Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

W14: Hocks

Mary Hocks mentions the notion of hybridity in visual communication, which I believe is an essential characteristic when considering the relationship between verbal and visual text(s). Hocks acknowledges the importance of multimodal forms of communication, along with understanding text as hybrid. According to Hocks, the “new media and the literacies they require are hybrid forms” that are “verbal, spatial, and visual” (Hocks, 2003. p. 631). This made me think of a recent event that prompted me to investigate investing in another suitable car for the little family I brought with me to Albuquerque. On Thursday, December 9, I discovered that my girlfriend is pregnant, which prompted me to start my search for something economical, family-friendly, and dependable since we frequent El Paso, Texas throughout the year. I thought of Hocks because, well, at heart I am an auto enthusiast, so, I look for horsepower, style, and weight before considering the gas mileage.

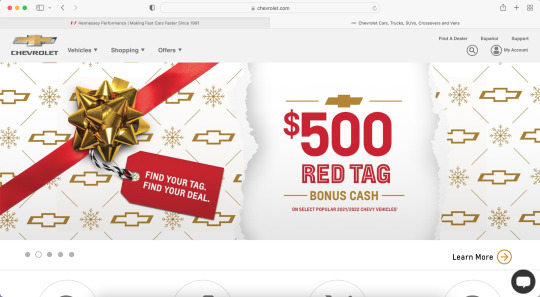

As I embarked on my journey to find us an economic SUV (as my girlfriend wanted me to do), I came across several dealership websites, and noticed a few things that relate to visual rhetoric–these websites use marketing as a means to appeal to their products. First, I noticed that dealerships and larger brands/makes (i.e., Ford, Chevy, Honda, etc.) use visuals to enhance their sales before allowing the user (me) to browse for, well, the things we initially wanted (e.g., dependability, economy, and style). What’s interesting is that certain websites (e.g., Chevrolet) do different moves while still relying on the text to communicate what the company’s website wants its audience to see.

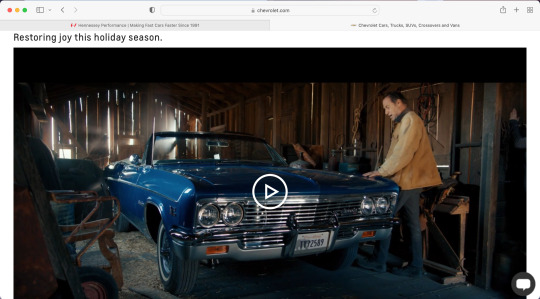

While shopping for a new vehicle, I found Chevy’s website of particular interest. Chevy’s decision to elicit a sense of wanting to touch an older model car–which they provide via a video towards the bottom of the page–elicits memories of wanting the heritage that comes with sports cars. I recalled Hocks arguing the following assertions in advocating for the perception of computers as visual artifacts:

The screen itself is a tablet that combines words, interfaces, icons, and pictures that invoke other modalities like touch and sound. But because modern information technologies construct meaning as simultaneously verbal, visual, and interactive hybrids, digital rhetoric simply assumes the use of visual rhetoric as well as other modalities” (Hocks, 2003. p. 631).

Aside from the car in the video being my ultimate dream car (1964 Chevrolet Impala), the video makes you want the heritage, power, and honor that comes with owning a Chevy, especially one of their sports cars.

