Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

FINAL

INTRODUCTION:

From Frantz Fanon to Robert Stam and Ella Shohat, all of these theorists present revelating works on race, sexuality, class and their implications in media throughout time, as well as their conscious and unconscious manifestations.

Frantz Fanon in “The Negro and Psychopathology,” delves into the psychological impacts of colonialism and stereotyping on black individuals through harmful narratives. Fanon concludes that one must take agency over stereotyping and negative portrayals in order to escape the “neurosis” that comes along with societal norms and expectations. By subverting these arbitrary standards, black individuals will overcome generational oppression.

bell hooks in her work “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” highlights the unique intersectionality of black women that makes them susceptible to multiple forms of oppression through portrayal in the media. She argues that black women are subjected to harmful stereotypes that deny them freedom of expression in popular forms of media. She also introduces the term “oppositional gaze” which refers to the type of spectatorship black women take on when viewing media to subvert expectations and give agency back to these women. It allows black women to critique media in a way that dismantles oppression instead of upholding it.

Audre Lorde’s “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” builds off of Lorde’s previous works on difference and repetition by explaining how it manifests in different ways to continue oppression. In addition, Lorde upholds that women should be aware of intersectionalities of feminism with racism, classism, ageism and heterosexism. Ignoring “difference” but embracing the differences within women is crucial to dismantling oppression.

Finally, Robert Stam and Ella Shohat in their piece “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation,” discusses the portrayals of marginalized communities in film. They delve into “positive” and “negative” portrayals of these groups, as well as historical pushback from these communities. In addition, Stam and Shohat add nuance to the discourse surrounding “stereotypes,” and instead offer up an alternative explanation that film is a culmination of societal perception just as much as it is the creation of the characters themselves.

With all these theorists in mind, I will first describe the commonalities among the works, then discuss the differences each present. Finally, using the HBO series “The Watchmen,” I will explain how each of the theorists would feasibly compliment and discuss two scenes within the television series.

By utilizing the theories of all of these authors, I will explain how “The Watchmen,” particularly their developments of characters like protagonist Angela Abar and her grandfather Will Reeves, as well as Dr. Manhattan are products of portrayals of race, sexuality and gender. In addition the narrative focus of the series serves to emphasize their individual struggles with identity and societal oppression, as well as their actions done in an attempt to subvert them.

SECTION 1–Dominant Culture and Stereotyping as a Means of Oppression:

All of the theorists, from Fanon’s view of the collective unconscious of the black community, to Lorde’s definition of the “master’s tools,” in investigating institutional oppression specifically examine the psychological ripple effect perpetuated by stereotyping. They delve into the social implications of harmful narratives, as well as providing strategies on how to overcome generational, institutional, and social oppression.

Fanon’s work examines how black people are psychologically affected by harmful stereotyping of black individuals in media, specifically stories targeted towards young children. It is this reinforcement, Fanon says, that villainizes the black community through learned racism. Through adulthood, it is seemingly impossible for a black individual to dismantle these stereotypes from the perceptions of people, particularly the “white world, “(111) (1). He explores how colonization and systemic racism impacts the psyche and identity of the colonized. Fanon's work emphasizes the ways in which colonialism and its modern day manifestations in storytelling creates psychological trauma and a learned unconscious sense of inferiority among colonized peoples, also known as the “collective unconscious,” (112) (2). In order to overcome these learned societal expectations put upon black individuals, Fanon writes that through “collective catharsis” of narratives that empower black culture and dismantle colonial thinking, they may begin to feel less pressured to adapt oneself to eurocentric expectations, and overcome generational traumas that shape their actions in a eurocentric society.

hook’s reading also touches on the effects of negative portrayals of black individuals in the media, specifically black women. She argues that black women face a multitudes of harmful stereotyping in media, writing that “When most black people in the United States first had the opportunity to look at film and television, they did so fully aware that mass media was a system of knowledge and power reproducing and maintaining white supremacy, “ (308) (3). Similar to Fanon, hooks states that societal oppression of black people stems from upholding ideals of white supremacy. This in turn leads to limited portrayal of black people onscreen, and leaves black women with even fewer characters to express relatability due to oppression from the white community as well as black men. hooks states the way for black women to regain agency in light of stereotyping onscreen is the “oppositional gaze,” or when black women create new meaning from media to critique and evolve new meaning: “We create alternative texts that are not solely reactions. As critical spectators, black women participate in a broad range of looking relations, contest, resist, revision, interrogate, and invent on multiple levels,” (317) (4).

Lorde critiques stereotyping as a tool of oppression that reduces individuals to narrow, oversimplified categories based on age, race, class, and sex, especially relating to women. She highlights how these stereotypes perpetuate power imbalances and limit people's self-expression and agency. Stereotypes, according to Lorde, are tools used by dominant groups to maintain control and suppress the voices and experiences of marginalized communities. Furthermore, they restrict individuals' abilities to fully express their unique identities and experiences, forcing them into predefined roles that are often dehumanizing and oppressive. Lorde offers up multiple solutions that go against institutional strategies designed to oppress or “the master’s tools,” (112) (5). Lorde advocates for a culture of women that embrace intersectionality and the many differences in womens’ experiences to create interconnectedness. This unity can help dismantle harmful narratives about different types of women and create affinity stemming from diverse experiences.

Stam and Shohat work discusses the negative effects of stereotypes in film, as well as advocating for a nuanced interpretation of stereotypes themselves.The authors discuss how stereotypes through the eurocentric lens can lead to prejudice, discrimination, and cultural misrepresentation. Stereotypical portrayals in media and popular culture contribute to reinforcing biased perceptions and limiting opportunities for nuanced understanding and empathy of marginalized groups despite pushback. Furthermore, stereotypes can contribute to internalized oppression, where individuals from marginalized groups may internalize negative stereotypes about their own identity. Although representation can go a long way to amending previous harmful portrayals, it is discourse, the authors argue, which makes overcoming stereotyping possible. They write “Rather than directly reflecting the real, or even refracting the real, artistic discourse constitutes a refraction of a refraction; that is, a mediated version of an already textualized and "discursivized" socio ideological world. This formulation transcends a naive referential verism without falling into a "hermeneutic nihilism" whereby all texts become nothing more than a meaningless play of signification,” (180) (6). All in all, societal critique of realism and stereotypes in text is the most critical lens in which to dismantle negative portrayals of marginalized communities.

SECTION 2–Emerging Stereotypes, Amending Stereotypes:

Though all the authors write about stereotypes and various ways of dismantling them, each has a vastly different approach in doing so. Each theorists presents a differential view on the role of agency and opposition to oppression institutions

For one, Fanon states that it is through the unlearning of a black individual’s unconscious thoughts and actions of inferiority that the community can overcome societal oppression driven by colonization. Fanon takes an introspective, psychoanalytic approach focused on excavating how racist colonial stereotypes become entrenched in the unconscious of the black community, in order to dismantle their psychological hold and heal one’s diminished sense of self worth. Unlike others, Fanon’s approach focuses on amending the individual’s mindset, rather than shifting the views of others.

In hook’s essay, she also mentions that black women face a unique form of oppression from not only the dominant white culture, but from black men as well. This mention of intersectionality that differs black and white women deviates slightly from Fanon’s “collective unconscious” of the unified experiences of the entire black community. She quotes a previous essay she wrote about her experience viewing black women onscreen: “We laughed with the black men, with the white people. We laughed at this black woman who was not us. And we did not even long to be there on the screen,” (311) (7). As a way to regain agency over portrayal of black women in cinema, hooks advocates for the oppositional gaze which involves black female viewers consciously interrogating the racial and gender biases embedded in mainstream visual culture, rather than passively consuming stereotypical images. She encourages black women to not take the backseat in witnessing their own oppression onscreen, but instead undermine the phallocentric gaze in which men derive visual pleasure from black women. The oppositional gaze empowers black women to resist stereotyping by critically deconstructing objectifying representations.

