Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

JULIE AND CAROL AT CARNEGIE HALL, from left: Carol Burnett, Julie Andrews, in rehearsal. Photo: George E. Joseph/TV Guide/courtesy Everett Collection

86 notes

·

View notes

Photo

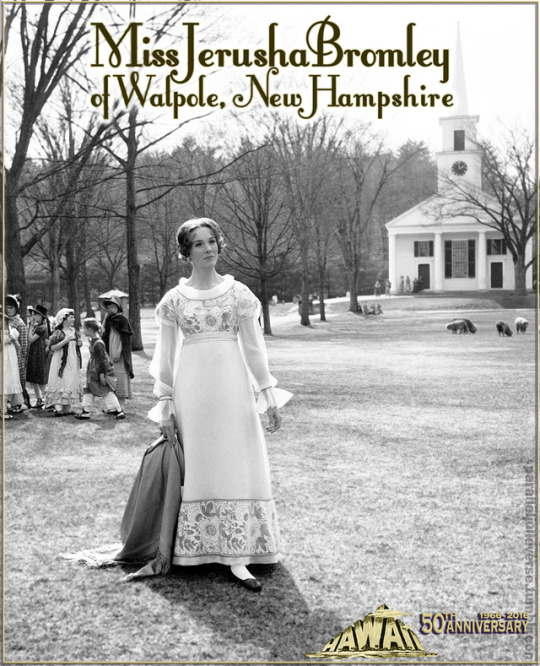

“[A]nd then he gaped, for coming down the stairs and into the room was Jerusha Bromley, twenty-two years old, slim, dark-eyed, dark-haired, perfect in feature and with gently dancing curls which framed her face, three on each side. She was exquisite in a frail starched dress of pink and white sprigged muslin, marked by a row of large pearl buttons, not flat as one found them in cheaper stores, but beautifully rounded on top and iridescent. They dropped in an unbroken line from her cameoed throat, over her striking bosom, down to her tiny waist and all the way to the hem of her dress, where three spaced bands of white bobbin lace completed the decoration. Abner, looking at her for the first time, choked. ‘She cannot be the sister they thought of for me,’ he thought. ‘She is so very lovely.’” - James A Michener, Hawaii (172-73)

Sources:

Michener, James A. Hawaii. New York: bantam, 1966.

© 2017, Brett Farmer. All Rights Reserved

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

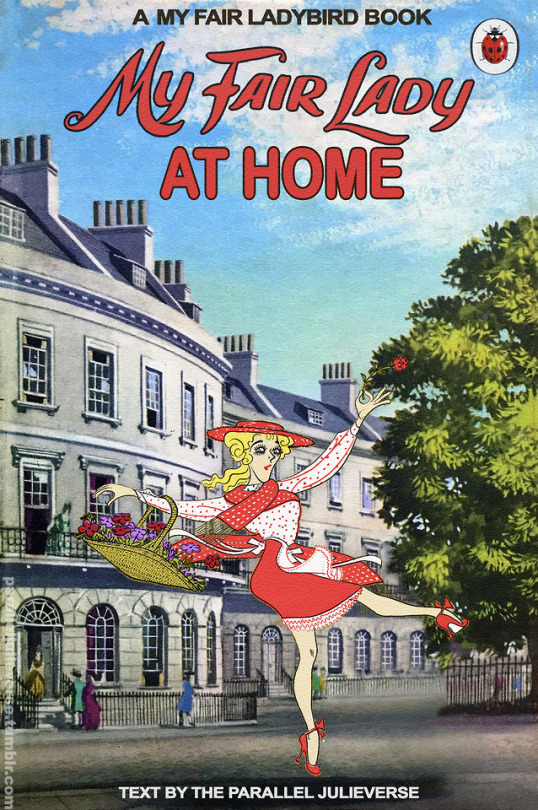

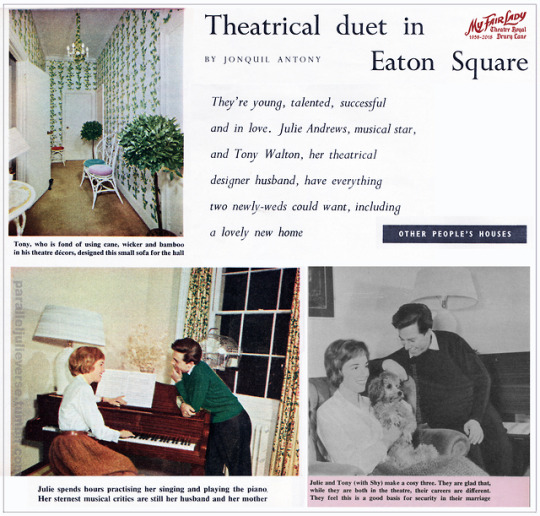

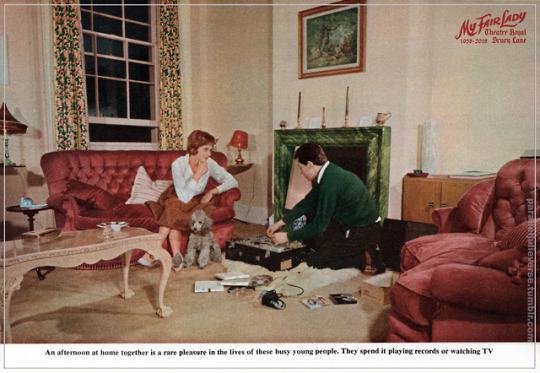

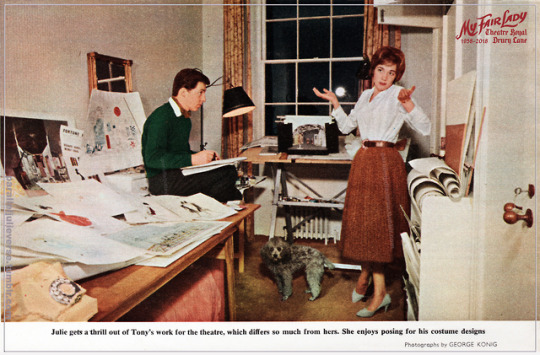

Following our recent posts marking the 60th anniversary of the wedding of Julie Andrews and Tony Walton, here we shine a brief spotlight on how the newlyweds were covered by the media in the early years of their marriage. Their May 1959 wedding was a definite high-water mark of media exposure for Julie and Tony but public interest didn’t end once they’d walked down the aisle. Newspapers and magazines continued to feature regular stories and photos about the ‘happy couple’, detailing what they were up to and how they were adapting to life as husband-and-wife.

Much of the coverage presented the newlyweds as a quintessentially modern couple who were combining the twin demands of dual careers with companionate marriage. A multi-page profile in the January 1960 issue of British women’s magazine, Housewife serves a good case-in-point. Essentially a ‘celebrities at home’ pictorial, the article marshals the couple’s “delightful new home––a large flat overlooking Eaton Square––to which they went when they were married eight months ago” as a symbolic expression of the blended amalgamations of marital domesticity (Antony: 38).

The “Andrews-Walton flat is a combination of their two careers,” the article chirps, “Julie’s piano has a prominent place and one room is made into Tony’s studio” (Antony: 40). Elsewhere it describes a cosy everyday scenario of domestic give-and-take as “Julie spends hours practising her singing” with Tony acting as one of her “sternest musical critics,” while Julie in turn “gets a thrill out of Tony’s work for the theatre [and] enjoys posing for his costume designs” (38-39). The image painted here is a transactional blend of conventional married home-life with newer forms of egalitarian coupledom: “two young people––both so young and in love––embarking on a duet” in “their lovely new home…a good basis for security in their marriage” (40-41).

Other profiles were considerably less blithesome. A recurrent refrain in a lot of the media coverage of Julie and Tony’s marriage was the perceived challenges faced by a couple in which, as one early newspaper report put it, “the wife’s name has embarrassingly eclipsed the husband’s” (Wilson: 10). In an era still tethered to orthodox notions of male breadwinners and female homemakers, a union in which the wife assumed greater professional and financial prowess than the husband was sufficiently novel to evoke both curiosity and, at times, unease.

In the newspaper profile just mentioned, Cecil Wilson (1959) strikes a note of thinly-veiled anxiety when discussing what he apprehends as a gendered dilemma in the couple’s marriage. Titled “How Not to Be Known as Mr Julie Andrews”, the article asserts a very traditional view of marriage in terms of masculine dominance and feminine support. “No man could have done more in less time” than Tony Walton, it proclaims, “to rise above the reflected glory of being ‘Julie Andrews’s husband’ or, worse still, the ignominious label of ‘Mr. Julie Andrews’” (10). “Since his childhood sweetheart from Walton-on-Thames consolidated her…stardom in My Fair Lady, he has firmly established the name of Tony Walton by designing four West End shows…[and n]ow, to give Julie Andrews further pride in being known as Tony Walton’s wife, he has gone into management” as a theatre producer (ibid.).*

It is a testament to Julie and Tony’s fortitude and well-grounded emotional security that, for the most part, they deflected such concerns as immaterial. Responding to a reporter’s question about how her status as “one of the country’s wealthiest young actresses” impacted her new married lifestyle, Julie demurred: “I don’t know how much I’m worth…We haven’t a car, although I hold a licence. But Tony holds the important licence, the marriage one” (Hickey: 3). Later, on the eve of her departure for New York to start rehearsals for Camelot, Julie mused further on the ambivalent demands of career and marriage: “Of course it’s nice to get back to work. I love the stage. But what I really like and what I want to do is to settle down and be plain Mrs. Walton” (Tanfield: 12).

For his part, Tony Walton struck a particularly mature and, for the time, progressive attitude to the unorthodox dynamics of his and Julie’s marriage. When asked in a 1959 interview if he experienced “professional jealousy” of Julie, he replied with categorical pragmatism: “Not a bit. After all, Julie has one career and I have another. But I still wouldn’t rank my fame with hers” (Wilson: 10). It was a consistently balanced approach he maintained––at least publicly––right throughout the marriage, even after Julie had graduated to the exponentially increased fame and fortune of film stardom. “[T]he embarrassments people see for me are easily coped with because they’re so absurd,” he remarked in a 1966 article, “I’d be stupid if I let them affect me” (Leslie: 8). If there is any problem, he ventured in an admirably democratic take on modern marriage, it is

“who at any one time is going to be the support. I don’t mean financial but emotional––which is the basis on which the whole marriage is built. When Julie and I were both in the theatre, and she was rehearsing at something and I was working at something else, the pressure times would swing back and forth between us. And at times I’d find myself taking on an almost feminine role, trying to calm, soothe, protect or whatever. And then as soon as I was deeply involved and under pressure then the roles would be reversed. I think if I were an over-dominant kind of male I’d find this situation harder to cope with. But neither of us is over-poweringly masculine or over-poweringly feminine” (ibid.)

That the marriage of Julie Andrews and Tony Walton ultimately didn’t last is a matter of historical record. Following extended periods of separation, the two officially filed for divorce in November 1967, eight and a half years after they were wed (”Julie Andrews Suing”: I-23). But the pair have, by all accounts, maintained a strong and enduring friendship, even after both of them found and subsequently married new partners (Robins: D-6). In fact, Julie is fond of recounting how Tony and his second wife, Gen LeRoy-Walton, affectionately refer to her as “our ex” (Andrews: 323). “They’re best friends and they gang up against me,” explains Tony Walton of the relationship between his former and current partners (McDonnell: 3D). As Julie observed in a 2001 interview: “[T]he divorce was extremely sobering but I’ve known [Tony] since I was 13 and he was 12, and you cannot undo that knowledge” (Birch: 16).

Notes:

* This kind of angst-ridden discourse about the perceived gendered power imbalance of the Andrews-Walton marriage intensified once Julie made the move to Hollywood and the even greater success of global film stardom. “When a wife starts earning much more money than her husband,” wrote one especially egregious example, “the marriage is not long for the lasting” (Shearer: 15). Such sensationalist commentary was evident even in international reports.”Julie Andrews and her prince-consort” was how one French-language article billed the marriage (Von Cottom: 22).

Sources:

Andrews, Julie. Home: A Memoir of My Early Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008.

