I make art and stuff. Dunlending rights activist. Pittsburgh, 30s, they/them, same name on Etsy

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

when someone notices your copy of 'gay t-rex law firm: executive boner'

699 notes

·

View notes

Text

the best thing about being alive on earth is that sometimes there is a kitty

119K notes

·

View notes

Text

[empirical and easily verifiable claim about a work of art], but that's just my interpretation

31K notes

·

View notes

Text

The weirdest guy I ever met in a church was this boy who referred to “Buzz Aldrin and his husband” going to the moon. I was completely baffled, and when I asked if he’d misspoken, he got really angry and accused me of being deliberately ignorant of the facts. It turned out that he was somehow comvinced that Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong were married. It took five Wikipedia articles to convince him otherwise.

243K notes

·

View notes

Note

I was wondering how you feel about people writing fanfiction of your works, there's not a lot out there but they are some fun stories inspired by your own on Ao3.

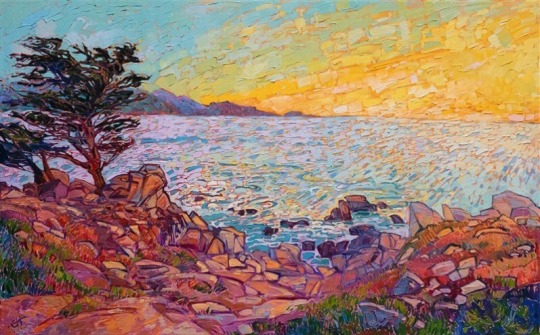

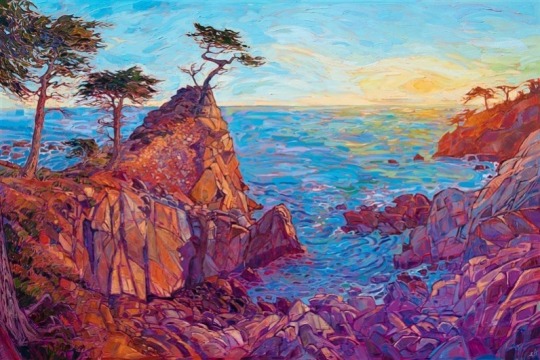

once an artist puts their art onto this timeline it begins to change and bloom and grow in unexpected ways. that is the wonderful thing about the trot of a writer or painter or director buckaroo.

fan fiction is just a part of the original art it is a flower blooming that i never knew was planted just an exciting seed that makes another flower then another until we have a garden that we are all sharing and watering together.

write all the fan fiction you want this proves love

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

When I make a map of a city, I spend some time learning about the place, its history, and the people who call it home. Over the past week I've been watching eruptions of police violence in so many of these cities, and more that I haven't had the chance to get to know. I've seen mass movements demanding justice for Black residents only to be teargassed, shot, and beaten.

People tell me that they buy my maps because they love their city. If you love your city, then you have to love its Black population, which has been suffering under racism from police (and civilians) for too long. If you're not Black, start by listening to your Black neighbors and following the lead of Black organizers. Support your local protests, by showing up on the ground, donating to bail funds, or some other way. Demand that violent and racist officers be held accountable. Insist on the de-militarization of police forces. Call for bloated police budgets to be redirected into services that support the community.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

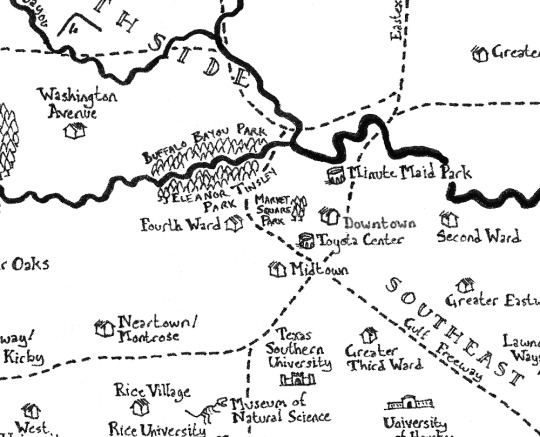

Fantasy map of Houston -- buy a print on Etsy

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mountains at the Edge of the Land

The release of the map for Robert Jordan’s posthumously published Warrior of the Altaii has gotten me thinking about a feature that is extremely common on fantasy maps -- the huge mountain range that forms the western or eastern border of the subcontinent where the story takes place.

There’s an obvious parallel between Altaii’s Backbone of the World and the Dragonwall in Jordan’s Wheel of Time series, but Jordan is not alone in using this feature. There’s the Westron Mountains in Stephen R. Donaldson’s Thomas Covenant series, Eridu from Guy Gavriel Kay’s Fionnavar Tapestry, etc. The wide-open plains of Rhun from Lord of the Rings don’t fall into this pattern (despite otherwise fitting the west/eastward-facing subcontinent model), though the Blue Mountains from the Silmarillion do. (Most of the examples that spring to mind are from the 20th century, and my impression is that fantasy worldbuilding has gotten more diverse in recent decades.)