Lorde argues that the "master’s tools" of racism, sexism, homophobia, and other forms of oppression cannot be used to effectively dismantle those same oppressive systems and ideologies. Honing in on the feminist movement, Lorde rejects the exclusion of women belonging to other marginalized groups, and calls for a unification of women regardless of “difference,” in experience to present a collective, unified voice that uplifts those often left out of academic feminist spaces. “Without community there is no liberation, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between an individual and her oppression. But community must not mean a shedding of our differences, nor the pathetic pretense that these differences do not exist,” (112) (8). Lorde advocates for developing new frameworks, language, and ways of thinking that emerge from and validate the realities of those facing multiple, intersecting oppressions.

Shohat and Stam offer different origins for the emergence of stereotypes themselves, stating that institutional settings and power structures enable stereotyping, beyond just the representations themselves as well as the politics of language use, casting decisions, and audience expectations that shape stereotypical portrayals. The authors offer a more nuanced appraisal of stereotypes because they argue that due to historical development, stereotypes are malleable because they are products of social and economic change. They argue that dismantling stereotypes requires analyzing the broader discursive structures, institutions, and practices that produce and enable stereotypical representations, not just changing the representations themselves.

SECTION 3:

Episode 6: “This Extraordinary Being”

In episode 6, Will Reeve’s, Angela’s grandfather, takes on the persona of “Hooded Justice” to anonymously fight white supremacists due to the discrimination he faces in the police force. The scene takes place in Will and June’s apartment (Kassell, 0:23:37). After will puts on his signature hood and noose outfit, June puts white makeup on the part of his face where his eyes are exposed. She tells him the reason is ““You're gonna get it with that hood. And if you want to stay a hero, townsfolk gonna need to think one of their own's under it.”

Fanon’s reaction to this scene applies directly to his theory of the collective unconscious among the black community. Due to learned colonial idealizations, Will and June believe that the only way to gain validity in white society is by masquerading as a white person. Because Fanon writes black people are demonized from a very early age, he would uphold that Will and June are using the white makeup as a defense mechanism of safety due their shared experiences with trauma. This would be a correct assumption, as Reeves previously was almost lynched by his fellow police officers for attempting to arrest a man with alleged KKK affilliations.

hook’s interpretation would hone in on the transition from Reeve’s reflection of the white face point, to Angela’s reflection as she experiences the transformation simultaneously due to the nostalgia drugs she takes. hooks would highlight the use of the oppositional gaze in portraying Angela in the footsteps of her grandfather. Not only does the fight to end societal and institutional oppression transcend generations, but by portraying Angela in the reflection of a superhero, she takes agency over her own life’s purpose and inserts herself into this new interpretation of reality. This ties in with hook’s argument that deriving new meaning and critiquing media dismantles oppression and opens up alternative means for interpretation.

Lorde was deeply critical of systems of oppression, including racism and white supremacy. The scene portrays Will Reeves, a black man, having to conceal his racial identity by adopting a white persona in order to operate as a superhero and fight injustice, in other words, using the master’s tools. From this lens, she may have critiqued the scene as reinforcing the idea that black identity and empowerment must be suppressed or hidden within a white supremacist framework in order to be deemed heroic or acceptable. At the same time, the scene highlights Reeves' subversive use of the "Hooded Justice" guise to resist racist systems and fight for justice, which Lorde may have seen as an act of resistance against oppression, albeit one constrained by the limitations imposed by a racist society.

Shohat and Stam would highlight the fact that Reeve’s is conforming to the eurocentric standard of whiteness to be seen as heroic to white society. However, because their belief is that stereotypes are an ever changing product of time and development, the authors would argue that the discourse surrounding this scene would result in a positive notion that June and Will, as a result of the limiting society they lived in at the time, used the mask of a white person as a symbol of resistance and silent irony against the white people who use institutionalized law and social discrimination to oppress them. Ultimately, while the scene could be interpreted as a powerful commentary on the insidious nature of racism.

Episode 8: “A God Walks into Abar”

Dr. Manhattan tells Angela in the bar previously that she will concoct a great idea to hide his true identity so that they can be together. The scene finally comes to fruition in the morgue (Kassell, 0:42:53), where Angela sorts through a multitude of dead bodies to construct Dr. Manhattan’s new identity. Finally, Angela uncovers the body of Calvin, a construction worker that died in Saigon. She picks the final one for Dr. Manhattan’s transformation, and he assumes this person as his own. Angela looks at him in his new form, and embraces him with hope and relief.

Frantz Fanon’s analysis of the scene would specifically hone in on the choice of bodies for Dr. Manhattan’s transformation. Angela noticeably is hesitant to select Calvin’s body in the wake of the other men (white). Fanon would cite this reasoning as a manifestation of the “collective unconscious” of black individuals. He would argue that Angela is internally grappling with whether to deny her own desires and identity to be accepted within colonial culture, and wonders if she should pick a white male for Dr. Manhattan to appear as because she has an unconscious inferiority complex in proximity to whiteness.

Building off of that note, hooks would likely applaud Angela’s agency in choosing the representation of Doctor Manhattan. By picking out a visual identity for Doctor Manhattan, and being satisfied with the results, Angela uses the oppositional gaze to define her own representation of reality. Instead of passively accepting her role in Doctor Manhattan’s life, she redefines her portrayal of him in a physical manner, restating her agency and taking the reins on her own personal comfort level.

Lorde on the other hand would critique Angela’s behavior. She would likely state that by using the “master’s tools,” to change Dr. Manhattan’s appearance to make him presentable for society, she is actively using the tools of oppression to perpetuate the ideals of dominant white culture. In addition, she would critique how Angela, as a black woman, is forced to accept and internalize this stereotypical, inauthentic depiction of black masculinity in order to have a relationship with Dr. Manhattan. In essence, through Lorde's intersectional feminist lens, this scene exemplifies how oppressive racial and gender hierarchies remain deeply entrenched, with the powerful white male perspective still dictating how black identities are represented and consumed, even in seemingly progressive narratives.

Shohat and Stam would likely scrutinize the overall decision making process behind superhero narratives that allow for a white male character like Dr. Manhattan to simply "put on" a black persona as a form of masquerade or performance. They would emphasize how this scene exemplifies the politics of casting decisions and the white male gaze dictating representations of blackness, rather than amplifying authentic black voices and perspectives. Although they would likely critique this aspect, they would probably have a more nuanced view and conclude that this scene cannot be viewed in isolation, but emerges from and reinforces larger discursive structures of racism, stereotyping and objectification of black people.

Conclusion:

In my analysis of the theorists, synthesized with “Watchmen”, it can be concluded that stereotypes are a product of dominant oppression, internalized oppression and the ever changing political climate of society. Due to the complex nature of their emergence, there is no one way to fully dismantle them. Some methods may be tied to the individual, while others have to do with accepting differences in lived experience. Dismantling oppression through years of conditioning and unconscious bias is no easy task, but consuming media through a critical, agency-driven lens is crucial to being able to recognize oppression when it occurs.

Bibliography

Fanon, Frantz. "The Negro and Psychopathology." In Black Skin, White Masks, 141-209. New York: Grove Press, 1967. Pg. 111.

Fanon, pg. 112.

hooks, bell. "Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators." In Black Looks: Race and Representation, 115-131. Boston: South End Press, 1992. Pg. 308.

hooks, pg. 317.

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference." In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press, 1984. Pg. 112

Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation." In Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media, edited by Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, 277-309. London: Routledge, 1994, pg. 180.

hooks, pg. 311.

Lorde, pg. 112

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

Analytical Application #6

Race and Representation

Orientalist Theory

Orientalist theory refers to the distinction made between the orient and the occident, which is more often than not a use of power structure and dynamics to make the orient seem inferior or exotic to its western counterpart. In the video clip titled “The Siamese Cat Song” from Lady and the Tramp, two siamese cats are featured singing about their ambitions to hunt and kill the other pets in the house such as the fish and the parrot. There are important details in this clip that make distinctions between the “west” and “east”, according to Said’s theory. The cats have slanted eyes and slink in perfect unison around the environment mischievously while singing “we are Siamese if you please,” and so forth. This causes shock and apprehension from Lady, the dog, who has doe-eyes standing guard of the other pets in the home. This depiction can be interpreted as a direct demonstration of how the “Occident” views the “Orient” with intrigue and apprehension. The distinctions made between the cats, with the way they walk and smirk perfectly simultaneously, and the dog who perceives them as exotic and threatening applies directly to Said’s argument of how power dynamics between the west and east exist. Specifically, how the west uses harmful portrayals of easterners to solidify their control over social norms. Orientalism, in this context, is used to differentiate the known from the mysterious and exotic unknown by assigning fantastical mannerisms and troublesome actions to the characters. The validity of these portrayals are not questioned, according to Said, stating “Because this tendency is right at the center of Orientalist theory, practice, and values found in the West, the sense of Western power over the Orient is taken for granted as having the status of scientific truth,” (54) (1). These limiting interpretations of the east are accepted as common throughout the region, as further perpetuated by the unison of the cat’s movements, because the west holds the belief they as a society are superior.

