Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

A carrier bag theory of garments

Across from me on the subway, a man wears a black hoodie with three polo players embroidered on it in gold thread. This imagery is machine-wrought, capturing the stripes on the polo players socks with the tapered angle at which the thread is stitched to catch the light. The actual fabric of the garment is thick. With the hood up, such a thing must feel like a cushion against the world. Catching sight of it on my morning commute, I drop through time and place.

Every garment is an archive. To borrow Ursula LeGuin's analogy for writing, it is a carrier bag; a gathering of references, exchanges, thefts, migrations, contaminations and frictions. A garment tells as many stories as there are threads woven into it.

This one calls upon Hip Hop and street culture, the mainstreaming of athleticism into fashion. And more. And also.

Also the vernacular signaling of Connecticut country club culture. Polo Ralph Lauren initially positioned itself against the boys who began stealing their garments and collaging outfits that mixed classes and (sub)cultures to generate a new hybrid of conspicuous consumption all their own. The elite brand later embraced what they had initially missed: an opportunity to scoop up more forms of cultural capital.

Also the game of Polo, Ralph Lauren’s logo and namesake, which was being played in Persia when Britain was just a rainy, underdeveloped backwater. A 2000 year old game appropriated by the British and turned into the signal of class and social standing in a Eurocentric reordering of the world.

Also a 19th century Asante drinking bowl made from calabash woven through with strips of beaten gold, used to catch the palm wine that an Asantehene let spill over his chin in a ritual gesture of abundance and conspicuous consumption.

Also the deep artisanal craftsmanship that has gone into the vestments of the Church, the glory of god rendered thread by thread. These garments were born out of the iconographic language of crests and armorial ensigns, which were in turn born out of European medieval tunics worn to declare a knight’s loyalty in battle.

Body flags of allegiance, and orders of defiance, in the slippage of capital – financial, cultural, aesthetic.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Schin Hakchul, Scissors, 1974 Ink, scissors, and colored thread on mulberry paper (hanji) on canvas. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (on display at the Guggenheim museum)

Scissors

I’ve always liked scissors. I collect them – small, large, sharp, blunt, decorative or coldly utilitarian. The sound that scissors make, of two sharp blades sliding past one another severing the fibers of paper or cloth, is deeply satisfying.

My childhood nickname was Mac the Knife, in deference to my sharp tongue. As a teenager, I would get up at 5am to make my punk outfit for the day, hacking through yesterday’s garments to reconfigure a textile with staples and big ugly stitches; these days, I cut through printed out drafts of anything that I write with the same ruthless abandon. In editing, I am Dr Frankenstein, hacking and reassembling the flow of language into some kind of monstrous argument.

But these scissors, so carefully wrapped in thread by Korean artist Schin Hakchul, block their sharpness. It is a situation full of tension: you could cut the thread with the scissors, but at a certain point, the scissors are overwhelmed by layers and can no longer move. In the same way, grass conquers the mountain. The softness is a kind of swaddling, an enforced hug that might blunt my sharpest edge.

0 notes

Text

CLEAVE

When I made it, I imagined this piece as my own tombstone. I found it recently in the long grass on my father’s farm. Once a white ceramic slab painted in slip, it’s now more like bones than I ever could have imagined. This lump of clay places me on a timeline. It’s a reminder of a moment in my past when I looked ahead to the moment of my death, that I would one day be folded up, put into a box and tucked somewhere in the soil. The future coming towards me.

I remember crying while working on this piece, though I don’t remember why. A friend told me “when you go home, make some noise when you cry.” I had been holding in the ungraceful, noisy part of sadness, choking on it. Soon afterwards, this same friend would hold up a scan of her own bones speckled with black spots; tiny holes in the fabric of time through which the rest of her would ultimately pass. I’d speak at her funeral, black stilettos in one hand with my bare feet on the ground.

I’m told that the word “cleave” comes from “clay”. “Cleave” is actually two words, with two etymologies converging on the same spelling and pronunciation. These two words in one body are opposites: to split apart and to stick together. The latter has clay at its root. Clay cleaves together. Death cleaves apart.

0 notes

Text

Spiders are not beloved like the bees

At Dia Beacon, Meg Webster’s pieces marry geometry and organic materials. Cones of salt, cubes of forest earth, nests of branches, and a large curving wall of beeswax.

The wall wrapped itself around me from meters away, reaching out and holding me in its thick, warm scent. An olfactory embrace.

Bees are mythical creatures. It’s hard to get away from all that they represent – their longstanding metaphorical connections to ideas like industry and community; they make stuff, they move together. Right now, it’s early March on the east coast of North America, they are harbingers of warmth––signals that life is returning after winter. Some part of me, every year, fails to believe in spring. When the bees arrive, something in me matches the tempo of their wings. The scale of this wall amazes me, because of its debt to tiny insects. Madison comments on how many bees must have contributed to this human-scaled architecture.

And it makes me think about the garment made of spider silk that I have just been reading about, which is in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum. Millions of golden orb spiders unrolling filaments from their spinnerets, which are bundled and twined together, then woven and embroidered into a garment that looks like it has been died with turmeric or saffron. This rich yellow gold is the colour of the thread itself.