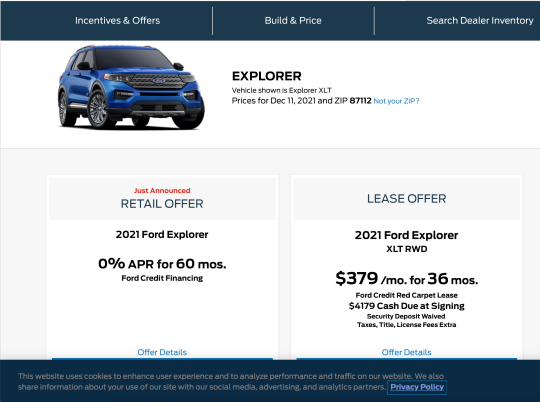

The company uses its clever design elements to capture the viewer’s attention (me), while also using text to identify and communicate options that would not likely be as effectively communicated through the use of visuals. Moreover, on Ford’s website, designers used a similar strategy to interact with viewers, in addition to using appealing colors to promote their line of SUV’s. For example, Ford uses their trademark color (Ford Cobalt Blue) on the 2021 Ford Explorer ST (subjectivity–it’s the sport option), while simultaneously including two purchasing options and not letting the audience lose sight of the Ford Explorer. Fixating the SUV, along with the purchasing options (subjectively) demonstrates how “visual and verbal elements work together to serve the rhetorical purposes and occasions” of the Ford company (Hocks, 2003. p. 631).

0 notes

Text

Week 13-Takayoshi & Self,

&

Bezemer & Kress

In discussing the role of medium, Bezemer and Kress in their (2008) article, “Writing in Multimodal Texts,” mention social contestation, which conceptually sheds light on why I chose to focus on the themes inherent in hip-hop culture this semester. The authors assert the following: “The expansion of Web-based resources, some freely available, may well lead to a decline in the use of the medium of the textbook. The consequences will be far reaching: semiotically, for instance, in changes to the uses, forms, and valuations of the mode of writing, socially through the potentials for semiotic action by sign makers. Such changes in media are always subject to social contestation. As one current example, walls and other surfaces (e.g., [underground] trains) are transformed into medium by graffiti artists (emphasis added) (Bezemer & Kress, 2008. p. 172-173). These assertions made me think of the train cars that are replete with examples of graffiti.

I would argue that Bezemer and Kress are accurate in their assertions considering how most of the language we used in high school only existed because of a push towards homogenizing language (i.e., the dominant discourse) to the extent where we had to create our own unique way of communicating, which eventually went underground because of our school’s sanctions on those caught in possession of sharpies, paint markers, or other materials ($500 fine, and a semester in alternative). The more my high school sanctioned and enforced the ending of graffiti on its surfaces, the more it moved underground, which demonstrates its reactionary movement as a symbol of change(s).

Finally, Pamela Takayoshi and Cynthia Selfe’s chapter on multimodalities provides a direct reference to/for the pedagogical need to incorporate elements of graffiti into our courses. As the authors assert, “Multimodal composition may bring the often neglected third appeal–Pathos–back into composition classes (which often emphasizes logos and ethos while devaluing pathos as an ethical or intellectual strategy for appealing to an audience)” (Takayoshi & Selfe, 2007). Further research should focus on the boundaries of multimodality: What counts as multimodal?

0 notes

Text

W12: Part II on Cozza

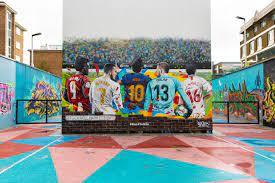

After looking back at Berger’s arguments and how I related them to graffiti, I chose to do a Google search of “Cultural Graffiti,” which resulted in some pretty interesting pictures of street art. This post differs from my last entry because I never noticed that public street art can communicate a strong, social message, while not fully advocating for social justice. For example, I found pictures of street art that focused on global terrorism, interstate warfare, and even oil prices. Whereas other searches resulted in art paying homage to entire nationalities (e.g., Mexico) and other art focused on paying homage to hip-hop’s famed legends (e.g., Notorious B.I.G., and Old Dirty Bastard or ODB).

I found these searches interesting because they appeal to pathos and they force viewers to reminisce on the collective memory of rap’s greatest legends. In other words, the public murals engage viewers, appeal to oppressed groups, and guide viewers in reinscribing the deceased rappers’ collective memory similar to the merits in which Cozza argues when describing students’ projects (e.g., Cozza’s discussion on Megan’s project). This is significant because the use of street art here is used to educate students on cultural, political, and pop cultural icons from the 1990s.

