Text

Fan Works Project Links

Fan Cookbook 1 (Dawntide): https://view.genial.ly/6557b1b8e5bec40011a9bfb3/interactive-content-a-coffee-tour-of-porthwarren

Fan cookbook 2 (Dawntide): https://archiveofourown.org/works/51633649

(Note on cookbook 2: this is published to my personal ao3 account; I'm an open book, and not one to feel shame around people who already know I'm a furry, but please be aware that if you happen to venture further on the page, you may find things more personal and gratuitous than anything you wanted to see from me. Again, I'm an open book, but it's a gentle warning.)

Interactive Fanfic 1 (Night Physics):

Interactive Fanfic 2 (Echo/Dawntide):

0 notes

Text

Fandom Game Initial Brainstorm

-You play as a black square on a white background, navigating a blank space with other squares (imagine them as similar to screensavers, bouncing off the sides and corners).

-"Fandoms" are differently-colored squares that enter the playing field at random, and if you run into one, you "catch" it and it attaches to you. For every fandom attached to you, new ones enter the board with increasing frequency

-Once attached, however, fandoms may detach unpredictably; the objective is to end the round with a certain high score that will allow you to move onto the next stage, which will be shorter and more intense

-Red squares are to be avoided: anti-fandoms are squares that do not attach and knock off a couple of others, toxic fandoms are squares that attach but do not count for points and corrupt other fandoms attached to you so they don't count for points either

-Different fandoms have different abilities: media fandoms (green squares) make you magnetic for other media fandoms, BUT can be corrupted without warning; sports fandoms (blue squares) do not detach but may make your media fandoms detach; music fandoms (yellow squares) will stay attached indefinitely unless more than one are gathered, in which case they will begin detaching more frequently.

0 notes

Text

Ethics Case Study, Zamii07

Looking at the situation through the rights lens, one could argue that both sides of the issue have a leg to stand on, though this doesn't justify it: First, Zamii had a right to the creation of fan art, and a right to represent the show's characters as she saw fit; on the other hand, "skinnywashing" is problematic as a wider trend, and the harassers felt they were defending one's right to be faithfully represented as fat. Through the virtue lens, the harassers used the virtue "accountability" to justify their organized harassment; whether this was good or not, the bullies felt as if they were acting ethically as virtuous figures.

The specific platform affordances that made it as bad as it became were tagging, sharing, and creation. Tagging allowed for sharing, in that it allowed the harassers to use these particular affordances to disseminate their anger more easily and efficiently, which gathered more people to harass the artist. Creation--as in, Tumblr as a platform valued individual creation and expression--allowed the harassers to make over 40 hate blogs specific to the artist, creating memes about them, and generally fanning the flames of the online dogpiling that went on.

0 notes

Text

Fan Autoethnography, Final Draft

Many such tweets have been made seeking to get to the bottom of this whole “furry” thing. I happen to be partial to this one.

Fandom, as I understand it, is a lot like faith: a means of understanding my experience in the world. I first received salvation when I was thirteen years old.

Imagine this: It is 12/21/12, the night the world is supposed to end. Your friend showed you a movie a few weeks before, which has since been echoing through you like a song stuck in your head. Your family goes to a Christmas market in Dade City, and looking around at the string lights everywhere and the decorations and the old friends running into each other by chance—you think of the Christmas song which describes the holiday as “that time of year when the world falls in love”—you feel as though you’re in the world of the movie. It wasn’t that it echoes through you; you echo through it. The world isbeautiful, you realize, as beautiful as your favorite movie, and you feel lucky to have found a place in it.

Fanart of two characters from the visual novel “The Smoke Room.” Artist unknown.

So you get involved. You don’t just look up fanfiction on an iPad you stole from your mother and feel as if your heart were exploding with excitement and sudden purpose until early in the morning (and no, the world does not end that night, but something inside you blossoms and you think maybe a world began); you do your best to live that sudden purpose. You get involved. You get into writing because you want to make other people feel the way the fanfiction makes you feel; you stand up straighter, laugh more at jokes, and settle into a new persona that might make others see you with the same awe with which you see the characters you love so much. You get involved.