There were golden orb weaving spiders in my grandmother’s garden (perhaps not the same kind as the Madagascan spiders that wove this silk). Their glittering webs would appear overnight and tremble in the morning dew, the coolest part of the day before the summer heat would bleach the sky. She was careful not to break them, even when they’d make the web like a gate across the garden path: we’d need to go off the path, through the shrubs, find a way around.

The spiders resist industrialization, so they are not beloved like bees.

youtube

0 notes

Text

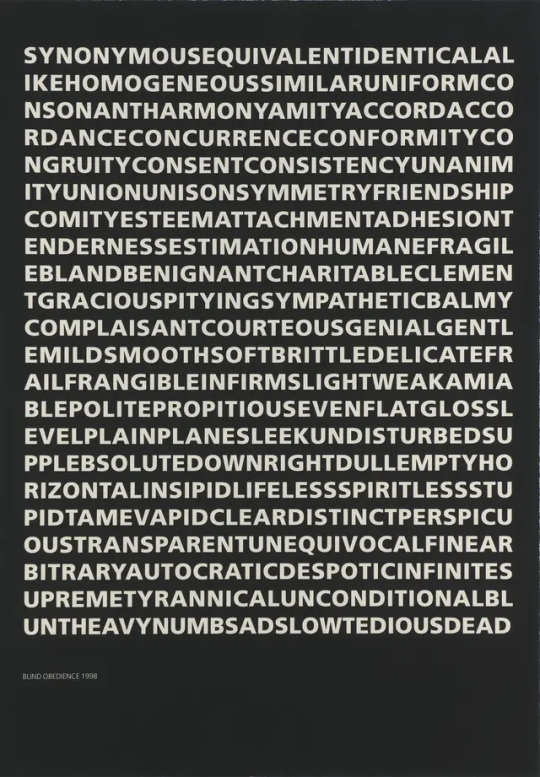

Blind Obedience

At the time of writing, 17,700 Palestinians have been killed by Israel.

Mike Parr’s relationship with Anna Schwartz (the person and the eponymous gallery) ended in a two-sentence email on Friday, after the artist inscribed, among other things, the words ‘Israel’, ‘Palestine’ and ‘Apartheid’ on the walls of the gallery during a performance piece.

The inscription would not have come as a surprise: Parr has long worked with language in a way that is pointed and political. A piece from the 1990s, titled ‘Blind Obedience’, was made by opening the thesaurus and looking up the word Synonymous, which yielded the word Equivalent, which in turn yielded the word Identical, and then Alike, and so on, until at the bottom of the page, he arrived at the word Dead. As one word leads to another word, meaning is dragged and transmitted by contact. And what is language if not contact and transmission? But with each synonym, we are moved towards that last word. This is a kind of contact print. I’ve never been sure what the Blind Obedience of the work’s title refers to: meaning, and its traces? The flow and pull of language? The tyranny and indispensability of finding another word to say what you mean? The way meaning is never wholly under your control?

Anyway, the work seems to come back into view in a different way now. It foregrounds the way that language drags and charges itself up in contact, starting fires everywhere. If each word is an ember of meaning, the proper noun ‘Israel’ is a gale-force wind that blows meaning into a devouring fire. By the time he finished painting over the words with red paint, the room had caught alight.

A friend has a reaction that I do not expect. She feels the violence of Hamas ‘in her bones’ and worries about the rising tide of antisemitism. She takes her opposition to Israel’s immense violence for granted, but something else is happening beneath the surface of her skin. In this exchange, the word-ember is Context and it catches fire pretty fast. This is because in the mental thesaurus that is alert, always, to what is not being said, the word Context abuts Excuse, Prevaricate, Downplay, Permit, Condone [violence], Endorse [genocide]. To have context, in all its messiness, is an ethical way to live, I think. But ethical does not equal painless, or even kindness.

To her finely calculated credit, Anna Schwartz has not censored this work. As she points out, she has left the exhibition on display, though the word-embers were obscured, during the performance, by that layer of paint (though remain visible in the video of the performance). It also must be said that the artist wrote other things on the wall, including a painful description of Hamas’s actions on October 7. Things that we thought went without saying can no longer go unsaid. And yet, despite Parr’s deference to naming the brutal particularities of October 7, the word ‘Apartheid’ appears to be what caught fire. Perhaps this is because Apartheid has a specific meaning with legal consequences under the UN Apartheid Convention, and Amnesty International published a damning report on Israel’s policies in this respect last year. Perhaps, too, because it connects the Israeli State to the brutal white South African regime from which the term originated: a contact print of another kind. Deriving from Afrikaans, Apartheid combines the self-evident apart (apart) with a suffix heid (hood). The suffix ‘hood’ functions here like it does in ‘brotherhood’. The ‘brotherhood’ of the nation state is formed in its apartness from the other, from those stripped of any semblance of civic and political rights, and in the rhetoric that flared up so immediately after Hamas’ attack, which painted all Palestinians as culpable, thus authorizing collective punishment of over two million people.

There is always danger in drawing analogies between one cataclysmic violence and another, in collapsing the specificity and contingency of each time and place into a singular evil. But there is equal danger in failing to recognize the patterns that recur across different colonial systems. And, even holding the specificities of each conflict in mind, how else could Israel’s policies and practices possibly be described? They built a wall – not just an epic concrete structure but an exploded, polysemous infrastructure that is everywhere all the time (see Israeli scholar Eyal Weissman’s lecture The Politics of Verticality at the AA School of Architecture for a breakdown of this). It wends its way into every aspect of people’s lives, from checkpoints to policies defining nutritional humanitarian minimums, to imprisoning and killing teenagers who throw stones at one of the most powerful and sophisticated militaries in the world.

