various things related to the ming dynasty period of chinese history. sometimes art reblogs, sometimes original content.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

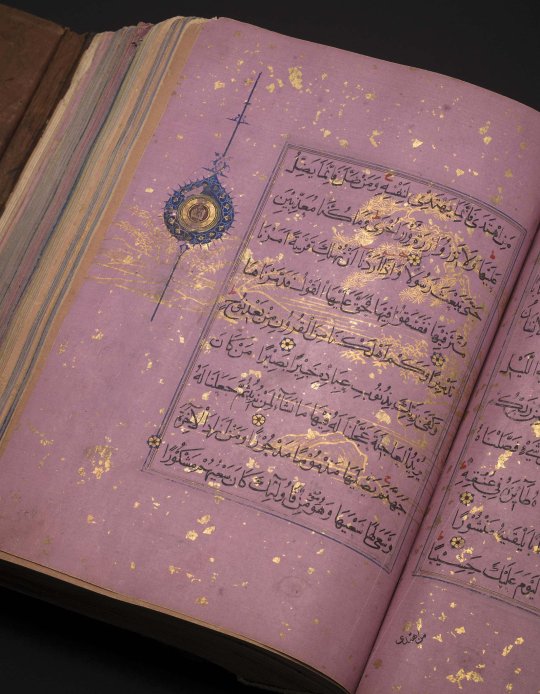

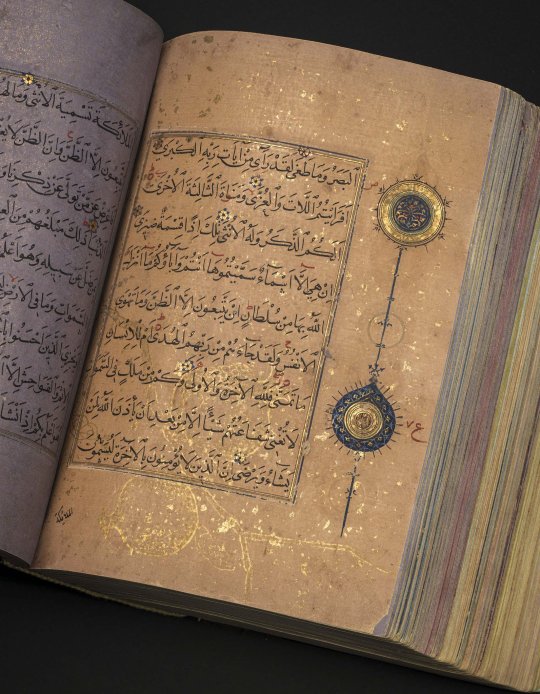

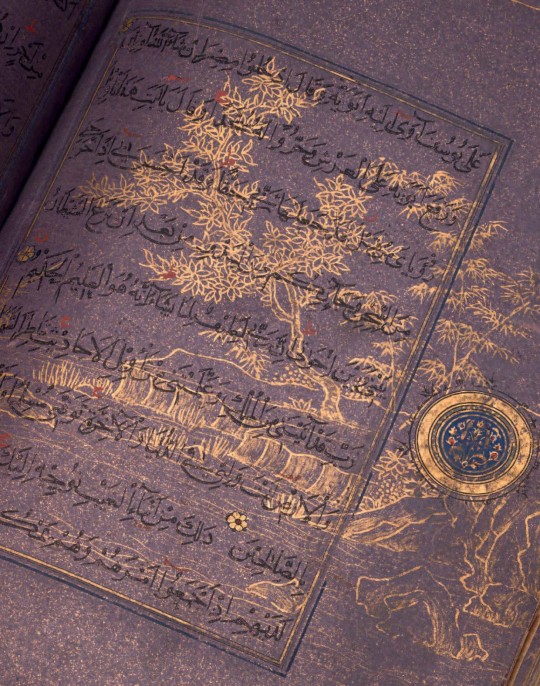

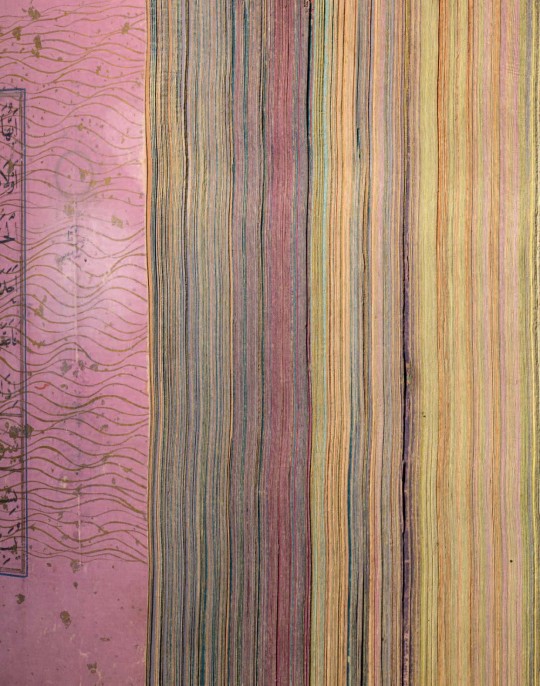

15th century Timurid Qur'an copied on Chinese paper from the Ming Dynasty.

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Globalization In One Object

Ming Vase (circa 1540-1550) with Chinese designs on the stem and a Portuguese armillary sphere on the body.

566 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bi Zhu - Warrior poet

Bi Zhu was a Chinese warrior woman who not only avenged her father’s death, but also wrote a poem about her combat experience.

Her story took place during the transition between the Ming and the Qing dynasty. Bi Zhu’s father was a Ming official. She was 20 when he received a post in Jiqiu (present day Heibei province) and accompanied him there. In 1642, her father’s was killed during a battle against the Qing troops and the enemy kept his body as a trophy.

His soldiers wanted to wait for reinforcements before trying to retrieve his corpse, but Bi Zhu knew that they would take too much take to arrive. Instead, she launched a night attack on the Qing camp while the soldiers were celebrating their victory. It was a success, Bi Zhu beheaded the enemy general and screamed: “Those who dare to resist the imperial (Ming) army will suffer the same fate!”. The Qing soldiers fled, and Bi Zhu retrieved her father’s body. She then buried him in Jinling (present day Nanjing).

Bi Zhu also recounted her martial exploit in a poem:

(Qin Xiu whom she refers to in this poem was a legendary woman said to have avenged her parents’ death against all odds)

My father vowed to serve his country; he died in battle at Jiqiu.

The enemy rode his horse; the plundered his corpse.

Had I not avenged him I would have been put to shame by Qin Xiu.

Seizing the advantage of surprise,

