Emily, Adam, And Callie's Anthology Project for English 276. Please see the Table of Contents to begin.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Against Women Unconstant, Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer was an English poet and writer of The Canterbury Tales. The language he wrote in was fairly close to modern English but he wrote in the common English of the time. This has lead to recent editions of his work having the spelling modernized for ease of use. The following selection is a short poem that is generally agreed by scholars to be written by him although in manuscripts featuring it his name is not present. The poem is a complaint against the inconstancy of women and features most of the original spellings in the text. Although the spelling is not modernized there are word occurrences that match words in current use and a key repeating of lyric to enforce the supposed inconstancy of the woman he is addressing. This repeating phrase as well as historical examples of women choosing to not be constant informs Chaucer’s poem while also adding weight to the charge he puts on the unnamed woman he addresses.

Against Women Unconstant

Madame, for your newefanglenesse

Many a servaunt have ye put out of grace.

I take my leve of your unstedfastnesse,

For wel I wot, whyl ye have lyves space,

Ye can not love ful half yeer in a place,

To newe thing your lust is ay so kene.

In stede of (1)blew, thus may ye were al grene.

Right as a mirour nothing may impresse,

But, lightly as it cometh, so mot it pace,

So fareth your love, your werkes beren witnesse.

Ther is no feith that may your herte enbrace,

But as a wedercok, that turneth his face

With every wind, ye fare, and that is sene;

In sted of blew, thus may ye were al grene.

Ye might be shryned for your brotelnesse

Bet than (2)Dalyda, Creseyde or Candace,

For ever in chaunging stant your sikernesse;

That tache may no wight fro your herte arace.

If ye lese oon, ye can wel tweyn purchase;

Al light for somer (ye woot wel what I mene),

In stede of blew, thus may ye were al grene.

English writers of the time coded blue with faithfulness, green with the opposite

Old spelling of Delilah. As in the bible story Samson and Delilah

0 notes

Text

Vox Clamantis Book 4, John Gower

Another selection from Vox Clamantis taken from Book 4 of the work by John Gower discusses the poet’s view of monks and his opinions on these supposed men of God. Another side to this section of the poem is advice Gower has for monks to take. In the following selection he describes the deadly lure of women and how easily a monk could turn from God in a female’s presence. There is vivid imagery utilized in describing the magnetic pull of the feminine with Gower using imagery of fire and original sin to bring home the dangers to his mortal soul a monk faces when interacting with a woman. With the use of such stark imagery Gower builds up the frailness of male morality and in turn the frailness of church morals. In many ways Gower gives women intense power. It’s destructive power but power nonetheless. Modern readers might be put off by the way Gower describes the feminine but it’s an important piece of male religious perspective. It paints the feminine as all encompassing and irresistible. This is in stark contrast to the tenuous control a monk has over his urge to stray from their faith into sin. It’s an interesting choice but Gower is utilizing these religious parallels to craft a discussion of what a truly faithful monk is able to do.

Vox Clamantis, Book 4

Shun a woman's conversation, O holy man; beware lest you entrust yourself to a passion raging beyond control. For the mind which is allured and bound over by a woman's love can never reach the (1)pinnacle of virtue. Of what use is their prattling to you? If you come in as a monk, you will go away a foul adulterer. Unless you turn aside from the venomous serpent, you will be poisoned by her when you least expect. Every woman enkindles a flame of passion; if one touches her, he is burned instantly. >> note 10 If you ponder the (2)books of the ancients and the writings of the Church Fathers, you may grieve that even holy men have met with ruin in this way. Did not woman expel man from the seat of Paradise? And was she not the source of our death? The man who is a good shepherd should therefore be vigilant, and he should everywhere drive these rapacious she-wolves away from the monastery.

Heaven

The bible/holy texts

0 notes

Text

Vox Clamantis Book 1, John Gower

John Gower was an English poet and a close friend of Geoffrey Chaucer. He’s most known for his long poetry of which Vox Clamantis is a much discussed example. Gower particularly focused on political and moral themes throughout his work. Vox Clamantis is Gower’s account of the 1381 Peasant’s Rising and throughout the work he takes the side of aristocrats and condemns the actions of the peasant class. For a poem with such strong views it opens with a rich and happy scene: a spring day. Gower uses his intro to his long form poem to set the scene and also ease the audience into the work. The rich language and detailed accounting of the actions of spring with the breeding of animals, new vegetation, and soft breezes create a picture of a thriving English countryside. This imagery later serves as a counterpoint to his various indictments of classes of individual within English society. The fact he opens his series of indictments with such a rich and peaceful scene works to his advantage in that he uses an ideal image of England to draw the audience to the further discussion of what he views as faults in English society. This was a fiery personal account of an uprising but Gower used his stance as a poet to discuss the failings of common men and the future he feared if lawlessness like the revolt continued.

Vox Clamantis, Book 1

It happened in the fourth year of King Richard, when June claims the month as its own, that the moon, leaving the heavens hid its rays under the earth, and Lucifer the betrothed of Dawn arose. A new light arose from its setting. * * * (1)Phoebus glowed warm with new fire in the sign of Cancer. He fertilized, nourished, fostered, increased, and enriched all things, and he animated everything that land and sea bring forth. Fragrance, glory, gleaming light, splendor and every embellishment adorned his chariot.

Then everything flourished, and there was a new epoch of time, and the cattle sported wantonly in the fields. Then the land was fertile, then was the hour for the herds to mate, and it was then that the reptile might renew its sports. The meadows were covered with the bloom of different flowers, and the chattering bird sang with its (2)untutored throat. Then too the teeming grass which had long lain concealed found a hidden path through which it lifted itself into the gentle breezes.

Phoebus: the sun god or the sun

Untutored: informal or untrained

0 notes

Text

Pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Margery Kempe

Another selection from Margery Kempe’s The Book of Margery Kempe presents one of Kempe’s many pilgrimages. In Pilgrimage to Jerusalem she has an intense religious experience in which after following Jesus’ path to crucifixion she weeps as if she witnessed it and feels that pain clearly.These fits of tears and sympathetic pain follow her all through her journey back to England and onward. The fits cause those around her to fear she is being possessed or is otherwise ill but she welcomes the events since she believes they grant her higher contemplation and are God’s will. The descriptions of her experiences are intense but Kempe portrays her condition as wanted since she believes that God has chosen his servant to reach higher devotion through the experience. The imagery is sensuous but due to its more sombre subject there is less sexual charge to the descriptions instead there is focus on the higher religious experience pain can induce in an individual. This selection paired with the prior Kempe selection in this anthology paints an image of the duality of Margery Kempe’s inner religious experience. On the one hand she was deeply human, a woman grappling with natural sexual desire, her duties as a wife, and an irrepressible drive to bring herself closer to a divine purpose. This divine purpose was her other self a woman so driven by her faith that she would distance her husband and suppress her human needs all to reach near intimate union with God.

From The Book of Margery Kempe

[Pilgrimage to Jerusalem]

And so they went forth into the Holy Land till they might see Jerusalem. And when this creature saw Jerusalem, riding on an ass, she thanked God with all her heart, praying him for his mercy that like as he had brought her to see this earthly city Jerusalem, he would grant her grace to see the blissful city Jerusalem above, the city of Heaven. Our Lord Jesu Christ, answering to her thought, granted her to have her desire. Then for joy that she had and the sweetness that she felt in the dalliance of our Lord, she was in point to 'a fallen off her ass, for she might not bear the sweetness and grace that God wrought in her soul. The twain pilgrims of Dutchmen went to her and kept her from falling, of which the one was a priest. And he put spices in her mouth to comfort her, weening she had been sick. And so they helped her forth to Jerusalem. And when she came there, she said, "Sirs, I pray you be not displeased though I weep sore in this holy place where our Lord Jesu Christ was quick and dead."

Then they went to the Temple in Jerusalem, and they were let in that one day at (1)evensong time and they abide there till the next day at evensong time. Then the friars lifted up a cross and led the pilgrims about from one place to another where our Lord had suffered his pains and his passions, every man and woman bearing a wax candle in their hand. And the friars always as they went about told them what our Lord suffered in every place. And the foresaid creature wept and sobbed so plentivously as though she had seen our Lord with her bodily eye suffering his Passion at that time. Before her in her soul she saw him verily by contemplation, and that caused her to have compassion. And when they came up onto the Mount of Calvary she fell down that she might not stand nor kneel but wallowed and wrested with her body, spreading her arms abroad, and cried with a loud voice as though her heart should 'a burst asunder, for in the city of her soul she saw verily and freshly how our Lord was crucified. Before her face she heard and saw in her ghostly sight the mourning of our Lady, of St. John and of Mary Magdalene, and of many other that loved our Lord. And she had so great compassion and so great pain to see our Lord's pain that she might not keep herself from crying and roaring though she should 'a been dead therefore.

