Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Conflict between Digital Citizenship and Social Media: Authority, Abuse, and Governance

The Function of Disagreement in Online Communities

Social media is frequently portrayed as a forum for candid conversation and community development. Nonetheless, power struggles among people, organisations, and platforms influence interactions that take place online. Competition for attention, identity-based discrimination, and political disagreements can all lead to conflict in digital spaces. Therefore, when claiming their presence online, marginalised communities frequently experience harassment or exclusion (Heath, 2018).

Who controls online speech is one of the main problems. Social media companies enforce content moderation policies that may disproportionately silence some voices, even as they support free expression. There are continuous discussions concerning free speech versus platform responsibility as a result of governments and regulatory agencies influencing what content is acceptable (Marwick & Caplan, 2018).

Who Establishes the Guidelines for Social Media Governance?

Government rules, community-driven guidelines, and corporate policies all influence governance in digital spaces. Commercial interests drive social media platforms' efforts to strike a balance between user engagement and financial gain while upholding safety regulations. Although legal frameworks are introduced by governments to control online content, enforcement differs from nation to nation. Furthermore, community moderators create micro-level governance structures by establishing rules within particular groups.

The platform's accountability is still lacking in spite of these governance models. Many businesses do not adequately handle online abuse, which exposes users to algorithmic bias, misinformation, and harassment. Digital citizenship will continue to revolve around debates about platform ethics, content regulation, and governance as social media develops (Marwick & Caplan, 2018).

Digital Abuse and Online Harassment

A recurring problem in digital spaces, harassment can take many different forms, such as online hate speech, doxxing, and cyberstalking. Research indicates that women, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and members of racial minorities are disproportionately affected by online abuse. According to Haslop et al. (2021), women and transgender people are frequently the targets of online abuse, and 59% of girls worldwide have experienced online harassment, according to a 2020 Plan International report.

Although online harassment is frequently written off as "just words," the consequences can be dire. Due to recurrent abuse, victims report feeling depressed, anxious, and self-conscious. The issue is made worse by the fact that offenders can evade punishment due to the anonymity of social media. According to The Guardian (2016), combating online harassment necessitates more extensive cultural and structural adjustments because it frequently reflects offline discrimination.

Solutions: Community-Based, Legal, and Accountability on the Platform

Legal Methods

Legal actions are being taken by governments all over the world to stop online harassment. The Online Safety Act 2021 in Australia requires platforms to take down dangerous content within 24 hours. Cyber threats and abuse are covered by other laws, such as the Criminal Code Act of 1995. Enforcement is still difficult, though, especially when it comes to transnational crimes and covert forms of harassment that defy legal definitions.

Digital Activism and Community Opposition

A key component of the fight against online abuse is activism. While artists and comedians like Hannah Gadsby use humour to critique misogyny in online spaces, movements like #MeToo have brought attention to gender-based harassment (Vitis & Gilmour, 2017). However, some contend that humour may not always be a successful tool for resistance and runs the risk of trivialising important issues (Sundén & Paasonen, 2019).

Accountability of the Platform

There is growing pressure on social media companies to improve AI-based detection systems, moderate harmful content, and improve reporting procedures. According to a Pew study from 2021, 79% of users think social media companies are not doing enough to combat online abuse. Platforms have responded by implementing community guidelines and content moderation AI, but these steps frequently fall short of stopping systemic discrimination and algorithmic biases.

References:

Haslop, C., O’Rourke, F., & Southern, R. (2021). #NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide, in a UK student online culture. Convergence, 27(5), 1418–1438.

Heath, M. K. (2018). What kind of (digital) citizen? A between-studies analysis of research and teaching for democracy. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 35(5), 342-356.

Marwick, A. E., & Caplan, R. (2018). Drinking male tears: Language, the manosphere, and networked harassment. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 543-559.

Plan International. (2020). Free to be online? Plan International Report on Girls’ Experiences of Online Harassment.

Sundén, J., & Paasonen, S. (2019). Inappropriate laughter: Affective homophily and the unlikely comedy of #MeToo. Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119883425

The Guardian. (2016). The dark side of Guardian comments. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/12/the-dark-side-of-guardian-comments

Vitis, L., & Gilmour, F. (2017). Dick pics on blast: A woman’s resistance to online sexual harassment using humour, art and Instagram. Crime, Media, Culture, 13(3), 335-355.

