Text

Rethinking identity in music

An article by Keith Negus and Patria Román Velázquez (2002) challenges and rethinks the existing emphasis of how music expresses and informs identity, and vice versa. In the essay, they aim to answer the questions:

It has become so automatic for people to label music based on socio-cultural identity markers. An example I often think of is Carly Rae Jepsen, who despite being a straight female, is deemed a gay cultural music icon.

The authors outline two opposing, but equally limiting theories in the discourse on identity in music. The first, the reflection theory, states that people of a certain identity gravitate towards musical experiences which reflect their own identity. This is problematic, because, in the first place, what gives music its identity label? And second, with the reflection theory, the identity of the music and the identity of the people and places associated with that music become entangled.

The second, the constructivist theory, states that their is a flow from social identity to musical expression, such that music constructs identities, rather than having identities inform tastes in music. This is based on the idea that we don’t really know who we are prior to cultural activities, and how it is only through cultural practices that we get to know ourselves as groups and individuals. However, the problem with the constructivist theory is that it is simply a reversal of the reflection theory. This entails that any type of musical sound can construct any type of social identity. In such a case, would it be proper to say that a white woman listening to music labelled “Black” takes on a black identity?

The authors critically remind their readers: The labelling of people is not the same as the creative acts of those people... Music is surely something else besides or other than identities, and identities are something more (or less) than music.

With those statements, I think the authors were able to capture a problem with existing literature on discussing music. Indeed, there is so much focus on identity, such that research has entered into circular arguments which are never really resolved and are not really relevant in the first place. Granted, identity has links to music, but it isn’t the end-all-be-all of things. Negus and Velázquez were bold enough to point out such misassumptions in the existing musicological literature, and to support it with ideas of how music does not simply bring a sense of affiliation, but alienation as well.

For me, given this shedding-of-light done by Negus and Velázquez, I think it’s important to start thinking about how music intersects with the changing sense of self and the changing sense of the collective--how expression is both reflected and constructed, how affiliation and alienation go hand in hand, how fixed and temporary aspects impact that change in the self and the collective, and essentially, what is essential, and what is simply incorporeal. The idea that the construal of the self and of society changes is something that I feel should guide future musicological research into music cultures and their various intersections.

0 notes

Text

The art world of a composition recital

Things one considers “art” are rarely done in isolation; whether we are aware of it or not, the production of what we consider art is a collective effort. Howard Becker discusses “art worlds”--all the people whose activities are necessary to the production of works defined as art.

I was recently part of a graduation composition recital, where the graduating student composed an opera, entitled Pag-ibig sa Gumuhong Palasyo. Naturally, with an opera, several people are involved: composer, librettist, director, performers, instrumentalists, conductor, lights designer, set designer, production manager, stage manager, etc. The dynamics of the several people involved in the production of a new work merits a look at the art world behind such an endeavour. As Becker posits, understanding art worlds is “understanding the complexity of cooperative networks through which art happens.”

Becker outlines several activities in an art world:

1. An idea of what kind of work and its form is conceived.

In the case of the graduation recital, the student’s teacher probably has much more say than the student, regarding what medium or form he or she wants to write. In the composer’s case, the teacher suggested the form, and the composer defined the form’s specific aspects (i.e. A one-act opera, with each scene just leading to the next, producing the idea of one continuous large work.)

Once the form has been agreed-upon, the composer then sets the ideas of the librettist. They dynamic between composer and librettist is straightforward in this case, as the libretto had already been written prior to the project’s conception. In such a case, the work of the composer is straightforward: setting the text based on her musical ideas.

2. The idea is executed via a physical form--seen, heard, held.

The composer writes the score based on how he or she conceives of the music, and disseminates it to the performers who manufacture the necessary sounds to perform the music as written. This is aided by the use of softwares, such as Sibelius, wherein a midi-form of the “idea” is executed via electronic aid.

3. Devising means for execution

Naturally, being that the work conceived is an opera, the means of execution is a staged performance. (The score is not the end-all-be-all of the execution.) Specific means of execution for a staged performance include choreography, movement, staging, blocking, lights designing, set construction, and the like.

4. Manufacturing and distributing necessary materials

This is where marketing and economics come into play in the production of a graduation recital. Being that this is an academic requirement, funding comes almost exclusively from the student having the recital.

5. “Supporting” activities

There are several “supporting” activities in a composition recital, where the main work is an opera. Interestingly, the composer’s role is diminished early on, once the music is finished. Along the way, however, we performers can also give suggestions and make requests for adjustments regarding the melody’s range, text-stresses, interpretative suggestions, and the like.

Once we start getting into stage work, a new set of roles come into play. The director becomes the primary visionary for the overall direction and style of the unfolding work. Aspects such as type of movement (stylized or natural), what period the story is set in, the way more abstract elements (e.g. death, grief, love) are portrayed, and the like comply to the director’s vision for the work. This, of course, is carried out by the performers, and brought to life by the set and lights designer. The stage manager ensures that everything the director wants is noted down, and is recalled by the performers, movers, and other “support” roles. The choreographer designs movements to tie together poignant points in the director’s vision. The assistant director fills in the gaps between the choreography, acting, and the director’s general instructions. The production manager ensures that everything needed is present, and within the primary financial backer’s budget.

It’s interesting how workload and “hierarchy” interact here. The director simply gives the overall vision, but the assistant director and the choreographer provide much of the means for the vision to happen. At the same time, the performers have to make certain requests or amendments to the assistant director’s and choreographer’s instructions in order to accommodate the musical demands (e.g. too much movement while singing, or having to stand up in order to better support a certain note).

6. Audiences’ responding to the artwork

Naturally, being that the work is a graduation recital, the primary audience becomes the panel, as they are required to give a grade for the ensuing work. At the same time, additional responses are expected of the audience, mostly comprised of music majors who are interested in hearing a new opera.

7. Creating and maintaining one’s rationale for all other art activities

Being that the opera was a composition recital, its rationale was very much utilitarian: to produce a work that meets the requirements for a graduating composition recital.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In many ways, a production such as Pag-ibig sa Gumuhong Palasyo exemplifies the nature of an art world. Several conventions are observed in the production, such as the mechanics and hierarchy in a theater-based team, led by the director, and the cooperation and communication between performers and composer, and performers and directing team. Such conventions in the art world of a composition recital make it possible to produce something of that scale, (within the span of only two months!!!!) though at the same time, one is led to think: “What can be done differently?” I guess such is the plight of the ever-evolving artist, but it’s nice to realize that the artist is never really alone in his or her endeavours.

0 notes

Text

Reclaiming OPM

CHED-Salikha-EPAPC's documentary, Sa Madaling Salita, OPM: Himig Pilipino ng Dekadang Sitenta traces the origins and the journey of original Filipino music during the 1970s.

The Philippines during the 70s was what my mom calls the “peace, make love” era in her childhood, something that certainly reflected US influence among Filipinos back then. As such, music was also heavily inspired by American ideals. US settlements in the Philippines led to xenocentrism among Filipinos, as well as the phenomenon of transculturation, especially in music. In cases when Filipino artists were making waves in the music scene, they were often called the [insert American artist’s name here] of the Philippines.

Eventually, of course, original music by homegrown Filipino bands and artists grew in popularity as well, aided by recording labels, such as VICOR, called a hit-making OPM factory. Indeed, one can credit the rise of OPM to recording labels as much as to the bands and artists who composed and performed them. The role of recording companies was such that the very sound of what was called OPM was solidified, and at the same time commodified. Recording companies copied whatever sound competing recording companies were releasing. If Company A released a dance tune, Company B would also release a dance tune, and so on. So many factors are in play when it comes to labelling something mainstream, but at the time, being mainstream was a must in order to survive the industry. (It’s interesting to see how the evolution of the OPM sound is still heavily influenced by market value and commodity.)