It’s worth noting that in being “sickened by the hate graffiti inscribed on the wall” Anna Schwartz declared Mike Parr in breach of her “principles of anti-racism”. It’s important to keep track of the ideas in circulation here, the meaning that the language drags: definitions of graffiti typically include words like ‘unauthorized’ and ‘illicit’ implying that the artist came in uninvited and wrote these words without asking. But the gallery promoted this act of writing as a public performance, part of a large-scale exhibition of the artist’s work. Permission was retracted only after the words caught fire. It's worth also thinking about the gravitas of words like 'sickened' and 'hate'. Sickened by what? Hate for whom?

The gallerist has been described as a kingmaker. She is powerful in her context. Being powerful in one context does not render one invulnerable, but the balance of power must always be measured carefully. The artist, too, is a powerful figure within his context. He is successful, controversial, widely collected by institutions and safely ensconced in his Sydney home. I have, at various times, struggled with his eagerness to put himself in the frame, to absorb and reconstitute the suffering of others as a political gesture, because sometimes this ends up displacing, rather than centering, those others whose suffering we really must apprehend and wrestle with.

Anna Schwartz’s gallery took a cut of the sales of Mike Parr’s works ‘Close the Concentration Camps’ and ‘UnAustralian,’ both of which indicted Australia’s carceral archipelago of refugee detention centers, likening them to strategies deployed by the Nazis. But that was then, describing Australia, and this is now, describing Israel. More powerful than any one person, Israel's military infrastructure nevertheless relies upon millions of reactions just like this one. Shaped by the trauma that preceded its founding, it bodies forth a wound that is handed down generations, nurses a hypervigilance that makes words into weapons. Schwartz herself described Parr’s words as a kind of violence wielded against her, saying “I can’t work with an artist who’s prepared to hurt me to that degree”. And it’s true that words can hurt. This isn’t the trauma olympics, I’m not interested in diminishing people’s pain. But we should never forget what’s at stake, and who is most vulnerable. Words have real power, they move money and reshape careers. They also move bulldozers, tanks and missiles. We begin with a word – maybe it’s as seemingly innocuous as ‘context’ or as loaded with historical associations as ‘Nazi’ or ‘Apartheid’. Maybe it’s the chilling phrase ‘human animals’, a harbinger of mass slaughter. With blind obedience, it doesn’t take us long to end up with ‘Dead’.

By the time I finish writing, 18,200 Palestinians had been killed by Israel.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the frick, it’s the sleeves that hold my attention. Van Dyck, Vermeer, and Holbein. Lace cuffs folded back over black. Red — is it velvet? — rumpled and gathered. Hands gesturing, poised in the air like small birds changing course, or resting on a tumble of fabric, languid like cats asleep on freshly washed but not yet folded laundry. Bodies encased and folded up in drapery. They worshipped drapery — the body a place to celebrate the fold.

It’s always surprising to discover the imperfections. Being from far away, I’m so used to seeing these images printed in expensive catalogues, sealed in the authoritative gloss of reproduction. It’s easy to forget they’re imperfect and that’s what makes them real. Behind one lace cuff a block of black paint, the background hedged in afterwards. Surely what is behind should be painted first? Sure the room, full of space before the woman arrives on the canvas. But no. The room begins with her, the rest falls away.

Or Holbein’s portrait of Thomas More, who has the lips of an ex. The whole thing seems so complete, like it was never touched by a human hand. But tiny pricks of black and grey pick out stubble, collapsing back into paint on the tip of a brush. It’s both a relief and a disappointment; equal parts enchantment and the slight downgrade of an ideal. It’s only in the flesh that the image falls into the material,perfectly imperfect world.

1 note

·

View note

Text

What I said at my grandfather’s funeral

It’s a strange thing, the way that we delay grief. I can be impatient with it, wanting to lance it, to be in it and then done with it. But it has taken some years to come back around to this, my grandfather’s death. It happened because, for the first time since his funeral, I went into his library. Not a big grandiose library, but a small room in a suburban house with a window looking into the carport, an ironing board, a broken lamp, the sound of the television from my uncle’s adjacent room. Here I found books, and found that he died before I had the chance to have any conversations about them. So here is what I wrote back then.

I’m going to speak about two things about my grandfather that were important to me. And in the spirit of Neville, I am going to go on for a little longer than you would like, to invoke some etymology and poetry, to overstay my welcome in the conversation just a little, in an act of wry homage that I hope you will understand as an act of love.

Indeed, I don’t think he’d be too offended if I use the word pedantic to describe him today. I use it knowingly and affectionately, for it’s one of the qualities he gave to me. So, as his proudly pedantic granddaughter, let me take this moment to tell you—my captive audience—that the word ‘pedant’ is of Latin origin, deriving from roots that mean leader of children, teacher. And teaching was in his blood and his bones. The pejorative use of the word pedantic is first attest-ed in John Donne's "Sunne Rising," where the poet bids the morning sun let his love and him linger in bed, telling it, "Sawcy pedantique wretch, goe chide Late schooleboyes." I like to think of him as this sawcy pedant, an insistent and persistent imparter of knowledge, whether re-minding us that ‘yum cha’ means ‘to drink tea’ or giving impromptu spelling exams, or begin-ning every other sentence with the words “Macky did you know…” If I did know, it was always because he had already told me.

