Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

In the Name of the Father and of the Mother

We obviously don’t know when we’re going to die. We also do not know when our loved ones are going to pass away either. If we knew when this would happen, we would have a greater sense of urgency to spend time with the older generations and get their story or to tell our own. I am guilty of this negligence. As I have become older, I have so many questions. Those questions could have easily been answered by my grandfather, Maurice Miller who died in 2002. Over the last 10 years, I have become increasingly interested in my family’s history, especially on the Miller side. I have traced this line of Millers to the late 1700s in Columbia County, Pennsylvania. At that point the search had become murky--there are a lot of “Jacob” Miller’s alive during the mid to late 1700s, it is difficult to determine which one(s) are related to me. At one point on this journey, I hit a roadblock. I still might be stuck there even now, if not for a discovery. Initially, I was stuck on my great-great grandfather. I knew that his name was Charles Wesley Miller. I even have a picture or two of him with his family (including my great-grandfather who I never knew). However, it became difficult to find out who his family was because of some circumstances that I can only speculate upon. These circumstances might have become clearer if I only asked my “pap” before he passed.

Charles Wesley Miller was born on December 25, 1850. He lived until January 29th of 1946. Researching his long life became a sort of obsession. To think that someone lived long enough to be aware of the Civil War, the premature death of 5 Presidents while in office, as well as World Wars I & II made me want to know this man. I felt like I needed to ask him questions that I knew academic answers to, but that he would know the real story because he lived it. Of course, I missed my opportunity to ask about him from my grandfather or any of his sisters who would have known Charles in his middle to old age. The best I was able to do was ask an aging distant cousin about him. She only remembered Charles as a “little man” who “pinched” her hard when she was a little kid because he must have had a bad leg and she touched it accidentally. “Cousin Marie” was the only person who I was able to ask about Charles who remembered the man.

My research on Charles began like many amateur genealogists—with trips to the Columbia County Historical & Genealogical Society, a free trial of ancestry.com, some questions to my immediate family, etc. However, the only real record of Charles that I could find concerning his younger years was a census record when he was 20 years old that listed him as a “farm laborer” and living with a family of Kelchners in Mifflinville, PA. The head of household was an “E.A. (Eleazor) Kelchner”, living with his wife Angelina Kelchner (aged 35) and their children. I found subsequent records of Charles’ wife and their children, but nothing prior to 1870.[1] Then I found a “smoking gun” in getting to know Charles better. The Ancestry.com website had not included death certificates in its data base as of the early 2010s. So, I sent a request to the Pennsylvania Department of Vital Records with some fragmented information that I had of Charles, along with the nominal fee, and waited. The death certificate showed Charles was the child of “Angelina Piefer” and “Peter Miller.” I was also able to determine my great-great grandmother’s maiden name (Fetterolf), which is a great story in itself, because Charles was her 2nd husband. In 1870 the eventual couple was living 2 houses away—he with his mom and stepfather and my great-great grandmother Eva living with her first husband. This find gave me renewed energy.[2]

I could deduce that Charles’ mother was, indeed, the Angelina Kelchner that he had been living with in 1870. This led me to wonder: what happened to his father? Was he a Civil War veteran who died during the war, prompting his mother to remarry for support? Who was this “obviously” benevolent stepfather who took in a wife with a child from another man? If Peter did not die in the Civil War or by some other means, what were the circumstances of his leaving? Was Charles adopted? It led me to admire my great-great-great grandmother even more. Imagine a teenage girl, pregnant, left alone after (or before) the birth of her child--intentionally or not—having to fend for herself and her child in the early 1850s--in a society in which she did not have many opportunities to sustain herself, let alone a child. I admired her the more I researched.

