Discussions of Gender, Sexuality and the Feminine in Magical Girl Media _______ shazleen /// '95 | any pronouns | bi | muslim| british-bangladeshi

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Reminder : search up textural poachers to add to bibliography

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sailor Moon and Motherhood: Part 2

Black Lady & the Matriarch's Shadow

The previous part of this essay duology examined the presentation of motherhood in Sailor Moon through it’s maternal figures. While Usagi’s own mothers aren’t centre stage, Usagi herself becomes the magical mum. In this second part, we’ll be examining the role of the daughter as presented through Chibiusa and her alter ego, Black Lady.

The most important thing to know about Chibiusa is that she doesn’t want to f*ck her dad; she wants to be her mum.

CW: We'll be discussing the weird presentation of Black Lady / Mamoru's relationship / the electra complex of it all and vaguely discussing the trope in anime where daughters want to "marry their father". It's icky and a bit uncomfortable and while this essay is about looking at the psychology behind that specifically for Chibiusa, give it a miss if that's just something you don't wanna read about.

We spoke a little about how Usagi’s celestial past-life mother hardly casts a shadow in the overall story; but Chibiusa finds herself under the shadow of our titular character, a woman who grows up to be a real life goddess in Chibiusa’s timeline.

Sailor Moon in the future is a literal all powerful matriarch, a universe saving goddess acting as the sole ruler of the earth overlooking an eternal city of diamonds; and Chibiusa, is destined to succeed her.

Chibiusa is like, 8.

And she never speaks to her mum. In the previous essay, we discussed a little how Mamoru and Chibiusa easily fall into a parent-child relationship, while Chibiusa is initially very antagonistic towards Usagi. It’s made clear through the story that for whatever reason, Sailor Moon in the future has a somewhat strained relationship with her child; undoubtedly because she’s often off saving the world. Thus, resident house husband Mamoru develops a stronger parental bond with Chibiusa as he’s left at home to look after baby. It’s completely understandable therefore that Chibiusa cherishes and idealises Mamoru; he’s the only parent who’s really emotionally available to her.

Interjection: In before we get further with Mamoru and Chibiusa’s relationship as it’s presented in arc 2, I wanted to also touch on a specific Japanese trope that appears in various works of fiction; namely the weird thing where dad’s joke about their daughters saying they want to marry them ( their dad) when the daughter is young.

This trope is super uncomfortable to me for a number of reasons, but there is something to be said about how its common occurrence in Japanese media can denote the innocence of a child that hasn't developed a lot of complex relationships outside of the home and them trying to model their identity after their parents (with the daughter putting themselves in the role of their mother to understand gender expectations without regard for further implications) and I think this concept ultimately is what my point is with Chibiusa’s whole Black Lady storyline.

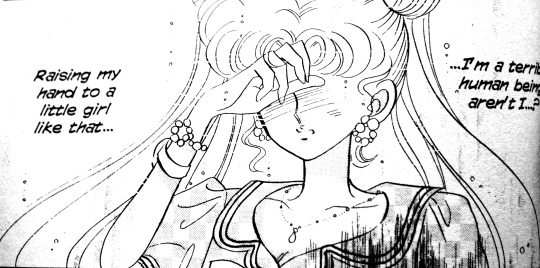

Anyway, so towards the end of Sailor Moon Arc 2, Chibiusa has the whole Black Lady storyline where she becomes a femme fatale (cool) then kidnaps Mamoru and tries to make him fall in love with her or something??? (Not cool) (Gross actually)

But I am a strong believer that there is more to be read from this. Chibiusa doesn’t want to marry her dad; she wants to be her mum. Throughout this story arc Chibiusa’s inferiority complex towards Usagi and her mother are explored. While Usagi is annoyed at Chibiusa getting in between and Mamoru, Chibiusa herself is simultaneously jealous that Usagi has a unique bond with her only emotionally available parental figure (Mamoru) while also yearning for the acknowledgement and love from her mother, which she is currently not getting; her future mum is absent, Usagi is antagonistic. Chibiusa is also unable to fight much at all in the first story arc she appears in, only gaining her Sailor form right at the end (after her Black Lady form is defeated); thus her lack of autonomy and ability to fight further adds to her sense of inferiority. Lastly, and most importantly, EVERY aspect of Chibiusa's character is constructed as a diminutive of her mother's- from her various names and titles to her appearance, she is literally a "mini" Usagi meant to take up the role, but she's also stunted, not having physically aged past 8 despite being hundreds of years old. The weight of her burden of imminent responsibility conflicts with her current status of being a child, lacking in agency. Thus, Chibiusa’s simultaneous idolisation and jealousy of her mother culminates in her taking the form of Black Lady; a warped image of adult femininity that seemingly allows her to gain control of her situation.

However it is not until she repairs her relationship with her mother that she is able to grasp true autonomy via gaining powers as a Sailor Senshi. Her transformation into Sailor Mini Moon is her first step in following her mothers footsteps, but also in actualising her own identity as the next step in the matriarchal legacy. From here on, Chibiusa becomes a strong character in her own right; she is a consistent aid and supporting character to Usagi after the strong bond they form in this story arc; she develops her own friendships, first with Hotaru and later with the Sailor Quartet; she even has her own story arc, which explores her moving away from the role of a child and experiencing her own adolescent independence through a growing romantic interest ( we will touch on this later, I have opinions about Helios ). While Chibiusa begins bratty and impulsive, we watch her grow into a clever and mature girl even more courageous than her mother.

And that’s why Chibiusa is the best, and most important character in Sailor Moon.

#sailor moon#chibiusa#black lady#cw: discussion of chibiusa and mamoru's relationship at the end of sailor moon arc 2#i don't know how to cw for that better suggestions are open and appreciated? its icky but i wanted to talk about it

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Eulogy to Black Rock Shooter

AKA My Wild and Unsubstantiated Black Rock Shooter Conspiracy Theory

A long time ago, I saw a friend posting about a thing called “black rock shooter” on their deviantart journal and I asked them what it was. It must have been circa 2009/10, since it was about the OVA that was soon to release. I’d gotten into Vocaloid pretty bad around that time, right at the fandoms infancy, and I was immediately intrigued by BRS’s creation. I could and would talk more about it ; it’s an interesting case of various creatives building off each other to make a collaborative media property, and one of the earliest instances of this coming from the vocaloid community.

But that’s not why we’re here; we’re here for my hit piece on Black Rock Shooter 2012.

