Photo

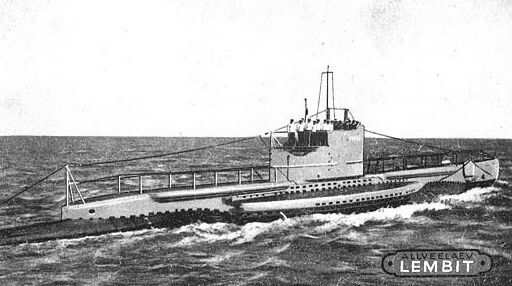

Lembit: a submarine like a pre-WW 2 time capsule

This post is a little different in various ways: it is about a military ship (stretching the definition of “infrastructure”), it touches on political history and most importantly, it is the first time I could visit the subject of a post myself and take some photos of my own. This was made possible due to an internship at the Estonian Maritime Museum (Eesti Meremuuseum) which allowed me to see one of the highlights of the museum for free, the submarine Lembit, wonderfully preserved and mostly restored to its original pre-WW 2 interior.

Until it was carefully lifted out of water in 2011 and turned into a museum ship in the Lennusadam (Seaplane Harbor) part of the Estonian Maritime Museum, it was the oldest submarine still afloat, having been custom-built in 1935-1936 in England and in 1937 taking part in the coronation naval parade of King George VI before being transferred in the same year to the Republic of Estonia to patrol its long coasts and train sailors. It is the only boat of its pre-WW 2 navy that remains intact, having survived WW 2 (unlike its sister ship Kalev, after which the this class of submarines are called Kalev class submarines) and the years of German and Soviet occupation during and the Soviet occupation after it. After the regaining of independence of Estonia in the early 90s and before becoming an exhibition object, during 1992-1994 it oversaw the departure of former Soviet troops that the occupiers had stationed in the country. (For more historical context, see the Wikipedia article on the history of Estonia)

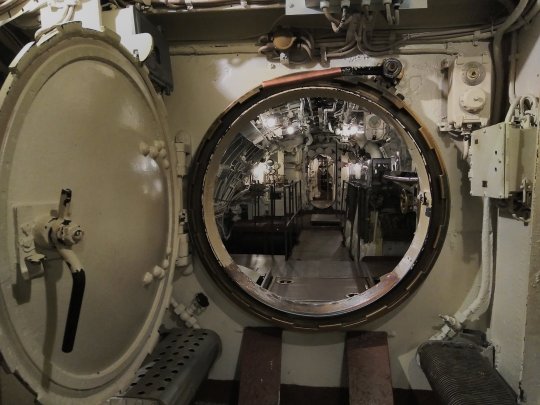

Visiting the submarine is a bit like traveling back in time, aside from some modern lighting, a few loudspeakers and some protective glass the submarine is still largely how it was during its early years of service in the late 1930s, with most of the Soviet alterations (such as a training pool installed in it at one point) removed during restoration works in the 21st century. The new resting spot in the museum not only makes it possible to view the submarine from unusual angles that would usually require diving, but also protects the vessel against further corrosion.

Built by the Vickers-Armstrong Ltd. company in Britain by British workers and Estonian naval personnel under the (according to contemporary British statements) enthusiastic oversight of Estonian experts, the submarine has a number of special features. It was able to move through thin ice, which was needed due to large parts of the Baltic Sea regularly freezing over during the winter.

Furthermore, it could lay special mines designed in Estonia, possesses an anti-aircraft gun manufactured in Sweden as well as a machine gun, and, unusually, could fire two types of torpedoes, which were measuring 5.86/7 m (19.2/23 ft) in length and weighing 910/1565 kg. Eight could be on board in total, stored in the room at the bow (the front) of the ship, where also a majority of the personnel slept (16 out of 29-30, not counting officers).

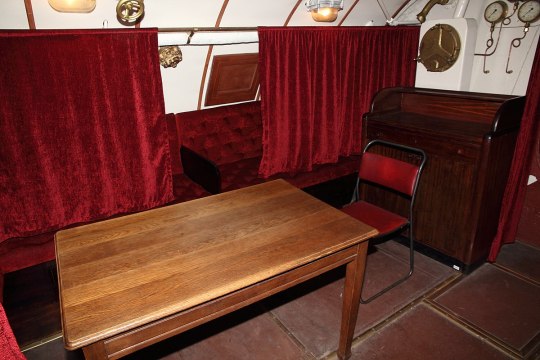

The ship itself is 59.5 m (195 ft 3 inch) long and could displace 665 tons of water when surfaced and 853 tons when submerged. Next to the torpedo room is the saloon of the officers with more comfortable beds with curtains, the captain’s cabin (the only one to have a dedicated cabin) as well as a table with chairs and a bathroom restricted to the four officers onboard.

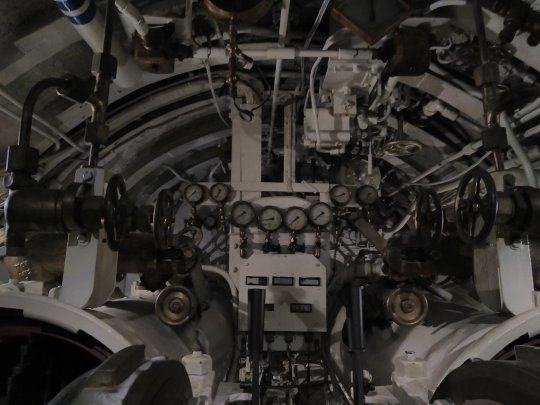

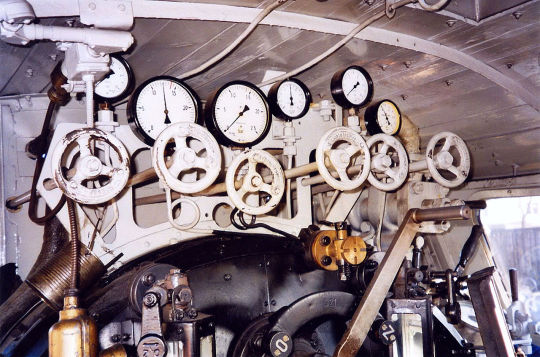

Neighboring the living room of the officer is the control room. It contains the steering wheel, a periscope, a desk with a map of the waters, the radio room, the galley (the kitchen) of the ship as well as numerous other devices and objects. Notable is that the water sink has two water taps, a sign that the ship was built in Britain.