Then the pieces started to come together. After her son was born, Peter Miller is reported to be with his father and brothers two counties away in 1851. Apparently, my great-great-great-great grandfather (George) bought 1700 acres and, with his sons (including Peter) “for a number of years engaged in improving the place.” Did Peter (and his extended family) abandon Angelina? Probably. Was this how Peter’s father ridded his family of a disgraceful situation? Maybe.[3] Peter would go on to live in his new area, enlist in the Union army, marry another woman, have more children (including another “Charles”) and die in the 1890s.[4]

I found, through successive censuses, that Angelina never learned how to read or write. I also found that this “benevolent” husband of hers (Eleazor) was placed in prison.[5] He was detained for larceny in 1858 and described as “intemperate.” Angelina was husbandless with at least 3 children under the age of 8 for about a year according to the sentence. After Eleazor died, she was married to a Stephen Wolf (husband #3?). She is supposed to be buried in the cemetery in my hometown, near Eleazor. However, there is no stone. Was she too poor? Was she a harsh mother and her children didn’t see the need (I don’t think so). Or was she humble? Surely, she hasn’t been forgotten. The hardships that were placed on this simple woman made me wonder how she did it. She lived until 1915, until the ripe old age of 84. If it weren’t for her, I wouldn’t be here. Until the birth of my son in 2006 and my nephew in 2012 years after that, my younger brother and I were the last Millers in this line.

Then it hit me. Angelina had the wherewithal to name her oldest child “Charles Wesley.” Now her perseverance through hardship made sense. As a teenage girl in 1850 (living with the Miller family, according to the 1850 census)[6], she thought to name her child after one of the founders of the Methodist church. I want to believe that she was a believer in Jesus Christ. I want to believe that she went to revivals in rural Pennsylvania and was a church goer. I want to believe that no matter how bad her tribulations were, she knew that God had a plan for her, her family, and her descendants. I want to believe she set Charles on a Christian tradition that saw him become a member of the Mifflinville United Methodist Church. It is the church where Charles’ children would be baptized and, eventually where they would become members. When he moved to Berwick, PA, located across the Susquehanna River, Charles became a member of the Berwick First United Methodist Church—where his funeral was conducted (a Kelchner was the funeral director—either his half-brother or nephew—their name is still on the funeral home’s name).[7] Charles’ son, Jordan, became a member of the Beach Haven United Methodist Church after he moved to that community to continue sharecropping. My grandfather, Maurice, was a lifelong Methodist, becoming a 50-year member of the Beach Haven United Methodist church, eventually moving to another Methodist church 10 minutes away. I know that my grandfather was a quiet, confident, and faithful man, attending that church, being a Sunday School superintendent and church council member. My father attended that church beginning in the 1950s and it was the church in which I was baptized with water from the Jordan River (my grandfather’s and my middle name!). It was also the church that I learned the love, grace, and forgiveness of Christ.

I must believe that my path to being a Christian had its start on a cold Christmas in which a teenage mother (perhaps married, perhaps not) decided to name her baby after a true Christian warrior who helped bring his faith to America. Her descendants, including my aunts, cousins, and children all became baptized Christians. I must believe that God had and still has a plan my family. Angelina, in my mind, and then Charles’s stories are the beginning of my testimony, and we are the lasting testament to hers.

[1] 1870 United States Census, Mifflin Township, Columbia County, Pennsylvania, digital image s.v. “Charles Miller,” Ancestry.com.

[2] Charles Miller, Death Certificate, Janurary 29, 1946, Pennsylvania Department of Health, Vital Statistics, copy in possession of author.

[3] Martha CrossSargent, “History of Sullivan County, Part 2,” Pa-Roots, http://www.pa-roots.org/data/read.php?741,661356.

[4] Caroline Cole, Death Certificate, January 30, 1914, Pennsylvania Department of Health and Vital Statistics, Ancestry.com.

[5] Eastern State Penitentiary, Convict Reception Registers, 1842-1929 digital image, Pennsylvania, U.S., Prison, Reformatory, and Workhouse Records, 1829-1971, s.v.” Eleazer Kelchner,” Ancestry.com.

[6] 1850 United States Census, Mifflin Township, Columbia County, Pennylvania, digital image, s.v. “Angelina Peifer,” Ancestry.com.

[7] “Charles Miller Dies at Age 95: One of Area’s Oldest Residents Dies at Home on West Front St,” Berwick Enterprise, January 30, 1946, 1, https://www.newspapers.com/image/817335305/?terms=charles%20miller.