The Eurocentrism of these classic fantasy geographies is often pointed out, and Europe does match the model in many ways, but Europe has no analogue for the mountains at the edge. Europe’s eastern side gives way to the extensive plains of Central Asia and Siberia. The conventional boundary between Europe and Asia is in the modern era usually placed along the Ural Mountains, but the Urals are no Spine of the World -- they’re quite modest as mountains go. Nevertheless, it could be that fantasy worldbuilders are being influenced by the concept of Europe being bounded by mountains.

I’m less interested in explaining this feature by finding real-world analogues than I am in thinking about what it contributes to worldbuilding -- the function it serves in stories. Here, I think the important thing to note is that in classic fantasy worldbuilding, mountains serve as barriers. Mountain ranges create lines that characters can’t easily cross, making for a challenge if they must cross it, forcing detours, and explaining why interaction between the places on either side is limited. (Note that this is not necessarily the case in the real world. From the mountain-centric empire of the Incas to the thriving trading communities of the Himalayas, mountains have often been just as much spaces of connection and exchange as barriers.)

A border range -- especially a very high one -- serves that bounding function for the land as a whole. But it’s a different kind of boundary than an ocean (which usually forms the side opposite the mountains). A mountain range signals clearly that there’s more to the world beyond it, but that that land won’t be playing a major role in the story (or if it does, it’s a story of contact between peoples who are ordinarily separate). A mountain range also gives the land a “back” side. Oceans are boundaries, but they’re also spaces of connection. We expect ships to be traveling up and down the coastline even if they don’t cross the open waters. A mountain range, on the other hand, does not facilitate travel along its length. The world in effect faces away from the great mountains.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

People who try to tell me things are ‘not that deep’ fundamentally misunderstand me, I am not a fish desperately in search of the ocean, I am a magpie that roves the canons, searching for shiny things to put in my nest. Whether or not it actually is given deep narrative weight by canon itself is of secondary importance to the fact that it has the potential to be interesting, and thus, I covet it.

144K notes

·

View notes

Text

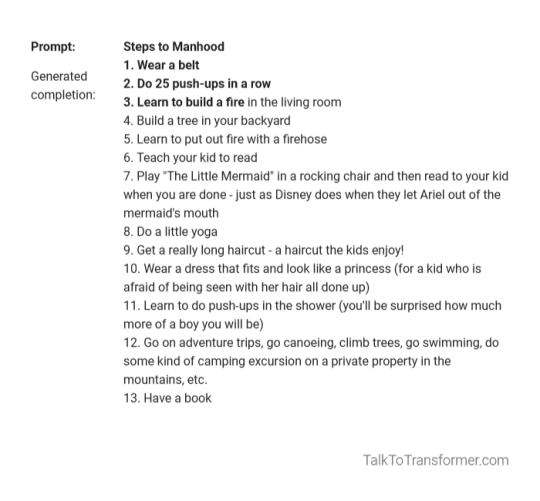

There’s a list of “99 Steps Toward Manhood” going around written by some conservative Christian. I decided to ask an AI for some advice on manhood by starting it off with a few items from the aforementioned list. I think the AI gives better advice overall:

41 notes

·

View notes

Link

I’ve been playing around with this AI that completes stories, and I fed it a few Tolkien starters:

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

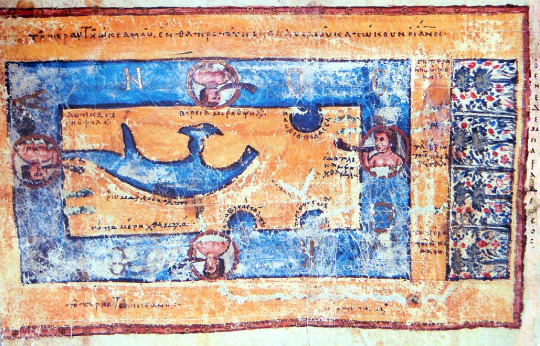

A flat earth proposal

Ancient flat earth theories envisioned the earth as essentially equivalent to a cylindrical projection of the real earth. This meant that E-W and N-S were both straight lines that remained at right angles to each other across the whole surface of the world. This is the simplest form of a flat earth model to construct. (map below by Cosmas Indicopleustes, one of the few medieval Westerners who actually believed in a flat earth)

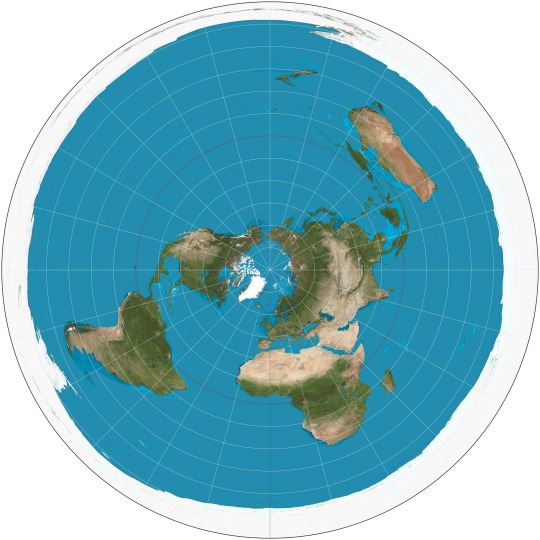

Modern flat earth theories most commonly envision the earth as matching an azimuthal equidistant projection centered on the north pole. This turns E-W into circles rather than straight lines, and makes N-S lines converge at the north pole and radiate outward to the south.

