what I talked about in the previous two posts about interactivity, and the impact of digital technology in the printed book, and correspondingly, the death of the book. With the increase of digital technology, there appears to be an increasing pressure on materiality. Yet, in considering everything I have previously said about how the printed text was already interactive, I don’t think that meaning and materiality are indivisible, even though that’s one of the concepts explored in this module. I do think that text can be meaningful without engagement with its materiality, which essentially disagrees with what Marshall McCluhan said about the medium being the message. (This video details McCluhan’s claim that ‘the medium is the message’). This is because a text engages each reader differently and allows them to take something different from a given text.

I’m not, however, arguing that materiality isn’t significant, or even just cool, because it definitely is. Just look to my blog post for ‘the book unbound’: I obviously think materiality is incredibly interesting and can really enhance the experience of a text. Nonetheless, I don’t agree that materiality determines or changes the meaning of the text, as people like Hammond and McCluhan would have us believe. I think it merely adds another dimension to the meaning. In that sense, I think that we might give too much precedence to materiality, and perhaps the medium isn’t the message. It is worth considering the text’s ability to transcend the medium, because the text is sort of its own spiritual phenomenon, and I hope my project will exemplify this.

This kind of reminds me of those cheesy quotes about books that used to be pinned up around the library or in my English classroom when I was younger. While these are unquestionably cringe-worthy, the sentiment behind them is not unlike what I’m trying to convey with my project.

0 notes

Text

Blog Eight - Book was There

The impact of digital technology on the printed novel has resulted in worries about the future of the book. Robert Coover’s The End of Books, declared “the print medium has come to its end”. Print, he prophesied, would be replaced by the digital medium: the novel, for its part, would be replaced by hypertext fiction.

In his seminal essay, “the death of the author”, Roland Barthes argues for the restoration of the place of the reader, rather than having the author impose limits on the text. Critics like Hammond think that this is only achievable with technology, and that it is the digital which will transform writing. Régis Debray says that with digital technology, the reader is “no longer simply spectator… but co-author of what he reads”. However, I think that the reader has never merely been a spectator, because, regardless of how authoritative the author wants to be, the reader has always done what he/she wants with a text and has always found their own path. I also think this fits in with what I previously said about the interactivity of texts. Literature has always been interactive in allowing each reader to do different things with a text. Therefore, as critics such as Wolfgang Iser and Stanley Fish believe, while the author puts the words on the page, it is the reader who brings them to life through the process of reading. In The Reading Process, Iser argues that the literary work possesses “two poles”: “the text created by the author” and “the realisation accomplished by the reader”.

I feel, then, that technology isn’t threatening the book because the book already does what technology is claiming to do: creating an interactive experience for the reader. At the same time then, technology doesn’t need to be feared because it is not facilitating the death of the book. Therefore, while I myself would prefer to read a book in the traditional sense (whether because of familiarity, nostalgia or neo-luddism I’m not entirely sure), things like the kindle and eBooks shouldn’t necessarily be criticized. Either way, it’s the text that’s providing this interactivity, so really the medium shouldn’t matter much.

I think this is beginning to set up the idea for my project, and reminds me of a quote from a video from my first blogpost.

youtube

From 3:42, the video says, “As the book evolves and we replace bound texts with flat screens and electronic ink, are these objects and files really books? Does the feel of the cover or the smell of the paper add something crucial to the experience? Or does the magic live only in the words, no matter what the presentation?

References:

Adam Hammond, “Interactivity: Revolution and Evolution in Narrative’ in Literature in the Digital Age (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Régis Debray, The Future of the Book, 145 (1996).

Wolfgang Iser, The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach’ in New Literary History, Vol. 3, No. 2, (Winter, 1972).

0 notes

Text

Blog Seven - Interactivity

Adam Hammond said that literary narrative doesn’t have the interactivity of the digital. Pry, for example, is said to offer a sophisticated approach to medium, allowing the ‘reader’ or ‘player’ to be both inside the soldiers head and outside. He claims that with the digital book there is so many more options and that it is always updateable. Yet, while people like Hammond suggest that a new digitally saturated form of medium will ultimately displace text, I disagree, because the affordances claimed for digital were always there in inscription. Hammond implying that reading a text is fixed, closed and producing the same experience for everyone, is not the case. Textuality trumps this simplistic notion of interactivity because each reading of a text exceeds one’s previous experience with it. Readers can take away something different from a reading, meaning the experience of reading is therefore with the text itself and what it can do. Essentially, its possibilities are limitless. Whereas digital, bound by the fact that your apparent freedom is highly circumscribed and premeditated means you get an empty thrill. So there are significant limitations to digital. It doesn’t pose the kind of questions that a complex poem or story will pose. For example, if you know Catullus 101, and you read Nox, with all the intertext of Catullus then,you are bringing in the meaning of other texts to the text. It’s a multiplying of meaning. With games like Pry it’s just an illusion of meaning. So then, literature was, contra Hammond, always already interactive.

