it's me, i'm here. up and at'em! blog originally created for MDA20009 Digital Communities, but now it's basically a crapshoot tumblr.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

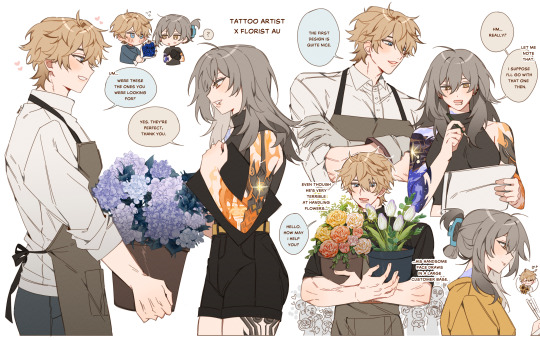

We all know that Hsr is full of references to popular shows. But how to explain it from the point of view of the protagonist? How did the hero have knowledge about this? what if..

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“But if you wanna go look for some fun yourself, I won’t stop you. I mean, after all….”

After all, Elio didn’t put it in the script. Why would it matter?

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

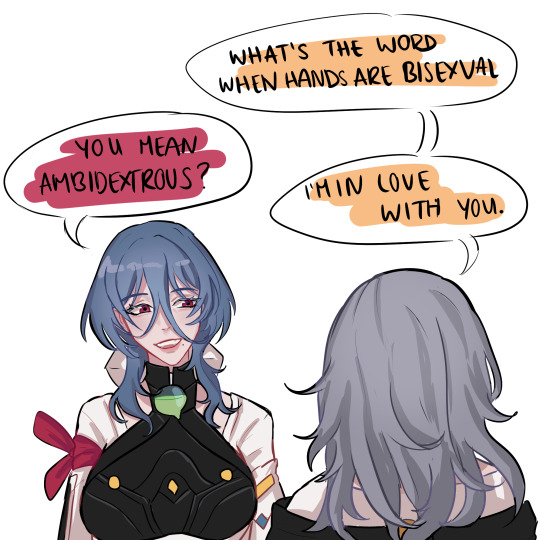

just gettin all the star rail stuff outta my system

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Apparently people are saying Pela from Honkai Star Rail and Sucrose from Genshin Impact are the same character. And I would just like to say that Pela is canonically a smutty fan fic writing shipper and Sucrose would be bedridden for three days for even having the thought.

They are not the same.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyone tried this yet? Bc if not then uh here you go

Here’s a drawn version too :>

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

[TITLE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK]: Protesting in the People’s Republic

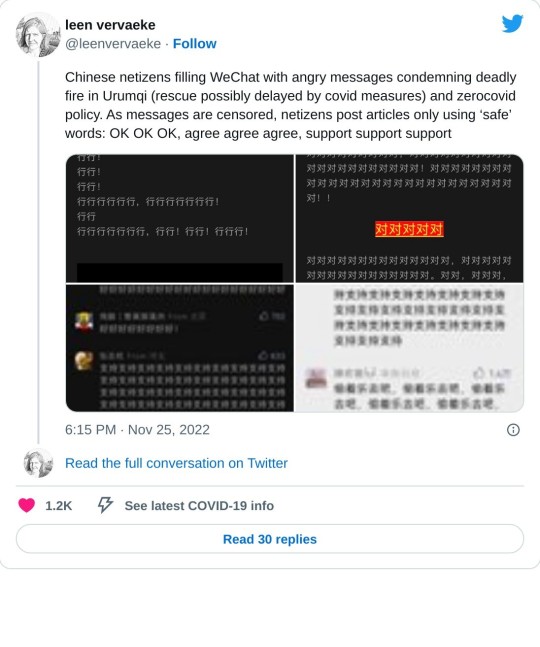

It is a universally known fact that the People’s Republic of China is perhaps not the most magnanimous to the freedom of speech of its citizens. In the past, we have seen China’s authoritarian government crack down on citizen protests by any means necessary: whether that be forced disappearances, disinformation, or rolling tanks into public squares. These past atrocities have cast a long shadow upon China’s recent history and social movements; many activist movements in China peter out due to state-sponsored efforts against them. However, with the recent anti-COVID measures protest stemming from the tragedy of a deadly fire in Urumqi, we may yet see a new paradigm through which protests spread in China: through social media savvy.

