Text

Lets Talk Lake Towns

What I find most interesting is thinking about the culture and mythos that may have surrounded water and lakes within this culture. Clearly, it held some personal significance if they chose to return after each threat ceased, no doubt knowing another was to come. If they were able to survive away from this landscape then they did not need to return to the lake areas, yet perhaps there was a value for tradition or familiarity within this community. It is an interesting contrast with the logical and pragmatic planning they carried out in response to what seems to be more sentimental or emotional feelings towards lake habitation.

0 notes

Text

Change, Place, and Choice (The Shire vs Lake-town)

As we all know, the Shire seems to pride itself on its almost permanent state of stillness both in form and ideas. We hear no reports of natural disasters, immigration, trade, or any such progress as might be expected of a place still containing living inhabitants. In contrast, Lake-town not only reportedly experiences multiple earthquakes and near catastrophic rains, but uses these natural events to fuel its ability to interact with the outside world. Their swollen rivers merely become quicker roads for the local elves to travel to trade and attend Lake-town banquets. Lake-town seems to pursue interaction with other peoples in the same way the Shire avoids it. I can only speculate that this is perhaps due to the fact that the people of Lake-town were given no choice due the the rule of the dwarves above. Clearly, the role that choice plays in carving out a cultural and national identity cannot be understated.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to put an entire thesis into one word

The Fisher text is in no way light and casual reading, but this is only due to the fact that there are so many complex connections to be made between Tolkien's word choice and the many languages he pulled from. From Hungarian to Finnish to Old English, there is no shortage of analysis and linguistic knowledge needed to truly understand each and every word placed into Tolkien's world. What I find most interesting is that Tolkien knew exactly which words he wanted to emphasize both around and within his places and ideas. For example, the depth of Mirkwood's meaning involves multiple layers of languages speaking about spiders, poison, and darkness. Yet he could have very easily chosen old words that meant a bad end, danger, being lost, or sleep- all valid choices given the make-up of Mirkwood. But the words actually used seem to better describe the overall events and conflicts that arise in Mirkwood. Thus, using spiders, poison, and darkness feels less like a poetic choice and more like an academic's. His meanings not only add depth to his world but also function as a thesis of what will occur in said place. Readers truely get increased rewards as they put in more work and research to understand Tolkien's works!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decapitating Spider Gods and Fly Tattoos

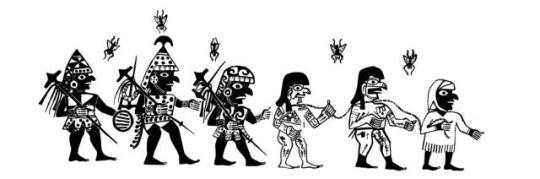

You might not think about the Moche of Peru when you read the Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings, but I do, especially when I get to sections about underground lairs and spiders. The Mochica culture of Peru (100 to 700 AD) had a central god who was depicted as a gigantic spider figure ready to suck the life-blood from his victims. Sometimes he is also depicted with the heads of sacrificed humans in his hands, which is why he is known as the decapitator god. We know that human sacrifices sometimes did occur in this society, usually of prisoners of war, but also sometimes of locals. One such moment is supported by archaeological evidence from the Huaca de la Luna where skeletons of 40 men under 30 years of age show evidence that they were mutilated and thrown from the top of the pyramid. Skulls were brutally severed from the bodies. You can see what that Moche god looked like here:

Seems like a pretty nice guy to hang out with in an underground temple tunnel, which is where this depiction was found. This site is exceptional too, because it housed the burial of a female leader in a society that was pretty intolerant to female leadership (women followed powerful men into death). She is known and the Lady of Cao and she was in her 20s when she died. She was also heavily tattooed with spiders, snakes, crabs, catfish, and even a supernatural being which the archaeologists call the Moon Animal which you can see here:

John Verano of Tulane University, who excavated the mummy with El Brujo Project and Museum director Régulo Franco say that “spiders are associated with rain, as well as with human sacrifice and death, and the serpent is an important element associated in many ancient Andean cultures with deities, fertility, and human sacrifice as well.” So if she was a queen, it seems she was heavily identified with the sacrifice of humans.

Death masks show us that some shamans and leaders would have tattoos on their faces of animals or beings that they identified with or could perhaps “shape-shift” into during trances. The death mask below, also from the Moche culture, shows a heavily tattooed face with a fly necklace around the upper neck as seen here:

Huchet and Greenburg (2010) argue that “the Moche deliberately exposed the body to the flies with the hope that the anima or spirit of the deceased would be carried from the maggots into adult flies and through close contact with people, complete the human cycle.”

Here we can see little fly gods waiting in anticipation as they hover over Moche warriors and prisoners alike. They do not discriminate when they release souls.