But let’s roll back a bit, to the OVA first. Now, for the purposes of this blog, I’m only going to be touching on the OVA and 2012 anime. I know there’s a few games, manga and a new anime that came out this year, but I’m interested in BRS mostly as a magical girl property, so I’m ignoring media that doesn’t involve the duality of a normal girl / magical girl in the plot. Speaking of, BRS’s OVA is a simple story; Mato and Yomi are two girls who meet each other as they join a new school and immediately hit it off. However Mato is more outgoing, and soon Yomi finds herself sidelined in Mato’s flourishing school life. In another world, a seemingly twisted version of Yomi is gaining power as Dead Master, and it’s up to Mato’s other self, Black Rock Shooter to defeat and subsequently rescue Yomi from her own darker emotions.

There’s something incredibly relatable to me about the short narrative presented to us in this OVA. The quick way Mato and Yomi befriend each other and reach that level of intimacy within their friendship reflects my own experience as a young teenaged afab; often your most intense relationships at that age are with friends you made, in retrospect, for the convenience. Not that Mato and Yomi don’t have a genuine connection; but more that it’s clear during the OVA that they have differing interests and levels of openness, leading to their friendship straining over the course of the story. There’s also a distinctive saphic edge to their relationship too; the disappointment and abandonment Yomi feels, which instigates her downward spiral, also mirrors the feelings of many young queer women, who find themselves in incredibly emotional and weighty relationships with their best friends, who often don’t have the language to explain why they want to spend so much time with them, why they feel such jelousy when that friend is away, or why that friend in particular is so important. This makes it all the more sweet when the conclusion of the OVA is Mato gaining her powers as BRS in order to save Yomi, proving she also sees Yomi as important. The final scene where BRS breaks out of her chains and defeats Dead Master with not her iconic sword or gun, but with a hug, dispelling Yomi’s anger and sadness, always gets me. Despite the somewhat edgy pckaging, the Black Rock Shooter OVA presents a sweet story about a friendship between two girls, and about girls rescuing and caring for each other.

Cute. Nice.

The Black Rock Shooter Anime throws all that out the window.

The anime starts out close enough to the OVA, though with a notably expanded main cast and some adjustments to the characters relationships. In this version, Mato has a pre-existing friendship with Yu, a character who does appear in the OVA but who I glossed over, and Yomi is friends with a new character who I despise. Black Gold Saw is also here.

The first few episodes are normal enough as we follow both the every day storyline and a parallel narrative with BRS, giving us more insight into the connection between the other world and our world. While I have my own petty gripes about the expanded cast taking focus away from Mato/ BRS and Yomi/Deadmaster, I concede giving them other girls to bounce off is a good shout. However the characterisation of all the cast goes right into yandere mode; unlike in the OVA where Yomi’s withdrawel into depression feels gradual and foreboding, the overblown drama of the anime removes any sense of realism from the scenes. What could have been an intimate look at the interpersonal relationships between a group of girls becomes a melodrama interlaced with cgi fight scenes.

The plots between the two worlds feel more disconnected than ever; despite all the new backstory provided, there’s no compelling through line between the real world and other world plots. The worst slap in the face is episode 5, which is a complete inversion of the OVA’s ending; Mato goes into the other world willingly to save Yomi, only to find she’s murdered Dead Master. Expectedly, she flies into a blind rage as a result of this. To add insult to injury, the plot wraps up so neatly after this, to the point where one of the final scenes is all the girls giggling together, it feels completely bizarre. The conclusion is unearned and the core conflict of the girl’s tumultuous attachments to each other, though resolved on paper, feels like it wasn’t ever truly addressed.

I don’t really expect all magical girl media to be uplifting, especially since this particular franchise is definitely not aimed towards the same middle school girls it depicts, but the radical shift from a somewhat eerie but ultimately good natured narrative focused on friendships to outright torture porn felt inexplicable on the first watch. I couldn’t understand how a story that was ultimately so wholesome and clear cut could lose its way so severely, and in such a short time. Afterall, there was only a 2 year gap between the OVA’s release in July 2010 to the anime’s in February 2012, and the OVA was clearly meant as a proof of concept for a longer show. What could have possibly lead to this change in direction?

It was MADOKA.

Puella Magi Madoka Magica came out squarely inbetween BRS’s OVA and Anime in January 2011. I don’t think anyone foresaw how wildly popular the show would be; and anyone who was there at the time knows that one of the key components that made Madoka the success it is was the shocking nature of the plot and how it juxtaposes the cute aesthetic of magical girl media with the tragedy and violence experienced by the main characters.

This is where my speculation comes in.

The facts as I see them are as follows;

Black Rock Shooter OVA comes out with modest popularity backed by the vocaloid communities that supported the project in it’s early days

BRS is never intended as a widely syndicated show, and is very independent in it’s release. It isn’t intended for a mainstream shoujo demographic.

Madoka comes out; it’s a seinen pairing cutesy magical girl designs with surreal aesthetics and focuses on the psychological turmoil of its young female cast and a massive hit

BRS anime comes out a year later with a bigger focus on its character’s suffering and an overall edgier vibe

My conjecture is I don’t think it’s out of the realm of possibility that the production on BRS’s anime saw how well Madoka did and wanted a slice of the pie. It is only after Madoka’s airing that we see this hard shift. BRS 2012 was trying to capitalise on the zeitgeist’s interest in watching girls suffer, and it sucks for it. The voyeuristic framing of the girl’s mental breakdowns, the focus on body horror and maiming and the way we hardly see any real positive real world interactions with the girls towards the latter half of the story ( until the weird ending ) feels like proof enough to this theory. There is a preoccupation with creating a marketable property to serve male fans emanating from the series; there is no care given to try and depict the real friendships of girls. Instead, the relationships are needlessly twisted and again, come to no meaningful conclusion aside from murder. While I have my reservations about Madoka, even it had the decency to ground our characters more extreme behaviours in understandable motivations. Black Rock Shooter 2012 is a sloppy repackage and disappointment on almost all fronts-

At least the opening still slaps.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sailor Moon and Motherhood: Part 1

Why Chibiusa is essential to Sailor Moon and I will Fight You on this

When I was a kid, I never really paid much attention to Chibiusa. I had vague memories of her during my childhood experience of the show as either Usagi’s sister and or weird child, and when I started to get more into the fandom in my tweenaged years, I was again, pretty uninterested in her. I remember later, at a convention when an older table mate asked me if I liked Sailor Moon post season 1; I was confused, because yeah, I liked all of Sailor Moon. That’s when they explained to me that Chibiusa’s addition in the second season was a major upset in the old fandom of the show- people hated her and how she disrupted the status quo.