0 notes

Text

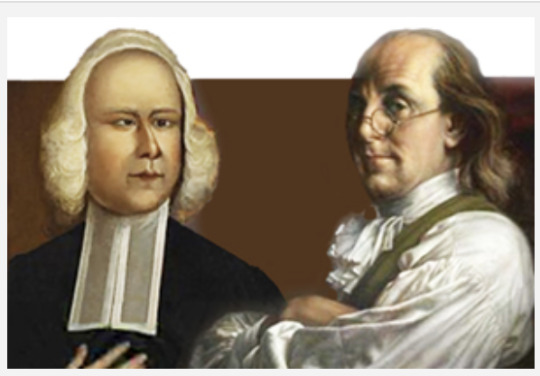

George Whitefield's Influence on Ben Franklin

George Whitefield might have been one of the most famous people living in colonial America during the early to mid 1700s. He was an itinerant preacher who was essential for the success of the Great Awakening. Along with his popularity at revivals, he had an extensive advertising network from which he was able to transmit his many volumes of literature, letters, and pamphlets. Through this, he developed a working relationship that ended up being what might be considered a friendship with the rather skeptical Benjamin Franklin. This friendship seems to be one of mutual respect and one in which Whitefield may have made some inroads to caring for Franklin’s eternal life.

Whitefield became a sensation in the colonies as he utilized his acting background and his keen knowledge of the Bible to get thousands to attend his religious revivals. His popularity had much to do with his plain-spoken message that appealed to people across denominational lines. He noted in a sermon in 1769 that “Christ does not say, Are you an Independent, or a Baptist or Presbyterian? Or are you a Church of England man? Nor did he ask, Are you a Methodist? All of these things are of our own silly invention.”[1] His message was indeed for the masses. His message was delivered and received equally. Men, women, children, all races and creeds were welcome to be converted to Christ. Phillis Wheatley, renown poet and slave, eulogized Whitefield shortly after his death with these words:

“Ye thirsty, come to this life-giving stream, Ye preachers, take him for your joyful theme; take him my dear Americans, he said, Be your complaints on his kind bosom laid: Take him, ye Africans, he longs for you, Impartial Savior is his title due: wash’d in the fountain of redeeming blood.”[2]

His appeal and his message were indeed far reaching.

When reports of tens of thousands attending his orations became common place, “enlightened” minds such as Benjamin Franklin became skeptical. Franklin had already secured business dealings with Whitefield as one of the itinerant’s chief publishers of advanced advertising and religious literature. As Franklin notes, Whitefield was able to move even a skeptical mind to action. Franklin notes that he went to a revival and was determined to not contribute any money to any type of offering that was to be collected. However, as he listened to Whitefield, he noted that he became moved and threw his copper and silver coins that he had on him and “another stroke of his Oratory made me empty my Pocket wholly into the Collector’s Dish, Gold and all,” to the point that all of Franklin’s money was contributing to Whitefield’s ministry.[3] Franklin also used a rudimentary science experiment to determine how many people could hear Whitefield’s sermons to prove (or disprove) allegations that tens of thousands of people could hear him. At a revival meeting Philadelphia, Franklin walked as far away as he could still hear Whitefield speaking and “Imagining then a Semicircle, of which my Distance should be the Radius, and tht it were fill’d with Auditors, to each of whom I allo’d two square feet, I computed that he might well be heard by more than Thirty Thousand.”[4] This “research project” reconciled to Franklin that the reports of the preacher reaching 25,000 people to be not only possible, but probably accurate.