The two photos on the top show the control room seen coming from the bow, whereas the third photo shows the view coming from the opposite side, where the engine room is located. The submarine has two diesel and two electric engines onboard and could stay underwater for about a day at a maximum depth of 90 m (295 ft).

While surfaced, it could endure up to 28 days away from coasts or support ships and its range was 2,800 nautical miles (5185.6 km/3222.2 miles) surfaced and 90 nautical miles (166.7 km/103.6 miles) submerged. These lengths were however significantly reduced if going at maximum speed (8.5 knots / 15.7 km/h submerged and 13.7 knots / 25.4 km/h surfaced).

Topmost picture: The engine room, coming from the stern (the back) of the submarine. Second photo from top shows a similar view, here one of the electric engines is also clearly visible in the lower left corner. Second photo from the bottom: Controls of the electric engines. Bottommost photo: The diesel engines.

The last room had additional beds for sailors, additional devices and machinery as well as the toilet of the sailors and chests with their personal belongings.

Further reading:

Introduction on the homepage of the museum

Arto Oll: Allveelaevad Kalev ja Lembit / Submarines Kalev and Lembit (2019)

Arto Oll: Kalev ja Lembit. Eesti allveelaevade lugu (2017)

Uboat.net: Allied Warships of WW II, Lembit

Image sources:

Black/white photos: Unknown author, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Color photos: Photos released into the public domain by Wikimedia Commons user MKFI (interior photo of the museum, torpedo room overview, saloon, diesel engines and controls of the electric engines) and photos taken by the author.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey I just want to say that this blog is really cool and it's a bit sad that it's on hiatus. also I already knew some of the places mentioned because Tom Scott made a video about them. and the header image is from my hometown <3

Hello! I have to thank you for the support, it means a lot, especially since you are the first to message me here with it. :) It's so nice to hear about people liking this blog that I have spent so many hours on.

Sorry for the inactivity, I have been working on other projects in the meantime (such as @ystel) and other writing projects, but I am happy to announce that I had an opportunity to visit a place with interesting infrastructure myself now so I have been preparing for new posts, this time with my own photos! I hope you will enjoy them. Aside from that, I have a list of topics I am still planning to cover at some point.

Also, you are from Rostock? Cool, a friend I have is from there and I took the photo once when I was visiting him. I studied in Greifswald so Rostock was never too far.

Have a nice a day and night and once again thanks for writing!

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

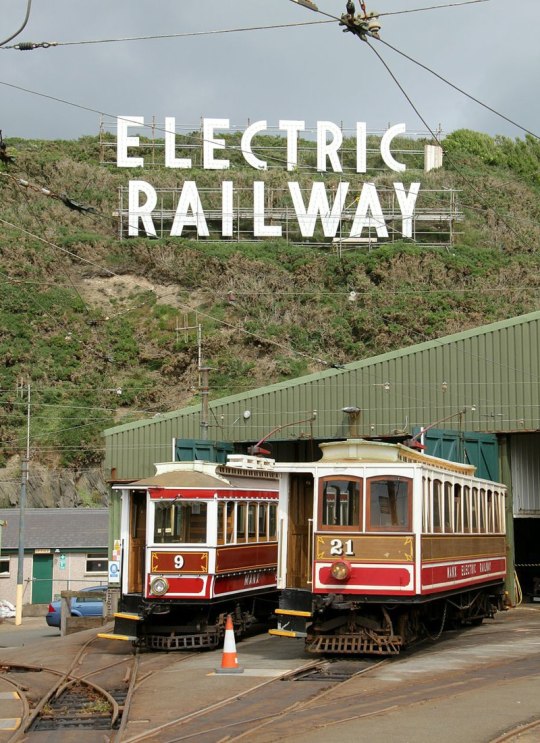

Manx Electric Railway

The Manx Electric Railway, operating on the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea, is one of the few still operating interurbans, or the original type of electric trams or streetcars operating between towns in the world that were widespread in some countries in the early 20th century.

It began operating in 1893 to support the growing tourism industry and help transport tourists to other locations alongside the coast further away from the capital of the island, Douglas, totaling 16 stops. In addition, it also transported goods and animals. While this has now ceased, it has remained in use as a tourist railway. Most of the trams and other infrastructure from the early, Victorian and Edwardian, times are still functional, including a streetcar from the opening year (Car No. 1, fourth, fifth and sixth image from above) that has been said to be “oldest working electric car in the world”.

The line was so quickly extended that in 1900 caused the company running the interurban line to get into deep financial problems and be subject to foreclosure, which caused the collapse of the lending bank, the local Dumbells bank. Local bankruptcies, life saving losses and trials with sentences followed. As a result, the line was put under new management.

In 1957 the Electric Railway was nationalized after new financial problems. Following this, the government began to invest heavily in the line. Nonetheless, in 1975 mail transport was suspended, as was temporarily the section from Laxey to Ramsey until public protest led to the decision being reversed. The section was then shut down again in 2008 for track repairs supported with funds from Tynwald, the parliament of the island, before being reopened in the same year.

More information:

Official website with history section until 1993

Isle of Man Guide: Manx Electric Railway

Mike Goodwyn: Is This Any Way To Run A Railway? The Story of the Manx Electric Railway Since 1956 (1976)

Mike Goodwyn: Manx Electric (1993)

Manx Electric Railway Society: Manx Electric Railway Laxey-Ramsey line 2008 closure

Frank M. Rowsome, Stephen D. Maguire: Trolley Car Treasury (1956)

George W. Hilton, John Fitzgerald Due: The Electric Interurban Railways in America (1960)

Image sources:

Topmost image, at Derby Castle: Alan Murray-Rust, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from above: el ui, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from above, Laxey Valley from South Cape in 1974: Dr Neil Clifton, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fourth image from above: Dr Neil Clifton, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fifth image from above: Andrewrabbott, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sixth image from above: Chris Coleman, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from below: Spsmiler, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Map: OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Steam carriages, part 3: French steam cars

Continued from part 2.