Stereotype

A stereotype, often portrayed in television and film, is an expectation or assumption placed upon a group of people and typically a simplified version of the complex reality of this group of people. In Peter Pan, a song called “What Makes the Red Man Red,” showcases Native Americans through stereotypical behaviors and characteristics associated with the group such as a red face, smoking tobacco, and broken english. Throughout the song, Peter and company gawk at the Native Americans, mocking their seriousness and affinity for tribal traditions. The stereotyping of indigenous culture paints this group as a monolith, lacking depth and historical accuracy in dress and tradition. These stereotypes are reminiscent of colonialism in the Americas, upholding the structures of power that suggest that Europeans are superior to others. Shohat comments on this commonality in media stating “Europeans and Euro-Americans have played the dominant role, relegating non-Europeans to supporting roles and the status of extras,” (189) (2). By simplifying a group of people down to idealizations upheld by the eurocentric lens, the Native Americans in this setting are nothing more than a source of entertainment to the white protagonists as an advancement of the plot.

Cultural Dominant

The cultural dominant, according to Stuart Hall, is the set of ideologies perpetuated by media that portray the biases, viewpoints and political positions of those dominant in the social order. Stuart Hall, in his theory of encoding and decoding, states that audiences do not passively encode these messages, and people, especially those in marginalized groups actively reject or reinterpret specific codes. All in all, Hall’s interpretation of the cultural dominant means taking an active role in processing popular media and challenging the messaging that is pushed through it. During the song in Dumbo “When I See an Elephant Fly,” numerous portrayals and messaging relating to politics around African Americans are present. For one, the song is performed by a group of crows who speak in stereotypical African American dialect and use jive-like speech patterns. This plays into racist stereotypes prevalent at the time, with the lead crow named "Jim Crow" after the laws enforcing racial segregation. Since the film was released in 1941, this portrayal relates to political messaging at the time, with the dominant white culture pushing for racial segregation in Jim Crow laws. Although this portrayal of African Americans upholds racist sentiments from the time, Hall writes that it is the job of viewers to interact with media and subvert expectations put onto politically charged characters such as the crows in Dumbo. By recognizing the societal and political implications behind the crow’s portrayal in the movie, viewers take a stance of resistance against it and offer up multiple implications looking past the character.

Eurocentrism

According to Ella Shohat, Eurocentrism is not simply a synonym for "European", but rather a way of viewing the world from a European perspective that is often linked to European colonization of other parts of the world. Eurocentrism even goes so far as to justify systems of power that oppress marginalized groups, labeling it as progress. In the case of “Everybody Wants to be a Cat” in Aristocats, eurocentrism idealizes being a European. By making European culture seem desirable, this ideal actively upholds the systems of eurocentrism that makes the “west” look superior. Throughout the clip, a jazzy tune upholds the sentiments of the cats singing “everybody wants to be a cat,”. However, the differences among the cats present distinct musical breaks that invoke a different reaction depending on the cat. The siamese cat is once again portrayed as a monolith of the east. The cat plays the piano with chopsticks, lyricising about stereotypical things of the east such as “fortune cookies,”. The tune awkwardly cuts in to the song, and does not incite a positive reaction from the other cats. On the other hand, the harp solo from the white female cat incites wonder and awe from the audience, presenting a romantic tune that blends into the rest of the song. These solos present distinct differences because eurocentrism upholds the sentiment that European culture norms “fit” and are viewed as desirable, while cultural “others” do not fit nicely into European society, and shouldn’t be given attention. Shohat and Stam comment on this “othering” by stating “Third World and minoritarian people, it is implied, are incapable of speaking for themselves. Unworthy of stardom either in the movies or in political life, they need a go-between in the struggle for emancipation,” (205) (4). This passage implies that cultural others do not fit into “civilized” society and do not have the same agency or expression that the dominant European culture is entitled to.

Essentialism

Essentialism is the tendency to view cultures, identities, and social groups as having a fixed, unchanging essence. Shohat and Stam write that this is problematic because this ideology ignores the complex and ever diversifying nature of identity and culture. These identities are not stagnant, they are a constantly evolving group of individuals. The song features the character King Louie, an orangutan who wants to be human and learn the secret of fire from Mowgli. This plays into essentialist notions of a fixed, unchanging "essence" of humanity that Louie desires to emulate. However, Shohat and Stam argue that identities are not fixed essences, but rather are "relational, conjunctural, discursive and constantly shifting. Louie's desire to be human ignores the transitory and fluid nature of identity. Shohat and Stam add that “it ignores the historical instability of the stereotype and even of language,” (199) (5). The lyricism in the song adds to this sentiment, implying that King Louie has the closest proximity to being a human, and therefore is superior in the animal hierarchy. By placing these animals into boxes, reminiscent of human society, this clip illuminates the absurdity of placing humans into separate categories. Animals may be fundamentally different among species, but humans are all of the same kind and in theory should make them immune to arbitrary social hierarchy based on outward appearance. People are not stereotypical like animals are, humans are a culmination of societal advancement and ever changing history.

@theuncannyprofessoro

Bibliography

Said, Edward W.. "The Scope of Orientalism" in Orientalism, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1978, pg. 54.

Shohat, Ella and Stam, Robert. "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation" in Unthinking Eurocentrism, London: Routledge, 1994, pg. 189.

Hall, Stuart. "What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?" In Black Popular Culture: A Project by Michele Wallace, edited by Gina Dent, 21-33. Seattle: Bay Press, 1992.

Shohat and Stam, pg. 205.

Shohat and Stam, pg. 199.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Said, Shohat and Stam all critically look at representations of race in media, and how cultural misrepresentation can create harmful perceptions and monolithic beliefs. Shohat and Stam examine further how this medium can also dismantle previous stereotyping.

According to Said in his work “Orientalism”, “Television, the films, and all the media's resources have forced information into more and more standardized molds,” (34) (1). Due to television’s formulaic nature, Said argues that media contributes to homogenizing and stereotyping representations of the Orient. The “orient” is a combination of rich and diverse culture across Asia, with distinct differences among countries and regions. However, in film and television, the Orient’s culture is portrayed as a monolith of exocitized and overdone stereotypes. Because of this lack of differentiation, film and television demonize this group of people and transform them into a cultural other, subjecting them to limited and negative representations of themselves. Because the orient is seen through a European lens in film and television, the nuances of the mixing pot of culture is not expanded upon, instead, elements are taken to be seen as fantastical yet primitive to the technologically advanced west. All in all, orientalism in film depicts the East as a monolith, riddled with cultural stereotypes emphasizing “exocitism” that contributes to othering of these communities.

While Said critique’s the west’s limited portrayal of the Orient, Shohat and Stam offer multiple ways to rise above stereotyping in media. Shohat and Stam in their piece “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation” argue that stereotypes in film provide limiting, almost laughable representations of marginalized communities in film and television. For instance “Latin American audiences laughed at Hollywood's know-nothing portrayals of them off the screen, finding it impossible to take such misinformed images seriously,” (182) (2). Although oftentimes these representations of marginalized communities in film are so surface level they seem comical, oftentimes they can be harmful off the screen. Stereotypes in film are meant to put marginalized communities in boxes to advance the plot dominated by their white, European counterparts. On the other hand, representations of realism may seem like the solution to correcting stereotypes. However, Shohat and Stam mention that “Spectators (and critics) are invested in realism because they are invested in the idea of truth, and reserve the right to confront a film with their own personal and c~ltural knowledge. No deconstructionist fervor should induce us to surrender the right to find certain films sociologically false or ideologically pernicious, to see Birth of a Nation (1915), for example, as an "objectively" racist film,” (178) (3). Although realism could be interpreted as the most optimal due to the lack of imagination presented that could perpetuate stereotypes, the alternative could be harmful such as representations of racism. There is a healthy balance between positive representation and realism in film. However, the audience can truly take agency by critiquing and critically viewing film, as even realism may contribute to further demonization of marginalized communities.