Watching the documentary, I realized that, as much as artistry comes into play when it comes to defining a genre and solidifying a music scene’s sound, somehow, one can never take away the impact and power of marketing and consumerism. Granted, during the 70s, indie artists and groups already existed, but OPM wouldn’t be the way we know it today if music did not become an industry in itself. One is led to think, is independence in the music scene possible at all? But maybe such an interdependence is what allowed us to reclaim OPM from American sound and ideals.

0 notes

Text

Sounds and Poetry of the Streets: Philippine expressive popular cultures

Last week, from September 4-6, Ethnographies of Philippine Auditory Popular Cultures (EPAPC) organized a three-day conference, entitled, Sounds and Poetry of the Streets: Philippine Expressive Popular Cultures. The conference aims to “investigate and celebrate the performative and sensorial aspects of everyday practices and experiences and the transformative ways of contemplating and apprehending them.” (From the EPAPC event page) The conference highlighted keynote speakers, as well as panel presentations of papers exploring different aspects of popular music, from orchestration of hits from the 70s, to protest music, to Sarah G as an artist, and even to why Filipinos go crazy for Britney Spears. It was an overall interesting mix of perspectives towards popular music in the Philippines.

I was able to attend the first panel last September 4. The first panel included the following paper presentations:

1. Eddie Peregrina, Keempee de Leon and Japanese popular songs: globalization and transcultural consumption in Philippine popular music (Hiroko Nagai, Ph.D., Ateneo de Manila University)

‘Nakakaiyak, ang ganda’: Aesthetic experiences, values, and responses of Filipino audiences towards popular music on social media (Lea Marie F. Diño, University of the Philippines, Diliman)

‘We’re not that innocent’: The democratized fantasy of Britney Spears to Filipino, Catholic, millenial imaginations (Deirdre Patricia Z. Camba, University of the Philippines, Diliman)

Arrangers of 1970s OPM: A musical analysis in the historical context of Pinoy Pop Orchestration (Cristina Maria P. Cayaybyab, University of the Philippines, Diliman)

As a psychology graduate, of interest to me were the presentations by Lea Marie Diño and Deirdre Patricia Camba, especially since they dealt with internalized and mental aspects of people’s behaviors and conceptions towards music.

Diño found that, basically, Filipinos’ aesthetic valuations of popular music hinged on three aspects: (1) empathy - How relatable the song is to the listener, (2) emotion - How the song is able to evoke certain emotions in the listener, and (3) memory - How the song is able to bring to mind certain personal memories which may relate to it. Such aesthetic valuations point to a larger picture: the Filipino popular musical experience. Diño concludes her talk, saying that the Filipino popular musical experience is largely affect-based. Filipinos listen to songs that move them, relate to them and their experiences.

As a musician though, one is led to think: Is the actual music (and the technical aspects of the song, such as vocals, arrangement, recording quality), then, much less significant compared to the poetry or lyrics that it sets? Maybe such a consideration can serve as a follow-up study to Diño’s findings.

Much of the YouTube comments she presented as sample data for her analysis expressed more affective sentiments on songs that were liked, and more detached and non-affective sentiments on the songs that were not so liked (e.g. “The original version was better.”) Maybe it would be of interest as well to look at the other side of the coin: What makes a song disliked by the Filipino listener? And how do Filipino listeners quantify and qualify value judgments towards songs that are not as liked, or are outright disliked?

The next presentation, by Camba, focused on an artist dear to my heart and central to my childhood: “Our Lord and Savior, Britney Spears” (Camba, 2019)

It was interesting to see how Camba fleshed out several of the ways Britney Spears continues to exert her influence in Filipino listeners through various fan practices (participation, collectives, blogging and fanzines, fan videos, cosplay, concept cafes, and the like). Admittedly, the extent of my being a Britney-fan goes only to me knowing the lyrics of all her songs from the 90s; I haven’t watched a Britney concert, cosplayed as Britney, nor written a fanzine or blog about her. It’s interesting to see, though, that there remains a fascination for Britney up to today’s Filipino listeners.

Much of Camba’s presentation focused on a pivotal moment in Britney’s life: the shaving of all her hair following a mental breakdown. Camba posits that this event showed that Britney was not merely a celebrity, she was also a spectator and a participant in the celebrity world and its consequences. Truth be told, when I heard of Britney’s comeback with her new single Piece of Me in 2013, I thought to myself, “Kung kinaya ni Britney mabuhay at bumangon, kaya ko rin.”

What was lacking for me though, was how the fascination for Britney Spears related to the audience qualifiers in Camba’s talk title: Filipino, Catholic, millenial. What characteristics of Filipinos make one gravitate towards Britney Spears? How does the Filipino Catholic identity and culture conflict with, or even reinforce the Britney fascination? How has exposure to Britney influenced the millenial mindset and such?

Either way, though, there is no doubting the influence of Britney Spears amongst Filipinos in my generation. I guess a Britney-phase is inevitable.

It’s interesting to see how varied the topics on popular music in the Philippines range from. Truly, it’s a continuously evolving realm of study, with a huge and maybe even unlimited potential for academic and non-academic discourse (moreso with the increasing use of social media and online platforms). I look forward to the next EPAPC series of talks and presentations!

0 notes

Text

Music culture in focus: Dawani Women’s Choir

I have been part of the Dawani Women’s Choir since 2016, a few months before entering the UP College of Music. Its been quite a ride since then, having joined the group in its re-birth phases, and now being right in the middle of big season plans. Prior to joining Dawani, I was always curious about how all-female choirs work, being that my choral experiences have always been in mixed-voice choirs, and my musical palette with regards to choral singing always involved booming basses and widely-spaced chords. (The constant nagging thought was how would you achieve a “full” choral sound without men? Men again. The answer I got involved a change in my perspective on what a “full” choral sound meant--an expansion of horizons of sorts.)

In looking into the music culture of the Dawani Women’s Choir, I’ll veer to the music-culture performance model, being that we are primarily a performing group. I’ll touch two of Dawani’s projects since the time I joined the group: our first concert following Dawani’s “rebirth,” and the first concert for our latest season.

beauty & light

A fundraising concert for the benefit of the Purple Centers Foundation, together with the UP Cherubim and Seraphim

On affect

True to the title, this fund-raising concert’s aim (well, apart from the aim of fund-raising) was to shed bits of beauty and light into different things, big and small, such as an afternoon on a hill, a mother’s lullaby, a lover’s careful serenade, and even music itself. With Dawani, I have observed how careful programming and piece selection has the goal of producing a cohesive message, in order to maximize the music’s affective capabilities. Indeed, even as a performer, with just the first few chords of Afternoon on a Hill (our opening piece for the concert), was enough to transport me to a place far removed from the usual hustle and bustle that we know of.

<iframe src="https://www.facebook.com/plugins/video.php?href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fliya.dioquino%2Fvideos%2F10154508775393435%2F&show_text=0&width=560" width="560" height="315" style="border:none;overflow:hidden" scrolling="no" frameborder="0" allowTransparency="true" allowFullScreen="true"></iframe>

On performance

Being that beauty & light was a formal concert, this was a relative departure from one’s usual Friday night activity. It was also a ticketed event, with our audience explicitly expecting a formal performance. It follows thus, that certain parameters of formal performances apply, such as reserving applause for the end of each song, refraining from talking or making unnecessary noise, observing proper seating (e.g. Not sitting on the bench reserved for sponsors/VIPs), and the like.