#DigitalCitizenship#OnlineHarassment#SocialMediaGovernance#Cyberbullying#digital_community#mda20009#week10

0 notes

Text

Gaming Communities' Development: Esports, Live Streaming, and Social Gaming

The Development of Online Communities and Gaming

Arcade culture in the 1970s and 1980s, where players congregated to compete and mingle, is where gaming's history begins. With local multiplayer video games like Street Fighter II and couch co-op on the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), this social element persisted into the 1990s. In games like World of Warcraft and Counter-Strike, players can now connect globally thanks to the introduction of online multiplayer in the 2000s (Newman, 2017).

As a result of this change, gaming evolved into a virtual community where users could create online friendships, guilds, and clans. These days, gaming encompasses more than just playing; it also involves observing, engaging, and taking part in a wider network of shared experiences (Jenkins, 2006).

The Effects of Gaming Platforms on Society

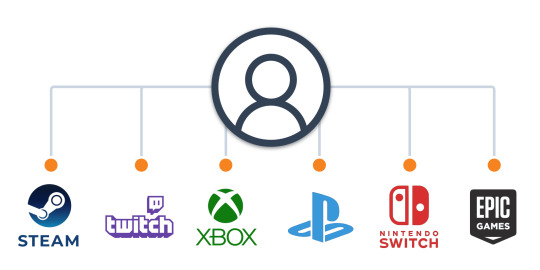

Three main platforms influence the gaming landscape:

Consoles (PlayStation, Xbox, Nintendo Switch): Designed with social multiplayer and exclusive content in mind.

PC gaming (Steam, Epic Games Store): Provides powerful gaming with modding features that let users change the graphics and gameplay.

Focused on accessible, informal experiences, mobile gaming (Google Play, App Store) frequently uses social networks to engage users (Juul, 2010).

The distinctions between these categories have become even more hazy with the rise of cross-platform play, which allows users to switch between devices and preserve social ties across various ecosystems (Taylor, 2018).

Social and Competitive Gaming's Ascent

Games that incorporate social interactions into gameplay are referred to as social gaming. Among the examples are:

FarmVille: Encourages users to interact with friends while managing virtual farms.

Candy Crush: Encourages friendly competition among players through leaderboards and challenges (Järvinen, 2011).

Esports, or competitive gaming, has grown into a worldwide industry beyond casual gaming, with notable competitions like:

Every year, millions of people watch the League of Legends World Championship.

The International in Dota 2 is renowned for having prize pools that break records (Taylor, 2018).

With sponsorships, streaming agreements, and large audiences, esports has turned video gaming into a lucrative profession.

Streaming Games: A Novel Approach to Entertainment

The way that people view and interact with gaming content has been completely transformed by game streaming services. Well-liked services consist of:

The biggest live-streaming website is Twitch, where content producers create communities centred around video games.

YouTube Gaming: Combines live streaming and pre-recorded gaming videos.

According to Hamilton, Garretson, and Kerne (2014), Facebook Gaming incorporates streaming with pre-existing social networks.

As gaming celebrities, streamers like Ninja and Pokimane make money from sponsorships, donations, and subscriptions. Gaming has become a participatory culture as a result of streaming, which has dissolved the distinction between players and viewers (Jenkins, 2006).

Gaming Knowledge Communities and Modding

The culture of gaming heavily relies on knowledge communities. These player-controlled areas provide:

Wikis for video games, like the Stardew Valley Wiki, are crowdsourced knowledge-sharing sites.

Reddit forums and Steam discussions are places where players talk about updates, tactics, and technical problems.

The lifespan of a game can be extended by players creating modifications (mods) that improve or change gameplay (Sotamaa, 2010).

Dota 2 (a Warcraft III mod) and Counter-Strike (a Half-Life mod) are two of the most well-known games ever made thanks to modding. These player-driven inventions show how the industry is being actively shaped by gaming communities.

The Prospects for Gaming Communities

With the advent of new technologies and social trends, gaming is expected to grow in the future. These include:

Cloud gaming, such as Xbox Cloud Gaming and Google Stadia, eliminates the need for pricey hardware.

VR & AR Gaming: Combining digital and real-world environments (Meta Quest, Pokémon Go).

Improving world-building and narrative in video games through AI-generated content (Weststar, 2015).

Gaming's influence on society and culture will only increase as it develops further, changing online interaction, competition, and entertainment.

References

Hamilton, W. A., Garretson, O., & Kerne, A. (2014). Streaming on Twitch: Fostering participatory communities of play. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1315–1324.

Järvinen, A. (2011). Understanding social games: Social interaction and design. Games and Culture, 6(4), 291-303.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. NYU Press.

