Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

RUSSIAN WRITERS AND POETS- Anna Akhmatova (1889 - 1966)

O let the organ, many-voiced, sing boldly, O let it roar like spring’s first thunderstorm! My half-closed eyes over your young bride’s shoulder Will meet your eyes just once and then no more. Goodbye, be very happy, I relieve you Of all your vows - but, dearest heart, take care Lest my most sacred words, my ravings fevered You breathe in your enamored partner’s ear. Know this: they’ll poison and corrode your ardent And blessed union… I go forth to seek - To seek and claim the lovely magic garden Where grasses softly sigh and Muses speak.

1921

The poetry of Anna Akhmatova can be called “the book of woman’s soul”. At the turn of the centuries – 19th and 20th, on the edge of the great revolution, in the epoch shattered by two world wars, there appeared, formed and developed perhaps the most significant female poetry in the history of the new time. Do we really need to distinguish between “male” and “female” poetry? Of course the great poetry is all-human, but it will hardly be possible to understand Akhmatova’s work not taking into consideration its female character. And the main explanation of it is in the world and Russian history itself – it was for the very first time that a woman had a poetic voice of such strength! Female emancipation expressed itself in poetic equality as well. “I taught women to speak”, - noticed Akhmatova in one of her epigrams.

Already in the 19th century there were a lot of women writing poems, and good ones, too, but still in general it was kind of “poetic periphery” and their names are now half-forgotten. Spiritual energy of woman’s soul that had been kept for centuries poured out during the revolutionary epoch in Russia in the poetry of a woman with a modest name – Anna Gorenko. Under the pseudonym of Akhmatova Anna gained world-wide recognition throughout her 50-year poetic career and was translated to all the main languages of the world.

Anna Andreevna Akhmatova (real name – Gorenko) was born on June 11th, 1889 near Odessa, in Bolshoy Fontan. While still very young, she was taken to Tsarskoe Selo(now Pushkin). She lived there until the age of 16, and it is there that she composed some of her first poetry.

She later graduated from an institute in Kiev, and it is here that her childhood romance with former Tsarskoe Selo schoolmate Nikolai Gumilev (later also one of the greatest Russian poets) finally culminated in marriage. During this time Anna had already written about 200 poems, some of which were selected for publication in her first book in 1912. The book, which was entitled Evening, brought her public recognition as well as critical praise. In 1914, Akhmatova’s second book, entitledRosary, was published. These first two compilations primarily contained psychological love poems. When reading these poems, you can see Akhmatova’s distinguished use of dramatic style and heartfelt emotional expression.

SONG OF A LAST MEETING

Though I stepped o'er the threshold lightly,

At my heart icy fingers clawed,

And the glove I wore on my right hand

On my left hand belonged, I saw.

Steps… so many, they left me panting,

But I knew there were only three.

From the maples there came a plaintive

Whisper autumnal: “Die with me!

I’m betrayed by my bleak, my changeful,

By my mischievous fate…” “I too!”

I replied. “O my love, my angel,

I will die, I will die with you…”

One last song, song of one last meeting…

Dark the house… I looked up, went on.

In the bedroom window a fleeting

Yellow light impassively shone.

1911

* * *

The cloud up in the wintry sky was furry,

A squirrel skin, pale grey, a trifle faded.

He said: “You know, I’m not the least bit sorry

That you will melt in March, my frail Snow Maiden.”

My hands turned cold inside the muff I carried…

Confusion came and fear, my heart ceased beating.

O how to get them back - that swift-gone, airy

Love and those weeks of it, so brief, so fleeting!

Hate? No. Revenge? What for? I’ll do without it.

O to be dead at winter’s end and buried!

On Twelfth Night, dazed, I asked the cards about him:

I was his love for most of January.

1911

Perhaps the greatest Russian poet of the “Silver Age”, Alexander Blok, was deeply impressed by Anna’s poetry, and after Blok’s death critics ranked her as the greatest Russian poet of her time after Blok.

Akhmatova’s third poetic compilation, White Flock was published in 1917, during the First World War. In this book, her sharp, ringing voice expounds upon the theme of her native land, Russia. At that time, a large portion of Akhmatova’s social relations, including close friends, began emigrating. The situation worsened, and Anna suffered a personal drama when she and Gumilev were divorced. Her only income was beggarly. In August 1921, Alexander Blok, who was by that time a great friend and teacher of Akhmatova, died, and then Anna learned that Gumilev had been shot. The shock was very deep. Anna wrote very little during this period, and it seemed to her that “the muse has completely abandoned my home” (from “The diary of A. Akhmatova”).

The early as well as late lyric of Akhmatova was closely connected with Blok. She was very often forced to explain that they were only connected poetically and not personally, and she humorously called these explanations “a story on how I didn’t have an affair with Blok”. But she did have an affair with him. Though it was an affair in verse – her muse was engaged to the muse of Blok. Why is it so you’ll ask. Because Blok’s poetic hero was the most significant and typical one in the Russian poetry of that time. Blok wrote on the books that he was giving to her simply: “From Blok – to Akhmatova”, and it meant “From equal – to equal”.

* * *

To Alexander Blok

When I came to see the poet

It was noon. The day was Sunday.

Large the room was, large and quiet;

In the street reigned frost… The sun

Was a crimson ball. Beneath it

Shaggy, dove-grey smoke went drifting..

Silent stood my host before me:

How serene, how clear his gaze!

Such his eyes that they who see them

Even once cannot forget them.

As for me, I would be safer

Had I met them not at all.

But I will remember always

What we talked about that Sunday

In the tall grey house that towered

By the gateway to the sea.