These anecdotes are worthy of mention to not only to prove the connection between Franklin and Whitefield, but to also establish the effect that the itinerant had in softening people’s hearts and bringing them to Christ. There is evidence that Whitefield made inroads in making Franklin more aware of Christ’s love for him. In a letter to Whitefield, Franklin references a conversation that the two men must have had about the meaning of grace versus works as a way to please God. Franklin acknowledged that “even the mixed imperfect pleasures we enjoy in this world are rather from God’s goodness than our merit.”[5] Franklin also accepted that he was willing to “content myself in submitting to the will and disposal of that God who made me, who has hitherto preserved and blessed me.”[6] These statements may not set off alarm bells that Franklin was a true believer in Jesus Christ as his savior, but it is a recognition that God does grant all things and through God, all things are possible. Franklin throughout the rest of the letter enters into a kind of a defense of good works as a means to reflect the will and love of God. He talks kindly of the “faith you [Whitefield] mention” and that he does “not desire to see it diminished, nor would I endeavor to lessen it in any man.”[7] However, Franklin believed that outward works of serving other people was the more important way for people to obtain rewards in heaven. Whitefield may not have succeeded in converting Franklin to the confession, faith and Christ’s divinity as a path to heaven, but they must have had conversations that softened Franklin’s more deist ways of thinking. Most notably, he did acknowledge that “I can only show my gratitude for these mercies from God by a readiness to help his other children and my brethren.”[8] Perhaps, his help in spreading the Word of God through Whitefield’s publications and his support of the preacher was how God worked through Franklin.

[1] George Whitefield, A sermon by the Reverend Mr. George Whitefield, being his last farewell to his friends, (London: Printed for S. Bladon, G. Woodfall, R. Fryer, and by T. Jones, Printer, 1769) 11, Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926 (accessed February 1, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0111858065/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=4aafcd86&pg=1.

[2] Phillis Wheatley. An elegiac poem, on the death of that celebrated divine, and eminent servant of Jesus Christ, the late reverend, and pious George Whitefield, (Boston: [Sold by Ezekiel Russell in Queen-Street, and John Byles, in Marlboro-Street], 1770), Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926 (accessed February 1, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0103367922/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=c79602f5&pg=1.

[3] Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography: An Authoritative Text, edited by J.A. Leo Lemay & P.M. Zall, 1986, http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/becomingamer/ideas/text2/franklinwhitefield.pdf.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Benjamin Franklin and William Temple Franklin, The private correspondence of Benjamin Franklin, LL.D ... : comprising a series of letters on miscellaneous, literary, and political subjects ..., (London: H. Colburn, 1817), 24 Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926 (accessed February 1, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0105468562/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=c04b5f85&pg=24.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

Bibliography:

Franklin, Benjamin. Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography: An Authoritative Text, edited by J.A.Leo Lemay & P.M. Zall, 1986, http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/becomingamer/ideas/text2/franklinwhitefield.pdf.

Franklin, Benjamin, and William Temple Franklin. The private correspondence of BenjaminFranklin, LL.D ... : comprising a series of letters on miscellaneous, literary, and political subjects ... London: H. Colburn, 1817. Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926 (accessed February 1, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0105468562/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=c04b5f85&pg=24.

Wheatley, Phillis. An elegiac poem, on the death of that celebrated divine, and eminent servantof Jesus Christ, the late reverend, and pious George Whitefield. [Boston]: [Sold by Ezekiel Russell in Queen-Street, and John Byles, in Marlboro-Street], [1770]. Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926 (accessed February 1, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0103367922/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=c79602f5&pg=1.

Whitefield, George. A sermon by the Reverend Mr. George Whitefield, being his last farewell tohis friends. London: Printed for S. Bladon, G. Woodfall, R. Fryer, and by T. Jones, Printer, 1769. Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926 (accessed February 1, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0111858065/SABN?u=vic_liberty&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=4aafcd86&pg=1.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ben Bernanke’s Adherence to Friedman and Schwartz’s Monetary Causes of the Great Depression

Ben Bernanke (b. 1953) was a former Chairperson of the Federal Reserve and a leading economist who is a renown monetarist. Bernanke is a disciple of Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz’s milestone theories found in A Milestone History of the United States. Bernanke agrees with Friedman and Schwartz that the Great Depression was caused, in a large part, by policies of contracting the supply of money. Bernanke would take this thesis further by noting the domino effect that occurred because of the restrictive monetary policies of the late 1920s through the early 1930s. He stated that by constricting the supply of money, governmental agencies such as the Federal Reserve caused banks to raise interest rates, thus causing more debt to be incurred by corporations and individuals. Banks were also subjected to “runs” because of their speculative practices and their fear of bankruptcies, which in turn helped propagate a decline in prices and output for the entire country and, eventually, the rest of the world. Bernanke also states that the world-wide depression was worse in countries that adhered to the gold standard or did not relinquish the practice, as it arbitrarily kept prices down. Likewise, he notes that countries who abandoned the gold standard recovered from Depression status quicker than those countries who continued with the custom.