Antony, Jonquil. “Theatrical Duet in Eaton Square.” House Wife. March 1960: 38-41.

Birch, Helen. “Truly Andrews.” Daily Telegraph. 7 December 2001: 15-16.

Hickey, William. “For Julie it’s the Beginning.” Daily Express. 8 August 1959: 3.

Jordan, Ruth. “No Fashion Fuss for Julie.” Woman’s Journal. December, 1959: 26-27, 134.

“Julie Andrews Suing Designer for Divorce.” Los Angeles Times. 15 November 1967: I-23.

Leslie, Ann. “Beating the Hysteria: ‘Mr. Julie Andrews’.” Daily Express. 19 April 1966: 8.

McDonnell, Brandy. “Tony Time.” The Oklahoman / Sunday Life. 27 May 2018: D1-D3.

Robins, Cynthia. “When Art and Love Meld Successfully.” San Francisco Examiner. 6 September 1992: D-6.

Shearer, Lloyd. “When a Wife Earns More than a Husband.” Parade. 9 July 1967: 14-15.

Tanfield, Paul. “My Year of Bliss…by Julie Andrews.” Daily Mail. 18 August 1960: 12.

Von Cottom, Joseph. “Julie Andrews et son prince-consort: le pitoyable drame des maris de vedettes.” Ciné-Télé-Revue. 4 August 1966: 22-23.

Wilson, Cecil. “How Not to Be Known as Mr Julie Andrews.” Daily Mail. 24 September 1959: 10.

Photographs by John Dixon, George Konig, and anon.

© 2019 Brett Farmer All Rights Reserved

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“I would like to say my warmest congratulations to you, ma’am, and thank you” - Julie Andrews on the occasion of the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee June 2022

As Britain and the Commonwealth launch the offical Platinum Jubilee Central Weekend to celebrate the remarkable 70 year reign of Queen Elizabeth II, it is only fitting that one of the first televised tributes to be broadcast should be from Dame Julie Andrews.

A loyal monarchist – “I admire Her Majesty very, very much” (Spencer 2020: 7) – Julie has a lifetime of associations, both professional and personal, with the British Royals. One of her earliest billed performances was at age 11 in 1946 when she sang for Queen Elizabeth, wife of King George VI, at London’s Stage Door Canteen. It would be the first of many royal performances and engagements over the ensuing years, some of which are showcased above.

The honour was returned by the Palace in 2000 when Julie was officially made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire as part of the Queen’s Millennium New Year’s Honours List. At the investiture ceremony in Buckingham Place, the Queen is reported to have said to Julie, "I’ve been waiting a long time to see you here!“ (Meyer 2019).

Sources:

Andrews, Julie (2008) Home: A Memoir of My Early Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Meyer, Dan (2019) ‘Julie Andrews Says She Came Crashing Down While Filming Mary Poppins’, Playbill.com, 21 October.

Spencer, Amy (2020) ‘Julie Andrews’, Parade, 13 December: 6-7. © 2022, Brett Farmer. All Rights Reserved

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Local Walton girl makes good: Community celebrity appearances by Julie Andrews as covered by The Surrey Herald in 1952.

Sources:

‘Local celebrity opens school fete’, The Surrey Herald, 4 July 1952: 5.

‘People and Places.’ The Surrey Herald, 18 July 1952: 6.

‘Walton’s New Youth Centre’, The Surrey Herald, 31 October 1952: 5. © 2022, Brett Farmer. All Rights Reserved

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From the Archives: ‘Shall I be Mum?’ Julie Andrews having tea with mother, Barbara, in the family home on the young star’s return from New York, 1 October 1955.

In his classic treatise on photography, La chambre claire / Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes (1980) argues that the elemental power of a photograph, its ‘special genius’, lies in its unique combination of ontology and subjectivity. The mechanical nature of photographic reproduction endows photos with a ‘having-been-there’ quality, a frozen moment of time and space, that sustains both cognitive curiosity and emotional poignancy. Barthes calls the former dimension the studium, the historical and cultural ‘infra-knowledge’ that a photograph provides, its capacity to render richly descriptive details of time and place. The second dimension is more intimate in nature and it is what Barthes calls the punctum, a Latin word meaning wound, sting or cut (the same root for English words like puncture and punctuation). It is the aspect of a photo that affects us emotionally and moves us in ways that can be deeply personal, even idiosyncratic. The punctum, writes Barthes, is the ‘element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me’ (26).

This 1955 press photo of Julie Andrews and her mother is a compelling evocation of both Barthesian axes of photographic allure: observational studium and affective punctum. In terms of the former, much of the immediate interest of the image comes from the glimpse it provides of celebrity home-life. An example of the popular photographic genre of ‘stars-at-home’, the image trades openly on the voyeuristic lure of peering into the private world of a public figure. In this case, Julie had just returned to England after her triumphant star-making year in The Boy Friend on Broadway, and the image accentuates the interplay between the extraordinariness of her newly-minted international celebrity – all radiant cosmetic smiles and neatly-tailored tweed suits – with the disarming ordinariness of the surrounding domestic mise-en-scène.

Indeed, decades later, the photo is significant for the added historical insight it offers into Julie’s beloved childhood home, the Old Meuse. Between the cottage ware teapot, floral chintz armchair, and Axminster rug, the photo is a veritable compendium of mid-century English suburban style. The rows of neatly-lined leather-bound books, silverware ornaments, and vase of cut flowers in the background add a further touch of aspirational petit-bourgeois respectability. And, zooming in to the plate of sweet biscuits on the tea tray, it looks as if Barbara even broke open a box of Huntley and Palmers Assorted Creams for the occasion!

But what possibly engages most in the photograph – and what pushes the image squarely into the affective realm of the punctum, at least for this viewer– is its weighted staging of mother-daughter relationality. Other than a homecoming, it was Julie’s 20th birthday and the shot fairly pulsates with the poignant ambivalence of generational succession. Hovering behind and above Julie, Barbara recedes into the background, one hand seeming to urge her star daughter forward, while the other appears to hold on to her. Then, as if in a chiaroscuro expressionist film, Barbara’s shadow is projected larger-than-life on to the wall of the Old Meuse.

Julie has commented widely on the close but complicated relationship she had with her mother. ‘My mother was terribly important to me,’ she writes in her 2008 memoir, ‘and I know how much I yearned for her in my youth, but I don’t think I truly trusted her’ (18). Taken almost 67 years ago, this photo speaks poignantly to those conflicted dynamics, if not to the knotty emotional interplay at the heart of all parent-child relationships.

Sources:

Andrews, Julie (2008) Home: A Memoir of My Early Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Barthes, Roland (1980) Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by R. Howard. New York: Hill and Wang.

