Text

Hi Kate,

What an insightful post! It’s really interesting to hear you reflect on your reasons for entering the field of environmental science and your background in finance. I agree with you that it is certainly going to be a huge challenge to ensure companies engage in huge changes to their sustainability and environmental practices on a local and global level. As you say, the capitalist, globalized society that we are living in, which continues to be fuelled by consumerism, is posing a huge obstacle to ensuring that such transformations occur.

I really resonate with your personal ethic, that we have a responsibility to engage all people and sectors of society in interpretation in order to ensure we successfully address the number of threats to our environment and the future of humankind. I too felt a sense of hopelessness when I first discovered the sheer magnitude of the environmental crises we face, particularly climate change. However, as you say, the attention given to these issues has certainly increased in recent years and there are a number of actors and organisations attempting to ensure social and environmental changes are enacted in response to them. The quote you cited by Tom Merriman really connected with me; I certainly agree that we have a responsibility as interpreters to communicate how our everyday behaviours contribute to these global issues. Extending on this, I feel that we must also communicate the social and environmental injustice that is associated with these issues, particularly with concerns to climate change.

Like you, I also feel that we must encourage children and adults to give back to nature within our approach to interpretation. As you say, empowering individuals to engage in environmental stewardship activities in their local community is an essential element of interpretation. Indeed, appreciating and connecting with nature can begin with our own localities; once this sense of care and responsibility is extended to these locales, it can then be nurtured and extended to our global environment.

Thank you so much for sharing this- I wish you all the best in your future!

Mia

Unit 10 Blog – Nature Interpretation: Personal Ethics & Beliefs

In our final concluding blog for this course, I find myself going back to the beginning, not the beginning of the course, but to what started me on my decision a year ago to take time off from a career in finance, to study environmental science at this university. Having worked in corporations for over 27 years, I have seen first-hand, how difficult it is to convince executive leads, board members and shareholders on the relevance and urgent need to become more sustainable, to care about the environment. Especially, when at times, I helped model the trade-offs of investment in other competing initiatives, with far higher immediate returns. During that time, we have come a long way, and many of those same companies now have ESG strategies (Environment, Social, Governance), and have even hired small teams to lead the way forward in becoming more sustainable. At the same time, many of those corporations have grown 5-10 fold or more, the growth of these companies, along with the emissions, waste, resource use and pollution generated, cannot be covered off with their new (at times) tepid sustainability goals. Now…these companies are not solely to blame, there is a demand fueled by population growth, global world development, and by increased consumerism in developed countries.

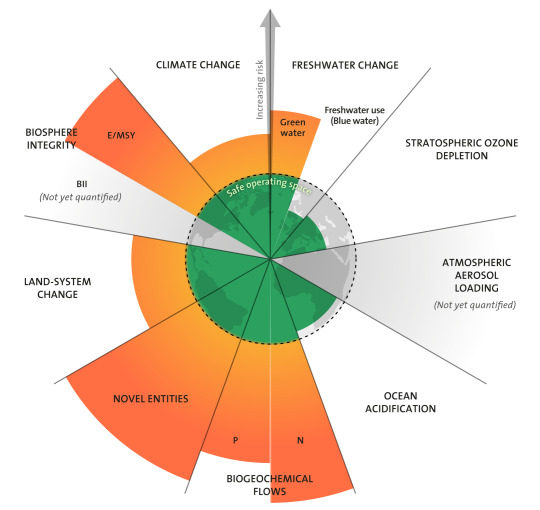

My reason for studying environmental science, is the same fuel for my personal ethic: More is needed, and until we change the minds of governments and corporations, and most importantly, the voters, consumers, employees, and shareholders, we will not succeed. My personal ethic is this: We all have a responsibility to learn, to teach, to engage others to see the scientific truth about our world and we are running out of time. To do this, we need to engage humankind to understand why it is important to protect nature, and why nature is so important to all species. Tim Merriman writes, "We still need to help the world’s decision-makers understand the vital importance of the effects we have on the Earth’s atmosphere and ocean, and we must continue to help all people understand how individual behavior contributes to both the problems and the solutions.” (Beck, at al., 2018, pg. 459) As per the Stockholm Resilience Center, we have the left the safe operating zone for 6 out of 9 of our planetary boundaries. (Stockholm Resilience Center, 2023). When I read this a year ago, I was shocked, and panicked and felt helpless against this. At the time, however, I did not understand how much is being done by so many globally to reverse the tide. I had heard about the Paris Climate Accord, and although a positive step, it was not going to be nearly enough. At that point, I hung my head thinking once again, politicians are going to get this wrong. In November 22, under COP-27 (The 27th Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change), more was done, and funds committed to help vulnerable nations as they become the first to feel the ravages of climate change. I am more hopeful, and I believe that the world has woken up to climate change. However, there is still much to do and to turn the tides of public neglect, disregard, or negation of the seriousness of the situation, we must not only open their hearts but also create a path of possibility that has us all believing that we can make a difference and that we can bring our home back from the brink.

Stockholm Resiliency Center 2022

Nature Interpretation for me, is one path to bring people into nature, with a feeling of safety. To let them see and appreciate not only the peace, beauty, and awe of it, but to understand the importance of it and the threats to it. This would be my focus or first responsibility in interpretation. To do this, it is also an interpreter’s responsibility to know the subject matter, and to engage the audience, while ensuring that everyone’s needs and pre-existing beliefs are considered. Nature must be inclusive, to be reflective of the world we live in. Richard Louv writes, "Interpretation enriches experiences, advances physical and mental health, benefits the environment, promotes cultural heritage, enhances community welfare, and recognizes the importance of diversity, equality, sustainability, science, and truth" (Beck et. al, 2018, pg. 476).

My approach would be to balance between finding ways to engage through humour, fun, and instilling a sense of adventure, but tempering that with the goal to engage children and adults to understand the importance of giving back. In Chapter 21 of our text, there were many examples of how we can become more involved even just in a small way, by understanding our own localities. Enos Mills wrote, “"A nature guide in every locality who, around his home or in the nearest park could show with fitting stories the wild places, birds, flowers, and animals, would add to the enjoyment of everyone who lives in the region or who visits it.” (Beck et al., 2018, pg. 458).

In listening to the interview with Richard Louv and David Suzuki at the AGO, a few other thoughts were enforced. One, many people, by choice or circumstance have become very disconnected from the natural world, seldom leaving the comfort of their homes and screens. To reach these people, more must be done to build urban parks, or reach out through technology to get their attention to get out and “smell the roses”. Two, as David Suzuki said, we have really become time machines (and not in a good way), we control our time slots and fill them up, but that is not natural. As he speaks, “Nature needs time to reveal her secrets.” He speaks to the need to just spend time, whatever time watching and immersing ourselves. I think a disconnect from nature hurts humans, we need nature to remind us of where we came from, we need nature to help us rebalance and breathe. We need nature to feel awe, to really be inspired.

In closing, I go back to the beginning, we must appreciate the home we have, and live with an eco-centric mind set, while understanding, that we have a job to do to keep our home for future generations. Stan Lee in Spider Man wrote, “With great power, comes great responsibility”.