In England steam car development got to a halt with the Turnpike Acts in 1840 levying disproportionately high tolls on steam cars in comparison to horse-drawn carriages. It was then even more discouraged with the Locomotive Act of 1861 that limited the speed of steam cars to 4 mph (6.4 km/h) outside of cities and 2 mph (3.2 km/h) inside cities, slower than walking speed, as a man with a red flag was now required to walk in front of the vehicle.

In France however such restrictions did not exist, and so in 1873 Amedée Bollée, a bell founder, built the country’s first steam car put into practical use, capable of transporting 12 people, a conductor and a driver called the L’Obéissante. The name “The Obedient” stems from the good and smooth steerability.

It had a tubular boiler delivering steam to two engines with two cylinders each arranged in a V-shape, and used a chain drive to connect those to the wheels. The total weight of the vehicle was 4,800 kg.

Its normal speed was 30 km/h (18.6 mph), with a top speed of 40 km/h (24.9 mph) possible, and could climb gradients of 12 %. The inventor managed to travel the 230 km (142.9 miles) from Le Mans to Paris in 18 hours (including breaks) and was greeted with a triumphal welcome. As a result, it has sometimes been deemed to be the ancestor to the modern car. Bollée later went on to construct several more models of steam-propelled vehicles. Another important inventor and manufacturer of steam cars in France was Léon Serpollet, whose cars with four cylinders, a much more compact engine, and four seats facing the road, already much more resembled later private cars.

While a small car industry was now developing in France and also Germany, it took until 1896 for the conditions for steam cars in England to improve, when the Locomotives on Highways Act was passed, allowing for speeds of up to 14 mph, later reduced to 12 mph. The requirement for a pedestrian with a red flag to walk in front of the steam car had already been eliminated earlier. The change came after the success of cars with internal combustion had seen success on the European mainland and swayed public opinion in Britain.

Read more:

Peter Gould: The Steam Bus 1833-1923 (pewtergould.co.uk)

Cédric Mastellari. David Wharry (translator): L'Obéissante steam-powered omnibus (Google Arts & Culture)

William Baxter Jr.: The Evolution and Present Status of the Automobile (Popular Science Monthly, Volume 57 from August 1900)

antiqbrocdelatour.com: Amedee Bollee L'Obeissante, voiture vapeur 1873 (in French)

Lyman Horace Weeks: Automobile Biographies (1904), via Project Gutenberg

Image sources:

Topmost image, from 1875: Unknown photographer, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top, from 1923: Agence Rol, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from top, museum exhibit: Buch-t, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottommost image, a car made by Serpollet: Unknown author, from Popular Science Monthly Volume 57 from August 1900, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Matekane Air Strip: The runway capable of pushing any pilot over the edge

Matekane Air Strip (ICAO code FXME) in Lesotho is notable not just for the high altitude at which it is located (2299 m or 7544 feet) but especially also for having its runway end right at the edge of a cliff. Planes that fail to take off after just 579 m (1900 feet), or previously 400 m (1,312 feet) of paved runway fall into a roughly 610 m (2,000 feet) deep abyss. And according to bush pilot Tom Claytor this is not uncommon with adverse winds, but in fact to be expected and pilots are required to use the fall to glide and gain enough speed to get sufficient lift to avoid a crash.

The airstrip has no facilities or equipment aside from two windsocks and was closed in 2009 for international travel, and while it was still used by doctors and NGOs after that as well as domestic air travel and private airplanes as late as 2020, several aviation websites now list it as entirely defunct.

Read more:

Video of take-off and landing

Impressions of the surrounding landscape

Short 15-minute documentary about the airport and the surrounding environment (2020)

Farhad Heydari: The World’s Scariest Runways (travelandleisure.com March 10, 2015)

Orangesmile.com: Matekane Airport, Lesotho

Great Circle Mapper: FXME, Matekane [Matekane Air Strip]

Bigorre.org: Aviation weather, VAC and NOTAM for Matekane Air Strip airport (FXME)

Image source:

Tom Claytor - www.claytor.com, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PS Waverley: The last seagoing paddle steamer in the world

Launched in 1947 in Scotland, this ship was initially being used for various ferry and charter trips, mostly from Craigendoran, a suburb of Helensburgh in the west of Scotland located on the mouth of the Clyde River 40 km (25 miles) northwest of Glasgow, to the village of Arrochar on Loch Long. From 1948, after the nationalization of railways and their steamers it belonged to the British Transport Commission and Caledonian Steam Packet Co., and from 1952 to 1972 to the coast fleet of British Railways Caledonian Steam Packet Co Clyde.

In 1974, the ship, now already the last seagoing paddle steamboat in the world, was after a long time of declining passenger numbers sold for £ 1 to the Paddle Steamer Preservation Society. It has since undergone several substantial repairs as well as yearly maintenance and is still used from May to October every year for various excursions around Britain, mostly near Glasgow, but also including trips on the Thames to London and other regions.

The ship is 73.13 m (239 feet, 11 inch) long, 9.19 m (30 feet, 2 inch) wide and is depending on the water it is currently allowed to carry 740, 800 or 860 passengers. Until 2013, the highest limit was 925, in 1947 it was 1350. 19 crew members are required, or 15 in protected waters.

It has a triple-expansion or three-stage steam engine with 2,100 horsepower and can achieve speeds of 18.37 knots (21.14 mph or 34.02 km/h), while normal speed is 14 knots (16.11 mph or 25.93 km/h). Until 1957 coal was used for fuel, then until 2019 fuel oil, and currently marine gas oil. The boiler has been replaced three times, most recently in 2020.