© 2022, Brett Farmer. All Rights Reserved

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

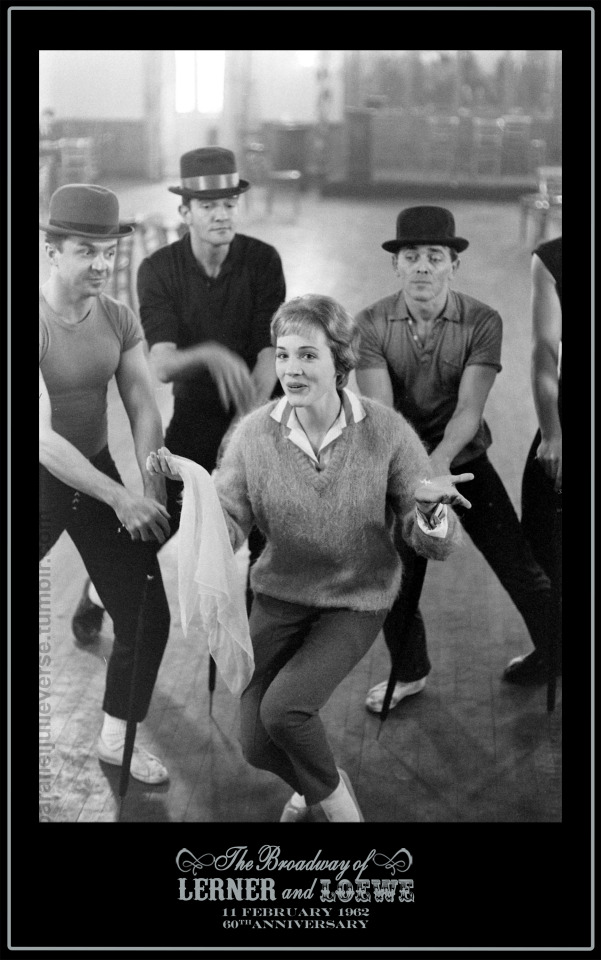

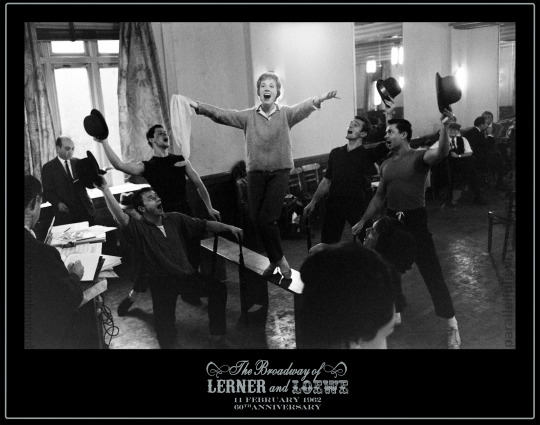

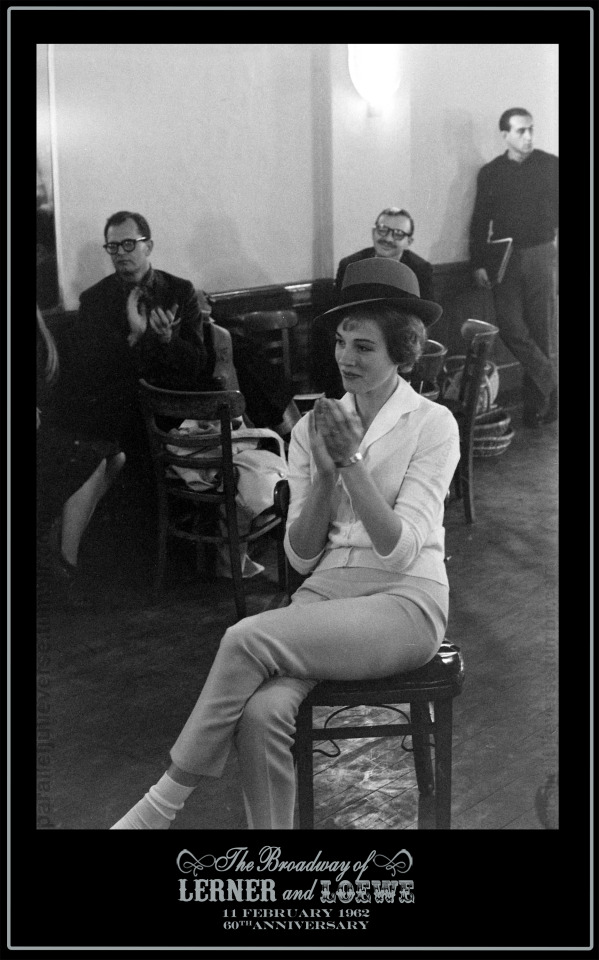

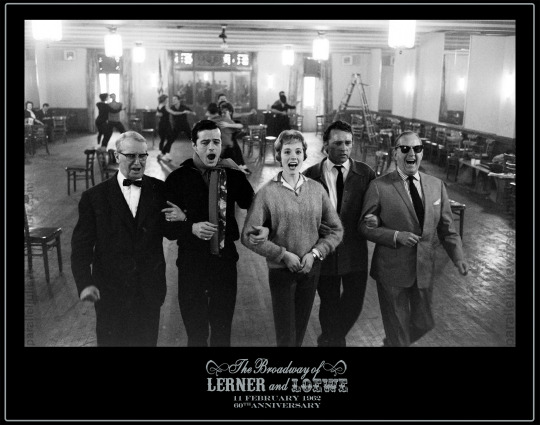

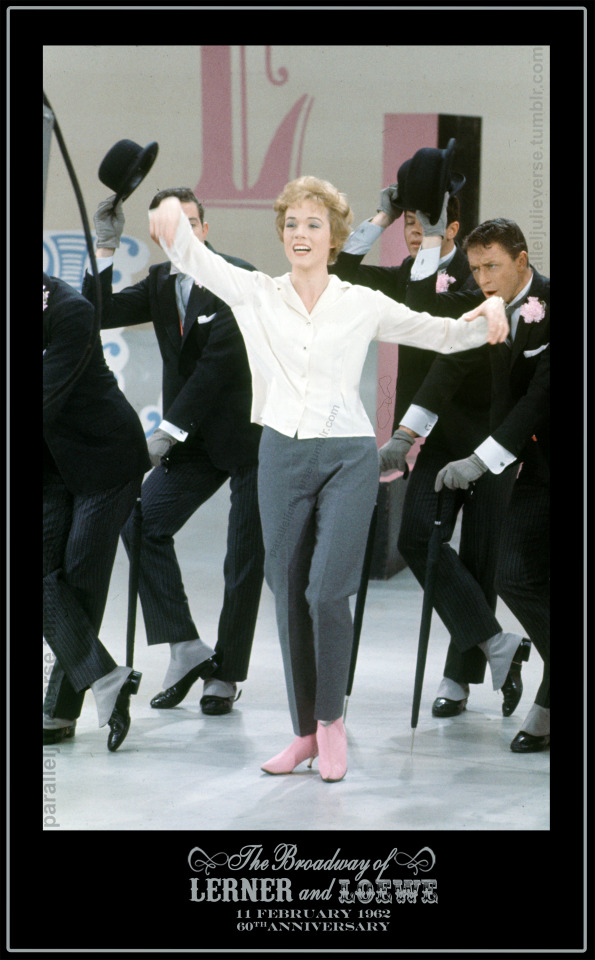

The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe: Leonard McCombe for LIFE magazine, December 1961

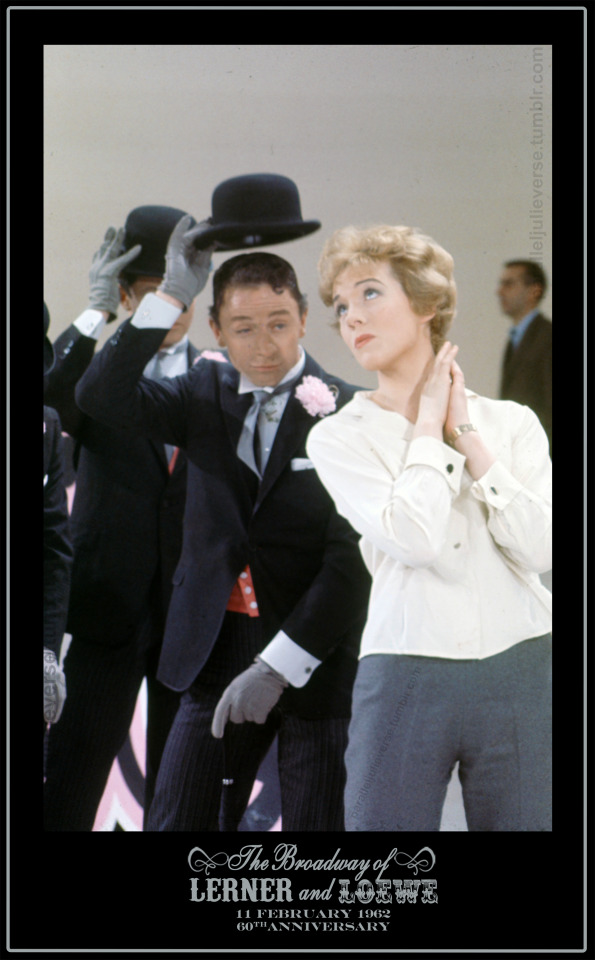

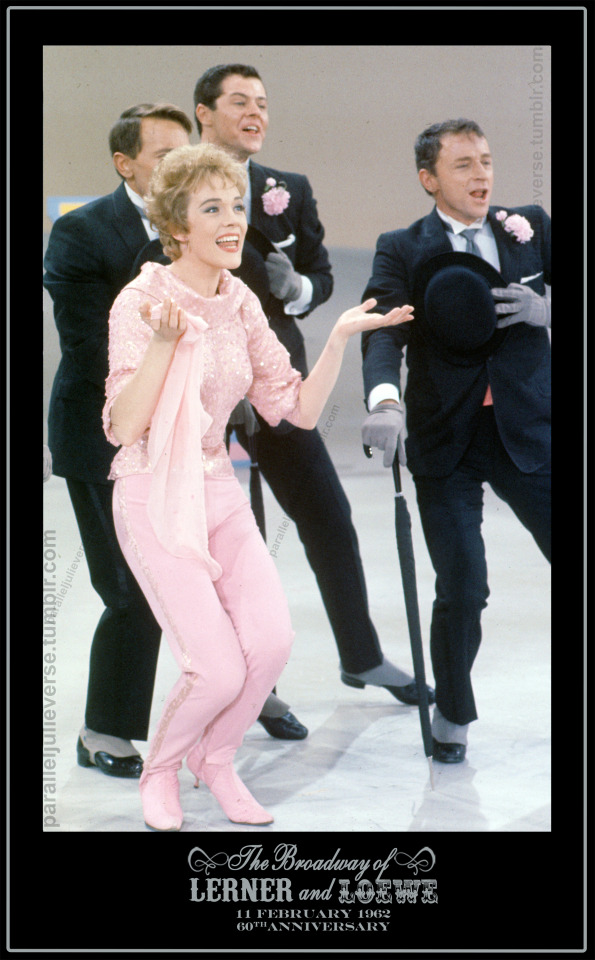

As a follow-up to our last post marking the 60th anniversary of The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe, here we profile a selection of rehearsal photos from the show that were taken by Leonard McCombe for LIFE magazine.

McCombe was one of the most celebrated photojournalists of the twentieth-century. Born in 1923 on the Isle of Man, he first took up photography in his adolescence at the recommendation of a teacher and he quickly proved a gifted artist with the camera. By age 16, he was selling his work to newspapers, and, by 21, he was the youngest person ever to be admitted as a Fellow of Royal Photographic Society (Neuberg 50).

Working in the ‘available light’ tradition, McCombe became known for his candid work and his knack for ‘seizing the moment in which people are at their most revelatory’ (Loengard 88). He would always carry a camera with him and use it to ‘record his impressions and intimate reactions as naturally as another man does in his diary’ (McCombe 93).

Throughout the war, McCombe worked as a staff reporter for Picture Post in London where he documented wartime life for service personnel and homefront families alike. Following VE Day, the young photographer was sent on assignment to the Continent where his searing images of German and Polish refugees earned widespread international acclaim. They even caught the eye of Henry Luce, the famed US publishing baron, who offered McCombe a position on the editorial staff of LIFE magazine in New York. Emigrating Stateside, McCombe would remain with LIFE for over 25 years till the magazine’s close in 1972 (Loengard 88).

A veritable cultural institution of mid-century America, LIFE was famous for its ‘pictorial essays’ chronicling American life across political, professional, entertainment, and personal spheres. Early photographic essays in the magazine were mostly ‘preconceived by editors and scripted in advance’ (Chapnick 30). McCombe’s work brought a spontaneity and immediacy that shifted the magazine’s photographic house style. He quickly established a high profile in American photojournalism. In 1950, at age 27, he was named ‘News Photographer of the Year’ and he took out the same prize five years later, becoming the only photographer to win twice (Time Inc 1950 and 1955).

Most of McCombe’s work for LIFE focussed on ordinary Americans. His two most celebrated photo-essays, for example, documented a day in the life of an aspiring 1950s Madison Avenue ‘working girl’ and the twilight culture of American cowboys in the Texas panhandle (Loengard 1998). However, given the enormous significance of celebrity to American culture and, by extension, American publishing, he was inevitably called upon to shoot well-known subjects as well: ranging from US presidents to Hollywood stars. In keeping with his personal style, McCombe eschewed the staged formalism typically used in celebrity portraiture for a more improvised approach: ‘being with the subject and capturing the off-guard moments in a real person’s life’ (Chapnick 31).

These behind-the-scenes shots from The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe are a good case-in-point. Taken for a multi-page spread in the 5 January issue of LIFE that was promoting ‘a pair of TV blockbusters’ from Julie and Lucille Ball, the shoot highlights the stars in rehearsals – ‘working up routines’ and ‘giving out [with] high spirits’ – rather than the polished end product (Thompson 75). Through McCombe’s fly-on-the-wall lens, we see the grinding labour of stardom as the performers practise numbers and work on their choreography. We also see them in unguarded moments, taking a break, conversing between sessions, collapsing with fatigue. It is an engagingly documentary approach that is very different to standard views of mid-century celebrity culture.

It was not the first time McCombe shot Julie. He took the photos – including the famous cover image – that accompanied Julie’s first star spread in the 26 March 1956 issue of LIFE when she was appearing in My Fair Lady. He also shot her at various social events in New York over the years, including the 1959 party Jack Benny threw in her honour and again at the opening night party for Sammy Davis Jr’s Golden Boy at Sardi’s in October 1964. In all these examples, McCombe brought a characteristic freshness and off-the-cuff candour that continues to captivate more than half-a-century later.

Sources:

Chapnick H (1994) Truth needs no ally: Inside photojournalism. University of Missouri Press, Columbia MO.

Loengard J ed. (1998) LIFE photographers: what they saw. Bullfinch Press, Boston, Mass.

McCombe L (1953) I become a citizen: LIFE’s cameraman tells how he took new home. LIFE. 17 August: 93-101.

Neuberg H (1952) Leonard McCombe. Camera: Internationale Monatsschrift für Photographie und Film. No. 31: 47-50.

Thompson EK (1962) Spotlight: A lusty return by Lucy, a tuneful romp for Julie: two queen prepare for TV shows. Life. 52(1) 5 January: 74-79.

Time Inc (1950) Speaking of pictures…: LIFE’s Leonard McCombe is picked as “news photographer of the year”. LIFE. 28(15) 10 April : 12-15.

Time Inc (1955) Speaking of pictures…: Winning group, these four photos helped LIFE men get top prizes. LIFE. 28(15) 10 April : 12-14.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2022