Juul, J. (2010). A casual revolution: Reinventing video games and their players. MIT Press.

Newman, J. (2017). Playing with videogames. Routledge.

Sotamaa, O. (2010). When the game is not enough: Motivations and practices among computer game modding culture. Games and Culture, 5(3), 239-255.

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Watch me play: Twitch and the rise of game live streaming. Princeton University Press.

Weststar, J. (2015). Understanding video game developers as an occupational community. Information, Communication & Society, 18(10), 1238-1252.

Anderton, K. (2018, June 25). The Impact Of Gaming: A Benefit To Society

[Infographic]. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinanderton/2018/06/25/the-impact-of-gaming-a-benefit-to-society-infographic/

0 notes

Text

The Development of Augmented Reality Filters and How They Affect Online Communities

What is Augmented Reality?

Overlaying digital objects on top of real-world surroundings is known as augmented reality, or AR. AR filters, made popular by apps like Instagram and Snapchat, alter facial features, apply effects, and produce completely new digital identities (Azuma, 1997).

From straightforward enhancements like dog ears or flower crowns, AR filters have evolved into sophisticated beauty filters that alter bone structure, smooth skin, and reshape facial features. Questions concerning digital identity and self-perception are brought up by these hyper-realistic changes.

AR Filters' Popularity on Social Media

AR filters have become more popular as a result of social media platforms, especially Instagram and Snapchat. Among the important figures are:

Of Instagram users, 46% have experimented with the filter effect.

Every day, 500 million people use Instagram Stories, and many of them use AR filters.

Every month, 700 million users interact with AR effects on various Meta platforms.

Filters are now instruments for identity experimentation and self-improvement rather than just amusement. Some criticise AR for reinforcing uniform beauty standards, while others contend that it fosters creativity (Miller & McIntyre, 2022).

Beauty filters and unrealistic ideals of beauty

Designed to "enhance" facial features by smoothing skin, enlarging lips, and reshaping noses, beauty filters are among the most widely used AR tools. A globalised, unattainable standard of beauty is a result of these changes, which frequently mirror Western beauty standards (Rettberg, 2014).

Exposure to beauty-enhancing filters on a regular basis can cause people to view their bodies as objects for evaluation, according to the Objectification Theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Following extended use of filters, many users express dissatisfaction with their natural appearance, which can result in problems with self-esteem and heightened interest in cosmetic surgery (Rajanala, Maymone & Vashi, 2018).

Snapchat Dysmorphia and the Discussion of Mental Health

Snapchat dysmorphia, the practice of people seeking cosmetic surgery to look like their filtered selves, is becoming a bigger problem. Patients now show filtered selfies to plastic surgeons as reference images rather than celebrity photos (Burnell, Kurup & Underwood, 2021).

This phenomenon demonstrates a vicious cycle of body dissatisfaction and AR filter use:

According to Perloff (2014), users who use beauty filters internalise unrealistic expectations, feel dissatisfied with their actual appearance, and seek out additional digital or physical modifications. By flagging filtered photos, social media companies try to control extreme beauty modification, but algorithm-driven content recommendations still encourage unattainable beauty standards (Lawrence & Cambre, 2020).

The Authenticity Debate and the Digital-Forensic Gaze

A "digital-forensic gaze" has developed as AR filters make it harder to distinguish between digital enhancement and reality (Lawrence & Cambre, 2020). Users of social media now carefully examine photos for evidence of editing, frequently participating in online discussions about what is "real" and what is artificially created.

Because it promotes perfectionist standards, this forensic gaze can be problematic—even photos that appear natural are examined for indications of enhancement. Self-presentation and the creation of digital identities are influenced by the paradox created by the pressure to remain authentic while still adhering to beauty standards.

AR Filters' Implications for Gender

AR filters are often coded as feminine technologies, focusing on beautification and self-enhancement. Research shows that:

Women use filters to align with beauty norms, reinforcing traditional gender expectations.

Men may avoid certain filters due to masculinity concerns, though humor-based and gaming-related AR tools are more widely accepted (Pescott, 2020).

Children as young as ten understand and internalize gendered filter use, indicating that beauty standards are learned early (Pescott, 2020).

These findings suggest that filters are not just fun tools—they actively shape perceptions of gender, self-worth, and digital identity.

References:

Azuma, R. T. (1997). A survey of augmented reality. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 6(4), 355–385.

Burnell, K., Kurup, A. R., & Underwood, M. K. (2021). Snapchat lenses and body image concerns. Body Image, 38, 12–19.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206.