He was autodidactic––and he would have liked me using that multisyllabic word. He had a great love of learning and of literature. Late in life, he was teaching himself Latin, writing (or planning on writing) a novella about the life of his dog, reading newly published books on history until his eyesight and the tremors got too bad.

He ate knowledge up. He was a know-it-all in the richest, most determined sense of the term. He wanted to know it all – he had a great ambition to absorb history, language, poetry and literature. He wanted us to learn from history’s mistakes (so as not to repeat them) and he would recite poems from memory. One of my strongest memories is of him reciting The Rime of the Ancient Mariner in the car, on our way somewhere in the flattening Brisbane summer heat. I remember his rhythmic, emphatic—even ardent—evocation of the skeletal ship crossing the sun:

And straight the Sun was flecked with bars, (Heaven's Mother send us grace!) As if through a dungeon-grate he peered With broad and burning face.

He slowed down on that last line, willing me to absorb and appreciate the simple force of those alliterative words, emphasizing the iambic meter of the poem’s quatrain—as you can tell there is a good dose of my grandfather in me right there.

I didn’t inherit his photographic memory, but I did get his deep love of poetry, his appreciation of language, and most importantly his willingness to iterate and reiterate. The recitation of poems from memory was something of a ritual for him – a walking through that was also a wearing into the grooves of language. It was important to him that the words were said repeatedly, for iteration is remembering, remembering is learning, and learning was how he became himself.

He also became himself through his political commitments, which were closely bound up with his understanding of history.

He came from a family that had profoundly different politics to him. He wore his left-wing, socialist tendencies as a badge of distinction, a mark of difference that represented a triumph of his independent spirit. He was emotional and impatient when it came to politics and I loved him for that. His uncompromising left-ness manifested in his rage when he learned that Joe Bjelke Peterson was to get a state funeral, his pointed irritation at the conservative decade of John Howard, his cantankerous despair at the election of Tony Abbott and then of Donald Trump—which is the last politics he and I discussed. He was committed to a politics that wanted to see the poorest lifted up and given the same opportunities as the wealthy, which believed in our capacity to do better by each other, to be a fairer society. His politics was a deep part of his identity.

Some years ago I borrowed something he said to me in the parking lot of a local shopping mall: “See you at the barricades, kid” for the title of an exhibition. In the catalogue essay I wrote that this was his way of inviting amity through shared resistance. In that catalogue I missed a lot, and today I have also missed a lot: I do want to mark his sense of humor, his cheekiness, his vigilance when it came to his grandchildren. When my sister Rose fell into the pool in the backyard before she could swim, he leapt up and dived in fully clothed – shoes and all – an act which destroyed his watch (though lets face it, he had a rather large watch collection).

Anyway… He invited me into the fold of his politics and his love of literature and learning, and I want to honor that by farewelling him on his own terms: see you at the barricades, grandad.

0 notes

Text

The smallest heartbeat

I’d been cycling to the point of nausea. I was sweating in the sun, and my legs shook when they stopped pushing. The lamb’s call sounded so different than its mother’s, smaller and yet somehow still louder. I gave it a wide berth; I walked around it as if I was just passing by, looking into the distance. It didn’t flinch, it was solely focused on getting through the fence. So I walked up behind it and scooped it up. Its heartbeat was fast, and it shook me to realise that this is probably how fast such a small animal’s heart beats all the time. I’ve never understood why.

The innocence of Zurbaran’s lamb must come from this small heartbeat. The little thing didn’t struggle at all, its long legs hung down. The thing that’s most amazing about the picture is the way the light slants across the creature’s wool, tight but also somehow soft coils, like clouds or ripples or the side of a mountain. It is absolute, placid acceptance of the end of its life. It could not be more worried than the mountain, but it knows what will happen. This acceptance makes it so much harder to look at.

The lamb started struggling only when it got close to its mother, who walked backwards away from me. Both their sounds ceased when its hooves hit the ground, running now, tucked quickly out of sight.

0 notes

Text

As if.

On the news this morning, “these attacks appear not to be racially motivated.”

As if six women out of eight all just happened, incidentally, to be of Asian descent.

As if this man would tell us he was racist.

As if the sexualization of Asian women wasn’t violent.

As if it wasn’t a weapon wielded by white culture.

As if sexual violence and rape weren’t tools of empire.

As if there weren’t centuries of coercive concubinage.

As if there weren’t centuries of fetishization fuelled by hate and need.

As if white men didn’t exorcise this shame through the bodies of these women.

As if they didn’t use bodies and then dispose of them.

As if white men weren’t told they could take whatever they wanted.

As if American citizenship weren’t linked to the sexual desires and repudiations of white men.

As if the Expatriation Act of 1915 didn’t strip Asian women of their American citizenship when they married Asian men.

As if orientalist paintings didn’t sanction and consecrate these murders.

As if the people with all the power hadn’t cultivated a link between a deadly virus and racial identity, thus authorizing this violence. Calling upon it, breathing life into it.