While Bernanke’s views are not new, it is worth mentioning that even though he is a disciple of Friedman/Schwartz, his observations are even more important because of his application of the ideas. His position as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve gave him special insight into determining that the Great Depression was caused in no small part by the policies of that institution during the latter part of the 1920s through the 1930s. In a speech given in honor of Milton Friedman’s ninetieth birthday in 2002, Bernanke stated that the massive and prolonged downturn in the economy was “the product of the nation’s monetary mechanism gone wrong.”[1] He would conclude this speech by stating matter-of-factly: “Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you [Friedman & Schwartz], we won’t do it again.”[2]

Bernanke’s philosophy of what caused the Depression would influence his career as a representative of the Federal Reserve. He noted that it is now “widely accepted” that the money supply policy of the Federal Reserve “turned contractionary in 1928, in an attempt to curb stock market speculation.”[3] As interest rates and deposit reserve mandates rose to diminish the supply of available money caused an influx of gold into the US from other areas of the world and depleted other countries’ supply of money as well, causing more contraction.[4] Making interest rates higher through the late 1920s through the early 1930s “reduced the effectiveness of the financial sectors a whole in performing” the normal banking services, especially in credit lending.[5]

This decline in loans was especially hard on people and businesses looking to obtain credit. According to Bernanke, this may have been an initial reason for the continuing decline in output across the United States throughout much of the 1930s. Of course, banking institutions were worried about bankruptcies and defaults on behalf of their debtors. Even though credit became expensive, Bernanke states that “The seriousness of the problem in the Great Depression was due not only to the extent of the deflation, but also to do the large and broad-based expansion of inside debt in the 1920s.”[6] Large corporations increased their credit by billions in the 1920s and small businesses significantly grew their credit obligations. In turn, banks increased rates to recoup losses and as an insurance on their speculative activities. Banks’ speculation in who to give loans to also proved to be more difficult. Bernanke described the dilemma banks had as trying to distinguish between “good” and “bad” borrowers. He noted that the best borrowers took loans in “order to undertake an individual-specific investment project(s).”[7] Conversely, “bad” borrowers were deemed to have no real investment opportunity and would take on credit that would be squandered trying to only increase output.[8] The irrational loaning of money at these high interest rates and the speculative nature of individuals, banks and businesses caused a crisis in the financial sector.

Coinciding with this crisis, the existence (and maintenance) of the gold standard among other countries also kept world-wide prices down. After World War I, the gold standard was almost universally abandoned by the world’s countries. However, throughout the 1920s, most of the world’s economies slowly reincorporated it until by “1929 the gold standard was virtually universal among market economies.”[9] Although this may have been done to stabilize prices, the gold standard was rather “short-sighted.” The low supply of ready-to-use money reflected the real economic outputs connected with low prices and only worsened after the banking crisis and contraction policies that were continued through the early 1930s.

Expounding upon Friedman & Schwartz’s monumental work, Bernanke made clear his philosophy on the major causes of the Great Depression. He noted that the real problem had to do with the monetary policy of contraction that included high fractional reserve requirements and high interest rates to curb rampant speculation. However, these policies combined with irrational banking policies and most countries’ reliance on the gold standard made the Depression worse and more prolonged.

[1] Ben Bernanke, “On Milton Friedman’s Ninetieth Birthday,” The Federal Reserve Board, November 8, 2002, https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2002/20021108/default.htm.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ben S. Bernanke, “The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 27, no. 1 (1995): 6. https://doi.org/10.2307/2077848.

[4] Ibid., 7.

[5] Ben S. Bernanke, “Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression.” The American Economic Review 73, no. 3 (1983): 257. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1808111.

[6] Ibid., 261.

[7] Ibid., 263.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Bernanke, “The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression…,” 4.

