'cause in my head there's a greyhound station where I send my thoughts to far off destinations

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

He must have had some sort of Starborn blood in him, then - a distant ancestor, maybe. Or maybe his possession of the knife somehow allowed him to also bear the Starsword.

This is a red herring if I've ever seen one. I see so many people thinking Az is Starborn because of this one line that they completely miss the "or" part right afterward. This line was thrown in there to deflect attention away from Nesta being Prythian's Starborn. We know Az is not Starborn because

1) Truth-Teller never emanated with magic for him, and he's had the blade for 500 years

2) Truth-Teller and Gwydion were both tugging to get to Bryce the entire time they were in Az's possession

3) Neither blade sung for Az like they did Bryce

4) Both blades went to Bryce when she beckoned for them because they answer to a Starborn above all else

5) Az did not find the Starborn chamber in the Prison, nor could he enter it

Az is definitely something - descendent of Enalius, perhaps? - but he's not Starborn, unless he's Starborn like Ruhn.

A major reason for the crossover was for Bryce and Nesta to meet. First off, both are very similar.

1) 25 years old

2) Love to dance

3) Struggled with depression and suicidal tendencies

4) Used drinking and sex as coping mechanisms

5) Blamed for a major event happening when they aren't at fault

6) Bryce has a toy pegasus; Nesta requested a miniature pegasus illusion, which was gifted by the HoW

7) Both have been referred to as Queens

8) Both are human and Fae. Bryce is half human/half Fae, and Nesta was human before being Made High Fae.

These two fmc's met, befriended each other, and teamed up to defeat the Asteri, free Midgard, and save all worlds. It was emphasized in the crossover that Nesta willfully chose to give Bryce the Mask, rather than Az, who had Truth-Teller stolen from him. The fact that Nesta and Bryce teamed up to defeat the Asteri is significant because both are Starborn descendants of Queen Theia, who defeated the Asteri in Prythian.

1) Queen Theia defeated the Asteri in Prythian, only to turn around and try to conquer Midgard. It makes sense that her descendant in Prythian (Nesta) killed the last Asteri in Prythian, and her descendant in Midgard (Bryce) killed the Asteri in Midgard.

2) Queen Theia stole the Dread Trove from the Asteri. The crossover focused on two of those items: the Horn and the Harp. Theia gave the Harp to Silene and the Horn to Helena. Bryce, a descendent of Helena, wields the Horn. Nesta, a descendent of Silene, wields the Harp. Bryce even mentioned that the Harp was left for a Starborn to find, and she also mentioned that starlight was needed to power the objects.

3) Nesta and Bryce are the only two characters who found and were able to enter the Starborn chamber in the Prison. Bryce mentioned that only someone with the power of starlight could have found the chamber.

4) Nesta and Bryce are the only two characters to be marked by the Starborn logo somewhere on their bodies. Nesta's magic (starlight) chose the Starborn logo as her bargain tattoo, whereas Bryce's starlight left the Starborn logo as a scar on her chest.

4) I think one of the major points of the crossover was to show that what one could wield, the other could wield. Nesta and Bryce can both wield the Mask, and since Bryce can wield both Gwydion and Truth-Teller, Nesta should be able to as well.

This is all symbolized with Bryce handing Gwydion to Nesta. She didn't place it on the table like she did Truth-Teller. Rather, she handed it directly to Nesta. Bryce didn't give Gwydion back to Prythian; she gave it to Nesta, specifically because

1) Nesta's magic marked her with the Starborn logo tattoo

2) Nesta's magic guided her to the Starborn chamber

3) Ergo, Bryce gave Nesta the sword of the Starborn

It's also worth mentioning that the only females to ever wield Gwydion are Theia, Bryce, and Nesta, which also supports the theory of Nesta being Prythian's Starborn descendent of Queen Theia.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

