Text

Where Will The Baby Go?

For something that weighs around three kilos and measures in the region of 50cm, newborn babies sure do take up a lot of space. A little shy of three weeks ago, we brought our second baby back home—the same home we had brought back our first, just over four years ago. Many things have changed since then, not least the number of grey hairs on my head, but the one thing that has remained resolutely unchanged is the footprint of our apartment.

The fact of this sat with me all through 2022 and 2023, as my husband and I journeyed down the path of growing our family and all the complexities (read: hope, loss, love) that kind of process often entails. But where will the baby go? I'd silently fret to myself before I was even sure I’d have a baby at all to hold in my arms again. Objectively speaking we live in a small apartment, with enough bedrooms for two-thirds of the current occupants, excusing our enormous house cat who cares not for doors or boundaries and considers any available surface her territory for a hard-earned nap. To be honest, I’d welcome that kind of laissez-faire approach to our sleeping arrangements, flopping from sofa to bed to rug, but social conditioning and my extremely Type A personality requires routines and structure. No, the baby would need a bed, just like the rest of us, and we would need to work out where that bed was going to go.

It’s a profoundly modern and Western phenomenon, this suggestion that each individual requires their own bedroom or even their own bed. In the majority of countries around the world, co-sleeping and room sharing between parents and children is the standard practice of care, to the extent that it would be considered completely unreasonable to expect a child (let alone a baby) to sleep alone. In Japan, where co-sleeping ranks the highest in the world, sleep is described as a river, with the parents occupying the banks and the child as the flowing water held safely between. We co-slept with our daughter for the first six months of her life, although it wasn’t in the formation of a river but more like a motorbike (our bed) with a sidecar (her crib). Given the grunts, hoots and whistles she regularly emitted as she dozed, this analogy feels more apt than the backdrop of a babbling brook. In any instance, she was never more than an arm’s reach away during those thick, dark nights when every insane sound she made was heightened in the silence of a slumbering home. After that, we moved her into The Baby’s Room which we had decorated and furnished with playful odds and sods that said more about our whimsy of being parents than they did of any perceived personality trait of our child. It’s a curious thing, to decorate a room that someone else will occupy, without knowing a single thing about their tastes or interests.

The Baby’s Room had also been our study until that point, and when the time came to move the desk into the front room to make way for a changing table and crib, I felt slightly undone. I was ready to acknowledge that parenthood would come with an exchange of gains and losses, but there was something so bluntly literal about the act of becoming a mother that it necessitated my giving up a private place to write. I guess it’s a variation of that oft-debated line from Cyril Connelly: “There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hallway." The irony is that it was only once my daughter was born that I found the capacity within myself to put pen to paper in a more expansive way, and during my maternity leave I wrote the first draft of a book proposal. Perhaps it’s an even greater irony that four years later I am writing these words whilst my son is wailing in the room next door, as my husband tries to rock him to sleep. Perhaps, like nature, art will always find a way.

One of the consequences of giving up our study in place of The Baby’s Room, was the associated shame (entirely on my part) that came with living in a home that appeared too small for all our needs and wants. I come from a country that places a great deal of emphasis on the Family Home, variations of which most of my peers now live in and are currently extending, remodelling or digging out extensive basements underneath. Family Homes have a garden, enough bedrooms for everyone, a guest room, more than one bathroom, and the kinds of open plan kitchen-cum-dining rooms that are increasingly of a single aesthetic that populates all our Instagram feeds. Family Homes tend to come with their own social media accounts, so we can follow our friends’ #HomeReno updates and post fire emojis under pictures of construction sites. I have spent a good many years reflecting on what makes us feel good, mad and sad about home, and I can tell you that the insidious rise of interior design content which is beyond the skills and budget of the overwhelming majority is making a lot of us fucking miserable about our living situations.

After a while, the question of where will the baby go stopped masquerading as a concern about where, practically, the baby will sleep, and revealed itself for what it was: a shameful desire to meet some kind of social norm as a Family of Four. This revelation came to me in the winter of 2022, after a shockingly awful year pockmarked by loss. During this time we had tried, and failed, to sell our apartment and buy a house. For nine long months our home sat on the market, and most weekends we spent our free time cleaning and decluttering so the estate agent could bring one or two people over for a viewing that never materialised into anything other than a pass. That weekend, in early December, when we pulled our home off the market and accepted our fate, I wept. It was another grief, of sorts—the ambiguous loss of a life I had imagined in our new house; one with enough potential to become a Family Home.

These days, when I’m feeling a bit out of sorts at home and in need of a reset, I roam around the apartment and find things to fix or do—packing toys away in their rightful boxes, folding laundry, changing lightbulbs, that kind of thing. Invariably, I’ll end up standing in my daughter’s room gazing at all the things that make this space sing with her personality that we could never have anticipated when we picked out paint colours—the paintings bluetacked at a wonky angle on the wall, the rock and gravel collection, the basket of teddies, the plastic box stuffed with countless beaded bracelets she’s made for us all. I can’t even remember what it looked like when it was a study, and I don’t care any more. I didn’t lose anything when I moved my desk out, because it was never a trade to begin with. The day we turned that room into our daughter’s bedroom, we simply dialled up the joy in our lives. I couldn’t see it for a long time, but now I know that I’ve been living in a Family Home all along.

So where will the baby go now that we are four and our home is still, resolutely, the same size as before? He’ll go right here, of course—with us.

0 notes

Text

One Of Those Lists Again

I’ve just turned 40. In those four decades, I’ve lived and worked in five countries, moved home around 20 or so times, and done jobs in more than 24 different kinds of places from the age of 15.

Those kinds of numbers aren’t that unusual, particularly for Elder Millennials like me who found their opportunities and trajectories accelerated by the Internet. We are the cohort who remembers the agonising wait and drop of landline dial up Internet whilst we were studying in High School, but have every reasonable expectation today that we can do the entirety of our knowledge economy jobs wherever and however we want with a seamless wifi connection. We had the chance to make fools of ourselves learning how to be someone before people could take photos and videos and tag us on social media, but bathe in the benefits of technology that makes holding down a job, running a household and growing a family easier than any generation before us.

Anyway, because absolutely no one asked for it and despite many greats having done this far better than I ever could, here are 40 things I have learned in that time:

Nora Ephron was right, you’ll regret not having worn a bikini for the entire year you were 26.

Remember to send that thank you note: for Christmas presents, for party invitations, for job interviews, for the bouquet of flowers your friend sent you when the Very Hard Thing Happened.

Anyone can rustle up a please or thank you, but showing up on time is the most effective way to show respect.

You’ll never regret traveling. Even the worst adventures are worth their weight in anecdotes.

Not everything can be reached through relentless pursuit; sometimes you need to sit still awhile and wait for it to come to you.

Your gut is as complex as your brain. Listen when it tells you things.

Whatever they taught you in school about reproductive health is so lacking in substance that one day, decades later, you will find yourself in a doctor’s office whilst they show you a laminated diagram to explain how ovaries work.

Even then, you will learn something new and overwhelming about your body every time you see a medic.

The things you tell yourself in your twenties that you cannot possibly do are almost certainly the things you will face in your thirties.

You will hurt the people you care about. It’s the price you pay for loving and being loved in return.

Not everyone will like you.

You’ll get things horribly wrong and disappoint people who thought you could do better. You will probably do this more times than you’d like to remember. Some of these moments will still make you burn with shame at night when you can’t sleep, many years later.

It’s never too late to repair the rupture.

Nothing is ever equal in a relationship, but it should always feel fair.

Don’t save nice things for a special occasion. Wear the shoes, use the plates, burn the candles. Life’s too short.

Find a way to talk about money with your partner, even if it makes you want to peel your own skin off.

Do something properly or don’t do it at all. People will know if your heart’s not in it.