Arguably, these are my favorite types of murals because of their precise details and clever use of contexts and materials.

These go even further and touch on the topics and people directly related to one of my favorite rhetors–Robert Earl Davis Jr (DJ Screw).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 12–Gries & Cozza

During the creation of my final project in this course, I struggled with Laurie Gries’s notion of rhetorical “thing power” in relation to a “thing’s” rhetorical presence in an ecology. Theoretically, graffiti and hip-hop culture operate within a rhetorical ecology. According to Gries, interactions, encounters, and elements, in addition to “social flux or forces” and the networked nature (in a spatiotemporal sense) all constitute the happenings at play in a rhetorical ecology (Gries, 2016. p. 159). The presence, political messages, and overall nature of street art occupy the center of a rhetorical ecology–where its ontological significance is realized only in relation to the context in which it exists. I extend on and argue that Gries’s assertions apply to concepts outside of pictures and images because of their capacity to communicate, change, and rearrange publics, which results in the reception of its significance (or lack thereof) by the public (e.g., publics in the early 60s and 70s interpreted street art as the defacement of property). An example of this are high-rise, high-stakes or Heaven pieces, which are erected on higher canvases in efforts to maximize recognition.

In doing the final project for this course and finding ways to incorporate Gries into my argument, I learned that graffiti itself is political both in practice and by definition. According to Cozza, street art and graffiti provide access to valuable information to marginalized populations, in addition to providing “engagement in global matters” to underrepresented communities–all while existing as a strong symbol of social justice (Cozza, 15).

Arguably, street art and murals serve as forms of representation to marginalized groups within society (e.g., poverty-stricken areas, urban neighborhoods, and gentrification clusters). Using street art in the classroom benefits students by (1) providing students with “rhetorical knowledge and engagement in global matters,” (2) exposing students to rhetorical tactics and strategies, and (3) educating students on topics of “politics and history” (Cozza, 2015). Arguably, the images above resonate with social justice aims, and adhere to the principles of “representational images,” which (and in citing Foss) the image must have and do the following: (1) must convey ideas or concepts, (2) requires human actin in its creation or its interpretation, and (3) [the object] has the potential to “attract and engage viewers” (Cozza, 2015). Some of my search results were beyond impressive, and they all remind me of why I persistently pushed this topic till the very end!

0 notes

Text

Week 11, 13, and 14 on Hybridity:

Weeks 13 and 14 provided us with ample amounts of conversations regarding the relationship between visuals and text. I will start with Hill’s comments:

I have been discussing the difference between concrete objects, that exists or ever did exist. A picture of a unicorn can carry meaning because the viewer has been exposed to other representations of unicorns, both visual and verbal, and can associate the new representation with memories of those encountered previously. And, like words, visual representations can stand in for abstract ideas (Hill, 2004. p. 115).

Additionally, weeks 13 and 14 touched on the concept of hybridity, wherein text(s) and visuals complemented one another. At first, I was confused by notions of hybridity–I did not understand the purpose or role that it plays in visual rhetoric. However, and after I finished my final project, I noticed that the project itself was an example of hybridity and the need to further investigate how hybrid texts interact with the rhetor (me) and audience (Dr. Newmark/hypothetically CCCC audience members) in relation to the argument. In other words, I did not understand or know I was practicing a form of hybridity until I neared the end of the project where I used more texts to provide rich, descriptive examples.

The final project made me think about hybridity and the role(s) of textuality in contemporary composition courses–especially because this project is an example and form of communication. I discovered early on that I would not be able to include much written text in a visual rhetoric class. Therefore, I searched for images that best contextualized what I spoke about in the project. I found several themes on social justice, politics, and Black Lives Matter (BLM) Murals, which all included even more topics circling back to issues regarding intersections of race, gender, religion, and wages in the workplace.