The word hyperfixation is thrown around a lot in anecdotes like these, these days; though probably accurate, the word feels limiting. It feels more like what Didion wrote: we tell ourselves stories in order to live. In the fandom experience, one doesn't simply tell a story, or consume it; the story becomes like a hot tub, golden bubbling water into which you lower your body and are yourself consumed. And then you’re at peace.

A meme made by a friend, featuring one of our favorite characters, Ranzo LeVant from the visual novel “Dawntide.” The image is now my Twitter banner.

As an adolescent, I remember being awestruck at how welcoming this new side of the Internet seemed. I’d only known nerd culture in stereotype: fedora-clad men with greasy ponytails arguing which of them were “real” fans and which weren’t. I know now that division still exists in fandom circles, which are far from utopian—the role of capital-d Discourse in furry fandom, I’ve found, is like the electrical charge inside a thundercloud that might at any time explode into occasional lightning—but it did, admittedly, seem like a utopia, then. Fandom to me was a genuinely thriving literary and art economy in which everyone was making work for everyone else with little boundaries, assumptions, or requirements; and a space in which, with no entry requirements, people could simply gather to celebrate.

These were years I spent in conversion therapy; years during which I watched the openly-gay senior at my homeschool co-op be barred from graduation; years which, as a pastor’s kid, I spent in the panopticon, surrounded by people who felt close to me though I didn’t feel close to them, keenly aware that there was some invisible difference in me. I dreamt all the time of kissing boys. Fandom was psychological compensation for a kid who just couldn’t come of age in a safe or “normal” way in his environment and was pushed into the worlds he enjoyed in his head. It meant more to me than I could have known, then, to read a fanfic in which two men kissed who I felt I knew, and to be surrounded by people similarly overjoyed. I lowered myself into the hot tub and let the narratives, fan content, and art that sustained me render me weightless. I was only an observer in adolescence, but fandom then taught me everything I’m passionate about today.

A drawover of a friend’s fursona on Discord.

These days, I’m no longer an observer. In fact, I’ve grown to participate as a hobbyist more intensely than I ever thought I would: for example, I thought in high school that fursonas (fursonae?) were for people who genuinely believed they were non-human on some metaphysical level—people I now know as “Therians.” But these days, mine are a great joy of my life. I’ve found the fursona is whatever you want it to be, nothing more than a character you create for yourself. According to Jung, the persona is a mask; furry or not, we all don masks online. What’s the harm in giving yours a tail?

In time, what you pay attention to, you eventually emulate. Having spent my thought-forming years online, inundated by images, I and other Gen Z-ers tend to think in categories of images rather than in images themselves; the phenomenology of the image is such that you, in your own diffuse and intangible way, become the image through emulation. This is self-actualization. (Egregious oversimplification, I know, but I’m no psych major.) As a furry—dwelling upon anthropomorphic images and aesthetics—I self-actualize in different ways, now. Which affects how I experience the world, what I want out of life, or how I want to be perceived. I find writing is more fun when in my head there’s a limber raccoon-guy doing it in my place; cooking food and joyfully tasting my creations is more fulfilling when, holding the spoon I am holding, is a badger.

Myself and a badge of one of my fursonas, which I commissioned to wear at conventions.

And then there is the convention. If the fandom experience is lowering oneself into a narrative as into a hot tub, the convention is the literal lowering oneself down. Word made Flesh. The etymology of “convene” is, simply, “to come together”; I’ve spent my whole life convening around kitchen tables, car rides, restaurants, and airport gates. So have you. But there’s something more beautiful in it that can’t quite be put into words when everyone who’s in the room shares the same tender, intimate secret. I mentioned before growing up feeling invisibly different; only on the convention floor, I’ve found, am I really myself.