the holy trinity of fictional men that are walking green flags

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

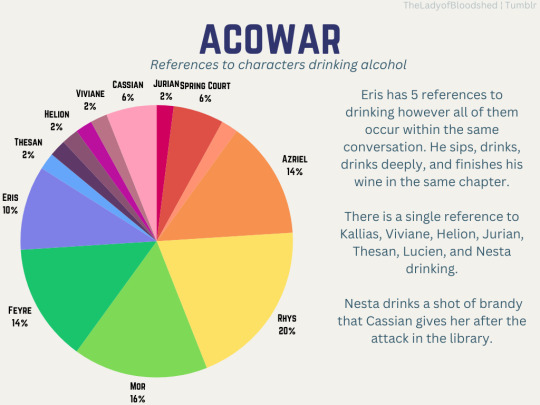

Across the entire series, there is a single reference to Nesta drinking on page. This is when Cassian forces a brandy into her hands after the Twin Raven attack and she downs it in one. Elain also presses a glass of wine into her hands on Solstice in ACOFAS, but there is no further mention to Nesta drinking it. Furthermore, there are many references to her past drinking in ACOSF, but at no point does she drink a single drop - nor does she express a desire to gamble, which is also how she ran up a debt, but was seemingly not an issue for the IC.

594 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another comic adaptation! Now is chapter 25: Jude kidnaps Cardan andd stuff happens...

Hope you like 😊

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sejanus Plinth, Lenore Dove, and the Impulsive Rebel

Both Sejanus Plinth and Lenore Dove rebel impulsively. Sejanus, foremost, enters the arena with the intention to give last rites to Marcus. He begins to act in accordance with other rebels in District Twelve, but his trust of Coriolanus becomes his downfall. Lenore Dove takes to the stage to sing about the injustice of oppression. It was not her singing that necessarily got her arrested, rather, the crowds that gathered. Both characters suffer from impulsive and emotional rebellion, which often befalls the characterization of immaturity. However, in the context of an oppressive and isolating Capitol, their Bradburian rebellions, akin to Guy Montag’s rebellion in Fahrenheit 451 and Winston’s in 1984, speak to Plutarch Heavensbee’s greater continuum of revolution.

Sejanus Plinth

In The Rebel, Albert Camus defines a rebel as “a man who says no, but whose refusal does not imply a renunciation”. In that, a rebel is someone who recognizes the authority has moved beyond the limit of its power. It has begun to encroach on the rights of others. However, the rebel is also someone who believes that there is moderation in which the authority has power before said limit. (This definition hinges on the difference between revolution and rebellion, but for the sake of the scope of this essay, I will omit Camus's broad section on the differences. It's long enough already.)

For example, Sejanus Plinth rebels against the idea of the Games and the inhumane treatment of the districts. He believes, instead of punishing the districts, the Capitol should seek to protect everyone in Panem, but he still believes in the government having power. The line for him would be the abuse of the districts.

Sejanus represents John Locke’s idea of natural law, which denotes that people are born with natural rights to life, liberty, and property. Any government must then recognize said rights, and it cannot expect obedience from people who have not freely consented to its rule.

This encompasses Sejanus’s impulsive rebellion:

“But if a long train of abuses, prevarications and artifices, all tending the same way, make the design visible to the people, and they cannot but feel what they lie under, and see whither they are going; it is not to be wondered, that they should then rouze themselves, and endeavour to put the rule into such hands which may secure to them the ends for which government was at first erected.”

In the Capitol, Sejanus is isolated in his perception of injustice. Unlike his classmates, he has insight into the humanization of people beyond Capitol borders. He recognizes they are not animals, like his classmates believe, but instead, people born with rights just like him. He must grapple with the knowledge of the harm the Games are doing and the conflicting role of being a mentor- a cog in the machine of the Games. Still, he is around people who do not perceive the “long train of abuses”, and thus feels he must convince them of the prevarications.

“Hardly rebels. Some of them were two years old when the war ended. The oldest were eight. And now that the war’s over, they’re just citizens of Panem, aren’t they? Same as us? Isn’t that what the anthem says the Capitol does? “You give us light. You reunite’? It’s supposed to be everyone’s government, right?” “That’s the general idea. Go on,” Dr. Gaul encouraged him. “Well, then it should protect everyone,” said Sejanus. “That’s its number one job! And I don’t see how making them fight to the death achieves that.” “Obviously, you don’t approve of the Hunger Games,” said Dr. Gaul. “That must be hard for a mentor. That must interfere with your assignment.” Sejanus paused for a moment. Then he sat up straight, seeming to steel himself, and looked her in the eye. “Perhaps you should replace me and assign Someone more worthy.”