And this was the first cry that ever she cried in any contemplation. And this manner of crying endured many years after this time for aught that any man might do, and therefore suffered she much despite and much reproof. The crying was so loud and so wonderful that it made people astoned unless that they had heard it before or else that they knew the cause of the crying. Abd she had them so oftentimes that they made her right weak in her bodily mights, and namely if she heard of our Lord's Passion. And sometime when she saw the Crucifix, or if she saw a man had a wound or a beast, whether it were, or if a man beat a child before her or smote a horse or another beast with a whip, if she might see it or hear it, her thought she saw our Lord be beaten or wounded like as she saw in the man or in the beast, as well in the field as in the town, and by herself alone as well as among the people. First when she had her cryings at Jerusalem, she had them oftentimes, and in Rome also. And when she came home into England, first at her coming home it came but seldom as it were once in a month, sithen once in the week, afterward quotidianly, and once she had fourteen on one day, and another day she had seven, and so as God would visit her, sometime in the church, sometime in the street, sometime in the chamber, sometime in the field when God would send them, for she knew never time nor hour when they should come. And they came never without passing great sweetness of devotion and high contemplation. And as soon as she perceived that she should cry, she would keep it in as much as she might that people should not 'a heard it for noying of them. For some said it was a wicked spirit vexed her; some said it was a sickness; some said she had drunken too much wine; some banned her; some wished she had been in the haven; some would she had been in the sea in a bottomless boat; and so each man as him thought. Other (2)ghostly men loved her and favored her the more. Some great clerks said our Lady cried never so, nor no saint in Heaven, but they knew full little what she felt, nor they would not believe but that she might 'a abstained her from crying if she had wished.

Evensong: evening prayer

Ghostly men: could be reference to the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost

0 notes

Text

Eliduc, Marie De France

Marie de France was an accomplished poet and court writer of the Middle Ages. Remembered for her narrative poetry she wrote on subjects that in many ways were predecessors to Medieval romances. The Lay of Eliduc is the last and longest of de France’s lays (or rhymed tale of love). Following the adventures of the knight Eliduc and the love triangle between him and his wife and lover the piece uses romantic imagery to inform the trials of his infidelity. The following excerpt from The Lay of Eliduc is from the point in the poem where he has left his wife’s side to be in service to a king who is being besieged due to an outside king wanting his daughter as wife. The daughter, Guilliadon soon falls in love with the brave knight and he eventually returns her love. The excerpt extends through their meeting, falling in love, and swearing of oaths that they would meet again at a time chosen by Guilliadon. Marie de France’s dealing of Eliduc’s infidelity with tenderness and sensual imagery renders why the princess would fall in love with a stranger and Eliduc would be tempted to stray as reasonable conclusions. There is considerable heightened language and the exchanging of tokens calls to mind courtship rituals as well as the formalities of chivalric action. These elements render de France’s lay as an intriguing early example of Medieval romantic court writing.

ELIDUC (excerpt) by Marie de France, translated by Eugene Mason

Eliduc was not only a brave and wary captain; he was also a courteous gentleman, right goodly to behold.

That fair maiden, the daughter of the King, heard tell of his deeds, and desired to see his face, because of the good men spake of him. She sent her privy chamberlain to the knight, praying him to come to her house, that she might solace herself with the story of his deeds, for greatly she wondered that he had no care for her friendship. Eliduc gave answer to the chamberlain that he would ride forthwith, since much he desired to meet so high a dame. He bade his squire to saddle his destrier, and rode to the palace, to have speech with the lady. Eliduc stood without the lady's chamber, and prayed the chamberlain to tell the dame that he had come, according to her wish. The chamberlain came forth with a smiling face, and straightway led him in the chamber. When the princess saw the knight, she cherished him very sweetly, and welcomed him in the most honourable fashion. The knight gazed upon the lady, who was passing fair to see. He thanked her courteously, that she was pleased to permit him to have speech with so high a princess. Guillardun took Eliduc by the hand, and seated him upon the bed, near her side. They spake together of many things, for each found much to say. The maiden looked closely upon the knight, his face and semblance; to her heart she said that never before had she beheld so comely a man. Her eyes might find no blemish in his person, and Love knocked upon her heart, requiring her to love, since her time had come. She sighed, and her face lost its fair colour; but she cared only to hide her trouble from the knight, lest he should think her the less maidenly therefore. When they had talked together for a great space, Eliduc took his leave, and went his way. The lady would have kept him longer gladly, but since she did not dare, she allowed him to depart. Eliduc returned to his lodging, very pensive and deep in thought. He called to mind that fair maiden, the daughter of his King, who so sweetly had bidden him to her side, and had kissed him farewell, with sighs that were sweeter still. He repented him right earnestly that he had lived so long a while in the land without seeking her face, but promised that often he would enter her palace now. Then he remembered the wife whom he had left in his own house. He recalled the parting between them, and the covenant he made, that good faith and stainless honour should be ever betwixt the twain. But the maiden, from whom he came, was willing to take him as her knight! If such was her will, might any pluck him from her hand?

All night long, that fair maiden, the daughter of the King, had neither rest nor sleep. She rose up, very early in the morning, and commanding her chamberlain, opened out to him all that was in her heart. She leaned her brow against the casement.

"By my faith," she said, "I am fallen into a deep ditch, and sorrow has come upon me. I love Eliduc, the good knight, whom my father made his (1)Seneschal. I love him so dearly that I turn the whole night upon my bed, and cannot close my eyes, nor sleep. If he assured me of his heart, and loved me again, all my pleasure should be found in his happiness. Great might be his profit, for he would become King of this realm, and little enough is it for his deserts, so courteous is he and wise. If he have nothing better than friendship to give me, I choose death before life, so deep is my distress."

When the princess had spoken what it pleased her to say, the chamberlain, whom she had bidden, gave her loyal counsel.

"Lady," said he, "since you have set your love upon this knight, send him now—if so it please you—some goodly gift-girdle or scarf or ring. If he receive the gift with delight, rejoicing in your favour, you may be assured that he loves you. There is no Emperor, under Heaven, if he were tendered your tenderness, but would go the more lightly for your grace."

The damsel hearkened to the counsel of her chamberlain, and made reply,

"If only I knew that he desired my love! Did ever maiden woo her knight before, by asking whether he loved or hated her? What if he make of me a mock and a jest in the ears of his friends! Ah, if the secrets of the heart were but written on the face! But get you ready, for go you must, at once."

"Lady," answered the chamberlain, "I am ready to do your bidding."

"You must greet the knight a hundred times in my name, and will place my girdle in his hand, and this my golden ring."

When the chamberlain had gone upon his errand, the maiden was so sick at heart, that for a little she would have bidden him return. Nevertheless, she let him go his way, and eased her shame with words.

"Alas, what has come upon me, that I should put my heart upon a stranger. I know nothing of his folk, whether they be mean or high; nor do I know whether he will part as swiftly as he came. I have done foolishly, and am worthy of blame, since I have bestowed my love very lightly. I spoke to him yesterday for the first time, and now I pray him for his love. Doubtless he will make me a song! Yet if he be the courteous gentleman I believe him, he will understand, and not deal hardly with me. At least the dice are cast, and if he may not love me, I shall know myself the most woeful of ladies, and never taste of joy all the days of my life." Whilst the maiden lamented in this fashion, the chamberlain hastened to the lodging of Eliduc. He came before the knight, and having saluted him in his lady's name, he gave to his hand the ring and the girdle. The knight thanked him earnestly for the gifts. He placed the ring upon his finger, and the girdle he girt about his body. He said no more to the chamberlain, nor asked him any questions; save only that he proffered him a gift. This the messenger might not have, and returned the way he came. The chamberlain entered in the palace and found the princess within her chamber. He greeted her on the part of the knight, and thanked her for her bounty.

"Diva, diva," cried the lady hastily, "hide nothing from me; does he love me, or does he not?"