Read more:

History page on the official website of the ship

Paddle Steamer Preservation Society: Paddle Steamer Waverley

Gordon Stewart: Paddle Steamer Waverley (paddlesteamers.info) with many additional photos

Image sources:

Topmost image, at Portsmouth Harbor: Barry Skeates, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: Robert Mason, CC0 (Public Domain license), via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from top, in London: Chris Gunns, CC BY SA 2.0, via WIkimedia Commons

Fourth image from top, on the mouth (Firth) of the Clyde River: Phil Sangwell from United Kingdom, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fifth image from top, in the Scottish town of Oban: Adam Sommerville, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from bottom, in the Scottish town of Largs: Ronnie Macdonald from Chelmsford and Largs, United Kingdom, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from bottom at the Landing Bay of the island of Lundy in the Bristol Channel: Roger Davies, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottommost image: Pam Fray, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

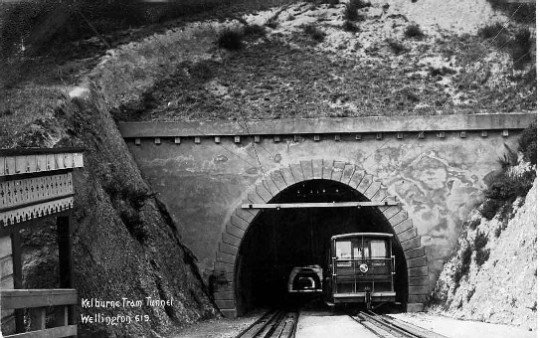

Wellington Cable Car : The Cable Car that became a funacular

Following the boom of the 1890s, when Wellington was the fastest growing town in New Zealand, a cable car line was constructed and opened in 1902 to connect the center with some of the hilly terrain next to it, at the time some of the last remaining land that provided space for new housing in proximity to the center. Additionally, the line also provided easy access to the Botanic Gardens, to a scenic view of the town including the coast, and to a transit link to the suburb of Kelburn. It is frequently used by commuters and students at the Victoria University.

The nearly 400 feet (122 m) long journey takes about five minutes to climb the hill with a gradient of 17 %, passing three tunnels (two with artistic light installations) and crossing three bridges on the way.

Upon opening, the cable car was met with much enthusiasm and became an increasingly popular mode of transport as well as a local attraction. 4,000 people were carried on the first weekend alone, and 425,000 in the first year. A decade later the number of yearly passengers had grown to a million, and in 1926 the number had reached two million, more than there were people in New Zealand at the time. The popularity and reliability earned the cable cars the name “Relentless Red Rattler”.

The cable car was first propelled by a steam-driven engine in a winding house, and switched to electricity in 1933. In 1978, following large renovations of the cable car and major technological change that made the line become a full funicular, the winding house was closed before being reopened in 2000 as a museum. The line remains popular with residents and tourists and still carries about a million passengers in a normal year.

Read more:

Museums Wellington: Cable Car History and Cable Car Museum

Wellington City Council: Wellington Cable Car Limited

Pamela Wade: World Famous. Wellington's Cable Car (stuff.co.nz, November 23, 2019)

Gavin, Spersephone: Wellington Cable Car (Atlas Obscura)

EngineeringNZ.org: Wellington Cable Car System

Image sources:

Topmost image: Brett Taylor from Wellington, New Zealand, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: Nelson Pérez, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from top: © Jorge Royan, http://www.royan.com.ar, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fourth image from top: Andrewrabbott, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fifth image from top: Michael Coghlan from Adelaide, Australia, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

First b/w photo from top, taken in 1903: Albert Percy Godber, from the Godber Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Second b/w photo from top, taken in 1910: Unknown author, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Third b/w photo from top, taken in 1970: U.S. Navy photo, from the USS Shangri-La (CVA-38) 1970 cruise book, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottommost image: Karora, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

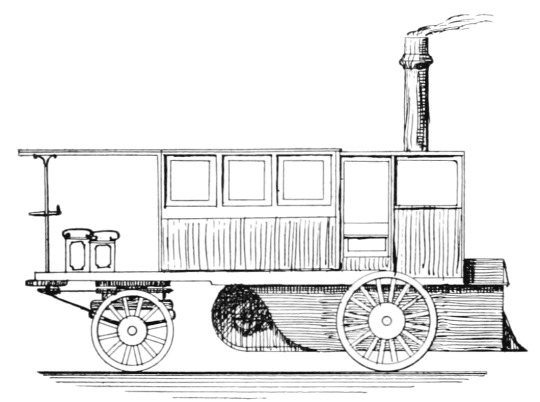

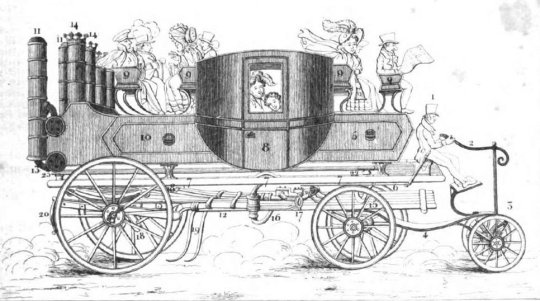

Steam carriages, part 2: The Enterprise, the first steam vehicle designed to be an omnibus

Continued from part 1.

Created by Walter Hancock, who already invented several steam engines and a steam vehicle termed “Infant”, it ran from the 22nd April 1833 a regular line from London Wall via Islington to Paddington. It was the first self-propelling vehicle specifically designed for such a purpose, and so arguably the oldest ancestor of modern buses, but already contained several inventions still in use today, such as the steering wheel.

It needed between 45 and 60 minutes for the journey of about ten miles and could transport 14 passengers, who were sitting on the water tanks used for the engine.The vehicle had three workers on board, a driver responsible for steering and speed, a worker responsible for the engine and the boiler, and finally a worker taking care of the fire and the brake.

A later vehicle, called the “Automaton” and built in 1836, had 22 seats, 24 horsepower and could already reach speeds of more than 20 mph (32 km/h). It was used on over 700 journeys between London and Paddington or Islington and between Moorgate and Stratford, carrying more than 12,000 passengers.

Similar to other inventors of steam cars, he gave up in 1840 due to the Turnpike Acts imposing excessive tolls, strong opposition by horse carriage drivers and poor street conditions.

Continued in part 3.

