Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Chopin's monument in Warsaw, Poland

Polish vintage postcard, mailed in 1933 to Grenoble, France

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

'george sand's garden at nohant,' eugene delacroix, c. 1840s.

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) drawing of a tiger, next to 14 notes written on a scrap of paper by his friend Frédéric Chopin.

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

EDIT: UPDATED LINK URGENT SUPPORT REQUIRED

PLEASE READ ALL THE WAY THROUGH—UPDATED 31 May 2025

Due to outrageously high processing fees, the family seven-year-old Omar still has not raised enough funds to do Omar’s complete skin graft.

Now, they are trapped near Jabaliya by IOF attack. They need to arrange transportation out of the area NOW to avoid being killed by IOF death squads! They cannot move by foot due to their injuries, they NEED transportation out of the area NOW!!!**

Current: $0 usd

New temporary goal: $1,500 usd

Need to raise: $1,500 usd

More information in this thread.

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

funny how they always have him bending over (he's 6'3) yet they... nevermind.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

amadeusheads are you out there

alt and little wolfie under cut

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

just wanted to draw the gang in a silly pose :>

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Author: fraumozart

Rating: Teen and up audiences

Category: M/F

Fandoms: Classical Music RPF

Relationship: fem!Frédéric Chopin/Franz Liszt

Additional Tags: Hurt/Comfort, Drama & Romance, Love Confessions, Modern Era, Sexual Tension, Teacher-Student Relationship, Age Difference, Emotional Hurt/Comfort, Mutual Pining, Not Actually Unrequited Love, First Time, Emotional Sex, Jealousy, Liszt is very charismatic, Chopin is down bad, Their conversations are basically foreplay, Eye Contact

Summary:

Chopin suddenly sat up on the bed. Her heart skipped a beat.

From: [email protected]

Subject: Re: On the Romantic Form

Frédérique stared at the sender’s name for a long time, barely breathing. Her fingers froze on the trackpad. Chopin knew she had to open the email, but for some reason she couldn’t bring herself to—god, she hadn’t even expected him to read it, let alone reply. For a moment, the screen blurred before her eyes. She blinked. The name was still there.

or

Modern!AU, where Liszt teaches at a conservatory, and Chopin is a gifted, but hesitant student who struggles with her growing obsession.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/65610436/chapters/168927307

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

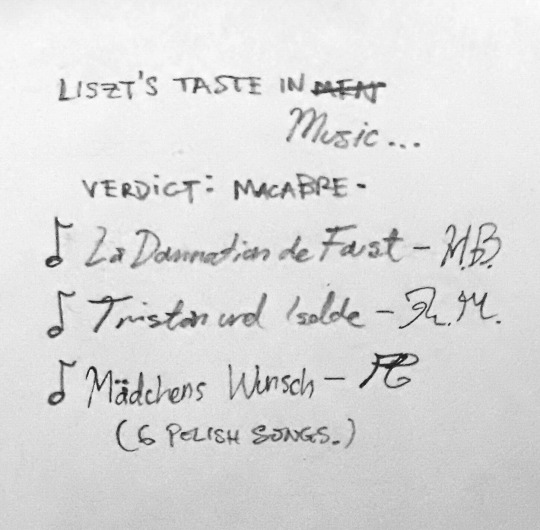

hihihi do you have any recs for sources to learn more about liszt, chopin, sand and delacroix? Although im a Nerd theres still stuff i dont know but i dont know where to start from </3 also question since i think you know more than me . Did liszt and george ever gang up to bully chopin [jokingly/affectionately].....

hi hi hi helloo!! I'm not a historian BUT I can give you some sources that I have used.

for liszt, I'd recommend alan walker's liszt biographies- he goes into so much depth about the man :)

for chopin, it's very easy to learn about his life when you read his letters (which are on the internet archive iirc)- but the chopin institute has a wealth of information about him >.<

for delacroix, a book called 'world of delacroix' (also on the internet archive) gives a really good overview into his life, and so is his Journal!! his journal is probably the best thing you could read to know about him. He mentions sand and chopin a Lot. The musee delacroix has a fantastic archive too!

finding really good sources for sand is tricky BUT again her museum is a great jumping off point...Im sorry I don't know as much about her </3 but maybe some other romanticism fans on tumblr can help ??