With regards to performance procedures for the performers themselves, we stick to the usual dynamic of following our conductor, and remembering to do all the interpretative and dynamic notes we’ve agreed on during rehearsals. There are not much restrictions regarding movement (i.e. We can naturally move with the music), and much of the performance procedures we adhere to (both consciously and unconsciously) are often to achieve a unified sound. Naturally, there are some aspects which no longer need to be said or defined in the performance context for the performers, such as singing in the same key, starting phrases at the same time, and the like.

On community

beauty & light was a joint concert with the UP Cherubim and Seraphim (UPIS’ children’s choir). Thus, it followed that the central community surrounding the concert comprised of people involved in the UP Diliman community, such as parents and friends of the UP Cherubim and Seraphim members, and friends from the UP College of Music (since at that time, majority of Dawani members were from the UP CMu). The concert was also held at the Church of the Risen Lord, which was within the UP Diliman campus grounds.

In terms of the community within Dawani itself, the organization is quite straightforward, and not as different from other choral groups in the Philippines. We have a principal conductor, Dr. Beverly Shangkuan-Cheng, who serves as our artistic director as well. A music committee helps our principal conductor in carrying out other musical demands in the group, such as helping with vocalization, note-learning, and the like. An executive committee performs administrative and logistical tasks for the group, such as reserving venues, fund-raising, managing members, and the like.

As a member, working on beauty & light (which was also my first concert as part of Dawani) has greatly expanded my views and sentiments towards a choir, beyond it being just a musical group. On an extremely personal note, Dawani has become a musical home for me, even before I formally entered into the world of music and professional singing.

(Somehow, this sense of community that one finds in Dawani has even served as a jumping point for our latest season and our upcoming projects. Please follow our page to learn more.)

On memory and history

On a group level for Dawani, beauty & light served as a catalyst or starting point for: (1) the kind of sound that Dawani can be known for, (2) the kind of programming that Dawani can achieve, and (3) the outside reach (in terms of audience following) that Dawani can tap into. Indeed, following this concert (but still with a lot of hiccups along the way), we boosted our social media presence, levelled up our publication materials, and became more aggressive and intentional in our rehearsals and our project planning sessions.

Three years since beauty & light, Dawani now embarks on its latest season entitled Mosaic.

Mosaic

Dawani envisions this latest season as a musical exploration of shared human experiences, connecting people of different backgrounds, classes, cultures, and even countries. At its core, Mosaic can be seen as a journey towards finding oneself, finding one’s place, and coming together to create a grand work of art.

The first phase of our season, entitled Fragments, explores definitions of home that we have gathered among members of Dawani.

In our programming, we essentially ask ourselves: Where is the road I can call my own? following Stephen Paulus’ The Road Home. The search for one’s place is something I believe to be universal. Somehow, we are all searching for a place in something bigger than ourselves, a place we can call home. It is this aspect of one’s affective nature that Fragments aims to tap into, and to offer answers to as well.

In our music, we explored how home can be found even in the context of feeling lost at first, in the things immediately around us (such as in nature, in the seasons, in change), in our immediate communities, and in our memories. This comes with the realization that where we belong and what we can call home, isn’t just something we have to find out within ourselves, and that the journey of putting together parts of one’s self doesn’t have to be in isolation, as we find ourselves alongside our journey of finding others too.

It is with this idea that somehow, I’ve observed certain community and organization aspects have changed within the group, especially during the performance. I remember Dr. Shangkuan-Cheng telling us that now, performing shouldn’t be with an “I should follow the conductor” type of dynamic, rather, it should be as if we were moving, breathing, and communicating as one, together with the conductor and with each other, rather than in isolation or with a power-dynamic in mind. In order to communicate a sense of community and belongingness, our choir should, first, become such a community--doing away with the power dynamics of conductor-singers, and just simply being and making music as one.

0 notes

Text

Performing Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven

For class, we were required to perform and discuss works by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. My group, consisting of myself, Carlos Serafica, Maria Angelica Uson, Paul Anthony Evangelista, Jon Roi Mediones, and Ma. Reynabelle Jordan decided to perform the following:

Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto in Eb Major, Hob.: VIIe/1 (1st movement)

Mozart’s Piano Sonata in C Minor, K. 457 (1st movement)

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor (Discussion)

Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 in C# minor, Op. 131

It’s quite an eclectic set, considering our group was made up of different instrumentalists (singer, pianist, violist, trumpeter, saxophonist, and Asian music specialist), but we somehow managed.

Jon Roi and I performed Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto in Eb Major, with Jon Roi on the trumpet and myself on the piano. It was quite an easy piece to gel together. The themes are distinct and are passed from trumpet to piano and vice versa. It’s interesting how Haydn valued the sound of the trumpet, and was certainly able to write a piece that was very idiomatic for the instrument.

Next, Carlos played the first movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata in C Minor, with Angelica discussing it. Mozart’s piano sonata is quite unique, in that Mozart rarely wrote in the minor key. The sonata was somehow Mozart’s way of expressing grief somehow, being that he wrote it after the death of his mother.

We could not fully perform Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, however, I delivered a brief report on it. Below are my slides, accompanied by a recording of Bernstein conducting the monumental symphony.

Lastly, we performed an excerpt from the first movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 in C# Minor, Op. 131, except with violin, viola, trumpet, and alto saxophone, since, as I mentioned, our group was an eclectic one. Somehow, the players were still able to express the tone and dynamics Beethoven had written, making the 19 bars played almost as haunting as an actual string quartet. Indeed, Beethoven’s second to the last string quartet is one of the most beautiful pieces of music written. It evokes a prayer, a foreshadowing, and is seamless in its construction, in spite of having seven movements, with different characters in each one.

Preparing for, and performing the pieces mentioned was difficult, but rewarding. It’s amazing how composers in the past still evoke emotion, beauty, pleasantness, and the sublime in today’s listener’s and performers.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bach’s Cantatas: An overview

Sharing our report on Johann Sebastian Bach and his cantatas.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Defining tonality

Let’s go back in time by a few centuries, before proceeding to what would often be labelled as “the weird stuff” (aka a departure from tonality as we know it). Before composers started doing everything they could to stretch the limits of tonality, one composer in the 1700s initiated a revolution in music theory that would result in the rules of tonality as we know it today.

Jean Philippe Rameau rose to prominence late in his life, but his works have influenced composes in the next centuries. He was known as the “Isaac Newton of Music” after writing the Traité de l’harmonie réduite à ses principes naturels (Treatise on Harmony reduced to its natural principles), wherein he used scientific principles to illuminate the structures and principles in music.

Rameau was heavily influenced by Descartes, and this influence is seen in how he attempted to ground the practice of harmony according to the laws of acoustics. Here are the major points in Rameau’s Traité de l’harmonie:

Fundamental to Rameau was the triad and seventh chords as the principal elements of music, from which he would derive the natural consonances (perfect fifth, major third, minor third).

Each chord has a fundamental tone, equivalent to what we know today as the root (lowest note, when a chord is in the root position, or arranged as a series of thirds). Thus, in a series of chords, the succession of fundamental tones would be known as the fundamental bass. The fundamental bass gives a chord its identity, no matter what inversion is used. Thus, the harmonic sequence of a passage is not identified by the lowest sounding note, but by the fundamental bass.

Inversions of the C major chord.

Music is driven forward by dissonance, and comes to a rest or resolves to a consonance. Seventh chords provided dissonance, while triads provided consonance.

A G7 chord (2nd chord in the excerpt) resolving to a C major chord.