0 notes

Text

W11: Hill

In Charles Hill’s “Reading the Visual in College Writing Classes,” the author argues for a pedagogy that allows for a visual element in composition courses, which is necessary for students as “social agents.” In this chapter, Hill argues that objective and subjective reality or realities cannot be separated from one another–our subjectivities frame, shape, and interfere with our perceptions of reality. Precisely, Hill asserts the following:

What the fictional Murray Siskind understands it that no visual perception is a pure apprehension of objective reality. Comprehending and interpreting any image, whether it is a barn seen through a car window or a painting of a barn, requires an active mental process that is driven by personal and cultural values and assumptions. When we look at an object, no matter how mundane, our perception of the object is filtered through, and transformed by, our assumptions about it and attitudes toward it, assumptions and attitudes that may be highly idiosyncratic or widely shared within the culture. Seeing a rusted car on blocks in someone’s front yard may signal any range of assumptions about the owner, whether the car is seen in a photograph or painting, or whether one is seeing the actual car. To use a quite different example, it is impossible for members of our culture to view a sunset without it bringing to mind a range of associations, from literary and other cultural sources. As Murray Siskind would say, “we’re part of the aura, and we can’t escape it” (Hill, 2004. 113-114).

First, this quote interested me because it identifies subjectivity as an active element in relation to human perception. This reminded me of optical illusions, specifically the “white and gold dress” debate. Whereas bloggers online still see blue and black, I see gold and white:

On another note, Hill interestingly argues that images have the potential to make arguments within themselves. Arguably, the dress resulted in arguments regarding its color, albeit I believe Hill is more concerned about the structure of an argument appearing through an image, which the dress clearly does not represent. However, I pondered for a substantial amount of time on the idea of the aura in relation to new generations and cultural artifacts.

Thus, because the aura is inescapable, our perceptions of reality influence much of what we encounter in our everyday happenings. I would argue that popular culture and new generations also contribute to, shape, and are shaped by perceptions of objects and cultural artifacts. For example, to those born after 1996, the videogame series Grand Theft Auto does not count as a significant cultural artifact. However, GTA’s cover art is iconic to those who experienced the first game on Gameboy (e.g., a handheld videogame), in addition to the billions of buyers who purchased the latest version: Grand Theft Auto 5. To these younger generations, the game is unheard of, and the cover art is just a cheap collage of guns, money, women, and cars. Thus, when new generations see old cover art, I have noticed that little respect or care is given for the cover art, and thus little value is given to the game itself. It’s different for older generations! For example, older and even newer generations would likely not categorize this as one of the greatest video games’ cover art. However, my generation would argue that this is one of the most symbolic cultural artifacts in contemporary popular culture. I would add to Hill’s argument and say that the aura is perspectival in the context of GTA’s cover art.

0 notes

Text

W10: Roberts

In “Visual Argument in Intercultural Contexts: Perspectives on Folk/Traditional Art,” Kathleen Roberts investigates folk art, and interestingly makes the argument that “images can argue” within the first sentence of the paper. Roberts argues the following: “Folk art is so named because of the value places on human creation. The process should require skill, so that appreciating a folk-art piece is to appreciate the artist as well as the art” (emphasis added) (Roberts, 2007. p. 153). Moreover, the author argues that the ways in which we think of culture should include an emphasis on its “performed” and “lived” experience. Arguably, taggers and “bombers” apply these principles to their work (e.g., Banksy’s public murals). Graffiti has these principles in its material happenings because it calls for “creativity that emphasizes artistic process, cultural tradition, and limited individualism” (Roberts, 2007. p. 153). Artists are aware of when, where, and what they are writing in relation to the contexts within which they contribute their art. In addition, graffiti artists must take into consideration the variables that exist within writing, such as: (1) audience awareness, (2) purpose, and (3) a means in which artists use space and appropriate (political) spaces in creating their works.