Read more:

Peter Gould: The Steam Bus 1833-1923 (pewtergould.co.uk)

Tom Brogden: 1802 Walter Hancock's 'Enterprise'. Built by Tom Brogden (steamcar.net, 17 July 2008)

Donald & Carolyn Hoke: Walter Hancock Stratford, England. The Enterprise Steam Omnibus (virtualsteamcarmuseum.org) – has many additional illustrations, including in color

Digital Mechanism and Gear Library: Hancock, Walter (1799 - 1852) (dmg-lib.org)

Walter Hancock: Narrative of twelve years' experiments, (1824-1836) demonstrative of the practicability and advantage of employing steam-carriages on common roads. (1836)

Image sources:

Top: Popular Science Monthly Volume 57 (Year 1900), Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottom: Engraving from 1833 made by C. Hunt, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

0 notes

Photo

Courchevel Altiport: A tiny airfield nested into the Alps

Opened immediately adjacent to the large ski resort of Courchevel in the Trois Vallées region of France, this altiport (a word referring to an airport located at a high location specifically coined for this airfield) is located 2007 m (6585 ft) above sea level, a record in Europe. It has a tiny 537 m (1761 ft or 0.333 miles) tarmac runway with the highest gradient of any tarmac runway worldwide, at 18.6 %. At the end of it, the ground opens up to reveal a slope. The drop can be up to 300 m (984 ft).

Born out of the idea to improve the connectivity of ski resorts, preparations for the first flights began in 1961 and the first plane landed on January 31, 1962. Initially, passengers had to ski to their planes. A hangar exists as well as a caterpillar to groom the runway, but an instrument landing system is not available.

Due to the difficult terrain that allows no aborted take-offs and the short runway length a special qualification is required from a pilot wanting to land on Courchevel Altiport, as with the mountains and slopes around the airfield any mistake could prove to be fatal.

Commercial air traffic is limited both by law and by the fact only few airplanes are able use the airfield, such as Twin Otters or the Swiss-made Pilatus PC-12. Another model from the same manufacturer, the PC-6, was used during the shooting of the James Bond movie Goldeneye that took place in Courchevel. The 007 movie Tomorrow Never Dies was also shot in Courchevel.

The airfield today is mostly used by helicopters and private planes. it is also a popular starting location for scenic flights to Mont Blanc, Europe’s tallest mountain outside the Caucasus Mountains.

More information:

Video of a landing and a take-off

Privatefly.com: Courchevel Airport by private charter

Alpine-airlines.com: Courchevel Altiport Altiport access authorization. History of the Courchevel altiport (at the bottom of the page)

Pilatus-aircraft.com: Courchevel Altiport – Mit dem PC-12 durch Europa direkt ins Skigebiet (June 8 2021)

Andy Herzog: Altiport-Courchevel - der "Flugzeugträger" in den Alpen (Austrianwings.info, April 1 2013)

Image sources:

Topmost image: qwesy qwesy, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: Piponwa, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from top: Peter Robinett, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Airboats: Using aircraft engines to speed across water, ice and marshes

Unlike the attempts to retrofit aircraft engines with propellers onto railway cars, such as the Aerowagon or the Dringos car, which never managed to catch on due to a variety of issues, boats with aircraft propeller engines had more success. They are called airboats, but are also known as fan boats or swamp boats, and can reach speeds of up to 135 mph (217 km/h).

Models with aircraft engines on top of a normally flat bottom made of wood, aluminium or fiberglass are still commonly used today for transport on shallow waters, marshlands, swamps and even ice, anywhere where a submerged propeller as is otherwise common on motorboats would be a problem. In these areas they are important for subsistence hunting and fishing, rescue operations, tourism, and to help with conservation in e.g. bird refuges.

The first recorded airboat-like vehicle, named “Ugly Duckling” was a catamaran built and tested by Alexander Graham Bell and Cyrus Bell in 1905 in Nova Scotia, reaching however only speeds of 4 mph (6.4 km/h). Further airboats were invented in Brazil and France in 1907, were they were known as hydrofoil and hydroglisseur. In the 1920s and 1930s Airboats started becoming more common in regions like Florida and Louisiana.

However, the first predecessor of most of the airboats built and in use today was built near the Bear River refuge in Utah in 1943 by Leo Young, G. Hortin Jensen and Cecil Williams. It was later called Alligator I and constructed to help biologists travel across mud, wetlands and shallow water of the world’s largest migratory wildfowl refuge faster, which previously had to be waded through or slowly traversed on boats with flat-bottoms. Jensen and Williams later started an airboat business that supplied customers around the world.

Read more:

Fred Poyner IV: Airboats. Remote Access Watercraft (The Filson Journal, April 29, 2021)

Ray Grass: World's first airboat hatched at Bear River refuge in '40s (Deseret News, March 8 2007)

Valerie Mellema: Air Boats and Fan Boats Guide (Boattrader.com)

Robert Dummet: Rescue on the Chattahoochee (FireEngineering.com, 1 January 2006)

Alexander Graham Bell, Cyrus Adler: Aërial Locomotion. With a Few Notes of Progress in the Construction of an Aërodrome (1907)

Image sources:

Topmost image: G. Hortin Jensen of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: United States Geological Survey South Florida, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottommost image: Dr. Alexander Graham Bell and Cyrus Adler, Public Domain, National Geographic January 1907 via Wikimedia Commons

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Molli railway: The train using streets of the city center

The Molli Railway (known as “Bäderbahn Molli” in German or Spa Railway Molli) in the northwestern part of the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern is a regularly scheduled railway service still using steam engines. Unique about it is in particular how in the town of Bad Doberan tracks are laid on top of regular streets in the city center, similar to trams or cable cars. Outside of the town it passes woodland and cornfields, and Europe’s oldest racing track for horses.

Built in 1886 after a concession was given by the horse-racing fan Grand Duke Frederic Francis III. as a private narrow-gauge railway that was nationalized in 1890, it today runs 15.4 km (9.57 miles) from the spa town of Bad Doberan to the seaside spa town of Heiligendamm and since 1910 to the spa town of Kühlungsborn with nine stops in total (see map). From 1910 to 1969 it also carried freight and mail. Today it is privatized again, but 98.5 % of the company are still owned by the county and the towns of Bad Doberan and Kühlungsborn.

Of the 32 railway cars built between 1910 and 1930 28 are still in use with original wooden furniture, although a more luxurious salon car is added to some trains (second and third image from the bottom). Three steam engines from Orenstein & Koppel (99 321 – 323) are also still in service even today. Another steam engine was built in 2009 as a fully functional replica of the same series in the town of Meiningen (Thuringia), the first steam engine built in Germany to be used in regular railway service in more than 50 years.