#franz liszt#fryderyk chopin#george sand#eugene delacroix#other people on tumblr pls help us out ...#classical music#classical composers

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

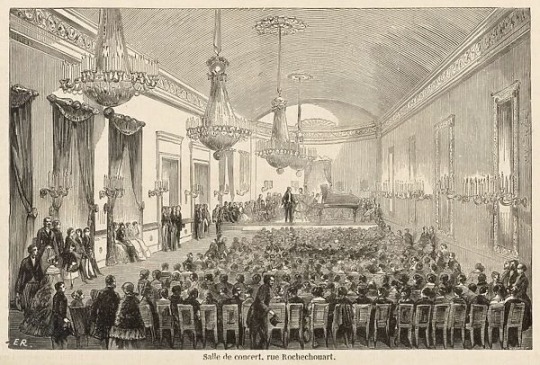

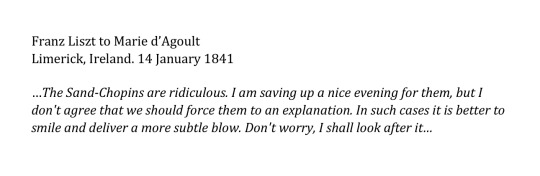

A ‘Majorcan’ Concert at the Salle Pleyel

Including a review by Franz Liszt (or Daniel Stern)

Salle de Pleyel, rue Rochechouart. Pre-1855.

On the 26 April 1841, I gave a concert at the Salle Pleyel in Paris. Also participating were two other artists, the violinist Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst and the soprano Laure Cinti-Damoreau, who performed between my pieces. The concert was given the epithet ‘Majorcan’ given that the programme included many pieces composed during my winter there with Sand. The programme included my Préludes op.28, Scherzo in C# minor, Polonaise in A major, Ballade in F major, mazurkas, etudes and nocturnes.

The audience was filled with the elites of the art world, including many of my acquaintances such as Berlioz, Liszt, Kalkbrenner, Mickiewicz, Heine, Delacroix, as well as the critics Ernest Legouvé and Léon Escudier.

Maison Pleyel Hall, Édouard-Antoine Renard. 1855.

From the concert, I earnt 6,000 francs, 6x the average annual income of a working-class family at the time. Ridiculous, perhaps, but it certainly kept me very comfortable over the summer.

Personal Affairs

In the months prior to the concert, there had been tension brewing between Liszt’s paramour, Marie d’Agoult, and my own partner, George Sand.

D’Agoult believed Sand had feelings for Liszt and was starting to dislike her brusque and promiscuous behaviour, while Sand found d’Agoult's fastidiousness irritating. D’Agoult supposedly sent unflattering letters about Sand's promiscuity, creating a rift between the friends. Meanwhile, having travelled with both d’Agoult and Liszt to Switzerland, Sand had been inspired by the story of d’Agoult fleeing her aristocratic, but stifling husband in favour of an affair abroad with Liszt. The story would have made a great novel, but as Sand was friends with d’Agoult, she gave the novel idea to Balzac.

In 1839, Balzac published "Béatrix," portraying both d’Agoult and Liszt in a cruel manner. (George later published "Horace," anyway, which told a similar story, depicting d’Agoult unfavorably). By the end of the year, d’Agoult and Sand’s friendship had completely broken down, with each feeling wronged by the other.

Nowadays, their quarrel leading up to the Majorcan Concert can be read in private correspondence:

With this in mind, I was quite disappointed when I found out Liszt would be reviewing my concert, not Legouvé, who had been my first choice.

When Legouvé told me this news, I replied, “I wish it were you.” To which he said, “You don't mean that, my dear friend! An article by Liszt is good fortune for the public and for you. Trust his admiration of your talent. I promise you he'll make you a beautiful kingdom.” “Yes,” I smiled, “In his empire!”

As frustrated as I was, Liszt was there on the night of the concert, watching avidly.

Below I provide a translation of his article.

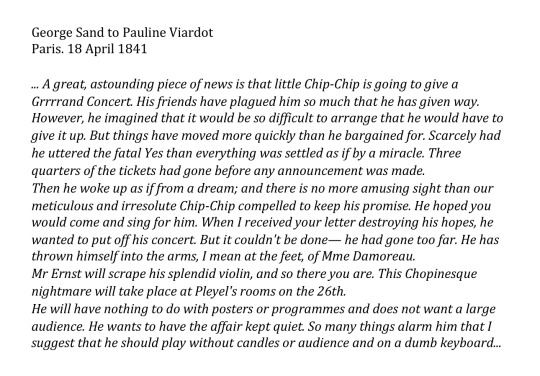

Concert at Salle Pleyel • 26 April 1841

— Review by Franz Liszt.