Arguably, graffiti artists craft their masterpieces with the use of cultural tools, which reminded me of Angela Haas and the ways in which she discusses wampum as hyptertext. Both [graffiti and wampum] are cultural (and arguably multimodal and digital) because of the ways (1) people use them, and (2) how they cannot be separated from the practices, people, and lived experience(s) of the cultures they serve. As Haas asserts, “To explain, ‘digital’ refers to our fingers, our digits, one of the primary ways (along with our ears and eyes) through which we make sense of the world and with which we write into the world” (Haas, 2007. p. 84).

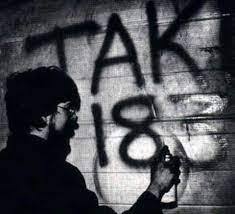

Graffiti in the 60s and 70s served as a vehicle for language (similar to wampum): It allowed subscribers of hip-hop to “write into the world” as a means of resisting the dominant discourse and culture (i.e., in the 60s and 70s, instances of graffiti became more apparent in New York City). The creation of such works cannot be removed from the context and culture within which it is produced, which is why New York is identified as the hub and starting point of graffiti as a practice and culture. The two rhetors below are credited with starting the graffiti movement during the late 60s and early 70s: (1) Taki183, and (2) CornBread

1 note

·

View note

Text

W10 III: Back to the First Entry

As a new, separate discussion regarding my first entry, I saw a YouTube video that reminded me of the confusion I had in writing that response. Because of this, I started investigating and searching through the comments until I finally found a video titled “1 Hour ASMR. Soap Only. Very satisfying relax sound. Compilation,” and I believe I just found my new hobby, and something that relates to Berger’s argument in one way or another. The videos show hands using what seems to be a knife cutting through perforated bars of soap. However, the full bar of soap is still intact, while the buttery-looking soap peels with ease. At first, I thought it was going to be a crazy representation of some person cutting their hand off (or something weird considering I saw a hand and a blade in the same frame). However, and after going to HOME to search for some ASMR Soap Bars (yes–they are real and they retail for more than a regular bar of soap), I thought of Berger’s assertions of fragmentation. Now, I am sure that I am not using the correct context in relation to the accuracy of Berger’s assertions, but if you take a picture and stop the video on a frame where the perfectly, buttery squares of soap are landing–this creates an immaculate image that elicits a need to spend money on these materials just to achieve that desired effect. Because of this image, I went to HOME and bought an “ASMR Lavender Kit,” and now I’m -$30 in the hole with a new hobby. To see the video, follow the hyperlink–it should be the first video that appears when searching “ASMR compilation.”

0 notes

Text

Berger II–Adding to his Previous Argument

Considering the role of and significance of typeface in Berger’s argument, graffiti artists and hip-hop practitioners in general consider the seriousness of typefaces when composing their works, regardless of the canvas type, record designs, and other related visual means of communicating. According to Berger, “typefaces play an important role in transmitting information, and the way a message is presented has a great deal of significance" (Berger, 1989. p. 109). Gang graffiti resonates with Berger’s point, along with more specialized graffiti typeface(s). In gang graffiti, rhetors often use colors, albeit their writing is messier and far less discernible when compared to typefaces like drip style. Arguably, students in FYC courses are adept, and even engaged with, different typefaces, which became apparent while I graded many of the portfolios for my English 1110 9 AM course. Students’ ability to use various typefaces reminds me of another high-risk, stylized form of writing that I used in the creation of my final project for this course. Roughly 30% of my time on this project consisted of toggling the typeface font options with different design elements (i.e., choice of color, background transparency, etc). The real value here is that I never knew how arduous it is to create PowerPoints from blank sheets on Microsoft Office.

