Text

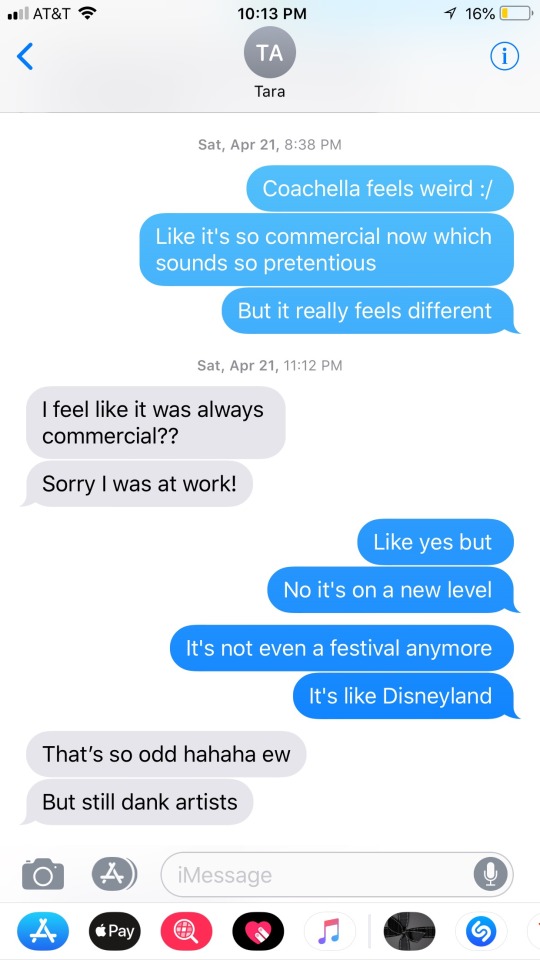

April 21st, 6:47 PM. VIP Rose Garden, Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival

Stranger: “Let’s just go to Beyoncé!”

Stranger’s friend: “It’s at 11—it starts in 5 hours, bro!”

This is a verbatim, firsthand account of a conversation I witnessed between two festival-goers, the Saturday of Weekend Two of Coachella. In case it wasn’t already apparent, these two men were overtly, outwardly bored (and bad at math, to boot).

Bored—yes, bored, of all possible states of being–at an event dedicated to hours upon hours, days upon days of what many would consider the antithesis of boredom: witnessing excellence in musical performance. To clarify the extent of the sheer ridiculousness and unsubstantiated nature of their boredom, between 6:47 PM and 11PM, any person at the festival had the option of seeing music icon David Byrne (frontman of Talking Heads as well as music novelist), R&B starlets Alina Baraz and Jorja Smith, hip-hop stars Tyler, The Creator, Post Malone, blackbear, or DJ duo Louis The Child, to name a few. Forgot to mention alt-rock heroes alt-J, and indie act Fleet Foxes, but hey, who’s counting?

…I’m counting.

Given that there were approximately, from what I heard, 110,000 people at Coachella that weekend, it makes sense that I didn’t happen upon these two individuals again. However, I did see a sea of others in the Beyoncé crowd. And there, now making me incredulous, I witnessed even more staunchly held, complete and utter boredom. Don’t believe me? Just watch.

youtube

Although, in a way, I have to write this for school, truthfully, overhearing this one interaction set a fire under me—regardless of whether I wrote this for class, or for its own sake, one way or another I needed for it to end up written by me and out there in the world. From my disappointing experience of Coachella 2018, and from the practically unanimous cacophony of opinion I hear from my friends and peers, it has become clear to me that, unfortunately, Coachella has become a hoax.

When I say “hoax”, I don’t mean to insinuate that the entire experience, or buying a ticket is a waste. In fact, I really enjoyed myself at some of the performances, but that’s because I genuinely wanted to go “for the music”—a phrase many people in my age group know, which itself is becoming a cliché; it’s some kind of necessary caveat to say “I’m not a total loser; I’m not a total follower”. Following the definition of a hoax: “a humorous or malicious deception”, there is a humorous, deceiving notion out there that going to Coachella is like going to some magic fountain—you get something from it that you don’t already have, and that you can’t get anywhere else. Legend has it, when you go to Coachella, you become christened by some magical, esoteric cool factor that drips down from the heavens and washes over you as soon as you walk through the gates.