At night we entered to fight those animals, a thousand strong.

We killed the enemy, shedding blood like rain. I held up the general’s head.

The mob trampled each other; bodies filled hollows and ditches.

My father’s corpse, carried home in a coffin,

Buried simply at the base of a remote mountain.

I hope my wise and brave countrymen,

Will rise together to fight our foe.

When the moth-like invaders are exterminated,

Our nation will be forever whole, like a gold vessel.

Having accomplished her filial duty, she married a commoner named Wang Shengkai and withdrew from the world after the collapse of the Ming dynasty. The couple dedicated their lives to studying. She wrote this poem about her life as a recluse:

The curtain at our door at the water’s edge is a mat

Content to be poor, my husband doesn’t want to build a family fortune.

Why ask if there’s food for the morrow?

He grasps the “duck mouth” hoe and plants plum blossoms.

Bibliography:

Bailey Alison, “The severed head speaks: Death, revenge, moral heroism and martyrdom in sixteenth to seventeenth-century China”, in: Strange Carolyn, Cribb Robert, Forth Christopher E. (dir.), Honour, violence and emotion in History

Lin Yanqing, Lee Lily Xiao Hong, “Bi Zhu”, in: Lee Lily Xiao Hong, Wiles Sue (dir.), Biographical dictionary of Chinese women: Tang through Ming (618-1644)

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Eunuchs Could Marry

According to Chinese official historical records, there had been a historical record of eunuch marriage as early as the Eastern Han Dynasty. But they were not common until the Ming Dynasty. Starting in 1402, the Yongle Emperor quietly began allowing eunuchs to marry, as thanks for their significant contributions in Jingnan Rebellion which nearly knocked Yongle off his throne. From then on the marriage of eunuchs had legitimacy because it had the tacit approval of the emperor. The Yongle Emperor even awarded wedding to eunuchs who made significant contributions. These were, for obvious reasons, marriages for intimacy and companionship not children.