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

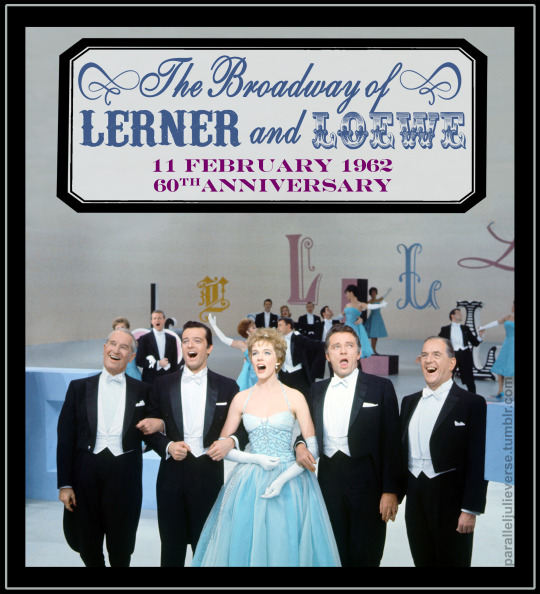

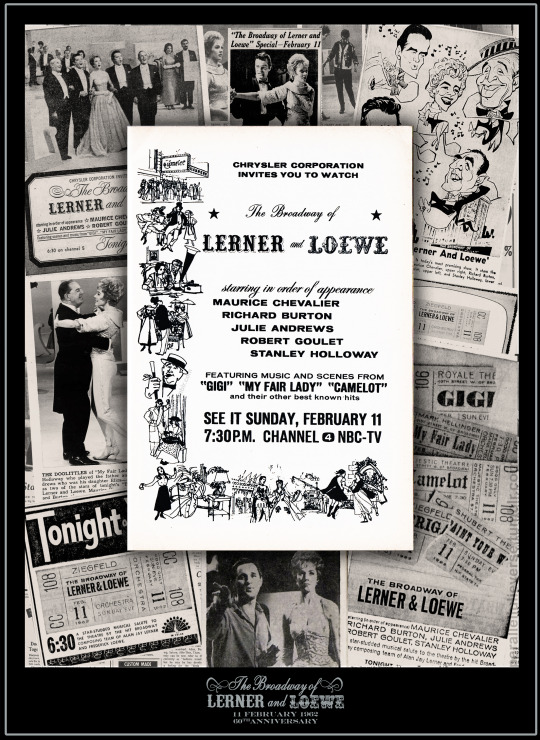

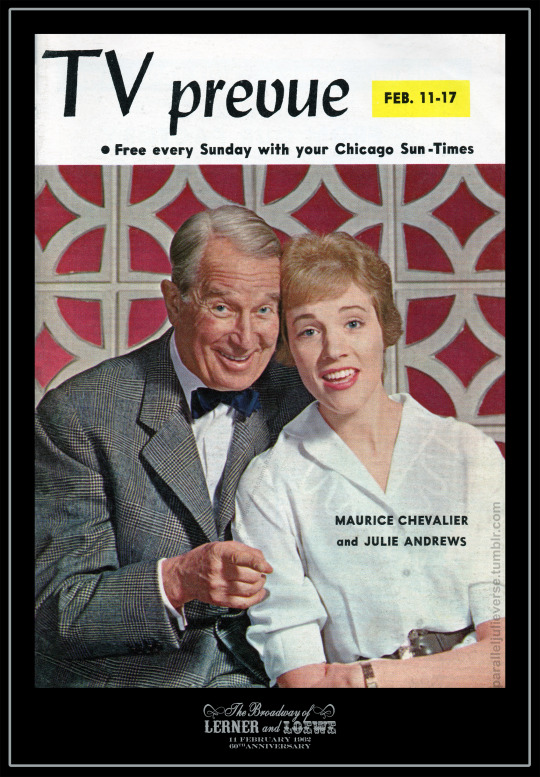

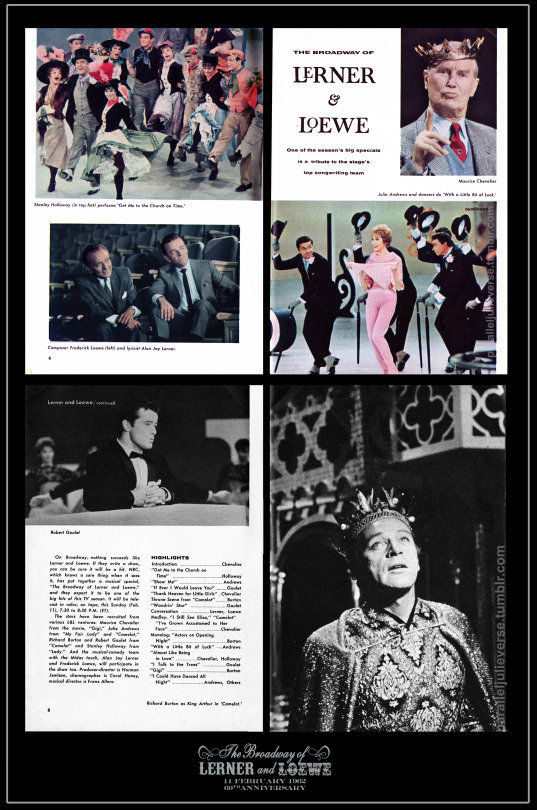

This Week in Julie-history: The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe airs on NBC, 11 February 1962

1962 was a year of significant changes in the life and career of Julie Andrews. It was the year she gave birth to her daughter and became a parent for the first time, something she frequently cites as her ‘greatest achievement’ (Andrews, 254). It was the year she bowed out from Broadway and took leave for what would prove to be a three-decade hiatus (Downing 8). And it was the year she was signed by Walt Disney for Mary Poppins and the start of a meteoric film career (Skolsky, 8).

1962 was also an important year for Julie Andrews on television (Hull 1962). She was certainly no stranger to the small screen, having appeared in numerous variety shows, as well two gala tele-musicals, High Tor (1956) and Cinderella (1957). But in 1962 Julie appeared in a pair of TV spectaculars that showcased her versatility like never before. Most memorably, in June of that year, she co-starred with chum Carol Burnett in Julie and Carol at Carnegie Hall, a concept special that emerged out of the pair’s charismatic teaming on The Garry Moore Show. It proved a landmark event with ‘audience[s] clamor[ing] for more [and] critics dust[ing] off their most glowing verbal bouquets’ (Julie & Carol 7). The Julie and Carol show proved so popular that it launched a multi-decade series of reunion specials.

While it was inevitably eclipsed by the success of the Carnegie Hall special, there was another earlier TV gala that showcased the manifold talents of Julie Andrews for the TV-viewing public of 1962: The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe. As its name would suggest, the show was a tribute to the famed composer-lyricist team and their most popular musicals of the preceding fifteen years: Brigadoon, Paint Your Wagon, My Fair Lady, Gigi, and Camelot. It was also a showcase for some of Lerner and Loewe’s greatest star performers who had been given ‘an opportunity to shine at his (or her) best’ in their shows: namely, in order of appearance, Maurice Chevalier, Richard Burton, Julie Andrews, Robert Goulet, and Stanley Holloway (Color special 9-F).

That Julie was the (only) leading lady in the line-up was as fitting as it was complimentary. Not only was she was the star of two of Lerner and Loewe’s biggest Broadway hits, My Fair Lady and Camelot, but her marathon runs in these shows meant that, as Lerner himself noted, ‘Julie has been playing for us nearly one fifth of her life!’ (Downing 8).

There was added contextual significance to putting Julie firmly in the limelight in The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe. Jack Warner had only just secured the film rights for My Fair Lady and casting for the film version was the hottest topic in town (Archer 1). It is now a matter of historical record that Audrey Hepburn was Warner’s first – and, as it transpired, only– pick for the plum role of Eliza, but press reports at the time suggested Julie was still in potential consideration (Scott 6). Certainly, Julie held out hope. Not long after the decision was made to go with Hepburn, Julie related in interview:

‘[N]aturally I thought about myself for the movie role. But although I’m an optimist, and secretly hoped it would be I, I knew that I was a second or third choice. There were three of us in the race – Audrey, Shirley Jones and myself. And if they didn’t get Audrey, I felt I had a chance. I know the part so well, and I did think it would be fun taking a crack at it again’ (Shearer 7).

As such, there was a lot riding on The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe and the special worked to showcase Julie to strong effect: giving her an opportunity to sing, dance, and emote in a series of both solo and ensemble set pieces including the explosive ‘Show Me’ from My Fair Lady. In addition, publicity for The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe played up the angle of Julie as star with profiles in major publications including a pictorial spread in Life magazine that twinned Julie with Lucille Ball as dual ‘queens’ of TV (Thompson 1962).

The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe was conceived and developed by Norman Rosemont, executive vice president and general manager of the Lerner-Loewe organisation. He spent almost three years pre-planning the project and securing a very lavish production budget of $350,000 (Bryant 3-D). To helm the production, Rosemont brought on board the talented young Canadian director, Norman Jewison. Today Jewison is best remembered as the award-winning film director of major Hollywood hits such as In the Heat of the Night (1967), Fiddler on the Roof (1971) and Moonstruck (1987), but the versatile director cut his professional teeth in TV. During the 50s and early-60s, Jewison helmed a series of big variety specials for major stars of the era including Harry Belafonte, Danny Kaye, Andy Williams and Judy Garland that saw him become ‘the highest-priced director of the highest-priced musical variety shows in all television’ (Krantz 21). Jewison had previously worked with Julie on The Fabulous Fifties (1960) and the pair had a very sympathetic professional and personal relationship (Stern 10).

A true creative, Jewison felt that a TV ‘show should have something to say…there must be a reason for a show to be on the air’. In the Lerner and Loewe special, Jewison described his approach as wanting to ‘take a look at the modern American musical theatre’:

‘It’s a magical thing, the stage. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, but it’s magic. On the show we’re letting several of our stars do numbers they’re not associated with, even though they were in the shows the numbers came from’ (Stern 10)

To this end, Jewison included several surprise twists such as Julie doing a jazz version of ‘A Little Bit of Luck’, Chevalier singing a jaunty ‘Camelot’, Burton performing the title song from Gigi, and Chevalier and Holloway singing a music-hall duet of ‘Almost Like Being in Love’ from Brigadoon. Jewison also included several big set pieces from these shows such as the throne room scene from Camelot and a grand ensemble finale of ‘I Could Have Danced All Night’ (Gaver 1962a 12).

Helping Jewison and his stars bring the production to life was a support team of major theatrical and TV talent (Messina 50). The show’s musical director and conductor was Franz Allers who had performed similar musical duties for most of Lerner and Loewe’s Broadway shows. The choreography was by Carol Haney, longtime associate of Gene Kelly in Hollywood and a major Broadway choreographer in her own right. To supplement the star power in front of the camera, memorable cameos were provided by Charles Nelson Reilly and Frances Sternhagen in a comic sketch interlude (Bryant 3-D).

The show itself was pre-taped at NBC’s New York studios in December 1961 (Ashby 1). Organising the production around the performers’ busy schedules was a major logistical challenge. Burton had to fly in from Rome where he was filming Cleopatra, Chevalier jetted in from the London set of Disney’s In Search of the Castaways, and Stanley Holloway came from taping a TV pilot in Los Angeles (Hull 5). Julie and Goulet were both still appearing in Camelot, so filming had to fit around their theatre commitments. In interview at the time, Julie described the taping of the show as ‘utterly crazy’:

‘We rehearsed for three weeks. They started taping about 7a.m. on a Saturday and finished Monday night about 6. And I had to break away for two Broadway shows on Saturday, and I was back taping at 8 a.m. Sunday and worked till 11 p.m., and the same arrival Monday and I finished at 2 p.m. and then to the theatre for the show on Monday night. Tuesday? I collapsed’ (Quigg 6E).

A full-colour broadcast of The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe was scheduled by NBC for Sunday 11 February from 7:30-8:30p.m. – a primetime slot usually occupied by Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (Ashby 1). With sponsorship from Chrysler, it was given ‘one of the biggest publicity campaigns of the year’ (Smith 1962a C-12). The broadcast proved a major winner for both the network and the sponsor, attracting ‘big ratings’ and a favourable ‘letter response’ (Gaver 1962b 3).

Critical reception of the show was equally positive. There were a few dissenting voices – the critic for The New York Times felt ‘the cumbersome injection of static commercials and other episodic intrusions’ meant that ‘the lilt and captivation of Broadway were realised only sparingly’ (Gould 36) – but, for the most part, reviews were little short of laudatory:

Los Angeles Times: ‘[A] buoyant, bouncing, glittering color extravangaza…the show as a whole was a most pleasant hour…The soaring voices of Robert Goulet and Julie Andrews gave wings to the show [and] Norman Jewison staged the action with imagination’ (Smith 1962b C-12).

Chicago Tribune: ‘Rarely were so many performers of great musical and dramatic gifts assembled for television and never have they performed with more enchantment…Last night, TV was a musical paradise, an Eden of color and shining melody…Chevalier, at 73, gave a great performance as the host, and as a singer and dancer, Julie Andrews was in fine fettle’ (Wolters F-7).

Boston Globe: ‘It was a stirring, glittering presentation that in an hour caught much of the essence and magic of the Lerner-Loewe life “book”….It was a show to be treasured throughout…with Holloway tripping so delightfully through the rhythms of “Get Me to the Church on Time”, the adorable Miss Andrews taking her frustration out on dancer Johnny Harmon so prettily in “Show Me”, and Burton reciting his throne speech from “Camelot” so affectingly’ (Shain 12).

The Herald-Journal: ‘A more tuneful, professional folic through the wonderful song world of one of history’s most successful collaborations would be hard to imagine…Miss Andrews was never better on TV. She looked radiant’ (Danzig 8).