References

Beck, L, Cable, Ted T., Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting Natural & Cultural Heritage. Sagamore-Venture Publishing. 2018

Stockholm Resilience Center (2023). Planetary Boundaries. Stockholm University. https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

Richard Louv and David Suzuki at AGO. https://youtu.be/F5DI1Ffdl6Y

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Aaliyah,

I really enjoyed reading your post this week! I definitely resonate with your reflections about what you’ve gained out of taking this course, particularly how your perspectives have been broadened with concerns to the different lenses through which we can engage learners in nature interpretation! (Beck et al., 2018).

All of the characteristics that make up your personal ethic are really important; I too believe in the importance of maintaining optimism and hope with concerns to the future of our natural environment. I agree with you that sometimes the negativity that we are surrounded by in today’s world relating to major environmental crises like climate change and biodiversity loss can become really overwhelming to both interpreters and audiences alike. In order to encourage our audiences to want to make a change in the world, we must inspire a sense of hope in achieving a future in which both our own species and the natural environment around us thrive! We can sometimes feel powerless when confronted with the sheer magnitude and severity of these issues. However, we must remind our audience that there is also a sense of hope and excitement that must dominate our visions for the future; we have an opportunity to ensure a better future for our world and this is an exciting prospect that we cannot lose sight of!

I also really resonate with your point about our responsibility, as interpreters, to provide an experience that is both relevant and meaningful to our audience. By catering our content and delivery to them, we can maximise our audience’s engagement in this process of interpretation and hopefully inspire a sense of environmental appreciation and stewardship among them.

It sounds to me like you have a really strong passion for interpretation and I wish you all the best in your future endeavours!

Mia

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Personal Interpretation. Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for A Better World.

Developing as a Nature Interpreter: Prioritizing Responsibility, Passion, and Hope- Unit 10

The content of this course has given me a comprehensive understanding of the role of a nature interpreter. I have also learned to broaden my perspective on nature by viewing interpretation through different lenses, such as art, science, history, music, and technology. Although it has been challenging at times to see from these different perspectives, this course helped me to understand my passions, interests, and the motivation that contributes to my appreciation of nature. I have learned a lot about how I can share my love for the environment with others and help people understand the value of our ecosystem. Through teaching these values to others, we can address and achieve the changes necessary to maintain the world we all love.

Through considering these values and outlooks, as I develop as a nature interpreter, the personal ethics or characteristics of myself I would prioritize are perspective, optimism, confidence, motivation, commitment, environmental concerns, and dedication to providing knowledge to promote environmental preservation. These values are essential in nature interpretation, as are equity, respect, and honesty.

The textbook by Beck et al. (2018) has taught many ways to serve as an interpreter. We have all learned many of the do’s and don’ts and most effective ways to get our values and points across to an audience, but the overall point is the responsibility we have as interpreters. Interpreters have many responsibilities. It is an interpreter's responsibility and privilege to educate the audience by providing accurate, professional material that makes the experience relevant and rewarding to the audience (Beck et al., 2018, p.136 & p. 332). Thus, as an interpreter, I would value the responsibility of communicating relevant, accurate, reliable scientific information about nature and the environment to the public. To do this, I would need to be confident in the information I know, find scientific studies, and constantly update the information I am providing my audience. Secondly, I would prioritize the type of environment I am creating. I would want the experience to be engaging, meaningful, and comforting for everyone present. This would include interactive programs that engage the audience to pay attention and also enjoy the experience. For an audience to feel inspired, the program must include all individuals present to be effective at engaging the audience in a positive experience (Beck et al., 2018, p. 128). Lastly, I would be sure to advocate for nature conservation and sustainability. Sharing the importance of protecting the environment is essential for visitors to adopt responsible behaviours to make a change.

A specific approach I would find most suitable for me as an individual is for interpreters to give their audience time to take in the information provided and discover their personal options on the topic. Both Mills and Tiden mentioned that interpretation is sometimes more effective in silence (Beck et al., 2018, p.83). An interpreter conveying the beauty of a scene might limit the individual's own inspiration (Beck et al., 2018, p.83). Thus, as an interpreter, I would allow for some scenes to speak for themselves so that the audience sees the beauty in their own way. This approach helps to formulate a sense of gratitude and serenity that is individualized and authentic.

When considering becoming an interpreter in the future, I have thought about feelings of discouragement and how they may be difficult to overcome. It may be challenging to facilitate meaningful connections between nature and people when there is so much negativity in the world we live in. For example, climate change, deforestation, habitat destruction, water and air pollution, biodiversity loss, and many more issues make people feel helpless. Jacob Rodenburg demonstrates this situation by stating: “I’m trying hard not to get discouraged. Being an environmental educator in today’s world feels like you are asked to stop a rushing river armed only with a teaspoon” (Rodenburg, 2019). It is important to not dwell on the negativity but to focus on your passion in forming solutions to the problems the environment faces. This motivation is absolutely essential for interpretation because if the interpreter is not passionate about the topic and motivated to better our futures, the audience will not feel this way either.

A quote from the textbook by Beck et al. (2018) discusses the need for hope in interpretation:

"Lighthouses are beacons of guidance and hope. Interpretive sites are also beacons of hope that help people find their bearings and keep them on course…Interpreters are stewards of areas that provide a sense of place and meaning. Each day it is the interpreter’s responsibility, privilege, and joy to thus illuminate the world. Lighthouses, in this broadest sense, provide authenticity for where we are in a complex world. Perhaps they are most needed in dark, stormy times to guide people away from danger and provide a sense of security and stability."

As I develop as a nature interpreter, I must develop a sense of hope and optimism and feel it is possible to improve the ecosystem despite challenges. I must sincerely believe in the lessons I teach and my impact on my audience. By doing so, the beauty of nature can be shared with my audience and they will develop the same feelings of hope and optimism. Thus the audience will appreciate nature and become motivated to take action to protect and improve the environment.

In conclusion, this course has given me a comprehensive perspective of the responsibilities and roles that come with the interpreter position. I have learned how to effectively teach an audience the value of nature and to protect the environment we live in. I learned the various lenses nature can be interpreted from and have a new view of the ways in which we can teach audiences. I have also learned a lot about myself. I learned my values and what ethics I must prioritize, the reasons for my passion for nature, and the parts of nature I love most. Despite the challenges an interpreter might face in a world full of environmental issues, it is essential to maintain a positive attitude to serve as an effective teacher. Overall, by carying out these responsibilities and positivity, meaningful connections between people and the environment can be obtained and serve to better the environment we all love.

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Personal Interpretation. Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for A Better World.

Rodenburg, J. (2019, June 17). Why environmental educators shouldn't give up hope. Environmental Literacy. https://www.naaee.org/eepro/blog/why-environmental-educators-shouldnt-give-hope

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nature Interpretations Role in Environmental Sustainability

Nowadays, it is becoming harder and harder to maintain a positive outlook on the future of our species and the planet. Admittedly, I am fearful for what might become of our ecosystems and future generations of people in light of the huge environmental and social crises that we face in the modern day. However, my personal ethic as a nature interpreter is centred around a sense of hope that as a human collective, we can better support one another and our surrounding environment today and in the future.

I feel that human-caused environmental issues have been and continue to be fuelled by our psychological and physical disconnectedness and isolation from our natural environment. As an interpreter, I want to help individuals to re-establish and strengthen their relationship with nature, to facilitate a deeper understanding and appreciation for the interconnectedness of all life on earth and our dependence on the health of our surrounding ecosystems.