The tonic I (main note and chord in a key), the dominant V (note and chord a fifth above the tonic), and the subdominant IV (note and chord a fifth below the tonic) were the pillars of functional tonality.

A IV-V-I progression in the key of C Major

The fundamental bass gives coherence and direction to any piece of music. It also helps in defining the key (tonal center) of the music.

To any musician today, Rameau’s points in his Traité de l’harmonie seems quite commonplace. However, it proved revolutionary during his time, because Rameau constructed a unified system based on universal laws of nature. Thus, for the blessing of functional harmony and tonality, we have Jean Philippe Rameau to be thankful for.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A love affair with the viola

Ralph Vaughan Williams composed a Suite for Viola and Small Orchestra in 1934. Indeed, Vaughan Williams was fond of the sound of the viola, and he wrote the suite for Lionel Tertis, whose talent inspired Vaughan Williams to write the piece.

The suite is comprised of eight short pieces. In class, Paul Anthony Evangelista and I played the second movement, Carol, with a piano reduction as accompaniment.

youtube

Vaughan Williams’ Suite for Viola and Orchestra, with Frederick Riddle as the soloist. Carol is on 3:13 - 5:54.

The main melody of Carol is often played alternately by the soloist and the accompanying orchestra. Much like Vaughan Williams’ other works, it seems inspired by English folk tunes. Indeed, his main melody in Carol is long-breathed, and his harmonic writing does not necessarily follow the rules of functional harmony, following the more modal orientations in English folk songs and in English Tudor music, from which Vaughan Williams adapted his compositional language.

Evident in the score are a variety of meter changes. Somehow, even though the melody is wordless, Vaughan Williams seems to follow a pattern of text in his melodic setting. His lyricism is highly reflected in Carol.

Performing the piece proved quite challenging, indeed. Carrying out Vaughan WIlliam’s flowing melodies, while still keeping in time despite the many meter changes is an often-encountered struggle in performing any Vaughan Williams piece. However, the resulting sounds are, indeed, rewarding and uplifting.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ravel and the Orient

A fascination for the exotic and the orient has often pervaded music in France, as exemplified by works such as Saint-Saën’s Samson et Dalila, Bizet’s Carmen, and Debussy’s Javanese gamelan inspired works. Maurice Ravel was no exception to that fascination.

In 1903, Ravel composed a cycle of three songs for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, entitled Shéhérazade, based on the exotic texts of French poet Tristal Klingsor. (In 1898, Ravel had already composed the Ouverture de Shéhérazade.) In literature, Sheherazade is the heroine and narrator of The Arabian Nights (or One Thousand and One Nights)--a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales, which include tales on history, love stories, various forms of erotica, comedies, poems, and so on.

Shéhérazade is composed of three songs:

Asie (Asia) - The first and longest. “A panorama of oriental fantasy evoking Arabia, India, and, at a dramatic climax, China.” (Rae, 2015) The poet repeats the words “je voudrais voir...” (I should like to see...), as he dreams of escaping his European life to encounter Asian exoticism.

La flûte enchantée (The Enchanted Flute) - A play on sadness and joy, as a young slave girl hears her lover playing the flute outside, while she is tending to her master. To the girl, the music she hears seems like a kiss on the cheek.

L’indifférent (The Heedless One) - A poem filled with incredible longing, about the attraction to the unattainable. Ravel’s setting of this is often regarded as the most beautiful of all of Ravel’s songs; a movement shrouded in sexual obscurity.

youtube

Christiane Karge sings Ravel’s Shéhérazade, under the baton of Stanislaw Skrowaczewski.

In general, all the movements are tranquil and reflective, as heard in the opening and closing segments which are all in piano. Ravel uses the orchestra and experiments with harmonies and textures to evoke an image of exoticism. The cycle is so arranged, such that it opens with “rich, voluptuous tones and harmonies, which evolve to gentle lyricism, and conclude in languid sensuousness.” (Rae, 2015)

Let’s take a closer look at the third song, L’indifférent (15:59), and examine how Ravel paints longing and unattainable desire.

Text and English translation of L’indifférent

L’indifférent opens with a slow, oscillating strings motif in 6/8, on which a flute gently perches atop in 2/4, in the key of E major, starting of with a ninth.

The vocal line follows suit, and enters unassumingly. Ravel demands a fine, French legato on the singer, who sings mostly stepwise atop the oscillating strings motif.

Everything seems still and quiet, until the end of the line “De ton beau visage de duvet ombragé” (Of your fine features, with shadowed down...”), where Ravel surprises the listener with a C# Major 7 chord with a 9th on the vocal line, as a harp strikes, alongside a tenuto on the strings. After this, Ravel somehow “surrenders” musically to the seduction of the beautiful face in the shadows, by returning to his oscillating strings motif.

C#M9 chord on the downbeat of the first measure shown. As if a sigh emanates from the being of one who is so taken by another’s seductive beauty.

As the poet muses further, Ravel leaves behind his oscillating strings motif in place of forward-driving octaves on the strings, and winds providing a counter-melody to the vocal line. Somehow, this reflects the poet’s mind as he continues to fantasize about the beautiful stranger he encountered.

Strings take on the octaves in the left hand part of the piano reduction, while upper winds take on the right hand line. Notice how Ravel repeats his harmonic motif over two measures. This somehow puts the listener and the singer in the realm of fantasy.

Also note how Ravel juxtaposes the D-A on the base with the stepwise motion in the upper lines. Such a compositional technique is known as pandiatonicism, wherein the diatonic scale (as opposed to the chromatic scale) is used without the limitations of functional tonality. (i.e. Without the dissonances having to resolve.)

When the poet bids the beautiful stranger, “Entre! Et que mon vin te réconforte...” (Enter! And let my wine comfort you...), the orchestra comes to a quiet stillness, as if mimicking the poet’s anguish, anticipation, and desperation for the stranger to come and be with him. Again, Ravel uses a 9th to evoke such a mood, and then proceeds to write a descending chromatic line leading up to whatever comes next.

But alas, the poet is rejected. The stranger simply passes by and goes on her own way. Ravel paints this with a quasi-recitative portion, as the orchestra comes to a halt and leaves the voice (the poet) to languish on his own.

Ravel returns to his extended C#M chord as the poet watches in defeat as the stranger walks away. He is left with only the sight of the stranger’s hips gently swaying--frustratingly erotic in every sense.

And to conclude the piece, Ravel returns to his oscillating strings motif, ending with pandiatonically extended triad with a major ninth.

Ravel’s Shéhérazade is, indeed, a masterful painting of the exotic. Ravel achieves this with the use of pandiatonicism, and the use of false modalities throughout the piece (in L’indiffêrent, we only clearly hear the E major tonality in the start and end of the piece). Shéhérazade is, indeed, a prime example of how Ravel influenced the tides in terms of compositional language, orchestral texture, and harmonic colors.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Love and Wagner: Tristan und Isolde

In thinking about Richard Wagner as a composer, one can consider his philosophy on art and music, his perfectionism, the extent to which he would attain such preferences for perfectionism, how he pushed tonality to its limits, and so on. Indeed, Wagner is a giant in terms of the development of a new musical language that would later on influence later composers such as Schoenberg, Berg, and Weber. However, on top of that, in talking about such a giant as Richard Wagner, one cannot ignore that he is, indeed, a man of passion.

Such passion is ultimately illustrated in Wagner’s monumental work: Tristan und Isolde. Gustav Kobbé, author of The Complete Opera Book, introduces the section on Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde:

All who have made a study of opera, and do not regard it merely as a form of amusement, are agreed that the score of Tristan und Isolde is the greatest setting of a love-story for the lyric stage. It is a tale of tragic passion, culminating in death, unfolded in the surge and palpitation of immortal music.