Daily Herald: ‘Take the product of song-writing team which has churned out such shows as “My Fair Lady”, “Gigi” and “Brigadoon”. Cast their finest moments with talent like Julie Andrews and Maurice Chevalier. Let a director of taste and imagination pull it all together. The result is a joy and a delight…Altogether it was a bright, warm and beautiful show’ (Lowry 8).

Cincinatti Enquirer: ‘[I] was almost overwhelmed by The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe…one of the gayest, most beautiful shows of the season. Staging and production of this song-fest of five fine Lerner-Loewe shows was most impressive. It was as colorful as the NBC peacock–in fact it was probably the best TV colorcast I’ve ever seen’ (Feck 10)

Valley Times: ‘Last night’s special production of The Broadway of Lerner of Loewe on NBC was unquestionably one of the highlights of the season and constituted a shining example of television production at its very best…Miss Andrews was never better, and that sentimental favourite, Chevalier, perfectly complemented the younger male stars of the cast…Add beautiful sets, superb production, lavish costumes and the overall director of Norman Jewison and you come up with a package that simply exudes class’ (Rich 9).

Detroit Free Press: ‘At least once a TV season amid the mountains of mediocrity, there appears one shining peak, a show to be treasured. Sunday’s The Broadway and Lerner and Loewe on NBC-TV, was one of those: an hour to rank…among TV’s greatest programs’ (Peterson 22).

Happily, because The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe was taped, it remains in existence and archival quality copies are stored in several repositories including the NBCUniversal Archives and the Paley Center for Media. The programme has never been given an official video release and, with copyright constraints, likely never will. However, multiple-generation fan copies of the show have circulated for years and can even be viewed on YouTube. Though not the greatest quality, it gives a sense of the colourful musical magic that TV audiences were treated to sixty years ago this week in The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe.

Sources

Andrews J (2008) Proust questionnaire. Vanity Fair. 572, April : 254.

Archer E (1961) 5 million film offer made for ‘Fair Lady’. New York Times, 27 September 27: 1, 78-79.

Ashby B (1961) Five top stars in February’s NBC ‘Broadway of Lerner and Loewe’. The Herald-Mail Video Viewer, 2-8 December: 1.

Bryant J (1962) ‘Lerner & Loewe’ extra-special. ShowTime. 9 February: 3-D.

Color special to be salute to Broadway (1963) The Shreveport Times. 11 February: 9-F.

Danzig F (1962) TV in review. The Herald-Journal. 12 February: 8.

Delatiner B (1962) Songs by Lerner and Loewe- ’nough said. Newsday. 12 February: C-2.

Downing R (1962) Cast honors M’el Dowd, Julie Andrews. The Cedar Rapids Gazette. 17 April: 8.

Feck L (1962) TV and radio: Weekend watching. The Cincinatti Enquirer. 13 February: 10.

Gaver J (1962a) Norman Jewison produces imaginative specials. TV Week. 28 January-3 February: 12.

_______ (1962b) The fall TV ‘special’ lineup is still up in the air waves. Oakland-Tribune TV and Radio. 10 June: 3.

Glenn NR (1962) This is NBC. Sponsor. 2 April: 16-17.

Gould J (1962) TV: ‘Broadway of Lerner and Loewe’. The New York Times. 12 February:

Gross B (1962) Lerner & Loewe lead us down a magical street. Daily News. 12 February: 41.

Hull B (1962) Julie Andrews finds time for TV: Broadway star in Lerner and Loewe special tonight. Los Angeles Herald-Examiner TV Week, 11-17 February: 4-5, 12.

Krantz, J (1963) Norman Jewison: the stars’ status symbol. MacLeans. 76(1) 5 January: 20-21, 30-32.

Lass B (1962) Starring Julie Andrews. The Courier-Journal Magazine: 36-37.

Julie & Carol renew magic with Carnegie Hall smasher (1963) TeleVues, 9-16 June: 7.

Lowry C (1962) ‘Radio/TV: “Broadway of Lerner and Loewe” good show’. The Daily Herald. 12 February: 8.

Messina M (1961) Stars set for musical spec. Daily News. 27 November: 50.

Peterson B (1962) Lerner and Loewe special: show to rank with TV’s great. Detroit Free Press. 13 February: 22.

Quigg D (1962) TV, Broadway and interviews keep Julie hopping. Chicago Tribune. 11 February: 4.

Rich, A (1962) Chrysler special called smash hit. Valley Times. 12 February: 9.

Rose. (1962) Television reviews: ‘The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe’. Variety. 14 February: 36.

Royal D (1962) Extremes meet at Carnegie Hall: Julie, Carol. Ithaca Journal: Showtime. 9-15 June: A5.

Scott V (1962) Big question in Hollywood: who will be ‘My Fair Lady’? The Herald-Journal. 19 April: 10.

Shain P (1962) Night watch: Lerner-Loewe showpiece – need you say more? The Boston Globe. 12 February: 12

Shearer L (1963) Julie Andrews, Audrey Hepburn: Is there a five-million dollar difference between these two girls? Parade: The Sunday Newspaper Magazine. 4 August: 6-7.

Skolsky S (1962) Hollywood: Gossipel truth. Los Angeles Evening Citizen. 19 June: 8.

Smith C (1962a) The TV scene: Jewison makes Lerner-Loewe go. Los Angeles Times. 9 February: D-12.

_______ (1962b) The TV scene: Rare kudos for a rare sponsor. Los Angeles Times. 12 February: C-12.

Stern, H (1962) Norman Jewison directs 2 star-studded TV specials. News-Journal Weekend Magazine, 4 February: 10.

Thompson EK (1962) Spotlight: A lusty return by Lucy, a tuneful romp for Julie: two queen prepare for TV shows. Life. 52(1) 5 January: 74-79.

Wolters L (1962) Theater a madness and critic is happy. Chicago Tribune. 12 February: F-7.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2022

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

70th anniversary of Aladdin London Casino, 103 performances with 1 charity preview (19 December 1951 - 23 February 1952)

This week marks the 70th anniversary of another milestone event in the early career of Julie Andrews: the opening of Aladdin at the London Casino on 19 December 1951.

Aladdin was Julie’s third annual pantomime, following earlier runs in Humpty Dumpty (1948) and Red Riding Hood (1950). By Christmas 1951, Julie was 16-years-old and an established young star of variety and radio. She was thus ‘promoted’ in Aladdin to the ‘principal girl’ role of Princess Balroulbadour — her first adult part — and given top billing alongside the show’s other principals, Jean Carson and Nat Jackley (Bishop, p. 6; ’Principal’, p. 5).

Aladdin also marked the second Christmas show Julie did with Emile Littler, the celebrated theatre impresario who, as discussed in an earlier post, was a formative figure in the star’s early career. Popularly dubbed the ‘King of Pantomimes’ – a soubriquet which was, admittedly, shared by a few other theatre magnates – Littler was famous for his legendary Christmas extravaganzas. In any given year, Littler would produce upwards of half-a-dozen pantos across the nationwide theatre chain he ran with brother, Prince, and sister, Blanche (Pedrick, p. 8).

A producer of the old school, Littler took an active role in these shows, not only producing but also writing, casting, and, in many cases, directing them himself (Pedrick, p. 8). Such was his commitment to pantos that Littler established a dedicated production facility in Birmingham, ‘Pantomime House’, where a team of craftsmen and women worked year-round to prepare the costumes, scenery and props needed for the lavish shows (Konig 1949). “No man,” opined one contemporary commentator, “has ever carried on such a wholesale enterprise for the production of Pantomime” (Wilson, p. 127).

For the Christmas season of 1951, Littler launched an ambitious roster of eight pantos across the country: alongside Aladdin at the London Casino, there was Little Miss Muffett at the Manchester Hippodrome; Puss in Boots at the Leeds Empire; Mother Goose at the Birmingham Royal; Humpty Dumpty at the Sheffield Empire; Jack and Jill at the Plymouth Palace; Cinderella at the Hanley Royal; and, Goody Two Shoes at the Bournemouth Pavilion (’Emile Littler Sends’, p. 5)

The biggest and most prestigious Littler panto was, not surprisingly, the London offering. Commencing in 1941, Littler staged a major West End panto each Christmas, initially at various theatres but, from 1946, moving permanently into the recently refurbished London Casino which Littler co-owned with Tom Arnold (Emile Littler Souvenir, p. 25; Knox, p. 314). Aladdin would be Littler’s eleventh London pantomime and his seventh at the Casino.

The show was based on a script treatment of Aladdin that Littler had developed for earlier productions. In keeping with panto traditions, the story is set in China, rather than the Middle Eastern locales popularised though later Hollywood versions of the tale (Chang, pp. 180-192). Aladdin is a carefree lad who lives in “Old Peking” with his mother, the laundress Widow Twankey, and his spoiled younger brother, Wishee Washee. Aladdin meets and falls in love with Princess Balroulbadour, much to the displeasure of her father, the Emperor, who charges his bumbling policemen to keep the impish lad away. Meanwhile, a mysterious stranger, Abanazar, has appeared claiming to be a long lost relative of Widow Twankey. He coaxes Aladdin to accompany him to a cave in the mountains so that he may retrieve a magical lamp. Aladdin finds the lamp but refuses to give it to Abanazar as promised. Cursed and imprisoned by Abanazar in the cave, Aladdin rubs the lamp, conjuring the magical genie, Kazim, who grants Aladdin his wish to become a wealthy Prince and thus clear the way for him to marry the Princess. Abanazar returns to create more mischief, stealing the lamp and using its power to transport the Princess and the entire Palace to Egypt. In possession of a magic ring, Aladdin summons the Fairy Queen who takes the lad to Egypt in pursuit where he thwarts Abanazar, wins back the Princess, and brings proceedings to a happy ending.

As is often the case with panto, the story of Aladdin is something of a pretext for the genre’s main points of appeal: spectacle, stars, music, comedy, and audience participation. With his 1951 staging of Aladdin, Little was determined to up the ante on all counts. Afforded a huge production budget of over £50,000, it was Littler’s most expensive panto to date and he pulled out all the stops with lavish production values, state-of-the-art stagecraft, and top-notch talent (Lloyd-Williams, p. 4; Wearing 2014, p. 138).

For the costume and scenery, Littler contracted Anthony Holland, a young set designer with a flair for visual spectacle (Hainaux 1965). The show’s Eastern settings were a perfect fit for Holland’s aesthetic and he went to town designing over a thousand costumes at a cost of £15,000 (Lloyd-Williams, p. 4). The sumptuous costumes were recalled fondly by Julie (2008) in the first volume of her memoirs: “I wore exotic, sparkling headdresses, which I loved, and a lot of satin kimono-style robes with long, draped arms” (p. 140). In addition, Holland designed fifteen changing sets for Aladdin complete with revolving buildings, a garden with a huge tree made of jade clouds, and a gasp-inducing cave of magical wonders. The result was what The Times described as “a breathless succession of marvels” (‘London Casino’, p. 6).

For the music, the show featured a mix of classic tunes interspersed with original compositions by Littler’s resident house composer, Hastings Mann (‘Hastings Mann’, p, 3). Overseeing the musical arrangement and direction for the production was Debroy Somers, the celebrated big band leader and star conductor (‘Debroy’ p. 3). Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado had just come out of copyright, and the musical team drew heavily from the score, interpolating several songs – in one scene, the chorus sang ‘Gay Little Mandarins Are We’ to the tune of ‘Three Little Maids’ – and using other musical motifs and bridges as entrance music (‘Christmas Shows’, p. 5).

