within a few lines of saying Hello, you're already asking for my location ... why ?🍿 O-H ... 🧩

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

They started to fight for Africa when they started to eat too much of the continent.

FVCKERS THEY ARE

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Timbuktu - Africa's Forgotten Library

Timbuktu, to many that name is simply a term for "middle of nowhere", somewhere you'd go to if you didn't come back in home by dinner, and many don't even know it was a real place, on the other side of the Sahara from Morocco.

And if you look deeper, Timbuktu isn't just a place but one of the greatest intellectual centres of the Medieval era.

It didn't hold just books but a reflection of Sub-Saharan's intellectual hub, who's library was the largest in the world for centuries.

"View of Tombouctou from a hill" from Rene Caille's Journals, 1830

On the subject of historical libraries, the Library of Alexandria and the loss of scrolls is never one to miss. It is the subject of countless mourning for the 400,000 books that burned down (though that story isn't really true).

Yet, Timbuktu's libraries are home to an estimated 700,000 manuscripts dating back as far as the 11th century, almost double what was in Alexandria, about science, law, astronomy, health, philosophy, and more.

This number is so large it was only in the late 19th-century when British Library recorded hitting that milestone, centuries after the printing press.

And unlike the common belief that it was simply copies of Arabic texts, there were many, many original texts were written by West African scholars from Mali to Nigeria to Sudan, thinking and philosophising on concepts not seen elsewhere.

And unlike the unrecoverable books of Alexandria, Timbuktu's books are still out there, not in massive public libraries but hidden in homes, cellars, basements, under wells and beds. Away from the colonialist powers around the city that till this day keep trying to destroy its tradition.

So if one singular West African city is home to a unique repository of culturally distant Medieval knowledge larger than any seen at the time, why isn't it more well known?

Abdel Kader Haidara, director of the Bibliotheque Mama Haidara De library looking through manuscripts in his house. Photographed by National Geographic, Sep 2009.

Historians may debate the origins of Timbuktu in different languages and different etymologies, but local tradition dating back to the 17th century at least indicates that it's in the name itself:

Around 1000AD, among the northern tributaries of the Niger, sat a water well used by pastoralists and merchants crossing the Saharra, this much we do know of.

Oral tradition preserved in the manuscripts state that the well was cared for by an elderly woman named Buktu. The area became known as "Tim-Buktu", Buktu’s Place.

Her legacy, like many women in Timbuktu's history, was never erased and also reflects the more egalitarian society that it was known for.

"Arrival at Timbuktu" circa 1100 AD in Tifinagh and Magrashab Ajami, depicting a caramel caravan greeted by Buktu, edited from a print of Timbuktu in 1891 as I couldn't find any depictions of Buktu.

As an essential stop on the trans-Saharan route, it eventually became a permanent dwelling growing in size, becoming a commercial market and later a place of education.

And around the same time, Islam was spreading in Africa.

But you see, the stereotype of a religion spread by conquest wasn't true in West Africa, it was too hard to reach. It was spread through Islamic merchants that came and settled in cities, creating their own class of citizens.

These merchants created communities of learning, law, and commerce, and gradually over time converted people, taught others, and created a shared community based on Islam. Cities across West Africa had this revolution in time, but Timbuktu was the northern door leading the way. It was small at first.

Mansa Musa, king of the Mali Empire between 1317-1354, from the 1375 Catalan Atlas. His caption reads "This king is the richest and noblest of all these lands due to the abundance of gold that is extracted from his lands"

But then came Mansa Musa, that guy, the richest man in history. His story is one most of us know and is a whole post on its own but he's the key originator of this story.

After travelling back from Mecca in 1324, he saw potential and peacefully annexed the city of Timbuktu on his way, full of ideas from what he found in the great cities he passed through.

He funded the already existing mosques and brought in scholars from North Africa, wanting Timbuktu to also be a city of scholars, as the gateway from North to West.

And it worked.

An 800 year old pre-Mali Empire Qur'an from the the year 1215, illuminated manuscripts were common among the Qu'ran found in Timbuktu, often incorporating local textile motifs mixed with Islamic geometry.