0 notes

Text

Pierre S. Dupont

Pierre S. DuPont (1870-1954) was an American businessman, entrepreneur, and philanthropist who was instrumental in advancing his family’s holdings in the early 20th century. Many DuPont family members had begun and maintained numerous endeavors since the mid-19th century. However, Pierre DuPont was not a person who would rest on his laurels (and the accomplishments of his ancestors). He was instrumental in utilizing systematic management styles to move DuPont into the modern world in which he focused on the management process, rather than the final outcomes, specific processes and procedures rather than the end result.

Any discussion of Pierre DuPont (or any DuPont, for that matter) is a matter of family and family history. The DuPont legacy was essentially formulated when “General” Henry DuPont who took over a debt-ridden company after his father’s death. He was the quintessential example of what Ernest Dale calls “Caesar Management” style. Henry DuPont immersed himself into the business, being the sole man in control—directing every move, micromanaging daily activities of the business, and knowing every detail of the goings-on—including when each of his workers had “a birthday, had a baby, or was drunk on a Saturday night.”[1] Although this “one-man control” of the DuPont family business was workable for the times and the energetic Henry DuPont, he did exhibit some management characteristics that he might have passed down to his descendants. He grew DuPont into a huge business day emphasized quantity over quality, which would lower prices. He also emphasized speedy delivery of his powder and easy/strict payment methods that would make paying for his products more efficient. Finally, he placed agents in high need areas like the coal fields of Pennsylvania or the gold mines of California to encourage and expedite the purchasing process as needs would arise. He also was able to do most things in-house, including, but not limited to, construction of plants, secretarial work, engineering and distribution. He was also able to create a kind of cartel by organizing the Gunpowder Trade Association in order to lower competition and protect several firms against price cutting. [2] However, Henry DuPont’s management style fit his time and his personality. When he died, his management style was impossible to duplicate. His nephew, Eugene DuPont took over. Although Eugene had a brilliant chemical mind, he did not have the business sense or mentality to continue in the same vein as Henry. After Eugene’s death, the company was in danger of being sold to a competitor. The threat of this sale opened the door for Pierre DuPont, along with his cousins Albert and Coleman, to buy the company for $2,100 and over $12 million in loans.[3]

With this they modernized the company’s management system. They built research labs, staffed them with PhD experts and “marketed new products like paints, plastics and dyes.”[4] At the head of this reorganization was the re-incorporation process that was done in New Jersey in 1903—because New Jersey allowed companies to own other companies’ stock. In this fashion, the three DuPont cousins were able to bring in other family businesses under one big conglomerate.[5] The genius of this maneuver was that DuPont could exploit the market in chemicals, explosives, and other products more effectively. However, the cousins stopped short of creating an all out monopoly, rather they aimed to “achieve more certain market power by exploiting potential scale economies.”[6] Short of making a monopoly, Alfred spoke for the other cousins by stating “you could always count upon running full if you make cheaply and control only 60% [of the market], whereas, if you own it all, when slack times come, you could only run a curtailed product.”[7]

Working as a three headed monster, Coleman would act as President, Alfred as Vice President, and Pierre as Treasurer, the cousins could utilize their talents to create a viable enterprise that was diverse throughout the 1910s. However, Pierre DuPont worked to gain control of the entire business when he suddenly bought Coleman’s shares of the company, unbeknownst to Alfred. Alfred sued for breach of trust, but the case was decided in Pierre’s favor. At this point, Pierre would act as President of the company until 1919.[8] Under his tenure in this post, DuPont would incorporate a “modern structure, modern accounting policies, and made the concept on investment primary.”[9] Even without his cousins in the mix, Pierre “transferred a family firm into a giant enterprise and retained family control and influence…believed in systems, was an organization man, always loyal to the family but sentimental about nothing when business judgement was concerned.”[10] After the takeover, DuPont entered into a phase of immense growth as World War I approached. Government contracts and the systematic management made DuPont not only recipients of a lot of work, but also able to deliver on their promises. This, in turn, helped to increase stock prices by almost 500% (share prices would increase from $182 to $772 during this time).[11]

Shortly after the war, Pierre DuPont relinquished his presidency to take over the presidency of General Motors. The experience he had in chemicals and explosives, turned out to be a boon for the automobile manufacturer which had come upon hard times. DuPont and the managers that he brought with him reorganized GM into a “carefully coordinated multidivisional enterprise consisting of autonomous divisions” that would produce many different kinds of vehicles, plus produce “parts and accessories, each with its own production and distribution organization.”[12] Under this management style, the managers would base “production schedules, the hiring of workers, the purchasing of suppliers—even pricing—on annual forecasts.”[13] Utilizing this more scientific method of management, DuPont was able to bring two different companies in two very different industries to become large enterprises that are still forces in the American business world.