The cherry on top of this spectacular theatrical and musical confection was the cast. Announced in October 1951, the cast for Aladdin was a star-studded line-up of big names from theatre, variety, film, dance, circus, and, even, opera. Other than Julie, the show’s featured performers included:

Jean Carson as Aladdin (principal boy): A vivacious flame-haired Yorkshire lass with a strong voice, comely appearance, and good comic flair, Carson started performing from a young age as part of her parents’ music hall act and she quickly emerged as a favourite on the variety and musical theatre circuit. In 1948, aged 20, she had an early success in Starlight Roof, the celebrated Val Parnell revue show at the London Hippodrome that also launched 12-year-old Julie Andrews to stardom. The same year Carson scored her first film role with a lead in the British musical revue, Date with a Dream (1948). Something of an Emile Littler protege, Carson appeared in several of his productions including a string of Christmas pantos where she typically took the part of the principal boy. She played the role of Aladdin in a 1948/49 Littler production at the Sheffield Empire which is possibly why she was tapped to recreate the role in the bigger London staging three years later ( ‘Provincial Pantomimes’, p. 8). Littler would also give Carson her greatest stage triumph when he cast her as the lead in the Hugh Martin scored musical, Love from Judy, a role she would play to great acclaim on the West End and elsewhere from 1951-1953. A film contract with Rank ensued where Carson starred in light musical comedies such as As Long As They’re Happy (1954) and An Alligator Named Daisy (1955). At the height of her British success, Carson was coaxed to the United States by a record-making TV deal where she was rechristened Jeannie – to avoid confusion with the American TV star, Jean Carson of Peter Gunn and The Andy Griffith Show fame (‘Jean Carson makes’, p. 11). Carson’s US career got off to a promising start. She appeared in a number of well-received TV specials before being launched as the star of her own CBS TV sitcom, Hey, Jeannie! (1955). Sadly, the series failed to ignite and it was cancelled after just one season (Tucker, pp. 54-60). Thereafter, mainstream US success eluded Carson, though she continued to find work in musical theatre. She starred in a 1960 Broadway revival of Finian’s Rainbow, where she met the man who would become her American husband, actor Biff McGuire. The pair worked frequently together, including starring in a touring production of Camelot in 1964 (Waters, p. 3). In the 1970s, the couple settled in the Seattle area where they become stalwarts of the local theatre scene for almost fifty years till McGuire’s recent passing in early-2021 (Seattle Rep 2021). As of the time of writing, Miss Carson is living in retirement in Seattle at the grand old age of 93. She has often been asked over the years about her memories of working with Julie and her standard reply is to boast with a smile that “I was Julie’s leading man!” (Holloway, p. A-7).

Nat Jackley as Widow Twankey (Panto Dame): Lanky and loose-limbed, Nat Jackley was a visual comic who found enormous success on the British music hall scene. Born into a show business family, Jackley started in his teens with the famous clog-dancing Eight Lancashire Lads, the same troupe that gave an early start to Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel (Dixon, p. 39). Jackley migrated into a series of comedy duos, first with his sister Joy and then with fellow comedian Jack Clifford, before going solo during the war. Billed as Nat ‘Rubber Neck’ Jackley, he developed a trademark blend of eccentric dancing, jerking neck movements, and an original funny walk described by one critic as “the strut of a demented turkey” (’Nat Jackley’, p. 35). At the height of his career, he topped the bill at the Palladium, appeared in three Royal Variety Performances, and made a successful tour of Australia. He also featured in a string of popular British films such as Demobbed (1944), Under New Management (1946), and Stars in Your Eyes (1956). With the demise of variety, Jackley moved into television and had a successful late career as a character actor in a diverse range of British TV shows. Another string to Jackley’s professional bow was as a legendary panto Dame and he appeared in a record fifty pantos between 1927 and his retirement in 1980 (ibid.). In Aladdin, he took on one of the most famous of all Dame roles, Widow Twankey, Aladdin’s comic-vain mother. Jackley passed in 1988, aged 79.

Walter Crisham as Abanazar: Though he is little remembered today, Crisham was a noted American actor of stage and screen who appeared in number of high profile productions. Born in Worcester, Mass. in 1908, he originally trained as a dancer and performed in several musical revues in the New York area during the 1920s. In 1933, Crisham travelled to London to appear in a dance revue called Ballyhoo and he ended up staying in the UK for almost twenty years (Short, pp. 88-89). Some of his more notable British stage successes included Cole Porter’s Nymph Errant (1933), opposite Gertrude Lawrence; the Ivor Novello musicals, Careless Rapture (1936) and Crest of the Wave (1937); several revues with favourite partner, Hermione Gingold, including Rise Above It (1941), Sweet and Low (1943) and Slings and Arrows (1948); and, Don’t Listen Ladies (1949) opposite Jessie Matthews. Throughout this period, Crisham made a number of films including several straight dramas such as They Met in the Dark (1943), No Orchids for Miss Blandish (1948) and Her Favourite Husband (1950). He scored his most famous film role in the small but flashy part of Valentin le Désossé in John Huston’s Moulin Rouge (1952). Though he had appeared in a West End holiday production of The Wizard of Oz in 1946, Aladdin would be Crisham’s first and only panto with one critic noting that “he makes his debut in pantomime with a zest implying that such has been his ambition all along” (Dent, p. 3). Crisham returned to the US permanently in the late-1950s, settling in the Los Angeles area. Other than a few minor TV appearances and some community theatre work, he seems to have entered semi-retirement. He passed in 1985 (‘Walter’, p. 54).

Martin Lawrence as The Emperor: A distinguished operatic bass who had forged a garlanded career in the opera houses of Europe, Lawrence was an unorthodox choice for a Christmas panto – and, indeed, much was made in the press about his “history making” casting (’Concert Notes’, p. 6). His stature and booming voice was, however, a good fit for the magisterial role of the Emperor and, well versed in the comic traditions of opera buffa and Gilbert and Sullivan, Lawrence had “an ease in humorous acting” that meant “the transition from grave to gay in no way daunts him” (ibid.). Alongside his career in opera where, among other achievements, he created the role of Don Jerome in Gerhard’s The Duenna, Lawrence was a strong proponent of traditional Jewish music. He made several recordings of Yiddish folk songs, wrote a number of studies on the history of Jewish music, and was, for many years, the musical director and choirmaster at the New London Synagogue till his death in 1983 at 73 years of age (‘Obituary’, p. 378).

Desmond and Marks as Bend Hi and Bend Lo: Fred Desmond and Jack Marks were dancers who met in the RAF during the war and, following ‘demob’, they decided to form a comedy duo that lasted for decades (E.M.M., p. 2). With a 'knockabout’ comic act blending dance, pratfalls, and gags, ‘Desmond and Marks’ were a popular duo on the post-war variety circuit, extending to several international tours of Europe and the US (’Variety News’, p. 3; ‘Light Entertainment’, p. 3). Like many variety acts of the era, they also found regular work in pantomimes, playing comic relief support characters and, even on occasion, ‘skin’ roles including a fire-and-smoke-belching alligator (Frow, p. 179). In Aladdin , the pair performed the role of the classic – if dubiously stereotyped – Chinese policemen, Bend Hi and Bend Lo. Desmond and Marks performed in many other Littler pantos and could still be found doing Christmas shows into the 1980s (‘Christmas Greetings’, p. 40.).

Jimmy Clitheroe as Wishee Washee: A pint-sized comic actor who would find lasting fame on radio, Jimmy Clitheroe was one of the last of the popular tradition of music hall ‘midgets’. With his diminutive size, high-pitched voice, and musical Lancashire accent, Clitheroe developed a comic persona as a cheeky schoolboy with lots of sharp comments and double entrendres. In pantomimes, he would invariably play classic juvenile roles like Buttons, Tom Thumb, or, as here, Wishee Washee, Aladdin’s spoiled impish brother. Later in the decade, Clitheroe starred in his own hugely successful BBC radio series, The Clitheroe Kid that ran for 17 seasons till 1972 and spawned a parallel TV version in the 1960s (Elmes, pp. 203-7). Despite his success, Clitheroe remained his whole life in the family home, living with his mother. When his mother passed away in 1973, Clitheroe was inconsolable and, tragically, he was found dead from a suspected accidental overdose on the day of his mother’s funeral (Johnson, p. 12).

Carole Jeffries as Prince Pekoe: A 21-year-old beauty, Jeffries was a relative newcomer in the Aladdin cast. A trained dancer, she got an initial break as one of the burlesque troupe of ‘Windmill Girls’ at London’s Windmill Theatre (Storey, pp. 4-5). With ambitions for a career in musical theatre, Jeffries appeared in a few revues and provincial pantos, and even scored an early TV appearance (’She Gets’, p. 5). She had a small part in Littler’s 1950 panto at the Casino, Goody Two Shoes, and she must have impressed because he promoted her in Aladdin to the support pants role of Prince Pekoe. The following Christmas, she was promoted even further to principal girl in Dick Whittington at the Nottingham Theatre Royal. Thereafter, the available record on Jeffries grows dim. Reports state that she got married in 1953 (Stevenson 1953: p. 4), so she might have retired and/or changed her name.

David Davenport as Kazim: A versatile performer of many talents, Davenport had a distinguished career across dance, theatre, film and television (Taylor, p. 36). He trained as a ballet dancer and performed with great success in the 1940s with several troupes including the New Russian Ballet, Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, and the new International Ballet. In the 50s he moved into musical comedy and pantomime, while retaining his interest in dance as a choreographer. He forged a successful career in film and television with credits ranging from comedies (he was in three Carry on films) to straight dramas such as The Darwin Adventure (1972). Tall and distinguished with an athletic build and a booming voice, Davenport was ideally cast in the magical genie role of Kazim, the Slave of the Lamp in Aladdin. Indeed, he would reprise the part in several later productions including a 1967 TV broadcast on ITV. Davenport passed in 1995 at the age of 74 (Taylor, p. 36).

Jacqueline St. Clere as Fairy Moonbeam: An English ballet dancer, Jacqueline St. Clere started her career in the late-40s with the London-based Metropolitan Ballet (Percival, p. 22). Aladdin marked her West End debut in the principal dance role of the Fairy Queen where she was showcased to strong effect in the show’s spectacular second act ballet. During the run of Aladdin, St. Clere married Frank Staff, the celebrated South African dancer and choreographer (‘Chit Chat’, p. 18). The following year, she was cast by Littler again as principal dancer in his 1952 Casino panto, Jack and Jill, in the role of the Fairy of the Well (‘Seven-and-a-half’, p. 3). In 1953, St. Clere accompanied her husband back to his native South Africa where she helped him establish the influential Frank Staff Ballet Studio (Rosen, p. 95). St. Clere continued to perform in several of Staff’s ballets, and branched out into teaching and costume design. She had a son with Staff but the marriage ended sometime in the late-1950s. It is not known what become of St. Clere after that, though records suggest she remained in South Africa (Rosen, p. ix).

Ross Harvey as the Aviary Keeper: One of several 'specialty’ acts integrated into Aladdin, Ross Harvey – real name: Harry Rossofsky – was an American vaudeville entertainer who found considerable success with his trained bird act. Billed as ‘Ross Harvey and his Dancing Parrot-Cuties’, the act consisted of Harvey doing soft shoe routines while the birds performed acrobatic tricks on his body and fingers in time with the music (Rasmussen, p. A14). In 1951, Harvey had a high profile run at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria which garnered a good deal of press attention. The exposure inspired Emile Littler to offer Harvey a novelty spot in Aladdin where he was billed as the Royal Aviary Keeper (‘Ross’, p. 1). His spot was very well received and Harvey would return to the UK several times for other pantos and variety tours throughout the 1950s. He retired from show business in the 1960s and retrained as a cosmetologist, before passing in 2010 at the grand age of 90 (Rasmussen, p. A14).

Fiery Jack as Oriental Road Hog: Another speciality spot in the show was provided by Fiery Jack – the stage name of Fred Zetina – a well-known British clown who plied his trade in both circuses and music halls for many decades. Born into a theatrical family of acrobats, Zetina developed a novelty act built around a comical jalopy car that would shoot flames, smoke and fall apart, hence the name ‘Fiery Jack’. In Aladdin, he appeared as a motorist in one of the set scenes allowing him to perform his automative schtick. Zetina took his final bows in 1978 at the grand age of 93 (Ashton, p. 4).