We all turn into our parents eventually. But you get to choose which parts you take, and which you leave behind.

There’s no job worth doing just because it pays well or looks good on paper if it makes you cry every morning on the way to the train.

Be prepared to revisit whatever timeline you’ve set yourself. Again. And again. And again.

At some point, the place you call home will stop giving you everything you need and it will be time to leave. Sometimes you’ll see it coming down the road and sometimes you’ll wake up in the middle of the night with the realisation. This is how it goes.

Remember to wear sunscreen.

If you’re lucky, someone will give you feedback so critical you feel like your skin might blister. It’ll confirm every worst thought you’ve had about yourself, but in time it will act like an inoculation against future harm.

As a woman in leadership at work, you can be good at your job or you can be liked. Entrenched sexism and numerous studies show that you can’t be both.

Just because someone said it, doesn’t make it true.

Having a child is like watching your heart leave your body and walk around on the outside. You will never recover.

There will be times when you experience loss and grief so gutting that your insides will feel bruised. And yet you still don’t know the half of what’s to come.

Words matter.

Early on in your life you will make choices that are different by only a matter of one or two degrees to those of your friends. But as time goes on, and you continue to walk your respective paths, you will find your realities have moved continents apart. Send a postcard every now and then.

Some of your closest friends, with the nearest of realities, will live on literal other continents from you. Those friendships will endure, even when you only see each other every few years.

Try not to go to sleep on an argument.

Cut flowers are extravagant, wasteful, and unsustainable but you will continue to buy them by the armful because they bring you so much joy.

Some things will make you shudder at the thought.

You will do them anyway.

Just get in the goddam photo.

Don’t say things about yourself that you wouldn’t say to someone else.

A well timed joke will always make it feel better.

There are very few hard and sad things in life that are beyond the immediate salve of popping on the kettle and making a cup of tea. Always knowing that you can do this first gives you time to work out what to do next.

Education is a constant and lifelong journey. So is love.

What are you waiting for?

0 notes

Text

The Winter Bathers

I’m a woman for all seasons. They help me carve up the elephant-sized year into something manageable, so I don’t freak out at the prospect of 365 unchanging days. I joke with friends about the abject misery of cold and wet winters in Denmark, where I have lived for the last eight years, but I inwardly rejoice at the cashmere and candles and casseroles that accompany them. I always think of that Bill Hicks line on people who live in L.A bragging about it being hot and sunny every day: “What are you, a fucking lizard?” Our summers are so much sweeter in Scandinavia for knowing we’ve weathered the worst and we’re duly rewarded with long days, soft breezes, and lush greenery. If you’ll allow me a moment of cringe, I believe that the seasons teach us the power of rituals. And rituals are how we endure.

There’s a saying in Denmark which you learn pretty fast when the first cold snap hits: there’s no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing. Which is all well and good, but does nothing to explain the frantic energy with which the Danes also remove all their clothes entirely and throw themselves into the sea during the coldest months of the year. This particular form of brutality is known as ‘winter bathing’, a coy name which implies retreating to some Edwardian copper tub filled with steaming, eucalyptus-scented water whilst the snow falls gently outside. The reality is a gaggle of naked people, nipples to the wind on a frozen pontoon, wading into water colder than the base temperature of my fridge.

I moved to Denmark during a heatwave. Those first weeks in Copenhagen were spent in a spritz-fuelled haze as the long summer days melted into ambient warm nights, and I did little more than bounce between the bars and cafes that lined the historic canals and cobbled streets. When I filed the papers for my residency card and was asked to give the reason for my relocation, there was no box for me to tick. I had no job, no studies, no family here to reunite with. I had, quite plainly, moved for life. And Copenhagen appeared to be where I was best suited for living it. Even the inevitable winter, and my staggeringly bad clothing, couldn’t diminish the joy with which I embraced my new hygge lifestyle. I lit a lot of candles, I consumed vast quantities of buttered potatoes, bread and pastry, and I persisted in ordering glasses of red wine in local dive bars that only served beer on tap. Denmark and I—we were made for each other.

By the time I was ushering in my third winter, I’d leveled up my clothing to include the kind of coat that stops people dying on the side of Mount Everest. I’d completed my first ‘Viking biking’ experience having cycled in snow without losing my mind or my two front teeth. And I’d also moved to a neighbourhood in Copenhagen that is locally known as “Shit Island” for reasons that seem to involve a blighted history of municipal waste disposal and a whispered disdain of working class people. It offered affordable housing that was minutes away from a protected nature reserve and one of the city’s longest and cleanest public beaches. And that was where I first saw them: the Winter Bathers. A mass of flushed naked bodies waddling around the turquoise wooden dock at the top of the beach whilst I was scowling at my partner through the biting wind, my survival gear zipped up to my nose.

I’d had a primer on European nudity when I went skiing with some friends in Austria a few years earlier. I say “I went skiing” but this is a significant overstatement of the facts given I had never placed a single ski boot on my feet before the trip. “I went crying on the side of a mountain whilst my friends had a blast” would be a more accurate description for the “holiday” for which I forked over vast quantities of cash I could not afford. I can think of no other experience where you pay so much to be routinely hurt and humiliated, aside from the kinds of activities that take place between consenting adults in sex dungeons.

After three days of crying on the side of a mountain called—I kid you not—the Grimming, the weather went from Loads of Snow to Too Much Snow and offered me a blessed exit ramp from the nursery slopes and my perennially hungover 19-year-old ski instructor. My friends and I huddled together back at the lodge, throwing logs into the only form of heating—a single raging furnace we’d named The Beast—and weighed up our options for things to do at a ski resort that didn’t include skiing in a blizzard. My friend, whose family owned the house, suggested we try out the local spa he’d been to before. We wondered why he was so quick to volunteer for dinner duty instead, but desire for warmth soon overcame intrigue as we trotted off with borrowed swimsuits to poach ourselves in pools of water whilst our friend laughed into his snaps and thawed some sausages on The Beast for our return.

Whatever vision I’d had of a cozy alpine spa retreat quickly evaporated as we pulled up outside something the size and comportment of a department store. This was a serious multi-level bathing complex and it was packed with locals. If we’d taken a beat longer at the reception desk, we would have reckoned with the enormous sign that declared the complex “textile frei” beyond the kids’ paddling pool, but we’d paid our entrance fees and suddenly found ourselves surrounded by hundreds—literally, hundreds—of naked Austrian strangers.

One of our party, an American, was so overwhelmed by what he called “this European obsession with nudity” that he stormed off to the deck chairs outside the cafe and put a towel over his head. The rest of us pushed on, slowly peeling off our layers and keeping our eyes resolutely above the neck as we gingerly headed towards one of 50 or more steam rooms. Before long, the simple fact of our nakedness melted into the background. I guess it’s hard to stay uptight when the environment you’re in is expressly designed to do the opposite. I found myself gazing at naked strangers through the steam in the way you might look at potatoes in the produce aisle—no intention or judgment, just browsing the various lumps and bumps. Most of the men were curiously hairfree below the earlobes, like upright seals in toupees, and their wives and girlfriends wore blue frosted eye shadow and gold jewelry despite the water and the heat and the fact it wasn’t 1982 anymore. Everyone looked like they ate boiled potatoes and pork chops three times a day.

Feeling more confident, and leaving our friend to scrub his mind free of rampant nudity, the three of us girded our loins and explored the deeper environs of the spa complex where the saunas were located. My partner nonchalantly strolled ahead of us into some kind of potting shed, the door of which was firmly slammed in our faces by a towel-clad man with a glistening shoulder-length perm. He was, it transpired, a gus meister—a sadist with control of the thermostat and a penchant for using his towel as a whip. My friend and I peered through the porthole, as my partner was scolded in front of the sweating crowd for letting the heat out. He was now in the hands of a man who looked like he’d eaten Kenny G for breakfast and there was nothing we could do to save him. Less than an hour into our spa experience, and we were two men down.