Pierre DuPont did not invent the practice of systematic management. However, he was able to utilize what he learned from his family, his education and experience in order to improve the status of two manufacturers that have become leaders in their respective industries. His utilization of scientific methods of management which emphasized the path to the outcome, rather than the outcome itself was extraordinarily effective.

[1] Ernest Dale, “Du Pont: Pioneer in Systematic Management,” Administrative Science Quarterly 2, no. 1 (1957): 28. https://doi.org/10.2307/2390588.

[2] Ibid., 27

[3] Ibid., 30

[4] Rosa Nelly Trevino-Rodreguiez, “From a Family-owned to a Family Controlled Business: Applying Chandler’s Insights to Explain Family Business Transitional Stages,” Journal of Management History. Vol 15, 3, (2009), 284,. https://doi-org.ezproxy.liberty.edu/10.1108/17511340910964144.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism, (London: Harvard University, 1994) Accessed November 14, 2022, 77. ProQuest Ebook Central.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Rosa Nelly Trevino-Rodreguiez, “From a Family-owned to a Family Controlled Business…,” 294.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Earl F. Cheit, “Review of Pierre S. DuPont and the Making of the Modern Corporation,” The Business History Review 46, no. 2 (1972): 255. https://doi.org/10.2307/3113518.

[11] Rosa Nelly Trevino-Rodreguiez, “From a Family-owned to a Family Controlled Business…,” 295.

[12] Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism, 206.

[13] Ibid.

0 notes

Text

Gilded Age: Labor vs. Industrialization

Introduction:

During the Gilded Age, many have striven to prove that the industrialization and urbanization after the Civil War created unprecedented economic growth in the United States. Some have taken the stance that that this growth was made possible at the expense of the laboring classes’ standard of living. However, this conclusion is not totally accurate. While the amount of wealth of the United States did rise significantly (reported as “valuation of property” by the Department of Commerce), the standard of living in among the laboring classes also rose higher than ever. There was a correlation of the laboring classes’ advancement and the rise of the labor movement itself, however, it is unclear if one caused the other to occur or that the labor movement in the late 1800s had any effect at all on workers’ increase in wages or better working conditions overall. Some authors have noted that the consolidation of industry provided lower consumer prices, more efficiency in the supply chain and better financial opportunities for the creation of business itself. The labor movement had many things going against them in terms of an influx of immigration, a technological revolution, and periods of depression during this time.

Research:

In terms of measuring growth, one must look at the data that the US Census reported as an example of the relative expansion of property and manufacturing. From 1860 to 1880, the “valuation” of “property assessed for taxation” was used as a barometer of determining wealth in the US. Upon initial investigation, the total “wealth” of the United States almost doubled in the 10 years between 1860 and 1870 from a valuation of 16 billion to over 30 billion dollars. Using this methodology, the US gained another 1/3 of the 1870 value by 1880 with an estimated true value of over 43 billion dollars. The rise in manufacturing capital invested also followed a similar trend same trend over the same time period increasing from just over a billion dollars in capital invested in 1860 to over 2.7 billion invested by 1880.[1] Author Ballard C. Campbell noted that during the time period from 1870 to 1900 that the overall Gross National Product had almost tripled from 7.4 billion dollars to 18.7 billion dollars, with a large growth in manufacturing output.[2] This rapid growth of wealth might lead some to speculate that the benefits of such success could produce an overall level of material comfort and more spending power of consumers who would benefit from higher wages. However, historians point out that this growth in aggregate GNP did not necessarily correlate to a higher standard of living for all, but rather enriched a small population of industrialists and their managers.