According to an often told anecdote, the train was named “Molli” after the pug of one of the first passengers soon after opening, an elderly woman. The dog, refusing to enter the train, ran away, leading the woman to call out “Molly, stop!” Mistakenly the train driver thought the lady was referring to the train, and stopped the train that had just set itself in motion.

More information:

Andrew Eames, Barbara Geier: Germany Holidays: the Molli

History page of the official website and company introduction (in German)

Berlin.de: Molli Bäderbahn: Eisenbahn Nostalgie an der Ostsee (in German)

Ostsee.de: Mecklenburgische Bäderbahn Molli (in German)

Video of the train by The Tim Traveller on Youtube

Image sources:

Topmost image: Simon Tunstall, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: Rainer Halama, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from top: Softeis on the German Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fourth image from top: Sir James, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fifth (left) and sixth (right) image: Christian Thiele (APPER), CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from the bottom, salon car: W. Bulach, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from the bottom, salon car interior: An-d, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Map: Muns based on OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

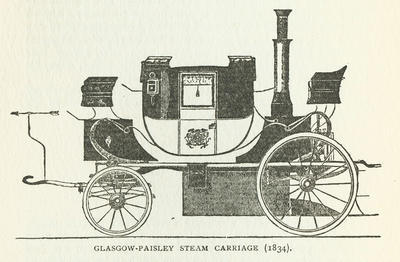

Britain’s first modern bus lines: Steam carriages in England and Scotland

Before the invention of diesel buses with combustion engines, cars and buses used steam. The first of those was constructed by Sir Goldsworthey Gurney. On the nine-mile (14.5 km) route between Gloucester and Cheltenham Sir Charles Dance operated one of his steam tractors (see first two images), reducing the time needed for the trip to 45 minutes.

In Scotland, the first steam carriage was designed by John Scott Russel (born in Parkhead) in 1831 (see bottom image). In 1834 six were built by his company Steam Carriage Co of Scotland. They could reach a speed of up to 20 mph (32 km/h) and carry forty passengers. It was meant to run on a Glasgow-Edinburgh route, but local road officials objected and the route was changed to Glasgow-Paisley instead.

While not being fast by today’s standards, this nonetheless was seen as “high speed” by local road officials collecting tolls and claimed to be damaging to the roads, although evidence by a House of Commons Select Committee found the opposite to have been true, with the hooves of horses and narrower wheels of the horse-drawn carriages causing more damage to the streets than steam carriages.

Nonetheless, huge additional tolls were imposed on steam carriages in 1840, with the road toll between Liverpool and Prescott being raised to 48 shillings to them while remaining at 4 shillings for horse carriages.

Accidents were another problem. Stones or sabotage such as laying a steel rod on the road caused accidents on both lines that led to the steam buses being either damaged or even having their boiler explode, killing several passengers and bringing the services further into disrepute.

The cheaper cost of running steam carriages, among other advantages, was posing a threat to the business of existing carriages who proved to be powerful opposition.

Continued in part 2.

Read more:

Peter Gould: The Steam Bus 1833-1923 (pewtergould.co.uk)

Glasgow City Council, Libraries Information and Learning: Steam Carriage, 1834, Mitchell Library, Glasgow Collection (theglasgowstory.com)

Bruce L. Benson: The rise and fall of non government roads in the United Kingdom in Street smart. Competition, entrepreneurship and the future of roads (p. 263-264)

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica: Sir Goldsworthy Gurney (britannica.com, 1998)

Donald & Carolyn Hoke: Goldsworthy Gurney's Steam Carriage (virtualsteamcarmuseum.org) – has many additional illustrations, including in color

Image sources:

Topmost image: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Vol. 10, No. 287, December 15, 1827, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: German magazine Das Ausland, 1828, No. 11 and 12, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottom image: Popular Science Monthly Volume 57 (Year 1900), Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Madeira‘s airport: A Runway extended into the sea with the help of concrete pillars

The airport of Madeira, officially called Cristiano Ronaldo International Airport (after the famous football/soccer player who was born on the island), like many other island airports, faced difficulties during construction and throughout its history, and poses challenges to pilots approaching it.

Madeira is a Portuguese island in the Atlantic ocean with very hilly and mountainous terrain, which meant there was not much space for an airport. As a result, when the airport first opened in 1964, its runway only had 1600 m (5,249 ft), and being also so close to the sea saw some serious accidents happen. In the 1980s the runway was therefore lengthened by 200 m (656 feet, see second image from top, from 1990).

After that, there was no more suitable land available to extend the runway further, but Madeira’s continually growing popularity among tourists still made a longer runway needed. Engineers came up with the unusual idea of installing 180 concrete pillars of 120 m (394 ft) height into the lower ground, 60 m of which is underground where the ground was not solid enough. To facilitate construction work, the bay below the pillars was reclaimed from the sea. On top of those pillars additional approximately 1000 m could be installed, work which was finished in 2000. Today, the runway measures 2,777 m (9,111 ft). The runway extension won the Outstanding Structure Award of the International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering in 2004.

Nonetheless, the airport remains challenging for pilots, as an instrument landing system (ILS) is due to the difficult, mountainous terrain not available, and a visual approach that includes a 150-degree turn right before landing is required. Strong crosswinds from various directions can pose an additional problem. Therefore, pilots wanting to land on the airport require special schooling, which is likely one reason why there has only been one accident since 1977, the causes of which are not clear.

Aside from technological marvels, some natural beauty can be found as well, such as a number of flowers including the ‘Pride of Madeira’ (Echium candicans, bottommost image).