Analyzing Coachella’s cool factor through all the years of its running is something that I don’t have the full capacity to do—I was three years old in 1999, its first year. That said, I have gone consecutively for the past five years, and I have gone in pretty much every way you can, with every kind of pass, backstage or GA, that you can have (practically the only thing I haven’t done is work there, but I have friends who have. That or camp, which I intend to do). For the record, my favorite year going was when I had a GA pass and crashed in my friend-of-friend’s hotel room that we invited ourselves to. In no way to brag, I’m a Coachella vet—all of this is just to establish to you, I know from experience and I have seen it over the years, Coachella is not what it used to be.

It’s not any secret that going to Coachella wasn’t always widely considered cool. In fact, for a time, it meant you were some kind of hippie-weirdo, which itself didn’t become cool or accepted into the mainstream for a while. For a time, the people who went to Coachella genuinely appreciated music enough to the point that they would haul themselves and all their crap out to the scorching desert, sleep in tents, not shower, etc…just so that they could have the chance to watch anyone from Prince to Bjork to Coldplay or Paul McCartney play. Certainly, there was a culture of escapism, as festival culture, travel, music, and drug use all tend to coexist. Clearly these former headliners are mainstream acts, but the appeal of the headliners isn’t actually the main concern here; it’s the act of actually going. I have sat in traffic longer than 7 hours getting home from Coachella (I have learned that the only way to do it is drive out Friday morning, miss a few acts, leave Sunday night after the headliner, otherwise you’re screwed), but, point being, the process of actually coming and going from Coachella is strenuous, at best.

The point I’m making here is not that the artists on the lineups of recent years are somehow worse, or that the people attending the festival are somehow worse, but rather, that the incentive to actually go to Coachella is not the same one that drew the initial Coachella-goers to the festival in earlier years. Somewhere along the line, being a hippie, smoking weed, wanting to re-create Woodstock, but in California (down to the fringe and feathers) became accepted, in fact sought-after, by mainstream culture, instead of ridiculed. Somewhere along the line, Coachella became the place to be, instead of the place to make fun of people for being at. And from my personal take, this year, Coachella has become a place (instead of one I used to beg my parents to let me go to in high school) I am unsure if I have the same love for, because the face of the festival has morphed into a caricature of itself: something I do not recognize, and not the event I fell in love with.

How did this happen?

In Malcolm Gladwell’s 1997 piece, “The Cool Hunt”, he writes about diffusion theory and how it relates to the proliferation and then eventual death of “cool” things; trends. Cool things make their way through five different groups of people: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards (Gladwell, 365). Innovators are the “handful” of innovative, creative-thinking people who start doing a certain thing, in spite of the fact that no one else is doing it, or it’s not widely considered cool (actually, perhaps for that very reason) (Gladwell, 365). Then, “early adopters” are “the slightly larger group that follow[s] them…the opinion leaders in the community, the respected, thoughtful people who watched and analyzed what those wild innovators were doing and did it themselves” (Gladwell, 365). Then comes the “early majority” and the “late majority”, “which is to say the deliberate and the skeptical masses, who would never try anything until the most respected [people] had tried it. Only after they had been converted [do] the ‘laggards’, the most traditional of all, follow suit” (Gladwell, 365).

Gladwell’s articulation of these five different groups has important relevance to the evolution of Coachella, following the story I just previously told. My argument would be that we are getting to the point where even the laggards are considering or attending Coachella, and at that point, the thing that is going through this cycle stops being cool. As Gladwell perfectly puts it:

“This is the first rule of cool: The quicker the chase, the quicker the flight. The act of discovering what’s cool is what causes cool to move on, which explains the triumphant circularity of coolhunting. Because of coolhunters…cool changes more quickly, and because cool changes more quickly, we need coolhunters” (Gladwell, 361)

This piece was written in 1997—that’s 21 years ago. The term “coolhunting” sounds a little anachronistic today. But if we put this formulation into 2018 terminology, a coolhunter would actually be not far off from what we have come to know as an influencer. And, with what application do we associate the term influencer?

Instagram.