Lawrence, S., & Cambre, C. (2020). “Do I look like my selfie?”: Filters and the digital-forensic gaze. Social Media + Society, 6(1), 1–13.

Miller, L., & McIntyre, M. (2022). From surgery to cyborgs: A thematic analysis of popular media commentary on Instagram filters. New Media & Society, 24(1), 123–140.

Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles, 71(11–12), 363–377.

Pescott, C. (2020). Children and digital filters: Understanding gendered technology use. Journal of Digital Culture, 7(2), 89–104.

Rajanala, S., Maymone, M. B. C., & Vashi, N. A. (2018). Selfies—living in the era of filtered photographs. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, 20(6), 443–444.

Rettberg, J. W. (2014). Seeing ourselves through technology: How we use selfies, blogs and wearable devices to see and shape ourselves. Palgrave Macmillan.

Peng, H. (2020). AI-powered beauty filters in digital banking: The case of AliPay. Journal of Digital Finance, 5(3), 215–229.

#AugmentedReality#DigitalIdentity#SocialMediaFilters#BeautyStandards#SnapchatDysmorphia#DigitalCitizenship#digital_community#mda20009#week8

0 notes

Text

The Effects of Social Media on Body Image, Aesthetic Labour, and Digital Citizenship

Social Media Beauty Standards and Aesthetic Templates

Social media is dominated by standardised beauty trends, which are referred to as aesthetic templates (Duffy, 2017). These include particular photo filters, body modifications, and makeup looks, which contribute to the rise of unrealistic body ideals.

A popular beauty standard on Instagram is the idea of "Instagram Face," which is defined by full lips, sculpted cheekbones, and poreless, smooth skin (Carrotte et al., 2017). This template promotes excessive photo editing and cosmetic enhancements, which feeds into self-doubt and social comparison.

Appearance is a type of social currency in the visual culture that social media promotes. Influencers curate extremely polished images to keep followers interested, which can lead to negative self-perceptions and a distorted self-image, especially in younger audiences (Bishop, 2021).

Are Public Health Campaigns Beneficial or Dangerous?

Although social media is an effective tool for raising public awareness of health issues, it can also reinforce negative standards of beauty.

Some initiatives, like Movember, successfully advance men's health by enticing people to take part in awareness-raising events. Nonetheless, extreme dieting, impractical fitness objectives, and unachievable body ideals are encouraged by some fitness and wellness trends, and these behaviours have been connected to eating disorders and body dysmorphia (Daniels, 2016).

The emergence of thinspiration and fitspiration content shows how social media can perpetuate unhealthy ideals of beauty. Although platforms have made an effort to control these trends, users are still exposed to harmful content through algorithm-driven content recommendations (Duffy & Meisner, 2022).

The Cost of Internet Stardom: Aesthetic Labour & Microcelebrity

According to Senft (2012), the microcelebrity phenomenon is when people position themselves as influencers in an effort to attract followers and achieve financial success. However, aesthetic labor—the ongoing effort to preserve a skilfully constructed image—is necessary to maintain this status.

This work can be seen in a number of influencer categories:

To keep up a perfect online persona, beauty influencers use cosmetic enhancements, makeup, and filters.

Influencers in the fitness industry frequently portray an idealised view of health and body image that may not be true to their actual situation.

Influencers in the fashion industry advocate carefully chosen looks that demand hefty sums of money.

According to Dean (2005), the persistent pressure to appear flawless has detrimental effects on mental health, including low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression.

The pornification of online content

The growing sexualisation of self-presentation on digital platforms is referred to as pornification (Drenten et al., 2019). The way that men and women portray themselves online is one area where this trend is especially noticeable.

While men are urged to emphasise muscularity and dominance, women are frequently subjected to aesthetic pressures that centre on hyper-feminine beauty standards, such as exaggerated curves. Social media algorithms reinforce the emphasis on physical attractiveness by giving more visibility to highly sexualised or visually appealing content (Marshall, 2010).

This raises moral questions about the normalisation of unattainable beauty standards and self-objectification, especially for younger audiences who are more susceptible to influence.

Mental Health and the Crisis of Body Image

Increased body dissatisfaction has been closely associated with social media, with studies pointing to important risks including:

A rise in social comparison-related body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) (Dorfman et al., 2018).

Elevated anxiety and depression, particularly among regular image-based platform users (Duffy, 2017).

Younger people seeking to meet the ideal of beauty on social media are increasingly undergoing cosmetic surgery.