Read more:

SKYbrary: Cristiano Ronaldo International Airport

Astrid Röben: Airport Madeira International – Hier fliegt der Chef (AEROinternational.de, 30 January 2018, in German)

Guillaume Borde: The 2 Reasons why Madeira Airport is so Dangerous (Rootstravler.com, August 5, 2020)

Cynthia Drescher: Portugal Officially Has a Cristiano Ronaldo Airport, Complete With Questionable Statue (Condé Nast Traveler, March 29, 2017)

Kaushik Patowary: Strange Airport #3: Madeira International, Portugal (Amusing Planet, November 19, 2011)

IABSE.org: Funchal Airport Extension, Madeira Island, Portugal (Archived version)

Airport-technology.com: Madeira International Airport Modernisation, Madeira Island

Wonderfulinfo.com: Madeira Airport, an Airport on Pillars

Madeira-web.com: Cristiano Ronaldo Madeira International Airport (FNC)

Madeira.best: Madeira Island Airport

Image sources:

Topmost image: Bingar1234, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: Peter Forster, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from top: Andrei Dimofte from Stuttgart, Germany, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fourth and fifth images from top: Karelj, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons (left), and Manfred Kohrs, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons (right)

Second image from bottom: Voyager747, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottommost image: sarang, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Water slopes: Giving boats a little push

Water slopes, also known as water slope tractors or in French pente d’eau, are a rare special form of inclined planes, built to overcome height differences between parts of a canal or river and meant to be a faster alternative to canal locks. Instead of the boat being driven on a platform along a railway-like path, the boat with surrounding water is enclosed by a gate and then pushed up or down a slope.

In practice, they proved to be very expensive and difficult to build, and to fail often. Only two were built in the world, both in France, replacing locks that allowed for a height difference of 13.3 and 13.6 m (43.6/44.6 feet) to be overcome.

The first one was the Montech water slope (first five images from the top) with sixteen tires at the Canal de Garonne in 1974 designed by Jean Aubert, the inventor of the modern water slope. It uses two large noisy engines, repurposed diesel locomotives (1985 horsepower in total), has a length of 443 m (1453 feet). Every boat passing through is supposed to be saving 45 minutes in comparison to the regular journey using the five local locks. However, it has been out of service for several years now, with repairs still not finished.

The Fonserannes water slope (the first and second image from the bottom) with eighteen tires at the Canal du Midi opened in 1984 with a length of 272 m (892 feet) and uses ten electric engines (1475 horsepower in total), a steel gantry and hydraulic transmission, but had to be closed just weeks after opening due to an accident and various issues regarding the hydraulic system and insufficient traction and was only re-opened in 1986, and then finally closed for good in 2001.

Read more:

Hans-Joachim Uhlemann: Canal lifts and inclines of the world (2002)

David Tew: Canal Inclines and Lifts (1984)

Permanent International Association of Navigation Congresses: Ship lifts: report of a Study Commission within the framework of Permanent Technical Committee I (1989)

Lionel Thomas Caswall Rolt: From Sea to Sea. The Canal du Midi (1973)

Lance Day, Ian McNeil, Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology (2003)

Inland Waterways International: Fonserannes water slope to be dismantled? (IWI News, June 2015)

Cyril J. Wood: Foreign Forays. Canals and Inland Navigations throughout the World

A. at Blogspot: The water slope at Montech (Travellingspouse.blogspot.com, June 16 2011)

Canaldumidi.bike: Fonserannes Water Slope in Beziers Canal Du Midi

Vanessa Couchman: The Water Slope at Montech: A Technical One-Off (11 July 2012)

Javier Irastorza Mediavilla: Montech water slope (Pente d’eau) at Canal du Midi (theblogbyjavier.com, July 17, 2015)

Video showing the Fonserannes water slope in use

Image sources:

Topmost image: Roehrensee, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: Profburp, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from top: Profburp, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Fourth image from top: Profburp, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Fifth image from top: Profburp, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from the bottom: Gloverepp, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottommost image: Gloverepp, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

More early experimental railcars: The Dringos propeller-locomotive

Built two years after the aerowagon in Berlin, Germany by the local engineer Otto Steinitz, the Dringos-Wagen (Dringos-Car) is another example of an early experimental railway car using propeller engines from aircraft as method of propulsion. It followed previous testing of an engine mount designed by Carl Geissen on existing railway cars on a special track of the German Aviation Research Institute (Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt), which were recorded as having reached speeds of up to 140 km/h (97 mph).

The Dringos-Car was based on a freight wagon and had two propellers, one on each end, with the cabin between the two. The engine, licensed from the Luftfahrt Company in Grunewald (a suburb of Berlin) had six cylinders and 160 horsepower, and according to a contemporary German general interest magazine the vehicle was in theory capable of speeds of up to 130 km/h, but a problem will likely have been the entirely free-standing engines that will have generated a lot of noise. A failed patent application in the UK from 1920 claimed that the installation of the engine as well as a later removal was simple and that it could be done on any wagon.

On its first trip on 11 May 1919 it carried 40 government railway officials, members of parliament, and crew members from Grunewald to the town of Beelitz, 40 km (25 miles) away. Unlike the previous test cars it proved to be much slower in practice, both in acceleration and top speed. It did not manage more than 60 km/h or 37 mph due to safety concerns regarding build quality and the brakes, and so there was no further interest in it.

This was compounded by Germany being forced to destroy its existing military aircraft and their parts that were enforced after WW 1, and so there were a lack of aircraft engines that could have been repurposed. However, Carl Geissen continued to work on railway cars with propellers in the early 1920s, and other engineers in later years also built several prototypes of propeller-locomotives. Steinitz fled Germany in 1939 and settled down in New York, where he died in 1964.

Read more:

Feòrag Forsyth: Otto Steinitz’s Dringos Propeller-locomotive (Forsyth's Compendium of Curious Contraptions, February 14, 2020)

Douglas Self: Propellor-Driven Locomotives. The Museum of RetroTechnology (2021)

William Pearce: Rail Zeppelin Propeller-Driven Railcar. Schienenzeppelin (OldMachinePress.com, 5 March 2021)

Worthpoint.com: Original antique press photo two German aero engine train Dringos locomotive

Patent application by Steinitz

Image sources:

Top: Photographic agency “Agence Rol”, Public Domain, via gallica.bnf.fr and William Pearce

Bottom: Photographic agency “Agence Rol”, Public Domain, via gallica.bnf.fr and William Pearce

0 notes

Photo

Brucks: the sporks among road vehicles

Brucks, combinations of buses and trucks also known as passenger freighters carrying both passengers and freight, have existed in different parts of the world for various reasons.