As discussed in Qin, Stromberg, and Wu (2019, pp.7-9), the centralised, controlled nature of Chinese social media actively stems the tide of protest; in either active or reactive ways, the Chinese government can respond to calls for protests that do spread on apps like Sina Weibo. However, the sheer speed of social media mitigates these issues to an extent: activists have leveraged them to spread movements and protest tactics far and wide across China. In the recent Urumqi protests, we have seen these tactics spread in real time. As Perrigo (2022) notes, protesters against the Zero-COVID regulations and fire in Urumqi have taken to displaying a blank sheet of paper to express their discontent: a move both symbolic of “everything protesters wish they could say but cannot” and practical as a move to “confound online censors” and gain a better chance for their message to come through amidst heavy censorship. In addition to this, to circumvent censors on the discussion of these protests and highlight the ridiculousness of Chinese censorship, Sina Weibo users have taken to simply posting affirmative characters or ‘censored’ black squares in support of these protests (Yu 2022).

View on Twitter

To an extent, the usage of these tactics on Sina Weibo and other social networking apps within the Great Firewall of China’s infrastructure has yielded results unprecedented in China’s recent history: Mao (2022) reports that China’s government has yielded on its strictest Covid policies and lifted lockdowns in major cities in the aftermath of these protests. The occurrence of these protests has also indicated major changes in China, especially with regards to its activist culture: as the online sphere grows more malleable, the CCP government faces issues in quelling general protests that can spread across broad swathes of its newly-protest-hungry society (Hurst 2022).

In essence, even amidst the immense centralisation and government control of China’s social media, activists have found methods through which their voices can be heard, and their actions mobilised to affect change in a system often cited for its risk of violent suppression of dissent.

References

Hurst, W 2022, “What the protests tell us about China's future,” Time, Time, viewed 8 December, 2022, <https://time.com/6238800/china-protests-reveal-about-the-country/>

Mao, F 2022, “China abandons key parts of zero-covid strategy after protests,” BBC News, BBC, viewed 8 December, 2022, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-63855508>

Perrigo, B 2022, “Why a blank sheet of paper became a protest symbol in China,” Time, Time, viewed 8 December, 2022, <https://time.com/6238050/china-protests-censorship-urumqi-a4/>

Qin, B., Strömberg, D. and Wu, Y., 2019. Social media, information networks, and protests in China. Work. Pap., Stockholm Univ., Stockholm, Swed.

Yu, C 2022, “China's zero-Covid Anger is erupting,” The Spectator, viewed 8 December, 2022, <https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/chinas-growing-anger-over-zero-covid/>

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Visible Pixels: Representation in Gaming and Esports

nanobomb my beloved

Gaming: what is it? Who does it? Why do my kids ask if I have them on my phone? Video games as a medium have come a long way from Pong: games today have multifaceted storylines, more pixels than there are grains of sand on Earth, and most importantly for today’s discussion, characters and players of various intersectional identities playing together. For a scene that is normally seen as heavily male-dominated, Clement (2022) reports that the demographic of gamers these days is evenly split between male and female gamers; Henderson (2020) states that 10% of gamers surveyed also identify as LGBTQ+ to some degree. Now, what does this demographic change mean for the gaming community as a whole?

Firstly, recent games have been delivering a lot of representation: Webb (2022) cites numerous examples of representation of strong women, LGBT+ characters and ethnic minorities in recent video games as diverse as the non-binary Bloodhound from the battle royale shooter Apex Legends and Krem from the medieval role-playing game Dragon Age: Inquisition. This representation also has its depths: as Kamen (2016) discusses, Overwatch revealed one of its heroes, Tracer, as lesbian with a 12-page comic on her relationship with her partner. The presence of these characters provide individuals from these backgrounds with a fleshed-out character that they can relate to and feel seen through; this also serves as normalising and supporting their identities to the gaming community at large, to an extent.

Within gaming communities, while a heavy masculine bent remains, there are efforts to bring about spaces in gaming for marginalised communities. In the competitive scene for Valorant, a 5v5 team-based first-person shooter (a genre considered heavily male-dominated), organisations such as Galorant and the developers Riot Games have made steps towards creating events for women and other people of marginalised genders: this has led to the first international women’s LAN championship for the game being held recently in Berlin (Robertson 2022). MacDonald (2022) also reports that there has been an increasing fanbase for queer Twitch streamers and queer gaming Discord servers where LGBT+ people can meet and team up to game together. In essence, this helps provide a strong community aspect for many of these gamers who may be otherwise isolated in less-than-conducive environments for people like them, whether that be online or off-line.