And so, the two of us left standing headed into the empty sauna next door. It happened to provide a stunning, moonlit view of the snow covered ground and the potting shed where unspeakable things were happening. We gazed out into the starlit night in convivial silence, brows beading with sweat as the sand timer trickled down, grateful to rest our eyes on something that wasn’t flesh. Then the door to the potting shed was flung open, disgorging 20 or so bright pink people whereupon they promptly threw themselves onto the snow-covered ground and started rolling around. “Oh, would you look at that..”, my friend quietly muttered. Oh, would you look, indeed—for there was my partner, resplendent in the full moon as he writhed around naked in the snow with his new friends.

***

Back in Denmark, in early 2016, I had developed a lingering curiosity for the eccentric ritual that was being performed at my local beach. Asking around, I learned that the turquoise pontoon was the location of a longstanding winter bathing club, where members rotated between the frigid sea and pine-clad saunas every day of the week, every week of the year. Applications for this obscure membership were open during the first hour on the first day of October to anyone who could navigate the website that had been built in 1997. Correspondingly, the fee for such a bewildering process was less than 20 cents a day. Somehow, my partner and I signed up. So, too, did friends in the neighbourhood, and so we headed off together for an induction session that was totally in Danish which I totally didn’t speak.

Passing over the little wooden bridge from the beach into the winter bathing club for the very first time is like passing some mythical border where The Emperor’s New Clothes is operating at scale, in that lots of people are naked but no one talks about it. You, the one in the arctic base layers and wind-breaker, start to feel like the weirdo in a land where clothing isn’t part of the religion.

Having run the gauntlet of nudity, we finally huddled together in a cabin and waited for class to begin. It was a brisk reminder that Denmark has a national obsession with rules, and despite the seemingly carefree nature of the activity at hand, there were many, many rules for winter bathing. My friend kindly noted the most important ones down on his phone, in English, and periodically showed them to me. You must enter the water ass first, he revealed at one point. I couldn’t picture the pretzel-like distortions I would have to put my body through to conjure such a feat, but Mamma Gus—the grey-haired matriarch delivering the commandments when she wasn’t whipping people in the sauna—was already onto the next bathing diktat which my friend was frantically transcribing. “Who are these people?” I wondered to myself as I gazed across the packed room, before catching my reflection in the window.

People joked, when I first moved to Denmark, that I had relocated for the weather. Lately, because I am not a fucking lizard, I have come to agree. If I must spend a winter somewhere, as a woman for all seasons, then I’d rather spend it here. From the unencumbered vantage point of where the land meets sea, and the weather plays out on an enormous canvas, you understand that the Danish winter contains multitudes. There are days on the dock when the sky is cerulean blue and you can see your toes through the water as the sun shimmies off the ripples. There are days when the slate-grey sky rains down on the churning waves and you hold on to the ladder for your own dear life. And there are days when the sea freezes over, and they cut a hole in the ice so you can swim through the slush as the snow quietly settles around you.

Cold water immersion, much like the culture around it, is something you acclimate to. What was once an affront to the system—the temperature, the nudity—becomes the norm. I quickly learned the right way to compose myself for winter bathing, ensuring I didn’t squeal when I entered the water, and placed a towel between my butt and the bench of the welcoming sauna. I came to understand that the rules are a necessary part of the ritual, because they hammer out the pointier parts of our personalities and let us live the simple mantra of the seasoned bather: cold, heat, and repeat.

Every week I do this ritual a few times over the course of an hour, and when I am done my skin is buttery, my muscles loosened, and whatever thoughts were raging around my head have floated to the bottom of the sea. In the absence of any kind of spirituality that would find me convening in places of worship, winter bathing is where I go—for solace, for connection, and to grapple with the very meaning of things. I do not know what I did or who I was before I became A Winter Bather. How small my life must have been without this tremendous cracking open and repair. It has become a constant amidst chaos and the answer to my questions.

I have asked it many questions, lately. Last year was bruised by loss—the loss of a job, the loss of a home, and the loss of a much-wanted pregnancy. In the aftermath of the very worst day, when I joined that dreaded clutch of women who go to hospital pregnant and leave without a baby, I longed for the cold water. No swimming, the miscarriage pamphlet had advised, due to the risk of infection. I waited and waited whilst I bled each day, deep red and clotted, unable to fathom the cruelty of the loss as the memories bounced around the lockbox in my mind. I needed an ocean to pour them into.

When the time finally came and the bleeding stopped, it was a quiet weekday afternoon. A couple of lunchtime bathers were already packing up their things, leaving me and a pair of ducks to enjoy the moment in companionable silence. The winter bathing club actually has a name: Det Kolde Gys. It roughly translates as ‘the cold shudder’, which is strangely enigmatic for a language which is so blindingly matter-of-factual. It points to the shared sensation of every single person who heads down the ladder and into the water, no matter how seasoned the bather. Like the rumble of an engine turning over, the cold shudder is the sign of life. That day I welcomed the shock, drawing it deep into my body and wrapping my arms around the pain before I released it into the water. The balm of the heat in the sauna just moments later made me weep. Isak Dineson was right when she said that “the cure for anything is saltwater - sweat, tears or the salt sea.”

Cold, heat, and repeat; winter, spring, summer and autumn. Rituals are how we endure.

0 notes

Text

Our Kaftan Years

As summer finally broke into autumn here in Denmark, I found myself performing the one reliably consistent ritual in my life: getting out my winter knits from storage and packing away my flimsy summer skirts. I have a love-hate relationship with this ritual, so I usually find my way through it by pouring a large glass of wine and popping on some Lizzo to set the scene for what I try and convince myself is a rigorous practice in gratitude.

To do it properly, of course, you have to take every single item of clothing out of your closet and storage boxes before you decide what to hang, what to mend, what to rehome and what to pack away. I am deeply constrained by space, as my closet is about as big as one you’d expect to find in a 90 square meter apartment which is home to two weary adults, one chaotic toddler and an extremely large and self-entitled house cat - which is to say, it’s not very big at all. Once everything is piled up on the bed, I usually have a small existential crisis, as the task seems large and impossible and impossibly large because it’s not just clothes, is it? It’s my whole bloody identity. I might be choosing outfits that are appropriate for the season, but I’m also thinking about who I’m going to be for the next six months. That’s a lot of heavy lifting for a wet Wednesday evening in October.

It’s at this point my husband will wander into the bedroom and make some light hearted observation about “doing a Home Edit” because - god love him - he will just wear the same pair of jeans for 12 months of the year, before beating a path back to the sofa when he sees my rictus grin in response. I make the cardinal sin of trying things on that I haven’t worn for a year which only serves as a miserable reminder of the general trajectory of things (fashion, generally; my body, specifically), and leaves me hot and bothered and ready to set the whole lot alight and be done with it.

As the task plods on and I handover between vests and dresses and linens, and their corresponding cousins of base layers, trousers and woolen knits, I time travel. Back to the fleeting months just gone, and of summers past; back to the moments lived and the moments intended. Clothes are a fantastic reminder of who you set out to be when you first placed those items in your closet, and who you became from the ones you actually wore. Veterans of decluttering, especially clothes, will tell you that you have to be ruthless in the attack. There’s no time for whimsy about that skirt you last wore in the Before Times when you were child free and living off booze and sex as you hustled your way through your early 20s, that is never, bar some divine intervention, ever going to fit you again. Plus you bought it for a tenner when you were hungover one lunchtime and it’s made of so much synthetic fabric that it’s basically plastic and it’s the embodiment of everything that’s wrong with the fast fashion industry and culture in the mid-2000s. So, yeah, get rid.