One can surmise that the opera may have been autobiographical. While writing it, it was said that Wagner had been carrying out an affair with Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of Wagner’s friend and benefactor. (Wagner would set Wesendonck’s poems to music--later published as a cycle known as the Wesendoncklieder. Two movements in the cycle were studies for Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde.) It may be that Wagner envisioned himself as Tristan, and Mathilde as Isolde, although by the time the opera was finished, their affair had ended. However, their passion and suffering is preserved in Wagner’s monumental work.

A highlight of Tristan und Isolde is the love duet in Act II--one of the longest (almost half an hour long), most passionate, most opulent duets in the opera literature--O sink hernieder...Nacht der Liebe.

youtube

Ludwig Suthaus and Kirsten Flagstad essay the roles of Tristan and Isolde respectively, under the baton of Wilhelm Furtwängler, with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

Musicologists have cited Tristan und Isolde as a landmark in Western music. Indeed, Wagner went beyond what was conventional in music of his time, with extended orchestral ranges, unexpected harmonies, and extensive use of harmonic suspensions, leaving listeners expecting more and more, and building more and more tension. All those features can be found in the love duet mentioned above.

Almost all 30 minutes of the love duet is a build-up of tension. Wagner employs heave use of secondary seventh chords, which somehow never resolve, or resolve unexpectedly, along with harmonic suspensions. (Such harmonic suspensions are evident in Traüme of his Wesendocklieder, which was a sketch/study of the love duet.)

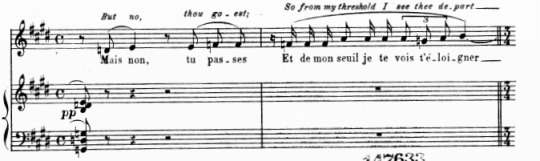

An example of Wagner’s use of harmonic suspension. Observe the tied dotted half notes in the upper voice of the accompaniment. The sound somehow indicates love and longing.

The initial 2 minutes and 40 seconds of the love duet is a giant build-up in itself, which ultimately “resolves” or leads to another more grand harmonic suspension. (0:00-2:39) To achieve this, Wagner uses a combination of chains of secondary leading tone chords, chromaticism in both vocal and instrumental lines, as well as unexpected turns in harmony.

Notice the chromatic vocal lines, as well as the persistently tension-building harmony (Db minor - F fully diminished 7 - G diminished - Fb major 7 - Ab major - Fb major - F minor 7 - F diminished)

The grand harmonic suspension Wagner builds up to.

Wagner’s use of continuous tension paints the struggle of Tristan and Isolde’s forbidden love, as well as the sexual and physical tension brought about by their romance.

Alongside that, Wagner also employs certain motifs to further paint the scene through the music. The love duet is interjected by a reminder from Brangäne, as she keeps watch and reminds the lovers, “Ah, beware! Soon the night will pass.” Brangäne’s watchsong essentially carries the daylight motif. (5:58 - 9:25) (Tristan and Isolde can only meet at night--their fantasy land. Daylight is a reminder of the reality that they must face. This makes the love duet essentially a clash between night and day as well.)

Excerpt of Brangäne’s watchsong, featuring the daylight motif in the vocal line. The harmonic suspensions are still present, but this time, the melodic line seems to go along with it, rather than against it. It’s rather curious that Brangäne’s watchsong--a song of warning and foreboding--sounds eerily more peaceful than Tristan and Isolde’s declarations of love and longing.

The daylight motif is first introduced in the orchestral section prior to the love duet: A falling fourth or fifth ascending in steps.

The ending of the love duet proves surprising and significant as well. It illustrates Wagner’s penchant for the unexpected.

Wagner once again composes a long, slow build-up, this time with the added use of persistent triplets in the vocal and instrumental lines, alongside constantly moving chords, when suddenly it “resolves” to....

...a great, deafening dissonance.

Indeed, Wagner evokes passion evidently in his music, and he certainly knows how to keep listeners on their toes. We see the resolution of Wagner’s monumental build-up only in the final Liebestod (Love Death), during which the cadence coincides with Isolde’s death in the finale of Act 3.

Love and Wagner. What a concept--grand, tragic, and other-worldly.

0 notes

Text

Italian Romantic Opera

During the Romantic period in music, Italian opera was still in vogue. Indeed, Italian Romantic opera ushered in a new formal style of singing--the bel canto style (literally translating to “beautiful singing”).

Gioachino Rossini

This was especially preferred by Gioachino Rossini, whose operas highlighted the voice as the most important element. Rossini demanded of his singers: effortless technique, beautiful tone across a singer’s entire range, agility, flexibility, and control of every type of melody. With the voice in mind, Rossini’s arias typically show tuneful melodies, clear phrases, coloratura, coupled with spare orchestration intending to support the singer. A trademark of his was also the Rossini crescendo, in which Rossini builds up the excitement by repeating a phrase louder each time, often at a higher pitch.

Such musical characteristics of Rossini can be exemplified in the aria, Nacqui all'affanno... Non più mesta--the closing aria of Angelina in Rossini’s La Cenerentola (Cinderella).

youtube

Fredericka von Stade sings the role of Angelina in Rossini’s “La Cenerentola”

The role of Angelina was intended for a contralto or mezzo-soprano. Upon first hearing the aria, one can clearly discern the intense vocal demand placed upon the singer. The range goes from G3, up to a high Bb5, and is highly unforgiving in terms of highly ornamented runs, and long melodic phrases. However, once sung by a master of the bel canto technique, the aria proves incredibly charming.

Alongside the rise of the bel canto technique, Rossini and his librettists also developed a scene structure that distributed the elements of the plot more clearly. In Rossini’s solo arias, for example, the scene structure typically goes as follows:

1. Orchestral introduction (0:00 - 0:33)

Orchestral introduction in Andante. Notice the use of simple accompaniment in the bass line, consisting of repeated block chords. Also note the very flowing, tonal, melodic line.

2. Scena - Recitative section (0:35 - 2:15)

The beginning of Rossini’s recitative section. Here, Rossini uses spare accompaniment to highlight the “spoken” quality of the recitative. Rossini uses florid ornaments to paint important words and to highlight text-stresses.

3. Slow and lyrical cantabile (2:16 - 3:03)

Rossini’s cantabile. Although the section is marked allegro, the singer takes a leisurely pace. In the aria, the cantabile section is brief, immediately transitioning to the tempo di mezzo. In this section, Angelina comforts her sisters and father by offering her forgiveness in spite of how they have shown spite towards her.

4. Tempo di mezzo - Middle section, usually a transition or interruption by other characters wherein something happens to alter the main character’s mood or reaction (3:03 - 3:56)

Here the chorus enters. Notice the change in the accompaniment--it becomes more active and punctuating. This marks the transition to the main aria--Non più mesta.

5. Patter song - Comic portion (3:57 - 5:12)

Notice the light and gentle accompaniment, as well as the highly punctuated vocal and less ornamented vocal line.

6. Lively and brilliant cabaletta to express more active feelings (5:12 - End)

At the start of the cabaletta, both vocal line and accompaniment become more active and persistent.

The Rossini crescendo is, of course, featured in this ending aria (6:06 - 6:45), where Rossini writes in repeated words for the chorus and for Angelina, with stronger accompaniment parts after each segment.