However, the patriarchal nature of the online gaming community does rear its head every now and then: players who pick characters who are written with LGBT+ identities can often get homophobic slurs thrown at them, while some level of fetishization occurs for some of these characters, especially from men towards female lesbian characters (Nesseler 2022). Black and Latine gamers are targeted for cyberbullying based on their race (Peckham 2020). A level of misogyny and queerphobia permeates a lot of the general gaming space, with epithets relating to these aspects of identity thrown around willy-nilly.

In conclusion, the gaming sphere possesses numerous benefits for marginalised communities, despite its generally male-dominated demographic. However, the marginalised that do participate in online gaming often face discrimination and negative impacts that are not felt by most gamers. Thus, the communities formed by these individuals are more so a mechanism through which they may continue to enjoy the positives of social gaming while avoiding the pitfalls that the general community has.

References

Clement, J 2022, “U.S. gamers by gender 2022,” Statista, viewed 7 December, 2022, <https://www.statista.com/statistics/232383/gender-split-of-us-computer-and-video-gamers/>

Henderson, T 2020, “10 percent of gamers are LGBTQ+ Nielsen study shows,” OUT, Out Magazine, viewed 7 December, 2022, <https://www.out.com/tech/2020/8/07/10-percent-gamers-are-lgbtq-nielsen-study-shows>

Kamen, M 2016, “Overwatch confirms first lesbian character,” WIRED UK, WIRED UK, viewed 7 December, 2022, <https://www.wired.co.uk/article/overwatch-reveals-first-gay-character>

MacDonald, K 2022, “Meet the gaymers: Why queer representation is exploding in video games,” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, viewed 7 December, 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/games/2022/jul/27/meet-the-gaymers-why-queer-representation-is-exploding-in-video-games>

Nesseler, C 2022, “Video game players avoid gay characters,” Scientific American, Scientific American, viewed 7 December, 2022, <https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/video-game-players-avoid-gay-characters/>

Peckham, E 2020, “Confronting racial bias in video games,” TechCrunch, viewed 7 December, 2022, <https://techcrunch.com/2020/06/21/confronting-racial-bias-in-video-games/>

Robertson, S 2022, “VCT Game Changers championship 2022: Scores, bracket, and results,” Dot Esports, Dot Esports, viewed 7 December, 2022, <https://dotesports.com/valorant/news/vct-game-changers-championship-2022-scores-bracket-and-results>

Webb, J 2022, “Diversity in games: The best (and worst) examples of representation,” Evening Standard, Evening Standard, viewed 7 December, 2022, <https://www.standard.co.uk/tech/gaming/video-game-diversity-representation-a4461266.html>

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is a Fan if Not a Mini Wind Turbine?: The Power of Being a Fan in [PRESENT YEAR]

note: this blog post is probably going to be a lot more touchy-feely and a lot less ‘academic’ because i just finished my fandom essay pls let my potato brain give way to my cringe heart for a quick 500 words

I have something difficult to confess: I… like things.

I’m a fan of media and video games and music and movies. I also like talking about the aforementioned things: whether it be The Front Bottoms’ latest singalong folk-punk song about being uncomfortable, Jacob Geller’s recent video essay somehow tying together a 60s alternative song with a 2022 interactive movie about immortality, or a quirky indie game’s pivotal exploration of trauma, I can’t stop myself from shouting about it from my rooftop (metaphorically, not literally, though I’ve come close).

In that sense, it’s kind of nice that the Internet exists. It’s like a neighbourhood where everyone is constantly shouting. All of the time.

now, not all fandoms are black holes of content, but they do become those, surprisingly often. it's kinda concerning ngl

In my years of being a fan of things, I’ve done many things: I’ve been in Discord servers discussing the finer parts of why Kel from Omori is actually the Most Affectionate Golden Retriever Brick of a character in the entire game; I’ve both read and written fanfiction about my favourite ships and laughed/cried/emotionally reacted to them on both sides of the author-reader divide; I’ve bought actual merch from games and content creators I love (no regrets, easily one of my favourite statement tees I’ve ever bought).