He wants to be freed from the Games. He expresses this proposal to Dr. Gaul, who refuses to oblige. Yet, even Sejanus knows freeing himself from the Games is not something that would end them. Even after he no longer has a stake in the Games when Marcus goes missing, he continues to show up to classes and chime in to discussions on the Games. He rebels through free thought, as it is the only rebellion he can manage under the oppressive restrictions of the Capitol.

Returning to Camus’s The Rebel, he writes that to remain silent means to consent to the malpractice of the authority:

“To remain silent is to give the impression that one has no opinions, that one wants nothing, and in certain cases it really amounts to wanting nothing. Despair, like the absurd, has opinions and desires about everything in general and nothing in particular. Silence expresses this attitude very well. But from the moment that the rebel finds his voice—even though he says nothing but "no"—he begins to desire and to judge.”

Sejanus rebels through continuing to show up. He earnestly believes that speaking in front of his classmates and Academy staff will change someone’s mind. He believes if he can convince someone to understand, then maybe, he will make a dent in the Games. It is why Lysistrata’s speech when Jessup dies is impactful. Lysistrata, who was born and raised in the Capitol, begins to see the people in the districts beyond their characterization as animals.

“What I’d like people to know about Jessup is that he was a good person. He threw his body over mine to protect me when the bombs started going off in the arena. It wasn’t even conscious. He did it reflexively. That’s who he was at heart. A protector. I don’t think he would’ve ever won the Games, because he’d have died trying to protect Lucy Gray.” “Oh, like a dog or something.” Lepidus nodded. “A really good one.” “No, not like a dog. Like a human being,” said Lysistrata.

While I do not intend to reduce Lysistrata’s revelation to a sole factor, Sejanus’s insistence must have impacted her thoughts. She shows empathy towards his rebellious outburst after Sejanus sees Marcus in the arena. She even attempts to get Snow to console him. Snow, in fear of association, the opposite of Lysistrata, refuses.

We see more emotional rebellion in Sejanus when he attempts to give last rites to Marcus via the breadcrumbs in the arena. The rebellion of this act can be construed two ways: a boy trying to give someone passage into an afterlife, or a rebellious student attempting to humanize someone in front of the Capitol and willing to die for it. Both of these options convene in emotion.

Dying in the arena as a sole rebel will not accomplish the same messaging as working strategically with a team of conspirators. Rather, his emotional rebellion is personal and impulsive. He cannot depend on anyone to rebel with him. Again, he is isolated from any inklings of rebellion or rebellious thought leaders. Any time he attempts to bring the ideas to the classroom, someone shuts him down. Therefore, he deems it necessary to act in accordance with his own ideologies even if it means going at it alone. To him, a fleeting rebellion is better than none at all. There is no greater conspiracy other than the ideologies in his dialects: people deserve rights.

When he sprinkles the breadcrumbs on Marcus, he accepts his own death. To him, as to Camus, rebels who are willing to die recognize that some causes transcend that of a single man:

“If he prefers the risk of death to the negation of the rights that he defends, it is because he considers these rights more important than himself. Therefore he is acting in the name of certain values which are still indeterminate but which he feels are common to himself and to all men. We see that the affirmation implicit in every act of rebellion is extended to something that transcends the individual in so far as it withdraws him from his supposed solitude and provides him with a reason to act.”

Sejanus’s impulse is driven by the idea that rights (or, rites) are more important than himself. He has accepted death, even if his actions will not lend themselves to a greater movement. He acts on his own, isolated from his district and alone in his ideas. He recognizes that he must act, even if it will end in his own death. The injustices occur before his eyes, and he realizes he cannot wait to recruit more people to his cause. He has tried and failed, and now his friend is dead. He cannot wait for a rebellion. To him, there is no such thing. Of course we as readers know about Plutarch and the later rebellion, but Sejanus is not given such insight. Nor is he aware of anyone who may even consider the district citizens as humans. To him, he is alone in life and thought, and thus he accepts this as true and rebels on his own.