But I posit that Chibiusa is in fact the best and most important character in Sailor Moon, and in this essay I am going to tell you why.

Chibiusa is essential to the narrative of Sailor Moon for one key element she introduces that propels Usagi’s character development further than any villain; the struggle of motherhood.

I am going to make my disclaimer now in before anyone says anything: Yes, it is cliche, stereotypical ect ect that Sailor Moon is relagated into a mum. Yes, it’s very conservative and traditional for our female heroine’s character development to hinge on motherhood.

However what’s not typical is how much Usagi hates and struggles with parenthood, and how this becomes a major driving force of her character.

Usagi’s relationship to Motherhood

Usagi herself has the blessing of two mothers present in her own life. However, neither make a huge impact in the ongoing narrative; her earth mother, Ikuko, falls squarely into the role of comedy relief parent in both the anime and manga, and her celestial moon mother Queen Serenity serves as mostly a conduit for backstory exposition before slipping out of the plot for good in the first story arc.

This very much mirrors the majority of Magical Girl series; for a women centric genre, maternal role models aren’t really around much. The only mum of a main character I can really think of who really reflects an image of modern motherhood is Madoka’s Mother in Puella Magi Madoka Magica. I’m writing another essay about Motherhood and Mature Feminity in the Magical Genre; it’ll be linked when it’s done.

However, the GOAL of motherhood and domestic femininity is ever present; some examples are in Shugo Chara, where one of Amu’s dreams is to be good at cooking or in Tokyo mew Mew where Ichigo dreams of being a bride. These, and other examples glorify the traditional value of getting married young and beginning a family.

Sailor Moon on the other hand actually explores what it means to achieve that goal; albeit through some metaphor.

Because when Chibiusa falls out of the sky at the start of arc 2, Usagi essentially becomes a teen mum.

Suddenly, she isn’t just a young woman in love with her destined reincarnation boyfriend; she’s now saddled with the responsibility of a child from the future, and now both she and Mamoru have to prioritise this child above all else, including each other.

Mamoru, being the perfect anime boyfriend, of course takes to this easily, but Usagi loses it. She’s just spent all this time being the centre of Mamoru’s world, and fighting to save their love, but now there’s a screaming kid in her way. And she hates Chibiusa, and Chibiusa is hardly amicable to her. Unlike with Mamoru, who easily falls into a carer dynamic, Usagi and Chibiusa initially start off acting more like sisters; I often think about how this reflects some real life dynamics I’ve seen between mothers and daughters who are closer in age, where the mother had kids very young. The conflict between the two of them culminates towards the end of the arc when Usagi slaps Chibiusa, and in that moment realises that she, Usagi, is the bad guy here.

Because Chibiusa is a child; HER child.

This sets off Usagi’s biggest change as a character; she begins to learn to be truly selfless, for her daughter. While the other characters in Sailor Moon up until this point have helped to develop Usagi’s character in their own way, it isn’t until this moment she really begins to change. Her friends show Usagi’s compassionate side; her ability to connect with others and her gentle nature that attracts others to her. Usagi’s relationship with Mamoru shows her tenacity and the lengths she’ll go to for others that are important to her. But these relationships don’t push her the same way as Chibiusa does; with her friends, she is still the princess to be protected; with Mamoru, he’s the indulgent lover, and she’s allowed to stagnate in their romance. It is Chibiusa who spurs Usagi to grow; Chibiusa can only be a dependant to Usagi. This is the first time Usagi must truly choose to protect someone.

And through it, Usagi grows up from a bratty girl into a young woman who’d do anything to protect her daughter; it is the love and genuine friendship she develops with her own daughter that makes Usagi into the loving, brave and heroic Sailor Moon.

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are some good examples of popular magical boy anime?

Side question which ones are good in your opinion?

Hey there!

This is such a fun question, and it also unlocked some deeply buried memories in me, so I'm going to give a really long answer to this one!

I should also say that several Magical Girl series do have prominent magical boys in them who either serve as deuteragonists or are part of the supporting cast. Some good examples of prominent ones would be Syaoran in Card Captor Sakura, Ikuto and Tadase in Shugo Chara, and Chat Noir in Miraculous! They are all pretty plot relevant and have their own little character arcs if I remember correctly; Tuxedo Mask/ Mamoru in Sailor Moon is also here too.

So when I was writing this last article, I was mostly thinking of the kind of Magical Boy series that have come out in the last decade.

The main one that I had in mind was the infamous Cute High Earth Defense Club. I watched an episode or two way back when it was airing with some friends and the general vibe back then was this series was a joke.

I also was thinking of Is this a Zombie, a series which might be good but I have not yet tried because uh it looks like moe trash and I don't wanna!!! (I'm not a fan, I'm sure someone out there likes this kind of thing! I'm judging by appearances, and the premise seems a lil creepy so it's never been high on my priority list of things to check out. It's just not for me I think!!)

There's also the Tokyo Mew Mew spin off, Tokyo Mew Mew Ole ? I have a lot of Thoughts (tm) about this one, and I'm planning a short essay about audience point of view characters and the influence of otome games on this particular property. I actually didn't realise until now it's just...kept going, and I'm gonna have to read it all I guess?? (So many thoughts lol)

Those are pretty much the main manga / anime examples I had in mind. I would also count Steven Universe as a Magical Boy show, though it's of course western. I also think the ongoing webcomic series, Magical Boy, is meant to be pretty good? It brings together a lot of stuff about gender / queer identity and magical boy stuff, so that's cool and worth a read for sure!

Lastly, there is one that I had pretty much forgotten about and then this ask unlocked the secret memory of an anime/manga series that had us in its grip back in '08.

So DNAngel exists. (For those not in the know, the two people above are the same guy lol )

It has like two separate Magical Boys, they have wings, they are enemies. There's past life bullshit, crimes, and school life. There's also a love square if I remember correctly? I never managed to catch that many episodes of this show, and the manga was on and off Hiatus for years until it just completely stopped in 2011, so I never really bothered to finish reading it since I thought it would just STAY unfinished for all time.

BUT THEN THE AUTHOR CAME BACK AND FINISHED IT? IT ENDED LITERALLY LAST YEAR?? So thanks asker for reawakening me to this distant memory haha! I think I'm gonna add this series to ones I want to read and write about, since it's kind of unique!