Adorno and Horkheimer wrote: “real life is becoming indistinguishable from the movies” (8). This was back in 1944, when movies, and television programs, were the only sources of visual media entertainment available to consumers. The screens that “the movies” were shown on—in theaters, or on television—were the only screensthat existed for accessing entertainment media. In 2018, screens are ubiquitous to the point that going through one’s day without looking at one or touching one is inconceivable. Due to the proliferation of social media, the line between what constitutes entertainment and what constitutes real life has blurred substantially—it is virtually non-existent. Instead of merely receiving a broadcast or a piece of content as one would in the days of Adorno and Horkheimer, people today are both sources and receivers: the mediation of the self and one’s experiences is truly for the sake of, if we are to break it down, entertaining oneself by subjecting oneself to the appraisal of the value of their experiences, physical appearance, and worldview. The entertainment value comes from playing this game of chance, turning other people’s approval into quantifiable “likes”. It is important to recognize that the slot machine, dopamine-hit psychology of Instagram has become “indistinguishable” from our interactions with others and our social worlds—it has become, in this postmodern way, the way to interact with others.

Getting back to the five groups Gladwell defined, and the cycling-through of “cool” things, he notes that “the critical thing about this sequence is that it is almost entirely interpersonal” (361). Given that social media has completely altered the ways in which people interact with one another, and also that it is image-driven, time-sensitive and in some ways espouses a culture of competition…if we look at Instagram as the main source of interpersonal connection for people today, it makes sense to argue that, through Instagram, we come to understand what is cool, and what is not. In fact, the cycle of cool, which is already inherently quick (i.e. as Gladwell said, “the quicker the chase, the quicker the flight”) is expedited by the nature of this application. If Kendall Jenner wears something one day, she won’t wear it the next month, because everyone else will be wearing it and it won’t be cool anymore (she might not even wear it the next day). Gladwell’s 1997 formulation and understanding of coolhunters can be seen, in 2018, as a version of itself on steroids, taking the form of influencers. Adorno and Horkheimer’s 1944 conception of life being “indistinguishable from the movies” is on steroids because of Instagram.

It is my contention that the experience of Coachella has been fundamentally altered in direct relationship and correlation with the way in which Instagram has fundamentally altered the human experience of reality. As Instagram grows, and blurs the line between entertainment and reality, between entertainment and socializing, it becomes more and more a way in which people self-identify, and seek to perform an identity of themselves which will give them social status and indicate that they have a certain kind of cultural capital. The effects of this influence are so profound that people would rather experience Coachella through their phones, for Instagram, standing still (because of course, that would ruin the videos they would make for their Insta story) than experience the excellence in music performance that is before them, through their own eyes.

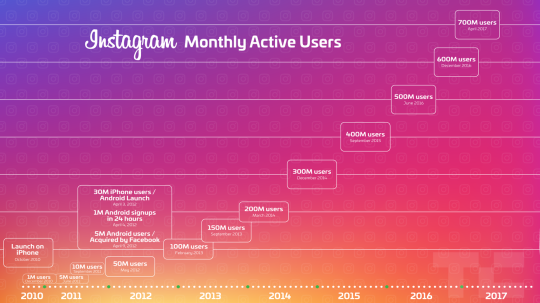

It is worthwhile to note that Instagram has grown astronomically since its launch in 2010; in 2017, Instagram had “doubled its user base to nearly 700 million actives in two years” (Constine)

Image via TechCrunch

The first year I had attended Coachella was 2014. As you can see from the graph, in 2014 Instagram had only 200M active users versus last year’s 700M; in 2018 it’s an estimated 800M.

The effects of the proliferation of Instagram upon culture have been profound; this does not necessarily require to be demonstrated by research, as it is something people in today’s society can feel. In the same way, one can feel a difference in the culture of Coachella from attending it year-to-year.

The ways in which Coachella has evolved have been numerous, but most relevant to this analysis is that what draws people to Coachella is not the desire to experience an impressive collection of live music–clearly, as the leading quotation and video in this piece’s introduction serve to demonstrate–but the social and cultural capital that go along with being a Coachella-goer. Fitting with Gladwell’s argument, as the festival becomes bigger and bigger--increasing their ticket cap past 125,000 people; booking arguably the most mainstream headliners in the history of the festival, accepting endorsements from massive retailers--the “coolness” of the festival depletes, and the overall experience of going to the festival changes drastically. What once made Coachella cool was that it served as an escape from the outside world of capitalist commercial crap, but as soon as you plop an an H&M store, or a Sephora tent, or a Shake Shack into the middle of the festival, it really just creates the experience of walking through a mall. There is no escape from commercial reality, which was once a draw for attending this kind of festival.

