dee/silas ♤ they/she ♤ medieval history sideblogbanner by sekihamsterdiestwice

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

And on the first anniversary of his coronation, 16 July 1378, Richard [II] attended the wedding of Anne Wake and his second cousin Sir Philip Courtenay, son of the late earl of Devon and a great-grandson of Edward I, and gave them two silver cups and two silver-gilt ewers as a gift, at a cost of over £22.

Kathryn Warner, Richard II: A True King's Fall

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why was empress Mathilda not able to become the ruler?

Hi! There were lots of reasons, and historians have gone back and forth between them over the years. I am not an expert at all, but the way I see it, it was a combination of factors - be it social, structural, or plain bad luck - that resulted in Matilda's inability to claim the throne of England. To list a few I think were relevant:

Misogyny. After his son's death in 1120, Henry I's first instinct doesn't seem to have been to name his daughter his heir but instead to conceive another son with his second wife Adeliza of Louvain. William of Malmesbury wrote that the lords swore to accept Matilda as their sovereign only if Henry I died without a male heir; John of Worcester wrote that Henry designated Matilda as heir as "he had as yet no legitimate heir to the kingdom", implying that Matilda would be the one to provide that heir (ie: a son); and it seems that some of Matilda's supporters like Robert of Gloucester stressed the claims of infant Henry (the future Henry II) from the onset. Some historians have argued that Henry I wished to live long enough to transfer the kingdom and duchy to his eldest grandson, though this is of course mere speculation and Matilda would have been her father's immediate successor for the foreseeable future regardless. So even during Henry I's life, while Matilda was named heir and was expected to inherit & rule England, her exact situation appears to have been complex, and her gender was - directly or indirectly - at the heart of the complication.

Moreover, during the Anarchy, while Stephen technically did not justify or defend his claim to the throne explicitly because of his gender, there was clearly public debate over female succession at that time: for example, Matilda's illegitimate brother Robert of Gloucester was known to reference the Bible, where the Book of Numbers depicted God sanctioning female inheritance when there were no sons. This indicates that Matilda faced opposition from enemy quarters specifically for those reasons. Also, during Matilda's brief assumption of power as a female king, gendered ideals of masculinity/femininity and kingship/queenship entirely dictated public response to her and shaped her negative reputation.

Xenophobia. The Normans and Angevins were historic enemies, and many nobles were incredibly worried about Matilda’s second husband Geoffrey Plantagenet becoming king. I don't think it's a surprise that the Gesta Stephani repeatedly called Matilda "Countess of Anjou" or emphasized the presence of "Angevin knights" among her entourage. This had something to do with gendered expectations as well, but it was also likely meant to highlight Matilda's presumed foreignness, despite the fact that she was a princess of England by birth.

Complicated inheritance patterns. Succession in England, both before and after the Norman Conquest, was incredibly tricky. I'm not even going to get started on the Anglo-Saxons, but going by William the Conqueror's children: his eldest son rebelled against him, his second son inherited while keeping the eldest one imprisoned for life, and was in turn most likely murdered by the third son, who also kept the eldest son imprisoned for life. Hereditary claims were thus overridden in both cases. As Charles Beem points out in the Lioness Roared about Matilda's own father: "Henry I promoted a system of lineal inheritance based on a firm rule of primogeniture [for his children]. However, his own legitimacy as king was not based on this principle, a concept that infiltrated Anglo-Norman inheritance practices during his reign. Instead, he based his self-representation as a legitimate king on a medieval hodge-podge of justifications: porphyrogeniture, or having been “born to the purple” after his father had become king of England, sacralization from his anointing and consecration, and the acclamation of the people: Finally, Henry I secured papal recognition for his title, and convinced Pope Calixtus II to reject the claims of William Clito, the son of Henry’s eldest brother Robert Curthose, in effect dealing a severe blow to the legitimacy of primogeniture." So even in an ideal scenario, the idea of a designated heir and eldest child succeeding without hindrance would have been unusual. Unfortunately, this was not an ideal scenario by any circumstances.

Also, England seems to have functioned with an interregnum at that time, meaning that Matilda would not have been immediately considered ruler upon her father's death. To quote Beem: "To become king of England in the year 1135 required positive, immediate action; although the theory of the king’s two bodies had already begun to develop, the idea that an immediate succession occurred upon the death of a king had not. Instead, an interregnum occurred, which ended only when the crown was placed on the next king’s head. This had been the case with William Rufus’s accession in 1087 and that of Henry I in 1100, both of whom overrode the hereditary claims of William the Conqueror’s eldest son Robert Curthose. Although Matilda had received oaths to support her candidacy, the oaths in themselves did not make her king. Like her uncle and her father before her, Matilda needed to be physically present in London, to receive formal homage from her tenants-in-chief, to accept the acclamation of the people, and to be anointed and crowned in Westminster by the archbishop of Canterbury". I think the first heir to be regarded as king despite not being physically present in the country was Edward I in 1272 - a while away. Which brings me to...