At its peak in the 16th century, it had a population of 100,000 people with 25,000 of its inhabitants being scholars. That's a quarter of a city engaged in education on a level unlike any other city in the world.

Mosques like the Sankoré Madrassa, a place of learning created around the same time as Oxford University, became libraries, classrooms, lodges for pilgrims, and more above the place of worship, and started writing tens of thousands of books.

These madrassa's were places where scholars could convene with their students rather than a strict university setting.

In Timbuktu, it wasn't a school's prestige that was important but the teacher that was most important, and usually the children of the teachers also became teachers, creating a culture of families renowned for their intellectual prowess.

Public libraries weren't common but scholars had their own big libraries. Ahmad Baba lost 1600 books in the Morroccan invasion, which his student famously commented was the smallest library out of any library in his family.

And unlike modern and ancient stereotypes, they created literature and developed entirely new genres of literature, and a new form of Islam too still practiced today.

The Sankoré Madrassa in Timbuktu, photo by Bert de Rulier

Timbuktu was remote, that's hard to deny, but it's fame was certainly not. Scholars from Morocco and Egypt came to study, coming from societies where differing views on religion could be deadly they were shocked at the wildly different and unique debates and hadith in Timbuktu.

One famous story tells of an Egyptian scholar coming to teach in Sankoré, but humbled by those around him that he became a student. This wasn't unusual, and Timbuktu's fame was in the pride of this sort of environment.

This relative flexibility of thought in Timbuktu was because of its remoteness, away from the strict standards of the North who couldn't keep a watchful eye.

Conversions to Islam were done through cultural negotiation and persuasion, creating an Islam more tolerant of local African traditions, yet always respecting the Quran. This was something that famous Moroccan traveler Ibn Battutta infamously found horrifying in his 1350 visit to the Mali Empire.

And women were part of the conversation too, Nigerian scholar Usman dan Fodio, famous for innovating the famous Sokoto literary tradition in northern Nigeria, was part of a family that believed in gender equality.

His sisters were known to read and write, copy manuscripts, take care of his libraries, and Fodio's daughter Nana Asma'u became the most famous female poet, polyglot and teacher in West Africa. She formed a cradle of female teachers called jajiss who travelled across the region teaching women to the same standard as men did.

Tolerance and apathy for keeping the faith are reasons some modern researches would lead you to believe the rationale for this cultural mix, but it was simply a different blend that always ultimately followed the Quran.

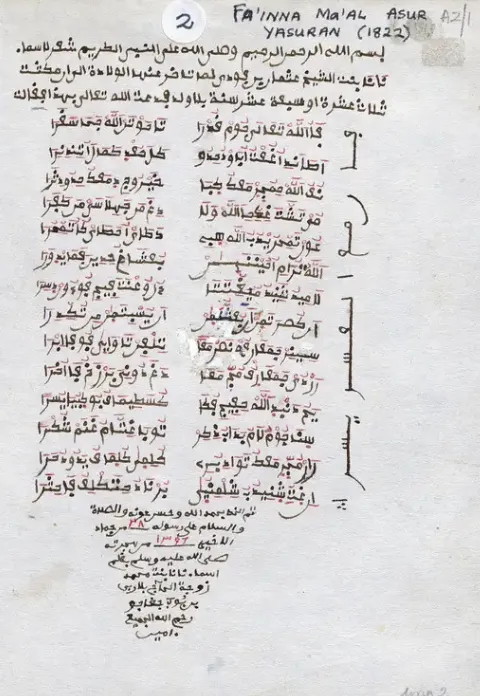

One of Nana Asma'u's works, written in her mother tongue Fulfulde, 1822

Each town often had its own mufti, these were trained judges who handled local disputes: marriage, trade, inheritance, and even gossip. They wrote to other scholars for advice, receiving detailed legal rulings. These texts with the legal rulings are called fatwa.

Fatwas are a treasure trove of local legal reasoning, especially in West Africa where we see different approaches and belief systems compared to other regions. Topics ranged from dowry rights, camel disputes, and even cheating scandals.

West African fatwas reveal a lively, flexible, and deeply contextual Islamic world that often debated concepts in ways unthinkable in the Arab world.

And this is one of Timbuktu’s greatest contributions, pioneering an African scholarly tradition that merged worlds, and brought lived social context into theology.