People in general, I feel, are starved of spaces devoted to celebration. We seem to have deluded ourselves into thinking that joy has to be earned. I find a lot of value in faith communities of any stripe for this reason. Fandom, as previously mentioned, is to me a means of understanding my experience of the world, and a reason to celebrate it; faith, I’ve found, is no different.

Stickers on the stop sign outside the Rosemont Hyatt on the third day of Midwest Furfest 2022, the largest furry convention in history.

At Furry Weekend Atlanta 2022, the main hotel had a soaring atrium nearly 50 floors up. The dashingly cute-in-a-nerdy-way boy who would eventually become my beloved and I raced to the top, and as we looked down from heaven to earth, a group of fursuiters on the ground floor began to howl as if calling to us. Their joyful cries echoed about the building. I remember thinking if I’d stepped off the forty-seventh floor balcony then I’d float the whole way down.

Art on a window at a room party during Furry Weekend Atlanta. Our dancing would soon generate enough heat to fog up the windows again; new artists would draw new art, and new writers new words. The condensation dripped in long, slow lines from our handiwork. We do these things in order to live.

@officeofdocmalone

#com255

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

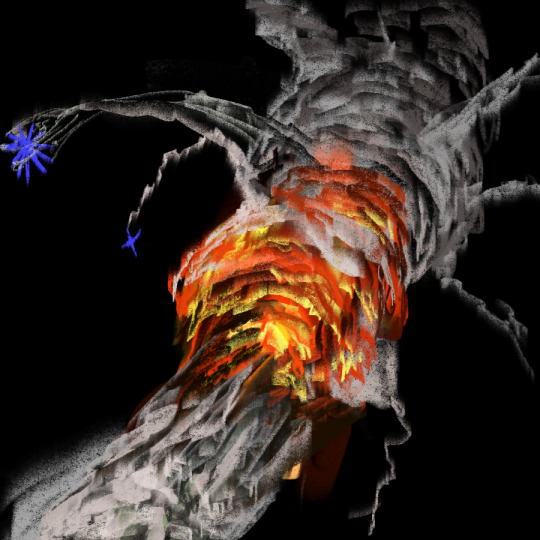

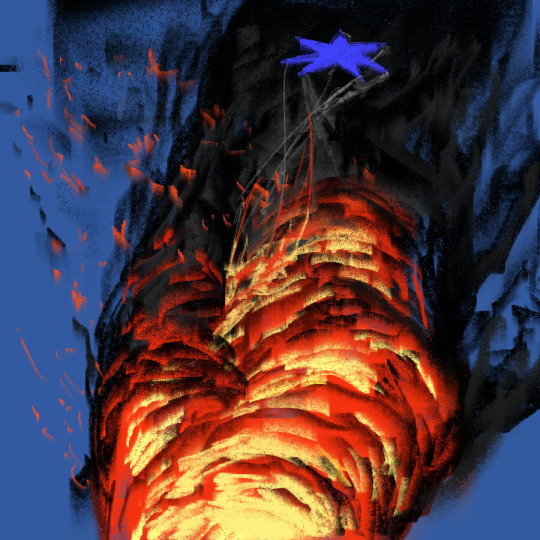

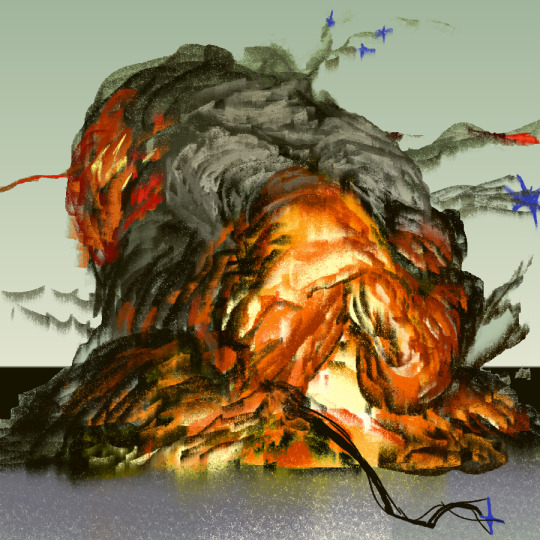

'Gone Cuckoo' - January 5, 2021.