Compared to the ancient model, this modern model has several features that maintain its plausibility for flat earth believers:

1. It avoids interrupting the earth’s surface anywhere that people commonly travel. A cylindrical projection requires an interruption -- most commonly along the center of the Pacific Ocean, though you can in theory put it anywhere. But people travel east to west across the Pacific (and any other possible interruption location) all the time. You’re going to have trouble convincing someone who flew westward from California to Australia that their plane actually looped around eastward through the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, as would be required on a flat earth of the ancient model.

2. It maintains the connectivity of places around the Arctic. There is increasing travel through the Arctic (I flew across it in both directions on a recent trip from DC to Beijing and back to Chicago), which creates the same plausibility challenges if you’re using a cylindrical projection that ends at the arctic.

3. It can handle the fact (easily verifiable through telecommunications contact with people around the world) that the sun is always in the sky somewhere. The ancient model posited that the sun moved from east to west in a line across the earth, then returned by traveling beneath the world -- during which time the entire earth would have night. The modern model allows the sun to move in a circle above the earth, illuminating different areas like a spotlight.

But the azimuthal equidistant flat earth model presents some problems of its own. While sizes and shapes of land masses close to the north pole are not too wildly distorted, things in the southern hemisphere are way out of proportion. A flat earther using this model is committed to the claim that Australia is actually much, much wider from east to west than conventional maps would claim -- something that you’d think Australians themselves would have noticed. (Some flat earth maps correct for this by putting all of the E-W stretching into the oceans so that the southern continents stay the shapes we expect. Because this is an ad hoc correction of just the land areas, these maps never include a graticule whose inconsistencies would give away the game.)

The azimuthal equidistant model also requires positing that Antarctica is positively enormous, stretching around the whole outside of the world. Flat earthers have tended to make good use of this idea, by describing Antarctica as an impassable ice wall that separates us either from the void, or from unknown outer lands. But it’s still an awkward bit of geography.

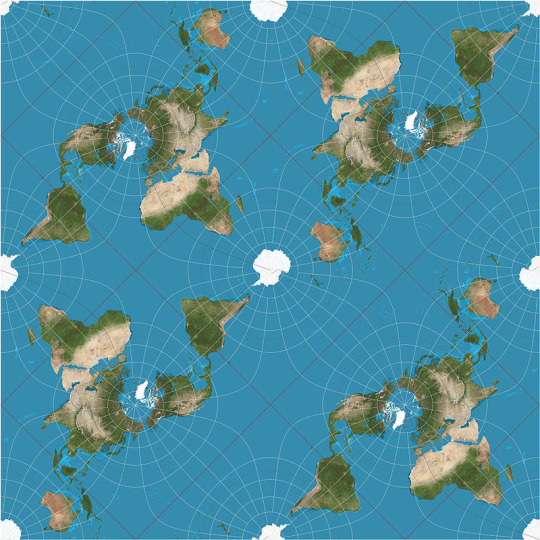

I want to propose an alternative flat earth model: an infinitely tiled Pierce quincuncial projection.

By bringing each corner back together in the south, this projection avoids the major southern hemisphere distortions of the azimuthal equidistant model. A single quincuncial earth would generate some issues of its own with the significant interruptions between the four lobes of the south, most notably breaking Antarctica into four pieces. But those problems can be solved by tiling this projection infinitely. If, for example, you travel to the part of Antarctica near South America and then begin to circumnavigate in an easterly direction, you would wind up in the southern Africa corner of the next world over. And since these different worlds are all precisely identical, your counterpart in another world would have just entered your original world’s Africa lobe, making it seem as if you had simply circumnavigated Antarctica on a round globe.

One seeming hitch to this model is what happens at the non-pole junctions. It seems as if on the tiled map you could set out due west from Ecuador and wind up in the adjacent world’s Ecuador, or likewise going south from India, etc. The thing to remember here is that when you cross the border between segments, your direction changes 180 degrees. Instead of going west from Ecuador in your original world, you’d suddenly be going east toward Ecuador in the next world. It’s the equivalent of getting unexpectedly turned around and heading back the way you came on the round earth. And since your counterpart from the adjacent world would be doing the same thing, there would be no apparent difference to anyone observing this, even yourself!

Because the quincuncial projection is a square, it also resolves the meaning of several Biblical references to the “four corners” of the earth, which have produced problems for biblical literalist flat earthers working with the clearly circular azimuthal equidistant model.

(Obligatory disclaimer: I’m a geography professor, so I obviously don’t actually believe the earth is flat, but I find examining the features of various flat earth models to be an entertaining intellectual exercise.)

24 notes

·

View notes