It is why, in District Twelve, farther removed from the Capitol’s watchful eye, he feels more emboldened. He latches on to the first signs of rebellion and devotes his life to it. He works with Billy Taupe and the rebels to try to free a prisoner, because once again, he believes people have rights. With people behind him, he has something he has never had before- a community of like minded people.

For the first time, he is no longer alone. He realizes his ideas all along can come to fruition. While his tactics are unrefined, such as drawing a map in the dirt where anyone can see, his rebellion is still appropriately limited.

Sejanus’s rebellious plot lacked a direct attack on the Capitol. While he believed in ending the Games, he set the bar lower. He likely realized the Games were too big of a target, and, unlike in the Capitol, escaping became a viable option. His goal was never to blow up the arena or free the tributes. He just wanted to get the imprisoned girl and run.

His greatest fault was trusting Snow. To him, they are brothers. He has been his confidant before, and Snow has saved him countless times. He refused to graduate unless the academy allowed Snow to graduate, too. Inasmuch, he is misled to believe he can tell Snow the plan.

For once, Sejanus found people who believed in the same things he did. Had he not told Snow, his rebellion likely may have worked. However, just like Guy Montag in Fahrenheit 451, he placed his trust in someone he believed to be his brother, and it got him killed. He felt emotionally compelled, just as he did in the arena, to give a final goodbye or an explanation. He trusted Snow, and it got him killed.

Lenore Dove

Lenore Dove’s acts of rebellion are reactionary, but still emotional. She does not act without a cause in front of her.

Assuming she was the one to cut the gallows rope and burn the flag, her actions of rebellion are always focused on one event. She sawed the rope to permit it to snap, and she burned the flag to create drama around the reaping ceremony. Neither of these events end with anything other than someone getting arrested. She acts out of necessity, but her acts are impermanent. Like Sejanus, she lacks an overarching goal and an overall movement.

However, unlike Sejanus, she is raised with rebellious media- books, free thought, and music. She idolizes the raven on the tree that can say what she desires. She admires people who can speak freely, going so far as to tell Haymitch she hopes to be able to speak her mind when she’s older:

“And nobody tells them what to say. That bird is who I want to be when I grow up. Someone who says whatever they think is right, no matter what.” No matter what. That’s the part I’m worried about. That she might be saying something rash. Or even doing something beyond dangerous words. Something the Capitol won’t warn but whip her for. The year she turned twelve, she crossed that line twice.

Yet, Lenore Dove respects the wishes of Clerk Carmine by singing only in the meadow. She complies with her uncle's wishes by refusing to play the Goose and the Common in public. She censors herself, and she will not sing in public because she “says it makes her too nervous to sing in front of people. Her throat closes up.”

However, her ultimate rebellion has her doing both things: Freely singing what she wants and gathering a crowd in the square. She immediately gathers like minded people:

“Less about what I played, more about how it drew people. Everybody’s real upset this year, so many kids. They needed a place to be together, to raise their voices. Sometimes the hurt’s too bad to bear alone.” So it wasn’t just her, playing her heart out in front of the Justice Building. A crowd had gathered. Sung the forbidden songs. “Did they say the charges?” “Disrupting the peace or something. And you know, ‘No Peace, No Anything.’”

She became, for a moment, a voice for District Twelve, who sang along with her forbidden songs. Had this occurred during the 75th Games, when tension was already high, it may have spawned something greater. Instead, with the ever present threat of the peacekeepers and propaganda in the square, the people complied by dispersing without issue. There was no compelling call to rebel. It was, as Camus says, “Rebellion is, by nature, limited in scope. It is no more than an incoherent pronouncement.”. She struck a spark that did not catch. However, in doing so, she placed herself, literally by being on the reaping stage, on the same level as the Capitol’s propaganda. She demanded respect for the ideas present in her songs.