Oh also, I think I should say that Yu Gi Oh might genuinely count too, since Yugi has a straight up transformation sequence but...I'm not gonna talk about Yu Gi Oh here haha. I feel if I start veering too much into Shounen, the scope of this blog might spiral out of control.

Edit: I SHOULD ALSO SAY; if you’re looking for anime and manga, my picks would be DNAngel and Tokyo Mew Mew Ole. DNAngel is much more focused on the dynamic between the main character and his rival, relationships to his love interests and the backstory. Tokyo Mew Mew Ole is more cute, with a fun team dynamic !

Thanks for the Ask!

#ask#sailor moon#cardcaptor sakura#tokyo mew mew#miraculous ladybug#shugo chara#magical boy#magical boy webcomic#is this a zombie#cute high earth defense club love#steven universe#dnangel#tokyo mew mew ole

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genesis of Genre: Part 4

Post modern Puella Magi and what the future holds for Magical Girl as a genre

Author’s note:

I wrote the bulk of this essay the same time as the previous essays I’d posted to this blog. There’s an interjection partway through that notes where I begin to rewrite parts, and you can check the addendum at the very bottom of the page if you want to read about my meek return.

The “Golden Age” of Japanese Magical Girl media would be the 90’s and early 2000’s, introducing us to to genre defining series like Sailor Moon and Card Captor Sakura, alongside the more Avant-Garde series like Utena. As mentioned previously, Sailor Moon ushered in an array of series clearly influenced by it’s sentai style dynamic, but those kinds of stories are much more rare these days. I believe we are instead in a Post-Modern age of Magical Girl Media. It’s more common to see a deconstruction or subversion of the archetypical Magical Girl narrative as opposed to seeing it played straight. While some pick up on the darker elements of the genre, others choose to subvert expectations; we’ve had everything from stripper angel magical girls to anime centred around groups of magical boys in the last decade. However, not all series are made equally, and in this (perhaps overly long) segment we’re going to look over the Magical Girl genre hits of the mid 2000s to the 2010s.

Utena began the dialogue with darker themes; Akiyuki Shinbo’s 2004 Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha continued it. Nanoha is notable in being one of the first contemporary Magical Girl shows that was not aimed at young girls; instead it was a seinen, aimed at young men. We’d previously had lots of instances of men writing series, along with an uninvited male gaze, but these series were still targeting an audience of young girls. Nanoha is also different than pre-Sailor Moon examples like Cutie Honey, which is a Shounen, as instead of being more of an action comedy, it delved into darker themes of abuse, on top of being a spin off of an erotica visual novel game; all of which is made much more disturbing when we remember the characters are all elementary school aged children.

Real talk for a moment: it sucks a genre that started out being about young women’s friendships and dreams for the future eventually got turned into torture porn for crusty men. And it didn’t stop with Nanoha.

Shinbo returned in 2010 with the acclaimed Puella Magi Madoka Magica, the huge franchise that now comprises the original anime, several films and countless spin-off manga. I’ll save my complex feelings towards Madoka for another time; the key point is that for better or worse, it is a definitive deconstruction of all Magical Girl media that comes before it. Madoka succeeds in examining the human experience of suddenly being thrust into a world of aliens and magic better than it’s predecessors. The character’s youth and immature decision making is central to the story, and the tragedy stems from the magical girls being children who act rashly and aren’t able to fully process the consequences of their choices until it’s too late. While there is a portion of the audience that is undoubtedly there to view misery being inflicted to young girls for whatever gross whims, it can’t be argued that Madoka’s narrative managed to be compelling to people of all ages and genders, and that is a strength of it’s story. However at the same time, it also lead to a lot of copycats, just like Sailor Moon before it, because there is unfortunately a market for teenage girl torture porn. Please look forward to my Black Rock Shooter hit piece.

On the possibly brighter side, we also had more comedic subversions. First, there’s the very specific brand of Magical Girl shows that Studio Gainax and Trigger started putting out in the 2010s; both Panty and Stocking with Garterbelt and Kill La Kill take the sexualisation of the female body present in old school works like Cutie Honey to the logical extremes, and despite being so overtly sexual and fan-servicey, both wind up completely absurd by the end of it. These are obvious subversions of the idea of Magical Girls as pure and innocent; Panty and Stocking is particularly interesting because of how it blends Japanese and American art styles – particularly cartoons like The PowerPuff Girls- to create a cute and cartoony presentation that contrasts with the crass humour and antics of its titular characters. Conversely, I remember watching Kill La Kill during it’s original run and being stunned that by the end of it, when the finale happens and all the characters are completely naked, I was astounded to find I’d become completely desensitised to the naked human form (all this before 3 years of life drawing).

-a future interjection- I’m writing this at the time of posting. The part of the essay you just read is a part I’ve mulled over for over a year. My original essay from 2017, which I’m using as a basis for this much larger work, spoke quite favourably of both Kill La Kill and Panty & Stocking. I think I simply could not leave it as is.

I recently rewatched parts of both Panty and Stocking and Kill La Kill. Surprisingly, Panty and Stocking held up well, so this isn’t about them. Kill La Kill on the other hand simultaneously held up better and much, much worse than my first watch during it’s original run. (I think I might begin doing straight up reviews for shows soon; but that’s for another post)

My main thought upon rewatch was my attitude now, and my attitude nearly 10 years ago is a real reflection of the ways popular feminism, and my own ideologies have shifted over time. Originally, I’d felt the display of the main character’s bodies, that they were powerful and strong while wearing the skimpiest chainmail bikinis, was almost a power move. I especially admired Satsuki’s character, being someone so unflinchingly determined, and feeling no shame in her body as she served a higher conviction.

I just don’t think I can look at the show in the same way now. Yes, the show is still absurd; I do still think it veers into the surreal. But its far more uncomfortable than I remember.

Either way, both these shows still serve as a perfect subversions of the classic magical girl story. -end-

Sliding across the spectrum, there’s also the notable increase in shows that star Magical Boys. On paper this might seem like a thoughtful take on how we present young men but in reality most of these series are played for comedy and or fanservice for a female demographic. Though I’m sure there’s merits to it, it’s a far cry from earlier Magical Girl series which deeply examined themes of gender and sexuality. At best, these are missed opportunities!

