Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

“How’s your WIP going?”

"Have you made any progress?”

“How close are you to being done?”

73K notes

·

View notes

Text

Not to reinvent the wheel over here but humanity is sooo right about tea. It really is the perfect finnicky little thing to do. You can use it as an excuse to get up and transition to the next thing for yourself or with others; you can use tea as the centerpiece for socializing; you can use it as a meditative device or a comfort ritual or as medicine or to soothe pain or to set intentions or go to bed or to wake up. And most tea is pretty inexpensive, healthy and sometimes you can just harvest the ingredients yourself. And there's a set amount of time it takes to heat up the water and prepare your cup and let it steep, which is all part of a ritual that makes it fast but not instantaneous which is. Good.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

That's a 2,500 year old mosaic floor from Pompeii. The cord across the entryway, the text in the display on the wall, these things make me think that once upon a time they used to let you walk on that floor. Which is wild.

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

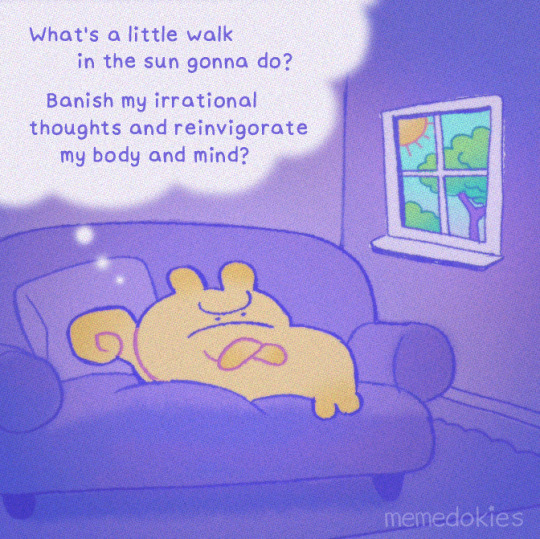

every time i go outside i am astounded by the power of sun and air

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Rewatching Apothecary Diaries and remembering how much I love these dorks

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

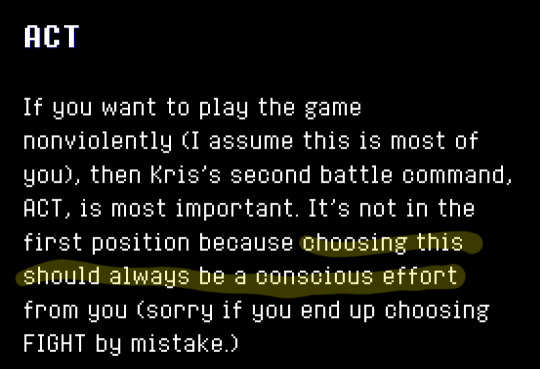

I’ve had this idea for forever, and only now finally had the time to do it 😮💨

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

kitties in watercolours from January, which I wasn't able to properly scan until now :')

{art print}

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

One scene that i really adored throughout the series

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

For all of the northerners that stood up for Texas during our freeze and said, "Don't make fun of them, they've never dealt with this before. Their infrastructure isn't made for snow and freezing."

This one is for you.

Where I live 108°F with 80% humidity with no wind is normal.

Pacific North West is dealing historic best waves 35-40°C or 95-105°F.

First of all. Don't make fun of them for bitching about the heat. Just like Texas isn't built for a freeze and our pipes burst, Pacific North West isn't built for heat and a lot of their homes don't have AC.

If you live somewhere with a high humidity like 80+ HUMIDITY IS NOT YOUR FRIEND. The "humidity makes it feel cooler" is a lie once it gets beyond a point.

If you live somewhere with a lower humidity, misters are nice to cool off outside.

Once you get over 90°F (32°C) a fan will not help you. It's just pushing around hot air. (I mean if you can't afford a small AC unit because they're expensive as hell, by all means a fan is better than nothing).

If you have pets, those portable AC units aren't safe. If your pets destroy the outtake thing, it'll leak CO2. Window units are safer.