My background in the International Development and Human Geography discipline has also deepened my belief in the importance of recognising the intertwined nature of environmental and social justice issues; we cannot address one without the other. Thus nature interpretation, particularly in Western nations, must reinforce the importance of understanding that our actions here have environmental and social consequences upon not only our local, but global environment. As Beck et al., (2018) highlight, nature interpretation must grapple with critical issues in our past, present and future on multiple scales; this includes the continued legacies of colonialism that persist in our current attitudes and management of our natural environment. Since being on my year abroad here in Guelph, I have been lucky enough to be able to study and explore some indigenous values, perspectives and ways of relating to nature. It is essential that nature interpretation recognises the importance of indigenous knowledge and understanding of nature in Canada and worldwide (Merenlender et al., 2016). I feel that the tendency to view nature as a natural resource for our use and exploitation has been the catalyst driving our degradation of nature. In order to raise the next generation of environmental stewards, as interpreters, we need to encourage learners to develop connections with the natural world that surpass the economic value of nature that continues to prevail in the capitalist society in which we live.

With this in mind, I feel a sense of responsibility to facilitate the growth of individuals’ personal connections to nature. Through taking this course, I’ve had time to reflect on the uniqueness of each of our relationships with nature, particularly through reading everyone’s blog entries. To be able to do this, we must get to know our audiences, including their beliefs, interests and values, to make our interpretation as relevant as possible to them (Beck et al., 2018). Our interpretive space should be a comfortable and familiar environment for all; we must remove social, physical and psychological barriers to maximise the inclusivity of this experience (Gallavan, 2005). We all learn differently and as interpreters, we are responsible for ensuring our content is inclusive of this diversity (Beck et al., 2018). Part of this also includes engaging in self-reflection on our own privilege and utilising multicultural approaches within our activities (Gallavan, 2005). In the future, I would love to have the opportunity to engage in nature interpretation and environmental education initiatives across the world, particularly in South America. In this context, I believe it is particularly important for me to engage in such reflections.

As an interpreter, I also feel a sense of responsibility to enable younger generations to connect with nature. Over the next decade, more and more of us will be living in urban cities; in light of this, interpreters must provide opportunities for children to have direct contact and experiences with nature when growing up in these spaces. Throughout this course, I have come to realise just how lucky I have been to grow up surrounded by nature; a child’s exposure to the natural world at a young age can be hugely influential in shaping their relationship with nature later in life (Beck et al, 2018). As society becomes increasingly more and more technological and structured, opportunities for unstructured play in nature must be given to children (Beck et al., 2018). Young children can begin developing personal and emotive connections to nature by exploring their local ecosystems (Rodenburg and Martin, 2019). Even in more urban areas, interpreters must show that elements of the natural world are still present amongst this man-made infrastructure. As Rodenburg and Martin (2019) suggest, interpreters can adopt the strategy of encouraging children to explore microenvironments, like the world of insects, in these urban settings. If we can bring children to nature, we can spark a sense of curiosity among them, which can give way to a sense of appreciation and love for nature as they grow older. In turn, this will act as the foundation for inspiring them to extend the same sense of love and responsibility to nature beyond their local environment, to their global environment.

East Sussex, United Kingdom.

East Sussex, United Kingdom.

Hence, I do feel that I have a duty to help the next generation to both connect with nature and understand the threats our world is facing, but also to empower them to take the action we need to address these threats. However, that’s not to say that as interpreters, we don’t have a responsibility to help encourage all audiences to connect, appreciate and protect nature. If anything, we have a responsibility to current generations of humankind and other natural organisms to reconnect and inspire stewardship among everyone that’s around us. Global environmental issues like climate change and biodiversity loss require an immense global response from all sectors of society right now. Human populations within Canada and beyond, particularly communities in lower-income countries, are already experiencing severe impacts of such environmental issues like climate change. Going forward into my career, I feel that I must help to resolve the barriers to science communication and provide an interdisciplinary approach to interpretation that’s engrained within concepts of sustainability. We need to recognise the importance of exploring critical conversations concerning the social and environmental injustices and inequalities underlying our current treatment of the environment (Gallavan, 2005). Particularly in the West, I feel that we have a long way to go in terms of taking responsibility as a collective for our environmental impacts in other nations and I believe nature interpretation is an essential part of inspiring social and political change.

Overall, this course has given me some really valuable insights into what it means to be a nature interpreter and I will definitely be integrating what I have learnt and the self-reflections I have engaged with going forward. I am proud to have a passion for appreciating and protecting both the natural world and one another. I know that it will be a lifetime goal for me to facilitate the same sense of love and intent for action amongst the people around me in whatever way I can.

Alberta, Canada.

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage : for a better world. Sagamore Venture.

Gallavan, N.P. (2005). Helping teachers unpack their “invisible knapsacks”. Multicultural Education, 13(1), 36.

Merenlender, A. M., Crall, A. W., Drill, S., Prysby, M., & Ballard, H. (2016). Evaluating Environmental Education, citizen science, and stewardship through naturalist programs. Conservation Biology, 30(6), 1255–1265. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12737

Rodenburg, J., and Martin, J. “Why Environmental Educators Shouldn't Give up Hope.” CLEARING, 2019 https://clearingmagazine.org/archives/14300.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Hrjyot,

I really enjoyed reading your post this week! I certainly agree that Jellyfish are fascinating oceanic organisms. Like you say, their bioluminescence can create fascinating displays of light and colour which can capture the attention and appreciation of all of us, no matter our scientific background. I really enjoyed the way you explain how jellyfish create this luminescence; I had no idea that this also serves as a defence mechanism for them!

You raise a really important point about the importance of Jellyfish to the wider ocean ecosystem; when engaging in nature interpretation, I think it's really vital to reinforce the importance of these species for other organisms and wider ecological processes. In doing so, a more holistic understanding of a species' wider ecological role can be conveyed, and how this in turn affects our own interactions with our environment can be reflected upon.

I had no idea that jellyfish have inspired such human technologies that you describe- I think this just goes to show how much we as humans have to learn from the natural world. Inspiring a sense of fascination and understanding of these creatures can definitely help individuals to extend a sense of appreciation and value to them, and therefore a recognition of the importance of protecting their habitat from harm. Out of interest, do you know what the most pressing threats are to these organisms currently? Are many Jellyfish species currently endangered?

It was really interesting to hear your knowledge of these organisms, thank you for sharing!

Unit 9 The incredible features of Jellyfish

This week we can pick a topic of our choice as long as it's amazing, and Jellyfish are nothing short of that. Jellyfish are fascinating creatures that have captured the attention and imagination of scientists and nature enthusiasts alike. They are unique because they have no brain, heart, bones, or eyes. Instead, their smooth, bag-like bodies and tentacles armed with tiny, stinging cells make up their anatomy. However, their ability to produce bioluminescence sets Jellyfish apart from other animals, creating a beautiful and captivating display in the ocean. Bioluminescent Jellyfish can produce light in various ways, from a blue-green glow to a brightly coloured flashing display of multiple colours combined. This light is created by special cells in their bodies called phagocytes, which produce and emit light when triggered by specific chemical reactions. This phenomenon not only adds to the beauty of Jellyfish but also serves as a defensive mechanism, warning predators of their presence and helping them to avoid being attacked a little bit, like how some insects, plants or animals are brightly coloured to warn people.