But also, give yourself a minute to remember the young woman who wore that and had a blast. Because she had no idea, back then, she’d eventually be holding the same skirt in her own home in Copenhagen with her husband sprawled out with the New Yorker and her daughter sleeping soundly next door, even though she dared dreamed of these things.

******

A week or so before The Great Outfit Handover, the three of us went back to the UK to see some friends and family. It included a short trip to Edinburgh to attend a milestone birthday party for a long-loved friend, Kate, which was an inevitable nostalgia-fest given that it was where I’d first met her, whilst studying there at University two decades previously. There’s nothing like wandering around your old student haunts with a toddler in tow to make you feel like a wizened old fool, pointing out the pubs, clubs and house parties you regularly stumbled into or out of, during a glassy-eyed ‘history’ tour.

By the time we all converged for festivities, we were buzzing with memories of people and places and spaces and things that had shaped our onward trajectories. More often than not, many of the stories that made us cackle into our wine glasses that evening centred on the entirely inappropriate or ridiculous things we had worn: the shredded ballet pumps for a hike up Arthur’s Seat; the layers of pashmina we mummified ourselves in during lectures; the second hand ball gowns from legendary thrift-store Armstrongs for our graduation party; the tireless pursuit of elaborate costumes for any excuse to throw or attend a themed party. One of our friends that evening revealed that she was wearing a red mini-dress she had bought whilst we were undergraduate students - we all oo’ed and ahh’ed at the fact it still fit her, both practically and existentially.

There was something about the recall of outfits that cracked open new vantage points into times long gone. I can vividly remember the sequined slippers I wore in the lashing rain as I trudged back from the library after my first set of lectures, or the beloved hip-hugging Diesel jeans I ate only salsa and rice for two weeks so I could afford. I can remember, like it was yesterday, the moment Kate burst into my Disney themed 20th birthday party dressed as Buzz Lightyear, in a costume onesie quite literally intended for a 10 year old. When we talked about our clothes, we were talking about ourselves, in some of the most authentic and open ways possible.

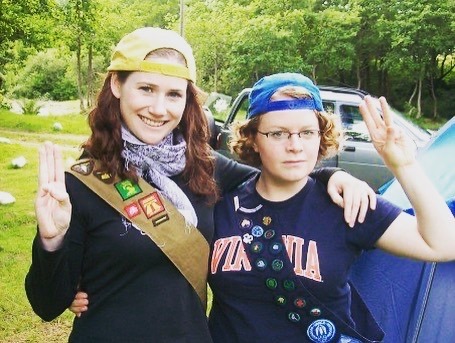

One of my favourite photos of Kate and I is from 2007, when I gatecrashed a Highlands camping trip after my scalding break up from a love affair that had burned too bright and too fast and left me gasping for air. On the flight up from London to Edinburgh, as I wept into my room temperature Chardonnay in a plastic cup, she let me know she’d packed “something special” to set the tone for our hiking weekend. Whilst I admit I had a fleeting vision of being hauled out of arrivals by some diligent drug-sniffing hound, it turned out to be her old Girl Guide uniforms, lovingly packed between her raingear and thermal layers. And she was right: we set up camp dressed as Brownies and Guides, bent double with laughter and so incapacitated with hysterics we couldn’t assemble the tents. When I look at that photo now, I see two young women bedecked in Girl Guiding memorabilia, giving the earnest three-fingered Brownie Honour salute, like an “F-you” to the world. I will always remember the way that Kate stopped me losing all sense of myself in the wake of that ridiculous heartbreak, by intentionally dressing my memories up in joy and laughter instead.

*****

Back at the party, we danced for hours to music of our formative years, feet aching from the effort but hearts ringing out. In a knowing nod to the flimsy footwear of our youth, I’d popped on a pair of ballet pumps. “And now these are our Kaftan Years”, Kate retorted with a throaty laugh, gesturing at her perfect, oversized shift dress. I couldn’t hug her close enough when it was finally time to say goodbye.

And so I paused, during my closet edit, when I pulled out a beautiful blush-coloured silk kaftan, ready to chuck it on the ‘pack away’ pile. It was handmade years ago by a staggeringly talented friend who ran her own design studio in south London. I fingered the worn seams and the faded label, and pulled the silken length through my hands. It is decidedly not appropriate clothing for a Danish winter, and yet I found myself hanging it back in the closet. In that moment, the balance between space and reason tipped in favour of the splash of pink that will remind me each morning, when I throw open the closet door, that the way we do anything is the way we do everything. Including the many glorious moments to come in my Kaftan Years.

0 notes

Text

Sounds like home

The noise outside our apartment is incessant. Drilling, digging, banging, beeping. “BIG DIGGER!” our toddler exclaims, every time we leave the building, as the only one who finds any joy in the construction works which have been taking place for over three months.

Needs must. The council is improving the drainage on our road to account for increasing numbers of cloudbursts in our climate-challenged future. And they’re reducing the number of lanes for cars, whilst maintaining the glorious raised and paved cycle path that means I can bike with my daughter to daycare and not panic about being blindsided by a bendy bus. We’ve even heard a rumour they’ll plant some trees in the midway, giving a more cosmopolitan feel to what has already been euphemistically called a ‘boulevard’. So I guess I can put up with the noise.

But it does set the mind wondering about what it might be like to live outside of the city. My daily life is soundscaped by what amounts to the continuous noises emitted by other people living and doing. We are one of 32 homes in a block of flats totaling over 100 homes arranged around a shared courtyard. I can never not hear the lives of others ricocheting off the walls; the squeals, groans, shouts, coughs and cries of existence bouncing off the brickwork and into my ears. A few weeks ago, my husband and I lay in bed at midnight, staring at the ceiling in the blue moonlight and cursing the asshole who decided to throw a party and leave their windows open. “We have to MOOOOOOVE”, I stage-whispered, frenzied by the need to sleep. When the music finally fell silent, our cat shuffled into life and started yowling for breakfast around 3am, followed by the dawn chorus of our daughter who believes it’s acceptable to wake her parents at 4:30am to ask for raisins. Soon the water pipes that rise up through every apartment were groaning and hissing into life, as people traipsed to the shower and put the kettle on. And before we knew it, the drilling, digging, banging and beeping began. And on it goes.

In 2006, I lived in New York for a stint. My first night in Hell’s Kitchen, propped up on an inflatable mattress in my friend’s studio apartment, was like trying to sleep during a Fast & Furious screening. Constant police sirens, every neighbourhood bar with its doors flung open, more than two people having a conversation… New York streetlife is expansive and vibrating with noise, every single minute of the day. It truly is the city that never sleeps, because who the hell can with all that racket going on? During that winter, there was a major snowfall that ground everything to a halt. Trains were canceled, roads were closed, people lost power and water for days - it was hard and sad, sure, but I just remember the silence. I padded out in my most sensible shoes and walked 25 blocks to the MoMA (defiantly open, despite the weather), listening to my breathing in a city that had finally been muffled by a thick, white blanket of snow.

I’ve lived in all kinds of homes, in all kinds of places, but I’ve never lived in the countryside. The closest I’ve come is the house my parents rented when we moved to the East Midlands, which sat on the very edge of a suburban housing estate and was flanked on the back by fields. It wasn’t unusual to find a cow trapped in our hedge, eating her way into our garden, but I never thought of it as ‘the country’. The lights of the nearby city were too bright, and the buses and cars that trundled down the main road were confirmation that the urban sprawl had us in its clutches. Even in the suburbs, other people living and doing is always in earshot; or, as my husband says, suburbia is defined by whether you can hear a lawn mower running on a summer’s day.

But this summer, we decamped to a house in the Danish countryside for a two week holiday - something we had talked about for years, but never pulled the trigger on until now. There was an unspoken agreement that we were tired of the city - tired of the soundscape - and needed a break so we could hear ourselves think. So we found a house in the middle of nowhere, about two hours and many, many country lanes away from Copenhagen, and ventured forth. It was the most middle-aged decision we have probably ever made.