As if lust and desire and intimacy weren’t shot through with transgression and narratives of contagion and racial contamination.

As if the front page of the New York times didn’t turn this into a true-crime column.

As if society hadn’t given the keys to a white man with a gun.

0 notes

Text

Every Rape in the Met Museum #4: Stone and water

Battista di Domenico Lorenzi, Alpheus and Arethusa, 1568 – 70

“the biggest theme in Ovid, other than metamorphosis, is rape. Jupiter rapes Io, a mortal woman, and turns her into a cow. Because Ovid’s women would bear no husbands, their pursuers change them into animals and submit them to husbandry.” (38) - Summer Brennan

Arethousa is fleeing the river god Alpheus. She crosses the sea but she can’t shake him. Just as she is captured, she implores Artemis, and is turned into an underground spring. In Ovid’s Metamorphosis, women fleeing violence become nature. They are transformed into streams, trees, islands. Arethusa’s description of becoming water begins with sweat: “A cold and drenching sweat broke out and rivulets of silvery drops poured from my body; where I moved my foot, a trickle spread; a stream fell from my hair; and sooner than I now can tell the tale I turned into water.” Alpheus also changes and, undeterred, mingles with her waters. But it is her transformation that we feel in the writing.

The museum’s text for this work is passionate and painterly. You can feel the author stroking the statue with his words, running his hands over this abraded surface, anticipating her sudden dissolution, marveling at the sculptor’s ability to transform rock into flesh. It is only one among thousands of unmoving stone bodies in the museum: this statue used to exist in an underground grotto with water dripping flooding flowing around.

Stone can do a lot of things. A heart of stone is cold and unbeating. It cannot care. A stony face is unyielding. It gives nothing away. When we say that something fleshly has turned to stone, it is our way of saying that it has lost its mobility and warmth. When we describe the sculptor’s work, the greatest admiration is reserved for those who can inch stone closer to flesh, to make it appear to be on the precipice of movement, warm with the cellular activation of blood and muscle. The Pygmalion is a story of man’s desire to make stone flesh: this wall label is a story of man’s admiration for fleshly stone.

But stone is not really the antithesis of flesh. It is a conductor of heat. Pick up a stone, fold you palm over it, walk around with it in your pocket. It will move along with you, become warm like your flesh.

Her attacker is holding a pitcher at his side, a vessel to capture the water that she is about to become. His face is calm and determined, her flight is a mannered turning away. He has thrown his arm over her shoulder, placing his hand right between her breasts. She tries to pull it away.

Sometimes someone’s hand lands on you and turns you to stone. Sometimes someone’s touch can turn you to stone, make your skin solitary, make your body unable to move.

Better, perhaps, to be like Medusa, who turned men into stone when they looked in her direction. Medusa used to be beautiful. But when she was raped in Minerva’s temple, Minerva punished her, giving her a deadly countenance. A punishment that was also a form of protection.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What hangs in the same space

In his tour of the new collection install, he talked about how Ana Mendieta was attractive, and would do things to disrupt her beauty, like pierce her skin above her hairline and let the blood flow over her face. Even though I could tell he loved the work, it didn’t make much sense to him.

A few minutes later, he stood upon a floor-piece by Carl Andre and talked about how Andre had worked in a railyard, ‘shunting’ things around, and how he used to come to openings in his worn out workshirt. This, I could see, made a lot of sense to him. The way he moved his hands and shifted his weight when he talked about it, his body knew that language.

But I wondered if a curator would ever stand in front of a piece by Mendieta and shift the weight of her body or turn her head in recognition of the gesture of bleeding. Mendieta showed us that she knew how to bleed. I am yet to see a curator let on that she, too, has flinched. Because sometimes you can be pretty to survive, but you always have to turn it on a dime.

I am yet to hear a curator say––you know that feeling, when the man who loves you also hates you? When the man who covets your beauty also resents it? When the man who shunted things around a railyard is standing between you and the door?

How perverse that we hang their works in the same space, as though this history wouldn’t walk between them, as though it wouldn’t haunt all the women I know.

0 notes

Text

I’m looking at you looking at me. You are looking at me looking at you. But our eyes don’t ever meet. The gaze is diverted, rerouted, through the lens, through the screen. To look like I’m meeting you here, I have to look into the camera’s eye, not yours, I have to stare at this little green light. Surely, it’s only a matter of time before they find a way to map the lens onto your eye on the screen. We’ll meet there, then. Will that make me feel less like your gaze is hitting the side of my face?

There are gazes that are conditioned on being unmet. That kind of cannibalistic looking can only go unseen.

In the zoom meeting, you have to accept that anyone could be looking at you intensely and you would never know it. We are all staring at a screen. In person, you can feel someone’s eyes upon you. In here, in this room, my gaze hits the side of your face.

0 notes

Text

Every rape in the Met Museum #3: Hades in the bedroom

Marriage chest (cassone) ca. 1480–95. Italian, Florence or Lucca.

The museum text contextualizes this marriage chest by describing the room in which it would have lived: “Italian inventories and descriptions of Renaissance-period households document the importance of great chests in the main bedchamber, or camera. This room was the center of an upper-class woman's existence, as she was encouraged to live mostly indoors and to avoid lingering at open windows or in the semipublic courtyard of the family house.”