For the project, I used a graffiti-style typeface throughout, while keeping the contents within a humorous yet professional space. In the project, however, I draw on JP Gee’s (2019) ideas regarding risk-taking, and I tried to use this to demonstrate how it is possible to slightly bend what we identify as “rules” in textuality and in an academic conference presentation. I used a template from one of my previous 4Cs conference visits (another risky behavior–I used one image per slide and got away with it during my presentation). However, I believe the important part [pedagogically] is to let students know they have flexibility in writing, which opens space for directed rhetorical decision-making, along with creativity. Moreover, I mentioned “try” in that statement because I started thinking about text and visuals, and how a lot of what we read towards the end of the course mentioned how text and visuals work together but did not attempt to cross the principles. For example, it would be interesting to see the ways in which intertextuality works within photographs, and how we can make such argument in the realm of other visual rhetoric components.

0 notes

Text

W10: Berger I

Week 10-Berger I

This semester, I chose to focus on elements of hip-hop in all three of my courses. For rhetorics of Oppression, I looked at song lyrics and their use as combatting oppressive rhetorics. In 530, I tried connecting the class as much as I possibly could with Critical Pedagogy and Theory–ultimately imbuing my syllabus with parts pulled from the theory. In this course, I focused on graffiti, which felt natural, interesting, and conducive to my overall focus on hip-hop culture–especially since I grew up around taggers and other friends who now do freestyles in their haircuts [as barbers] and other related materials and surfaces. In discussing unity, Arthur Asa Berger mentions the “Gestalt effect,” which he describes as an “aesthetic response that is greater than the sum of its parts,” noting how “the entire image may produce a response that is greater than would be produced by adding the various elements in the visual field” (Berger, 1989. p. 117). Berger argues that such phenomenon is the result of fragmentation or incompleteness. There is aesthetic beauty in pictures that add these elements. I believe one example of such “fragmentation” is the picture of a forest (below), which is unedited. For example, I Googled images of forests and found the picture below, which, arguably, is a fragmented photo in the sense that only a specific part of the forest is captured within the frame, whereas other parts would likely reveal different elements of the forest (e.g., a pond or water running through parts of the forest).

I am adding this section of the post late because I am still grappling with some concepts from the reading regarding Berger’s ideas, typefaces, and other design elements that “appeal to the eye.” These topics were difficult for me to incorporate in the current conversation. I struggled most with incorporating them without knowing if other operating systems accepted or ran the software requisite for the use of different typeface(s), which was frustrating overall (e.g., I tried downloading typefaces and some software programs did not support the font style).

This fragmented example of fragmentation relates directly back to graffiti because “There are no absolute rules in design and composition and the best designers and artists often violate rules” (Berger, 1989 p. 117). The “designers and artists” that Berger mentions share similarities with taggers and graffiti artists regarding design principles, albeit they blur the boundaries between art and defacement. Nonetheless, I argue that artists are rhetors because via the use of their craft, they have essentially mastered the manipulation and use of language. In other words, graffiti artists are rhetors because they know how to break established “rules” that act to determine and fixate the conversation and/or message(s) that artists try to convey. One of the recurring themes I encountered during the research phase for this course’s final concerns authorship, or in this sense, the responsibility for the erection of murals in random public space(s). For example, graffiti artists commonly share a style of “getting up,” which means they have arguably become experts and autodidacts in typeface, font, and other related design elements. Moreover, Berger asserts the following: “In thinking about design, one should first consider the effect desired and then work to achieve that effect, using whatever techniques are available. So, we work backward, from the desired effect to whatever can be done to generate that effect” (Berger, 1989. p. 117). The following image–I believe–puts Burger’s assertion into practice. Notice how the artists in these murals are precise about how the written letters are positioned, along with the outline of the work that (through their perfection of the trade) these graffiti artists have already mastered. Though the legibility and letters become difficult to discern, the style and design of masterpieces arguably calls for the rejection of conventional language rules wherein artists contest, disrupt, and demonstrate agency in the spaces where pieces are “thrownup.” It is important to note that even gangs demonstrate an adept use of language in creating their pieces, which is evinced by their choices in typeface, location, and color.

1 note

·

View note