Looking into specific fatwas and authors and analysing West African Islamic tradition and social roles is for a whole seperate post, but know that through it we can see a completely unique intellectual understanding of Islam forming.

However fatwa's are fairly common across the Islamic world, did Timbuktu or Mali contribute anything groundbreaking? Yes.

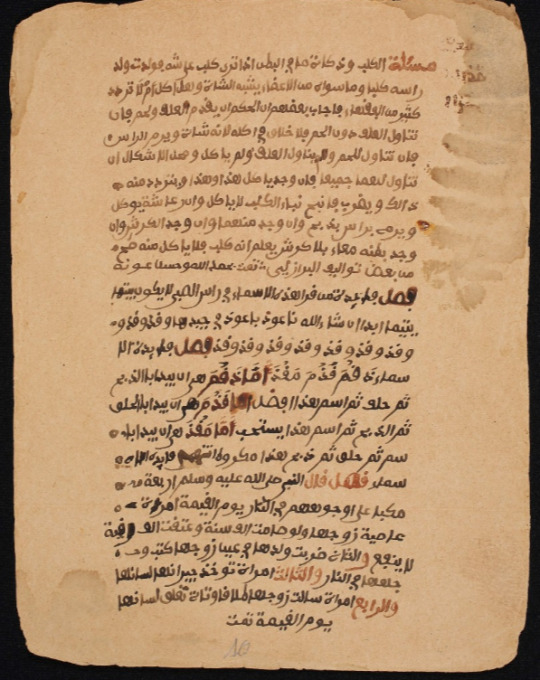

A page from a 19th century commonplace book, starting with a sheep-related fatwa and ending on a note about a hadith.

Timbuktu wouldn't last in its golden age forever, and in 1591 the city was sacked by the Moroccans, destroying manuscripts and destroying tombs. This event started a power vacuum and chaos between rivaling families.

To make sense of it all and to settle disputes on legitimacy, scholars started compiling histories of Timbuktu and the surrounding histories in the Sahel, these were called Tarikhs, historical chronicles.

In 1655, the Tarikh al-Sudan was published, Sudan being a name for the black African regions. It's actually THE primary source for where the histories of the Mali, Songhai, and Ghana empires that we know today come from.

The Tarikh genre in Timbuktu is particularly interesting, however what was revolutionary about it wasn't the text itself but where it was sourced from, oral histories and commentaries.

In most historiographic tradition at that time, only written material was accepted as legitimate for history, and everything else deemed irrelevant. Oral stories were usually performed to teach morality, a lesson, and thus events might be exaggerated or a narrative entirely fictionalised, so academia dismissed it as irrelevant.

But what Abd al-Sa'di realised was that oral histories sung and said by the bards (called griots) were generally very accurate at giving a general yet intimate view of moments in history, where even fiction when critically analsyed could give us deep insights in history. This revolution gave us one of the best examples of historiography in the African continent.

It would take until the 19th century for the West to even consider oral stories/fiction as having historical basis, when a very amateur archaeologist decided to forgo all established convention and believe Homer, in the process finding the city of Troy millenia after its name was first sung.

Many scholars turned to Ajami, the use of arabic script to write local languages, preserve and ideas that otherwise had no written form. The 20+ languages known to be written this way were part of a unique blend that elevated the languages of the people to an equal intellectual status as Arabic, in fact this was so much the case that foreign scholars to the region would often learn Fulfulde due to its prominence.

So knowing the massive, unique, distinct and large literary tradition in the city and abroad, why isn't it more well known and researched?

A more recent copy of the Tarikh al-Sudan sitting in the Metropolitan Museum.

The Moroccan invasions never slowed down the intellectual tradition but made people wary of outsiders. A couple European explorers were known to be murdered in their attempt to visit the city in fear of what they would bring if they brought back news. Teachers taught in their homes instead, if need be children were taught in secret. French colonialisation didn't help matters but people persisted.

After Mali's independence, there was renewed interest in Timbuktu which led to some digitalisation projects. Gathering books included literally knocking on people's doors and convincing them that the foreign researchers would do no harm to the texts, creating libraries with tens of thousands of copies.