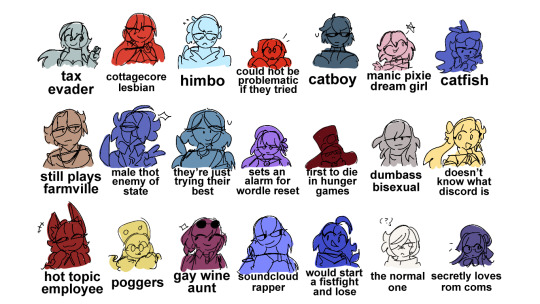

In a more substantive, more objective way of seeing it, through fandom, I’ve been able to interact with so much more people through the lens of fandom. Through being in online fandoms for games like Valorant and Omori, I’ve connected with people around the world over a shared interest that I would have never had the chance to otherwise. In the thriving fanart communities on Twitter, I’ve seen how artists from around the world take the basis of the works they have before them and use it as a springboard for their own ideas, cultures and identities: the sheer depth of intersectional Valorant agent OCs and Pokemon headcanons are a topic due for their own long-form video essay alone. Especially as someone still trying to figure out who or what they are, the positivity and feedback that one can get while exploring identity through the lens of fanfiction and fanart communities (either as viewer, creator, or commenter) can be an enormous source of relief and perspective.

i'm not aroace, but pretty good example of the uniqueness that the queer half of Valorant's fanbase comes up with as OCs!

In short, I feel fandom has been a pretty good part of my life for a pretty good part of my life. Of course, not everything is perfect: toxicity exists as in any online community, and bad actors are always a concern in an anonymised setting. These concerns aside, I find it easy to say that fandom in many different communities has played a substantial part in making me who I am today.

Live long and prosper!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Doing Unto Others: How Malaysians Stepped in When Their Government Failed Them

As most of us at this point in history are aware, pandemics and healthcare situations can have an incredibly wide-reaching area of effect on our society. We’ve also found out the extent to which… certain parties can fall short in responding to these viruses and their collateral effects. However, where giants may fall, heroes amongst us may rise. It is with this in mind that I will discuss the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia, the subsequent lockdown/MCO-mania, and the power and impact of the #KitaJagaKita (translating to #WeLookOutForEachOther) and #BenderaPutih (translating to #WhiteFlag) movements.

In Malaysia, the COVID-19 pandemic and its rapid spiral began with the first Movement Control Order (MCO) in 2020; since that point, there have been two additional MCOs through 2021 and the early half of 2022, accompanied by politicking, continued pressure on our national healthcare system and the worst economic recession since 2008. All these factors meant that the Malaysian government was uniquely ill-equipped to handle the pandemic in its multi-faceted impacts, with hundreds of thousands in hospital and millions more facing dire financial straits due to layoffs and budget cuts, helped in no part by the bureaucracy and political manoeuvring in this period causing severe delays in aid funds (Lee 2021).

It was in this environment that the #KitaJagaKita movement formed.

In the early days of the pandemic, Malaysian YA author Hanna Alkaf used her platform to highlight various aid organisations operating amidst the pandemic in need of donations to carry out aid distribution on her Twitter (Savitha 2020). This quickly turned into a small movement, with community organisers helping her to assemble these resources and reach out to more people to obtain aid from the community at large. The support this movement received grew exponentially (one might even say, infectiously): its scope gradually expanded to include PPE for front-liners and reaching out to corporations for direct aid (Fernandez 2020).

Alongside this, later on in the year, the movement grew to encompass more localised forms of mutual aid under the #BenderaPutih banner; in which individuals in dire need were encouraged to hang white flags outside their residence to indicate their state to their neighbours (Radhi 2021). This new movement, formed due to the continued economic downturn in the wake of the pandemic, helped to alleviate the impacts of this recession even as government aid was held back due to red tape, without attracting the same level of stigma that may be attached to governmental aid (Rodzi 2021).

While there are no hard statistics to point at due to their nature as decentralised, social-media-driven networks, it is undeniable that #KitaJagaKita and #BenderaPutih had an excise impact on Malaysians; its co-opting by the Malaysian Health Ministry (Rodzi 2021) is a solid testament to that alone. Suffice it to say, through the power of social media, community organising has been bolstered to an extent never before seen.

Where giants may fall, everyday heroes amongst us may rise.