Moreover, aside from the obvious interactivity then that comes with reading texts, its interesting to look at books like House of Leaves and S: Ships of Theseus which actively attempt to produce an increased interactivity. Katherine Hayle’s Writing Machines refers to the special role that these kind of books play in the conception of the future of the book, opening up new structural and expressive possibilities. S: Ship of Theseus’ interactions between the readers in the margins as well as the additional inserts are so cool. It really exemplifies that text can still be used in the same complex ways that digital technology is used, to create an advanced interactivity.

References:

Adam Hammond, “Interactivity: Revolution and Evolution in Narrative’ in Literature in the Digital Age (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Katherine Hayles, Writing Machines 64 (2002).

0 notes

Text

Blog Six - Magical Books

What I found most striking about Magical books, is the prominence of religious elements they contain. The Bible perfectly demonstrates the difficulty in demarcating the line between the magical and the religious. While it was obviously not a Grimoire, Owen Davies claimed that “the power of the words, stories, psalms and prayers it [contains], as well as its holiness as an object, [make] it the most widely used magic resource across the social and cultural spectrum over the past thousand years”. Owens references the Biblical account of Moses to underpin this notion that religion bears directly on the grimoire tradition. The first can be found in Exodus, in which Moses and Aaron turned the rivers and pools of Egypt into blood and summoned up a plague of flies during a magic context against the Pharaoh’s wizards. The second is his discovery of the two tablets bearing the Ten Commandments during his revelation on Mount Sinai. Owens said that “the former sealed the tradition of Moses the magician while the latter was the source of myths regarding the divine transmission of more secret knowledge than in mentioned in the Torah and Old Testament.

“So Moses and Aaron came to Pharaoh, and thus they did just as the LORD had commanded; and Aaron threw his staff down before Pharaoh and his servants, and it became a serpent” Exodus 7:10

This is only one example that Owens draws upon, but from this alone it’s evident that Magic was quite a grey area. In fact, grimoire authorship was often associated with those of Christian piety. Appearing at the turn of the eighth century, grimoires were possessed by a clerical underground, as priests were the only people who could read and write them. The number of clerics who were attracted to concepts of high magic, then, attests to the clerical underworld practising rights we’d recognise as magic. Church authorities even became so concerned with their priests being led astray that in 694, the Council of Toledo issued an edict stating ‘it is not permitted for altar ministers or for clerics to become magicians or sorcerers, or to make charms, which are great bindings on souls’. This idea that the line between religion and magic is blurred is alien to us today, but the history of magical books is evidently bound up in the Christian tradition.

0 notes

Text

Blog Five - The Book Unbound

This week’s lecture offered a differing process to what I wrote about textual interpretation and indeterminacy in Blog Three. The Postmodernist concept attacked the notion of realism, and instead postulated that the reader should become a co-creator of reading rather than a passive consumer. This led to the idea that the author should be put to death, with the likes of Roland Barthes revolutionary work, ‘The Death of the Author’, declaring that the idea of authors as secularised gods should be overthrown. Indeed, many authors then started playing with such an idea, and began placing the reader in the position of the protagonist. We discussed how this is the case with B.S. Johnson’s ‘The Unfortunates’, because his decision to break the book up into booklets that are to be assembled means the reader becomes a creative force in literature, not the writer. This effectively challenges authorial authority. Also, the idea of cut-ups is pretty cool, and is basically the ultimate assault on authorial authority. I don’t think Nabokov would appreciate that very much.

We then moved on to Nox, in which this whole authorial authorship thing was also kinda discarded. What I love about Nox though, aside from the actual narrative about her brother, is what she did with the material form. It’s a fusion of print and digital. Kiene Brillenburg Wurth talks about remediation and how Nox reworks old media within new media and vice versa, so that the end result is a digital reproduction of her personal book that has been repurposed in the antiquated form of the screenfold, but at the same time constantly represents staples, personal photographs and a collection of letters and papers. This form really enhances the experience of reading as well as its distinct features.