Bibliography

Said, Edward W.. "The Scope of Orientalism" in Orientalism, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1978, pg. 34.

Shohat, Ella and Stam, Robert. "Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation" in Unthinking Eurocentrism, London: Routledge, 1994, pg. 182.

Shohat and Stam, pg. 178.

Reading Notes 10: Said to Shohat and Stam

To wrap up our studies of visual analysis, Edward W. Said’s “Orientalism” and Ella Shohat and Robert Stam’s “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation” provide critical paths to understanding the roles of race and representation play in our production and consumption of film, television, and popular culture.

How is orientalism linked to film, television, and popular media, and in what ways has standardization and cultural stereotyping intensified academic and imaginative demonology of “the mysterious Orient” in these mediums?

What role do stereotypes play in the representation of people, and in what ways can film and television change the perception of cultural misrepresentation?

@theuncannyprofessoro

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Representation in media can greatly impact perceptions of marginalized groups. Both Halberstan and Hall discuss the power dynamics at play between limiting and stereotypical portrayals, as well as ways to dismantle and challenge these ideas.

According to Halberstam, positive images of marginalized peoples in film and television can often be harmful because they portray a limited and narrow view of these communities. In their work “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film”, they argue that in the case of Butches of races other than white “The image of the black or Latina butch may all too easily resonate with racial stereotyping in which white forms of femininity occupy a cultural norm and nonwhite femininities are measured as excessive or inadequate in relation to that norm,” (180) (1). Halberstam concludes that intersectionality between sexual orientation and race on screen often attempt to portray stereotypes while not engaging in conversation on how that may be received. Positive images portray certain stereotypes which can be harmful, especially to minority communities, as they illustrate this entire community as a monolith. Looking specifically into sapphism and sexuality, white women are often portrayed at the forefront of sapphic love. Due to harmful depictions of the degradation of black women throughout history, this display of sexuality is not explored and celebrated the same way that white women are. Although the integration of black and latina butches is a progressive stride in film and television, their portrayls are often limiting and one dimensional, riddled with racial tropes in contrast to white depictions of butches.

Stuart Hall in his essay titled “What is ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?”, he explores how popular culture serves as a multi-faceted platform riddled with political messaging in reference to identity. Cultural strategies play a crucial role in challenging systems of power in the form of stereotyping by creating counter representations. Marginalized groups can assert agency through their challenge of dominant conversations that depict harmful portrayals. Hall says that the path to agency over representation is to accept that popular culture is “an arena that is profoundly mythic,” (477) (2). Similar to the concept of gender performance, the popular culture arena is filled with arbitrary roles to fill of made up concepts of people. By recognizing this fact, marginalized communities can unite to create media that is representative of their community as a whole. Cultural production can serve as a tool for building solidarity and fostering cohesive action.

All in all, conceited efforts towards dispelling the “myths” of stereotypical characteristics is a progressive way to strive for equal and diverse representation of all individuals.

Bibliography

Halberstam, Jack. "Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film." In The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, edited by Henry Abelove, Michele Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin, 237-249. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993, pg. 180.

Hall, Stuart. "What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?" In Black Popular Culture: A Project by Michele Wallace, edited by Gina Dent, 21-33. Seattle: Bay Press, 1992, pg. 477.

Reading Notes 9: Halberstam to Hall

Jack Halberstam’s “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film” and Stuart Hall’s “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” link our inquiries into gender and sexuality with race and representation.

What examples of “positive images” of marginalized peoples are in film and television, and how can these “positive images” be damaging to and for marginalized communities?

In what ways is (popular/visual) culture (performance) a complicated and political site where various identities are negotiated, and how can cultural strategies make a difference and shift dispositions of power?

@theuncannyprofessoro

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analytcal Application #5

Male gaze:

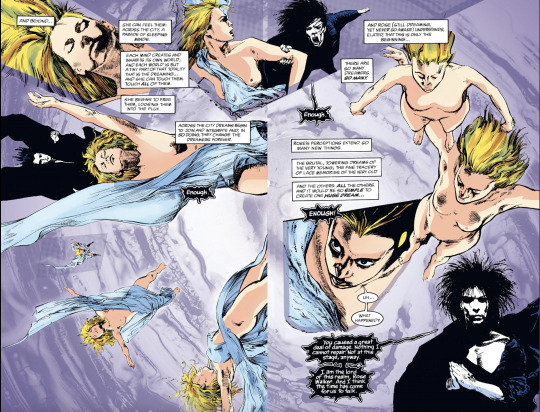

The concept of the "male gaze" was coined by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey. It refers to the perspective in which visual media, particularly film, is often constructed from a heterosexual male point of view. This male gaze objectifies and sexualizes women, positioning them as passive objects for the pleasure and consumption of the male viewer. Rather than being depicted as fully realized human beings, women in media under the male gaze are reduced to their physical attributes and presented solely for the visual gratification of the presumed male spectator. In the case of this panel in Sandman (page 408), one of the female characters, Rose, appears mostly nude, falling from the sky, being covered by nothing but a cloth. Upon reading the panels and the surrounding storyline, there is no clear reason for this depiction of Rose and her fall from grace. This panel contributes to the male gaze through the objectification of Rose, and the sexualization of her body for aesthetic pleasure. In addition, there are many stills captured of her as she falls with no clear reason other than to emphasize her nudity in this scene. In the eyes of Mulvey, this depiction means “their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness,” (715) (1). Rose’s role in this panel is purely exhibitionary, and neither adds to her character development in the story nor gives her depth beyond a display captured in her multiple nude illustrations.

Scopophilia:

The concept of scopophilia refers to the pleasure and power dynamics inherent in the act of looking and being looked at, often associated with voyeurism in visual media.

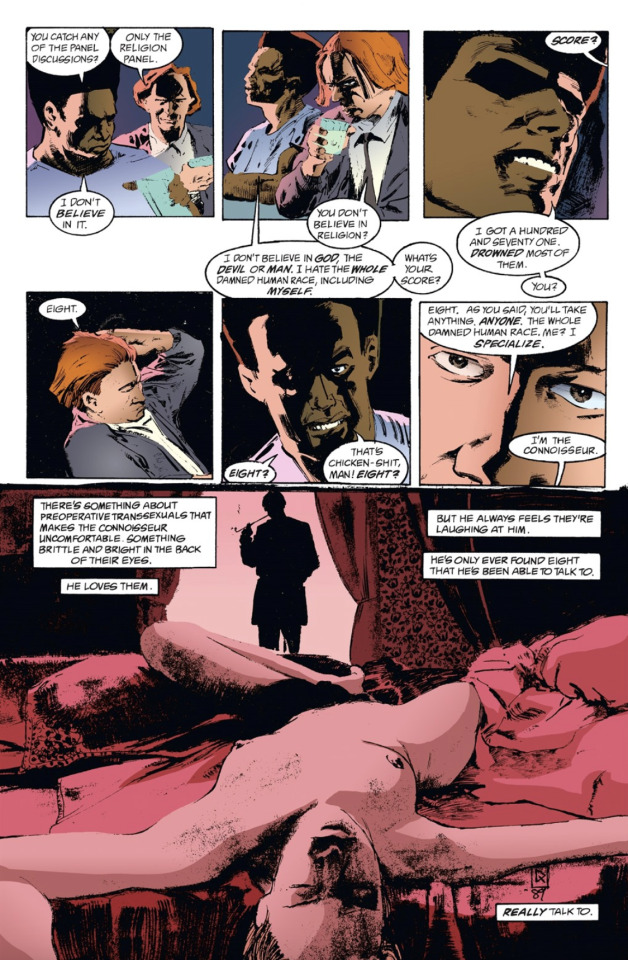

This term encompasses both the desire to view others, as well as the desire to be seen and visually consumed. It reflects the power dynamics at play, where the viewer holds a position of authority and control over the object of their gaze. This concept is shaped by cultural norms and expectations surrounding visibility, surveillance, and the objectification of the human body. In this particular panel, a woman is seen splayed out naked on a bed, seemingly in a sexual context. The text elaborates on this panel, with a man describing fetishization of trans women. This connects back to Mulvey’s explanation of scopophilia, explaining that it “exists as drive quite independently of the erotogenic zones.' It is about 'taking people as objects, [and] subjecting them to a controlling and curious gaze," (713) (2). Using Mulvey’s theory, this panel reduces the woman as a commodity to be looked at, fetishized, and to derive pleasure from. Examining the dialogue as well, the woman lacks her own agency, being talked about entirely in the third person, in reference to how she can be used for the pleasure of the man. In addition, the man capturing the woman as the center of his focus emphasizes the box he places the woman into as something exotic, quoting “There's something about preoperative transsexuals that makes the connoisseur uncomfortable. Something brittle and bright in the back of their eyes. He loves them”. This description of the woman emphasizes the voyeuristic view of both the man’s words and actions, but the objectification of the drawing of the woman as well. Her sole purpose is to be looked at, observed and to create pleasure.