All this is what I think about when I read, “There agelong she had dwelt, an evil thing in spider-form, even such as once of old had lived in the Land of the Elves in the West that is now under the Sea, such as Beren fought in the Mountains of Terror in Doriath, and so came to Luthien upon the green sward amid the hemlocks in the moonlight long ago. How Shelob came there, flying from ruin, no tale tells, for out of the Dark Years few tales have come. But still she was there, who was there before Sauron, and before the first stone of Barad-dur; and she served none but herself, drinking the blood of Elves and Men, bloated and grown fat with endless brooding on her feasts, weaving webs of shadow…” (723, Shelob’s Lair, LOTR). The Decapitator still reigns in his underground lair in El Brujo.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spooky spooky spots and why parks are actually scary

What I find most interesting is how darkness is so often the reason for and is used as a description of "scary places" in literature and reality. In chapter 8 Mirkwood is described as "dim...and dark" (134-135) while also being hard to find your way through and relatively restrictive. In the same way, scary places in the real world are often dark an unfamiliar places, my favorite example being the large open pipes you see in parks (what are those called? I have no idea but they are so neat). There is something about being unable to see ones surroundings, feeling suppressed from above, and having only one known entrance or exit that unsettles the human mind. I think this is one of the reasons why we see few underground societies (I am excluding cliff and cave-dwelling peoples because something about being above ground negates the fear I am speaking to here). While Mirkwood is not underground like the pipes, it finds a way to inspire that feeling through its dense foliage and daunting quiet.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skire...Shira Brae....Sharashire?

There is no cool way to merge the Shire and Skara Brae (if you can think of one please DM me immediately)

First and foremost both Hobbit culture and that of the Skara Brae area were formed in relative isolation. The shire is known to operate separately from the rest of the world, and so too is the Skara Brae site described as being "out of the way" compared to the rest of the world. This means that the two cultures likely had little to no outside influence when developing their culture, and thus may have very specific or unique practices compared with the surrounding area.

Next, the two societies had gradual shifts from one generation to the next, often inhabiting the same space as their predecessors. Much like how Bilbo inherits his family home, the Skara Brae inhabitants build over previous homes so that multiple generations are live on the same patch of land. This likely instills a sense of possessiveness over land and space, explaining why the Skara Brae and hobbits would be loathe to take up unnecessary room by making grand structures.

Socially, the two had a focus on family and community life, likely largely due to their isolation. The hobbits gossip and entertain guests as a means to preserve community while the Skara Brae included central hearths to encourage socializing.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hobbits and the concept of "home"

Hobbits seem to be the cozy race of Tolkein's world if they way they treat the home is anything to go off of. From his definition of a hobbit's home, to how Bilbo handles his (mostly unwelcome) guests, Tolkien makes it clear that a pillar of Hobbit culture is curating a sense of welcoming safety. A hobbit's home is described as compact and safe, even if it lacks the grandeur of other places, and despite its small size, Bilbo tries to make his guests feel welcome purely because of how much he values that sense of comfort. This will become more important once Bilbo learns of the home his guests have lost, stirring his sympathy not enough to leave his own beloved home-but to at least enough understand the request. Bilbo makes it clear that his sense of identity comes from not only his community, but his physical home as well. Comfort is something he and his culture value, and to leave his home is more of a sacrifice than those of the other races may understand. Thus, one of the most challenging parts of Bilbo's journey is not the dangers he faces, but the comforts he leaves behind.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robbins and A Funky French Story

If I were to make a story using the same methods as Tolkien, I would turn to old french phrases and double meanings to create interesting characters. For example, my main character would be named Bon Chat, literally meaning good cat but a figurative meaning for a tit or tat, signifying the relationship a protagonist often shares with their narrative. A place of sorrow Bon Chat would take refuge in after failing to execute a minor plot would be a deep lake with many bugs around its edges named Le Cafard (taken from a term meaning " to have the cockroach" but meaning to be sorrowful or blue). Bon Chat would realize a victory would require a sacrifice, turning to his partner Bondos (Bon Dos literally means "to have a good back" but means to be an easy scapegoat) as their only chance. A gaping maw with an evil mind would serve as the spooky villain named Faim Loup (Faim de loup is "to be famished" in a french idiom that literally means to have a wolf's hunger). Bon Chat would banish Faim Loup to the Nuit Blanche (sleepless night literally meaning white night), a land from which there is no return.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantastic post! As a New Mexico native, I greatly enjoyed reading about an outsiders view of our history. The difference between meaning within a place surviving or being erased seems to be a thin and very wobbly line. Perhaps it has to do with the survival of the overall culture in the community, or as we discussed in class last week, the lack of success another belief has of consuming the preceding one.

A Manger in a Sea of Mud response

After this week’s reading about Mother Catherine Seals, I was reminded of the tragic history I learned about when I visited Santa Fe, New Mexico last year. I think this history is largely suppressed, but among the people I was with (my partner, his mother, his friends), the history was very alive.