To return to Camus:

“The act of rebellion carries him far beyond the point he had reached by simply refusing. He exceeds the bounds that he fixed for his antagonist, and now demands to be treated as an equal. What was at first the man's obstinate resistance now becomes the whole man, who is identified with and summed up in this resistance. The part of himself that he wanted to be respected he proceeds to place above everything else and proclaims it preferable to everything, even to life itself. It becomes for him the supreme good.”

Lenore Dove’s emotions drive her rebellion, and, like Sejanus, she doesn’t think about the consequences until they occur:

“No, darling, that’s not how it went down at all. I overstepped, just like my uncles always warn me about. I lost my temper and started hollering and now you’re — oh, Haymitch . . . I don’t want to be on this earth without you.”

Both characters do not consider the consequences because they act according to the urgency of the situation. They recognize no one else is making a move to rebel, and they rebel without support, because to them, none exists. To them, it is better to rebel than to sit by and watch, even if the fall out is worse than staying silent.

Haymitch says it best:

“It’s not like she’s part of some big conspiracy, so, hopefully, they won’t use methods to force her to talk. Just view her as an emotional sixteen-year-old whose boyfriend got reaped.”

She is not part of some “big conspiracy” because she is not given the opportunity. To both, there exists none. There is not even a chance, nor the liberty of joining. Their acts, then, are often mischaracterized as immature. Rather, the existence of the acts themselves is enough of a threat for the Capitol to silence them. Sejanus’s intrusion into the arena is never shown, and Lenore Dove is arrested. Their acts are significant in themselves, as they exist as moments of rebellion. The existence of rebellion itself is dangerous, as Drusilla says:

“You can’t say that!” Drusilla protests. “You’ll spoil the brilliant work I did covering up the riot!” “What riot? Woodbine ran and your people shot him.” “I know a riot when I see it! Never mind. That’s forbidden. It won’t win you any points with the audience anyway. They’ll respond to a bad boy, not a rebel. You need to be naughty, not dangerous.”

Any instance of rebellion is dangerous for a tyrannical authority, monumental impact or not.

Bradburian Rebellion

Both Sejanus and Lenore Dove rebel in a very Bradburian way- impulsive, emotional, and immediate. In Fahrenheit 451, Guy Montag begins to read directly from banned books, one in the same as Lenore Dove’s banned songs. Both acts ultimately lead to stamped out embers of rebellion. Montag’s fruitless rebellion results in the death of an innocent man. Lenore Dove’s rebellion results in a fortification of the state. Through her, the peacekeepers send a message of free speech and free thought are not allowed, as they disturb the peace. Sejanus’s rebellion culminates similarly to Montag’s in that he ultimately trusts someone who betrays him:

“Millie?” He paused. “This is your house as well as mine. I feel it's only fair that I tell you something now. I should have told you before, but I wasn't even admitting it to myself. I have something I want you to see, something I've put away and hid during the past year, now and again, once in a while, I didn't know why, but I did it and I never told you.” He took hold of a straight-backed chair and moved it slowly and steadily into the hall near the front door and climbed up on it and stood for a moment like a statue on a pedestal, his wife standing under him, waiting. Then he reached up and pulled back the grille of the air-conditioning system and reached far back inside to the right and moved still another sliding sheet of metal and took out a book. Without looking at it he dropped it to the floor. He put his hand back up and took out two books and moved his hand down and dropped the two books to the floor. He kept moving his hand and dropping books, small ones, fairly large ones, yellow, red, green ones. When he was done he looked down upon some twenty books lying at his wife's feet. “I'm sorry,” he said. “I didn't really think. But now it looks as if we're in this together.” Mildred backed away as if she were suddenly confronted by a pack of mice that had come up out of the floor. He could hear her breathing rapidly and her face was paled out and her eyes were fastened wide. She said his name over, twice, three times. Then moaning, she ran forward, seized a book and ran toward the kitchen incinerator.

Montag, Lenore Dove, and Sejanus Plinth are all impulsive rebels. Their emotions and personal constitutions compel them to act. In every case, they do not fight with a greater cause, because the rebellion is so subdued they perceive no other choice than to act alone. They see the urgency in their situation, and they act accordingly. Often, as we see in both 1984 and Fahrenheit 451, this type of impulsive rebellion does little in the grand scheme of things. It is fleeting and, in the case of Winston, completely quelled into naught. However, in the context of Plutarch Heavensbee’s continuum, every act of rebellion is important, even the fleeting one-off ones. To put it simply, it all adds up.