"Lady," answered the chamberlain, "as I deem, he loves you, and truly. Eliduc is no cozener with words. I hold him for a discreet and prudent gentleman, who knows well how to hide what is in his heart. I gave him greeting in your name, and granted him your gifts. He set the ring upon his finger, and as to your girdle, he girt it upon him, and belted it tightly about his middle. I said no more to him, nor he to me; but if he received not your gifts in tenderness, I am the more deceived. Lady, I have told you his words: I cannot tell you his thoughts. Only, mark carefully what I am about to say. If Eliduc had not a richer gift to offer, he would not have taken your presents at my hand."

"It pleases you to jest," said the lady. "I know well that Eliduc does not altogether hate me. Since my only fault is to cherish him too fondly, should he hate me, he would indeed be blameworthy. Never again by you, or by any other, will I require him of aught, or look to him for comfort. He shall see that a maiden's love is no slight thing, lightly given, and lightly taken again—but, perchance, he will not dwell in the realm so long as to know of the matter."

"Lady, the knight has covenanted to serve the King, in all loyalty, for the space of a year. You have full leisure to tell, whatever you desire him to learn."

When the maiden heard that Eliduc remained in the country, she rejoiced very greatly. She was glad that the knight would sojourn awhile in her city, for she knew naught of the torment he endured, since first he looked upon her. He had neither peace nor delight, for he could not get her from his mind. He reproached himself bitterly. He called to remembrance the covenant he made with his wife, when he departed from his own land, that he would never be false to his oath. But his heart was a captive now, in a very strong prison. He desired greatly to be loyal and honest, but he could not deny his love for the maiden—Guillardun, so frank and so fair.

Eliduc strove to act as his honour required. He had speech and sight of the lady, and did not refuse her kiss and embrace. He never spoke of love, and was diligent to offend in nothing. He was careful in this, because he would keep faith with his wife, and would attempt no matter against his King. Very grievously he pained himself, but at the end he might do no more. Eliduc caused his horse to be saddled, and calling his companions about him, rode to the castle to get audience of the King. He considered, too, that he might see his lady, and learn what was in her heart. It was the hour of meat, and the King having risen from table, had entered in his daughter's chamber. The King was at chess, with a lord who had but come from over-sea. The lady sat near the board, to watch the movements of the game. When Eliduc came before the prince, he welcomed him gladly, bidding him to seat himself close at hand. Afterwards he turned to his daughter, and said, "Princess, it becomes you to have a closer friendship with this lord, and to treat him well and worshipfully. Amongst five hundred, there is no better knight than he."

When the maiden had listened demurely to her father's commandment, there was no gayer lady than she. She rose lightly to her feet, and taking the knight a little from the others, seated him at her side. They remained silent, because of the greatness of their love. She did not dare to speak the first, and to him the maid was more dreadful than a knight in mail. At the end Eliduc thanked her courteously for the gifts she had sent him; never was grace so precious and so kind. The maiden made answer to the knight, that very dear to her was the use he had found for her ring, and the girdle with which he had belted his body. She loved him so fondly that she wished him for her husband. If she might not have her wish, one thing she knew well, that she would take no living man, but would die unwed. She trusted he would not deny her hope.

"Lady," answered the knight, "I have great joy in your love, and thank you humbly for the goodwill you bear me. I ought indeed to be a happy man, since you deign to show me at what price you value our friendship. Have you remembered that I may not remain always in your realm? I covenanted with the King to serve him as his man for the space of one year. Perchance I may stay longer in his service, for I would not leave him till his quarrel be ended. Then I shall return to my own land; so, fair lady, you permit me to say farewell."

The maiden made answer to her knight,

"Fair friend, right sweetly I thank you for your courteous speech. So apt a clerk will know, without more words, that he may have of me just what he would. It becomes my love to give faith to all you say."

The two lovers spoke together no further; each was well assured of what was in the other's heart. Eliduc rode back to his lodging, right joyous and content. Often he had speech with his friend, and passing great was the love which grew between the (2)twain.

Eliduc pressed on the war so fiercely that in the end he took captive the King who troubled his lord, and had delivered the land from its foes. He was greatly praised of all as a crafty captain in the field, and a hardy comrade with the spear. The poor and the minstrel counted him a generous knight. About this time that King, who had bidden Eliduc avoid his realm, sought diligently to find him. He had sent three messengers beyond the seas to seek his ancient Seneschal. A strong enemy had wrought him much grief and loss. All his castles were taken from him, and all his country was a spoil to the foe. Often and sorely he repented him of the evil counsel to which he had given ear. He mourned the absence of his mightiest knight, and drove from his councils those false lords who, for malice and envy, had defamed him. These he outlawed for ever from his realm. The King wrote letters to Eliduc, conjuring him by the loving friendship that was once between them, and summoning him as a vassal is required of his lord, to hasten to his aid, in that his bitter need. When Eliduc heard these tidings they pressed heavily upon him, by reason of the grievous love he bore the dame. She, too, loved him with a woman's whole heart. Between the two there was nothing but the purest love and tenderness. Never by word or deed had they spoiled their friendship. To speak a little closely together; to give some fond and foolish gift; this was the sum of their love. In her wish and hope the maiden trusted to hold the knight in her land, and to have him as her lord. Naught she deemed that he was wedded to a wife beyond the sea. "Alas," said Eliduc, "I have loitered too long in this country, and have gone astray. Here I have set my heart on a maiden, Guillardun, the daughter of the King, and she, on me. If, now, we part, there is no help that one, or both, of us, must die. Yet go I must. My lord requires me by letters, and by the oath of fealty that I have sworn. My own honour demands that I should return to my wife. I dare not stay; needs must I go. I cannot wed my lady, for not a priest in Christendom would make us man and wife. All things turn to blame. God, what a tearing asunder will our parting be! Yet there is one who will ever think me in the right, though I be held in scorn of all. I will be guided by her wishes, and what she counsels that will I do. The King, her sire, is troubled no longer by any war. First, I will go to him, praying that I may return to my own land, for a little, because of the need of my rightful lord. Then I will seek out the maiden, and show her the whole business. She will tell me her desire, and I shall act according to her wish."

The knight hesitated no longer as to the path he should follow. He went straight to the King, and craved leave to depart. He told him the story of his lord's distress, and read, and placed in the King's hands, the letters calling him back to his home. When the King had read the writing, and knew that Eliduc purposed to depart, he was passing sad and heavy. He offered the knight the third part of his kingdom, with all the treasure that he pleased to ask, if he would remain at his side. He offered these things to the knight—these, and the gratitude of all his days besides.

"Do not tempt me, sire," replied the knight. "My lord is in such deadly peril, and his letters have come so great a way to require me, that go I must to aid him in his need. When I have ended my task, I will return very gladly, if you care for my services, and with me a goodly company of knights to fight in your quarrels."

The King thanked Eliduc for his words, and granted him graciously the leave that he demanded. He gave him, moreover, all the goods of his house; gold and silver, hound and horses, silken cloths, both rich and fair, these he might have at his will. Eliduc took of them discreetly, according to his need. Then, very softly, he asked one other gift. If it pleased the King, right willingly would he say farewell to the princess, before he went. The King replied that it was his pleasure, too. He sent a page to open the door of the maiden's chamber, and to tell her the knight's request. When she saw him, she took him by the hand, and saluted him very sweetly. Eliduc was the more fain of counsel than of claspings. He seated himself by the maiden's side, and as shortly as he might, commenced to show her of the business. He had done no more than read her of his letters, than her face lost its fair colour, and near she came to swoon. When Eliduc saw her about to fall, he knew not what he did, for grief. He kissed her mouth, once and again, and wept above her, very tenderly. He took, and held her fast in his arms, till she had returned from her swoon.

"Fair dear friend," said he softly, "bear with me while I tell you that you are my life and my death, and in you is all my comfort. I have bidden farewell to your father, and purposed to go back to my own land, for reason of this bitter business of my lord. But my will is only in your pleasure, and whatever the future brings me, your counsel I will do."

"Since you cannot stay," said the maiden, "take me with you, wherever you go. If not, my life is so joyless without you, that I would wish to end it with my knife." Very sweetly made answer Sir Eliduc, for in honesty he loved honest maid,

"Fair friend, I have sworn faith to your father, and am his man. If I carried you with me, I should give the lie to my troth. Let this covenant be made between us. Should you give me leave to return to my own land I swear to you on my honour as a knight, that I will come again on any day that you shall name. My life is in your hands. Nothing on earth shall keep me from your side, so only that I have life and health."