Jellyfish are found in every ocean on Earth and come in many shapes and sizes. Some species are harmless and small; others can grow several feet in diameter and pack a powerful enough sting to seriously injure or even prove fatal in minutes. Despite lacking complex organs and structures, Jellyfish are incredibly efficient at capturing their prey. They use their tentacles, lined with tiny, stinging cells called nematocysts, to paralyze and catch small fish and plankton. Although Jellyfish are simple creatures, they play an essential role in the ocean ecosystem. They are a food source for many animals, including sea turtles, fish, and even some birds. They also help regulate other species' populations by competing with them for food and space. Studying Jellyfish and their bioluminescence has led to many scientific discoveries and advancements. Scientists have used jellyfish genes to create fluorescent proteins (Fredrick, 2019), which have been used to track cells and proteins in medical research. Jellyfish have also inspired the development of new lighting technologies, such as bioluminescent streetlights, which are energy-efficient and environmentally friendly. If you are interested in reading up on this and the underlying mechanism behind this, here is the link to an article I found which is a great read

In conclusion, Jellyfish may not have a brain, heart, bones, or eyes, but they are incredible creatures that have amazed and captivated humans for centuries. Their ability to produce bioluminescence adds to their mystique and serves as a reminder of the beauty and complexity of nature. By studying and appreciating these unique creatures, we can better understand the ocean ecosystem and the natural world as a whole.

Caller, A., Lundy, A., Meakin, E., Milton, O., Patrick, A., Racadio, M., & Tuckwell-Smith, C. (n.d.). The future of bioluminescent streetlights. University of Nottingham. Retrieved March 14, 2023, from https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/naturalsciences/study-with-us/teaching/synoptic-projects/the-future-of-bioluminescent-streetlights.aspx

Frederic, E. (n.d.). This jellyfish makes glowing proteins previously unknown to science. Science. Retrieved March 14, 2023, from https://www.science.org/content/article/jellyfish-makes-glowing-proteins-previously-unknown-science

1 note

·

View note

Text

Making Sense of Nature-Interpretation

I found this week’s blog post particularly hard to write since I feel that there are so many things about nature that I love and find exciting. What I find inspiring in itself is the interconnectedness of the natural world and how interdependent we and other species are upon one another and the continued cycles and processes underpinning life on this planet. In the end, I settled on the decision to interpret a species that I have discovered since arriving in Canada for my exchange year. This species is the Beluga Whale.

Beluga whales are fascinating cetaceans which are found in the cold-Arctic and sub-Arctic waters of the northern hemisphere (WDC, 2022). They often migrate from the arctic in the fall when sea ice forms, and then return back again in the spring to feed as the ice begins to melt (WWF, 2023). However, some populations have taken up residence in just one area, like the St Lawrence Estuary population in Quebec, where I was lucky enough to see them myself. The first thing you will notice about these whales is their pure white colour and iconic rounded forehead. Beneath their skin, they have a thick layer of blubber which helps to insulate them from the cold arctic waters (O’corry-Crowe, 2009).

youtube

What makes these whale species even more fascinating is how social these animals are and the way that they communicate with one another. They travel with one another in large-sized pods, often changing between different groups on a regular basis (WDC, 2022). Of all other whale species, these are one of the most social and vocal, producing musical sounds including chirps, squeals, whistles and clicks that can be heard above and below water (WWF, 2023). Music is everywhere in nature, and the Beluga whale certainly embodies this:

youtube

Yet, these incredible species confront a number of threats to their survival, which most often can be attributed to the actions of humankind. Indeed, they are hunted for food, but also for entertainment by the so-called marine park industry (WDC, 2022). Since coming to Canada and learning of these animals, I was horrified to find out that belugas are still being kept in marine parks across the US and at Marineland in Canada. This is a huge injustice to the freedom and respect that these animals deserve. These whales are also being threatened by the increased noise pollution induced by marine vessels, which compromises their ability to communicate with one another (WDC, 2022). Climate change is also having a huge impact on wild populations since they depend on the existence of sea ice, which is increasingly being lost under warming temperatures (WWF, 2023). Beluga whales play an essential role in maintaining the health of marine ecosystems, but also have cultural significance to indigenous communities that reside in Arctic areas (Worden et al., 2020). Therefore, their protection and conservation are of huge priority.

My major is in social science, so this knowledge that I have of beluga whales has come about purely from my own encounter with the species and my interest in researching and learning about them for myself. I think this highlights the fact that all of us can become interpreters of nature, no matter our background. I think my role as an interpreter in the future will revolve around reminding individuals of their place in nature and how our existence is tied to the health of our environment and the incredible organisms that we share it with. Thus, how we treat our natural environment, including species like the beluga whale, will and has already had repercussions for both us and a multitude of other organisms and natural processes that exist across the world. The intelligence, beauty and complexity of the beluga whale remind us of the respect and appreciation that these incredible creatures, alongside other organisms on this planet, deserve.

References:

O'corry-Crowe, G. M. (2009). Beluga whale. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-373553-9.00030-4

WDC. (2022). Beluga whale. Whale & Dolphin Conservation UK. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://uk.whales.org/whales-dolphins/species-guide/beluga-whale/

Worden, E., Pearce, T., Gruben, M., Ross, D., Kowana, C., & Loseto, L. (2020). Social-ecological changes and implications for understanding the declining beluga whale (delphinapterus leucas) harvest in Aklavik, Northwest Territories. Arctic Science, 6(3), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2019-0027

WWF. (2023). Beluga. WWF. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/beluga

0 notes

Text

Hi Cidalia,

I really enjoyed reading your post this week and getting an insight into the importance of music in your life. I too feel that music is a constant in my life; I also listen to it every day!

I really like the way you unpack the different interpretations of the presence of nature in music and vice versa. I can see how the music/sounds made by nature, like raindrops and bird songs, can help to give you a sense of calm and relaxation; I can definitely relate to this. Often if I am stressed or struggling to sleep, I will listen to a Spotify playlist like the one you have shared here to help calm myself.

As you say, many music artists use nature within their songs to express emotion. A song called Birds by Imagine Dragons, which I mentioned in my blog post this week, came to my mind after reading your discussion of the fact that nature often serves as a metaphor and symbol within songs to express such emotions and personal stories. The way I interpret this song is that the birds embody how the narrator and someone special they care about are forced to leave one another and journey in different directions.

You also raise an important point about how songs about nature can help spread awareness about the contemporary environmental and social crises that we face in the modern day. I had a look at the website you shared and I found it really interesting to discover some familiar and unfamiliar songs on the list- thank you for sharing this! I agree that music can therefore serve as a significant means of helping individuals to develop and strengthen their connections with nature (Beck et al., 2018). Music can be accessed almost anywhere too, so it also acts as a very accessible means of engaging with the natural world.

I really enjoyed hearing your thoughts, thank you!

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World. Sagamore Venture.

Nature Interpretation through Music

Music is something that is integrated in my everyday life. Honestly, I simply don't know how to go a day without it. Cleaning, doing homework, walking my dog, exercising, driving. I constantly have music playing throughout my day.

When considering music and nature, there are many ways one can interpret this concept. For instance, one can simply listen to sounds made by nature as a form of music. Many forms of music even include recorded sounds from nature. Such as raindrops, thunderstorms, birds chirping, waves clashing, and so much more. A specific example of a form of music is called Biophony, which can be defined as the cumulative sound produced by organisms within a specific biome (Clarke, 2022). Personally, I find sounds from nature to be very calming and help me to relieve feelings of stress and anxiety. Often, when I am struggling to fall asleep or just relax, I play nature white noise sounds (I especially like ones with whale noises, bird noises, and heavy rain).