The thing I quickly realised about the countryside is that it’s not actually quiet – it’s filled with noise. Most of these noises are things I’ve not heard before, like birdsong, and some are without evident source and chill your blood in the middle of the night. Digging, drilling, banging, beeping - you know where you stand with a big digger and an overweight construction worker. But scratching, shuffling, pecking, howling…? No thanks. Some might claim this is Mother Nature’s embrace, but I got the distinct impression that she wanted me gone and was releasing an army of creatures that don’t see the light of day in the city.

I couldn’t move for spiders, for a start, and as a lifelong arachnophobic I was faced with the daily gauntlet of undertaking basic tasks whilst being watched through multiple sets of eight eyes. There was one bird which had taken residence in the garden that let out a cry resembling a squeaky toy, and another that informed everyone the sun had risen by doing a perfect impression of Janice from Friends: “Ahhhhh-uh-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ahh”. The wasps and bees I could just about handle, but it took a Herculean effort to casually brush away the potato-sized hornet that landed on my husband’s back without alarming my daughter. If fear is contagious, then I felt toxic by that point.

Even when we sat indoors, with the windows closed against the advancing hoards of wildlife, it was never truly still. The ever-present flies smashed themselves against walls and doors as they endlessly worked their way throughout the house, sending my husband into a murderous rage with a fly swatter each evening. And one night we witnessed a biblical thunderstorm that suddenly bathed the bedroom in silky white light as the rain smashed down through the trees.

We spent most of our days driving away from the house to other places in the countryside or on the coast, craving a little civilisation other than the nearest supermarket. Whatever flirtation I had with being a country bumpkin was gone within days, as I realised that the sounds of living and doing in cities were the very reason I live and do in the city in the first place. Even when I went for a run, and witnessed two enormous nutbrown hares and a deer bound right past me, I had Lizzo blaring away in my ears. You can take the girl outta the city, etc etc.

We returned to Copenhagen with a camera roll full of memories and an urgent need to hit up our favourite cafe for coffee and baked goods. I walked with my daughter down the highstreet, smiling inanely at the various window displays and signage like I was on day release from residential care. The barista at the cafe met me with a big grin, and remarked that she hadn’t seen us in a while. “We’ve been away for two weeks but it feels like two years”, I replied with a sigh, unaware of the truth until it left my lips. It was the longest I had been away from Copenhagen in over seven years.

The profound irony is that summer is the best time to be in Copenhagen if you’re looking for a little peace and quiet, because the city empties out when every Danish family makes their annual pilgrimage to their summer house. More often than not, construction works are put on pause and plenty of local shops and restaurants shutter up for a wee break. In these passing silences, you become more aware of the absence of presence, or the presence of absence perhaps. And for almost four decades, I’ve lived a life in earshot of the presence of so many other lives that their absence feels like part of my home is missing.

The next morning, we awoke to the creak of the floorboards as our daughter made her way to our bedroom to put in some insane pre-dawn request, which our cat took as her cue to start smashing the blind against the window in disgust at our failure to put her food out. Before long, the water pipes started up their music, and I listened to our neighbour chatting with his kids over the bathroom sink. Soon the diggers would arrive, much to the delight of my daughter, and breakfast would be accompanied by the dulcet tones of a pneumatic drill.

It’s so good to be back home.

0 notes

Text

Where do you become from?

There’s an evocative line in a Rebecca Solnit essay, called Abandon, where she talks about a childhood friendship that burns bright and fast:

“Perhaps rather than describe her as three characteristics, I could describe her as three places: the suburbs that made us and that we scorned and fled, the urban night she made into a home of sorts, and the pastoral world of a lyrical European culture and maybe of the hills past our childhood back yards.”

There are also a few banging lines in an old J-Lo song, in which she declares: “Don't be fooled by the rocks that I got / I'm still, I'm still Jenny from the block / Used to have a little, now I have a lot / No matter where I go, I know where I came from…”

Different audiences, perhaps (with me, lurking in the middle of that improbable Venn), but both these commentaries perfectly capture that identity-morphing role that place comes to bear in our lives, to the extent that where we live and have lived, is so deeply baked into our sense of self that you cannot pull them apart––much like the impossibility of removing the eggs or sugar from a cake. Place, space, people and things: these are the common denominators of how we make a home, but I have also come to see that they are how we make ourselves.

A few years ago, a colleague in my team ran a get-to-know you exercise which required us to draw five things that would explain who we were. Like Solnit’s proposition, three of my five things were landmarks: the Brooklyn Bridge, a saguaro cactus native to Arizona, and a Danish bike path. It turned out that the best way to explain who I was, was to talk about where I had lived. When I think about placemaking in this way, as an act of becoming, it resembles some kind of personality scavenger hunt. It’s as if parts of my identity were left in unfathomable places and I had to nose them out like a truffle pig. Knocking on 40, I don’t even know how far along the trail I am.

Maybe that’s why I struggle to answer the dinner party conversational gambit of “where do you come from?” As a white, middle class woman, I don’t have to reckon with that question from a perspective of ethnicity as many do, noting the silent emphasis contained within (where do you really come from), that’s both ignorant and exhausting. In my case, people throw it into conversation because they’ve got nothing more imaginative to ask. On this point alone, I defer to the great David Sedaris who likes to pose unreasonably brilliant questions to his fans during book signings. “When was the last time you touched a monkey?”, for example, is a masterpiece in form and function, and we’d all do well to follow his lead. Anyway, I digress. The point is that asking someone where they are from is, quite simply, a crap question to which most people have inadequate and boring answers. But ask someone to tell you about a place that made them who they are… Now we’re getting somewhere.

When a place means something to us, it’s because it feels like home. Years ago, when I first moved to Copenhagen, I went to a talk by a handful of creative immigrants to Denmark who shared their experience of being artists with an outsider’s perspective. Two of the speakers were sisters, Seda and Şeyda Özçetin, who had moved to Copenhagen from Turkey with their mother, Hamide, in 2011. They held degrees in visual culture and industrial design, and had started a consultancy which gave them an opportunity to flex their creative muscles whilst pushing on an activism agenda around inclusion and identity. They talked about place and displacement, of being outsiders within. But it was the t-shirts they wore that bore the slogan “I am feel from Copenhagen”, with their intentional strikethrough, which really stood out to me. There was a lot of sadness in their story - the agonising process of getting visas, and the death of their mother from a degenerative illness - but it struck me that placemaking was their emotional anchor, and the feeling of home was central to their becoming. I feel, therefore I am. Or something.

I, too, feel from Copenhagen. And I feel from New York City, and Phoenix, and Edinburgh, and London, and Salisbury, and Derby––places where I clutched keys to front doors that were fleetingly or lingeringly mine. But I also feel from a campsite in Normandy where I holidayed with my family year after year as a kid, and a pub on Great Queens Street where I went on the first date with my now husband, and the park next to the hospital whilst I was in labour with my daughter… It’s all baked in and I can’t pull it apart. I don’t know if I am who I am because of the places I’ve been, or I chose the places to go because of who I was becoming. Perhaps it doesn’t matter… The cake still comes out of the oven whole at some point.

I hadn’t thought about the Özçetin sisters in a long time, so I looked them up online, to see how things were going for their creative ventures. I realised that, in a city of around one million people, they’re now based just three houses down from me. It’s funny how placemaking shows up like that, cutting straight across different lives like a tram line, and connecting us all when we might share nothing else in common. We’ve come from such different places, but now we all look out onto the same maddening construction works that have been tearing up the road for the last two months, and the man who hangs his laundry, naked, on his balcony, and the fluffy white dog who routinely stops outside the pub during its daily constitutional for a pat on the head from the regulars. Just like us, this little block contains multitudes.