Mythical Norm:

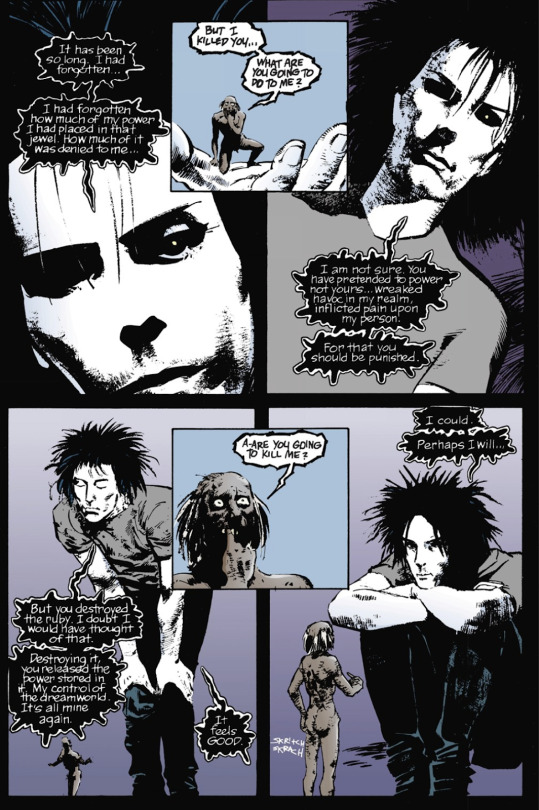

The term mythical norm was widely developed by Audre Lorde, describing the dominant societal standards that are often based on a narrow, idealized image of a "normal" individual or group, typically white, heterosexual, and male. This norm marginalizes and excludes those who do not conform to it. The mythical norm in the context of Sandman manifests into the portrayal of mythical beings who hold significant power. In particular, the Sandman himself is a representation of a mythical idea with its physical form taking the appearance of a heterosexual white male. On page 195 of the comic, the Sandman’s physical power is exhibited in scale. All in all, the character Sandman upholds the common trope that mythical manifestations of power in the mortal world, those having to do with dreams, deception, prosperity a majority of the time appear in the human form of male. Lord comments that mythical norms are “the trappings of power reside within this society. Those of us who stand outside that power often identify one way in which we are different, and we assume that to be the primary cause of all oppression forgetting other distortions around difference…” (116) (3). Mythical norms affect viewership in the sense that when people in positions of power in media are depicted solely as white heterosexual males, this lack of diversity manifests into insecurity in real life. People don’t see themselves in high positions of power because artificial recreations of power structure uphold the power structure in real life. The Sandman upholds the repeated idea that white heterosexual men are the pinnacle of power in society.

Oppositional Gaze:

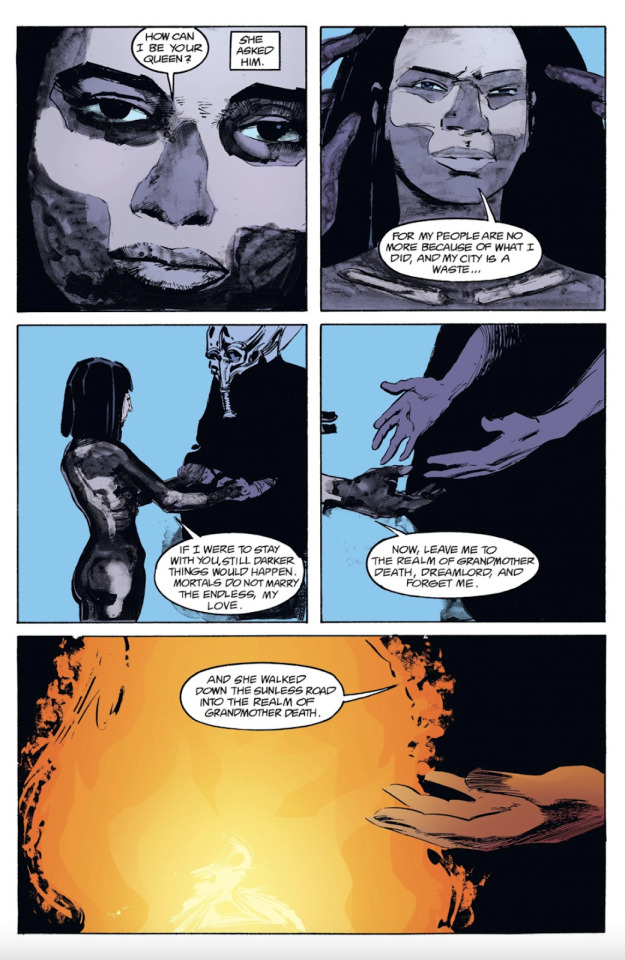

The oppositional gaze refers to a type of viewership described by bell hooks as the phenomenon where “Black female spectators actively chose not to identify with the film's imaginary subject because such identification was disenabling,” (313) (4). This essentially describes the rebellion of the viewership of black women from choosing not to identify with the film's imaginary subject because such identification was so at odds with their lived experience. Applying this viewership to an analysis of Sandman, the mini story within the comic titled “Tales in the Sand,” where Nada, the queen of a land falls in love with the god of dreams, and kills herself to avoid being his queen. She initially refuses to marry a man and rules her kingdom solely. However, she encounters a stranger and goes to great lengths to find him. When she discovers he is an immortal god, she refuses to be with him and runs away while Kai'Ckul pursues her. She kills herself after her kingdom is destroyed by the sun. She is chased in the afterlife while still refusing to join Kai’Ckul’s kingdom. This story refers to the oppositional gaze from multiple angles of the story. Nada, a woman of color, maintains her agency throughout the story from refusing to marry a man for the sake of validity, and choosing her own destiny without needing a man. Nada subverts classic tropes of femininity and is the protagonist of her own story. She is also depicted as a woman in power, despite her facing oppression from a man in power above her. This is significant, however, because she refuses to concede to the whims of a man, and sacrifices herself as an act of rebellion, maintaining her ideals in the end.