Others, use references of nature to convey particular feelings and emotions in their music. I would say nature in music helps provide a sensational impact. In fact, many of the greatest sources of inspiration has be drawn from nature and many artists use symbols of nature to express themselves in songs.

Many other songs have been inspired by environmental issues, and have used music as a way to advocate for making a change for the better. The textbook mentions how music can be used to bring awareness to nature and resource issues, which has resulted in many positive outcomes (Beck et al., 2018).

The following link includes some examples (feel free to check them out and add to your playlists! ;) ) :

Either way, combining the beautiful aspects of nature and music can be utilized as such a powerful tool of expression. Music can truly be an enchanting and compelling way in providing others with a deeper understanding of the importance of nature, strengthening their connections with nature (Beck et al., 2018).

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World. Sagamore Venture.

Clarke, N. (2022, August 15). What is biophony? Definition and examples. earth.fm. https://earth.fm/glossary/what-is-biophony-definition-and-examples/

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nature Interpretation Through Music

To me, music is everywhere in nature. I feel a sense of calm and joy whenever I step outside in the morning and hear a bird song; it is beautiful. In the busy lives that we lead, I feel like it is so easy to forget to listen and appreciate these sounds in nature, to stand still when you’re in a park, a forest or any natural space and truly notice and hear the music that’s surrounding you. I was lucky enough last week to visit Banff for the first time last week; here, I visited a Wolfdog sanctuary, where I heard the collective howls of these animals. It was an amazing experience that gave me literal goosebumps. As Gray et al., (2001) highlight, the music created by humans has a strong similarity to that of other species; thus, music likely pre-dates humanity and has prevailed within our surrounding environment long before our existence. Music isn’t just created by the communications of individual organisms like whales and birds, but it can also be heard simply through the movement and rustling of trees in the wind, to the sound of raindrops falling to the ground. This is what I mean when I say that I hear music in every aspect of nature.

Yamnuska Wolfdog Sanctuary, Alberta.

On a personal level, I derive spirituality from and through nature. Part of the way I feel this is through the music of the natural world. As Mallarach et al., (2012) convey, nature can create spiritual and intimate feelings of fascination, humility, awe, deep proximity and continuity among us. I derive a lot of comfort in the sense of continuity that nature provides; this helps me cope with both personal and broader societal challenges that I perceive. Indeed, the threats posed to natural ecosystems in today’s world are immense. Still, when I go for a walk in a natural space, I find comfort in the belief that despite the suffering that may ensue for both our own kind and other species in the present and future as a consequence of this, nature in some form will find a way to prevail. I also feel a sense of awe at the beauty and power of mother nature; it causes me to reflect on my insignificance relative to the wider natural world and I find comfort in this thought. Arguably current western society is inherently underlain by the assumption that we are separate from nature; I believe this is inhibiting many of us from establishing and reflecting on these spiritual and emotional experiences and connections that we have to our natural environment. Therefore, through nature interpretation, it is vital that we encourage learners to reflect on these relationships and deeper, more personal understandings and connections with nature to ensure a more lasting impact.

The music we produce ourselves as humans often reflects the natural world through the lyrics, the sounds utilised, or simply the emotional connection and memories we associate with a song. In one of my previous posts, I shared an artist, The Paper Kites, whose music about nature I really connect with. Another song about nature that I attach significance to is the song Birds by Imagine Dragons. I discovered this song during the UK's COVID-19 spring/summer lockdown. As for many, this was a time when nature became a form of stability and escape from the worry and uncertainty of the pandemic. I would often listen to this song and feel a sense of comfort in the continuity of nature. Another song that reminds me of my experiences of witnessing some of Canada’s natural landscapes since being here, particularly on some of the road trips I have taken in Quebec and Alberta, is Lord Huron's song, Long Lost.

youtube

youtube

As beck et al., (2018) highlight, digital media, including our ability to listen to music through technology, can be a really powerful means of connecting us with our natural surroundings and also reaching wide audiences. Indeed, there can be multiple barriers preventing individuals from being able to have direct, physical interactions with nature, but technology and the media has made it possible for individuals to access nature wherever they are, including their own home. Indeed, when I think of this, the first thing that comes to my mind is the power of television documentaries like Blue Planet in enabling individuals to personally connect with natural organisms and ecosystems that they may never physically be able to witness in person. It can then simultaneously convey important messages and raise awareness concerning the need to protect these environments in the face of global ecological threats induced by individual and collective human behaviour.

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage : for a better world. Sagamore Venture.

Gray, P. M., Krause, B., Atema, J., Payne, R., Krumhansl, C., & Baptista, L. (2001). The Music of Nature and the Nature of Music. Science, 291(5501), 52. https://link-gale-com.subzero.lib.uoguelph.ca/apps/doc/A69270354/AONE?u=guel77241&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=fb9366a8.

Mallarach, Josep-Maria (ed.). Spiritual Values of Protected Areas of Europe: Workshop Proceedings. Bonn, Germany: Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, 2011. 170 pp. ISBN: 978-3-89624-057-6.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hi!

I really enjoyed hearing your thoughts on this week’s topic of nature interpretation through history. It was interesting to learn that your perception of nature interpretation has been broadened through taking this course and it's amazing that this has changed how you plan to approach interpretation in the future. I too now feel like I have a much deeper understanding of how, as interpreters, we can explore nature with our audiences through various lenses.

I agree with what you say about history getting a bad rep sometimes for being dry and boring. From the sounds of it, the UK system (where I received my education) is very similar to how you describe that of Ontario; there was a high emphasis on world wars and political topics. However, like you, I was also lucky enough to have a history teacher who made the subject really engaging and exciting. I agree with you that what we learn in these school settings represents only a fraction of what history learning can incorporate; history is an extremely broad subject that has influenced almost everything that we know and that exists around us today. Your picture of the rock outcrop in Killarney Provincial Park demonstrates this really well and is also mind-blowing to me too!

Finally, I resonate with how you expand upon Hyam’s message; that through reflecting on the past within interpretation programs, this can enable learners to elicit a connection and emotional response to nature. As you say, by exploring the history of an element of nature, this can foster learners to understand and appreciate the significance of its existence and develop a sense of respect and stewardship towards it. Indeed, if we are to collectively tackle some of our biggest global ecological challenges today and into the future, like climate change and biodiversity loss, we must reflect on our history and past actions towards nature and learn from them.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts!

Nature Interpretation & History

As we continue to work through the topics and themes of the course, I’m finding my own understanding of what nature interpretation is and what it looks to be constantly evolving and expanding. At the start, I’m almost embarrassed to say, but I had a very rigid and unoriginal view of what nature interpretation looks like out in the field. It may be due to my own job experiences, but guided hikes, overnight field centre trips, environmental education programs, was the extent of what I associated with the topic. After working through Unit 4’s topic of Nature Interpretation through Art and now this week's topics of Nature Interpretation through History and Writing, I’ve been reflecting on my own practice in the role of nature interpreter and have come to the conclusion that I’ve been greatly lacking in harnessing cross curricular interpreter skills.

Creating effective nature interpreter skills can only be enhanced by understanding and incorporating the methods for planning and learning that are successful in other subjects such as art, writing, and history. From now on, I’m planning on making a conscientious effort to remove myself from viewing my programming strictly from a science based lens when creating new lessons. I often find myself going through waves of “writer's block” after creating what feels like the 100th lesson on an environmental topic, and I’m hoping this new perspective is a breakthrough in offering some new inspiration.