Vincenzo Bellini

Where Rossini was a master of energetic, forward-moving movements, Bellini was a master of long, sweeping, intensely emotional melodies. Indeed, Bellini manages to maintain the purity of his vocal lines, while tastefully and strategically embellishing them in the most dramatic parts. In the simplest way, Bellini’s melodies just flow beautifully, and such power of his can be best illustrated in probably his most famous aria: Norma’s Casta Diva.

youtube

Sonya Yoncheva sings Norma’s iconic aria--Casta Diva.

The aria is Norma’s prayer to the Chaste Goddess (Casta Diva), where she leads her people in a serene prayer for peace. Indeed, Bellini starts the aria with gentle arpeggios, as if setting the mood for solemn, serene, sincere prayer.

Strings take on the gentle arpeggio figurations, while a flute introduces Norma’s initial melody.

Following the haunting orchestral introduction, the aria can be divided into three parts:

1. The main melody, sung solo by Norma (1:17 - 2:56)

Notice how Norma’s melody rests atop the gentle eighth note arpeggio figures in the accompaniment, but seems to never fall on the eighth-note beats. Bellini uses unequal note values extensively in the vocal line (long-short) to better emphasize the text.

A section of Bellini’s main melody. Notice the sensitive text-setting, as well as the tasteful embellishments, and incredibly long-breathed melody.

2. The choir, forming a quite chorus, above which Norma sings a highly ornamented line in her high register (2:57 - 3:59)

A segment of Norma’s highly ornamented vocal line, soaring above the gentle chorus. One would think of Norma’s vocal line as a wordless prayer.

3. The reprise of the main melody, set to new text, alongside syllabic punctuations by the choir. (4:03 - End)

Such is the magic of Bellini’s melodies. Indeed, Verdi would say in praise of Bellini and his melodies: “...long, long, long melodies; melodies such as no one had written before him.” And such a gift is exemplified in Norma’s Casta Diva.

Gaetano Donizetti

Wrapping up the discussion on the Italian bel canto opera tradition, we have Gaetano Donizetti. He, alongside Rossini and Bellini, would later on influence Italian opera traditions, with Verdi and Puccini.

As a composer, Donizetti proved very sensitive to the character’s personality and emotions, and would write melodies that would perfectly capture the character’s feelings, and the scene itself. A writer of both comic and serious operas, he would seamlessly weave elements of both into the other. For example, in his comic opera L’Elisir d’amore, Donizetti writes music, such as to capture both comedy, and sentimentality, thus adding drama to an overall comic backdrop.

An example of such sentimentality can be heard in Nemorino’s famous aria, Una furtiva lagrima. This aria contrasts the generally sprightly mood heard and seen in the rest of the opera. Nemorino sings this when he finds out that his love potion has won the heart of Adina (when, in reality, the “love potion” is simply cheap wine).

youtube

Luciano Pavarotti takes on the role of Nemorino, and sings the famed aria, “Una furtiva lagrima”

The aria is introduced by the gentle arpeggios of a harp, as in a serenade. It is a quiet exclamation of excitement and victory, as Nemorino sings “She loves me! Yes, she loves me, I see it.”

A slow and gentle introduction. Such a mood is retained throughout the aria.

Curiously, for an aria with a successful and happy message, it starts mysteriously in the evocative key of Bb minor. It proves different from the rest of the energy and activity present throughout the opera.

In Una furtiva lagrima, Donizetti shows that, he too, is a master of clear, beautiful melodies. (Although his melodies are not as long-breathed as Bellini’s.) Again, the aria contrasts much of the opera’s energetic mood, in that Donizetti does not write in florid embellishments in the vocal line.

Simple, sequential melody, with spare embellishments.

But, in classic Donizetti style, he reserves the most florid and high-faluting embellishments for the conclusion of his aria (in which singers also often add embellishments of their own), guaranteeing immediate and deafening applause from any audience.

In the same way that the text expresses a hyperbole in terms of love (”One could die of love!”), Donizetti paints such a hyperbole by allowing the singer to freely and floridly embellish the last word of the aria.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mendelssohn’s Sechs Sprüche, Op. 79

Choral music in the nineteenth century was mostly a form of looking back to music of the past, such as Palestrina’s music for the Catholic church, the oratorios of Händel and Haydn, and the motets and works of Schütz. This is not to say that Romantic era composers wrote choral music that resembled music of the past eras (which was mostly vocal music); instead, such a “looking back” shows how Romantic era composers were inspired by the compositional techniques used by the composers of the past, and how they sought to emulate that kind of music, while still having their own sound. Indeed, it is a “Romantic” attribute to look back and long for things in the past.

Felix Mendelssohn is a prime example of a Romantic composer who looked back, and brought forth music that preserved the beauty and intricacy of the works of the past, while still producing his own distinct sound--especially in the realm of choral music.

Portrait of Mendelssohn by James Warren Childe, 1839

Mendelssohn is credited with the revival of the choral music of Johann Sebastian Bach, who today, remains an inescapable figure for any classically trained musician. Indeed, Mendelssohn’s recognition of JS Bach’s genius made Bach’s works more accessible to the wider public, beginning with a very well-received performance of Bach’s monumental St. Matthew Passion with the Berlin Singakademie in 1829. Mendelssohn’s reverence for Bach is worth mentioning, because Bach’s influences remain very much evident in Mendelssohn’s works for choir, such as his Sechs Sprüche, Op. 79.

Sechs Sprüche (Six Sayings), Op. 79 is a collection of 6 liturgical works which follow the church year, written for an 8-part mixed chorus (SSAATTBB). The composition of the work follows the reforms of King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, wherein the singing of the verse before the Alleluia in the liturgy was enforced. Each movement is short, with only twenty to forty measures, and all ending with an Alleluia. The movements are as follows:

Im Advent (In Advent)

Weihnachten (Christmas)

Am Neujahrstage (On New Year’s)

In der Passionszeit (At Passiontide)

Am Karfreitage (On Good Friday)

Am Himmelfahrstage (On Ascension Day)

*Although it was published with a different order of movements (movements were alternated according to their key, major-minor-major-minor...), the intent of the collection was to follow the church year.

In Sechs Sprüche, Mendelssohn returns to Bach’s choral writing style, with a healthy mix of chorale-like homophony, alongside masterful counterpoint, while at the same time, painting the text and music with chromatic harmonies, stretched-out dynamics, extended chords, and different overlaping textures. To illustrate this, let’s turn to the New Year reading--Am Neujahrstage.

youtube

Am Neujahrstage is on 23:08-26:00

A master of melodies, Mendelssohn opens this movement with a haunting melody based on a D minor triad, with an appogiatura on the note Bb, sung by all voices in unison. “Herr Gott, du bist...” (Lord God, You are), as if in singular proclamation of God, who is the I AM.

As the choir continues with “unsre Zuflucht für und für...” (our refuge for evermore), the choir suddenly splits, first conservatively on the word “unsre” (our)--as if illustrating a multitude of people whom God has been a refuge to--and into an even more open chord on the word “Zuflucht” (refuge)--painting the image of a strong and mighty tower, where God’s people may seek their refuge. The first phrase ends in a hopeful A major chord--the dominant of the piece, which is in D minor, somehow signalling that there is more to come--on the expression “für und für” (forever and ever), expressing the hope one has in God who is the everlasting refuge.

The opening passage in clear homophonic style, characteristic of Bach’s chorales.