&

four explosion studies from March 11, 2022.

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

Joel’s Fan Autoethnography

Joel’s Fan Autoethnography, First Draft

Reflection:

My experience with furry media is different from other media experiences in that—though I can’t quite explain why—one makes me want to involve myself, and the other doesn’t. It’s a question of emotional engagement: I could watch the most heartwrenching or exciting non-anthropomorphic movie and have the same emotional experience as the most mild anthropomorphic movie. I remember once, in a furry Discord server, a friend of mine was reading The Divine Comedy for all who wanted to listen, and a straggler came in; after the Inferno concluded, he admitted to us: “It would be good if it had gay furries in it.”

I spent my childhood, a pastor’s child, in the panopticon: hundreds of laypeople who knew me and knew details of my life more intimate than I’d ever shared, free to indulge in a connection they felt to me but I did not feel to them. These people wanted to involve themselves in me; meanwhile, I only wanted to involve myself in my own little worlds (the movies I watched, the video games I played, whatever media I had at the time). These worlds, even from childhood, were more beloved to me if they were anthropomorphic in nature. This is to say my attachment to anthro IPs is that they have been, my whole life, a secret place for me.

The way this affects your identity can’t be described, but you know it when you see it. And it becomes most obvious to me when I come home from spending time with my church-friends to hop online and spend time with my online furry-friends. My faith is on the outside of me, known by everyone, but my attachment to anthropomorphism is deep inside me; I can make relationships with furries more easily and ecstatically because they share the secret place with me, and know what it is to be invisibly different in some way their whole lives. And together, we flourish. It would be better with gay furries in it.

Analysis questions:

I think the “us vs. them” mindset exists still, but takes different forms through discourse: proshippers and antishippers (terms which I’d be lying if I claimed to understand what they mean), for example. The Internet, in my opinion, has democratized fandom to a certain extent—at any rate, at least made it more accessible and shareable— and one result of this is complex, intersectional divides based on minor differences of opinion. It feels less like a binary now than in fandom stereotype, though, and more like the constant electrical charge in a thundercloud that may or may not explode into occasional lightning.

As for myself, I try and keep myself in the cloud without keeping too much of a charge; however, there’s a difference between a rapist/neonazi/what have you taking an outspoken place in the fandom who needs to be ejected, and someone who disagrees with me on matters of ick and preference. In fandom spaces, I enjoy what I enjoy and try to avoid what I don’t.

2: In my opinion, fandom is an adjective for the “obsessive loner” and a noun for the “hysterical crowd.” A crowd can’t be hysterical if the people comprising it aren’t obsessed; fandom on one’s own is a characteristic, something that separates the loner, a la stardom, but in a crowd it’s a noun a la kingdom. This is to say, for me, they are the same thing, and therefore I’m not sure if Jensen’s thin line exists at all.

In distinguishing “normal” and “excessive” fandom, I prefer Jessica Ruth Austin’s take, which argues furries’ behavior separates into “hobbyists” and “lifestylers.” Neither are excessive or conservative, but simply characteristic. Lifestylers, especially from the outside, could be called the “excessive” ones—many engage in therianthropy, for example, which quite literally changes their basic human behavior and therefore further alienates them from social norms (a slightly maybe-inappropriate anecdote: once I slept with a therian at a convention who made animal noises in bed). I’d consider myself a hobbyist, or the closest thing to the “normal” fandom, in that I engage with it as a hobby: I participate in fandom commerce, I enjoy the art and writing, and I regularly discourse about the fandom itself, but I can’t see myself making it a capital-l Lifestyle in any specific way. Furry fandom is something I love dearly; nothing more.

3: There’s a funny social norm among furries—generally known to be a queer subculture, often made up of queer and neurodivergent people—in which friends, when made online, first share nudes; then, they share information about where they live if the friendship persists after a few months; then, if one is lucky, they might learn their friends’ real names after a couple years, and if they are best friends or lovers, they’ll learn last names, too. Anonymity in the online furry fandom usually allows people to show their most intimate parts first, and the everyday parts last.