Then she, who loved so fondly, granted her knight permission to depart, and fixed the term, and named the day for his return. Great was their sorrow that the hour had come to bid farewell. They gave rings of gold for remembrance, and sweetly kissed adieu. So they severed from each other's arms.

Seneschal: senior court appointment

Twain:old form of two

0 notes

Text

Showing Of Love, Julian of Norwich

Julian of Norwich was an English mystic and theologian who in the writing of Showing of Love became the first woman to write a theological text. The text is a description and rumination of the sixteen visions of Christ that came to her as she lay battling an intense illness. The selections that follow are a sampling of her thoughts on Christ, her dialogue with Christ’s messages to her, and her striving to explain the truth’s she believed were revealed to her. In the And in this he showed me a little thing showing, a hazelnut is used to illuminate God’s intent and quality. In the showing God, for your goodness God’s requirements of humanity are explored. Both showings utilize a set of three qualities and portray the dialogue between God and Julian with an unusual amount of sensuality. This sensuality is in many ways tied to her positive outlook on the divine and her ideas of divine love. Julian’s concept of divine love encompassed all aspects of familial love in the belief that God’s interactions with humanity mirrored and exceeded the love humanity experienced with family connections. There are also mildly existential threads present in her writings that combined with the theological create a complex picture of religious experience that have been seldom matched. Julian of Norwich was alive during Margery Kempe’s time but by investigating their individual experiences with religion and their concepts of the divine modern readers can view a fuller image of early female religious experience.

Selections from The Westminster Cathedral/Abbey Manuscript

And in this he showed me a little thing, the quantity of a hazel nut , lying in the palm of my hand, as it seemed. And it was as round as any ball. I looked upon it with the eye of my understanding, and thought, 'What may this be?' And it was answered generally thus,'It is all that is made.' I marvelled how it might last, for I thought it might suddenly have fallen to nought for littleness. And I was answered in my understanding: It lasts and ever shall, for God loves it. And so have all things their beginning by the love of God.

In this little thing I saw three properties. The first is that God made it. The second that he loves it. And the third, that God keeps it. But what is this to me? Truly, the Creator, the Keeper, the Lover. For until I am substantially oned to him, I may never have full rest nor true bliss. That is to say, until I be so fastened to him that there is nothing that is made between my God and me.

This little thing that is made, I thought it might have fallen to nought for littleness. Of this we need to have knowledge that it is like to nought, all things that are made. For to love and have God that is unmade.

For this is the cause why we are not at ease in heart and soul, for we seek rest here, in this thing that is so little where there is no rest, and knowing not our God who is all mighty, all wise and all good. For he is true rest. God will be known, and he likes us to rest in him. For all that is beneath him cannot suffice us. And this is the cause why no soul is rested, until it is noughted of all that is made. And when he wills to be noughted for love, to have him who is all, then he is able to receive spiritual rest.

Also our Lord showed that it is the fullest pleasure to him, that an innocent soul come to him nakedly, plainly and humbly. For this is the natural yearning of the soul by the touching of the Holy Spirit. And by the understanding that I have in this showing,

'God, for your goodness, give me yourself. For you are enough for me and I may not ask anything that is less, that may be fully worthy of you. And if I ask any thing that is less, I am always wanting. But only in you I have all.' And these words, 'God of your goodness' , are most lovely to the soul, and full nigh touching the will of our Lord. For his goodness comprehends all his creation and all his blessed works and overpasses them without end. For he is the endlessness, and he has made us only for himself, and restored us by his precious Passion, and ever keeps us in his blessed love, and all this is of his goodness. This Showing was given, as to my understanding, to teach our souls wisely to cleave to the goodness of God.

It is God's will that we have three things in our seeking of his gift. The first is, that we seek willingly and busily without sloth, as it may be with his grace gladly and merrily, without (1)unskilfull heaviness and vain sorrow. The second, that we abide with him steadfastly for his love, without complaining and striving against him to our lives' end, for it shall last only a while. The third is that we trust in him mightily with a fully sure faith, for it is his will that we shall know that he will appear suddenly and blessedfully to all his lovers, for his working is secret, and it will be perceived, and his appearing shall be swift and sudden, and he will be believed, for he is very able, humble and courteous, blessed must he be.

After this, I saw God in a point. That is to say in my understanding. But which sight I saw that he is all things. I beheld with advisement, seeing and knowing in that sight, that he does all that is done, be it never so little. And I saw that nothing is done by chance, nor by hazard, but all by the foreseeing of God's wisdom. And if it be chance or fortune in the sight of man, our blindness and our lack of foresight is the cause. Therefore, well I know that in sight of our lord God, there is not chance or happenstance. And therefore it needs behoove me to grant that all things that are done, are well done, because our lord God does all. For in this time the working of Creation was not showed but of our lord God, in Creation, (2)for he is in the midpoint of all things, and he does all.

Unskilfull: old form of unskilled

God is the wellspring of humanities experiences

0 notes

Text

Margery Kempe and Her Husband Reach A Settlement, Margery Kempe

Margery Kempe was a Christian mystic who dictated her visions and spiritual experiences in a self titled autobiography, The Book of Margery Kempe. Considered by some circles to be the first autobiography it is also unique in being one of the few documents to give insight into the female experience of a middle class woman in Medieval times. Following Kempe early in her marriage and the birth of her first child, through pilgrimages, and her tribulations in attaining a sexless marriage the text offers an extensive account of her life.

Another attribute of her book is extensive and surprisingly frank discussions of Margery’s sexual appetites, thoughts, and seeking of near sexual union with Christ. She was a married woman and had many children but the level of sexual frankness displayed in the writing can be surprising at first. An example of this frankness is shown in the the following excerpt Margery and Her Husband Reach a Settlement. Detailing the discussion between Margery and her husband as they travel they discuss the state of their relationship and the toll of being abstinent from sexual activity. They have been abstinent for three years but Margery still craves intimacy from her husband and she questions why he has not tried to make her do her wifely duty when they share a bed. The discussion that comes from this goes back and forth between Margery and her husband and internally her discussion and vision of God in their travels.

[Margery and Her Husband Reach a Settlement]

It befell upon a Friday on Midsummer Even in right hot weather, as this creature was coming from York-ward bearing a bottle with beer in her hand and her husband a cake in his bosom, he asked his wife this question: "Margery, if there came a man with a sword and would smite off my head unless that I should commune kindly with you as I have done beofre, say me truth of your conscience - for ye say ye will not lie - whether would ye suffer my head to be smit off or else suffer me to meddle with you again as I did sometime?" "Alas, sir," She said, "why move ye this matter and have we been chaste this eight weeks?" "For I will wit the truth of your heart." And the she said with great sorrow, "Forsooth, I had liefer see you be slain than we should turn again to our uncleanness." And he said again, "Ye are no good wife."

And then she asked her husband what was the cause that he had not meddled with eight weeks before, sithen she lay with him every night in his bed. And he said he was so made afeared when he would 'a touched her that he durst no more do. "Now, good sir, amend you and ask God mercy, for I told you near three year sithen that ye should be slain suddenly, and now is this the third year, and yet I hope I shall have my desire. Good sir, I pray you grant me that I shall ask, and I shall pray for you that ye shall be saved through the mercy of our Lord Jesu Christ, and ye shall have more meed in Heaven than if ye wore a hair or a habergeon. I pray you, suffer me to make a vow of chastity in what bishop's hand that God will." "Nay," he said, "that will I not grant you, for now I may use you without deadly sin and then might I not so." The she said again, "If it be the will of the Holy Ghost to fulfill that I have said, I pray God ye might consent thereto; and if it be not the will of the Holy Ghost, I pray God ye never consent thereto."

Then they went forth to-Bridlington-ward in right hot weather, the foresaid creature (1) having great sorrow and great dread for her chastity. And as they came by a cross, her husband set him down under the cross, cleping his wife unto him and saying these words unto her, "Margery, grant me my desire, and I shall grant you your desire. My first desire is that we shall lie still together in one bed as we have done before; the second that ye shall pay my debts ere ye go to Jerusalem; and the third that ye shall eat and drink with me on the Friday as ye were wont to do." "Nay sir," she said, "to break the Friday I will never grant you while I live." "Well," he said, "then shall I meddle with you again."