When exploring the topic of the importance of History and how it relates specifically to Nature Interpretation, it almost seems like the perfect fit. As mentioned by Beck et. al (2018), History and interpretation as well as the written word is meant to elicit an emotional response, by allowing the reader to relate their life to a story of the past. I think that History often gets a bad rep as being boring and dry due to the limited exposure with the subject in the intermediate senior years, focusing more on politics, ancient civilizations, and world wars. I actually loved my experiences with History classes thanks to an amazing animated teacher I had in high-school, who did a fantastic job of using methods from the arts to spark an interest and connection between us the students and the time periods we learnt about. He would get on all fours to enact as best he could what trench warfare looked like. Unfortunately, the curriculum for intermediate/senior grades (at least in Ontario) only exposes us to this narrow version of what History learning is, and I believe that for many students who did not get lucky with a passionate history teacher, the interest in History as a topic ended there. But as we know, History is a broad overarching topic that can be applied across all others including music, science, politics, art , food etc, and in order to gain a better understanding of the present state of a topic, any topic, we must understand the whole story.

Rock outcrop in Killarney Provincial Park, where the rocks are between 1-3 billion years old. Geological history, mind blowing (to me).

“There is no peculiar merit in ancient things, but there is merit in integrity, and integrity entails the keeping together of the parts of any whole, and if these parts are scattered throughout time, then the maintenance of integrity entails a knowledge, a memory, of ancient things. …. To think, feel or act as though the past is done with, is equivalent to believing that a railway station through which our train has just passed, only existed for as long as our train was in it.”

(Edward Hyams, Chapter 7, The Gifts of Interpretation)

One of the ways Miriam Webster defines Integrity is “The quality or state of being complete or undivided : synonym - Completeness. I found the quote by Edward Hymans to relate extremely well to a theme I’ve discussed a few times throughout my blog posts: my goal for nature interpretation: inspiring environmental stewardship and ultimately caring for nature. Creating experiences for learners that only allows them to interpret what’s in front of them in the moment, the now, is limiting in the potential for eliciting an emotional response and connection to the program. I believe that taking the strategies of writing and history interpretation, where one uses the past to foster a connection to the present, can only enhance the quality and overall goal of nature interpretation. Rather than observing a 200 year old maple tree for its sheer size and sap production, let’s take ourselves back through time to when that maple seed first helicoptered down to the forest floor. What events has this tree lived through? Was was happening in each of them? After which experience are learners more likely to feel a connection and understanding of the importance of that tree? A completed story is one of integrity. "It is critical to preserve and interpret memories so those memories can inspire action today” (Beck et. al, 2018, p.327).

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage : for a better world. Sagamore Venture.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nature Interpretation Through History

"There is no peculiar merit in ancient things, but there is merit in integrity, and integrity entails the keeping together of the parts of any whole, and if these parts are scattered throughout time, then the maintenance of integrity entails a knowledge, a memory, of ancient things. …. To think, feel or act as though the past is done with, is equivalent to believing that a railway station through which our train has just passed, only existed for as long as our train was in it."

(Edward Hyams, Chapter 7, The Gifts of Interpretation)

There are three parts of Hyams's quote that reach out to me; the first is that the nature of our present reality is a product of the several events and happenings within our history which are ‘scattered throughout time’. Indeed, the remnants of such past events, whether physical or psychological, would be perceived as invaluable if we did not collectively recognise the importance of understanding the past to comprehend our present and future existence. Beck et al., (2018) reinforce the vital role that historical interpreters play in enabling individuals to make connections between educational and enriching narratives of history and their own lives.

This brings me to the second aspect of Hyams's quote that I want to expand upon, that the ‘maintenance of integrity entails a knowledge, a memory, of ancient things’. Beck et al., (2018) highlight the importance of preserving memories and communicating them through interpretation activities, since both positive and more tragic stories of historical occurrences, including human conflict and discrimination, can otherwise become lost over the course of new generations. As interpreters, we must keep these memories alive, for they can shape and alter audiences' perspectives and worldviews and inspire social action within our present day. One ‘place of memory’ (Beck et al., 2018: 327) that I have had the opportunity to visit myself is Anne Frank’s House in Amsterdam. This museum provided an incredibly moving way of experiencing the story of Anne Frank, a German-born Jewish girl who was a victim of the Holocaust. When exploring the house, we were surrounded by videos, photos, quotes from her well-known diary entries and physical items that helped to convey her experiences of hiding from Nazi persecution. I personally found the experience incredibly moving and emotional, and it enabled me to reflect upon the fact that we are still seeing similar acts of discrimination and persecution around the world today. This museum, therefore, serves as a vital means of ensuring Anne’s story and voice continue to be heard by current generations, and that light continues to be shed upon such historic and contemporary human rights issues within human civilisation.

However, arguably the most powerful part of Hyam’s statement is the part where he states ‘To think, feel or act as though the past is done with, is equivalent to believing that a railway station through which our train has just passed, only existed for as long as our train was in it.’. This train metaphor is extremely powerful in demonstrating how our current lives are shaped by the historical journey and experiences of the generations of humans who have come before us. As Beck et al., (2018) write, interpreters are responsible for illuminating these stories; this includes interpreting native and indigenous cultures and their experiences. Not only that, just like a train track, the action and direction we take now will influence and shape our future path. Indeed, the illumination and sharing of the stories of those who experience oppression and hardship by museums and historical sites can become a means of facilitating advocacy, education and civility in the present day (Rose, 2016).

Bringing this back to nature interpretation, history is essential for ensuring a more environmentally sustainable and just future for humankind and this planet. Indeed, global environmental issues such as climate change require us to reflect on our past actions, recognise where we went wrong, and utilise this to envision solutions. A documentary that reinforces the importance of delving into the past in order to understand the lack of progress towards addressing climate change that we see today is ‘Merchants of Doubt’ by Robert Kenner. This documentary explores how inaction on climate change has been fuelled by historical challenges in science communication and the efforts of the fossil fuel industry and various political figures to cast doubt over the scientific consensus on climate change. It then draws comparisons between the global warming controversy and that of the earlier controversy surrounding the tobacco industry and the health effects of smoking. Similar tactics were adopted by sceptics and members of the tobacco and fossil fuel industry; history has repeated itself. The film concludes by highlighting that it took fifty years for science to prevail concerning the dangers of smoking. We are running out of time to address climate change, so we must reflect and learn from these destructive patterns of ignorance and denialism and prioritise action on this climate crisis within our present and future.

Here is the trailer for the film if you would like to take a look:

youtube

You only have to watch the news today to see how the continued degradation of our planet in the past and into our present is currently impacting both human and non-human populations; history must be learnt from to ensure a more sustainable and environmentally just future for us all.

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World. Sagamore Venture.

Rose, J. (2016). Interpreting difficult history at museums and historic sites. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield.

0 notes

Text

Hi Cameron,

I really enjoyed hearing your thoughts concerning the immense challenges surrounding the communication of environmental issues. You pose questions that often come to my mind when I think about my future in environmental education and interpretation; will our efforts even be effective? And like you say, even with all our efforts, what if people aren’t receptive to the things we have to say?

I too share your values and beliefs which you describe, including believing in the good of humanity. Sometimes I find the huge immensity and number of environmentally destructive processes being driven by humankind too overwhelming to comprehend; however, I retain the hope that we will come together as a collective global community in the face of these challenges. In my mind, if we do not have hope, then we have nothing.