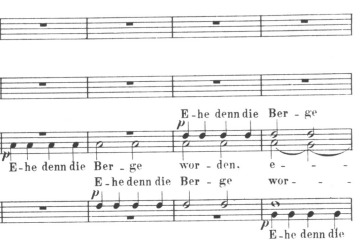

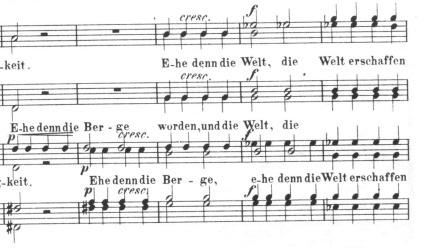

The opening phrase is followed by a series of imitative entrances. The use of imitation in the next phrases reflect the nature of the piece--New Year, alluding to the Creation, where God weaves the world from nothing, strand-by-strand. Mendelssohn uses it to paint the text, “Ehe denn die Berge worden, und die Erde und die Welt erschaffen worden...” (Before the mountains were made, and the earth and the world created...), creating an illusion of emptiness and nothingness, in which there is only God.

A series of imitative entrances building up to a grand forte, illustrating the Creation

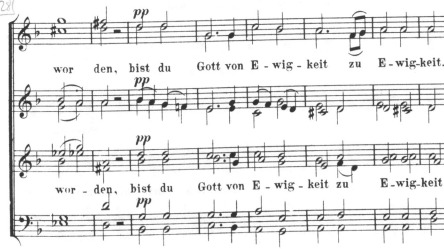

Then, in completing the phrase, “Ehe denn die Berge worden, und die Erde und die Welt erschaffen worden bist du Gott von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit.” (Before the mountains were made, and the earth and the world created, You are God from eternity to eternity.), the choir suddenly sings a beautiful F major chord in first inversion, in pianissimo. Mendelssohn paints such a picture of God’s nature--comforting, awesome, and fearful. It is as if the choir, after building up with a gradual and grand crescendo full of harmonic tension, falls awestruck at the thought of God’s eternal, ever-present nature, as with man who is truly inferior when thought of in the context of God’s greatness and vastness.

Awestruck. Mendelssohn contrasts the imitative build-up with a sudden homophonic quiet at the words ���...bist du Gott von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit.” (...You are God from eternity to eternity)

Mendelssohn then revisits his contrasting imitation and homophony, and his contrasting use of dynamics, but at a faster pace and with more harmonic tension (through the use of secondary chords, and a French sixth, among others), painting a more vivid image of the same text mentioned above.

Note the secondary dominant chord established in the second measure of the excerpt (F#-A-C-D) leading to the G minor chord in the third measure.

Mendelssohn uses a French sixth chord in leading us back to the secondary tonal level of G minor, as the choir once again sings “...bist du Gott...” (You are God...” The Fr6 chord in the context of G minor can be seen in the second half of the first measure in the excerpt (Eb-G-A-C#).

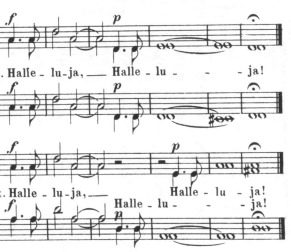

In concluding the piece, Mendelssohn once again writes the first “Hallelujah” in forte and in unison, mimicking jubilant praises from an awestruck congregation, and follows it with another chordal “Hallelujah,” but this time, in piano, mimicking the quiet, wordless praise offered by a heart that is awestruck by God.

The concluding Hallelujah of Am Neujahrstage.

Throughout the piece, we see Mendelssohn’s continual use of contrast to reflect the text--contrast in color (unison vs. chordal singing), in dynamics, and in vocal texture. The influence of Bach is evident as well, in Mendelssohn’s word-painting, text-setting, and use of homophony and imitation. Sechs Sprüche without a doubt reflects Mendelssohn’s own genius, with its haunting melodies and beautiful extended harmonies. It is no wonder why Mendelssohn remains a staple in the choral repertoire up to this day!

0 notes

Text

Romanticism: Miniature Works for Piano

The early 1800s saw the rise of the middle class, alongside for affordable and accessible music and music education. Practically everyone in the middle class owned a piano, and a piano was much easier to buy due to the advent of machines that enabled piano makers to turn out over thousands of new pianos each year! As such, the demand for music that amateur piano players could perform increased. Such is the charm of miniature piano works during the Romantic era--works that could be played by non-concert pianists, such as myself.

An influential figure in the development of piano music during the Romantic era was Fryderyk Chopin. He was a piano virtuoso, and an example of a composer who specialized in one genre, having composed almost exclusively for piano.

Chopin was particularly influential become of his idiomatic style of writing for the piano--bringing out the potential and capabilities of the instrument, and demonstrating the many possibilities with the piano. He wrote many easier works for teaching and for amateurs, as well as more challenging works for virtuosos such as himself and other advanced players.

Among his miniature works were 24 preludes (Opus 28). Like Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, Chopin also wrote preludes for all the major and minor keys. Each prelude paints a mood picture, and in each one, Chopin illustrates inventiveness in his figurations and melodies.

Chopin’s Prelude No. 6 in B minor, Op. 28 is one of the most famous and celebrated of the preludes. (My piano teacher assigned me this piece when I was in my first year of music school!) Here, Chopin assigns the melody to the left-hand, in the rich bass range usually heard in the cello. Chopin was known to have admired the cello, and my teacher would tell me that in playing the melody, my left hand must be reminiscent of the deep, rich, full tones of a cello.

youtube

Arthur Rubinstein’s brilliant performance of Chopin’s Prelude No. 6 in B minor

The melody is very evocative, and deceptively simple--a rising arpeggio settling on the tonic of the introduced chord. It is accompanied by steady repeated notes and static chords in the right hand, as if barely echoing the haunting melody moving underneath it.

For a brief moment, the melody switches to the highest line, cutting of the chromatic material in the bass.

In the third measure of this excerpt, the melody can be seen in the topmost line.

The ending proves to be incredibly tragic, as the bass line makes its final descent, with the upper accompaniment becoming more and more sparse.

Commentaries have given different labels to Chopin’s Prelude No. 6 in B minor, however, to me, Hans von Bülow captures the pathos of Chopin’s work with the title, “Tolling Bells.” Imagine church bells hauntingly accompanying the somber events happening around it--war, death, famine, brokenness, hopelessness. Such was the mood, I believe, when this piece was played at Chopin’s own funeral. (Yu, n.d., from http://www.ourchopin.com/analysis/prelude0108.html)

The work discussed above is only one among Chopin’s many great works for piano. Indeed, Chopin is a composer who has almost exhaustively explored the possibilities for the piano as we know it today. His works remain widely performed and greatly loved all over the world, by musicians and non-musicians alike. Without a doubt, Chopin is a giant in music history and in music literature.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Romanticism: The German Lied

Where the Classical Era in music saw elegance, beauty, and clarity, the era that followed it saw the concept of the sublime, with a focus on melody, emotion, novelty, individuality, and passion--the Romantic era. This new idiom was called Romanticism, and extended towards various arts, such as visual art, literature, and of course, music.

Such Romanticism in music is exemplified in the German Lied--a work for voice and piano accompaniment, and the quintessential marriage of music and poetry. True to Romanticism’s emphasis on individualism, passion, beauty and nature, the Lied often expressed 2 frequent themes: (1) An individual confronting greater forces of nature or society, and (2) Nature as a metaphor for human experience.

Robert and Clara Schumann--composers and virtuoso pianists.

Among the foremost Lied composers was Robert Schumann. For me, Schumann’s Lieder exemplified the high romantic Lied tradition, marking him as a true Romantic. He was Franz Schubert’s successor in the Lied tradition, but at the same time, Schumann did much to push the form to its limits. Here are some of Schumann’s contributions:

Voice and piano as equal partners. Relatively long sections are reserved for the piano alone, showing how the piano was not simply for accompaniment.

More through-composed works, as compared to Schubert’s strophic settings.