She prayed him that he would give her leave to make her prayers, and he granted it goodly. Then she knelt down beside a cross in the field and prayed in this manner with great abundance of tears, "Lord God, thou knowest all thing; thou knowest what sorrow I have had to be chaste in my body to thee all this three year, and now might I have my will and I dare not for love of thee. For if I would break that manner of fasting which thou commandest me to keep on the Friday without meat or drink, I should now have my desire. But, blessed Lord, thou knowest I will not contrary to thy will, and mickle now is my sorrow unless that I find comfort in thee. Now, blessed Jesu, make thy will known to me unworthy that I may follow thereafter and fulfil it with all my might." And then our Lord Jesu (2) Christ with great sweetness spoke to this creature, commanding her to go again to her husband and pray him to grant her that she desired, "And he shall have that he desireth. For, my dearworthy daughter, this was the cause that I bade thee fast for thou shouldest the sooner obtain and get thy desire, and now it is granted thee. I will no longer thou fast, therefore I bid thee in the name of Jesu eat and drink as thy husband doth."

Then this creature thanked our Lord Jesu Christ of his grace and his goodness, sithen rose up and went to her husband saying unto him, "Sir, if it like you, ye shall grant me my desire and ye shall have your desire. Granteth me that ye shall not come in my bed, and I grant you to quit your debts ere I go to Jerusalem. And maketh my body free to God so that ye never make no challenging in me to ask no debt of matrimony after this day while ye live, and I shall eat and drink on the Friday at your bidding." Then said her husband again to her, "As free may your body be to God as it hath been to me." This creature thanked God greatly, enjoying that she had her desire, praying her husband that they should say three Pater Noster in the worship of the Trinity for the great grace that he had granted them. And so they did, kneeling under a cross, and sithen they ate and drank together in great gladness of spirit. This was on a Friday on Midsummer Even.

1. Creature: Margery’s referring to herself as a creature could be seen as her saying she is a creature of God or rather created by God

2. Jesu: Older form of Jesus

0 notes

Text

Romance, Gender, & Sexuality In The Middle Ages

Although the study of gender and sexuality is relatively young in comparison to other academic studies it’s a rich topic that extends into almost every aspect of the human experience. Keeping this in mind the authors of this anthology have set out to explore an era that the general public might not think would be ripe for sexual studies: The Middle Ages. In the course of the research for this anthology it became clear that any ideas that early eras were more sexually closeted were gross misconceptions and instead by looking at the literature from the era it could be construed that sexuality and gender norms were more open than previously thought. In this vein the contributors of this work have sought to present literary texts that provide clear examples of Medieval explorations of sexuality, sensuality, and gender. These texts are dynamic enough to pique the interest of a general audience but are also curated enough to satisfy regular readers of Medieval writing. Keeping these dual audiences in mind the author’s have decided to debut this volume online through Tumblr to allow discussion among readers and denizens of the internet to learn and comment.

0 notes

Text

I Sing of a Maiden

I Sing of a Maiden is a medieval lyric about the virgin mother of Jesus Christ, Mother Mary. Most writings during this period directly pertained to religious material, and the lyrics were no different. This particular lyric sings of Mother Mary, and how elegant and serene she is. There is a fair amount of nature symbolism in this lyric too, as the impregnation of Mary is compared to a drop of dew from spring’s showers. She gives life to the growing Earth, and to Jesus himself, who ensure eternal life for so many. Her virginity and purity is referenced all throughout as well, as the line “he cam also stille” can be read as the seed of life came to her divinely.

The last stanza of I Sing of a Maiden heralds the virgin Mother Mary, and exalting how great a woman she must be to be lucky enough to birth the son of king of the heavens. This shows us some of the virtues that were valued during this time period, as the Mother Mary is clearly portrayed as role model not only for women but also for men. Mother Mary seems to be the standard at which a woman should be judged; she should be commandingly sublime through graceful purity. This is unfair, however, for women to be judged against the Mother Mary, which also can be read as a reality vs. expectation issue for medieval era women.

I sing of a maiden

That is makelees (1):

King of alle kinges

To her sone she chees.

He cam also stille

Ther his moder was

As dewe in Aprille

That falleth on the gras.

He cam also stille

To his modres bowr

As dewe in Aprille

That falleth on the flowr.

He cam also stille

Ther his moder lay

As dewe in Aprille

That falleth on the spray (2).

Moder and maiden

Was nevere noon but she:

Wel may swich a lady

Godes moder be.

1. Mateless; alludes to the immaculate conception

2. The escalation from grass to flower to spray coincides with the stages of pregnancy

0 notes

Text

How the Goode Wife Taught Hyr Doughter

How the Goode Wife Taught Hyr Doughter is a medieval conduct poem that directly addresses medieval women, something that was very rare for this time period. The speaker of this poem can be read as either a literal mother or an elder, either way, the target audience is for younger women. One of the primary virtues preached in this poem is honor. Honor encompasses a lot in this poem, as honor applies not only to honoring one’s religion but also honoring their husbands/men. Both of these are normative for the time period, as religion was massively influential at the time as it was the primary subject of most writings, and women submitting to men was a big portion of marital life.

The other virtue discussed in How the Goode Wife Taught Hyr Doughter is prosperity, and that is in reference to one’s appearance in public and in status. The speaker tells its’ audience to be prudent when it comes to men by that one shouldn’t accept too many gifts from men or to be seen with different men out in public. The prosperity of “wealth” alludes to making economically wise decisions, which was something that garnered status in itself in the medieval era.

Another interesting component of this poem that is being preached is it tell the young women to be nice to the other women of the house, presumably meaning the “help”. This provides interesting insight into the workings of the different classes, especially considering that the speaker is advocating for treating them nicely, or at least marginally so.

Lyst and lythe a lytell space,

Y schall you telle a praty cace,

How the gode wyfe taught hyr doughter

5 To mend hyr lyfe, and make her better:

"Doughter, and thou wylle be a wyfe,

Wysely to wyrche in all thi lyfe

Serve God, and kepe thy chyrche,

And myche the better thou shalt wyrche.

10 To go to the chyrch, lette for no reyne,

And that schall helpe thee in thy peyne.

Gladly loke thou pay thy tythes,

Also thy offeringes loke thou not mysse;

Of pore men be thou not lothe,

15 Bot gyff thou them both mete (1) and clothe;

And to pore folke be thou not herde,

Bot be to them thyn owen stowarde;

For where that a gode stowerde is,

Wantys seldome any ryches.

20 When thou arte in the chyrch, my chyld,

Loke that thou be bothe meke and myld,

And bydde thy bedes aboven alle thinge,

With sybbe ne fremde make no jangelynge.

Laughe thou to scorne nother olde ne yonge,

25 Be of gode berynge and of gode tonge;

Yn thi gode berynge begynnes thi worschype,

My dere doughter, of this take kepe.

Yf any man profer thee to wede,

A curtas answer to hym be seyde,

30 And schew hym to thy frendes alle;

For any thing that may befawle,

Syt not by hym, ne stand thou nought

Yn sych place ther synne mey be wroght.

What man that thee doth wedde with rynge,

35 Loke thou hym love aboven all thinge;

Yf that it forteyne thus with thee

That he be wroth, and angery be,

Loke thou mekly answere hym,

And meve hym nother lyth ne lymme;

40 And that schall sclake hym of hys mode

Than schall thou be hys derlynge gode.

Fayre wordes wreth do slake;

Fayre wordes wreth schall never make,

Ne fayre wordes brake never bone,

45 Ne never schall in no wone.

Be fayre of semblant, my dere doughter,

Change not thi countenans with grete laughter

And wyse of maneres loke thou be gode,

Ne for no tayle change thi mode

50 Ne fare not a thou a gyglot were,

Ne laughe thou not low, be thou therof sore.

Luke thou also gape not to wyde,

For anythinge that may betyde.

Suete of speche, loke that thow be

55 Trow in worde and dede; lerne thus of me.

Loke thou fle synne, vilony, and blame,

And se ther be no man that seys thee any schame.

When thou goys in the gate, go not to faste,

Ne hyderwerd ne thederward thi hede thou caste.

60 No grete othes loke thou swere:

Byware, my doughter, of syche a maner!

Go not as it wer a gase

Fro house to house, to seke the mase

Ne go thou not to no merket

65 To sell thi thryft, bewer of itte.

Ne go thou nought to the taverne,

Thy godnes for to selle therinne;

Forsake thou hym that taverne hanteth,

And all the vices that therinne bethe.