The thematic question you pose is an important one which has definitely got me thinking. I agree that communication is a major pitfall that’s fuelling the continued destruction of our natural environment. As you say, the polarization within modern human society is immense; our socio-economic and cultural existence is intertwined with our treatment of nature. In my view, the only way to achieve an equitable understanding of environmental issues and collaborative change amongst the global community is to simultaneously address the underlying socio-economic inequalities that are entrenched within modern society. Indeed, even if communities living in close proximity to the Amazon Rainforest are given access to such information about environmental issues, this understanding will not prevent them from engaging in deforestation activities if they have no other livelihood opportunities that can help to support themselves and their families. If anything, I feel that the responsibility for the ‘blatant disregard for our planet’ that you describe heavily lies with those of us in the West, particularly with concerns to our contribution to climate change. I feel that we have a global responsibility to lead the way with concerns to the treatment of nature, which should involve the transformation of our global socio-economic relationships and activities (including the elimination of the continued legacies of colonialism).

Overall, I do agree that prioritising transparency and freedom of information on a global scale will be essential in allowing us as all to demand wider system change and put a stop to this global destruction of the planet on which we live.

Thank you for raising some great points for discussion!

Why can't we be better? (Unit 05: Freelance)

When I look at this photo I see more than just the lake, or the day it was captured and why I was there. To me this photo represents adversity. The goal is the other shoreline, to get there you have to swim. Without any context, it's a guessing game full of variables; temperature, chemical hazards, wildlife, boaters, depth, distance, time constraints, weather, etc. The importance of this comparison is that I view the challenges of communicating from the highly-educated to the general public and vice versa, the same way. A battle of adversity. Are you willing to make the swim? Is it worth it to even try? Will anyone care?

I believe in the freedom of information, the freedom of speech and the access to clear, capable and conscious communication for all and the effectiveness of a well-informed electorate to make morally and ethically smart choices. I believe in the good of people and our responsibilities as co-habitants of this planet to be environmentalists because we posses the power to do so.

Thematic Question (Please read carefully): Why would you, purposely leave a space worse than how you found it?

I find the context of this question to be applicable on numerous stages of argument in benefit of environmentalism and an advocate of a strong collaborative global society. The thought I am trying to instil in your minds is; what reason do we really have that excuses us for acting deliberately harmful to our planet?

In my opinion, I believe our pitfall lies within our communication. We currently live in one of the most polarizing eras of humanity, from civil rights issues, the protection of biodiversity against medical/technological/economic advancement, population and sustainability crises, to acts of war. The way we conduct, present and express ourselves individually and as part of a group dictate the terms of our situations. Yet, we choose to act in blatant disregard of our planet and the life it is able to provide and sustain. The solution is to provide everyone with the information and process to effect collaborative positive change, because the consequences of inaction from unwillingness and ignorance is morally and ethically destructive.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nature Interpretation Through Science

This week’s readings got me thinking about my own experience of nature interpretation through science. I think one of the key moments when I both became aware and passionate about environmental issues was during my school science class when we touched on the topic of climate change. This global crisis only constituted one page of our textbook at the time and I remember feeling both shocked and overwhelmed by the potential implications of this issue for our planet and society. Yet, when I went home to my family and I mentioned this issue to them, they didn’t actually know what I was talking about. This highlighted to me how our schooling system in England was failing to provide us not only with an understanding of these environmental issues but also failing to empower and equip us with the skills needed to address them within our local and global community.

I have retained this same passion throughout my life and environmental education in school settings actually constituted the topic of my research dissertation last year (back in the UK). As Wals et al., (2014) highlight, it is essential that science education integrates and engages with the concept of sustainability to provide a more interdisciplinary and contextual approach to environmental issues like climate change. Indeed, my degree in geography and international development has allowed me to explore the deep interconnectedness between local contexts and environmental issues; in order to protect nature, we cannot view nature and human society as separate entities. When carrying out my dissertation, I initially came across a really interesting blog that talks specifically about climate change education. It explores how climate change education needs to be transformed in the West, namely to diverge from the assumption that cognitive skills and knowledge will always prompt individuals to take action on such environmental issues (Silova et al., 2018). Instead, it emphasises how the likelihood that individuals mobilise for environmentally beneficial actions is dependent on culture, including their identity and concept of self (Silova et al., 2018). They summarise that:

"For most ‘leading’ educational researchers, both the prevailing worldview and options for climate change response remain trapped in a Western-centric, modern schooling echo chamber: we hear virtually the same ideas presented as contemporary solutions to climate change as the ones put forward in the past as solutions to the puzzle of ‘development’ – i.e., economic growth, catch-up with the Anglo-American-European models, continually rising standards"(Silova et al., 2018, para.12)

Here is the link to the blog if any of you would like to give it a read:

It is also definitely worth recognising that nature interpretation through science also occurs outside of a formal schooling environment. Whilst in Canada, I have had the opportunity to visit the Biosphère Environment Museum in Montreal. The various exhibits and interactive activities here engage people of all ages in discussions relating to environmental science including the threats faced by nature and potential solutions to protect it. Whilst visiting, I was given the chance to participate in a virtual reality experience which gave viewers an interpretation of what the future might look like if we continue polluting our environment with plastics. This highlighted to me how technology can serve as a vital means for communicating environmental science and engaging a wider diversity of learners (visual, auditory etc.). As Merenlender et al., (2016) suggest, technology can also open up really valuable opportunities for individuals to contribute to citizen science initiatives, which can engage a diversity of actors in helping to address socioecological challenges.

Biosphère Environment Museum, Montreal.

A Green Wall in the Biosphère Environment Museum, Montreal.

One of the things that Merenlender et al., (2016) also bring to our attention is the importance of science education that makes connections with the local community and environment of learners. In both formal and informal education settings, linking education to the local level can bring relevance to science and associated disciplines. Approaching environmental issues in this way and presenting stewardship actions that are achievable and grounded in local contexts, can act to empower individuals to address these issues that can otherwise seem too overwhelming to think about sometimes.

References:

Merenlender, A. M., Crall, A. W., Drill, S., Prysby, M., & Ballard, H. (2016). Evaluating Environmental Education, citizen science, and stewardship through naturalist programs. Conservation Biology, 30(6), 1255–1265. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12737

Silova, I., Komatsu, H., & Rappleye, J. (2018, October 12). Facing the climate change catastrophe: Education as solution or cause?. NORRAG BLOG (Network for International Policies and Cooperation in Education and Training). Retrieved February 11, 2023, from https://www.norrag.org/facing-the-climate-change-catastrophe-education-as-solution-or-cause-by-iveta-silova-hikaru-komatsu-and-jeremy-rappleye/

Wals, A. E., Brody, M., Dillon, J., & Stevenson, R. B. (2014). Convergence between science and environmental education. Science, 344(6184), 583–584. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1250515

0 notes

Text

Hi Hailey,

I loved reading your post this week! I agree with you that art can give us the freedom to experience and share nature in a more creative and expressive way than some other forms of interpretation. I’m not from Canada and my knowledge of artwork isn’t amazing, so I had never heard of the group of seven before this weeks unit and your post. I found it really interesting to hear about what you know of Tom Thompson; I really want to visit Algonquin and I can only imagine what beautiful scenery his paintings portray. I resonate with the point you raise, that these paintings enable individuals to seek meaning and connections with nature that are completely subjective to their own interpretation.