The Olanders as the Royal Tumblers: A further specialty act was provided by this troupe of young acrobats. A family of five young brothers from Denmark, the Olanders rose to prominence on the European circus scene in the 1940s before moving into the more stable and lucrative world of cabaret and variety. They undertook a successful tour of the UK in 1948, including a run at the London Palladium on a bill with Danny Kaye. They were contracted by Emile Litter to perform in his end-of-year panto, Jack and Jill at the Manchester Hippodrome where they impressed with their “exhilarating display of high speed somersaults” (M.M., p. 3). Thereafter, the Olanders became somewhat of a regular feature on the Littler panto circuit, appearing again in his 1949 staging of Jack and Jill at the Leeds Empire (A.T., p. 6) and the show’s 1950 reprise at the Coventry Hippodrome, co-produced by Littler and S.H. Newsome (’Accent’, p. 4). In 1951, the Olanders were afforded the ultimate honour of appearing in Littler’s London panto where they were billed as Royal Tumblers in the Court f the Emperor. By this stage, one of the original brothers had left the troupe and a young English adoptee was added (’Boy Acrobat’, p. 11). The Olanders have a special place in Julie lore as one of the boys, Fred, was an early crush for the 16-year-old. In her memoirs (2008) she recalls him as “attractive, fit (obviously), and very gentle and dear” (p. 140).

The Tiller Girls (Dance Chorus): This famous precision dance troupe first formed by John Tiller in the 1890s became such a popular feature of British entertainment that Tiller schools were set up all over the country and multiple troupes of trained dancers sent to theatres far and wide (Reilly 2013). Renowned for their tightly synchronised routines and disciplined kick lines, Tiller Girls provided backing for principal performers as well as showcase displays of formation dancing during spectacle scenes. The troupe of Tiller Girls used for Aladdin consisted of 32 dancers under the tutelage of Phyllis Blakston, Littler’s resident choreographer.

The Terry Children (Juvenile Chorus): Like the Tiller Girls, the Terry Children was something of a British theatrical institution of the era. Juvenile choruses, or ‘babes’ as they were often known, were a core ingredient of pantomime dating from the Victorian era and there were several companies that emerged to meet market demand for trained child performers (Varty, pp. 138-147). ‘Terry’s Juveniles’ was one of the most successful. It was established in the late-1910s by an enterprising dance instructor who went by the name of “Miss Terry", likely to cash in on the celebrated Terry theatrical dynasty. By the 1930s, Miss Terry had a plush office in Shaftesbury Avenue and several stage schools offering lessons and hopes of theatrical glory to the tiny tots and pushy stage parents of Britain (‘Baby Terry’, p. 7; ‘Terry’s Juveniles’, p. 14; ‘Terry Triumphs’, p. 11). Terry’s Juveniles was also the preferred source of panto babes for Emile Littler and he would regularly feature troupes of Terry Children dancing and singing their little hearts out in his shows. For Aladdin, Terry’s Juveniles provided a troupe of 24 ‘babes’ who coaxed collective oohs-and-aahs with their cute antics and what one critic termed “simple but effective ensembles” (Beaumont, p. 7). Though demand for its brand of hyper-trained child choruses was dwindling, Terry’s Juveniles continued into the 1960s before finally closing in 1968. Miss Terry passed in 1973 (‘Obituary’, p. 19)

With the cast in place, rehearsals for Aladdin started in mid-November at the London Casino. The Littler revue, Latin Quarter of 1951, was still playing till the end of the month so the cast performed in the rehearsal space before moving onto the stage proper in the first week of December. With a fixed holiday run of just a few months, pantos in this era didn’t usually hold previews. However, Aladdin did host a special ‘charity preview performance’ on Tuesday, 18 December, the day before its official opening, in aid of the King George’s Fund for Sailors with Lord and Lady Mountbatten in attendance (‘Events’, p. 13). Public performances of Aladdin started the following day on Wednesday 19 December.

Aladdin was the first of the big West End pantomimes to open for the 1951 season and it attracted a good deal of critical attention. For the most part, reviews were good, even glowing, with Julie singled out for her glorious singing. Below is a sample of excerpts from reviews of Aladdin in some of the major publications:

The Times: “The pantomime season opens with a flash and a bang…Mr Emile Littler’s Aladdin admirably satisfies the requirements of this strange form…It provides a beautiful principal boy (Miss Jean Carson)…It gives us a fresh and unspoilt principal girl (Miss Julie Andrews) who can sing. It offers once again in Mr Nat Jackley a Dame who upholds the best comic traditions of a famous race” (‘London Casino’, p. 6).

Variety: “First of the West End pantomimes was Emile Littler’s London Casino production of Aladdin. His 11th London effort, this show…looks big with all the essential elements of a successful holiday show. Spaciously mounted and laced with ample comedy, Nat Jackley clicks as Widow Twankey and Jean Carson…makes a spirited boyish figure of Aladdin. Julie Andrews, 16-year-old, proves a delightful vocalist as the Princess” (’International’, p. 13).

Daily Telegraph: “Emile Littler’s Aladdin [is] one of the best shows of its kind for years. It has everything you want…: a glittering spectacle, good singing, a certain amount of dancing, just enough story, and plenty of rich fruity comedy…Julie Andrews, a very young Princess, is…impressive [with] the range of her singing…A first rate show” (Bishop, p. 3).

The Stage: “[T] his is uncommonly good entertainment – the best…of ‘Emile Littler’s eleven London laughter pantomimes’. In Nat Jackley and Jean Carson it has a dame and principal boy of exceptional quality…Young Julie Andrews sings with almost operatic power and beauty” (’Christmas Shows’, p. 5).

The Sketch: “Aladdin, elaborate and pictorial,…chunners along blithely, thanks to Nat Jackley’s Dame, a contorted giraffe. And Julie Andrews has the best singing voice in the three main pantomimes” (Trewin, p. 55).

Daily Mail: “Emile Littler’s 11th London pantomime, gay without being gaudy,…is triumphantly British and pantomimic…Jean Carson is as jaunty and glamorous as a redheaded Aladdin as you could wish, and 16-year-old Julie Andrews, as the Princess, sings with a faintly puzzled air, as if sharing our surprise that such a powerful voice should emerge from such a petite throat” (Wilson, p. 5).

West London Observer: “Emile Littler’s eleventh annual pantomime, Aladdin (London Casino) seems rather like a rolling snow-ball to have got larger and larger during its passage through the years. The present panto has 15 spectacular scenes, irrelevant diversions – clowning, acrobatics, and what-not – not to mention Mr Littler’s own version of the Aladdin legend. This has Nat Jackley as Widow Twankey – great fun in the best and broadest style – and Jean Carson as a cute Aladdin…Julie Andrews and Martin Lawrence supply fine singing voices” (‘Spectacle’, p. 6).

Daily Worker: “Emile Littler’s production…really succeeds in telling an honest story tunefully, colourfully, cleanly and well…Nat Jackley of the rubber-neck made an extraordinarily attractive as well as funny Widow Twankey. The splendid singing of Martin Lawrence, Jean Carson, and Julie Andrews set a first-rate standard” (D.D., p. 3).

News Chronicle: “This, the first pantomime of the London season, is an affair of genuine gaiety and glitter…It has an unusually dainty Widow Twankey in Nat Jackley (who, moreover, has never been funnier), an unusually audible Aladdin in Jean Carson, [and] an unusually musical Princess in Julie Andrews” (Dent, p. 3).

The Sphere: “Mr Jackley as the Dame upholds the best comic traditions of pantomime, giving us a ludicrous parody of beauty with flashing eyes, raven hair and an air of roguishness. Julie Andrews, as the principal girl, is in excellent voice” (‘Aladdin and Humpty Dumpty’, p. 3).

Birmingham Gazette: “The stage gleams and sparkles in this production of Aladdin…Jean Carson is a gallant principal boy and Julie Andrews a strong-voiced principal girl” (‘London Letter’, p. 4).

Any Littler panto was assured of a popular reception but these excellent reviews helped make Aladdin a smash hit of the 1951 Christmas season. It played to packed houses right throughout its two-and-a-half month season closing on 23 February after 103 performances. Theatregoers who couldn’t get tickets to the show weren’t left completely unsatisfied as excerpts from Aladdin were recorded and broadcast as a special half-hour radio programme on the BBC on January 3 1952 (‘Light Programme’, p. 33). It is not known if this recording is still in existence but what a treat it would be to hear it.

References:

‘Accent on Comedy in New Pantomime.’ Coventry Evening Telegraph. 10 October 1950: p. 4.

‘Aladdin and Humpty Dumpty: The lure of the pantomime.’ The Sphere. 5 January 1952: p. 3.

Andrews, Julie. Home: A memoir of my early years, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2008.

Ashton, Ellis. ‘Music Hall Miscellany.’ The Stage and Television Today. 1 June 1978: p. 4.

A.T. ‘Feast on Pantomime Opens in Leeds.’ The Yorkshire Post. 24 December 1949: p. 6.

‘Author! Author!’ The Sketch. 16 January 1952: p. 60.

‘Baby Terry.’ The Coventry Herald. 19 August 1932: p. 7.

Beaumont, Cyril. ‘Ballet in Pantomime.’ The Sunday Times. 30 December 1951: p. 7.

Bishop, George W. ‘Theatre Notes: West End plans for pantomime.’ Daily Telegraph and Morning Post. 29 October 1951: p. 6.

‘Boy Acrobat from Coventry, The.’ Coventry Evening Telegraph. 29 February 1952: p. 11.

Chang, Dongshin. Representing China on the Historical London Stage: From orientalism to intercultural performance. London: Routledge, 2015.

‘Chit Chat.’ The Stage. 3 January 1952: p. 18.

‘Christmas Greetings.’ The Stage and Television Today. 16 December 1982: p. 40.

‘Christmas Shows: Casino Aladdin.’ The Stage. 3 January 1952: p. 5.

‘Christmas Holiday Shows: The Casino Goody Two Shoes.’ The Stage. 29 December 1950: p. 5.

‘Concert Notes: Opera to pantomime.’ The Stage. 22 November 1951: p. 6.

D.D. ‘Vintage Year for Panto: Aladdin.’ Daily Worker. 20 December 1951: p. 3.

'Debroy Somers.’ The Stage. 29 May 1952: p.3.

Dent, Alan. ‘It’s Gay and Glittering.’ Daily News. 20 December 1951: p. 3.

Dixon, Stephen. ‘Nat Jackley: 100 funny walks.’ The Guardian. 21 September 1988: 39.

Elmes, Simon. Hello Again: Nine decades of radio voices. London: Random House, 2012.

‘Emile Littler Sends Greetings.’ The Stage. 20 December 1951: p.5.

Emile Littler Souvenir, The. London: Dewynters Ltd, 1953.

E.M.M. ‘Comedy Pair Great Fun.’ Derby Evening Telegraph. 31 August 1948: p.2.

‘Events from our Social Diary.’ The Sketch. 2 January 1952: pp. 12-13.

From, Gerald. Oh, Yes It Is: A history of pantomime. London: BBC, 1985.

Hainaux, René. Stage Design throughout the World since 1935. London: Harrap, 1965.

‘Hastings Mann’, The Stage. 14 May 1964: p, 3.

Hobson, Harold. “Christmas Shows.” Sunday Times, 23 December 1951, p. 2.

Holloway, Tony. ‘Stage a Big Bouquet for “Cactus” Couple.’ The Pantagraph. 1 March 1969: p. A-7.

‘International: London Pre-Xmas Stage Prems Hit Best Since May; 'Crook’ Looms Okay.’ Variety. 185 (3), 26 December 1951: p.13.

‘Jean Carson Makes TV History.’ The Stage. 10 March 1955: p. 11.

‘Jimmy Clitheroe.’ The Guardian. 7 June 7, 1973: p. 5.

Johnson, Gill. ‘Research reveals life of “Clitheroe Kid”.’ Lancashire Telegraph. 17 May 2007: p. 12.

Knox, Collie. ‘Candid Cameo: Emile Littler.’ The Sketch. 10 December 1947: p. 314.

Konig, George. ‘Prelude to Christmas: The panto factory.” The Sketch. 23 November 1949: p. 450-51.

‘Light Entertainment.’ The Stage and Television Today. 30 September 1976: p. 3.

‘Light Programme: Thursday 3 January.’ Radio Times. : p. 33.

Lloyd-Williams, Anne. ‘Physhe surprised the Americans.’ Birmingham Gazette. 24 January 1952: p. 4.