We’ve also seen an uptick in remakes and sequels to more nostalgic franchise; Sailor Moon Crystal is the notable example, as is Card Captor Sakura’s Clear Card Arc which is currently ongoing. Tokyo Mew Mew, at the time of writing, has now seen two separate revivals with the short lived magical boy spin off (???) and now with a new anime version airing as I write this! I think the revisiting of these older properties is both a symptom of our expected nostalgic media cycles (see, the 30/20 year cycle), but also a reflection of the current want to revisit late 90’s and Y2K media again, and companies as always being more willing to bank on pre-existing franchise.

The last few decades of Magical girl media has, to be honest, been a mixed bag. However there is one, single shining light for me, and that is 2013’s Little Witch Academia, and it’s subsequent sequel film and anime series. Somehow, the creators of Kill La Kill, the most edgy, ludicrously sexual and action orientated Magical Girl show in recent years also created the most sweet and wholesome. Little Witch Academia takes the genre right back to its roots, utilising the Magical Witch Archetype with a main character named Akko, just like the heroine of years passed, and centres the relationships between the students and teachers at their magical academy. The series also stands out from Trigger’s other works as it didn’t start out as a syndicated show; the original OVA was Trigger’s first outing, created as a project for new animators, and its sequel film was crowdfunded to increase it’s original runtime of 20 minutes to a full 50. The eventual series was created in collaboration with Netflix, and I believe this alternate production also lends to why Little Witch Academia successfully unshackles itself from the troubling tropes that have stagnated Magical Girl media in recent years. Little Witch Academia is the genre returned to it’s primordial state; devoid of fan service and rich in substance, it’s a love letter to the genre.

Addendum:

I started writing this blog around the winter of 2020/Jan 2021. A lot of terrible things have happened in my personal life since then but recently, I started feeling like I could write some essays again, for fun. This particular essay had been sitting in my storage since back then too. As I said in the post, part of what made me not publish it until now is because I'd started to re-contextualise some of the writing with my current views, and it felt incomplete to post it as I'd written it; as in, quite true to my perspectives in my original 2017 essay. I still have a lot I want to write, both based on my original work and also large pieces, but I think I might start writing the essays out of order+mix in some more general reviews with my personal thoughts added in. I do intent to write a more contextual essay about western magical girl shows, but I'll leave that for later maybe! Thank you everyone who followed this blog and read my work so far. I hope I can start posting more frequently!

#Revolutionary girl utena#sailor moon#puella magi madoka magica#magical girl lyrical nanoha#magical girl essay#context#cutie honey#tokyo mew mew#little witch academia#kill la kill#panty and stocking#black rock shooter

77 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Sorry to bother you, I was just wondering if you plan on posting other essays about magical girls on this blog, I really liked the series and was hoping you would post all of it. If you dropped it for whatever reasons, it's not my intention to pressure you to continue it, just know I absolutely love your writing!

Hope to hear from you again!

Hi there!

I definitely plan on posting more and it means a lot to me that you're interested in my writing! This blog is a little self-care hobby for me, so I've not had a lot of time to write since christmas, but I'm hoping I'll have a bit more time soon!

Thank you for this kind message anon! It's really motivated me and warmed my tiny heart <3

1 note

·

View note

Text

Genesis of a Genre: Part 3

Utena’s dual identity a Sapphic icon and Harbinger of Queer Tragedy

Prior to creating Revolutionary Girl Utena, Ikuhara had previously directed Sailor Moon’s anime, which shows from the similar art direction and character designs, though Utena is perhaps more classical than Sailor Moon, going back to focus on a singular protagonist rather than a team. Like Sailor Moon, Utena was also exported to the west and became a classic to western audience, and it’s still referenced in mainstream media today. However, Utena’s overtly darker themes were a welcome change of pace for viewers who perhaps tired of it’s predecessor’s overall lighter tone and penchant for wrapping even life-threatening storylines up with a happily ever after.

Taking a quote from Napier’s 2005 essay:

“Utena is deeply concerned with a form of apocalypse…more appropriately a baroque apocalypse, of adolescent emotion where everything is larger than life, identity is at it’s most problematic, and life is lived in extremes.”

I really love Utena conceptually; where Sailor Moon brought queerness to the table, queerness is the point of Utena. Where gender roles are explored in Sailor Moon, the weight of gendered expectations is a key conflict in Utena. Like Princess Knight before it, Utena speaks about the balance of the masculine and feminine within one’s own identity through the imagery of european fairytales, princes and princesses; the eponymous Utena is a young girl who is rescued by a prince as a child; and then resolves to be a prince as an adult. However she herself is not inherently magical; she does not need to transform to explore her gender, as it’s something that’s a part of her identity well before she engages with anything magical.

It is Anthy instead who is the Magical Girl in Utena; Anthy who is classically demure and feminine; Anthy, a submissive, exotic prize to be won; Anthy from who’s chest Utena must draw a blade from to unlock the power of revolution every she battles a foe, all in order to protect Anthy from other suitors. However, unlike Utena, Anthy isn’t innocent; instead she’s acutely aware of her place in this world and unlike Utena who naively fights against the powers that be, Anthy is resigned to them. As such the anime deals with the complex relationship between gender, sexuality and power as the plot unravels and the relationship between the two main girls develops.

Yet while I love Utena’s mature themes, I feel to an extent it’s also the beginning of a trend in darker Magical Girl shows and a shift in audience demographics. While both Utena and Sailor Moon are definitely shoujos marketed towards girls, Sailor Moon’s anime adaption does sexualise its young female characters much more than the manga, most notoriously with its transformation sequence (I have a whole essay planned for the transformation sequences and a whole separate one for narrative changes to Sailor Moon in the anime). Utena, with it’s more adult themes expectedly also engaged a more adult audience. Both shows also had a peripheral demographic in straight boys and men, which the animation studios courted with the higher contents of sexualised imagery in both shows.

It is not a coincidence in my mind then, when a few years later Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha would come out and completely separate itself from female audiences, being a magical girl show squarely aimed at men. The director of the show, Akiyuki Shinbo, was at the time known for the Triangle Heart erotic video game series, and is now known for creating Puella Magi Madoka Magica.

Yeah, you see where I’m going with this right?

While shows like Cutie Honey (the show that literally invented the transformation sequence) definitely also catered to the male gaze, the combo between this and Utena’s grim themes resulted in the birth of series like Nanoha, where stories about young women, growing up and facing threat are no longer about providing a space for young girls to see the heightened emotions they may experience, but instead about gratifying straight male sexual fantasies. Narratives about girls exploring queerness were now there to provide titillation for the heterosexual male viewer. It is not Utena’s fault, but a sad ode to the evolution of the genre as a whole, one that echoes still today as more and more magical girl media comes out to cater to and thrive off the wallets of older male audiences while stories about the aspirations of young women are ignored.