I can also relate to the relationship you have with music and how this enables you to connect with nature. I really enjoyed hearing about your memories of sitting around the campfire; I have similar memories of camping back in the UK as a Girl Guide or with my friends and family when a guitar would always be whipped out for a sing-along during the evening. As you say, in these moments all the stresses or thoughts of the day dissipate and you have time to reflect on and appreciate where you are and your natural surroundings.

The photograph you have shared is beautiful; I can definitely see how you also feel the “gift of beauty” (Beck et al., 2018) through your photos. I love the contrast between the bright flames and the snowy landscape; I definitely resonate with your point that this form of art can enable us to reconnect with nature when we reflect and look back on these photographs. I thought I’d share with you a picture I took when I went on a cabin trip last semester; it is a really fond memory for me, as I felt disconnected from the pressures of life here and extremely close to nature. This photo is from inside the cabin at night, where we all sang songs and played group games around the small fire.

Collingwood, Ontario.

I really enjoyed hearing your insight, and I look forward to reading your future posts!

Mia

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T.T., Knudson, D.M (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World. Sagamore Publishing.

I think the use of art is an important tool to use as a nature interpreter. Artwork is a fun and creative way to share environmental experiences and to grow a stronger relationship with nature. Artists have been using painting since 19th century to keep wilderness landscapes protected for future generations (Beck et al. 2018). Paintings can be used as a form of photography to remember the landscape or nature experience that someone wants to hold on to or even as a tool to share with others. Individuals are constantly looking at past artwork and interpreting it, to enhance viewers experiences. When I think of interpreting nature through art, I immediately think of the group of seven. The Group of Seven was a group of Canadians who painted landscapes from 1920 - 1933 (The Group of Seven, 2002). Personally, I have heard a lot about Tom Thompson and his paintings from Algonquin Park. I enjoy learning about Thompsons work from the park as I spend a lot of time in Algonquin, and it is a great way to make a connection to the scenery. Using paintings to visualize nature that exists can be interpreted in so many ways. One person may be able to interpret one of Thom Thompsons paintings completely differently than someone one else viewing it. The audience can make their own interpretation and connections. After reading some of the course textbook, I discovered that nature can be interpreted through art in various ways. For example, paintings are a prime example, but so is theatre, dance, and music (Beck et al. 2018). I do not have a lot of experience with theater or dance; however, I do listen to a lot of music. Regarding interpreting nature through music, I think of listening to songs and singing along to guitar around a campfire. Music allows the audience to connect with their surroundings and explore the natural landscapes around them. One of my favourite ways to interpret nature is to sit around a campfire with my friends. I have spent so many nights around the campfire listening to a friend play guitar. During these moments I have reflected on the lovely landscape and even took a moment to look at the stars. The “gift of beauty” is the principle that interpreters should instil desire in the audience to sense beauty in their surroundings and to encourage preservation (Beck et al. 2018). I feel the gift of beauty through music as well as my photos. I interpret nature through art is through photography. Looking back through my photos I see several pictures I have taken of nature. I have a lot of photos from my cottage and love to reflect on the moments I spent one on one with nature. The “gift of beauty” is the principle that interpreters should instil desire in the audience to sense beauty in their surroundings and to encourage preservation (Beck et al. 2018). I feel the gift of beauty through music as well as my photos.

This is a picture I took last winter at my cottage. I am sitting by a fire most likely listening to music. Now that I am looking back at the photo, I am reflecting on what a good day that was. This is an example of interpreting nature through art. I interpret those photos differently than a lot of you do, however it is a really good way to feel connected with nature.

Beck, L., Cable, T.T., Knudson, D.M (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World. Sagamore Publishing

Canadian landscape painters from 1920 to 1933. The Group of Seven. (2022). Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://thegroupofseven.ca/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nature Interpretation Through Art

Art is a vital lens through which individuals can connect and explore the natural world. As Van Boeclel (2015) highlights, art-based environmental interpretation can ignite a sense of curiosity and wonder among us all; it enables us to develop a self-awareness of our relationships with nature. I feel that this form of interpretation is particularly essential in the busy, modern world in which we live, where having time to self-reflect on our connections with nature is often difficult; the arts can serve as a bridge between nature and human society to help overcome the ‘way we have distanced ourselves from the more-than-human world’ (Van Boeclel, 2015: 801).

Arts-based interpretation can also be really effective in attracting and engaging visitors who aren’t necessarily passionate about nature and can help to stimulate concern amongst these individuals about the various anthropogenic threats to the environment (Beck et al., 2018). It enables individuals to engage and reflect on their own perceptions of “the gift of beauty”; namely, the sense of beauty that they derive from their surrounding environment (Beck et al., 2018: 85).

What we foresee as having “the gift of beauty” (Beck et al., 2018: 85) is specific to our own perceptions as individuals. Personally, I see this in the sun and sky. One of the key ways that I interpret nature through art on a daily basis is through taking photographs of my surroundings; since being in Canada, I have loved capturing sunsets and sunrises both in and outside of Guelph. When I witness the brightness of the sun, the vibrancy of the blue sky, or the warmth of the sunset colours, I feel a sense of happiness and calm. When I look back at these photographs on my phone, I am reminded of this sense of appreciation I feel towards the beauty of this element of nature. And when I sometimes share these images with my friends on social media, I extend this sense of appreciation to them as well.

University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario.

University of Guelph Arboretum, Guelph, Ontario.

This is another way that arts-based interpretation can be so powerful; it can enable us to experience and appreciate nature, even when we aren’t able to physically access it ourselves. As I reflected upon in one of my previous posts, not everyone has easy access to nature. Interpretation, more specifically through an art lens, can help to connect audiences to nature even if their ability to directly access it on a regular basis, for instance when living in a highly urbanised area, is restricted.

Indeed, music, for example, has the power to connect audiences to nature wherever they might be. For me personally, as an auditory learner, music is a really important way that I interpret nature. I listen to music a lot (maybe a little too much sometimes!) and doing so elicits a strong emotional response from me; indeed, songs have the ability to evoke emotion from us, create images in our imagination and embed words, phrases and facts in our memory (Beck et al., 2018). One song that meant a lot to me during my school years and embodies these traits is Michael Jackson's 'Earth Song’. When I was learning of the huge pressures and destruction that we were (and are still) inflicting on our natural environment during my school classes, I felt a sense of anger, and sadness, but also hope. I could connect with this song, its lyrics and the emotions expressed within it; when listening, I felt and still feel my passion for protecting nature ignite. One of my favourite artists, The Paper Kites, has a beautiful EP called 'Woodland'. Specifically, the songs ‘Bloom’, ‘Featherstone’ and ‘Woodland’ from this evoke for me the sense of calm and beauty that I feel when immersed in nature, or more specifically within a forest. I would definitely recommend having a listen if you haven’t heard of them before!

I’m curious to find out if any of you have a few songs that help you connect with nature?

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: for a better world. Sagamore Venture.

Van Boeckel, J. (2015). At the heart of art and earth: an exploration of practices in arts-based environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 21(5), 801-802.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hi Ryan,

I really enjoyed reading your reflections on what the nature of privilege means to you. I think you raise a really important point that some privileges carry more weight than others and how this concept is closely tied to the notion of intersectionality. Indeed, when individuals are not assumed certain privileges, these relative disadvantages can overlap with one another to exacerbate the social injustice they face within society.