Comparison of labor's gains with increase in standard of living:

Coinciding with this huge growth in GNP and property value, Mel van Elteren notes that the Gilded Age was “marked by steadily falling prices, economic recession and depressions, and a working class movement” that was exemplified with the rise of the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor (AFL).[3] These labor unions were known to have some of their fastest growth during the post-bellum United States as they worked for higher wages and shorter work days. The AFL and other labor unions had steady growth in membership throughout the late 1800s having about 467,000 members by 1898 and garnering over 2 million by 1904 (the last real year of significant increase until the 1930s).[4] Likewise, the average workday between 1860 and 1890 decreased slightly by about an hour and wages increase by 50 to 60 percent.[5]

On the surface, the increase in overall monetary value and the “gains” of the labor movement seems to point to a direct correlation. However, upon further investigation, there could be other reasons for this success. As noted by Van Elteren, the labor movement produced the idea of “producerism” in which laborers thought that “the producer deserves the fruits of his or her labor, often expressed in biblical terms, such as ‘the laborer is worthy of his hire.’”[6] From this notion, labor unions expressed that the owners of the means of production were not being fair and that the laboring classes deserved a bigger part of the profits. However, Campbell noted that the American manufacturing sector had the upper hand in negotiations because there was a competition for American manufacturing goods, an drastic increase of cheap, immigrant labor, technological improvements that made some labor less important, advertising and retailing improvements and a decrease in shipping profits due to the consolidation of railroads (especially during recessionary times).[7] These factors were essential in providing for a decrease in the price of consumer goods, raw materials to make manufactured goods and adverting costs which was passed on to the public at large, thus making a larger contribution to the overall higher standard of living of all Americans during the later 19th and early 20th century. Overall, from 1871 to 1900 (1913=100 as a ‘base’ year) the Consumer Price Index dropped from 99 to 79, after a low of 71 in 1894 and 1896.[8] Life expectancy and GNP per capita also drastically increased between 1870 and 1900. The average life expectancy at birth was 42 in 1870 and by 1900 was 47 and the total average wealth produced by each person increased from $531 to $1,011 in the same period.[9] The results show that there was a significant improvement in overall quality of life.

Conclusion:

While it is still easy to recognize the huge income and lifestyle discrepancies of wealthy business owners and managers of the Gilded Age as compared to the rest of the United States, the age-old argument that business leaders only contributed to their own improvement is simplistic. As Niemi notes, the labor movement’s gains in the mid to late 1800s were “modest” compared to the gains in the early to mid-20th century.[10] The aggregate economic gains of the Gilded Age may not have been equally distributed, but they do show an overall improvement in the quality of life of most Americans, regardless of the labor movement itself.

[1] US Department of Commerce, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789-1945: A Supplement to the Statistical Abstract of the United States, (Washington, DC: Bureau of Census, 1949), 12 https://www2.census.gov/prod2/statcomp/documents/HistoricalStatisticsoftheUnitedStates1789-1945.pdf.

[2] Ballard C. Campbell, "Understanding Economic Change in the Gilded Age," Magazine of

History, vol. 13, no. 4, (1999): 17. ProQuest.

[3] Mel van Elteren, "Workers' Control and the Struggles Against "Wage Slavery" in the Gilded

Age and After." The Journal of American Culture 26, no. 2 (2003): 188. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/liberty.edu?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/workers-control-struggles-against-wage-slavery/docview/200653423/se-2.

[4] Albert W. Niemi, Jr., US Economic History, (New York: Houghton Mifflin): 272.

[5] Ibid., 273.

[6] Mel Van Elteren, “Workers’ Control and the Struggles Against “Wage Slavery”…”, 189.

[7] Ballard C. Campbell, "Understanding Economic Change in the Gilded Age,” 17-18.

[8] US Department of Commerce, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789-1945: A Supplement to the Statistical Abstract of the United States, 231.

[9] Ballard C. Campbell, “Understanding Economic Change in the Gilded Age,” 17.

[10] Albert W. Neimi, Jr., US Economic History, 273.

1 note

·

View note