In short: Santa Fe was first conquered by the Spanish in 1540. The indigenous Pueblo people took it back in 1680, but held it for only 12 years. After this, Spain, led by Don Diego de Vargas, reconquered it. I was disturbed to learn that this was the history behind the yearly Fiesta—quite literally a celebration of de Vargas and the reconquest of Santa Fe. These are huge festivals that happen there every year, and nobody seems to know the history, or at least they don’t care. I can’t believe these festivals are still allowed to happen. The racist and colonialist ideals on which the US was founded is so deeply rooted and ingrained in the culture here, it is so hard to escape. It was really interesting to read about New Orleans this week, where the history built there around Mother Catherine still seems so tangible. In Santa Fe, it all felt so erased and forgotten.

The primary figure behind the colonialist history of Santa Fe is de Vargas–the leader of the reconquest of the city. I don’t think he is anything of a household name, and I’m not knowledgeable enough to know of his lasting impact on the city, which might be clearer to people who live there. I can’t imagine he is remembered fondly, but who knows, when they still have the Fiestas every year. Something that really stood out to me in the text this week was where Gray described how “the organizing principle for the use of space [in the Temple] was simply proximity to Mother Catherine herself” (p. 115). It is really incredible how one person–whether for good or bad–can hold so much influence and power in a particular place. The story of Santa Fe reminds me how detrimental that can be, if in the wrong hands.

Santa Fe Fiesta festivities, 2019. https://www.hellotravel.com/events/santa-fe-fiesta

Weiser-Alexander, K. (n.d.). Santa Fe, New Mexico – The City Different. Legends of america. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/nm-santafe/.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I adore the depth of this post! I especially enjoyed your analysis of Candyman, as I feel it connects to the larger role that a community and its superstitions play in giving value to a place. I have to wonder why there seems to be more urban legends and folklore in underdeveloped areas such as poor communities and rural towns. Perhaps it is the closer sense of community within these areas that allows places to take on a deeper meaning.

the power of religious relics

I think there’s something interestingly eerie about the stories that relics carry. Long after the destruction of the Temple of the Innocent Blood, relics of Mother Catherine “found their way into other spiritual churches and congregations” and continue to carry her reputation of fulfilling all “magical, religious, economic, and secular” needs (p. 118). Also impacted through a focus materiality is the burial site of Saint Peter, also known as St. Peter’s Basilica. I draw similarities between the use of objects as symbols of religious idols. In addition to being the final resting place for Saint Peter, this site is famous for having the skeletal remains of bother St. Peter and Paul and the ‘Holy Umbilical Cord’. Regardless, a church has been present on the land since construction began in 1506.

This location, however, is connected to a much larger religious context, so it differs from the relics and reputation left behind from Mother Catherine’s Temple. The most comparable example that comes to mind is from Candyman (Dir. B. Rose, 1992). The urban legend of Candyman himself is rooted in a poor area of Chicago, which is suffering from segregation in the film. More specifically, he has a history of being manifested in a particular bathroom (pic included). Everyone in the area knows to stay away from this bathroom, for fear of suffering the same fate as the last person that did. Eventually, Candyman obtained a sort of cult-like following, which carries some similarities to various religious practices.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manger in a Sea of Mud

Manger in a Sea of Mud presents the relationship between a culture and the man-made items within it. While natural spaces may also be given meaning, there seems to be something about a space made for man that more easily absorbs meaning and value. As an example, there was an abandoned shack a mile from my school in the country. No one knew its origins or what its current use was. The town allowed the shack to stand despite having little to no meaning to the people around it. However, during my junior year a freshman took his own life within that shack. After his death that building was covered in flowers every day for weeks. Now, there is no discussion about its existence. It holds too much meaning for our town despite holding no inherent value itself. The Temple of the Innocent Blood may have operated in a similar manner as "the material record of the Temple of the Innocent Blood itself is not extraordinarily rich" (p.115) much like my town's shack, but the idea remains the same. Charisma and catastrophe can make a location more meaningful to a culture despite any lack of value or effect on its surroundings.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Basso and Harmansah talk about placemaking

Basso's essay raises an interesting point about how key a native viewpoint is for understanding a new culture. Understanding complex rules, structures and religious practices may take multiple years and multiple people to understand, yet it is also " a task that only members of the indigenous community are adequately equipped to accomplish; and accomplish it they do, day in and day out, with enviably little difficulty" according to Basso (pg3). For me, this raises the question if we as modern academics will ever be able to grasp the true culture of those long dead and far removed cultures of antiquity. While there are many cultures (such as that of China and multiple countries in the Middle East) that retained a connection to ancient roots, many other nations have lost this sense of native-ness that would allow them to so easily understand and contextualize historic pieces from their people's past. Harmansah also references this issue when speaking about how modern cultural practices "both destroys those situated practices but was also nurtured by them" (pg13). Thus, while many people may retain practices similar to ancient ones, the very act of the change and modernization from outside forces erases a portion of the beliefs that helped support it initially. I find that it is hard to find evidence of such change in American culture, largely because American culture is the colonizer that consumed the practices of those it came into contact with.

1 note

·

View note