Review of Chopin’s concert by Franz Liszt. 2nd May 1841. Gazette Musicale.

CHOPIN’S CONCERT

Last Monday, at eight o'clock in the evening, M. Pleyel's rooms were splendidly lit; numerous carriages were constantly bringing the most elegant women, fashionable young men, celebrated artists, richest financiers, and the most illustrious noblemen to the foot of a staircase, which was covered with carpet and perfumed with flowers. A whole social elite, a whole aristocracy, by blood, money, talent, and beauty.

A grand piano was open on a platform; everyone crowded round, eager for the closest seats; they settled down to listen, they composed themselves, they said to themselves that they must not miss a chord, a note, an intention, a thought from he who was going to sit there. And they were right in being so eager, attentive, and religiously moved, because the man for whom they waited, whom they wished to see, hear, admire, and applaud, was not only a skilled virtuoso, a pianist, expert in the art of note-making, not only an artist of great renown, he was all this and more, he was Chopin.

Arriving in France around ten years ago, Chopin, among the crowd of pianists who at that time were flocking from all parts, did not fight to obtain the first or the second place. He seldom played in public; the famously poetic nature of his talent did not lead him that way. Like those flowers, which only open their fragrant chalices in the evening, Chopin required an atmosphere of peace and reverence to enable him to freely pour forth the treasures of melody from within him. Music was his language; a divine language, in which he expressed a whole array of feelings that only few could understand. Just like that other great poet, Mickiewicz, his compatriot and friend, the muse of his homeland dictated his songs, and the sorrow of Poland lent a kind of mystic poetry to his music which, for those who have truly felt it, is incomparable. If less brilliance has been attached to his name, if a dimmer halo has encircled his head, it is not because he did not have in him perhaps the same energy of thought, the same depth of feeling as the illustrious author of “Conrad Wallenrod” and the “Pilgrims”; but that his means of expression were too limited, his instrument too imperfect; he could not, with the simple aid of a piano, reveal his entirety. That is, if we are not mistaken, a dull and continued suffering, a certain repugnance to communicating with the outside world, a melancholy which hides itself under apparent gaiety, ultimately, an entire personality, remarkable and charming to the highest degree.

As we have just said, it was only rarely, between long intervals, that Chopin played in public; but what would have been an almost certain cause of oblivion and obscurity for anyone else was precisely what ensured that his reputation stayed above the caprices of fashion, and sheltered him from rivalry, jealousy, and injustice. Chopin, separate from the exaggerated shift which for several years has thrust performing artists from all corners of the world on each other and against each other, has remained constantly surrounded by faithful followers, enthusiastic pupils, and warm friends, who, all while guarding him against quarrelsome conflicts and painful frictions, have never stopped spreading his works, and with them, the admiration for his genius, and respect for his name. Thus, this refined celebrity, at the top of his game and aristocratic to the core, has remained untainted by any attack. There is already a complete silence from the critics around him, as if posterity had come; and in the brilliant audience which rushed to hear the too-long-silent poet there was neither reticence nor restraint, unanimous praise was on the lips of all.

We are not going to undertake here a detailed analysis of Chopin’s compositions. Without any feigned quest for originality, he was himself, both in style and approach. He knew how to give new thoughts a new form. This wild, abrupt thing belonging to his country, found its expression in daring dissonance, in eerie harmonies, whilst the delicacy and grace of his person were revealed in a thousand contours, in a thousand ornaments of inimitable fantasy.

At Monday's concert Chopin favoured those of his works that are farthest removed from classical forms. He played neither concerto, nor sonata, nor fantasies, nor variations, but préludes, études, nocturnes, and mazurkas. Addressing himself to a private circle rather than to a large audience, he could, without punishment, show himself for what he is: an elegiac, profound, chaste, and visionary poet. There was no need to either astonish or overwhelm; he sought for delicate sympathy rather than for noisy enthusiasm. And, let us say at once, that these sympathies were not lacking in him. From the first chords he had established a direct communication between himself and the audience. Two études and a ballade were encored, and had it not been for the fear of adding to the already great fatigue which betrayed itself on his pale face, the crowd would have asked for all the pieces of the programme again, one by one.