A few platforms have tried to implement policies to mitigate these impacts. For instance, Instagram has tried eliminating likes, and TikTok has prohibited specific weight-loss campaigns. The promotion of carefully chosen beauty content by engagement-driven algorithms, however, limits these efforts.

Ways to Make the Digital Environment Healthier

There are various actions that people and platforms can take to lessen the detrimental effects of social media on mental health and body image:

Recognise unattainable beauty standards by realising that the majority of photos on social media are heavily Photoshopped.

Instruct users in media literacy so they can evaluate influencer endorsements and beauty trends critically.

Encourage self-acceptance and a variety of body types by supporting body-positive influencers.

Control influencer content to guarantee ethical marketing and promotion strategies.

By highlighting the fact that beauty is varied and not solely determined by social media trends, you can promote self-acceptance.

References:

Bishop, S. (2021). Influencer management tools: Algorithmic cultures, brand safety, and bias. Social Media + Society, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211003066

Carrotte, E. R., Prichard, I., & Lim, M. S. C. (2017). ‘Fitspiration’ on social media: A content analysis of gendered images. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(3).

Daniels, E. A. (2016). Sexiness on social media: The social costs of using a sexy profile photo. Sexualization, Media, & Society, 2(4), 1–10.

Dean, D. (2005). Recruiting a self: Women performers and aesthetic labour. Work, Employment & Society, 19(4), 761–774.

Dorfman, R. G., Vaca, E. E., Mahmood, E., Fine, N. A., & Schierle, C. (2018). Plastic surgery-related hashtag utilization on Instagram: Implications for education and marketing. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 38(3), 332–338.

Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2019). Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic, and the monetization of attention. Gender, Work and Organization, 1–26.

Duffy, B. E. (2017). (Not) getting paid to do what you love: Gender, social media, and aspirational work. Yale University Press.

Duffy, B. E., & Meisner, C. (2022). Platform governance at the margins: Social media creators’ experiences with algorithmic (in)visibility. Media, Culture & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221111923

Marshall, D. (2010). The promotion and presentation of the self: Celebrity as a marker of presentational media. Celebrity Studies, 1(1), 35-48.

Senft, T. M. (2012). Microcelebrity and the branded self. In Hartley, J., Burgess, J., & Bruns, A. (Eds.), A Companion to New Media Dynamics. Blackwell, UK.

#DigitalCitizenship#BodyImage#SocialMediaActivism#InfluencerCulture#AestheticLabor#digital_community#mda20009#week7

0 notes

Text

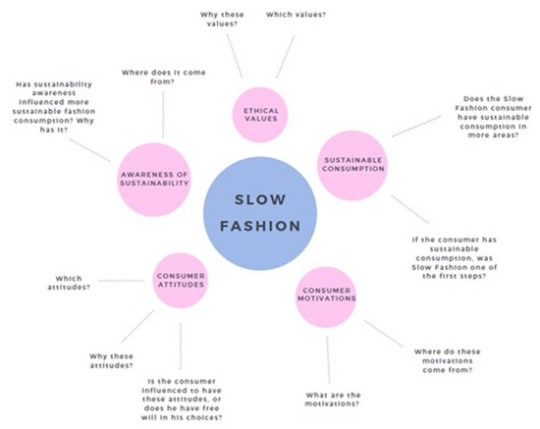

How Social Media is Changing Fashion Activism through Digital Citizenship and Slow Fashion

Digital Citizenship: More Than Just Internet Use

Effective, moral, and responsible use of online platforms is referred to as "digital citizenship" (Ribble, 2012). This entails using digital spaces critically and morally in today's hyperconnected world, which goes beyond simply browsing social media.

A responsible digital citizen takes part in activism, maintains a safer online environment, and works to stop false information. An effective illustration of digital citizenship in action is the #PayUp campaign, which surfaced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social media users started hashtag campaigns and petitions against major brands like Fashion Nova and Urban Outfitters for not paying garment workers for completed orders, which eventually forced the companies to pay their workers (Nguyen et al., 2020).

What is Slow Fashion? Why Is It Important to Us?

The antithesis of fast fashion, slow fashion promotes responsible consumption, ethical labour practices, and sustainability (Domingos et al., 2022). Using organic and recycled materials, paying workers fairly, and emphasising quality over quantity are its main goals rather than following trends and overconsumption.