#magical girl essay#magical girl lyrical nanoha#cutie honey#sailor moon#context#puella magi madoka magica#revolutionary girl utena

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genesis of a Genre: Part 2

Sailor Moon is the most important Magical Girl franchise and Yes, this is the hill I’ll die on.

I don’t think it’d come as a surprise to anyone who knows me personally to know that Sailor Moon is my favourite Magical Girl series. It’s not just because of nostalgia or an admiration of the story though; it’s also because I think Sailor Moon is the most influential Magical Girl series, and I would fight you on that.

Sailor Moon set the standard for what we would see as the contemporary Magical Girl; combining the tropes from preceding Magical Girl shows with Sentai Shows, Sailor Moon began the idea of a team of Magical Girls fighting against a shared cause. While Usagi is definitely the main character of the manga, she’s supported by a colourful cast of compatriots, who are each fleshed out even more in subsequent adaptions and additional material (think the rpg game & Sailor V manga). Growing up, and even when I speak to fans of the show now, everyone had a different character that was their favourite- even when I showed the show to friend who weren’t huge fans of anime, they all had a character they naturally gravitated towards. The broader cast also brings the relationships between the girls to the forefront, ranging from friendships, familial and even romantic. Miss Naoko really did bless us with a Lesbian Polycule all the way in the 90’s; and this isn’t conjecture, there are canonical lesbians and queer people in Sailor Moon.

Also, on top of all of this it’s fucking great??

Girls fight intergalactic threats with love and friendship, fuck yeah??

Sailor Moon truly broke ground in so many ways because of all this, and it gained massive popularity both in it’s home country and internationally. It’s still regarded as one of the best Magical Girl Franchise, and it’s influence can be seen both in Japanese and International Magical girl Media. Series like Tokyo Mew Mew, Mermaid Melody and Shugo Chara all carry influence from Sailor Moon following a trend of a team of Magical Girls (or in the latters case, Magical people). As mentioned in the previous article, Toei went on to create two separate franchise with the team dynamic at it’s core; Ojamo Doremi and it’s cashcow franchise, Pretty Cure. However while all of these borrow many of the aesthetics of Sailor Moon, none of them quite tackle the same themes as the original. I’m going to get into talking about Femininity and Motherhood in Sailor Moon at a later date, but for comparison sake let’s just say that none of the aforementioned series ever touch upon these issues with any depth. We get some variety in the kinds of “feminine” we are presented with via the ensemble casts, but there is little if any discussion of the roles of women or queer femininity. At the very most, there’s some hints in Tokyo Mew Mew that Mint is infatuated with her female teammate Zakuro, though nothing ever comes of it. In Shugo Chara, a character who is initially presented as a girl is shown to be born as a boy and resents having being made to dress as a girl by their family. It’s also difficult to view this character as a trans person since they identify with the gender they’re assigned, and only present as anything alternative due to external forces rather than as a personal exploration of self. Furthermore, in none of these cases is it a main character who experiences queerness; unlike in Sailor Moon , where Usagi has canonical romantic entanglements with not one, but two queer people, and Haruka is allowed to be powerful, have romantic relationships with same gender partners and experience a gender fluid identity with no repercussions or pressure from external forces.

As for Sailor Moon ’s influence overseas, there’s no doubt that it’s the single show that defined Magical Girl as a genre for so many in the west (including myself). To this day, Sailor Moon continues to be referenced in western mainstream media (mainly through the anime’s iconic transformation sequence), and its notable that western Magical shows will nearly always follow the team based dynamic the Sailor Moon defined. Think how W.i.t.c.h, Loli Rock and Winx Club all feature the ensemble casts, with Winx Club even carrying over elements of the the Magical Princess Archetype too. Star vs the Forces of Evil also takes from the Princess Archetype and while it stars only a single Magical Girl as a lead, it borrows plenty aesthetically. Miraculous Lady Bug comparatively is more influenced by the the current interest in Superhero media, but the dynamic between it’s main couple, Marinette and Adrien, is very reminiscent of early Sailor Moon’s dynamic with Tuxedo Mask while she still isn’t sure of he’s friend or foe, while they constantly cross paths both in and out of costume. Even Steven Universe has several overlaps with Sailor Moon ; the beautiful pastel art direction of it’s background paintings, the focus on living up to a mother’s legacy and even a charming polycule of queer space femmes raising a child together.

Listen it’s 2021, we’re still in a pandemic and we’re way past cringe, so I’ll come out and say it: Sailor Moon walked so Steven Universe could run. Whether you accept it or not, Sailor Moon set a standard for Magical Girl series around the world, and we’re only now seeing those ideas about gender and queerness come to full fruition.

#sailor moon#steven universe#magical girl essay#magical girl#queer theory#feminist theory#tokyo mew mew#mermaid melody#shugo chara#w.i.t.c.h.#winx club#lolirock#miraculous ladybug#star vs the forces of evil#context

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genesis of a Genre: Part 1

Defining the four key archetypes of Magical Girl characters found in Japanese Magical Girl media.

I feel this wouldn’t be a great body of research without outlining some kind of historical context for the media were talking about! In this mini-series of essays I’ll be going over the first part of my research, which seeks to define the key influences of the Magical Genre, including industry and production influences, and provide an outline for reoccurring archetypes and conventions found in the narratives. This focuses mainly on Japanese Media, but I might do one about the history of western Magical Girl stuff too!

I pose there are four key archetypes for the protagonist (and sometimes supporting characters) of any Magical Girl franchise: The Witch, The Princess, The Warrior and the Idol. Any given Magical Girl may be one or a combination of several; for example Usagi (Sailor Moon) is a combination of the Warrior and Princess while Akko (Little Witch Academia) is the Witch.