So the more interesting question to ask is not where someone comes from, but where they become from. A few glasses in at my fantasy dinner party, I reckon Lopez and Solnit would have plenty to say on that.

0 notes

Text

The cold shock

As Copenhagen finally shifted into what the Danes wearily refer to as Green Winter, the last weeks have been peppered with those cerulean blue skies that make you forgive all the misgivings of the slate grey months just passed and remember why you chose to live here anyway because it sure as shit wasn’t for the weather.

On these kinds of days, Copenhagen can do no wrong in my eyes. I am heady with the blush of first love in the Springtime, looking for any opportunity to bike over bridges and through parks as the trees bulge with blossom and the light shimmers off the water. When Copenhagen comes back to life, so do I.

After I had spent a lot of time thinking, and writing, about space, I started thinking about rituals. Like everything else at home, these two things often intersect as spaces become places where rituals unfurl, and rituals themselves often determine the intention of the space at hand. I was prompted, no doubt, by the handover from Winter to Spring as I found myself performing one of the first rituals of the new season: packing away my winter coats in the basement. It’s a ritual enforced by the lack of space in our closet, but it has the unintended consequence of making me take stock - not just of the items in my wardrobe, but of myself. Not to get all ‘wooh’ about it, but sometimes I’ll whisper a wee thank you to the coats in question for getting me through another one. We did it, lads; it’s jacket season now.

Maybe another way of talking about rituals is traditions, and I reach for those too. Having a child makes me reflect harder on how we mark moments like birthdays and holidays, because I can think of nothing sadder than an adult who has no formative memories of what their family did or didn’t do to honour, celebrate and generally give reason for joy and connection. Ritual and tradition is repetition - between a family, throughout a community, across the years, spanning generations. As Easter rolled around for the third time as a constellation of three in our small atheist household, I suddenly realised I needed to think about this properly. What Easter rituals did I want to carry over from my lapsed-Catholic-skewed-Christian-madly-artistic childhood into this hatchling of a family my husband and I were nurturing for ourselves? And how did we want to blend the things we were familiar with from the UK, with the local flavours and quirks of Denmark? Tradition can appear like the lazy option - it takes guts to break out of the mold - but I’m finally understanding how much work tradition takes to build and maintain. In the end, we introduced our toddler to the Easter Bunny as a distributor of her favourite craft materials, and headed to a restaurant for a classic Danish lunch. In our new rituals, I guess we also get to choose when two frazzled parents with full time jobs get to outsource the cooking and cleaning for once.

Through the research we’ve been doing at IKEA, we can plot a neat line between the rituals we perform and our mental wellbeing. Most people don’t actually talk about ‘rituals’, we tend to talk about hobbies or personal projects, but what’s underneath them all is a sense of intention. It’s not a ritual when you drop your kid off at school at the same time, stop working for lunch at midday, and start cooking dinner at 6pm - that’s just routine. It’s a ritual when you intend it to be something that’s more meaningful for you. Sometimes people build rituals around tasks, but I just can’t shake this feeling that it’s a symptom of the way performance culture has spilled into everyday living. Why read a book when you can listen to it at twice the speed on audio? Why go for a walk during the day when you can get up at 4am and do two hours of body conditioning before your first meeting? It all just makes me want to lie down in a dark room. Rituals aren’t about getting things done, but the very nature of the doing. They demand time or patience we don’t believe we have.

In my home, we have a ritual of making pizzas from scratch on Saturday evenings with our increasingly strong-willed toddler. Let me gently inform you that this is the most inefficient and deeply stressful way to make pizza unless you like red sauce all over the floor and the majority of toppings in your child’s mouth before they make it to the oven. I am literally sweating by the time we sit down to eat; there are so many easier ways to make dinner. But we don’t do it because we want to eat pizza, we do it because we want to give our daughter the opportunity to learn how food is made, and for us to come together as a family to prepare a meal.

A few weeks ago, my colleague and I shared some of the findings from our most recent research into the connection between mental wellbeing and life at home during an internal event for a company-wide Health Week. It came the day before I was due to take 10 days off for what I was calling a ‘wellbeing break’ - something that precedes the more defining request for sick leave. Burn out, exhaustion, stress… These are all actually different things, but we tend to use them interchangeably to express what many of us are experiencing: an inability to touch the edges of ourselves any more; a feeling of being marooned within your own body and mind, unsure how to proceed. My tipping point was a culmination of demands my personal and professional lives placed on me, layering one on top of the other like material strata, hardening under pressure. And then I snapped, in front of my child, and knew that something had to change immediately or I would shatter completely. Faced with this reality, I understood that the best way back to myself was through a tried-and-tested ritual. One that I had increasingly failed to make the time for as the tasks gnawed away at my waking hours, month after month. One that was only for me.

Let me state here, very clearly, that I’m extraordinarily lucky to have the tools and resources to put my health first, not least the simple fact of living in a country with a gold-standard social welfare system. I take none of this for granted. But I also live in a country where an alarming number of people take all their clothes off and swim in the sea 12 months of the year. Reader, I am one of those people.

Living in the UK, I would have scoffed at this proposition - Nudity? In public? In the winter? - but here we are and here I am, gladly stripping in a wooden cabin and gliding into water colder than the base temperature of my fridge. The upside is that as soon as I get out, I scuttle over to a sauna and sweat away for 15 minutes.

I have been during the coldest winters, when they have to cut a hole in the ice to let you in; during autumn’s sideways wind and rain when the sea churns like grey porridge and you can’t hear yourself shout; and when those spring and summer blue skies open up above mirror-still waters and you can see your toes all the way down on the sandy floor. This ritual is all the sweeter because of how much it differs, season to season, come rain or shine, with the same guaranteed result. It teaches me patience and gratitude; it fosters resilience and balance.

On the first day of my break, I packed my towel and set off to the jetty by the beach when I would ordinarily be opening up my emails. It was sunny and still, and the water temperature hovered around 8 degrees; a perfect day for bathing. There were only a handful of other people using the facilities that morning, all of us nodding a small smile to each other as we quietly undressed. Denuded, I wrapped my towel around me and walked out onto the chilled wooden decking, inhaling deeply after months of anxiety-addled shallow breathing. And so it began.

A hearty share of the benefit of any ritual comes from implicitly knowing the sequence of things that happen so you don’t have to think about it - this, then that, and that. Sea, then sauna, and repeat. My mind emptied out as my body moved from sea to sauna, idly watching the returning swallows skim the surface of the water and chatter to each other. I started to feel the outer edges of myself again. It was going to be ok.

I began writing this piece whilst I was babysitting for dear friends, propped up on their sofa that faces out towards the incredible harbour skyline in central Copenhagen. I’m finishing it in a cafe just down the road from where I go winter bathing. In the weeks in between, I’ve consistently carved out time for my ritual and I am all the better for it. So much so that I packed a towel in my work bag – just as soon as I’ve dropped the final full stop of this essay, you’ll find me out on the jetty. Right here.

0 notes

Text

Feeling our way through the space around us

I have spent the best part of two years trying to write a story about space. Not the inky starlit, final frontier kind, but the more earthbound variety that relates to the areas around things which exist. Like, the amount of space for new books on my shelves, or whether I can fit another suitcase filled with crap under my bed, or where to go that’s far away enough from my family when I need to have a midweek existential breakdown.

I wanted to write about space for the seemingly innocuous reason that it’s one of the four dimensions of home, along with place, things and relationships. And so, I have written (and rewritten) thousands - literally thousands - of words in the slivers of time I can find around other kinds of things which exist, like my job and my demanding toddler and my unquenched thirst for reruns of early 2000s sitcoms. But it’s just… garbled nonsense. It’s free range prose that uses a lot of words to say little more than nothing at all. I cannot, for the love of anything in my life, bring this particular piece of writing home.