‘London Casino: Aladdin.’ The Times. 20 December 1951: p. 6.

‘London Letter: Littler and good.’ Birmingham Gazette. 21 December 1951: p. 4.

M.M. ‘Manchester Hippodrome: Jack and Jill.’ Manchester Evening News. 24 December 1948: p. 3.

‘Martin Lawrence.’ The Musical Times. 124: 1684, June 1983: p. 378.

‘Nat Jackley.’ The Stage and Television Today. 13 October 1988: p. 35.

News Chronicle Reporter. ‘Aladdin loses his hat.’ Daily News. 20 December 1951: p. 3.

‘Obituary: Miss Terry.’ The Stage.15 February 1973: p. 19.

Pedrick, Gale. ‘Emile Littler: Producer of two hundred pantomimes’, The Stage, 19 December 1957: p. 8.

Percival, John. ‘Backward Glances: The Metropolitan Ballet.’ Dance and Dancers. February 1960: pp.20-22

‘Principal Girl in Aladdin.’ Daily News. 15 December 1951: p. 5.

‘Provincial Pantomimes.’ The Stage. 31 December 1948: p. 8.

Rasmussen, Frederick N. ‘Harry R. Rosofsky dies at age 90.’ The Baltimore Sun. 11 September 2010: p. A14.

Reilly, Kara. ‘The Tiller Girls: Mass ornament and modern girl.’ In Theatre, Performance and Analogue Technology: Historical interfaces and intermedialities, K. Reilly, ed. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013: pp. 117-132.

Rosen, Gary. Frank Staff and his role in South African ballet and musical theatre from 1955 to 1959. Dissertation. University of Cape Town, 1998.

‘Ross and budgerigars arrive.’ Evening News. 7 December 1951: p. 1.

Seattle Rep. ‘Remembering Biff McGuire.’ SeattleRep.org. 1 April 2021 <https://www.seattlerep.org/about-us/inside-seattle-rep/remembering-biff-mcguire/>

‘Seven-and-a-half Pantos’. The Stage. 16 October 1952: p. 3.

‘She Gets TV Chance.’ Daily Herald. 9 July 1951: p. 5.

Short, Edgar. London Theatre, 1919-1949. London: Wiseman, 1983.

‘Spectacle Galore!’ The West London Observer. 28 December 1951: p. 6.

Stevenson, W.B. ‘Show Piece: Pre-London tryout for new show.’ Nottingham Journal. 18 February 1953: p. 4.

Storey, Basil. ‘The Windmill Tilted.’ Speedway Gazette. 4 December, 1948: pp. 4-5.

Taylor, Jeffrey. ‘Obituary: David Davenport.’ The Stage. 7 December 1995: p. 36.

‘Terry’s Juveniles.’ The Era. 30 March 1921: p. 14.

‘Terry Triumphs.’ The Era. 28 May 1930: p. 11.

‘Theatre Fare.’ The Courier and Advertiser. 24 December 1951: p. 3.

Trewin, J.C. ‘The Pantomimes.’ The Sketch. 16 January 1952: p. 55.

Tucker, David C. Lost Laughs of '50s and '60s Television: Thirty sitcoms that faded off screen. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland, 2010.

‘Variety News: Desmond and Marks welcomed behind ‘that’ curtain.’ The Stage. 11 October 1956: p. 3.

Varty, Anne. Children and Theatre in Victorian Britain: ‘All work and no play.’ Houndsmill: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008.

‘Walter Crisham.’ Plays and Players. August 1985: p. 53.

Waters, Bill. ‘Forsooth! Here cometh Biff and Jeannie.’ Miami News Entertainment Section. 5 April 1964: p. 3.

Wearing, J.P. The London Stage 1950-1959: A calendar of productions, performers, and personnel. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Wilson, Albert Edward. Pantomime Pageant: A procession of harlequins, clowns, comedians, principal boys, pantomime-writers, producers and playgoers. London: S. Paul & Co, 1946.

Wilson, Cecil. ‘Aladdin Is Gay but Not Gaudy.’ Daily Mail. 20 December 1951: p. 5.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2021

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

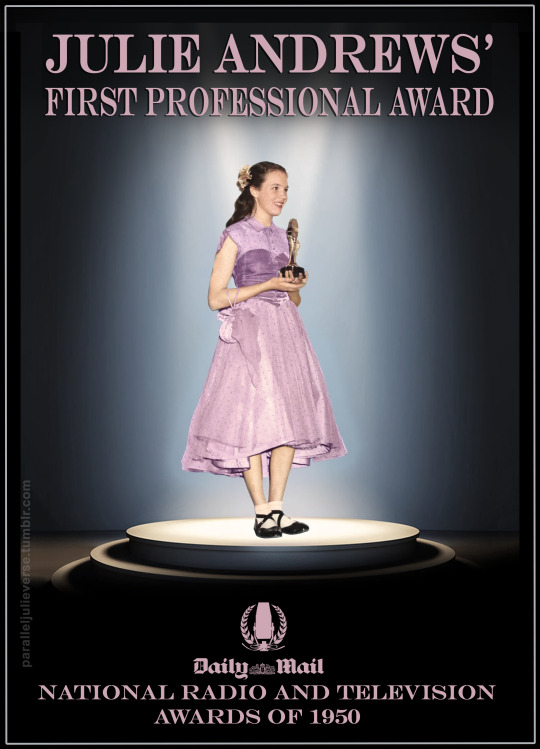

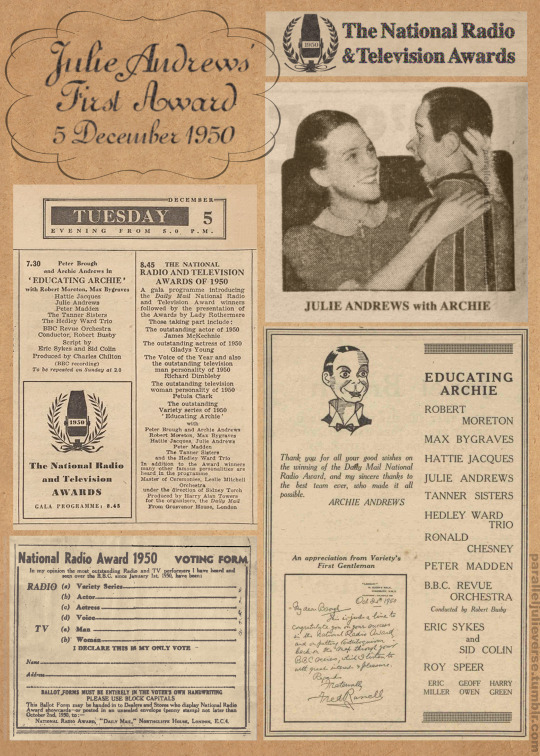

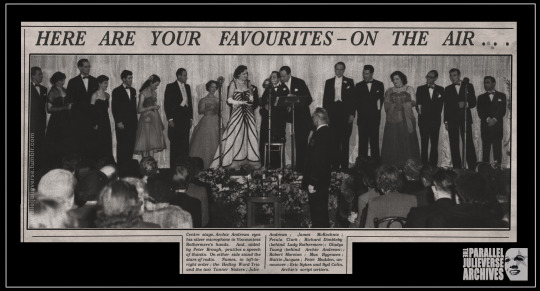

From the PJV Archives: Julie Andrews’ First Professional Award, 5 December 1950

The Parallel Julieverse could not be more delighted by recent news that the 48th AFI Life Achievement Award Gala Tribute to Julie Andrews will finally take place next June, having been postponed twice already due to Covid. In making the announcement, Bob Gazzale, AFI President and CEO, remarked: “Julie Andrews has sent spirits soaring across generations” and the AFI Tribute will “celebrate her in a manner worthy at a time the world needs it most” (AFI 2021). Our 2022 calendar is already circled…

While we wait for our Dame to receive this latest honour, we thought it might be fitting to shine a light on a much earlier accolade from the long and garlanded career of Julie Andrews. In fact, it was the very first professional award received by Julie when she was just 15-years-old on 5 December 1950. That this week happens to mark 71 years since this award was bestowed makes the post all the more timely.

As profiled in an earlier blog entry, in June 1950, Julie joined the cast of a new BBC comedy radio programme called Educating Archie, starring ventriloquist Peter Brough and his dummy, Archie Andrews. Cast in a recurring minor role as Archie’s neighbourhood chum, but principally on board as the show’s resident singer, Julie performed weekly on Educating Archie for two full seasons till early 1952. It was a fortuitous career move for the young star as Educating Archie proved a phenomenal hit, becoming the most popular radio show of the 1950s in Britain with a weekly audience in excess of 15 million, more than a third of the national population at the time (Elmes, p. 208). The programme thus gave the young singer a massively expanded showcase, bringing her voice into the sitting rooms of postwar Britain on a weekly basis and helping make her a household name.

As a sign of Educating Archie’s meteoric success, the programme was voted the ‘Best Variety Series’ at the end of its very first year in the National Radio and Television Awards of 1950.The Awards had only been launched the preceding year in 1949 as an initiative of the British Radio Industry Council with sponsorship from the Daily Mail newspaper (Street, p. 233). Previously, there had been no official forum for honouring British radio talent and the Council wanted to implement an annual award ceremony similar to those of other entertainment industries such as film and theatre (“Highest award”, p. 3).

Dubbed ‘Silver Mikes’ in reference to the 12-inch microphone-shaped trophies given to winners, the National Radio Awards were determined by popular vote with ballot forms published weekly in the Daily Mail and available at over 15,000 stores and radio shops throughout the nation (”Tommy Handley”, p. 1). Prizes were initially awarded in four core categories: Variety Series, Actor, Actress, and, Voice of the Year. For the 1950 Awards, two additional categories were added to accommodate the burgeoning new medium of television – TV Man and TV Woman – with the competition formally rechristened: the National Radio and Television Awards (’Choose’, p. 3).

The hasty addition of television to the 1950 Awards was a portent of brewing changes in the British mediascape that would, ironically, consign the newly minted Radio Awards to cultural obsolescence in a few short years. Though it couldn’t have been known at the time, the Awards were launched during what would prove to be a rapidly dimming twilight for broadcast radio in Britain. Television would soon become the nation’s preferred medium of domestic entertainment and, by 1954, the British Guild of Television Producers and Directors would initiate their own industry-specific awards (Kenny, p. 320). As a result, the National Radio Awards would only last for six years, hosting their final ceremony in 1955 by which stage, as David Kynaston (2009) notes, “there was just a whiff of the last hurrah” about them ( p. 354). Despite the brevity of their tenure, the Silver Mikes were roundly embraced by radio professionals and audiences alike in the early 1950s and, even today, they are remembered as “the most cherished prizes of the airwaves” during the Golden Age of British radio with a “roll of honour [that] was decorated with some of radio’s greatest names” (Jenkins, p. 13).

Meanwhile, back in 1950, competition was heating up for that year’s Silver Mikes. Although Educating Archie had only been on the air for a few months when voting started in September, it quickly emerged as a firm favourite to take out the top spot in the most popular Variety Series category (Wilson, “Archie, Petula…” p. 3). This category had been won the previous year by Take It from Here, a long-running BBC comedy sketch show which had, incidentally, played a role in Educating Archie coming to the air when network producers were looking for a fill-in programme to run during Take It From Here’s annual summer hiatus. Take It from Here was in competition again in 1950, along with several other strong contenders such as Ray’s a Laugh, Have a Go, and, Much-Binding-in-the-Marsh (“And the next object”, p. 5).

In the end, the booming popularity of Educating Archie proved unbeatable and the show easily took out the top award for Variety Series – a feat it would repeat for three years running. Unlike other competitions, the National Radio Awards announced winners in advance of the ceremony, so the cast of Educating Archie already knew in early-November that that they had won Best Variety Series. Joining them as winners of the remaining categories were: James McKechnie (Best Actor); Gladys Young (Best Actress); Richard Dimbleby (Voice of the Year); Richard Dimbleby again (TV Man); and, Petula Clark (TV Woman) (“The Show” 1950).