Bad Luck. At the time of her father's death, Matilda wasn't in England or Normandy. She seems to have left her father's court after a disagreement where he refused to be reconciled with William Talvas without punishing him despite Matilda's wishes on the contrary. As Robert of Torigny notes, in the end of 1135, "the empress Matilda, who he [Henry I] had long before appointed heir to his realm, was staying in Anjou with her husband count Geoffrey and her sons"; William of Malmesbury likewise stated that she was staying in France “for certain reasons.” The fact that Matilda wasn't physcally present made it easy for Stephen and the nobles to sideline her and overrule Henry I's appointment.

Matilda was also pregnant at the time, and it's possible that this prevented her for making the crossing, either due to physical reasons (we know she nearly died during her second childbirth) or due to ideological ones (she may have "considered such a state to be a liability in constructing herself as a viable contender for an office essentially gendered male", as Beem speculates).

An insufficient power base: Yet another one of her misfortunes was the fact that Henry I seems to have withheld his daughter's dowry till the end of his life. For example, Torigny writes that "the king was unwilling to do the fealty required by his daughter and her husband for all castles in Normandy and in England". Nor does Henry seem to have associated her with direct kingly governance during his life that could have made the transition to rulership more natural for her and for English & Norman magnates. This meant that Matilda and Geoffrey didn't seem to have had a solid power base to rely on at the time of her father's death with which she could directly launch her claim. It's no surprise that their first move was to try and secure her dowry castles (Exmes, Domfront, Argentan, Ambrières, Gorron, Colmont, etc), and that Matilda installed herself in one of them.

And, of course, Matilda's ultimate bad luck was the existence of a rival claimant (Stephen) with sufficient resources and backing who chose to press his own - theoretically inferior - claim. Ultimately, after the majority of nobles sided with or acquiesced to Stephen, Matilda's doors were shut - without tangible support, she was stuck. It's not surprising that it was only after Stephen began to alienate his followers (particularly Robert of Gloucester, who had initially supported him) a few years later that Matilda got an opportunity to press home her advantage.

Hope this helps!

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes I just think of this:

A very curious entry in Edward’s account, while he and Hugh were at Eling just outside Southampton on their way to Beaulieu, talks of the village as the place ‘where the king frightened Sir Hugh.’ Presumably this means a practical joke or prank of some kind as the word can also be translated as ‘startled’, and Edward was a very playful type of person although Hugh himself was not.

and want fic of Edward II and Hugh Despenser the Younger just hanging out together.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

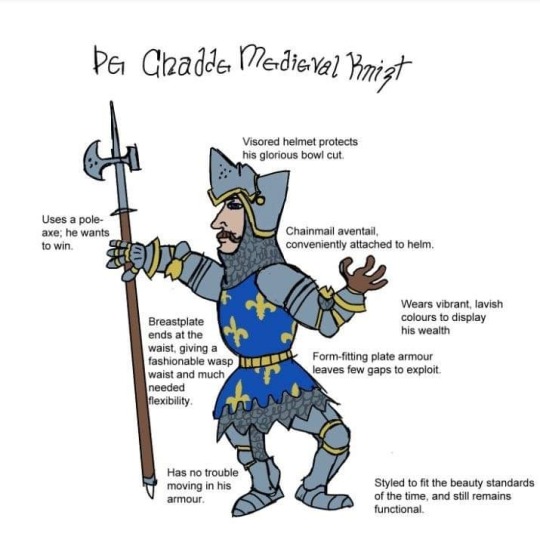

A helpful assortment of Armor and Sword charts for writers and historians alike.