Gender Norms:

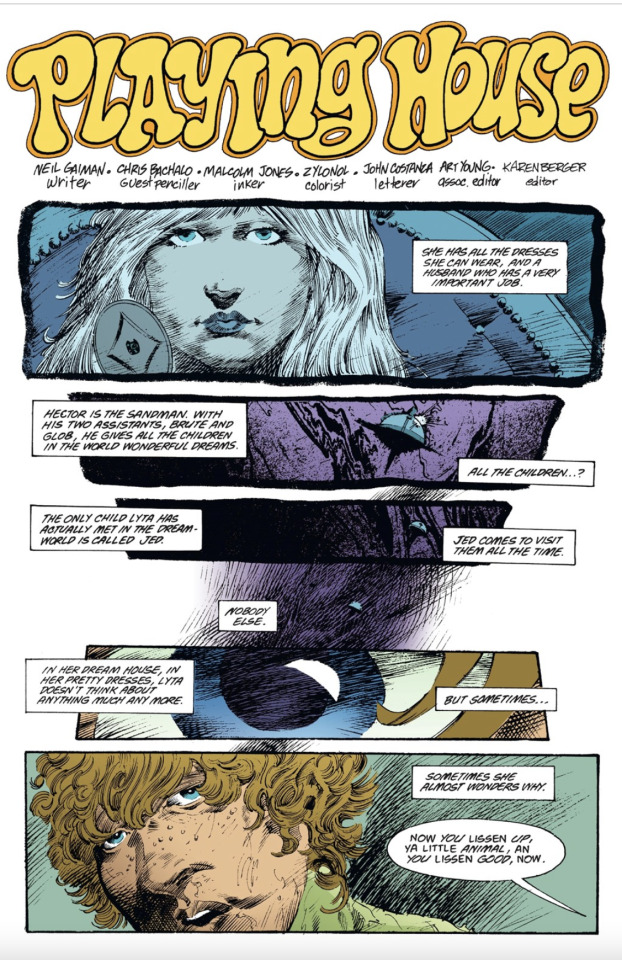

Gender norms are arbitrary societal expectations and standards regarding behaviors, roles, and attributes considered appropriate for individuals based on their perceived gender. These norms often reinforce traditional binary understandings of gender and may condemn alternate expressions that deviate from these norms. In another miniature story in the comic titled “Playing House”, Litya grapples with feeling unfulfilled by the traditional life she leads. She feels a loss of control over her life because she lacks freedom to pursue the dreams she left behind for her husband. Eventually, Sandman kills her husband for pretending to be him, and tells Lidya she should be grateful because she now has the freedom to pursue her own life. It is at this point where she realizes two things: she was living in a dream for years of the “perfect life”, and she was done letting men control her life and make decisions for her. This story subverts gender norms by showing that the idea of “playing house” doesn’t lead to satisfaction, it leads into a constant haze of unfulfilled desires and superficial happiness. Although Litya thought the perfect life was quote “mommy, daddy and a kid,” she actually leads a life of constant sadness and feeling like she is taking the backseat to her own livelihood. She plays a character, and in turn leads a pretend life, like a “dream”, in Lidya’s words. Judith Butler emphasizes that gender norms are essentially a “drag performance”, quoting “'imitation' is at the heart of the heterosexual project and its gender binarisms, that drag is not a secondary imitation that presupposes a prior and original gender, but that hegemonic heterosexuality is itself a constant and repeated effort to imitate its own idealizations,” (338) (5). Gender as a performance is a repeated act to uphold previous reproductions of norms implemented in society. Lidya feels unfulfilled in her seemingly perfect life because she is living a life of fantastical acts of what she thinks is appropriate for her gender.

Bibliography

(1) Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), pg. 715.

(2) Mulvey, pg. 713

(3) Lorde, Audre. "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House." Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Crossing Press, 2007, pg. 116.

(4) bell hooks, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory (New York: New York University Press, 1999), pg. 313.

(5) Butler, Judith. "Gender Is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion." Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of "Sex", Routledge, 1993, pg. 338.

@theuncannyprofessoro

1 note

·

View note

Text

In their respective works, Audre Lorde and Judith Butler delve into the intricate interplay of power, privilege, oppression and the construction of gender identities. Lorde astutely critiques the limitations of existing power structures, while Lorde advocates for seeking alternative frameworks that challenge deeply rooted power dynamics.

Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” explores complexities of power, privilege, oppression, and marginalization. She refers to systems of power as “the master’s tools,” to illustrate how they cannot effectively address or dismantle the systems of oppression they have thus created. This is due to the fact that these “tools” are inherently biased and upheld by existing power structures. This also comes into play when trying to dismantle societal issues that involve multiple intersectionalities of people. For instance, many ideals of the feminist movement are solely based on the white feminine experience. Audre Lord quotes this is harmful because “If white american feminist theory need not deal wit the differences between us, and the resulting difference in our oppressions, then how do you deal with the fact that the women who clean your houses and tend to your children…are, for the most part, poor women and women of color,” (112) (1). One’s own experiences determine the baseline for political change. Meaning that cultural, marginal differences create varying solutions to these problems. Lorde suggests that in order to address oppression and marginalization, we must first acknowledge and examine the ways in which power and privilege operate in society. One cannot solely rely on oppressive systems to address oppression. Instead, alternative frameworks and perspectives must be sought out that challenge existing power structures.

2. According to Judith Butler’s piece “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion”, the concept of gender and gender affirming practices are entirely synthetic and developed/manifested throughout centuries of conditioning. Cultural, societal, and media representations reinforce and perpetuate certain gender norms and expectations by continuously depicting specific behaviors, appearances, and roles associated with masculinity and femininity. These depictions present gender as a binary, perpetuating the idea that there are fixed “roles” for male and female identities. Heterosexuality is essentially a performance to Butler because it is not a natural or innate orientation but rather a social construct enacted and “performed” through behaviors, gestures and discourse. “...drag is subversive to the extent that it reflects on the imitative structure by which hegemonic gender is itself produced and disputes heterosexuality’s claim on naturalness and originality,” (339) (2). Butler uses the example of drag, something associated with a “performance”, to apply the same characteristics of acting to that of being heterosexual. She argues that heterosexuality is a mixed performance of actions to adhere to the characteristics associated with this norm.

Together, Lorde and Butler’s insights shed light on the complexities of power, privilege, and gender performativity, urging critical reflection and action to challenge these systems of oppression.

Bibliography

Lorde, Audre. "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House." Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Crossing Press, 2007, pg. 112.

Butler, Judith. "Gender Is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion." Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of "Sex", Routledge, 1993, pg. 339.

Reading Notes 8: Lorde to Butler

In our continued discussions, Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” and “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” and Judith Butler’s Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” provide further introspection into systems and definitions of gender and sexuality.

How do power and privilege impact the relations people have with each other and with institutions, and how can we acknowledge, examine, and remedy oppression and marginalization using oppressive and marginalized systems?

How do cultural, societal, and media representations support gender performativity and in so doing complicate gender norms, and in what ways is heterosexuality a performance?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Notes 8: Lorde to Butler

In our continued discussions, Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” and “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” and Judith Butler’s Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” provide further introspection into systems and definitions of gender and sexuality.

How do power and privilege impact the relations people have with each other and with institutions, and how can we acknowledge, examine, and remedy oppression and marginalization using oppressive and marginalized systems?

How do cultural, societal, and media representations support gender performativity and in so doing complicate gender norms, and in what ways is heterosexuality a performance?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Both Mulvey and Hooks engage in discourse in regards to the semiotics of film viewership. They both contribute ideas that suggest there are broader social constructs such as race, sexuality and gender that affect our perceptions and reactions to formulaic film.

How does the spectacle of the female image relate to patriarchal ideology, and in what ways do all viewers, regardless of race or sexuality, take pleasure in films that are designed to satisfy the male gaze?

Starting off with Mulvey, she coins the term ‘male gaze’ as “phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness,” (715) (1). In simple terms, women in film are designed to be eye catching and erotic for their male viewers. They are purely a visual aspect, without putting emphasis on their deeper qualities. She argues that patriarchal ideology permeates mainstream cinema, shaping the way female characters are depicted and positioning them as objects to be looked at and desired by the male protagonist and, by extension, the male audience. As a result, the female appearance is perceived as highly aesthetic. Audiences, regardless of sex or race, idolize the ‘ideal’ woman in film, and these expectations are put on to women in real life. Mulvey suggests that all viewers, regardless of their race or sexuality, are socialized within a patriarchal culture that privileges the male gaze. As such, even viewers who do not identify as heterosexual males are conditioned to derive pleasure from films that cater to the male gaze. This is because mainstream cinema tends to prioritize the male perspective and objectification of female characters, thereby shaping the viewer's understanding of what is considered visually appealing and desirable.

How do racial and sexual differences between viewers inform their experience of viewing pleasure, and in what ways does the oppositional gaze empower viewers?