70 Wherever thou comme at ale other wyne,

Take not to myche, and leve be tyme;

For mesure therinne, it is no herme,

And drounke to be, it is thi schame.

Ne go thou not to no wrastylynge,

75 Ne git to no coke schetynge,

As it wer a strumpet other a gyglote,

Or as a woman that lyst to dote.

Byde thou at home, my doughter dere.

Thes poyntes at me I rede thou lere,

80 And wyrke thi werke at nede,

All the better thou may spede

Y swere thee, doughter, be heven Kynge,

Mery it is of althynge.

Aquyente thee not with every man.

85 That inne the stret thou metys than;

Thof he wold be aqueynted with thee,

Grete hym curtasly, and late hym be.

Loke by hym not longe thou stond,

That thorow no vylony thi hert fond

90 All the men be not trew

That fare spech to thee can schew.

For no covetys no giftys thou take,

Bot thou wyte why: sone them forsake.

For gode women, with gyftes

95 Me ther honour fro them lyftes,

Thofe that thei wer all trew

As any stele that bereth hew,

For with ther giftes men them over gone.

Thof thei wer trew as ony stone,

100 Bounde thei be that giftys take:

Therfor thes giftes thou forsake.

Yn other mens houses make thou no maystry;

For drede, no vylony to thee be spye.

Loke thou chyd no wordes bolde,

105 To myssey nother yonge ne olde

For and thou any chyder be,

Thy neyghbors wylle speke thee vylony.

Be thou not to envyos,

For dred thi neyghbors wyll thee curse,

110 Envyos hert hymselve fretys,

And of gode werkys hymselve lettys.

Houswyfely wyll thou gone

On werke deys in thine awne wone.

Pryde, rest, and ydellschype,

115 Fro thes werkes thou thee kepe;

And kepe thou welle thy holy dey,

And thy God worschype when thou may,

More for worschype than for pride;

And styfly in thy feyth thou byde.

120 Loke thou were no ryche robys;

Ne counterfyte thou no ladys

For myche schame do them betyde

That lese ther worschipe thorow ther pride.

Be thou, doughter, a houswyfe gode,

125 And evermore of mylde mode.

Wysely loke thi hous and meneye,

The beter to do thei schall be.

Women that be of yvell name,

Be ye not togedere in same

130 Loke what moste nede is to done.

And sette thi mené therto ryght sone.

That thinge that is before done dede,

Redy it is when thou hast nede.

And if thy lord be fro home,

135 Lat not thy meneye idell gone

And loke thou wele who do hys dede,

Quyte hym therafter to his mede;

And thei that wylle bot lytell do,

Therafter thou quite is mede also.

140 A grete dede if thou have to done,

At the tone ende thou be ryght sone;

And if that thou fynd any fawte,

Amend it sone, and tarrye note.

Mych thynge behoven them

145 That gode housold schall kepyn.

Amend thy hous or thou have nede,

For better after thou schall spede;

And if that thy nede be grete,

And in the country courne be stryte,

150 Make an houswyfe on thyselve,

Thy bred thou bake for houswyfys helthe.

Amonge thi servantes if thou stondyne,

Thy werke it schall be soner done

To helpe them sone thou sterte,

155 For many handes make lyght werke.

Bysyde thee if thy neghbores thryve,

Therfore thou make no stryfe,

Bot thanke God of all thi gode

That He send thee to thy fode;

160 And than thow schall lyve gode lyfe,

And so to be a gode houswyfe.

At es he lyves that awes no dette,

Yt is no les, withouten lette.

Syte not to longe uppe at evene,

165 For drede with ale thou be oversene

Loke thou go to bede bytyme;

Erly to ryse is fysyke fyne (2).

And so thou schall be, my dere chyld,

Be welle dysposed, both meke and myld,

170 For all ther es may thei not have,

That wyll thryve, and ther gode save,

And if it thus thee betyde,

That frendes falle thee fro on every syde,

And God fro thee thi chyld take,

175 Thy wreke one God do thou not take,

For thyselve it wyll undo,

And all thes that thee longe to

Many one for ther awne foly

Spyllys themselve unthryftyly.

180 Loke, doughter, nothing thou lese,

Ne thi housbond thou not desples.

And if thou have a doughter of age,

Pute here sone to maryage;

For meydens, thei be lonely

185 And nothing syker therby.

Borow thou not, if that thou meye,

For drede thi neybour wyll sey naye;

Ne take thou nought to fyrste,

Bot thou be inne more bryste.

190 Make thee not ryche of other mens thyng,

The bolder to spend be one ferthyng.

Borowyd thinge muste nedes go home,

Yf that thou wyll to heven gone.

When the servantes have do ther werke,

195 To pay ther hyre loke thou be smerte,

Whether thei byde or thei do wende

Thus schall thou kepe them ever thi frende,

And thus thi frendes wyll be glade

That thou dispos thee wyslye and sade.

200 Now I have taught thee, my dere doughter,

The same techynge I hade of my modour:

Thinke theron both nyght and dey,

Forgette them not if that thou may,

For a chyld unborne wer better

205 Than be untaught, thus seys the letter.

Therfor Allmyghty God inne trone,

Spede us all, bothe even and morne;

And bringe us to Thy hyghe blysse,

That never more fro us schall mysse!"

1. Food

2. Good for you

0 notes

Text

Confessio Amantis, The Tale of Florent - John Gower

The “Tale of Florent” from John Gower’s Confessio Amantis is very similar to the Geoffrey Chaucer’s “Wife of Bath’s Tale”, in fact it is a retelling of it. John Gower’s Confessio Amantis is particularly fascinating collection of poems, and many of the pieces are inspired/ take directly from many older pieces. Confessio uses these re-working of pieces as a means of harkening to a virtue that was laid out in a previous text, and the virtue being represented in the “Tale of Florent” is pride.

The “Tale of Florent” follows a man named Florent who is tasked with answering the question what do women want most? If he answers incorrectly, he loses his life. Florent finds the answer in a wholly grotesque woman, who tells Florent that if her answer to his question proves to be correct, then he must marry her. Florent agrees, and the woman basically tells him that the thing women most desire is to be seen as equal to men, to be sovereign.

Florent gives this answer, is proven to be correct, and then weds the hag-like woman. The woman has another trick up her sleeve, however, as she reveals to her new husband she is young and fair. She tells Florent that he can either have her pretty during the day and ugly at night, or ugly during the day or fair by night. Our hero concedes that his wife should choose because no matter which she makes, he knows it will be the right one. Having proven sovereignty with his mate, his wife rewards Florent by being beautiful all the time.

This piece proves to be relatively progressive in that it preaches the equality of men and women, and is actually concerned with what women want.

Ther was whilom be daies olde

A worthi knyht, and as men tolde

He was Nevoeu to th'emperour

1410 And of his Court a Courteour:

Wifles he was, Florent he hihte,

He was a man that mochel myhte,

Of armes he was desirous,

Chivalerous and amorous,

1415 And for the fame of worldes speche,

Strange aventures forto seche,

He rod the Marches al aboute.

And fell a time, as he was oute,

Fortune, which may every thred

1420 Tobreke and knette of mannes sped,

Schop, as this knyht rod in a pas,

That he be strengthe take was,

And to a Castell thei him ladde,

Wher that he fewe frendes hadde:

1425 For so it fell that ilke stounde

That he hath with a dedly wounde

Feihtende his oghne hondes slain

Branchus (1), which to the Capitain

Was Sone and Heir, wherof ben wrothe

1430 The fader and the moder bothe.

That knyht Branchus was of his hond

The worthieste of al his lond,

And fain thei wolden do vengance

Upon Florent, bot remembrance

1435 That thei toke of his worthinesse

Of knyhthod and of gentilesse,

And how he stod of cousinage

To th'emperour, made hem assuage,

And dorsten noght slen him for fere:

1440 In gret desputeisoun thei were

Among hemself, what was the beste.

Ther was a lady, the slyheste

Of alle that men knewe tho,

1445 So old sche myhte unethes go,

And was grantdame unto the dede:

And sche with that began to rede,

And seide how sche wol bringe him inne,

That sche schal him to dethe winne

1450 Al only of his oghne grant,

Thurgh strengthe of verray covenant

Withoute blame of eny wiht.

Anon sche sende for this kniht,

And of hire Sone sche alleide

1455 The deth, and thus to him sche seide:

"Florent, how so thou be to wyte

Of Branchus deth, men schal respite

As now to take vengement,

Be so thou stonde in juggement

1460 Upon certein condicioun,

That thou unto a questioun

Which I schal axe schalt ansuere;

And over this thou schalt ek swere,

That if thou of the sothe faile,

1465 Ther schal non other thing availe,

That thou ne schalt thi deth receive.