On the flip side, there’s no such anonymity in a classroom; it affects the way I speak and write about the fandom because I must be seen from the outside first, and also discoursing openly about species-genitalia preferences in porn would likely land me in the Dean’s office, eventually.

4: Fandom has one hundred percent been psychological compensation for me, and it’s hard to imagine a way in which it’s not. Parasocial interactions carried me through adolescence, in which I was a young queer kid with all the tumult and anxiety of puberty with none of the support systems—for example, my first two years in high school were spent in conversion therapy offices. So it was more than just exciting, or comforting, to read fanfiction about two men kissing who I felt like I knew; it was affirming. Fandom put the world, for me, in terms that made sense according to my experience.

5: There are, as with any subculture, words that only make sense to furries (sonas, suiting, poodling, and therians, to name a few that come to mind), but I can’t say it bleeds into real life, for me. Unless it’s relevant to the conversation in some way, I make it a point to not use fandom language in non-fandom spaces.

0 notes

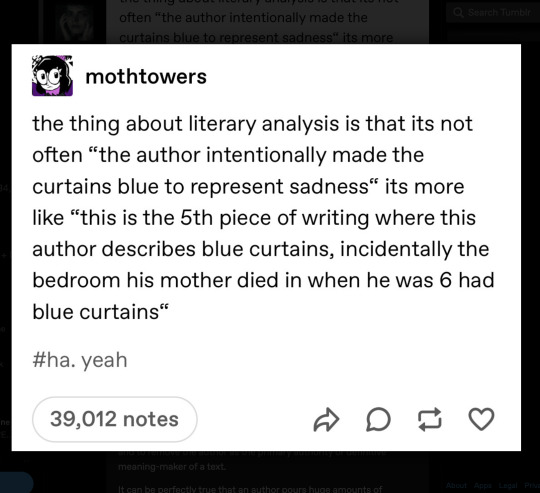

Note

Hi! I saw your post about the blue curtain thing and I was wondering what was wrong with their interpretation. I haven't taken an english/lit class in years so a lot of it has slipped my mind, and the way they explained it seemed to make sense to me (especially because I tend to intentionally do something similar for imagery in my own writing).

I just posted a pretty long explainer a second ago about this because obviously I was being flippant when I posted the original screenshot, but basically: there's nothing inherently wrong with using an author's biographical details to inform an interpretation of a piece of literature. Death of the Author is something else entirely. Some people who have never read Barthes' original essay and have maybe only heard the phrase or concept seem to think that Death of the Author is a methodology in which you ignore the author's life in favor of your "own interpretation," which is somehow always right. This could not be more wrong. But to step back, let's talk about why that original post was limiting to the practice and art of criticism (I'm going to use this instead of 'wrong') because that was your question.

At the core of that original post is, in fact, basically the same limited line of thinking present in the post I was talking about. (Btw no shade to OP–I care more about the 40k people who seem to agree with them, they might have changed their mind or not articulated themselves well, I've been there). Let's look at the original curtains are blue post and this post side by side.

Putting the rest of this under a cut because it gets long

The left is a version of the original idea in the "curtains are blue" post, and the right is the post I had an issue with which seems to basically be saying that real academic literary analysis doesn't actually try to match color symbolism to meaning, and instead focuses on autobiographical details of the author's life.

If this is true to OP's experience or the experience of those reblogging the post, I hope they high-tail it out of whatever program they're studying in. The issue with both of these posts, besides their general anti-intellectual undertone, is actually their emphasis on "correct" or "real" interpretation of a text, or one that is understood as "right" by some kind of invisible cabal of criticism-theory referees who all want to tell you "what the author really said." This is, among other things, a very juvenile approach to criticism. I think the reason that this type of sentiment is so popular on tumblr is that, frankly, a lot of people on this website are in high school or early college, and have an adversarial relationship to their English teacher/professor, who grades them on how well they can analyze a text based on sometimes arbitrary criteria. It makes sense that they would see themselves being graded on their criticism as "right" or "wrong" and interpret that there is such a thing as a single interpretation of a text that is "right" or "wrong."