Conversely, there are terrible social and environmental effects of the fast fashion industry. 10% of carbon emissions and 20% of wastewater worldwide are attributed to the fashion industry (Henninger et al., 2017). Especially in nations like Bangladesh, India, and Cambodia, millions of garment workers endure hazardous working conditions and low pay. Global waste is further increased by the fact that many brands destroy unsold clothing rather than recycling or donating it (DW Planet A, 2022).

Constant criticism has been levelled at companies like SHEIN for their environmental damage, mass overproduction, and abusive labour practices. The brand continues to thrive in spite of these worries thanks to its extremely low prices and well-liked TikTok hauls. In order to inform customers and hold companies responsible, digital activism is essential in this situation.

How Sustainable Fashion Is Promoted by Digital Activism

Social media has revolutionised fashion activism by enabling customers to have moral conversations and encourage sustainable practices from brands. The power dynamic has changed due to online movements, which have made it simpler for people to demand transparency.

Hashtag campaigns are among the most powerful instruments of digital activism. For instance, Fashion Revolution launched the #WhoMadeMyClothes movement, which calls on companies to reveal their supply chains and enhance working conditions. Via social media sites like YouTube and Instagram, ethical influencers like Venetia La Manna and Kristen Leo have exposed the practice of "greenwashing," in which companies misrepresent the sustainability of their products. Furthermore, programs like The Second Runway and Big Sister Swap have promoted circular fashion as a remedy for wasteful consumption by encouraging upcycling and secondhand shopping.

Consequently, corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become mandatory. Public outrage against brands that violate moral principles demonstrates that customers have the ability to demand change (Brewer, 2019). In order to stay competitive in a market that is becoming more and more conscious, businesses are now releasing sustainability reports and increasing supply chain transparency.

How Can YOU Change Things?

We have the ability to change the fashion industry as digital citizens by taking modest but significant steps. This is how you can help:

Support ethical influencers by following them and interacting with content that encourages sustainability and conscientious purchasing.

Do your research on brands before purchasing; look for ethical certifications and supply chain transparency.

Educate rather than attack: Instead of using online humiliation to educate someone who is ignorant of sustainability issues, share knowledge.

Encourage the use of secondhand clothing by thrifting, upcycling, and exchanging items rather than purchasing new ones.

Advocate on social media – Participate in conversations about ethical fashion, sign petitions, and share educational posts.

The fashion industry is becoming more ethical and sustainable with each post, share, and purchase. You can influence significant change in the fashion industry by practicing mindful digital citizenship!

References:

Brewer, M. K. (2019). Slow fashion in a fast fashion world: Promoting sustainability and responsibility. Laws, 8(4), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws8040024

Domingos, M., Vale, V. T., & Faria, S. (2022). Slow fashion consumer behavior: A literature review. Sustainability, 14(5), 2860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052860

Henninger, C. E., Ryding, D., Alevizou, P. J., & Goworek, H. (2017). Sustainability in fashion: A cradle to upcycle approach. Palgrave.

Nguyen, T., Chollier, L., & Moore, S. (2020). #PayUp: Digital activism in fashion’s crisis response. Journal of Fashion Marketing & Management, 24(4), 637-652.

DW Planet A. (2022). If you think fast fashion is bad, check out SHEIN. https://www.dw.com/en/if-you-think-fast-fashion-is-bad-check-out-shein/video-67045560

Ribble, M. (2012). Digital citizenship in schools: Nine elements all students should know. ISTE.

0 notes

Text

What is Digital Citizenship?

The internet has reshaped the way we participate in society—how we communicate, engage in activism, and even vote. Digital citizenship, platformization, hashtag publics, and political engagement are key areas that define this transformation. Here's a breakdown of these concepts and why they matter.

Digital Citizenship: Different Ways It Is Understood and Defined

Digital citizenship describes how we engage with technology in a responsible way within our communities. Just as traditional citizenship involves rights and duties, our online presence also requires ethical conduct, digital competence, and active involvement. Digital citizenship can be understood through several key aspects:

✔️ Online Safety – Safeguarding personal information, preventing cyberbullying, and demonstrating responsible online behavior (Ribble, 2012).

✔️ Digital Learning & Literacy – Developing skills to navigate the digital world effectively, verifying information, and using platforms ethically (Livingstone & Helsper, 2007).

✔️ Platform & Algorithmic Impact – Recognizing how social media platforms, their policies, and their underlying algorithms influence our online experiences (Gillespie, 2018).

A good digital citizen leverages technology constructively—to communicate, innovate, and contribute to online communities.