In 2012, with a jihadist takeover that was much against what Timbuktu stood for, attempted to get rid of any manuscripts found in the city as part of a push against non-Sharia compliancy. Books were smuggled on rice bags, donkey carts, and re-hidden again with the help of researchers, successfully being able to smuggle a total of 300,000 known books, with many probably still in the city.

Digitalisation has largely been a success with over 150,000 books available in online archives, specifically in the Virtual Hill Museum & Manuscript Library. However, a tiny minority are translated and studied and even less are readily available. This was due to efforts prioritising conservation before research, and so it's knowledge remains underappreciated simply because the wide world doesn't yet have easy access and interest in it yet.

Timbuktu is a city of many wonders to uncover, and may it stand as a testament that West Africa, and the continent more broadly, has always been a cradle of knowledge, history, and depth the world can no longer afford to overlook.

READ MORE:

Hill Museum & Manuscript Library - Contains thousands of manuscripts I used for statistics

African Bibliophiles: Books and Libraries in Medieval Timbuktu by Brent Singleton - Interesting research on its book keeping and intellectual culture

Beyond Timbuktu An Intellectual History Of Muslim West Africa by Ousmane Oumar Kane - A book moving away from the Western lens on Timbuktu, with takes and information I found so fascinating I'll write much further on these topics when I finish reading it.

The Meanings of Timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie and Souleymane Bachir Diagne - Fascinating deep dive, with many examples I used, into many specific aspects of the manuscripts I'd need many more posts to explore.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have never seen a leader of a Nation disrespected by a journalist this way, but here we are. The attitudes of the British are unweilding in their deflection into finding so many reasons why resources they brutally extracted from the Caribbean should not be returned to us.

BITCH

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mali Empire: An In-Depth Analysis of Africa’s Great Economic and Cultural Powerhouse

Introduction: Mali – The Wealthiest Empire in African History

The Mali Empire (1235-1600 CE) was one of the most powerful, wealthy, and influential civilizations in African history. Located in West Africa, Mali was a centre of trade, scholarship, military strength, and cultural excellence. It controlled vast resources, including gold, salt, and ivory, making it one of the richest empires in history.

From a Garveyite perspective, the Mali Empire is a critical study for Black people today because it proves that:

Africa was the centre of world wealth and innovation long before European colonization.

Black leadership and governance flourished through advanced trade networks, military strength, and education.

Self-sufficient Black nations can thrive when they control their own resources and institutions.

The story of Mali is one of African excellence, Pan-African unity, and Black self-determination.

1. The Origins of the Mali Empire

A. The Rise of Mali from the Ghana Empire

Before Mali, the Ghana Empire (300-1200 CE) was the dominant power in West Africa, controlling gold and salt trade.

After Ghana declined due to internal strife and invasions by the Almoravids (a North African Muslim group), Mali emerged as its successor.

The Mandinka people of Mali, led by Sundiata Keita, overthrew the Sosso kingdom in 1235 CE and established Mali as the new dominant force.

Example: The Battle of Kirina (1235 CE) saw Sundiata Keita defeat King Sumanguru of Sosso, marking the birth of the Mali Empire.

Key Takeaway: African empires rose and fell, but Black leadership continued to evolve and adapt to new challenges.

2. The Golden Age of Mali: Wealth, Trade, and Expansion

A. Mali’s Control Over Gold and Salt Trade

Mali controlled the richest gold mines in the world, located in Bambuk, Bure, and Galam.

The empire became the world’s leading supplier of gold, making it one of the wealthiest states of its time.

It also controlled the salt trade, which was just as valuable as gold because salt was necessary for food preservation.

Example: Two-thirds of the world’s gold supply in the 14th century came from Mali.

Key Takeaway: Africa was the centre of world wealth—colonialism only reversed this by stealing African resources.

B. Expansion Under Sundiata Keita and His Successors

Sundiata Keita expanded Mali’s territory to include modern-day Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Niger, and parts of Mauritania.

Mali’s military was powerful, using cavalry, archers, and well-organized infantry units.

The empire established a federal system of governance, allowing local leaders to maintain control as long as they pledged loyalty to Mali.

Example: Mali was twice the size of modern France, proving Africa’s historical dominance in governance and territory.