The use of a single figuration to convey an emotion (e.g. Descending chromatic lines for incredible sadness, several leaps for melancholy, gentle arpeggios for peace, etc.)

To illustrate Schumann’s prowess as a composer of Lieder, I have chosen two of his works from his collection, Myrthen, Op. 25. Myrthen is not a song cycle, but a collection of songs for voice and piano dedicated to Schumann’s wife, Clara Wieck. Included in the collection are 26 poem settings by different poets (in contrast to song cycles where all poems are by one poet), which Robert presented to Clara on their wedding day.

youtube

Mistuko Shirai and Hartmut Höll’s (Lieder legends, singer and piano duo) recording of Myrthen, Op. 25 (Selections).

In Myrthen, we see the two sides of Schumann as a composer. Musicologists have often identified these two sides as Florestan and Eusebius--essentially Schumann’s two main musical personalities. Florestan is lively, confident, positively passionate, and bursting with joy and excitement, while Eusebius is introspective, contemplative, and often despairing.

Schumann’s Florestan is exemplified in probably the most well-known song in Myrthen, Widmung (Dedication), No. 1, (0:00 - 2:18 in the video above) with text by Friedrich Rückert. It is the first song in the collection, and it opens with sweeping, rushing, rising and falling arpeggios from the piano, followed by a series of exclamations from the singer, expressing: “You my soul, you my heart, you my bliss, O you my pain, you the world in which I live, you my heaven in which I float...” Most likely a reflection of how Robert Schumann sees his wife, Clara, and the excitement with which he wishes to express his feelings.

The opening of Robert Schumann’s Widmung. Fast-paced arpeggios fro the piano, alongside passionate declamations from the singer

The second part of Schumann’s Widmung shows a calmer, more gentle and quiet figuration, beautifully illustrating the text: “You are my rest, you are my peace, you are bestowed on me by heaven...” To contrast the rising, fast-paced arpeggios in the first movement, Schumann uses repeated block chords with a steady bass-line, and a vocal line moving in more step-wise motion, rather than in big leaps. Schumann also makes a haunting enharmonic progression from Ab major to E major.

The second section of Robert Schumann’s Widmung. Block chords in the piano, and a gentle step-wise melody in the voice combine to provide a calmer, more peaceful effect, in line with the text.

And in a pivotal point where Schumann transitions back to the recapitulation of the first section, Schumann once again musically paints the text, “Du hebst mich liebend über mich, mein guter Geist, mein beßres Ich!” (You raise me lovingly above myself, my good spirit, my better self...) by slowing down the block chord motion in the piano, and recalling the first piano arpeggio figuration, this time, still in a soft dynamic level, and all on the dominant, heightening the anticipation, and at the same time delivering an incredible musically orgasmic moment, before finally going back to his first theme. (Pardon the term, as I find no better way of describing the power of this moment in Schumann’s Widmung.)

The transition and returning point.

Schumann ends Widmung with an homage to Schubert’s Ave Maria in the piano postlude, a perfect ending to a beautiful song of dedication for his beloved wife.

The soprano voice of the piano postlude carries the tune of Schubert’s beloved Ave Maria.

Where Widmung exemplifies Schumann as Florestan, Aus den hebräischen Gesängen, (14:35 - 19:26 in the video above) with text by Lord Byron shows Schumann as the introspective, despairing Eusebius. (It is interesting to note that this comes from the same collection as the very excited and rejoicing Widmung.)

Aus den hebräischen Gesängen (From the Hebraic Psalms) is probably the most mystical and disturbing piece in Schumann’s Opus 25 collection. It’s opening line is a lengthy piano introduction consisting of descending chromatic lines which never seem to resolve, or when the line does resolve, the relief is immediately taken away by another dissonant chord.

The piano introduction to Schumann’s Aus den hebräischen Gesängen. Notice how the accents are placed, deliberately off-setting the pulse of the song. This is meant to reflect to confusion and anguish that accompanies the singer’s thoughts, as if relief is never to be made fully available to the persona.

Unlike Widmung, the dynamic differences in Aus den hebräischen Gesängen are more varied as well. In the singer’s first few phrases alone (My heart is heavy! Oh! from the wall, get the lute, for it alone I wish to hear...), a piano entrance in the singer’s lower register is right away followed by a sforzando exclamation on the singer’s upper register.

Incredibly varied dynamics can be seen on both the vocal line and the piano line. Notice in the voice’s opening line, while the voice makes a solemn declaration, “My heart is heavy,” the underlying piano line remains uneasy and constantly moving, as if foreshadowing the ever-increasing pain that the persona experiences.

The lyrics express anguish and pain that only the sound of a lute can heal. Thus, in the second section, the piano mimicks the sound of a lute with gentle arpeggios, while the voice lays out a sweet, gently melody, which is mostly step-wise in motion and in the singer’s middle range. This paints a stark contrast to the first section, where the piano plays restless chromatic lines, and the vocal line exhibits wide leaps and extremes in dynamics.

Schumann transitions to a clear E major from an incredibly disturbed E minor. Notice the soft dynamic, and the gentle arpeggios on the piano, with only the right hand providing the flowing motion, as in a lute, and the left hand providing harmonic support through slow-moving notes.

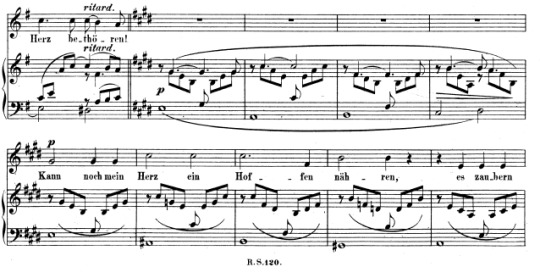

However, the persona’s relief is short lived, as in the nature of the song itself. As the persona expresses, “They [the notes] shall flow, and I shall no longer be burnt [by pain],” Schumann reintroduces the initial theme from the piano--descending chromatic lines without resolution, mimicking how the pain slowly creeps back, in spite of the music that was hoped to give relief. However, this time, Schumann extends the chromatic passage and surprisingly, settles on a gentle bass arpeggio on C major, painting a beautiful picture of melancholy and pained acceptance, as the persona sings “The notes flow deep and wild, and turned away from joy. Yes, singer it is such that I must weep, otherwise, my heavy heart will be consumed.”

Schumann extends his piano theme, and settles on a clear C major arpeggiation.

From a musical picture of melancholy and acceptance, Schumann then builds up once again, arriving to his starting key of E minor, and proceeding with a sequential progression, as the persona describes how his pain was “nourished by anguish, bearing its burden.” Schumann builds up the intensity further, as he approaches the persona’s final exclamation: “It [my heart] must break or heal in song.” Following this, the piano closes with yet more descending lines, leaving us listeners questioning, “Is the persona still to suffer?” but ultimately settles on a low, clear, and quiet E major chord, as if confirming the pained acceptance that the persona must face--the acceptance of one’s pain as the ultimate expression of the melancholy.

The two Lieder discussed above are only snippets of Robert Schumann’s genius as a composer of Lieder. The intensity of Schumann’s two musical personalities--Florestan and Eusebius--do greatly to set his Lieder apart, with their emotional intensity, high highs and low lows, and incredibly passionate, and in essence, romantic sentiments. Indeed, Robert Schumann is the Romantic epitome.

0 notes

Text

An analysis of J.C. Bach’s Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings in Eb Major, Op. 7, No. 5

As mentioned in my previous post, the said concerto of JC Bach’s exhibits the key marriage of the ritornello form and the sonata form. You can listen to it below:

youtube

Here is an analysis of the piece

1 note

·

View note