Eunuch marriages remained common in the imperial court through the end of the Qing Dynasty in 1912.

398 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold Phoenix Hairpin

From China’s Ming Dynasty, found in the tomb of Prince Zhuang of Liang, the ninth son of the Hongxi Emperor. He died in 1441 so the phoenix was made in 1441 or before.

It is actually one of a pair. Imagine wearing two items, this intricate and this heavy, on your head!

663 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellow as the Emperor’s Color

In China, yellow has long been associated with the Center - one of the five directions, along with the four cardinal points. Yellow was first perceived as the Emperor’s color during the Tang era (618-907), but not any yellow - only one particular hue: 赤黄, literally “reddish-yellow”. This rich and bright color was associated with the sun, and the sun was the symbol of the Emperor.

Initially, under the Tang, “reddish-yellow” was not forbidden for ordinary people to wear, and was not set by law as the Emperor’s color: wearing it was just the personal choice of some emperors. Then, during the reign of Emperor Gaozong, “reddish-yellow” was forbidden to be worn by commoners. In the Tianbao era (the second half of the reign of Emperor Xuanzong), the Emperor’s bedding, formerly purple, was replaced with “reddish-yellow”, and the officials were forbidden to wear this color. It’s can be said that in China the perception of yellow as the Emperor’s color began from that period.

However, figurines and frescoes from the Tang era show that yellow (just not the “reddish-yellow”) was still very popular among the people of the Tang empire.

Also, during the Tang era, yellow, together with white, was one of the colors assigned by law to the lowest-level officials, soldiers, commoners and the like. Most yellow dyes are cheap, easy to produce and easy to apply to fabric, so in general yellow was considered a commoners’ color.

The Emperor’s yellow (“reddish-yellow”) vs the commoners’ yellow:

Still, the color of the Emperor’s ceremonial dress under the Tang was not “reddish-yellow” - it was, as in antiquity, deep black, combined with scarlet.

Tang Emperor with his retinue, a mural from Dunhuang:

Only in the Ming era (1368-1644) another variant of yellow - ocher 赭黄 - became the official color of the Emperor’s ceremonial dress, and both officials and commoners were forbidden to wear any shade of yellow.

Under the Manchurian Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), ocher in the Emperor’s costume was replaced by a lighter and brighter hue - 明黃 “bright yellow”.

Now this particular hue is still the one most strongly associated with the Emperor. In many dramas and movies, Emperors of the pre-Qing dynasties wear “bright yellow”, however, this is historically incorrect.

I’d like to add that the fact that some color was considered the Emperor’s color didn’t mean that the Emperor was doomed to wear only it. While the Emperor’s ceremonial dress had to conform to the color regulations (Tang - black with scarlet, Ming - ocher, Qing - bright-yellow), in their daily life Emperors were free to wear any color they liked.

734 notes

·

View notes

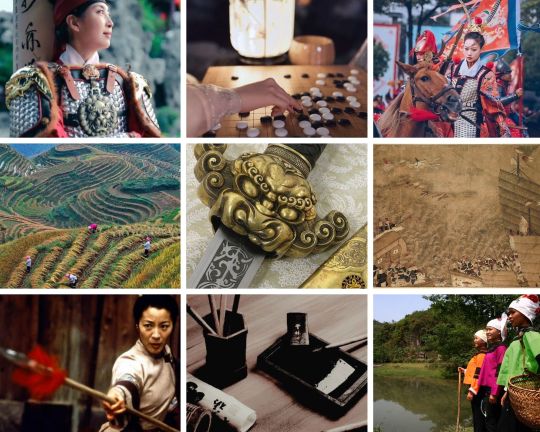

Photo

Lady Washi - Ferocious warrior and administrator

Lady Washi (1498-1557) was a woman of Zhuang ethnicity. Her father was the sub-prefectoral magistrate of Guishun, present-day Jingxi, Guangxi province, China. She was taught military strategy and martial arts during her childhood.