Girl Witches and Growing up

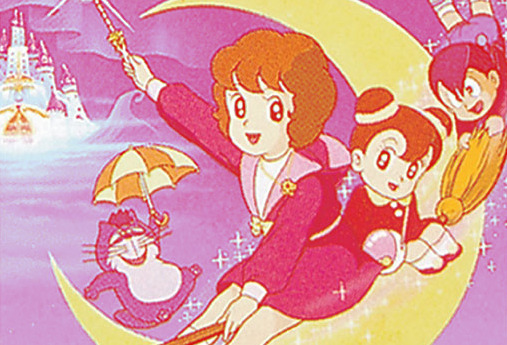

Many writer have cited the Witch as the first true Magical Girl Archetype; Sally the Witch and Magical Akko-chan are often regarded as the progenitors of the Genre. Both were published in the notable shoujo magazine Ribon in the 60’s and both were adapted into anime by Toei; Ribon notably also published several of Arina Tenemura’s works, including the Magical girl series Full Moon while Toei is the studio behind Sailor Moon’s anime in the 90’s, as well as creating both the Ojamo Doremi and Pretty Cure franchises in the late 90’s and 2000’s respectively. Sally was influenced by the popular American sit-com Bewitched, but reimagined to focus on an adolescent girl-witch who must keep her identity secret. She was often alone in her quest too, perhaps with a magical pet confidant, unlike future entries where Magical Girls would be a part of a team or have complex relationships to others with powers. There were ideas of destinies or even secret royal birth-rights, but ultimately the protagonist was simply a girl, who was born with magical powers.

These early entries set off the precedent for Magical Girl as a genre being inherently linked to themes of coming of age; the magic of the young characters often being allegorical for childhood innocence and ultimately being abandoned or given up as a part of their growing up. It’s notable at this point in the genre, very few or no women worked in these spaces; both Sally and Akko are written by men. I wonder how the genre may have been different if it was not the case; could these young girls be allowed to grow up magical if a woman wrote their stories? I feel this is a reoccurring theme in so many future works, so stick a pin in that.

In the contemporary sense, while Magical Witches aren’t quite as frequent as they were in at the start of the genre, there are still several shows that carry on the tradition. Ojamo Doremi, while borrowing several features from later warrior/sentai styled shows like Sailor Moon, has the lead characters as girl witches again. Madoka, though stylistically more a Warrior styled show, also alludes to the history of magical girl as a genre with the naming of it’s initial antagonistic characters being “witches” while the leads are “puella magi” or literally maiden witches, though the way it explores these themes is a conversation for another essay. Lastly, Little Witch Academia is the most recent notable example of the pure Magical Girl Witch. The franchise is like a true homecoming for the genre; I could wax on about how it’s a culmination of everything the genre’s gone through in the last 60 years. From it���s allusions to flashy transformation sequences, to it’s shift in focus to friendships between girls, Little Witch Academia is an absolute treat; it’s main character being named Akko undoubtedly a homage to her ancestor of the same name.

Idol Aspirations

As the genre progressed, women were…allowed into the magazine offices. The genre was reinvigorated in the 70’s, and with these new author came a shift in focus. Stories began to take more elements from Shoujo staples, with more focus given to interpersonal relationships and aspirations of the characters coming into place.

The Magical Idol singer is this weird niche specific thing that sort of came from this period of time, though I think she signifies more than her actual appearances across the genre. Authors for the first time wanted to create stories that reflected the goals of its readers- and at the time that meant Idol culture and aspirations of being a singer or celebrity. While contemporary examples of a by-the-book idol character is a bit rare since values have changed over time, she was the first step in magical powers for Magical Girls no longer being a part of a divine destiny or something to grow out of but instead powers being the means for Girls to achieve their goals. Magical Idol singers also often incorporate the characters noticeably aging up when turning into their alter egos, serving a duel purpose of giving younger viewers a sort of aspirational character to live through while also unfortunately allowing the animators to get away with fan servicey shots of the more mature looking character.

The originator of this subgenre would be Magical Angel Creamy Mami, though Mermaid Melody would be an immediate example I’d personally think of for the Idol type character (with a big old additon of the Princess archetype too), a better example would be the aforementioned Full Moon, in which the sickly Mitsuki transforms into a Magical Idol singer to both live her dreams as a singer and to reunite with her childhood love. I’d also argue that series the Utena and Madoka follow along with this influence; in both cases the characters agree to engage with the magic of their worlds to achieve some kind of goal or dream. Still, I feel there’s lots of potential with this kind of outlook in Magical Girl stuff..!! Perhaps in the future we’ll get more magical girls focused on their careers…

Warrior Princesses

I feel throughout this essay, I’ve been noting how the Warrior and Princess archetype often overlap with the other genres, as well as each other. I believe this is because the ancestor of these two defined archetypes is one and the same, and also the series I believe that actually started magical girl as a genre; that being, Osamu Tezuka’s Princess Knight.

Princess Knight, and bare with me on this, is a story about a Princess born with both a “girl” and a “boy” heart. She forsakes her life as a princess to escape some cruel fate that’s in store for her, and masquerades as a prince by using her “boy” heart. While this is an extremely dated view on gender, it immediately gives us three defining features of magical girl as a genre: First, the Princess archetype, which often holds influence from european fairytales and magical destinies; Second, the Warrior Archetype, in which the lead character must don a more traditionally masculine role of protector against some evil power, and lead a double life; and lastly, the introduction of gender roles as a theme into the genre, and the role of femininity and masculinity in the identities of our characters.

All of these tenets are then repeated in both Sailor Moon and Utena decades later, and it’s arguably these two series that carry it forward to influence future franchises. As the major examples of these archetypes are one and the same, it is difficult to parse the two apart, even though they are quite different.

So I’ll try anyway!

I believe the Magical Warrior is defined as a main character or team of characters who are joined by a destiny to fight against some greater evil, while the Magical Princess is defined as a character who is destined to inherit or reclaim a great power linked to a monarchical structure. Both may have themes linked to western fairytales and fantasy, though often Warrior type characters have a wider breadth of influences while Princesses remain closely linked with ideas of fantasy and fairytale royalty.

While Magical Warrior is definitely the most prolific of the archetypes in modern times, arguably overlapping with nearly every storyline, I think Magical Princesses are fewer. For example, Tokyo Mew Mew is a clear cut Magical Warrior story; they girl’s aren’t born with powers (So not witches), they aren’t doing it for a personal goal (so not Idols) and none of them have some divine destiny (not princesses). However it’s a lot more difficult to find a pure Magical Princess story; in Mermaid Melody, but the story overlaps with both Warrior and Idol archetypes. Princess Tutu might be the best example, as it’s a story of retribution deeply linked with elements from european fantasy.