The topmost image shows a GN 101 built by Kenworth Motor Truck of Seattle, custom built for the Great Northern Railway to replace an unprofitable railway in the countryside of Montana. The bruck ran for 20 years between 1951 in 1971 between Whitefish and Kalispell about six times daily, and was able to carry 20 passengers and seven tons of freight with 220 horsepower. 11 other similar brucks were constructed, all used in Montana.

Already before that, brucks had however been built in Canada. New Flyer Industries of Winnipeg was the first company to do so in 1943 and can also be credited with the invention of the word. Like in the US, brucks in Canada were also popular as replacements for small railways as a more profitable means of transport. They were widely liked and many dozens were built and delivered to different clients.

The second image from top shows a simple bruck from the 1930s in Finland that operated on the Rovaniemi-Petsamo route. Between the world wars, brucks, known as seka-auto or “mix car” were used by transport companies, dairies and large farms.

The third image shows a model created by the Norwegian manufacturer Anco by modifying a 1937 Chevrolet, used on Langøya by the local transport agency. In Norway brucks have had a much more enduring popularity. In the 90s dozens were still in use, combining the functions of a regular bus, a school bus, and a truck transporting workers or freight on some routes in one vehicle. A typical kombinertbuss or kombibuss, as they are called in Norwegian (bokmål), could carry 25 passengers and 4,4 tons freight.

The fourth image shows an example of the mid-century Swedish variant of brucks. The pictured example is from 1965 and shows a vehicle based on a Mercedes-Benz LPO322, however the first brucks were in use as early as 1949 and played an important part when it came to transport in the northern part of the country. The mail service, having at that point been running the biggest regional bus line network for decades already, used them to transport more mailbags, packages in addition to regular passengers and workers.

Transport of goods was growing in the region in general, especially from farmers delivering their milk to large dairies, buses in the region (operated by the mail service) were often lengthened to be able to carry additional freight. These vehicles were called skvader, the name of a mythical winged hare that was first claimed to have been seen in 1874. However, when tank trucks began to be used in the 1970s, the skvader began to disappear. The last trip was made in June 2005.

The fifth image shows a modern-day Swedish bruck, a 2003 model from Helmark based on a Scania K124EB. The term now normally used is godsbuss or kombibuss. They are still used to carry freight in northern Sweden, and the service can be ordered online.

Read more:

RD McDonald: Great Northern's "Budd" (oil-electric.com, August 12, 2009)

Murray Lundberg: Canadian Coachways' Custom "Bruck" Bus-Truck (ExploreNorth.com)

Finn Borgen Førsund: Transport mellom fjordar. Firda billag 1920-1995 (1995, in Norwegian)

K8.se: Skvader '57 - Historien (in Swedish)

Erik Hamberg: Postens diligenstrafikunder 1900-talet (Postmuseum.se, 2004, in Swedish)

Alex Boese: The Tall-Tale Creature Gallery. Skavder (hoaxes.org)

Sundsvall Tidning: Sista rutten med mjölkbussen Skvadern gick i går (June 16, 2005, in Swedish)

Official website of a Swedish company offering freight transport using brucks (in Swedish)

Image sources, with additional information:

Topmost image: akampfer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: Unknown author, Public Domain, via the magazine Mobilisti 1/2009 and Wikimedia Commons

Third image from top: Alf Schrøder, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fourth image from top: Henrik Sendelbach, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottom image: Øyvind Berg, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gibraltar Airport: Where cars have to give way to planes

Other towns have railway crossings, Gibraltar has a runway crossing. The sole runway of the town under British administration crosses the sole road, the 4-lane Winston Churchill Avenue, that connects Gibraltar with Spain. It has to be closed every time a plane lands or takes off, which usually means ten minutes of interrupted traffic, but in some cases can also lead to wait times of up to two hours for cars, pedestrians, cyclists etc. on both sides.

The airport was first created as an emergency landing site for military aircraft, in 1939, and remains under control of the British Ministry of Defense to this day. Due to the small area of Gibraltar, 2.6 square miles or 6.5 km², of which a large amount is taken up by the famous Rock of Gibraltar with Europe’s only wild monkeys, there was no empty space left for an entire runway within city limits, and so it had to intersect with regular street traffic and be built where a horse racing circuit had previously existed. As a result, the airport is one of the few in the world located in walkable distance from a city center, being 500 m or 1640 feet from Gibraltar’s center away. The Spanish town across the border, La Linea de la Concepción is even closer, at a distance of 450 m (1476 ft).

The runway was later extended into the sea using material from the same Rock of Gibraltar and now measures 1,780 m (5,840 ft). A passenger terminal was constructed in 1959, but the airport was cleared for regular civil air traffic only in 1987 following an Airport Agreement between the UK and Spain. Direct connections between Gibraltar and Spain remained prohibited until 2006 with the adopting of a new agreement.

Despite the agreements, the entire airport and the land on which it is located, the 800 m long isthmus connecting the Gibraltar peninsula with Spain, remains subject to a dispute between the UK and Spain, with Spain claiming that it is not part of the town and castle of Gibraltar that was granted to Great Britain following the Treaty of Utrecht from 1713.

This has not stopped the growth of the airport, however, and a new, larger terminal was finished in 2012 to accommodate the increase in starts and landings. Plans for a street tunnel to end the unusual runway crossing also exist, but have not been realized yet.

More information:

Official website of the airport

Chloe Miller: An airport in Gibraltar has a busy 4-lane highway crossing through its runway (Insider.com, May 25, 2016)

Tom Boon: Gibraltar Airport – The Runway With A Road Crossing (Simpleflying.com, June 16, 2020)

Malagaweb.com: Gibraltar airport information

Travelbook.de: Gibraltar hat den wohl absurdesten Airport der Welt (10 September 2017, in German)

Daniel Boffey: EU angers UK with support for Spain's Gibraltar airport claims (The Guardian, 28 February 2019)

SkyVector: Gibraltar Airport

Digital copy of the 1987 Airport Agreement

Image sources:

Topmost image: Andrew Griffith, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from top: David Jones from Isle of Wight, United Kingdom, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from top: Ymnes, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fourth image from top, traffic running across the runway: Mike McBey, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Third image from the bottom, street traffic interrupted by a plane on the runway: Mike McBey, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second image from the bottom: Royal Air Force official photographer, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Map: Eric Gaba (Sting), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

3 notes

·

View notes