Hooks argues that stereotypical representations of marginalized communities, specifically black women can perpetuate harmful narratives on to black women off the screen, and create an expectation for black women’s portrayl in film. Hooks uses an example of a representation of a black woman she saw as a child in Amos ‘n’ Andy, stating that “She was even then backdrop, foil. She was bitch-nag. She was there to soften images of black men, to make them seem vulnerable, easygoing, funny, and unthreatening to a white audience. She was there as man in drag, as castrating bitch, as someone to be lied to, someone to be tricked, someone the white and black audience could hate,” (311) (2). Racial and sexual differences can absolutely affect viewership, as white people see themselves diversely represented throughout media. In the case of black women, hatred for this group can come from the intersections of black males and white people. On the other hand, black women being represented in a positive light allows black women, as Hooks states, reclaim their agency and assert their own perspectives and experiences. This empowers marginalized viewers to forge alternative modes of viewing pleasure that challenge dominant power structures and promote greater inclusivity and representation. The oppositional gaze allows marginalized viewers to subvert and critique the hegemonic gaze imposed by mainstream media and to find moments of empowerment and identification within media texts.

Race, gender, and sexuality all play a hand in perception of media. Hooks and Mulvey argue that deep rooted societal issues such as the patriarchy, racism, and marginalization of black women are subconsciously reaffirmed through stereotypical portrayls of women, or black women in media. Hate of these groups can come from outside, or be internalized within ones own gaze. Liberation comes from challenging these typical formulas prolific in media, and attaining a critical lens of these representations.

Bibliography

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), pg. 715.

bell hooks, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory (New York: New York University Press, 1999), pg. 311.

Reading Notes 7: Mulvey to hooks

Shifting our visual analysis and critical inquiries to gender and sexuality, we will begin our explorations with Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” and bell hooks’s “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.”

How does the spectacle of the female image relate to patriarchal ideology, and in what ways do all viewers, regardless of race or sexuality, take pleasure in films that are designed to satisfy the male gaze?

How do racial and sexual differences between viewers inform their experience of viewing pleasure, and in what ways does the oppositional gaze empower viewers?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analytical Application #4: Psychoanalysis and Subjectivity

Term #1: Uncanny

The term “uncanny”, is a term that psychologist Sigmund Freud describes as something that is familiar yet unfamiliar. The five traits he uses to assign to an uncanny experience is unhomeliness, repetition, the presence of a doppelgänger, inanimate objects having animate traits, the return of the repressed, and the ambiguity between reality and fantasy. In the final scene of “Squeeze” from The X Files, Tooms is shown in a slow closeup shot, cutting between his slight grin and a small opening in his prison cell left by the people who put his food through a slot. This leaves the episode in an ambiguous resolution, and creates an intellectual uncertainty with the audience whether Tooms, an alien who can squeeze through tight spaces to attack his victims, has really been caught, or if he makes his escape. According to Freud, the uncanny is “The most remarkable coincidences of desire and fulfillment, the most mysterious recurrence of similar experiences in a particular place or on a particular date, the most deceptive sights and suspicious noises—none of these things will take him in or raise that kind of fear which can be described as ‘a fear of something uncanny’,” (402) (1). The recurrence of a small space that Tooms can squeeze through the episode leaves the audience on shaky ground. What was formerly accepted as a firm resolution, turns into a coincidental lack of attention by the prison guard, and opens up a realm of uncanny possibilities without any confirmation of an ending. A true uncanny event is one that leaves one wondering what the true reality of the situation is. The last scene in this episode is executed well, as there is a suggestion that Tooms may have escaped, but none can be sure of the truth.

Term #2: Heimlich

Another term used by Freud is “heimlich” This translates to “familiar” or “at home”. He notes that heimlich is “Friendly, intimate, homelike; the enjoyment of quiet content, etc., arousing a sense of peaceful pleasure and security as in one within the four walls of his house,” (372) (2). In the scene where Tooms attacks Scully in her apartment, (0:36:27-0:39:05), he sneaks through the vents of her home and attacks her in her bathroom. Scully’s home, or heimlich, is a place of rest, supposedly where she is to feel most safe and comfortable, according to Freud’s theory. Tooms is known for victimizing people by sneaking through the vents or chimney’s of people’s place of work or their personal homes or apartments. By attacking victims in their homes, and sometimes stealing personal effects, a sense of uncanniness is created from Tooms, as he completely shatters the safety bubble of the heimlich. His ability to invade seemingly secure spaces taps into primal fears of invasion and vulnerability. This also creates an aura of unexpectedness, as even though one can create an illusion of safety by locking doors or windows, this character can bypass this layer of security by infiltrating cramped spaces that a normal person wouldn’t. A sense of fear is created when the place or feeling one deems as secure or homelike (heimlich), is forcefully entered and made unsafe. Otherwise known as uncanny, where the familiar becomes the unfamiliar.

Term #3: Disalienation

For Fanon, "disalienation" refers to the process through which individuals, particularly those who have been oppressed or colonized, reclaim their sense of agency, dignity, and humanity. It involves breaking free from the internalized feelings of inferiority, self-doubt, and dependency imposed by colonial structures. Disalienation is about regaining a sense of self-worth, autonomy, and empowerment. Throughout this episode of X-Files, the character Fox Mulder, a part of the FBI’s paranormal activity unit, is repeatedly belittled and ignored because of his unconventional methods of approaching cases. For instance, he asked seemingly unrelated questions during Toom’s lie detector test that made the other agents question his validity. When Scully gets attacked by Tooms in her apartment (0:38:45-0:39:08), Mulder comes to her rescue and handcuffs him. Mulder victoriously comments that he won’t meet his quota this year. It is in this moment that Mulder attains a sense of self-confidence in his ability. It is confirmation that his unconventional methods ended up being a success in catching the killer, regardless of the criticism of the other agents. Franz Fanon explains that the goal of disalienation is to “persuade the group to progress to reflection and mediation,” (141) (3). This scene is a liberating moment for not only Mulder, but the investigative branch of the FBI that has been the subject of jokes and criticism, causing it to fall at the bottom of the hierarchy among FBI agents. By proving this case’s validity, Mulder, Scully, and the other agents in the branch gain a sense of self-confidence in their abilities.

Term #4: Collective Unconscious

The collective unconscious is a term used by Franz Fanon, originally coined by Carl Jung, to describe “an expression of the bad instincts, of the darkness inherent in every ego, of the uncivilized savage,” (144) (4). This term focuses on the subconscious thoughts shared by all human beings, containing universal, inherited, and pre-existing psychological patterns or archetypes. In the brains of all humans, we have expectations of experiences, people, or situations that shape our judgements. In the case of Tooms, his archetype affects the judgements of the FBI agents on his safety. During the polygraph test scene (0:15:02-0:20:09), Tooms is asked a series of questions, as he was previously caught squeezing through a chimney and arrested. After Mulder askes unconventional questions such as “are you 100 years old?”, the other agents Colton and Fuller stop the test. The examiner deems he passed, despite the two questions Mulder asked being deemed lies, and Fuller complains that Tooms was just a civil servant doing his job. Besides lie detector tests not being a reliable measure of someone’s innocence, it’s important to note that Tooms presents as a white male. Using Fanon’s application of the collective unconscious, many people have an unconscious bias of individuals based on their membership to groups. Oftentimes in the justice system, individuals belonging to marginalized groups receive harsher sentencing and treatment when arrested on the basis of a crime. His analysis of the situation, civil servant on paper being caught sneaking up a chimney, checked out in his mind because of his unconscious judgement based on the archetype he created of Tooms. Fuller refused to do further questioning and investigating, leaving Mulder and Scully to do it on their own.

Term #5: Mirror Stage

The mirror stage is a concept employed by Jaques Lacan to describe a human psychological milestone occurring between 6 and 8 months of age where children can recognize themselves in a mirror. Lacan argues that this moment of self-recognition in the mirror is both exhilarating and disconcerting for the infant (78) (5). On one hand, it provides the infant with a sense of mastery and wholeness, as they perceive themselves as a unified and autonomous being separate from the external world. On the other hand, it also creates a sense of alienation and fragmentation, as the infant realizes that the image in the mirror does not fully correspond to their internal experience of themselves. Thinking Broadly in a societal interpretation of the mirror stage, the concept of Tooms and his abilities can be a distorted reflection of the collective fear and anxiety of home invasion. The feeling of never truly being safe no matter where one goes. The opening scene of this episode is a prime example of the threat Tooms presents(0:01:32-0:03:09). After Usher steps out of an elevator within an office building, he witnesses the doors reopening only to find the elevator cabin mysteriously absent. Usher then contacts his wife before departing from his office to grab a cup of coffee. As he exits, a ventilation shaft in his office silently loosens and begins to open. Upon Usher's return to his office, his door is shut, followed by the sounds of a struggle and repeated rattling of the door handle. The commotion ceases suddenly with a loud impact denting the door. As Usher's coffee spills onto the floor and he collapses lifeless, the ventilation shaft is promptly sealed shut once more. After the scene, the FBI agents describe the peculiarity of the murder, including that it took place in a high security building with no one occupying it. Tooms' actions and the fear he instills in others could represent a distorted mirror reflecting societal anxieties about vulnerability, invasion of privacy, and the presence of unseen threats. Just as the mirror stage represents a moment of both recognition and alienation, Tooms' actions in "Squeeze" evoke both a recognition of the primal fear of being hunted or invaded and a sense of alienation from the ordinary, safe world.