The word ‘camera’ stands out here, for its unusual use. It comes from Latin and once described an architectural space, an internal room with an aperture, which only later came to denote the dark chamber that holds a light sensitized surface upon which a photograph is imprinted. The window opens for a second only. It is a controlled exposure.

...

The chest depicts the story of Persephone.

Imagine this: you are to be married. You are going to enter the dark chamber and to be discouraged from sitting near the window. You inaugurate your marriage with a chest showing the story of Proserpina. Its panels show Proserpine’s mother Ceres’ restless search for her daughter that lead her to neglect the crops and starve humanity. This accounted for the onset of winter as the earth turned and grieved.

...

The museum text describes these scenes as “tales of love and fertility” and notes its popularity at the time despite religious disapproval. The text imagines the abduction as romantic, a love story. But it is also a story of loss, the detachment of a daughter from her mother. The mother, here, has agency. She holds humankind hostage with the winter of Persephone’s absence, and in so doing secures her daughter’s partial return.

The museum text raises a difficult question: can we imagine this abduction as romantic? We don’t hear Persephone’s voice: this battle is fought between mother and husband, and the mother’s fecundity (her ability to make the crops grow) is a weapon.

Persephone’s consent, or the possibility of her refusal to consent, seems to be out of the picture. We only know that she eventually moved back and forth between two worlds, governed by two competing authorities, one patriarchal and the other matriarchal.

...

Not all mothers feel Ceres’ loss. In Landscape for a Good Woman, Carolyn Steedman writes “And we were certainly not Demeter and Persephone to each other, nor ever could be, but two women caught by a web of sexual and psychological relationships in the front room of a council house.” (p 19)

This is the double bind of mothers, caught between fierce protection and competition, half passionate resistance, half surrender to the ways of men, a violence that breaks one filial relationship to begin another.

Here, in a darkened bedroom of 15th century Italy, it is hard to know which world the woman occupied, and impossible to know which one she wanted to occupy.

...

The chest measures 38 1/2 × 81 × 32 inches, which is not too far off the standard measurements of a coffin, a box bearing a woman into the conjugal bedroom, a story bearing a woman into the underworld.

...

Every woman a Persephone sequestered in an intimate Hades.

0 notes

Text

Clean and warm as a bone

As I write this, heavy rain is pounding the streets of Brooklyn. 6 months ago, I was in the desiccated, devastated landscape of rural Queensland. I went to an exhibition (cruelly) titled ‘Water’ and then to my father’s house near a town that had run out of water months earlier. The rain had disappeared, exposing the bottom of two dams, cracking in the sun.

In the exhibition there were works by Wukun Wanambi titled “Larrakitj,” hollow log memorial poles. Hollow log memorial poles are not actually hollow; they are spaces for the remnants of loved ones. I think about the British Museum, the climate-controlled warehouses where many such poles are stored. I think about what that could mean and I come up short, I can smell it but I can’t put it into words. Curators and sailors and looters and pirates came to this country and gathered these logs, shipped them back to a British basement, a congress of coffins. And they won’t give them back. Wukun Wanambi’s poles do not contain the remnants of loved ones; they are made for the museum, like a beautiful decoy.

Later, I walked with my father in Girraween national park, on Kambuwal land. I’ve walked this path with him throughout my life, but for the first time I encountered skeletons. The fires had run through in September and the tree’s bark had been blackened and slowly shed, curling back to reveal a pale core that glowed in the mid-afternoon light, clean and warm as a bone. I wanted to put my cheek against the surface.

I tried not to take pleasure in mourning. I tried not to turn these skinned trees into a marker of my grief, because in fact it’s too easy to call it grief. I can’t describe the feeling after the fires. The amount that has happened since then—a pandemic, a global uprising, curfews, helicopters. But it’s still there, a nameless devastation that I want, selfishly, to make my own. It’s as though I could hold it, and in so doing control it. But I can’t hold it, because I am held by it.

0 notes

Text

Every rape in the Met Museum #2: unholy alliances

Erastus Dow Palmer (American)

The White Captive

1857–58; carved 1858–59

The short text on the Met’s collection website describing this work is violently neutral; it informs us that “The White Captive portrays a young woman who has been abducted in her sleep (her nightgown hangs from the tree trunk) and held captive by American Indians.” She is an idealized victim, an embodiment of imperiled femininity—which is necessarily constructed as white. The title of this piece makes that explicit, but it is true of many other statues scattered throughout the museum. At the time of its exhibition this piece was commended for being a “thoroughly American” subject, “which consciously alluded to ongoing frontier skirmishes between Indians and white pioneers.” The name of the benefactor and patron of the artist, Hamilton Fish, the 16th governor of New York, is carved into the base of the statue.

This opalescent body was put on display as fodder for land grabs, an object which men on the frontier could hold in their minds as they passed out infected blankets, and which those in New York where the piece was displayed could hold up to valorize the work of colonization as some kind of white knighting moral purity. Her plump breasts coupled with the smooth, anatomically oblique groin of neoclassical statues, mark her as ‘womanly.’ But she has the face of a child. This infantilization doubles her frangibility. Bodies gendered female are made into comestibles for the gaze and at the same time, are deployed as ideological weapons in colonial and racist regimes. Rape has long been a violation aimed not at the women subject to it, but at the men to whom their bodies belonged.