1914

And the most typical heroine was, of course, that of Akhmatova’s. She appeared before us in the greatest variety of woman’s fates – a lover and a wife, a widow and a mother, the one who cheated and abandoned and the one who was cheated on and broken up with… Akhmatova showed the whole complicated history of the female character in the times of crisis – its origin, its breaking and its forming anew. That is why her poems often seem revolutionary, though she refused to accept the Revolutions of 1917.

Akhmatova worshipped Alexander Pushkin. He was her another “poetic affair”. She was even “jealous” of his wife Natalie Goncharova though you know that Pushkin lived 100 years earlier than Akhmatova.

That is why Anna studied History and especially the history of architecture and art during Pushkin’s time. She studied his works as well; she desired to know them inside out. Her works on Pushkin are very well known in scientific world.

In the 1930’s, the “mysterious gift of song” came back to her quickly, and with a renewed strength, too. These years of her life were filled with great misfortune. Her son, Lev Gumilev (himself a well-known historian), was arrested and exiled due to the false accusation of being “the people’s enemy”, as was often the case with intelligent and talented people fallen under Stalin’s repressions. Many changes are noticeable in Akhmatova’s poetry at this time. Drawing from the breadth of her experience, Akhmatova’s poetic vision became much sharper and bolder. The collections Reed,Seventh Book, Shards, and a long poem Requiem (a very strong piece of poetry based on her experience as a mother of a repressed son), were published during this time.

During the Second World War, Akhmatova wrote Poem without a Hero, which saw publication in 1946. Later, a comprehensive compilation entitled The Race of Time. Poetry (1909 - 1965), was published. Her war poems are sharp and merciless, filled with hate of the Enemy. It was not in vain that she wrote afterwards:

THIS RUSSIAN SOIL

In all the world no people are so tearless,

So proud, so simple as are we.

1922

In lockets for a charm we do not wear it,

In verse about its sorrows do not weep,

With Eden’s blissful vales do not compare it,

Untroubled does it leave our bitter sleep.

To traffic in it is a thought that never,

Not even in our hearts, remote, takes root.

Before our eyes its image does not hover,

Though we be beggared, sick, despairing, mute.

It’s the mud on our shoes, it is rubble,

It’s the sand on our teeth, it is slush,

It’s the pure, taintless dust that we crumble,

That we pound, that we mix, that we crush.

But it’s ours, our own, and will open one day

To receive and embrace us and turn us to clay.

1961

The main moving force of Akhmatova’s poetry was love. In one of her poems, she called love “the fifth season”. She wrote that a human soul is alive

Not for passion, not for amusement,

But for dearest earthly love.

Her poems are very psychological. They are based on the Russian prose of the 19thcentury – Lev Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Leskov… Osip Mandelstam, another great Russian poet of the “Silver Age” said that Akhmatova developed her form and style looking back at the psychological prose. “There would be no Akhmatova, had it not been for Tolstoy and his Anna Karenina or all of Dostoevsky…”

* * *

A simple way of life I’ve learned and wise:

I watch the sky, and pray to God, and daily,

To tire distress, with promptitude unfailing

Take long, long walks before the evening dies.

When burdocks stir and sigh in the ravine

And rowans droop and bow their branches meekly,

I make up cheerful verses and serene

Of life, sweet life that passes all too quickly.

At home, the cat licks at my hand and fills

The quiet room with pleased and happy purring.

Up in the tower of the sawing mill

A single bright and steady light is burning.

A stork nests on the roof; its cry is queer

And rends the pregnant hush, deep and bewitching.

If at my door you knock, I will not hear:

The sound will die away and never reach me.

1912

Usually Anna’s poems are the beginning of the drama, or its climax, or only its end, - they are never a full story.

* * *

Each new day that comes the heart unsettles

More and more… How strong the smell of rye!

At my feet you have been laid, and that is

Where I’ll have you lie.

Orioles till nighttime from the very

Tops of maples call - loud are their cries!..

Oh, what fun to drive away the merry

Wasps that circle near your green, green eyes!

Do you hear a coach-bell’s far-off tinkling?

It’s a sound we both, my dear one, know.

Lest you weep, a little song I’ll sing you

Of a night of parting and of woe.

1913

In 1964, Anna was given the international poetic award “Etna Taormina” in Italy, and her historical research earned her an honorary Doctorate of Literature from Oxford University.

In her autobiographical notes in 1965, a year before her death, Anna Akhmatova wrote: “I am happy that I lived in this epoch and not another, and that I saw the events that have no rivals in history”.

Akhmatova is still the favorite poet of a lot of people, including me. She is worshipped here in Russia and especially in St. Petersburg where she lived for a great part of her life. On the bank of the Fontanka river there is a house that is called “the Fontanka House” (“Fontanny Dom”). This is a memorial museum of Anna Akhmatova, opened to the centenary of her birth in 1989. She lived in this house from 1926 to 1952.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

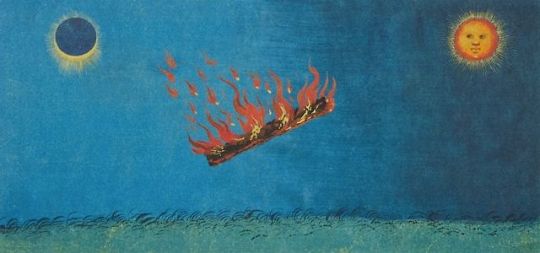

Das Wunderzeichenbuch (The Book of Miracles) Augsburg, ca. 1552.

22K notes

·

View notes