Chopin's Préludes are compositions of an entirely different species. They are not merely, as the title would suggest, pieces to be played as introductions to other pieces — they are poetic preludes, comparable to those of a great contemporary poet, which lull the soul into golden dreams, and elevate it to the most ideal regions. Admirable for their variety, the work and knowledge that are found within are appreciable only after a scrupulous examination. There, everything is gushing, bursting, unexpected. The préludes have the freedom and great allure that characterises works of genius.

What can be said of the Mazurkas: little masterpieces, so whimsical yet so complete?

“A faultless sonnet alone is equal to a long poem”, said a man who was a leading figure in the finest century of French art. It would be very tempting to apply the same exaggeration of this axiom to the Mazurkas, and say that to us, at least, many of them are equal to very long operas.

After all the applause lavished on the king of the fête, M. Ernst also received some well-deserved praise. He played an elegy in a large and grandiose style, with passionate feeling and a purity worthy of masters, thus heartily impressing the audience.

Madame Damoreau, who had lent her charming assistance to this concert of fashion, was, as usual, ravishingly perfect.

One more word, before ending these lines which we are forced to cut short for lack of time.

The fame or the success which crowns talent and genius, is, in part, the product of favourable circumstances. In truth, lasting fame is rarely undeserved. Nevertheless, as fairness is perhaps the rarest quality of the human mind, certain artists find their success falls short of their true worth, whilst for others, it exceeds it. It has been observed that regular tides always have a tenth wave stronger than the rest; thus, in the way of the world, there are some men who are carried along by this tenth wave of fortune, and who go higher and further than others, their equals, or even their superiors. The genius of Chopin has not been aided by these particular circumstances. His success, though very great, has remained short of what it should be. However, we say with conviction, Chopin has nothing to envy. The noblest and most legitimate satisfaction an artist can have, is to be above his reputation, superior even to his success, greater still than his glory, is it not?

Betrayal?

Perhaps due to Liszt’s virtuosic reputation and my own jealousy, what happened next was painful for me. Lisztomania was spreading like a disease, whilst my own sickliness confined me to the indoors with little desire to perform. Whilst I floundered in the wake of Liszt’s popularity, an article had been written that appeared to me a betrayal. Whether it was written by Liszt or d’Agoult means little to me — Franz still allowed it to be published under his name. This article which omitted any reference to the virtuosic pieces and epic works that I had played on the night. Instead, the author wrote of the 'miniatures' on the programme — my preludes and mazurkas. Thanks to this, I was consigned to role of an aristocratic salon pianist. I was dainty, weak, effeminate according to Liszt: a notion he perpetuated even after my death.

Worst still, was that his treatment of me had been noticed by the press. It was an embarrassment.

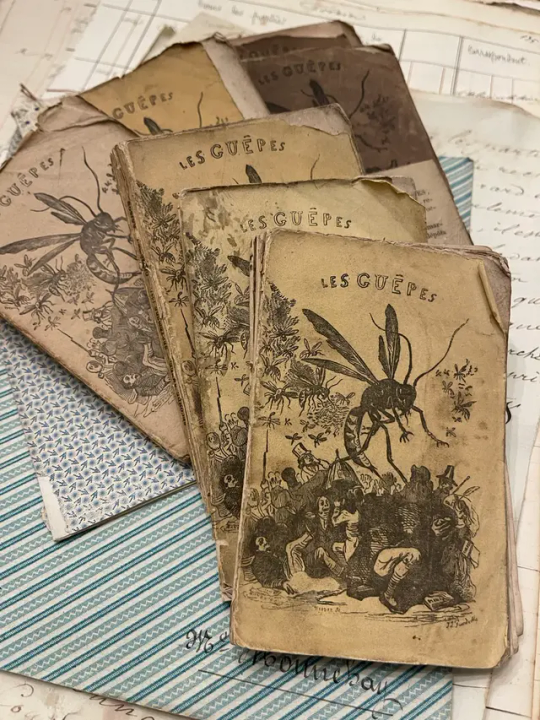

Les Guêpes. 1841.

Les Guêpes, Alphonse Karr. 1st May 1841. pp 60-61.