However, this victimhood is not without its own perverse agency. White women have turned this vulnerability into political power. They have leveraged it to violent ends. This was made grotesquely clear in the recent video of a white women in central park calling the police on a black man, bluntly threatening his life with a calculated and frenzied performance of fear. She was not an outlier; we know that this happens every day somewhere in the United States. What does it mean that white women have gained power precisely by capitalizing on their (constructed) vulnerability to sexual violence? Trading on this vulnerability dehumanizes black and brown men, authorizing their murder.

Sitting in my local park a few days ago, in the middle of an uprising and a global pandemic that has women, including the most vulnerable among us--transwomen--confined to the domestic sphere in which so many are not safe, I looked down at the picnic table to see a note scrawled in sharpie:

The numbers are always going to be sketchy, since so much is at stake in domestic abuse for those who are abused: the very act of reporting can shatter support networks and leave people homeless. But the fact remains: family violence is two to four times higher in the law-enforcement community.

When the specter of sexual violence is mobilized to call in the police, we should always remember that not only are they statistically much more likely to kill a black man, they are statistically much more likely to be perpetrating violence against the women closest to them.

In Black Reconstruction, WEB Du Bois made the case that there was a racial bargain between working class whites and the plantocracy that prevented an alliance between the enslaved and poor whites, thus ensuring the supremacy of the plantocracy, and the coherence of the white race. Something very similar is at work in the alliance between white women and white men, which the authors of the Combahee River Collective called white women’s “negative solidarity as racial oppressors.”

It should not escape our attention that Bacon’s rebellion - that lost possibility of an alliance between poor whites and the enslaved, was set in motion by a shared desire to take the lands of the Powhatan nation. The ‘white captive’ that this sculpture depicts vilifies those whom the colonizing whites were displacing and attempting to eradicate from the earth. I don’t know what to do with this set of intersections, a set of deflections that can only end in violence.

I made a wearable sign the other day to take out into the streets. It says “White women: show up. Your silence will not protect you.”

I remain hopeful in this call. We can stop being white captives, and I mean captives not only to the threat of domestic abuse but also to our own desire for power formed in whiteness, and leave this negative solidarity, this unholy alliance behind.

0 notes

Text

Every Rape in the Met Museum

If you type the word ‘rape’ into the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection search, it will return some 183 results. This does not mean that you have located every depiction of a rape in the Met—how could you? For that you have to widen your search to include various euphemisms; abduction is a good place to start. (Nor does it mean that everything titled ‘rape’ is a violation of consent, as the Rape of the Locke attests.)

It’s really a few figures in the classics, famously raped and ravaged, whose violation lives on in hundreds of historical depictions: Europa, Proserpina, Arethusa, Ganymede. Mostly they are gendered female, but not all (Ganymede is a young boy). Each rape has been painted again and again, endlessly reprised by a culture both traumatized and titillated.

It's important to understand that Western art history has only recently placed a premium on originality. Throughout the periods we know as classical, baroque, neoclassical, mannerist, and so on, the goal was to display virtuosity. The painters painted the same scenes as their forebears, over and over. They drew on a fairly limited lexicon—biblical, mythological—which presented opportunities to show their master of line, light, composition, inventiveness (which is almost but not quite what we mean by originality). A facility with the brush, a malleable body bent to express just exactly what you want it to express. Delicious violation.

We no longer see classical rape scenes for what they are. This scene has become so normal that it barely warrants a mention; we no longer really see what the artworks depict. A lot of plot lines center on rape. A lot of dramatic tension is cultivated, deployed and released into our culture from these quiet moments in the museum. This nonchalance, this nonseeing, is also a species of violence.

What does it mean that for centuries, artists have reached for these few scenes, a tool in their kit, a body to endow with sympathy or sauciness, or to just be the shape around which fabric folds and falls?

...

If there is anything to be learned by reading all the museum’s extended labels for these works, it is that the museum and the whole discipline of art history understands this lexicon of violence as a means to display virtuosity and a mastery of materials. The Rape of Europa and Mercury and the Three Graces shown on the front face of a pocket watch provides an opportunity to talk about technique and technology; the sculptural Rape of Proserpina produced by the Doccia Porcelain Manufactory provides an opportunity to educate the public about the “challenge and reward” of overcoming the technical difficulties of porcelain—a relatively new technology at the time. Battista di Domenico Lorenzi’s depiction of Alpheus and Arethusa is a display of technical mastery and advances the “goal of Renaissance sculptors to depict figures in struggle and in movement.” The Abduction of the Sabine Women by Poussin likewise represents a “dramatic story [that] gave Poussin the opportunity to display his command of gesture and pose and his knowledge of ancient sculpture and architecture.”

The impending violence against a woman is necessary to their display of technical mastery. Just as the men in their images struggle to attain mastery over the women they are grabbing, holding, pinching, lifting from the ground, so the artists struggle to attain mastery of their materials. The dramatic structure, the moment to which they repeatedly return, is a tension that is cast as driving forward creative work, and the teleological development of man’s artistic endeavors.

...

John Berger says “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure.” A case in point: one painting in the Met museum by Greuze shows a woman reclining. She is not enjoying herself, she seems distressed, exposed to the elements. The wall label quotes the artist from the a letter to Diderot: "[I] should very much like to paint a woman totally nude without offending modesty." The story (such as it is) provides cover for the artist.