Lady Washi was married to Chen Meng, the local leader of Tianzhou (present-day Tianyang). In 1523, Chen Meng ignored his wife’s advice and rebelled against the imperial Ming government. He was ultimately killed by Lady Washi’s father. One of Chen Meng’s sons, Chen Bangxiang, took his father’s place, but Lady Washi killed him after he raided her lands.

She then petitioned the court, asking for Chen Meng’s grandson, Chen Zhi, to be allowed to inherit the position and be placed under her care. Her request was granted. Lady Washi thus became regent as Chen Zhi was too young to rule. He died in 1553 and Lady Washi then served as a regent for his son.

She was a talented administrator who had her people’s trust. Lady Washi also proved instrumental in fighting the Japanese pirates who made incursions on the entire eastern seaboard. In 1555, the emperor named her female assistant regional commander. At that time aged of 57, Lady Washi led 5,000 soldiers in battle, killing many pirates, and acquired a reputation as an accomplished warrior.

She thus helped the imperial troops to secure their first victory in this long campaign and her exploits were celebrated by the local people. The emperor awarded her with silver coins.

For another woman who fought against the Japanese pirates, see Lady Qi.

If you want to support me, here’s the link to my Ko-Fi.

Bibliography:

“Lady Washi”, in: Lee Lily Xiao Hong, Wiles Sue (dir.), Biographical dictionary of Chinese women: Tang through Ming (618-1644)

Mou Sherry J., “Wa”, in: Higham Robin, Pennington Reina (ed.), Amazons to fighter pilots, biographical dictionary of military women, vol.2

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

the battle of buyur lake: today in the ming dynasty

tldr; in 1388 on may 17, ming forces led a wildly successful attack against the northern yuan

The story begins back in 1387. The current emperor of Ming China sends a military campaign of 200,000 soldiers to defeat the Uriankhai Mongols. The campaign was successful and resulted in the surrender of their enemy- thus, not long after in 1388, the emperor sent another campaign after the Northern Yuan.

150,000 soldiers, led by General Lan Yu, left to take on Uskhal Khan Tögüs Temür. They headed to Daning, following the steps of the previous campaign, and pressed on to Qingzhou, where they were told that the Yuan were encamped at Buyur Lake (also Buir Lake, from 捕鱼儿 bu yu er). Accordingly, they crossed the Gobi Desert until they arrived.

approx map of their journey by me; sorry if it formats weird

As they approached, they did not see the Yuan and considered returning home, but did not head back for fear of wasting their journey. Soon finding new intelligence as to their whereabouts, the Ming army attacked under cover of darkness, catching the Yuan off guard.

The battle was a huge success- Ming casualties were negligible and over 80,000 Yuan and 150,000 domesticated animals were captured, probably including Tögüs Temür's younger son.

However, Tögüs Temür himself was not to enjoy his escape for long. Fleeing the Ming army, he was found and killed by an Oirat. It wasn't long before the Mongol tribes lost their unity and the Oirats replaced the Yuan in power.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Chinese Ming Dynasty Period, Jiajing Wucai dragon teapot

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

the encouraged suicide of widows in ming china (pt 1: financial)

There's a lot to cover on this, so it's going to be broken up into multiple parts.

It's important to mention before we begin that women (or perhaps even more often, girls) in ancient China would be considered widows even if they had only been betrothed by their parents to the dead man- they did not have to be formally married or even have met. Everything here applies to them as well as traditional widows.

Now that that's out of the way, meet our hypothetical widow. Her husband has just died- what does she do next?

A modern woman may try to make the best of her new property and lifestyle. Let's see why this wasn't a viable option for Ming widows.

While Ming wives could inherit property, they were often seen as very vulnerable and naive (which could be true) and were fiscally preyed on by men in the community or even their husbands' family. These men would attempt to intimidate the women into giving up their property, or convince them that a man deserved the property more.