The satirical journal, Les Guêpes, wrote about Liszt’s role in the concert, which I will translate below:

Nowadays pianists play more for our eyes than for our ears, and pound the keyboard as though afraid that otherwise we would not know it is wooden. Almost every time M. Listz plays, a piano dies. At the last performance, he played standing up; he will play lying down next. But what do you want these poor devils to do, praise is their downfall. Lately, a man who is usually witty, said that he liked to see a pianist panting. It happens very often that M. Listz, when he has just performed his breathtaking music, finishes by letting himself fall unconscious onto his piano. This is entrancing.

At M. Chopin’s concert, which I did not attend, I was told that, once the piece was finished, M. Liszt, who was not playing the piano, but who insisted on playing some role, rushed towards M. Chopin to support him, thinking that he would faint.

Aftermath

Whilst the intentions of the article cannot be known for certain, d’Agoult’s letter to Liszt on 7th May 1841 reveals her pleasure that:

“The intention and performance of the Chopin review continue to be regarded as admirable.”

Equally, d’Agoult’s determination to no longer associate with Sand and I is evident in the following letter. Her argument with Sand had left her bitter and malicious.

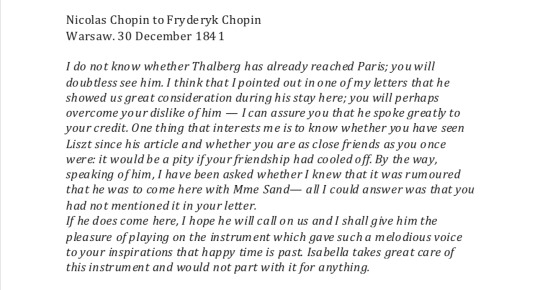

Although some point to other events as a cause for tension — such as when Liszt embellished one of my nocturnes in 1843, and the time he used my apartment for an affair in 1835 — it is clear that this concert was the pivotal moment. As is evident in the following letter, even my father was aware of the rift.

Conclusion

I hope this clears up any uncertainty regarding mine and Liszt’s relationship. Whilst we were initially good friends, our relationship deteriorated, largely due to his concert review, as well as tensions between our partners.

We still maintained a relatively civil relationship, and following my death, Liszt played a large role in the memorialisation of both me and my music. His biography, Life of Chopin, was first published in 1851 in La France Musicale. Although this in itself was controversial among some of my closest friends for the invasive questions Liszt had aimed during his research for the biography. Likewise, the biography is notable for its romantic and sensationalist tone, which further depicts me as a delicate “convolvulus” in contrast with Liszt’s passion and energy.

Personally, I rejected and still reject being consigned to this role. But it is up to the reader to decide whether there is right or wrong in this business, for I came to my conclusions almost 200 years ago.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue of George Sand in the Luxembourg Gardens of Paris

French vintage postcard

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

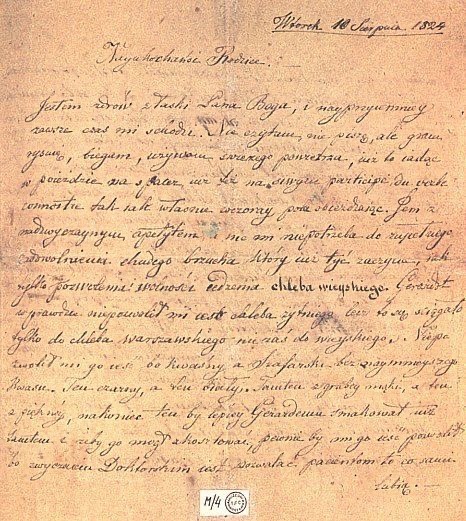

Letter by Fryderyk Chopin to his family in Warsaw,from Szafarnia, 10 August 1824.

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

WAIT I NEED YOU TO SEE MY VISION

These two are the choliszt moths to me . The right one, and emperor moth, is liszt and the left one, a box tree moth, is chopin . They even have the accurate height/size difference [i think emperor moths have 50-60mm wingspan while box tree moths have 40 mm]

OP. YOUR BRAIN. I see the vision yes THIS IS FANTASTIQUE!

#franz liszt#fryderyk chopin#did you know I once had an obsession with moths#thus my name is atlas. because of the moth

5 notes

·

View notes