During the same period, I have written about different topics that are, on the face of it, much harder and sharper. The complicated birth of my daughter; becoming a parent during a pandemic; losing a dear friend to brain cancer; the scalding experience of asking 30 colleagues to tell me how I could be a better person (don’t ask). Which is just to say, I’m not shy about writing my way through difficult feelings. Hell, writing my way through difficult feelings is how I process them to begin with.

So it struck me, after two years of stop-start rewrites and admonishing myself for being a staggeringly shit writer, that maybe there is nothing innocuous about how much space you have at home. That maybe I was nowhere near done with writing my way through my feelings, because the way through was a lot deeper and further than I could have possibly anticipated. That maybe I couldn’t find the words without reckoning with some of the most intensely painful feelings we flawed little humans are capable of holding: humiliation, embarrassment, guilt and shame.

Let me try to explain. One of the things about writing about life at home is that you take a lot of staggered walks through the past. When the words fail me, I often find myself on Google maps trying to relocate my bearings in old neighbourhoods, stepping around redirected roads and new buildings. Before I know it, I’m down on street view, standing outside a grainy image of a house I haven’t been to in decades. It was one of those internet-enabled ambles a few months ago that found me on Rollestone Street - a terraced road just outside the centre of a historic cathedral city in the south of England. The front door was a different colour and the brickwork had been repointed, but there she was – a classic two-by-two house, all snuggled up next to her neighbours like a row of crooked teeth. This was where I lived for the best part of my childhood, and it has shaped the way I have made a home for myself ever since.

I guess it was nostalgia that hit me first, in the original sense of it being both a longing and a sickness. For all the work I do trying to make coherent what we mean when we talk about the feeling of home, I was left grasping for words to describe the soupy mix of emotions I had for the space behind this particular front door. Looking at it from the comfort of my living room many, many miles away, I suddenly felt desperately sad about how small the house was. And I could remember it then, vividly. From wall to wall, the house was roughly the same width as a generous three-person sofa. In fact, when visitors came, you could shake their hands at the front door whilst sitting on ours. The downstairs was bisected by an open wooden staircase that rose sharply from the ground floor to the first, and ended in an abrupt T where you headed right, directly into my parents’ bedroom, or left towards the bathroom. My parents had turned the upstairs hallway into a studio where they both chipped away at their work, painting and writing. I slept in the renovated attic, under the eaves of the roof, with my little sister; and what amounted to a backyard was a six-square-metre slab of concrete flanked by walls that obstructed the view (but sadly not the sound) of the mechanics to the right of us. It didn’t really matter, because most of the space was taken up by the old shithouse that pre-dated our indoor bathroom and was now filled with rusted bikes and extremely confident spiders.

My parents took to constrained living with creative relish. They compensated for the lack of a standing shower by turning the bathtub into an Egyptian sarcophagus, and painting the bathroom walls like the interior of a tomb in the Valley of the Kings. They lined our personal Shawshank courtyard with buckets of flowers and trellises of tomato plants and runner beans. Sheets of wood were hauled out of skips and turned into bookshelves that ran the entire length of the house, and all the walls were hand painted with murals or motifs, including the beautiful lark-filled sunrise that rose from floor to ceiling in my bedroom. The tools of my parents’ trades filled every surface, and we’d have to move manuscripts, puppets or papier-mache Roman helmets out of the way for mealtimes.

Saturdays were for grocery shopping at the market, and cleaning. Once we’d hauled our misshapen fruit and vegetables back from town (“A crate of cauliflower for a quid!”), my parents would put on a series of vinyls - Lynrd Skynrd, The Beatles, Aretha Franklin, The Beach Boys - and drag the vacuum cleaner around whilst my sister and I performed karaoke theatrics and jumped off the furniture. At some point my father would rustle up a pan of something delicious for lunch, usually involving bacon and beans, and we’d head to our habitual seats at the table to receive steaming plates of food and hunks of bread through a yellowing formica screen that opened out from the cramped kitchen counter.

There was colour and clutter, and laughter and tears, and calm and chaos, and food and music, and living and dreaming, and… somehow there was room for it all in this tiny little house.

My school friends did not live in homes that looked like this. Their kitchens flaunted islands and there were whole rooms dedicated to play. They didn’t bathe under the gaze of Egyptian gods or pass meals through a hole in the wall. My best friend, a tall and exquisitely beautiful girl called Natasha, lived in one of these disarmingly large and rambling houses. She had three boisterous brothers who drew their mother to increasing levels of distraction, so we’d hide away in her bedroom to reenact the entirety of Grease or play back-to-back games of Monopoly. Come snack time, we’d head downstairs to the large, convivial kitchen where her mother would offer up racks of buttery toast and homemade marmalade from the pantry. There was so much space to leisurely squander away hours of our life without getting under anyone’s feet; to luxuriate in leaving board games half-played on the floor. We never talked about it, but I understood that it was just different back at mine.

Growing up, I was an exceedingly shy and sensitive child. I picked up on people’s moods like vibrations underfoot, always alert to the quick glances between adults and the thickening air that seemed to predicate an emotional storm. We didn’t talk about money, but there was often this low thrumming feeling around Christmas, birthdays and holidays. From where I was standing, wealth looked like everything was on steroids - bigger houses, bigger cars, bigger TV, bigger allowance - whereas we seemed to contort ourselves in almost comically-small ways, like a troop of exasperated clowns. Even when we went camping for our summer holidays, under the slate grey skies of Normandy, we managed to squeeze four of us into a two-man tent.

So I can’t really remember a time when I didn’t feel that my home was small, but I can recall quite precisely the moment I saw it diminished through the eyes of another person for the first time. I’d gone window shopping with a new friend, Hayley, and when we called it a day she nonchalantly suggested we walk back the same way so she could see my place. Something caught in my throat, and I tried to brush her off with a range of unlikely excuses. “My sister has this rare chemical imbalance which means she can’t meet new people”, I lied through my teeth, but she was having none of it. By the time we turned the corner, I was so distracted that I was walking out in front of cars. My father opened the door - Good Vibrations was blasting on the stereo, whilst my mother’s on-the-turn cauliflower daal was brewing in the kitchen - and I saw it, then. Hayley’s eyes widened, adjusting to the gloom as she scanned my home from the doorway, flicking between the sofa and the stairs and the table. The practised grin, as she turned to me to say goodbye. The almost imperceptible head tilt that signaled pity; is that all there is? Without crossing the threshold, she had seen enough.

I felt it all, then: embarrassment, humiliation, guilt, shame. The sense that I wasn’t good enough or worthy enough for more. It wasn’t just my home that felt small; now I did too. These feelings continue to resonate through my life, many decades later, like an emotional echo. In some kind of cosmic mirroring, where I live today measures - step for step - exactly the same square footage as that house on Rollestone Street. And there’s colour and clutter, and laughter and tears, and living and dreaming, and somehow room for it all over here too. Until one day there isn’t. But rather than seeing that tipping point as a problem to which there are practical solutions, I find myself disarmed by feelings calling back from my past. It’s really hard to shop for storage solutions when you feel like your tiny closet is actually a damning critique of your background and identity.

So I come here to tell you the one thing I have finally understood after two years of rewriting thousands of words of garbage: space is not a functional issue, it’s an emotional one. If (like me) you find yourself in the market for more space, no matter if it’s a bigger wardrobe or a bigger house, you might also want to give yourself a moment to tune into how you feel. Because it’s not just about finding the space around you, but feeling your way through it too.

0 notes

Text

Up Where We Belong

In a fit of civic duty a few years ago, I briefly joined the housing association that runs the building I live in. It wasn’t something I’d planned to do, but a week before the ballot my neighbour begged me to stand because she needed enough people on the committee to keep a hard-fought roofing project on track. My primary–indeed, only–qualification for the role was that I possessed a pulse. My election campaign was short and sharp—I gave a one minute stump speech at the AGM in halting and woefully accented Danish, over flat cokes and sticky tables in a room at the back of the local pub, which received precisely one clap of applause. It was to everyone’s surprise that I got voted in.