Bibliography

Freud, Sigmund The Uncanny” in Collected Papers Volume IV, trans. Joan Riviere (London: The Hogarth Press, 1948) pg. 402.

Freud, pg. 372.

Fritz Fanon, “The Negro And Psychopathology” in Black Skin White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (United Kingdom: Pluto Press, 1986), pg. 141.

Fanon, pg. 144.

Jacques Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function” in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006) pg. 78.

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

The art of delving into the visual experience relies on the individual and nuance perspective of the viewer. One’s experiences or exposure can affect one’s reflection of visual texts.

Freud examines the term uncanny and explains that it is something that is familiar, yet not quite at home. There are a certain number of conditions that fall under Freud’s analysis of the uncanny. This includes “unheimlich,” (370) (1) the term Freud uses to describe the feeling of unhomeliness , repetition, the presence of a doppelgänger, inanimate objects having animate traits, the return of the repressed, and the ambiguity between reality and fantasy. Although not mutually exclusive, one or more of these traits must be present in an uncanny experience or event. When an event doesn’t ressurge the repressed.

Jacques Lacan, sought to reframe Freud’s ideas of psychoanalysis in relation to the development of society and language. He states that neurosis “provide[s] us schooling in the passions of the soul, just as the balance arm of the psychoanalytic scales–when we calculate the angle of its threat to entire communities–provides us with an amortization rate for the passions of the city,” (81) (2). In summary, Lacan argues that the rawest expression of emotion can be a measure of the social climate, and therefore the desires of society. Assessing neurosis gives insight into how emotional experiences affect individuals and society as a whole.

Like previously stated, individual experiences have a great impact on one’s perception and interpretation of media. There is a huge lack of representation of marginalized communities in media. This issue conveys to viewers that these communities are not important, and to marginalized viewers, that their voice does not matter if they cannot see themselves being represented. Continuous lack of representation leads to stereotypes, and a monolith for entire communities are created. This can have disastrous effects on the community. Frantz Fanon explains this by saying, “This collective guilt is borne by what is conventionally called the scapegoat. Now the scapegoat for white society—which is based on myths of progress, civilization, liberalism, education, enlightenment, refinement—will be precisely the force that opposes the expansion and the triumph of these myths. This brutal opposing force is supplied by the Negro,” (150) (3). This issue of prevailing stereotypes stemming from limited portrayals of communities, specifically the black community, creates harmful views from outsiders, but also within. Marginalized communities do not see themselves in certain positions, and they inherit sense of “guilt”, from feeling the need to carry themselves individually as a reflection of their entire community.

Perception plays such an important role in interpretation of visual text, but individual perception can be harmful when there is a continuous story told that is singular. On the other side of the spectrum, individual perspective can be beneficial in terms of social development, or being able to define unique experiences.

Bibliography

Freud, Sigmund The Uncanny” in Collected Papers Volume IV, trans. Joan Riviere (London: The Hogarth Press, 1948) pg. 370.

Jacques Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function” in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006) pg. 81.

Fritz Fanon, “The Negro And Psychopathology” in Black Skin White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (United Kingdom: Pluto Press, 1986), pg. 150.

Reading Notes 6: Freud to Lacan to Fanon

We look to Sigmund Freud’s “The Uncanny,” Jacques Lacan’s “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I,” and Frantz Fanon’s “The Negro and Psychopathology” for our inquiry into the functions of psychoanalysis and subjectivity when examining visual texts.

Why do people call an experience or event uncanny, and what makes an occurrence that appears to be uncanny but is not uncanny?

What is the relation of personal neurosis to social passions?

In what ways are oppressed and marginalized viewers alienated when they are not or rarely represented?

@theuncannyprofessoro

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Benjamin also argues an economic analysis of the material reproduction of art as a means for financial gain, but the destruction of art’s original meaning and aura. He uses the success of the dada movement to explain why their destruction of original work had a profound effect on audiences: “What they intended and achieved was a relentless destruction of the aura of their creations, which they branded as reproductions with the very means of production,” (681) (6). By creating an obscene reproduction of their original art, the dadaists reveal the very “obscenity” of reproduced art in a capitalist society. Capitalism destroys the very significance of art as an irreplaceable artifact that contributes to culture. Benjamin states that the reproduction of an original is not a replacement for the original, and in fact destroys the original significance of the piece. Barthes analyzes various cultural phenomena, such as advertisements, magazines, and popular culture, to uncover the myths and ideologies embedded within them. He employs semiotic analysis to reveal the ways in which these myths naturalize and reinforce dominant social structures and power dynamics. Barthes' work is more focused on the ways in which language and symbols construct meaning in society, and he emphasizes the importance of critical reading and decoding of cultural texts. Although similar to Marx and Engles through his analysis of power dynamics and pop culture, Barthes’ examines it in a broader societal context rather than the relationship between the ruling and working class. “...myth is a system of communication, that it is a message. This allows one to perceive that myth cannot possibly be an object, a concept, or an idea; it is a mode of signification, a form,” (107) (7). Myth is a conversation between signs and the signification they are given throughout. Barthes argues there is a dominant narrative present in myths, but he emphasizes the use of mythology as a societal means to give meaning to the arbitrary sign. Deleuze also mentions the significations of signs through conversations of replication. Deleuze's work is more abstract and philosophical, exploring concepts such as repetition, difference, and becoming. He critiques traditional systems of thought and seeks to develop new frameworks for understanding reality and subjectivity. All in all, his approach is more concerned with ontology, metaphysics, and the nature of thought and perception. Repetition is a means in the abstract to delve deeper into meaning in terms of morals, ethics and law. Throughout organic repetition, Deleuze cites, is where transformation can occur in the meta.

Section 3: “Barbie”, signs as a means for capital gain through mechanical reproduction

The opening scene of "Barbie" sets the stage for a profound exploration of the cultural significance of Barbie dolls, employing various theoretical frameworks to unpack its layers of meaning. From a Marxist perspective, the commercial success of Barbie as a product and the creation of its own mythology can be seen as emblematic of the capitalist system's ability to commodify culture and promote the ideals of the ruling class. The depiction of the dolls as mechanical reproductions of art serves to reinforce this idea, as they are mass-produced objects designed to perpetuate consumer culture and reinforce dominant ideologies.

The transition from the bleak desert scene to the vibrant world of Barbie Land symbolizes a transformation in meaning and significance. Drawing on Roland Barthes' concept of mythology, the contrast between the drab atmosphere of the girls' play area and the colorful world of Barbie dolls highlights the mythic narrative surrounding Barbie's role in offering endless possibilities and empowerment to young girls. By presenting Barbie as a symbol of progress and liberation from traditional gender roles, the film constructs its own mythology that reshapes the signification of signs associated with dolls.

Moreover, Gilles Deleuze's notion of repetition and difference offers insight into the evolving meaning of Barbie dolls. While the old dolls may have served a singular purpose of teaching girls to fulfill traditional motherly duties, Barbie represents a shift towards multiplicity and diversity in representation. Through various careers and identities, Barbie becomes a symbol of imagination and play that transcends narrow gender expectations, echoing Deleuze's exploration of the transformative potential of repetition in creating new meanings and possibilities.

In essence, the opening scene of "Barbie" encapsulates a rich tapestry of cultural, economic, and philosophical themes, inviting viewers to critically engage with the complexities of Barbie's cultural significance and the broader implications of consumer culture and representation.