4K notes

·

View notes

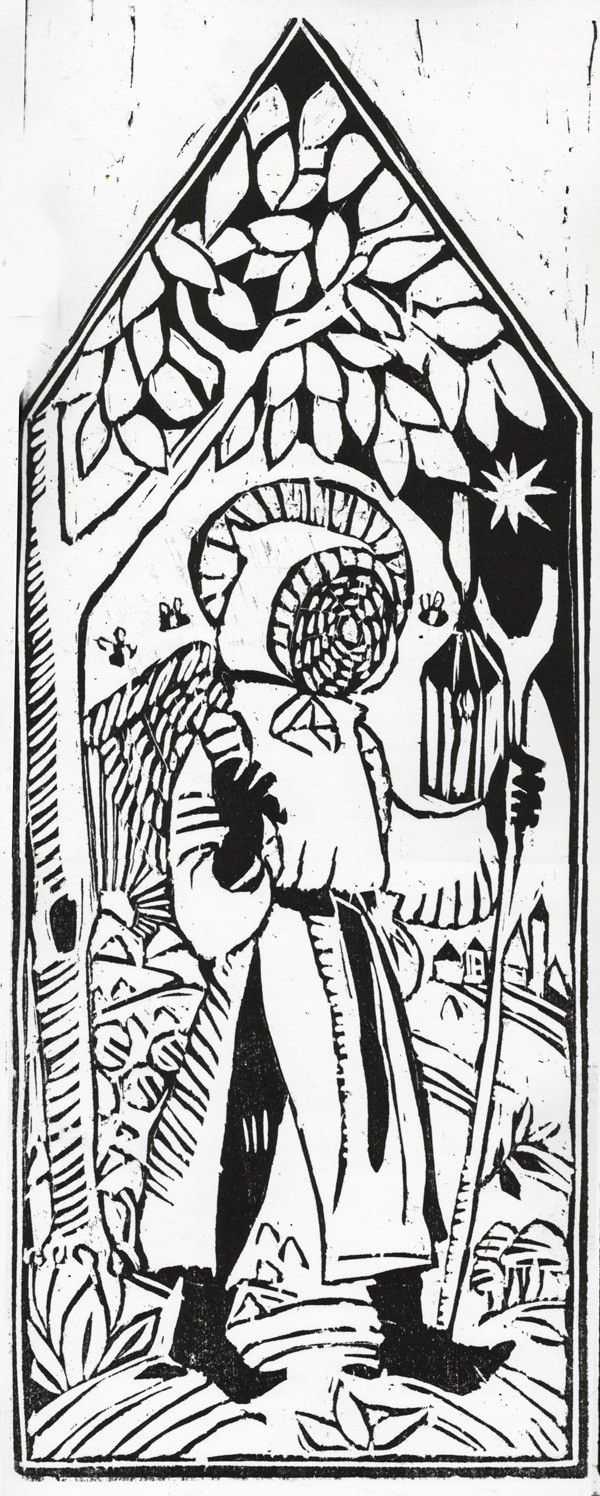

Photo

the cathedral

“Hours of Étienne Chevalier”, Tours c. 1452-1460

NY, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.2490

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

I was at the scriptorium, drawing myself as an animal of my choosing - a donkey, of course. Then brother Eustace approached me and laughed, since it was me depicted as an animal. I hath told him that if he truly wishes to enter the kingdom of our Lord, then he must laugh not at me, but at himself. He then promptly ran from the scriptorium, and brother Herbert told me that he saw him crying. Did I hurt him? Oh, Lord forgive me, I shall do my best to apologise... I did not mean ill on him, I simply wished to remark on his demeanor. Oh, I must find him...

191 notes

·

View notes

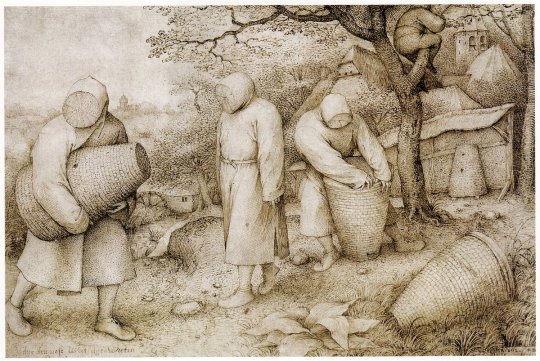

Photo

v1 of my handmade medieval beekeeper costume from around may :) + references

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

Carved bone crozier featuring the Lamb of God, Northern Italy, circa 1360-1400

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a pic of coronation of Richard iii and Anne nevile. But why Richard is looking at his wife like this ? As if he was very happy to see his wife being coronated as queen of England, rather than himself coronated as King of England . 🤔🤔

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mermaid on Fresco ~ late 14th century ~ St Olaf's Church ~ Poughill ~ Cornwall, England

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

German school, An Open book, early 16th century

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

horse armour/barding

from an illustrated manuscript catalog of the armories of maximilian I, innsbruck or vienna, c. 1540

source: Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 10815, fol. 55r

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

Initial letter, priest blessing a new house. Pontifical : manuscript, [ca. 1380-ca. 1425]

MS Typ 1

Houghton Library, Harvard University

191 notes

·

View notes