And for men schal thee noght deceive,

That thou therof myht ben avised,

Thou schalt have day and tyme assised

1470 And leve saufly forto wende,

Be so that at thi daies ende

Thou come ayein with thin avys.

This knyht, which worthi was and wys,

This lady preith that he may wite,

1475 And have it under Seales write,

What questioun it scholde be

For which he schal in that degree

Stonde of his lif in jeupartie.

With that sche feigneth compaignie,

1480 And seith: "Florent, on love it hongeth

Al that to myn axinge longeth:

What alle wommen most desire

This wole I axe, and in th'empire

Wher as thou hast most knowlechinge

1485 Tak conseil upon this axinge."

Florent this thing hath undertake,

The day was set, the time take,

Under his seal he wrot his oth,

In such a wise and forth he goth

1490 Hom to his Emes court ayein;

To whom his aventure plein

He tolde, of that him is befalle.

And upon that thei weren alle

The wiseste of the lond asent,

1495 Bot natheles of on assent

Thei myhte noght acorde plat,

On seide this, an othre that.

After the disposicioun

Of naturel complexioun

1500 To som womman it is plesance,

That to an other is grevance;

Bot such a thing in special,

Which to hem alle in general

Is most plesant, and most desired

1505 Above alle othre and most conspired,

Such o thing conne thei noght finde

Be Constellacion ne kinde:

And thus Florent withoute cure

Mot stonde upon his aventure,

1510 And is al schape unto the lere,

As in defalte of his answere.

This knyht hath levere forto dye

Than breke his trowthe and forto lye

In place ther as he was swore,

1515 And schapth him gon ayein therfore.

Whan time cam he tok his leve,

That lengere wolde he noght beleve,

And preith his Em he be noght wroth,

For that is a point of his oth,

1520 He seith, that noman schal him wreke,

Thogh afterward men hiere speke

That he par aventure deie.

And thus he wente forth his weie

Alone as knyht aventurous,

1525 And in his thoght was curious

To wite what was best to do:

And as he rod al one so,

And cam nyh ther he wolde be,

In a forest under a tre

1530 He syh wher sat a creature,

A lothly wommannysch figure,

That forto speke of fleisch and bon

So foul yit syh he nevere non.

This knyht behield hir redely,

1535 And as he wolde have passed by,

Sche cleped him and bad abide;

And he his horse heved aside

Tho torneth, and to hire he rod,

And there he hoveth and abod,

1540 To wite what sche wolde mene.

And sche began him to bemene,

And seide: "Florent be thi name,

Thou hast on honde such a game,

That bot thou be the betre avised,

1545 Thi deth is schapen and devised,

That al the world ne mai the save,

Bot if that thou my conseil have."

Florent, whan he this tale herde,

Unto this olde wyht answerde

1550 And of hir conseil he hir preide.

And sche ayein to him thus seide:

"Florent, if I for the so schape,

That thou thurgh me thi deth ascape

And take worschipe of thi dede,

1555 What schal I have to my mede?"

"What thing," quod he, "that thou wolt axe."

"I bidde nevere a betre taxe,"

Quod sche, "bot ferst, er thou be sped,

Thou schalt me leve such a wedd,

1560 That I wol have thi trowthe in honde

That thou schalt be myn housebonde."

"Nay," seith Florent, "that may noght be."

"Ryd thanne forth thi wey," quod sche,

"And if thou go withoute red,

1565 Thou schalt be sekerliche ded."

Florent behihte hire good ynowh

Of lond, of rente, of park, of plowh,

Bot al that compteth sche at noght.

Tho fell this knyht in mochel thoght,

1570 Now goth he forth, now comth ayein,

He wot noght what is best to sein,

And thoghte, as he rod to and fro,

That chese he mot on of the tuo,

Or forto take hire to his wif

1575 Or elles forto lese his lif.

And thanne he caste his avantage,

That sche was of so gret an age,

That sche mai live bot a while,

And thoghte put hire in an Ile,

1580 Wher that noman hire scholde knowe,

Til sche with deth were overthrowe.

And thus this yonge lusti knyht

Unto this olde lothly wiht

Tho seide: "If that non other chance

1585 Mai make my deliverance,

Bot only thilke same speche

Which, as thou seist, thou schalt me teche,

Have hier myn hond, I schal thee wedde."

And thus his trowthe he leith to wedde.

1590 With that sche frounceth up the browe:

"This covenant I wol allowe,"

Sche seith: "if eny other thing

Bot that thou hast of my techyng

Fro deth thi body mai respite,

1595 I woll thee of thi trowthe acquite,

And elles be non other weie.

Now herkne me what I schal seie.

"Whan thou art come into the place,

Wher now thei maken gret manace

1600 And upon thi comynge abyde,

Thei wole anon the same tide

Oppose thee of thin answere.

I wot thou wolt nothing forbere

Of that thou wenest be thi beste,

1605 And if thou myht so finde reste,

Wel is, for thanne is ther nomore.

And elles this schal be my lore,

That thou schalt seie, upon this Molde

That alle wommen lievest wolde

1610 Be soverein of mannes love:

For what womman is so above,

Sche hath, as who seith, al hire wille;

And elles may sche noght fulfille

What thing hir were lievest have.

1615 "With this answere thou schalt save

Thiself, and other wise noght.

And whan thou hast thin ende wroght,

Com hier ayein, thou schalt me finde,

And let nothing out of thi minde."

1620 He goth him forth with hevy chiere,

As he that not in what manere

He mai this worldes joie atteigne:

For if he deie, he hath a peine,

And if he live, he mot him binde

1625 To such on which of alle kinde

Of wommen is th'unsemlieste:

Thus wot he noght what is the beste:

Bot be him lief or be him loth,

Unto the Castell forth he goth

1630 His full answere forto yive,

Or forto deie or forto live.

Forth with his conseil cam the lord,

The thinges stoden of record,

He sende up for the lady sone,

1635 And forth sche cam, that olde Mone.

In presence of the remenant

The strengthe of al the covenant

Tho was reherced openly,

And to Florent sche bad forthi

1640 That he schal tellen his avis,

As he that woot what is the pris.

Florent seith al that evere he couthe,

Bot such word cam ther non to mowthe,

That he for yifte or for beheste

1645 Mihte eny wise his deth areste.

And thus he tarieth longe and late,

Til that this lady bad algate

That he schal for the dom final

Yive his answere in special

1650 Of that sche hadde him ferst opposed:

And thanne he hath trewly supposed

That he him may of nothing yelpe,

Bot if so be tho wordes helpe,

Whiche as the womman hath him tawht;

1655 Wherof he hath an hope cawht

That he schal ben excused so,

And tolde out plein his wille tho.

And whan that this Matrone herde

The manere how this knyht ansuerde,

1660 Sche seide: "Ha treson, wo thee be,

That hast thus told the privite,

Which alle wommen most desire!

I wolde that thou were afire."

Bot natheles in such a plit

1665Florent of his answere is quit:

And tho began his sorwe newe,

For he mot gon, or ben untrewe,

To hire which his trowthe hadde.

Bot he, which alle schame dradde,

1670 Goth forth in stede of his penance,

And takth the fortune of his chance,

As he that was with trowthe affaited.

This olde wyht him hath awaited

In place wher as he hire lefte:

1675 Florent his wofull heved uplefte

And syh this vecke wher sche sat,

Which was the lothlieste what

That evere man caste on his yhe:

Hire Nase bass, hire browes hyhe,

1680 Hire yhen smale and depe set,

Hire chekes ben with teres wet,

And rivelen as an emty skyn

Hangende doun unto the chin,

Hire Lippes schrunken ben for age,

1685 Ther was no grace in the visage,

Hir front was nargh, hir lockes hore,

Sche loketh forth as doth a More,

Hire Necke is schort, hir schuldres courbe,

That myhte a mannes lust destourbe,

1690 Hire body gret and nothing smal,

And schortly to descrive hire al,

Sche hath no lith withoute a lak;

Bot lich unto the wollesak

Sche proferth hire unto this knyht,

1695 And bad him, as he hath behyht (2),

So as sche hath ben his warant,

That he hire holde covenant,

And be the bridel sche him seseth.