Platformization: A Central Concern for Media Research

Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram are no longer just tools for connection; they shape how we interact, share information, and engage with society. This process is called platformization—the growing centrality of social media in all aspects of life (Helmond, 2015).

📌 What is a Platform?

Computational – A base for technological innovation.

Political – A space for voices to be heard.

Architectural – Designed to facilitate digital expression (e.g., YouTube).

Key idea: Platforms control the flow of information, shaping not just our digital experiences but also public discourse.

Hashtag Publics: New Forms of Activism and Community Building

Hashtags have become a powerful tool for modern activism, enabling the organization of online discussions and the amplification of diverse voices. These hashtag-driven communities, often referred to as "hashtag publics," coalesce around shared causes and social movements.

🚀 Examples of Hashtag Activism:

📌 #BlackLivesMatter – A movement against racial injustice.

📌 #MeToo – A campaign raising awareness about sexual harassment and assault.

📌 #ClimateChange – An advocacy effort for environmental action.

Hashtags function as digital labels, facilitating rapid mobilization, widespread awareness campaigns, and the development of global solidarity. While they have provided marginalized groups with new avenues for demanding change, they also underscore the digital divide, as those lacking access to technology may find their voices excluded.

Political Engagement: How Social Media is Changing the Way We Engage with Politics

The political landscape has shifted significantly online. Traditional forms of political involvement, such as party membership, are waning, while digital participation—including online petition signing, following political figures, and engaging in policy discussions on social media—is becoming increasingly prevalent (Chadwick, 2013).

📌 The Influence of Social Media on Politics: ✔️ Platforms serve as tools for voter mobilization, fundraising efforts, and political debates (Bennett & Segerberg, 2013). ✔️ Politicians cultivate their online presence to appeal to diverse segments of the population. ✔️ Digital campaigns play a significant role in election outcomes—the 2016 Trump campaign demonstrated the power of perceived authenticity (even when controversial) over conventional, polished political strategies.

While social media has broadened access to political engagement, it also presents challenges related to the spread of misinformation, manipulation tactics, and the influence of these platforms on democratic dialogue.

References:

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2013). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Cambridge University Press.

Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford University Press.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

Helmond, A. (2015). The platformization of the web: Making web data platform ready. Social Media+ Society, 1(2), 2056305115603080.

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. J. (2007). Gradations in digital inclusion: Children, young people, and the digital divide. New Media & Society, 9(4), 671-696.

Papacharissi, Z. (2015). Affective publics: Sentiment, technology, and politics. Oxford University Press.

Ribble, M. (2012). Digital citizenship in schools: Nine elements all students should know. ISTE.

0 notes

Text

Reality TV, Social Media, and Digital Publics: More Than Just Entertainment

Reality TV offers more than just escapism; it provides a glimpse into the complexities of human interaction, competition, and societal trends. These programs walk a fine line between authentic moments and staged drama, captivating viewers with narratives that, while presented as unscripted, are often carefully crafted in the editing room. From the strategic challenges of shows like Survivor and the culinary battles of MasterChef to the fly-on-the-wall intimacy of Keeping Up with the Kardashians and the heartwarming transformations of Queer Eye, reality TV resonates with audiences by tapping into relatable experiences and fostering a sense of connection (Hill, 2005).

What Makes Reality TV So Popular?

At its core, reality TV captures real people in real situations—whether they’re competing for survival (Survivor), showcasing their talent (The Voice), or living extravagant lifestyles (Keeping Up with the Kardashians). The relatability of these shows, combined with elements of drama, competition, and personal growth, keeps audiences hooked (Kavka, 2012).

But reality TV isn't just about what happens on-screen. The rise of social media has made it more participatory than ever. Fans don’t just watch—they engage, debate, and even influence the outcomes of their favorite shows (Couldry, 2012).

Social Media and Audience Interaction

Social media platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok have revolutionized the way audiences engage with reality TV. Viewers now actively participate in the narrative by sharing memes, debating contestants' actions, and speculating about upcoming events in real time. Some shows have even incorporated social media directly into their formats: For example, Love Island empowers viewers to vote for their preferred couples, directly influencing the show's trajectory. Similarly, The Great British Bake Off contestants often share behind-the-scenes glimpses on social media, maintaining viewer interest even between episodes. This interactive element transforms the viewing experience, making reality TV more immersive and turning passive observers into active participants in the unfolding drama (Andrejevic, 2008).