I’ve been researching similar works that really explore the different material forms that the book can take. Victoria Macey’s Bodoni Bedlam (shown in the video), is a pop-up alphabet book that plays with letters and employs them in new and creative ways. Ulises Carrion “positions the book as an object, a container and a sequence of spaces”, as opposed to a text (Adema and Hall 11). Therefore, in the case of Bodoni Bedlam, the eponymous font, Bodoni, is re-purposed to serve as element of illustrations for the story, and even by identifying the font, potential connotations associated with it are considered. More than this though, it offers an experience of reading impossible to achieve by digital means, in the same way that Carson said Nox was un-Kindle-isable.

vimeo

Also, since Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 was mentioned earlier in the module I’ve been pretty enthralled. I haven’t got round to reading it yet, but the concept is so clever. So, the narrative is set in a future where books are forbidden and any copy found is burnt by ‘firemen’ and the title refers to the temperature of autoignition of paper (approximately 233 degrees Celsius). The materiality of the book reflects this concept as the cover includes a match and striking paper surface on the spine, reminding the reader of the fire-prone nature of paper books. In doing so, the artist used the materiality of the book to reflect for instance, the fragile nature of books, their importance as carriers of knowledge and the suppression of ideas in this text. As Jakob Dutka said, each of these “approaches to materiality contribute to exploring the ‘outdated’ medium and contribute to its re-invention”.

References:

Adema, J. and Hall, G. The political nature of the book : on artist’s books and radical open access. New Formations, volume 78 (1) :138-156 (2013)

https://mastersofmedia.hum.uva.nl/blog/2014/05/19/book-as-a-reflexive-medium-the-materiality-in-post-digital-print/

0 notes

Text

Blog 4 - Reading Revolutions? The Coming of Print

This week we embarked on that elusive debate about whether or not the Gutenberg printing press constituted a revolution.

youtube

I did the History of English module last year and we touched on how printing had helped standardise the language, among many other things and I also did a module called Revolutionary Europe in History in which printing was involved. I’ve just assumed then that it was a revolution. Elizabeth Eisenstein is of this opinion, believing that printing was associated with rebellions, emancipation and most importantly, fixity. The fact that she aligned herself with Protestantism, however, slightly undermines her argument, as it doesn’t account for the fact that the Catholic Church utilised printing themselves in the Counter-Reformation.

Aside from this, we often fall into the teleological trap of assuming that because printing facilitated more numerous printed books than medieval manuscripts, that it was better. This, however, was not necessarily the case. For one, print doesn’t always last, with only 49 of the 180 Gutenberg bibles still around today, and printing introduced a culture of speculative production, with some believing that time was not really saved in print, except speculatively. Moreover, the technology of printing wasn’t an entirely new nuance, as Gutenberg had drawn upon existing wine making technologies and adapted that.

In fact, referring to print as an abolsute revolution must be contested on the grounds that the printed book emulated the appearance of the manuscript because it had to enter that market and compete. It did not, then, generate some profound “agent of change” as some would believe. The same can be applied to the so called ‘digital revolution’. Digital, for all its talk of revolution, is rehearsing so much of book culture. Apple books, for instance, are trying to reproduce the activity of reading a physical book, by making their digital reproductions contain such effects as illustrating the different pages in a book. Digital as a whole appears to find its routes in the history of the book. Just think, when using a computer you’re seen to be scrolling through various web-pages, just as ancient and medieval scribes would have unwound scrolls.

Screenshot of an Apple Book.

It can be said then, that print can only be considered a revolution to an extent.

0 notes

Text

Blog 3 - Cultures of Commentary: the Book in the Middle Ages and in Postmodern Fiction

In this week’s lecture we learnt that Umberto Eco basically parodies the whole concept of textual interpretation and Gnosticism. He said, “the hylics – the losers – are those who end by saying ‘I understood’”. I quite like this idea that maybe not everything has a constitutional meaning, and so apparently did Vladimir Nabokov as this is essentially the game he was playing when he wrote Pale Fire. This novel is something like a parody of academic literature because it satirizes the idea that this community seeks to replace the text its supposedly explaining. It’s ironic then that an online community of commentators was generated in response to this work, and I myself similarly attempted to decode it all, assuming that perhaps Kinbote is completely mad, that maybe Shade didn’t actually write the poem, or even that Kinbote was pretty much in love with Shade and was kinda stalking him (he did spy on him from his various vantage points like the ivied corner at the end of the veranda) and that’s why Shade’s wife was always a bit cold towards him… So we all essentially fall into Nabokov’s trap, proving him right. This whole idea then of reading a book without attempting to pin down the authors intention or meaning is so appealing to me, probably because I’m quite sick of having to explain intelligently why I liked a book in tutorials, as opposed to saying I liked it just because. I don’t know if that’s what Nabokov was intending but that’s what I’m going to take away from this nonetheless. (Am I again falling into his trap by wondering if this is what he was intending or not?)