References

Fernandez, P 2020, “Author Hanna Alkaf on how Malaysians are carrying each other through the pandemic via #kitajagakita aid movement,” The Edge, viewed 4 December, 2022, <https://www.optionstheedge.com/topic/people/author-hanna-alkaf-how-malaysians-are-carrying-each-other-through-pandemic-kitajagakita>

Lee, CAL 2021, “Malaysia's #Kitajagakita invigorates political activism and tackles apathy,” Asialink, viewed 4 December, 2022, <https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/insights/malaysias-kitajagakita-invigorates-political-activism-and-tackles-apathy>

Radhi, NAM 2021, “New #benderaputih movement, to assist those in need,” New Straits Times, viewed 4 December, 2022, <https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2021/06/703342/new-benderaputih-movement-assist-those-need>

Rodzi, N 2021, “Malaysians launch white flag campaign to signal distress without begging,” The Straits Times, viewed 4 December, 2022, <https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysians-launch-white-flag-campaign-to-signal-distress-without-begging>

Savitha, AG 2020, “#KITAJAGAKITA: Here's how Malaysians can take care of each other amid movement control order,” Malay Mail, Malay Mail, viewed 4 December, 2022, <https://www.malaymail.com/news/life/2020/03/19/malaysian-author-hanna-alkaf-launches-initiative-to-assist-needy-communitie/1848141>

1 note

·

View note

Text

TikTok is My Doc: Social Media, Mental Illness, and the Double-Edged Sword of Online Self-Diagnosis

Have you ever found yourself accidentally forgetting something and then blamed it on your ‘ADHD brain’? Don’t lie, I’ve seen what you’ve like on TikTok. In the time it took me to finish writing this paragraph alone, I ended up going down at least seven different unrelated rabbit-holes thanks to Twitter and TikTok’s mental health side.

one half of my inner thought process on a daily basis

In recent years, and especially in the post-pandemic times, mental health awareness and self-diagnosis of disorders of the mind have come to great prominence; nearly every second post on TikTok or Tweet relates to some form of mental illness, whether it be ADHD, autism or any other. These usually take the form of callout posts, or discussions of ‘signs you never knew were ADD’, or some other form of relatable points. The reach that these posts have can often be immense: one example noted in Korducki (2022) managed to get over 100 million views across social media platforms that it was posted to. Mental Health Social Media is clearly a bigger deal than a lot of us are consciously aware of.

On the one hand, amidst the pandemic, social media, and mental health-centred communities in general, have proven to be self-organising positive spaces for those afflicted. As Qu & Zhang (2021, pp.39-40) note, social media spaces have offered individuals a space to discuss and disclose very personal and distressing experiences in a way that is simultaneously archival, and safe and controlled for those sharing their experiences; something that is ever the more important as isolation and other related forms of social anxiety continued to grow during the pandemic and ensuing lockdowns. These virtual communities provided a structure of normalcy and socialisation for individuals even when this was not possible in the physical realm. In addition to this, the rise of ADHD-aware social media has led to an increase in people getting diagnosed for ADHD and learning to cope with their living conditions under the affliction: as a case study in Reed (2022) notes, one Canadian struggled with the symptoms of her ADHD in the pandemic before being able to recognise them as such through identification on TikTok and finally being able to get diagnosed; the ADHD TikTok community not only helped her to recognise her own symptoms, but provided a space for them to share experiences and coping strategies with ADHD. In a sense, it can be said that the awareness and community that modern social media has brought into the foray of mental health has had an immense positive effect on those affected.

However, it’s not all a bed of Ritalin: the idea of mental health as it’s often viewed on social media has quickly become a place ridden with the pathologizing of the most common of behaviours. As noted in Jennings (2021), even things like being an early advanced reader in childhood have been self-identified as trauma markers or signs of a greater mental illness. More concerning is the increasing trend of “treating mental illness like subculture”: the identification of oneself with a pigeon-holed identity related to their mental illness. Not only is this divisive and somewhat reductive, but it could also lead to more reliance on identification as a crutch, and somewhat inversely, more stereotyping of those afflicted by conditions like ADHD or BPD.

Suffice it to say, while the outpouring of support afforded by social media platforms in the modern age is largely positive, it might be worth considering how we approach the topic, so that we can mitigate its downsides and its potential for worsening the lives of those afflicted.

References

Jennings, R 2021, “How mental health became a social media minefield,” Vox, Vox, viewed 3 November, 2022, <https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2021/9/30/22696338/pathologizing-adhd-autism-anxiety-internet-tiktok-twitter>

Korducki, KM 2022, “Tiktok trends or the pandemic? what's behind the rise in ADHD diagnoses,” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, viewed 15 November, 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/jun/02/tiktok-trends-or-the-pandemic-whats-behind-the-rise-in-adhd-diagnoses>

Reed, A 2022, “The pandemic drove these Canadians with ADHD to online communities, and they're better for it | CBC news,” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, viewed 3 November, 2022, <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/canadians-adhd-awareness-1.6610606>

Qu, C & Zhang, R 2021, “The role of online communities in supporting mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic,” XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 38–41.

1 note

·

View note