Window AC units will let mosquitoes or other small bugs in. Sucks, but that's life.

Now is not the time to me modest. If you have to cover for religious reasons, by all means. If you don't, I've seen people wear short shorts and a swim top. It's not trashy if it keeps you from getting heat stroke.

If you do have to cover up for religious reasons, look for elephant pants or something similar. They're made with a breathable material.

Shade is better than no shade, but that shit it just diet sun after some point. Don't think shade will save you from heat stroke.

I know the "drink your water" is a fun meme now, but if you're sweating excessively you need electrolytes. Drink Gatorade, Powerade, or Pedialite PLEASE. I don't care if you're fucking sitting in one spot all day. That shit WILL save you from heat stroke.

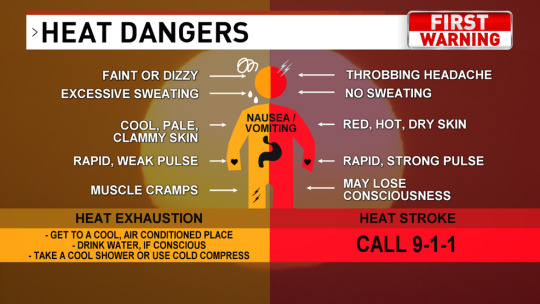

Most importantly. RESEARCH THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HEAT STROKE AND HEAT EXHAUSTION PLEASE!

If you're diabetic and can't drink Gatorade, mix water, fruit juice, and either lite salt or pink salt

If you can afford it, cover windows with thick curtains to insulate the house

If you have tile floors, lay on them with skin to tile contact. If you don't, laying your head on cool counters works too.

If the temperature where you're at is hotter than your body temperature, don't wear heat wicking clothing. Moisture wicking is safe though.

Check your medication labels. Many make you more susceptible to sun and heat

-Room temperature water will get into your body faster. This is something I learned doing marching band in high summer in Georgia, and it saved all of our asses. Sip it, don't gulp it, especially if you're getting into the red; same goes for whatever fluid you're drinking. And just in general drink during the day.

-If you are moving from an air conditioned space to an un-air conditioned space, if at all possible try to make the shift gradual. When my dad and I were working outside and in un-ac houses a few years ago, he'd turn the air down to low in the truck about ten-fifteen minutes before we got where we were going. This way your body doesn't go from low low temps to high temps. S'bad for you.

-If you can, keep your lights off during the day. Light bulbs may not generate a lot of heat, but the difference is noticeable when it gets hot enough. I literally only turn my bedroom light on in the evening when it gets too dark.

Don't be afraid to just like... pour water on yourself if you need to. The evaporation will cool you off.

Put your hand to the cement for 15 seconds. If you can't handle the heat, it'll burn your dog's paws. Don't let them walk on it.

Dogs with flat faces are more prone to heat stroke. Don't leave them out unsupervised.

Frozen fruit is delicious in water.

Wet/Cold hat/handkerchief on your head/neck will help you stay cool.

Pickle juice is great for electrolytes! You can even make pickle juice Popsicles!

Heat exhaustion is more, "drink water and get you cooled off." Heat stroke is more "Oh my god call 911."

Image Description provided by @loveize

[Image description: an infographic showing the difference between heat exhaustion and heat stroke. The graphic is labeled "Heat Dangers: First Warning." Signs of heat exhaustion: faint or dizzy, excessive sweating, cool, pale, clammy skin, rapid, weak pulse, muscle cramps. If you think you or someone else may be experiencing heat exhaustion, get to a cool, air-conditioned place, drink water if conscious, and take a cool shower or use cold compress. Signs of heat stroke: throbbing headache, no sweating, red, hot, dry skin, rapid, strong pulse, may lose consciousness. If you think you or someone else may be experiencing heat stroke, call 911. End description]

Be safe.

-fae

148K notes

·

View notes

Text

hmm, i think i have something useful around here

let me just consult my EDGEWORTH SCRAPBOOK

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

A pair of very round birbs 🐣🐣

Prints + Stickers

22K notes

·

View notes