The Power of "Liveness"

Live broadcasts add another layer of excitement, making audiences feel like they are part of a shared moment. Shows like Big Brother rely on audience votes to decide contestants' fates, while live events like The Oscars create global conversations as they unfold. The unpredictability of live TV—anything can happen!—adds to its appeal (Scannell, 2014).

Reality TV and Social Discussions

Reality TV frequently provokes discussions about politics, gender, and ethics in addition to providing entertainment. The portrayal of contestants, whether reality shows manipulate narratives, and the messages these programs convey are all questions that viewers raise. As an illustration:

Discussions concerning cultural representation in food media were sparked by The Great British Bake Off (Murray & Ouellette, 2009). Diversity in casting and gender roles are issues that reality dating shows bring up.

Reality TV is a powerful force in digital culture that reflects and shapes societal norms in many ways, making it more than just a guilty pleasure.

💡 Through social media discussion, live voting, and cultural debates, reality TV continues to change and demonstrate that viewers are just as much a part of the program as the competitors.

References:

Andrejevic, M. (2008). Reality TV: The work of being watched. Rowman & Littlefield.

Couldry, N. (2012). Media, society, world: Social theory and digital media practice. Polity.

Hill, A. (2005). Reality TV: Audiences and popular factual television. Routledge.

Kavka, M. (2012). Reality TV. Edinburgh University Press.

Murray, S., & Ouellette, L. (2009). Reality TV: Remaking television culture. NYU Press.

Scannell, P. (2014). Television and the meaning of 'live': An enquiry into the human situation. Polity.

0 notes

Text

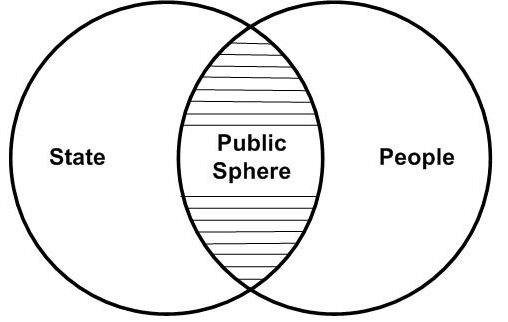

Public Sphere and Platform Vernacular

The internet has fundamentally changed our understanding of the "public sphere," a concept originally described by Jürgen Habermas. He envisioned spaces like coffeehouses and newspapers where people gathered to discuss societal issues. Now, social media platforms serve as digital public spheres, but they operate quite differently. These platforms are privately owned, their content is curated by algorithms, and they are each characterized by a distinct "platform vernacular"—the specific language, norms, and cultural practices unique to each site (Habermas, 1989).

The Digital Public Sphere: A New Landscape

Social media platforms differ significantly from traditional public spheres. They often blur the lines between personal and public communication. A tweet, for example, might be personal in nature yet have the potential to reach a vast audience. Furthermore, algorithms play a significant role in shaping online participation, often amplifying certain voices while silencing others. This selection process is frequently driven by engagement metrics rather than principles of democratic discourse (Pariser, 2011). Consequently, instead of promoting open dialogue, these online spaces can devolve into echo chambers, reinforcing existing viewpoints rather than challenging them (Sunstein, 2017).

The Nuances of Platform Vernacular

Each social media platform develops its own unique vernacular, or way of communicating and interacting. TikTok, for example, emphasizes trends, duets, and popular audio clips, creating a highly participatory environment. Twitter (now X) is known for its concise messages, "hot takes," and the pursuit of virality, often rewarding speed and controversy. Reddit fosters in-depth discussions within specialized communities, resulting in a distinct public sphere compared to Instagram, which prioritizes visual aesthetics (Gillespie, 2018).

Understanding platform vernacular is essential for effective online communication. A message well-received on LinkedIn (formal, professional) might be completely ineffective on Tumblr (casual, ironic, and full of inside jokes). This also has implications for online activism, where strategies must be tailored to the specific culture of each platform to be successful (boyd, 2014).

The Importance of Critical Engagement

Understanding the dynamics of digital public spheres—and the influence of platform vernacular on online discourse—empowers us to engage more critically online. Are we genuinely participating in a public discussion, or are we being influenced by algorithms? Are we conforming to a platform’s norms, or are we allowing those norms to shape our own beliefs? By understanding these forces, we can gain greater control over our digital interactions and contribute more meaningfully to online conversations (Zuboff, 2019).

References:

boyd, d. (2014). It's complicated: The social lives of networked teens. Yale University Press.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. MIT Press.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. Penguin Books.

Sunstein, C. R. (2017). #Republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media. Princeton University Press.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

1 note

·

View note