One of the things that fell to the association was the matter of balconies. To put the Danish obsession with balconies into context, you should know that one of the candidates running in the recent municipal election ran a single-issue campaign that demanded “More balconies in Copenhagen”. And he wasn’t even considered a kook. In fact, balconies became so demanding an issue for my building in particular, that soon there was a dedicated Balcony Committee spun out of the housing association. It wasn’t long before it took on a life of its own.

I’ve tried to wrap my head about this national fervour for what amounts to roughly two square metres of additional space lashed to the outside of your flat. Copenhagen boasts some of the most generously sized apartments in Europe, many of them in historic and gently worn brick buildings with original wooden floors, sculpted cornice and great insulation. There is also a strong precedence for shared, green courtyards behind every apartment block, which act like urban oases for city dwellers who need only trot down the backstairs for a taste of garden living. What could a balcony give you that you couldn’t already get where you lived?

And yet, Copenhagen is addled with balconies, like a rash of acne. Small ones, big ones; metal ones; glass ones. On new buildings and old; on streets and estates. Overlooking motorways and walkways and bikeways and waterways. Some get the bake-me-alive broiling heat of the midday sun; others the golden rays of a late summer afternoon; and others still that find themselves on the wrong side of everything, perpetually cast into shadow. They are so ubiquitous that people give you that sad tilt of the head when they realise you don’t have one.

Soon the question came to me: did we want to buy a balcony for our apartment? By this point, we had been bombarded with what felt like propaganda for some Deep State Sundeck programme, but was actually the output of a slightly unhinged resident with access to a colour printer. “WHAT IS YOUR DREAM BALCONY?” the materials yelled above images of gravity-defying structures, ranging from glass and steel obtrusions, to what looked like the location for a highschool performance of Romeo and Juliet. It was probably at this point that I realised the dream of the balcony was way beyond the reality for the clutch of misfits responsible for managing our building, of which I was one. Plus, we had leaks in the 100-year old roof and rats in the basement to deal with. The question was answered for me.

When I walk around the city these days, I often look up at people’s balconies hoping to get a glimpse of the lives up there. More often than not, they’re empty of people; the winters are relentlessly wet, and when the warm weather hits most Danes head to the beaches or parks to lounge like lizards in the sun. I’d like to think that if I had a balcony, I’d eat al fresco every day, huddled under blankets with hot coffee in the autumn and pouring chilled rose in the spring, but the reality is that those extra two square metres would become an awfully tempting dumping ground for the crap I don’t want to look at every day. From where I’m standing, this is what the majority of balconies have become—repositories for piles of stuff, like stratas of everyday life through the seasons and years. The outgrown kid’s bike, the once-used camping equipment, the sad and deflated beach balls. It strikes me that the national obsession with balconies is actually a deeper problem with stuff and the persistent question of where to put it.

There is one balcony in Copenhagen that makes my heart skip every time I cast my eyes up. Located on the top floor of a six-storey apartment block, it overlooks the leafy walkways of the old city walls that curve round a little reservoir just north of where I live. It’s all brick and plasterwork—classy but not showy—and just right for the period of the building. In the summer, there are buckets of red flowers and linens on the table; in the winter, fairy lights and lanterns. The last time I walked past with my husband, as autumn tipped into winter, I looked up to see a woman clutching her enormous Ragdoll cat as she was pulling off her sheets from a drying rack. She saw us and waved—once with her hand, and again with the cat’s paw. We smiled, gazing up from the walkway, and paused for just a moment to let the fantasy of getting a balcony settle around us for size. And then she turned, and went back inside, closing the door behind her as we pushed off again. She had linens to fold and cats to feed, and we had rats to remove from the basement so we had somewhere to store all our piles of stuff.

0 notes

Text

Wanted: A New Life For An Old Home

I’m looking for a new home. It feels like such a loaded thing to say. So many inevitable questions about why and where and how. Because we all know that it’s not just a new home, it’s a new life.

Looking for a new home is a feeling before it’s an act. The actual exchange of contracts and keys and packing up boxes with your long-loved crap isn’t really the part that signifies the moving, because the movement began months, even years, before. It started when the regular ebb and flow of emotions that create the feeling of home pulled back too far one day. Too far for paint jobs and a new coffee table to push the tide in again.

Sometimes it comes out of nowhere; we need to get out of here, chimes the internal memo at 3am. Like when I was 23 and living with my boyfriend of more than four years and suddenly found myself browsing Gumtree for single rooms when he’d gone out one evening. My internet tabs would have told you my relationship was broken beyond repair before I’d said the words out loud.

Sometimes we see it coming up the road, a little way off, lugging all its baggage. We hold the door open for it, knowing that the move is inevitable—we’re facing a new job, a fixed-term lease, a new family member, a live-in friendship past its best. So much of my twenties was spent anticipating the next move, as surely as the changing seasons.

And sometimes we go looking, throwing our doors wide open so we can see out as far as possible whilst those fresh breezes of chance and opportunity dance with the curtains. That’s how I ended up moving from London to Copenhagen.

We feel the expansion and contraction of our new life at home before we’re even in it. Like a phantom resident in a place that gives you one more bedroom, a shorter commute, or a garden to tend to at last. We imagine where we could live because it helps us imagine who we could be.

So, I’m looking for a new home. I’ve seen it coming up the road for a while now, but it picked up pace when the combination of remote working during a pandemic with a growing family in a two bedroom apartment started to feel… unmanageable.

We just need one more room, I’ll say, with a rehearsed laugh about my toddler’s cameos on my work calls, when really I’m screaming inside.

I want to be able to close a door between my family and my job, but I also want so much more. The promise of a new home taps into something deeper than a change of scene; if offers a change of identity. That’s why people’s ears prick up when you tell them you’re moving. They ask where you’re going but they really want to know who you’re becoming.

Imaginary Katie takes herself off to a mash-up of fantasy houses nabbed from the interiors of glossy magazines and reality TV shows, where she throws boho summer dinner parties on the terrace and hosts all of her friends and family in her many guestrooms for Christmas.

Actual Katie scours the slim pickings on the local listings site within her cash-strapped budget, bundles her willful toddler onto the bus to go to a house viewing in a neighbourhood she doesn’t know, and politely shuffles across mothworn carpets in miserable homes that ask for too much and give very little.

It has one more room, I’ll say to anyone who asks.

But there’s no space for the rest, I’ll tell myself.

Recently, I met an estate agent called Søren who showed me around a sad gray house that sat at the meeting point of two major roads running in and out of Copenhagen. It was cold and damp outside, and all the trees were stripped back for winter. Inside, the bare white walls pulled any residual warmth out of the rooms, leaving a lingering sense of hard conversations around the dining table.

How long have you been looking? he asked.

We’ve just started, I deflected.

He peppered me with questions intended for the active home-hunter—that shorthand for budgets and room counts and postcodes that you reel off when you’re in the game and want to win. I was already too tired to play. I absent-mindedly opened and closed doors to bedrooms, toilets and kitchen cabinets, and listened to the muffled roar of the cars outside. I thought about the work we’d need to do on renovating, where our sofa would go in the living room, and what it would be like making pizza with our daughter in the kitchen. I thought about what kind of person I would become if I lived in this house. It did not, as the parlance goes, spark any joy.

I’ve been selling homes for over 30 years, so this is my calling, Søren said. If you want my advice, you should look closer to the airport so you get more for your money.

I thanked him for his time, politely took the sales pack I would immediately discard because I’m too pathetic to be honest, and went for the door.

Sure, I smiled, and headed out. I wish it were that simple.