This whole concept of parodying textual interpretation was further explored as we moved onto the post-structuralist theory of indeterminacy, which basically meant that the capacity of language to be unstable prevents us from closing down the meaning of text. We therefore have the idea that ‘meaning’ is difficult to determine. The instability of meaning, which we saw that Eco and Nabokov were basically subscribing to, can also be attributed to manuscript culture as well as print culture, especially because things were being repeatedly copied by scribes with various errors and divergences. It appears then that all texts, whether pre or post ‘printing revolution’, are unstable in their material context. Can we then say that books as things suffer from materiality? Possibly.

0 notes

Photo

We are always thrilled when new students discover our Special Collections!

Pictured above, MICA freshman Wyatt Mitchell set up our tables so he could view some of our Japanese Scrolls from our Special Collections.

The scrolls are:

Scroll of Heiji Monogatari Emaki (ND1043.4.S27 Cage).

Scroll of Shigisan Engi (ND1043.4.S27 Cage).

Scroll of the Frolic King Animals: Choju Giga (ND1043.4.S27 Cage).

Want to see something from our special collections? Ask a librarian to grab it for you!

627 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Two - The Book as a Thing

When discussing the Book as a Thing in this week’s lecture, I was intrigued by the concept of reciprocity between subjects and objects. Christopher Tilly deduced, it is not the case that “subjects and objects are regarded as utterly different and opposed entities, respectively human and non-human, living and inert, active and passive, and so on”. Instead, it is “through making, using, exchanging, consuming, interacting and living with things [that] people make themselves in the process”. Our social being is therefore constituted through our interaction with the stuff we use, and indeed the books we read. I like the idea that we come into being partly as a result of our reading a book, and wonder to what degree my identity has been shaped or extended by the material that I have read.

The tour in the Special Collections Reading room was also pretty fascinating. I was probably most interested in the Alchemical Manual, not only because of the somewhat magical element of it, but because its cover was bound by recycling a ‘crappy’ medieval manuscript. This again got me thinking of the things I could perhaps try in my own project, as did the Mein Buch copy, which was created in nineteenth century Germany as a faux Medieval book, about Egypt. Together with last week’s reading on the different methods of binding that have been utilised, I’m really trying to piece together something which could incorporate these kind of elements. It also strikes me just how old these books are, (in want of a better phrase), when considering the new technological versions of books, whether kindles or websites like the Library of Babel one. Maybe for my final project I’ll be able to incorporate the earlier versions of the Book, and the most modern…

0 notes

Text

Blog One - Texts and Textualities

The readings for week two, I think, offered an effective introduction to this module, dealing with such themes as prefiguration, as well as the relationship between literature and technology.

I was struck by the similarities Forster’s ‘The Machine Stops’ shared with H.G. Wells’s ‘The Time Machine’ when I first read it, with each narrative offering a somewhat formidable warning against modifications of society. They both recognise that technology is telling a story which is antithetical to where we want to go as humans, with the advancement of technology in these instances resulting in the absolute alienation from nature, and henceforth, from human nature. Moreover, ‘The Machine Stops’ could easily have been a modern text as it revealed a striking proximity to our own experience with technology almost one hundred years later: it predicted instant messaging, and imposing social networks now, as opposed to actual relationships.

Borges’ ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ appeared to explore a similar theme of prefiguration. He appeared to be imagining, or predicting a form of hypertext in detailing Ts’ui Pen’s Labyrinth. But, just like Forster and Wells offer a criticism of the culture technology produced, Borges appears to offer criticism of the entirety of human literature. He explores intertextuality in suggesting that the history of literature is in itself a history of the retelling of history, that all texts are quotations of other texts. It’s most likely a stretch, but this apparent criticism of written culture reminds me of Plato’s complaint about writing discussed in the lecture: the idea that oral cultures are resistant to technologies of writing because it makes things authoritative, and creates a canon of behaviours/ideas which brings about the loss of the community who kept it alive before the written text.

Then, with Houston’s ‘The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time’, the intricate details it divulged on bookmaking, such as the particulars of binding in the Nag Hammadi Codices to the stronger double cord binding that emerged around the eighth century, has me mulling over various ways in which I could go about creating my final project by perhaps using these earlier forms of creating codices. However, it is essentially only the first week and as I continue to learn more my initial ideas will most like evolve and change. Hopefully.

One of the Nag Hammadi Codices.

An example of the Coptic Stitching on Ethiopian manuscripts, which would have been used in the St Cuthbert Gospel.

An Example of what a double-cord-bound codex would look like from Houston’s book. Typical of books made during the seventh to twelfth centuries.

I found this video outlining the evolution of the book.

youtube

References:

Keith Houston, The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time (Norton & Company: New York, 2016).

0 notes