Their husbands' families also had no reason to be supportive- the woman in question has essentially just taken their property. As long as it remains in the family (the woman continues to take care of her husbands' parents, etc) it might not be a problem- but this was not a guaranteed option, and not everyone wanted an extra woman hanging around. If the widow were to remarry, she would be moving their wealth to another family- also unacceptable. Therefore, the men in the family sometimes tried to take advantage of her potentially vulnerable state and coerce her into giving up the property before doing anything else.

So this woman has the choice between either being hounded constantly while also having to mourn (guarding coffins, taking care of parents, being very secluded- emotionally taxing things) or just giving up the property. Without economic stability, life would've been very hard, and many widows committed suicide for this reason.

Why didn't they just remarry and start a new life, you may ask? I thought I'd be able to fit that in, but this is already very long, so I'll cover the concept of chastity and why it was so important in the next part.

0 notes

Text

A Jingdezhen Dish

This blue and white porcelain dish with a glorious leaping horse is from Jingdezhen kilns in China, and dates back to 1640. Jingdezhen is a city located in southern China that is known for pottery production. It became a major kiln site around the first millennium, and by the 14th century it was one of the largest producers of Chinese porcelain in the country. From the time of the Ming dynasty, beginning in the late 14th century, the Jingdezhen kilns came under the control of the emperor, producing imperial porcelain in large quantities. This particular object was made during a period of political unrest and civil war as the country transition from Ming to Qing dynasties throughout the 17th century. During this time, the large scale manufacturing of Imperial porcelain collapsed, the trade was opened up to a range of private customers. This led to major changes in the style, influence and subject matter of Jingdezhen ware.

300 notes

·

View notes

Text

about liu rushi, the famed crossdressing courtesan and banned poet

can't actually find a source for this image so maybe don't trust it

this one is legit though

Liu Rushi was one of the Eight Beauties of Qinhuai (some of the most famous courtesans of the Ming Dynasty who lived on the Qinhuai River). She was born in 1618. Her family sold her at a very young age to marry a government official, but a series of (un?)fortunate events led her to become a courtesan.

Upper-class courtesans in the Ming Dynasty were some of the most educated women of their time, pushing the boundaries of womens' social status. They were trained in art, poetry, and music and were given a much higher value in wide society.

Due to this, Rushi had become an acclaimed painter and poet by the time she was seventeen.

one of her paintings

She dabbled in romances with many scholars, but none worked out due to societal standards at the time. Eventually, she met and began to pursue Qian Qianyi, a reputable scholar. She often dressed in men's clothes- when they first met (she requested he review her poetry) he thought she was a man.

Just a year later in 1641, they got married. Technically she was a concubine, but Qianyi appears to have treated her like a principal wife. They had a formal ceremony, and he attempted to continue to satisfy her scholarly curiosity by providing books and places for her to study. He aided her on many occasions and treated her as an equal.

Rushi continued her habit of crossdressing through her marriage, and would often wear men's clothes publicly, sometimes posing as her husband.

Soon after in 1644, the Ming dynasty collapsed, replaced by the Qing. Rushi, being a fiercely patriotic citizen, attempted to convince Qianyi to commit suicide with her as an act of martyrdom. He initially agreed, but backed out later and stopped her from doing it herself.

They continued a sort of subtle resistance against the Qing until 1664, when Qianyi died at the age of 81. Pressured by the Qing government and other nasty types, Rushi committed suicide the same year. The Qing emperor removed both Rushi and Qianyi's works from printing, accusing them of rebelling against the Qing.

For further reading:

Tales of Ming Courtesans by Alice Poon (book, English)

Liu Rushi (book, Mandarin)

Liu Rushi (movie, Mandarin)

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WANLI or TIANQI c.1600 - 1627 Ming Porcelain wine ewer

Courtesy: Robert McPherson Antiques

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Prints from the Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu, China, 1633

Studio of the ten bamboos founded in Nanjing by Hu Zhengyan

491 notes

·

View notes