Berger goes on to write about the double gaze that women have internalized, and the ways in which their self-regard is constructed as frivolous vanity. There is something else that follows the same logic here, but a different category: women depicted as vain are typically in a state of repose. In classical scenes of rape, however, women are not in repose. Perhaps the story of a rape allows you to introduce movement into the canvas or the stone. You might enjoy the frisson of watching her struggle, endangered, and perhaps you also imagine yourself as her savior. Two things can happen at once in this dramatic scene. When Berger writes that a woman has internalized the male gaze and is always two, always seeing herself as you might, it also means that she is always looking at herself to imagine what might be said in a court of law: what were you wearing at the time? Even the cover of a prominent magazine recently showed a woman dress in black tights, black dress all buttoned up, low heels, accompanied by the line “This is what I was wearing 23 years ago when Donald Trump attacked me in a Berdorf Goodman dressing room.” In this way, too, women are watching themselves. They (we) are anticipating the gaze of the court, the judge, the community, waiting for the twitch of the tongue or the narrowing of the eye that says 'you-deserved-it'. I know why she said it. I know why they ran the story. His first line of defense was that she was not his type. The meaning just beneath the skin of the words: she was too ugly to rape.

It is common to think that Trump is uneducated and uncultured, as though an education would rid him of the desire to have mastery over women. But his desire for control and mastery is not out of place in the high culture; take a walk around the Met Museum.

...

There is also the politics of rape as a vector of virtue and violation, which is deployed particularly in discourses on race. The ‘imperiled’ femininity of white women has long been a catalyst for lynchings and for genocide. That DNA is in the museum too, continually reproducing itself through contact with the gaze. Classical scenes mark some bodies as vulnerable commodities, and others as nefarious threats. In Voyage of the Sable Venus, Robin Coste Lewis catalogues all the black women she can find in the museum, in fragments attached to furniture and in the backgrounds of paintings, “Everywhere I went, I found them, just off, just to the edge, just beneath: pieces of black female bodies buried in plain sight.” Each fragment is a story not told, a telling silence.

...

Over the coming days I will post a set of meditations on rapes found in the Met Museum, because this vast cultural cache has a lot to tell us about the contemporary politics of our bodies. I have included elements of the labels written by the museum in italicized text.

#metmuseum #rape #arthistory #classics #ovid

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fallen statues

You can take a tour through the streets of Bristol that highlights the residues of slavery. The tour begins on Guinee street, at the Ostrich Inn, a pub built in 1745 and a site where prominent slave traders would gather to make deals; trading humans and objects and currency. Behind the bar, a tongue-in-cheek says that unattended children will be sold into slavery—a stunningly dismissive marker of the gravity of this history. Across Pero’s bridge—named for an enslaved man who lived in the city—past The Old Bank on Corn Street, founded in 1750 by wealthy men, several of whom were deeply involved in the slave trade. From here you walk along Colston Street up to Colston Hall where the statue of Colston stands. This is the 5th stop on a 6-stop tour. But there are many more sites throughout the city. The man’s name is everywhere; on plaques and banks and streets and schools.

The felling of the statue was a vibrant movement, an eruption, a rupture, a pitching of bodies against cast bronze, against the man (one of many) who captured and enslaved ancestors, whose unjust enrichment attached itself to the future through street names and plaques. This was a symbolic performance, a moment of reckoning and reclaiming, a moment in which a young triumphal Black woman stood in the space they had opened atop the plinth.

The falling statue doesn’t get rid of yesterday. How could it? This city is threaded through the transatlantic slave trade. But the statue’s toppling does lay claim to tomorrow.

Audre Lord:

For all of us

this instant and this triumph

We were never meant to survive.

(A litany for survival, 1978)

They dumped him in the harbour. A fitting gesture; let’s not forget that countless people who had been kidnapped and were subsequently thrown overboard; in the infamous case of the Zong, the slavers did it to reap the insurance money, but in many cases it was simply because they did not want to expend resources keeping sick slaves alive. It is, then, entirely appropriate that Colston wound up in the harbor. The statue has now been retrieved, giving rise to questions of what will happen next. Lisa Lowe writes about the limits of archives as authorizing “knowledge about the history of slavery and freedom in terms of particular interests—those of slave owners and citizens, and not the enslaved—which denies enslaved people the humanity and presence it accords free liberal persons and society.” (Lisa Lowe, “History Hesitant.” 85)

Some suggested that it be displayed exactly as is, dented and spray painted, in a museum alongside commemorations of its removal.

(Image source: AP Photo/Kirsty Wigglesworth)

A chorus recommends that the space atop the plinth be used to feature contemporary commissions, particularly by artists of color. I have written elsewhere about the empty space atop these plinths, particularly in New Orleans. (I have also written about the removal of the statue of Marion Sims in Central Park)

(Image source: Bristol City Council tweet, June 8)

An aerial shot shows the empty plinth surrounded by handwritten protesting signs fanning out in all directions. M Shed in Bristol has collected the signs and will display them, alongside the statue. This will be an important, necessary display. But let’s not forget that the museum itself is a monument to slavery, a system arising from the technologies of colonization. Let’s not forget that Bristol itself is a monument to slavery, its streets an archive of bodies traded.

0 notes