However, no matter how pure the festival were to be in this way, escaping capitalism is impossible in America. Adorno and Horkheimer write, “under monopoly all mass culture is identical, and the lines of its artificial framework begin to show through. The people at the top are no longer so interested in concealing monopoly: as its violence becomes more open, so its power grows. Movies and radio need no longer pretend to be art. The truth that they are just business is made into an ideology in order to justify the rubbish they deliberately produce” (4-5). This relates to the evolution of Coachella into an arena for making profit and receiving major corporate sponsorship because it demonstrates (which is the central argument of Adorno and Horkheimer’s piece) that culture industries really are not as noble as they seem; any kind of cultural experience or product exists in a capitalist system, and thus the experience of escape is really a trap in and of itself.

Now that Coachella is not an escape it has become more so a destination or a photo-op, a shopping mall for social validation, which actually changes the entire culture of the festival. Though one would need to attend the festival to truly get a feel for how things are, the effects of the proliferation of Instagram can be measured through looking at the crowds and seeing the number of cell phones. This shift is easily observable through the photographs in Coachella’s archive of past festivals. Looking at the crowds at Coachella, rather than at the performers, one can observe clearly that the experience of Coachella was once very different than it has become.

Coachella 2012, images via Coachella.

Through looking through Coachella’s archives of photos on their official website, in the “history” section, I sought to contrast the earliest and the latest sets of photos they had available. In the two photos above from Coachella 2012, one can see the crowds are small; in the first photo no one has a phone or a camera up; in the second they do, however, you can also see handheld videocameras, indicating that the reason people are documenting their experiences is because they personally want to have a record of it, not because they need to instantly broadcast it. Referring again to the graph, Instagram had only 50M users at this point. At that time, Coachella had sold out in record time and in record numbers, and there were 80,000-85,000 people in attendance.

Coachella 2017, image via Coachella.

The contrast between the crowds and the culture of the festival five years later is clear even from just four photographs. In the first of this set, people’s phones are hanging out of their hands, there is a girl taking a selfie on someone’s shoulders, people are reaching to take photos even though they are already close to the front. In the second image, you can faintly see the glow of cell phones from hands reaching upward in the crowd. I actually went to this set and couldn't get in because it was so crowded; I remember seeing this. At this point, Instagram has 700M active users, which is fourteen times what it was in 2012. For context, 700M is two times the population of the U.S, and the population of the U.S. is 6.5 times bigger than the 50M users of 2012.

From both my experience and my analysis of these images, it is clear that documenting Coachella may once have been for the personal appreciation and memories that one would have, but keeping in mind the astronomical growth and influence of Instagram, it is clear that there is a relationship here that has caused huge change. People are going to Coachella not to say they went, but to show they went, or are there, in real time. But now, the late majority and laggards who are there don’t know what to do with themselves for the four hours before their über-mainstream headliner takes the stage. The festival’s culture has drastically changed as a result, and in my opinion, is no longer even “cool”. But as Gladwell demonstrates, this is how it goes.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor, and Max Horkheimer. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” The Consumer Society Reader, The New Press, 2000, pp. 3–19.

Aslam, Salman. “Instagram by the Numbers (2018): Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts.” Omnicore, 11 Feb. 2018, www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/. Constine, Josh. “Instagram's Growth Speeds up as It Hits 700 Million Users.” TechCrunch, TechCrunch, 26 Apr. 2017, techcrunch.com/2017/04/26/instagram-700-million-users/.

Bain, Katie. “Has Coachella Gotten Too Crowded?” L.A. Weekly, 14 Sept. 2017, www.laweekly.com/music/coachella-2017-was-way-too-crowded-8138669.

Flynn, John, et al. “Coachella 2012 Sets Attendance Record.” Consequence of Sound, Consequence of Sound, 19 Apr. 2012, consequenceofsound.net/2012/04/coachella-2012-sets-attendance-record/.

Gladwell, Malcolm. “The Coolhunt.” The Consumer Society ReaderThe New Press, 2000, pp. 360–374.

“'Photo Gallery | Coachella 2018'.” Coachella, www.coachella.com/history/gallery/.

Rockwell, John. “David Byrne's 'How Music Works'.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Sept. 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/09/23/books/review/david-byrnes-how-music-works.html.

0 notes