However, that's not really what is or should be happening in upper-level/higher education. A high school English teacher trying to teach their students about color symbolism in the Great Gatsby is simply trying to impart one possible methodology of criticism to their students and enable them to repeat the same basic critical moves that one critic, at one time, has made, because grasping the basic ability to adopt a methodology and employ it is a foundational skill for analysis. However, public schools in America can't and don't take the time to explain that this is a methodology, so many students who are tumblr-aged walk away with this idea that their English teachers or even their professors have an extremely narrow view of what is "true" in a text. Often, exposure to one methodology will leave them with the idea that this is the correct methodology, when what they should have been taught first is that obsessing over what is "correct," especially related to truth from the author, is the one thing you shouldn't do.

This is why the second post is just as bad: it says that actually, it's not symbolic interpretations from the author that matter (as in 'the author meant for the curtains to just be blue'), but an author's biography which, buried under psychoanalytic layers, can be revealed as a generator of meaning (as in 'the author's mother died in a room with blue curtains'). Both of these things are irrelevant because they, probably through the above process of intellectual alienation caused by grades I mentioned above, are focused on what the author intended as being a source of truth within a text.

This is what Death of the Author makes an attempt to deconstruct, and why I mentioned it in my original post. Barthes wrote his essay at a time when theory and criticism in general was undergoing seismic shifts following two major world wars & a huge variety of other cultural undercurrents in middle of the 20th century. Many things that had been taken for granted up to that point were suddenly being reconsidered, in particular the idea that texts, art, or even language itself has a central "truth" or meaning. Massively simplified, this is one of the core tenets of post-structuralism, and you can definitely say that Barthes was a post-structuralist thinker.

When Barthes wrote that the death of the author is the birth of the reader, he was simply pointing out that the assumption many centuries of Western criticism is built on–that the author is the primary meaning-maker within a text, simply because they wrote it–is wrong. I believe this is true. Some people say death of the author is a "methodology" of criticism, but to me it's actually more like a door you have to walk through in order to do really good criticism. If you free yourself from the idea of a "correct" interpretation of a text driven by authorial intent, what you're left with is the really thrilling, life-giving work of criticism: drawing connections from within and without the text, and treating it as a living document whose meaning changes over time.

What I think people don't realize is that poststructuralism, either formally or in practice, is the basis for most of the literary theory we embrace and consider valid. That is NOT to say that some French dude in the 1950s invented feminism or post-colonial theory, or even paved the way for it. Instead, you could easily say that marginalized people were already approaching critical analysis in a variety of ways based on their lived experiences, and it was the academy which had to catch up. There are a lot of more complicated theoretical thoughts people have had on this, which aren't relevant here really. But I think it's worth pointing out that Death of the Author is, by my measure at least, very good to do, and is VITAL to do if you've spent most of your adult life having weird, watered-down versions of symbolic, biographical, or psychoanalytic theories of interpretation pounded into your head by overworked English teachers.

In summary: the reason we engage with texts at all is not to find a single meaning. It's not to prove out what the author said or what they didn't say. Instead, when we engage with literary criticism, our goal should be to simply say something as clearly as we can, based on the methodologies available to us. To ask "What is this? What is it doing? How is it doing it, and why do we care?" is a fundamental, beautiful question and the source of pleasure to me as a reader. Art isn't autonomous, and exists in our lives criss-crossed with social and political forces which change over time. When we can untangle the knots around a work of art, we discover ways to articulate ideas that might be impossible in other contexts. To only untangle the knot of authorial intent does ourselves, and the text, a disservice.

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

A good camera, a proper photoshop crop, and no telegram compression, and I'm super proud if this.

Super Dance Hall Scene - Acrylic on canvas - Kyle Powers, 2023

31 notes

·

View notes