Bot godd wot how that sche him pleseth

1700 Of suche wordes as sche spekth:

Him thenkth welnyh his herte brekth

For sorwe that he may noght fle,

Bot if he wolde untrewe be.

Loke, how a sek man for his hele

1705 Takth baldemoine with Canele,

And with the Mirre takth the Sucre,

Ryht upon such a maner lucre

Stant Florent, as in this diete:

He drinkth the bitre with the swete,

1710 He medleth sorwe with likynge,

And liveth, as who seith, deyinge;

His youthe schal be cast aweie

Upon such on which as the weie

Is old and lothly overal.

1715 Bot nede he mot that nede schal:

He wolde algate his trowthe holde,

As every knyht therto is holde,

What happ so evere him is befalle:

Thogh sche be the fouleste of alle,

1720 Yet to th'onour of wommanhiede

Him thoghte he scholde taken hiede;

So that for pure gentilesse,

As he hire couthe best adresce,

In ragges, as sche was totore,

1725 He set hire on his hors tofore

And forth he takth his weie softe;

No wonder thogh he siketh ofte.

Bot as an oule fleth be nyhte

Out of alle othre briddes syhte,

1730 Riht so this knyht on daies brode

In clos him hield, and schop his rode

On nyhtes time, til the tyde

That he cam there he wolde abide;

And prively withoute noise

1735 He bringth this foule grete Coise

To his Castell in such a wise

That noman myhte hire schappe avise,

Til sche into the chambre cam:

Wher he his prive conseil nam

1740 Of suche men as he most troste,

And tolde hem that he nedes moste

This beste wedde to his wif,

For elles hadde he lost his lif.

The prive wommen were asent,

1745 That scholden ben of his assent:

Hire ragges thei anon of drawe,

And, as it was that time lawe,

She hadde bath, sche hadde reste,

And was arraied to the beste.

1750 Bot with no craft of combes brode

Thei myhte hire hore lockes schode,

And sche ne wolde noght be schore

For no conseil, and thei therfore,

With such atyr as tho was used,

1755 Ordeinen that it was excused,

And hid so crafteliche aboute,

That noman myhte sen hem oute.

Bot when sche was fulliche arraied

And hire atyr was al assaied,

1760 Tho was sche foulere on to se:

Bot yit it may non other be,

Thei were wedded in the nyht;

So wo begon was nevere knyht

As he was thanne of mariage.

1765 And sche began to pleie and rage,

As who seith, I am wel ynowh;

Bot he therof nothing ne lowh,

For sche tok thanne chiere on honde

And clepeth him hire housebonde,

1770 And seith, "My lord, go we to bedde,

For I to that entente wedde,

That thou schalt be my worldes blisse:"

And profreth him with that to kisse,

As sche a lusti Lady were.

1775 His body myhte wel be there,

Bot as of thoght and of memoire

His herte was in purgatoire.

Bot yit for strengthe of matrimoine

He myhte make non essoine,

1780 That he ne mot algates plie

To gon to bedde of compaignie:

And whan thei were abedde naked,

Withoute slep he was awaked;

He torneth on that other side,

1785 For that he wolde hise yhen hyde

Fro lokynge on that foule wyht.

The chambre was al full of lyht,

The courtins were of cendal thinne

This newe bryd which lay withinne,

1790 Thogh it be noght with his acord,

In armes sche beclipte hire lord,

And preide, as he was torned fro,

He wolde him torne ayeinward tho;

"For now," sche seith, "we ben bothe on."

1795 And he lay stille as eny ston,

Bot evere in on sche spak and preide,

And bad him thenke on that he seide,

Whan that he tok hire be the hond.

He herde and understod the bond,

1800 How he was set to his penance,

And as it were a man in trance

He torneth him al sodeinly,

And syh a lady lay him by

Of eyhtetiene wynter age,

1805 Which was the faireste of visage

That evere in al this world he syh:

And as he wolde have take hire nyh,

Sche put hire hand and be his leve

Besoghte him that he wolde leve,

1810 And seith that forto wynne or lese

He mot on of tuo thinges chese,

Wher he wol have hire such on nyht,

Or elles upon daies lyht,

For he schal noght have bothe tuo.

1815 And he began to sorwe tho,

In many a wise and caste his thoght,

Bot for al that yit cowthe he noght

Devise himself which was the beste.

And sche, that wolde his hertes reste,

1820 Preith that he scholde chese algate,

Til ate laste longe and late

He seide: "O ye, my lyves hele,

Sey what you list in my querele,

I not what ansuere I schal yive:

1825 Bot evere whil that I may live,

I wol that ye be my maistresse,

For I can noght miselve gesse

Which is the beste unto my chois.

Thus grante I yow myn hole vois,

1830 Ches for ous bothen, I you preie;

And what as evere that ye seie,

Riht as ye wole so wol I."

"Mi lord," sche seide," grant merci,

For of this word that ye now sein,

1835 That ye have mad me soverein,

Mi destine is overpassed,

That nevere hierafter schal be lassed

Mi beaute, which that I now have,

Til I be take into my grave;

1840 Bot nyht and day as I am now

I schal alwey be such to yow.

"The kinges dowhter of Cizile

I am, and fell bot siththe awhile,

As I was with my fader late,

1845 That my Stepmoder for an hate,

Which toward me sche hath begonne,

Forschop me, til I hadde wonne

The love and sovereinete

Of what knyht that in his degre

1850 Alle othre passeth of good name:

And, as men sein, ye ben the same,

The dede proeveth it is so;

Thus am I youres evermo."

Tho was plesance and joye ynowh,

1855 Echon with other pleide and lowh;

Thei live longe and wel thei ferde,

And clerkes that this chance herde

Thei writen it in evidence,

To teche how that obedience

1860 Mai wel fortune a man to love

And sette him in his lust above,

As it befell unto this knyht.

Forthi, my Sone, if thou do ryht,

Thou schalt unto thi love obeie,

1865 And folwe hir will be alle weie.

Min holy fader, so I wile:

For ye have told me such a skile

Of this ensample now tofore,

That I schal evermo therfore

1870 Hierafterward myn observance

To love and to his obeissance

The betre kepe: and over this

Of pride if ther oght elles is,

Wherof that I me schryve schal,

1875 What thing it is in special,

Mi fader, axeth, I you preie.

Now lest, my Sone, and I schal seie:

For yit ther is Surquiderie,

Which stant with Pride of compaignie;

1880 Wherof that thou schalt hiere anon,

To knowe if thou have gult or non

Upon the forme as thou schalt hiere:

Now understond wel the matiere.

1. Branchus is the family of the knight Florent kills, which sparks the whole journey as Grandma Branchus is the one who tasks Florent with procuring an answer to her fateful question: what do women desire the most?

2. Promised

0 notes

Text

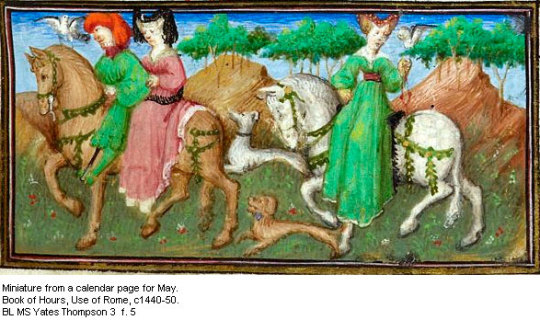

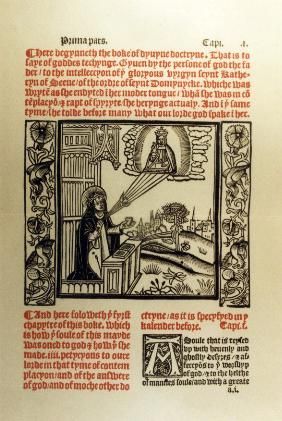

Images

This crude illustration fits well with Marie De France’s Yonec, with the caption “love is a rebellious bird.“ -Emily

Gawain cuts off the Green Knights head, thus initiating the pact and setting the path of the story. -Emily

This illustration is from a Medieval Book of hours. These books could contain a number of items from calendars, prayers, or lives of saints. -Callie

A detail from an illuminated manuscript. Manuscripts were hand written and featured decorative images in letters and margins. -Callie

These are all the legendary women from Chaucer’s “Legend of Good Women.” -Adam

A medieval painting of the virgin Mother Mary, the pure protagonist of the lyric “I Sing of a Maiden.” -Adam