As Camus continues:

“Rebellion is, by nature, limited in scope. It is no more than an incoherent pronouncement. Revolution, on the contrary, originates in the realm of ideas. Specifically, it is the injection of ideas into historical experience, while rebellion is only the movement that leads from individual experience into the realm of ideas. While even the collective history of a movement of rebellion is always that of a fruitless struggle with facts, of an obscure protest which involves neither methods nor reasons, a revolution is an attempt to shape actions to ideas, to fit the world into a theoretic frame. That is why rebellion kills men while revolution destroys both men and principles.”

Yet, all three characters rebel due to hope for a better future, because hope is all they have:

“The slave and those whose present life is miserable and who can find no consolation in the heavens are assured that at least the future belongs to them. The future is the only kind of property that the masters willingly concede to the slaves.”

The purpose of the Games, according to Snow, is to give the districts hope, and they do. To Sejanus and Lenore Dove, they hope for a better future, and they both rebel under the idea that their acts may have no greater consequence than an “incoherent pronouncement”, and yet, they are compelled to act.

Because, finally, as Camus says:

“Better to die on one's feet than to live on one's knees.”

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my favorite moments in the original trilogy is when Nesta and Elain teamed up to kill the King of Hybern. Not only because they were the two characters least likely to do so, but because that entire scene showed that Nesta loved Feyre and Cassian enough to die for them, and that Elain loved Nesta enough to kill for her.

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

BRIDGERTON SEASON FOUR, SNEAK PEEK (x)

Luke Thompson as Benedict Bridgerton and Yerin Ha as Sophie Baek

492 notes

·

View notes

Text

BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER REWATCH -> Lover's Walk (3.08)

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

And that's a wrap on my official VM art!

I am still so so amazed by all of this.

We have truly come full circle: It was art of Vax that first made me watch CR and now here we are years later, me drawing official Vax?!Thanks for all the intense critter support over the years, folks < 3

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

umm?? apparently RY said the prophecy by Taylor Swift is dain's song??

THE CHORUS???

"Thought I caught lightning in a bottle

Oh, but it's gone again

And it was written

I got cursed like Eve got bitten

Oh, was it punishment?

Pad around when I get home

I guess a lesser woman would've lost hope

A greater woman wouldn't beg

But I looked to the sky and said

PleaseI've been on my knees

Change the prophecy

Don't want money

Just someone who wants my company

Let it once be me

Who do I have to speak to

About if they can redo the prophecy?"

I'M REALLY UPSET NOW?? UNPOPULAR OPINION BUT I LOVE HIM AND I WANT THE BEST FOR HIM PLEASE RY DON'T KILL HIM😭😭

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many people have made the point that Sarah J Maas describes her female characters and characterizes them in a manner that feels specifically “male” and objectifying. I believe that the kind of strange male spectatorship she employs in her writing is meant to be one of the pleasurable elements of the stories she writes and one of the features that makes her writing popular. Here is a passage from John Berger’s book Ways of Seeing that explains what I’m talking about.

“Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed is female. Thus she turns herself into an object of vision: a sight.” (John Berger, Ways of Seeing)

With this in mind, I understand Feyre and Rhysand’s relationship as one that gives the reader-identified character a kind of pleasure as a result of them being objectified and sexually admired by a high-status figure. The exhibitionism that Mass frequently uses to create sexual tension (ex. Feyre being scantily clad and groped under the mountain and portrayed as Rhysand’s “Harlot” in Hewn City) operates both as a way for the male love interest to demonstrate his pride in objectifying the heroine’s body, and establish her status in relation to his. In Hewn City, Rhysand’s reactions add doubly to this pleasure when he violently attacks Keir for insulting Feyre. It does not matter if the action was illogical and contrived, what matters more is that through this action the reader can see themselves being looked at and reacted to by male characters. This in turn strengthens the reader-identified character’s worth as a desirable object.

74 notes

·

View notes