#magical girl#sailor moon#tokyo mew mew#full moon wo sagashite#revolutionary girl utena#pretty cure#little witch academia#mermaid melody#essay#context#princess tutu#princess knight#ojamo doremi#puella magi madoka magica

239 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sometime back in 2017, I’d handed in my dissertation. Roughly five-thousand and five-hundred words long, perfect-bound and with a glossy, illustrated cover, it was a heavily edited down essay about Sexuality and the Feminine in Magical Girl media focusing on OG Japanese Media; I’d had to cut out the third section that covered western entries entirely in the genre. I was at the time and still am really proud of the work as a whole, but since then I’ve always wanted to explore the full breadth of the research I’d done for the project, much of which had to be left on the cutting room floor.

It’s 2021 now and we’re in month ten or so of a global pandemic and so what better a time to revisit it!

As such this series of essays is an extension of that initial work. I’ll mainly be discussing Magical Girl media in relation to the topics of the feminine, gender and sexuality, from the inception of the genre to contemporary franchises. While much of my research (and interest!) is on Japanese Media, I’ll be extending the range of subjects to Western media and discussions of fandom culture and reader expectations. The essays themselves may cover several series while others will focus on an aspect of a specific series. (Yes, that is me warning you all that I’ll be writing a whole essay on Chibiusa Sailor Moon.)

A few disclaimers! I’m an Illustrator, and while much of my contextual studies focused on intersectional feminist readings of comics and sequential narrative art, I’m not at all a specialist in the field. My knowledge and ability at critical writing is limited at best, so please don’t take this as a end all be all take of whatever books or shows I discuss. In regards to the Japanese media I’ll cover, I must acknowledge that I’ll be viewing it as an outsider looking in, and while I have done some research on feminist movements in Japan, my writing will always be limited by a outsider’s lens. I can’t truly speak for the girls the media was initially aimed at or the culture it’s a part of; I’m only offering my perspective. Lastly, as these are essays on the internet I’m going to be liberal with references; while I’ll link to any new material I may read or watch during the course of this new critical endeavour, I’m not holding myself to citing every claim I make. All the references I used from the first iteration of this work will be listed below this introduction.

Finally, before we begin all this, let’s get one thing clear; what is Magical girl as a genre and which media falls into it?

From the perspective of this essay, the Magical Girl genre has it’s origins as an of-shoot of Shoujo Manga, typically aimed at girls between ages 12-14. The genre inherits the focus on coming of age stories and interpersonal relationships from it’s parent, but combines this with fantasy elements and even action and adventure at times. Since then it has grown in both its genre conventions as well as it’s target audience, and the success of notable works, such as Sailor Moon, in western countries has resulted in it influencing media outside of it’s home country. Consequently, I’m taking a flexible stance on what counts within the story and including works as broad as Tezuka’s Princess Knight to Steven Universe within my right to well…write about.

I feel to go into more detail would be spoilers for later essays! So I’ll end off with my list of references. See you later!

Bibliography

Texts

Berkeley, C. Ed. (1997) Broken Silence: Voices of Japanese Feminism London: University of California Press

Blue Delliquanti (2013) Distinguishing characters through fashion: how Sailor Moon does it right. [Onlune] Accessed from: http://bluedelliquanti.tumblr.com/post/54691592736/distinguishing-characters-through-fashion-how

Duffet, M. (2013) Understanding Fandom: An introduction to the study of Media Fan Culture New York: Bloomsbury

Gravett, P.l (2004) Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics London: Laurence King

Ide, S. (1997) ‘Excerpts from Women’s Language, Men’s Language’ in Berkeley, C. Ed. Broken Silence: Voices of Japanese Feminism London: University of California Press, pp. 48-64

Johnson, L. (2007) Third wave Feminism and Television: Jane puts it in a Box London: I.B. Taurus

Johnson, M. (2010) The Little Princess Syndrome. Natural Life, , pp. 34-36.

Liddle, J. (2000) Rising Suns, Rising Daughters: Gender, Class and Power in Japan London: Zed

Luster, J. (2016) Trigger’s “Little Witch Academia” Makes the Leap to TV Anime Series Crunchyroll [Online] Accessed from: http://www.crunchyroll.com/anime-news/2016/06/24/triggers-little-witch-academia-makes-the-leap-to-tv-anime-series

Martinez, D. P. (1998) The Worlds of Japanese Popular Culture: Gender, Shifting boundaries and global cultures Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Michellejb (2014) Evolution of the Magical Girl The Hyped Geek[Online] Accessed from: http://thehypedgeek.com/evolution-of-the-magical-girl-anime/

Miya, Y. (1997) ‘Excerpts from Sexuality’ in Berkeley, C. Ed. Broken Silence: Voices of Japanese Feminism London: University of California Press, pp. 170-184

Napier, S. (2005) Anime: From Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Napier, S. J. (2008) From Impressionism to Anime: Japan and Fan culture on the mind of the West Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Newson, V. (2004) Young Females as Super Heroes: Superheroines in the Animated Sailor Moon [Online] Accessed from : http://www.femspec.org/samples/sailormoon.html

Ohanesian, L (2012) How Puella Magi Madoka Magica Shatters Anime Stereotypes LA Weekly [Online] Accessed from: http://www.laweekly.com/arts/how-puella-magi-madoka-magica-shatters-anime-stereotypes-2373077

Saito, K (2014) Magic, Shojo and Metamorphosis: Magical Girl Anime and the Challenged of Changing Gender Identities in Japanese Society, The Journal of Asian Studies, 73(1), pp. 143-164.

Searle, S. W. (2016) Fatness, Femininity and the Media we Deserve The Nib [Online] Accessed from: https://thenib.com/fatness-femininity-and-the-media-we-deserve

Shodt, F. L. (1983) Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics New York: Kondansa International

Zhou, C (2016) Magical Girl as a Shojo Genre and the Male Gaze Flowjournal [Online] Accessed from: http://www.flowjournal.org/2016/02/magical-girl-as-a-shojo-genre/

Gallery Exhibits

Revolutionary Girl Utena Tribute Art Show (2016) [Exhibition] qpop shop, California. 30 April- 22 May 2016. Website: http://qpopshop.com/main/?page_id=15 [Accesses: 21/11/2016]

Shoujo Manga: The World of Japanese Girl’ Comics (2016)[Exhibition] House of Illustration, London. Date: 18 March-12 June 2016. Website: http://www.houseofillustration.org.uk/whats-on/current-future-events/shojo-manga-the-world-of-japanese-girls-comics [Accessed: 27/11/2016]

Violent Pink (2016) [Exhibition] Gallery Nucleus, California. Date: 21 May- 6 June 2016. Website: http://www.gallerynucleus.com/gallery/533/exhibition [Accessed: 27/11/2016]

10 notes

·

View notes