Key Takeaway: African leadership was highly organized and politically advanced, contradicting Western lies about African governance.

3. Mansa Musa: The Richest Man in History

A. Who Was Mansa Musa?

Mansa Musa (1312-1337 CE) is considered the wealthiest individual in world history, with a fortune estimated at over $400 billion in today’s value.

He ruled during Mali’s Golden Age, expanding trade, culture, and Islamic scholarship.

He built mosques, libraries, universities, and urban centres, making Mali the intellectual hub of Africa.

Example: The Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu, built under Mansa Musa’s reign, still stands today as a symbol of African architectural brilliance.

Key Takeaway: Black rulers were some of the wealthiest and most powerful figures in global history—yet their legacies are deliberately erased.

B. Mansa Musa’s Legendary Pilgrimage to Mecca (1324 CE)

Mansa Musa made a famous Hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca, travelling with 60,000 men, 80 camels carrying gold, and a vast caravan of scholars and officials.

He spent so much gold in Cairo that he collapsed the local economy for years.

His pilgrimage put Mali on the map, leading European cartographers to include Mali on world maps for the first time.

Example: The Catalan Atlas (1375), a European map, depicted Mansa Musa holding a gold nugget, symbolizing Africa’s immense wealth.

Key Takeaway: Africa’s economic power was globally recognized before European colonization, proving that Africa was not “discovered” by Europeans—it was already thriving.

4. The Intellectual and Cultural Power of Mali

A. Timbuktu: The Centre of African Scholarship

Timbuktu was home to the University of Sankore, one of the world’s first universities.

Scholars from Mali studied astronomy, mathematics, medicine, law, and philosophy, making Mali a centre of knowledge.

Over one million manuscripts were housed in Timbuktu’s libraries, proving Africa’s literary and intellectual traditions.

Example: Many of the Timbuktu manuscripts are older than European universities, proving that Africa had a scholarly tradition independent of European influence.

Key Takeaway: Black history is more than just slavery—Africa was the home of some of the world’s greatest scholars and universities.

5. The Decline of the Mali Empire: Lessons for Today

A. Why Did Mali Collapse?

Over time, Mali weakened due to:

Civil wars and internal conflicts among ruling families.

Invasions from rival West African kingdoms (e.g., Songhai Empire).

The shift of global trade routes to the Atlantic, bypassing Mali’s economy.

By the 1600s, the once-great empire had fragmented into smaller states, paving the way for European colonization centuries later.

Example: The Songhai Empire replaced Mali as the dominant power in West Africa, proving that African civilizations evolved and adapted over time.

Key Takeaway: No Black nation can survive without unity, economic control, and military strength.

6. The Garveyite Vision: How to Rebuild Mali’s Legacy Today

Africa must control its own resources, just as Mali controlled its gold trade.

Black education must be prioritized, reviving Africa’s tradition of intellectual excellence.

Pan-African unity is necessary—African nations must stop competing and start working together.

Wealth must be reinvested in Black communities, not given away to foreign interests.

Final Thought: Will We Rebuild the Greatness of Mali?

Marcus Garvey taught that:

“The Black skin is not a badge of shame, but rather a glorious symbol of national greatness.”

Will Black people continue to be economically dependent, or will we control our own wealth like Mansa Musa?

Will we rebuild centres of Black knowledge like Timbuktu, or will we continue to let others define our history?

Will we unite as Africans and members of the diaspora, or remain divided by colonial borders and foreign religions?

The Choice is Ours. The Time is Now.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have some news for members of the united states armed forces who feel like they are pawns in a political game and their assignments being unnecessary.

82K notes

·

View notes

Text

rep_kamlagerdove

Trump has created and manufactured violence in Los Angeles to distract from the Republican budget that will strip 16 million Americans of their health care.

His threat to arrest @cagovernor isn’t just an authoritarian escalation—it’s another distraction.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ima just drop this here and let this sister cook! Let sister Queen loose and watch her leave no crumbs and no stones unturned. Jasmine Crockett needs a woman like her by her side when doing the work of the people while against Satan's pawns. WATCH THIS!!! @freedominyeshuaohio

125 notes

·

View notes