Text

When you’re writing and can’t decide on a character’s appearance:

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

15+ Tactics for Writing Humor

A monster-length master list of over 15 tactics for writing humor, with examples from The Office, Trigun, Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Emperor’s New Groove, The Fault in Our Stars, Harry Potter, Pink Panther, The Series of Unfortunate Events, Elf, Enchanted, The Amazing Spider-man, and more. Be prepared to laugh.

(Please note that this article is best read on my off-Tumblr blog here so that you can watch the videos that go along with it, embedded into the post. Otherwise, enjoy reading it right here, with links to the videos.)

Introduction

I’ve been to a few workshops on writing humor, and I’ve read about writing humor, but the funny thing is, none of them really taught me how to actually write humor. But yet they all said the same thing: Writing humor is hard, harder than writing seriously, because if you fail at humor, you fail horribly.

I heard it so much, it made me fear failure rather than strive to develop that writing talent. For years I avoided writing humor, period. But the catch to that is that I also often hear how humor is a huge draw for an audience.

I read recently in Showing & Telling by Laurie Alberts that humor is hard to teach and that some writers believe it can’t be taught at all. If you know these writers, send them to this post, send them to this post, or send them to this post about why the concept that writing can’t be taught is bullcrap.

People think writing humor can’t be taught because they don’t know how to teach it. Some people can write humor, but can’t teach it. They don’t know how they are funny because it’s just intuitive and natural to them. I was at one workshop on humor, and the only “how-to” tip they gave was that humor had to just come up naturally in the story. But professional comedians slave away and work their butts off writing their jokes, and then practicing them. That’s not natural. Sure, some comedians do improv (Whose Line is it Anyway? was one of my favorite shows), so they’re more natural, but I believe most comedians have to work to be funny.

Look at shows like The Office. Those writers obviously know how to write that kind of humor. And they use some of the same humor techniques over and over–that’s not just happening, that’s planned out. It’s formulaic. Look at the Marvel movies. They have their own style of humor too. I once read an interview with Jeff Kinney, author of Diary of a Wimpy Kid, in it he talked about how insanely difficult it is to come up with jokes sometimes.

So yes, writing humor can be hard. But it’s not impossible. After all the (non)advice I got on writing humor. (Sure, some of them did mention one or two humor tactics, but not how to do them) I decided to take it into my own hands. So I’ve studied humor on my own, and I’ve made my own “How to Write Humor” article that actually tells you (or rather myself) HOW to write humor.

It’s not all-encompassing by any means. And I’m still learning. And note that you might have a different sense of humor than me, but you should be able to revamp most, if not all, of these tactics to suit you. Some of the tactics I will talk about today overlap each other, so one example might actually fit into several of these categories.

15 Humor Tactics

Overstatements and Exaggerations

An overstatement or exaggeration is playing up something–making something seem bigger than it is.

Humor articles I did read said exaggeration or overstatements are a no-no, and then go on by giving examples like “My room was so messy, it looked like a bomb had gone off.” Well, guess what? That’s just a bad example. It’s cliche. And just… blah. (I’ll explain why it doesn’t work in a second.) The articles are right, don’t write that one! But the articles are wrong in saying that there are no good exaggerations. That’s not true. There are loads of good exaggerations and overstatements. Most parodies and spoofs are exaggerations.

Keep reading

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Write a Novel: Tips For Visual Thinkers.

1. Plotting is your friend.

This is basically a must for all writers (or at least, it makes our job significantly easier/less time consuming/less likely to make us want to rip our hair out by the roots), but visual thinkers tend to be great at plotting. There’s something about a visible outline that can be inexplicably pleasing to us, and there are so many great ways to go about it. Here are a few examples:

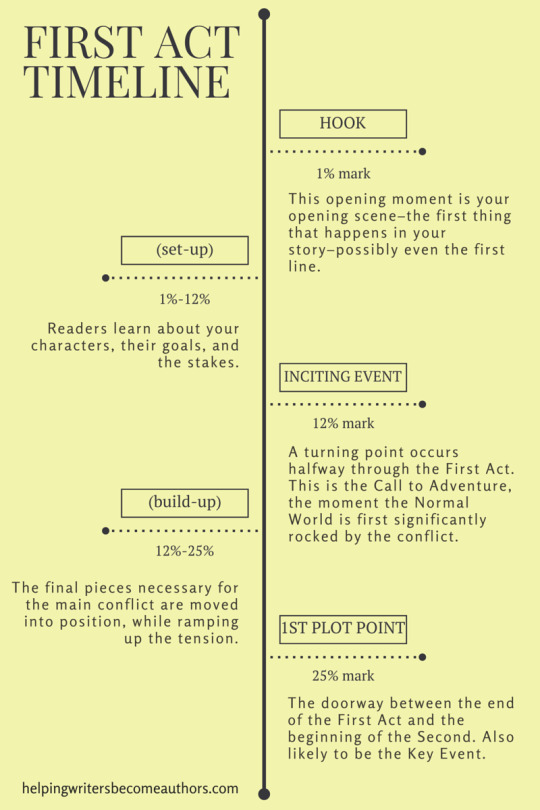

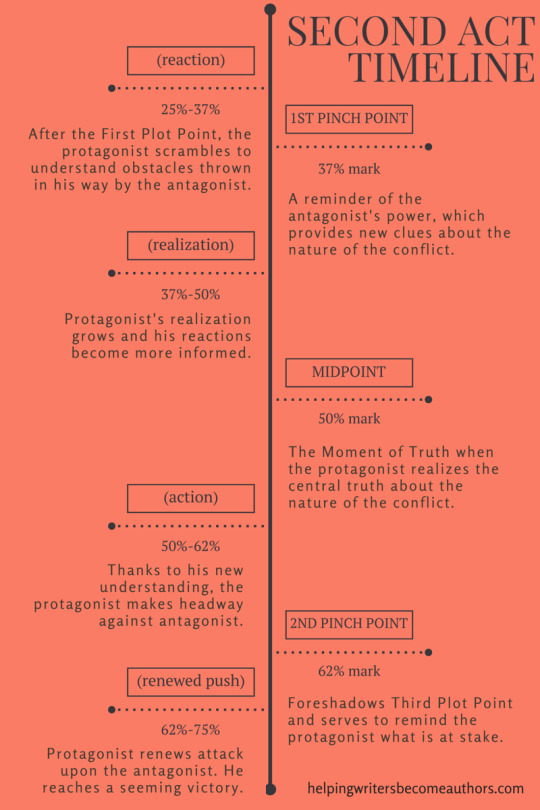

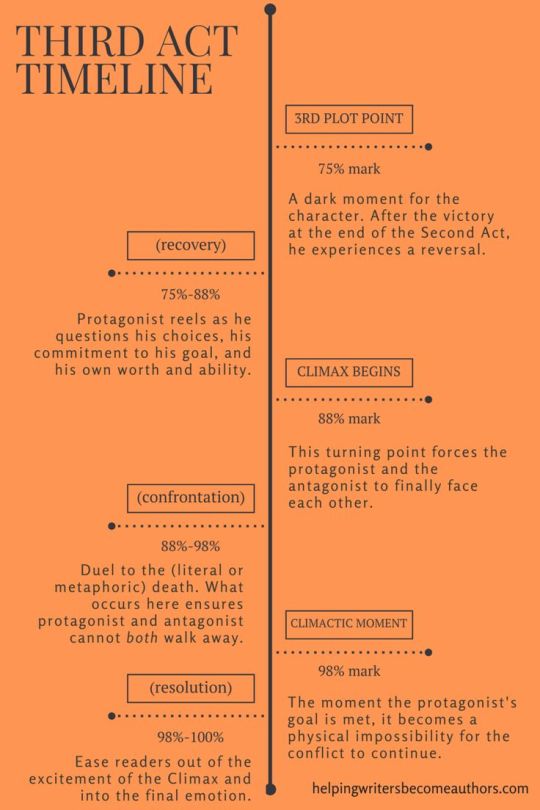

The Three-Act Structure

This one is one of the simplest: it’s divided into the tried-and-true three acts, or parts, a la William Shakespeare, and includes a basic synopsis of what happens in each. It’s simple, it’s familiar, it’s easy to add to, and it get’s the job done.

It starts with Act I – i.e. the set-up, or establishing the status quo – which is usually best if it’s the shortest act, as it tends to bore audiences quickly. This leads to Act II, typically the longest, which introduces the disruptor and shows how characters deal with it, and is sandwiched by Act III (the resolution.)

The Chapter-by-Chapter

This is the one I use the most. It allows you to elucidate on the goings on of your novel in greater detail than the quintessential three act synopsis generally could, fully mapping out your manuscript one chapter at a time. The descriptions can be as simple or as elaborate as you need them to be, and can be added to or edited throughout the progression of your novel.

Can easily be added to/combined with the three-act structure.

The Character Arc(s)

This isn’t one that I’ve used a lot, but it can be a lot of fun, particularly for voice-driven/literary works: instead on focusing on the events of the plot, this one centralizes predominantly around the arc of your main character/characters. As with its plot-driven predecessors, it can be in point-by-point/chapter-by-chapter format, and is a great way to map out character development.

The Tent Moments

By “tent moments,” I mean the moments that hold up the foundation (i.e. the plot) of the novel, in the way that poles and wires hold up a tent. This one builds off of the most prevalent moments of the novel – the one’s you’re righting the story around – and is great for writers that want to cut straight to the action. Write them out in bullet points, and plan the rest of the novel around them.

The Mind Map

This one’s a lot of fun, and as an artist, I should probably start to use it more. It allows you to plot out your novel the way you would a family tree, using doodles, illustrations, and symbols to your heart’s content. Here’s a link to how to create basic mind maps on YouTube.

2. “Show don’t tell” is probably your strong suit.

If you’re a visual thinker, your scenes are probably at least partially originally construed as movie scenes in your head. This can be a good thing, so long as you can harness a little of that mental cinematography and make your readers visualize the scenes the way you do.

A lot of published authors have a real big problem with giving laundry lists of character traits rather than allowing me to just see for myself. Maybe I’m spoiled by the admittedly copious amounts of fanfiction I indulge in, where the writer blissfully assumes that I know the characters already and let’s the personalities and visuals do the talking. Either way, the pervasive “telling” approach does get tedious.

Here’s a hypothetical example. Let’s say you wanted to describe a big, tough, scary guy, who your main character is afraid of. The “tell” approach might go something like this:

Tommy was walking along when he was approached by a big, tough, scary guy who looked sort of angry.

“Hey, kid,” said the guy. “Where are you going?”

“I’m going to a friend’s house,” Tommy replied.

I know, right? This is Boring with a capital ‘B.’

On the other hand, let’s check out the “show” approach:

The man lumbered towards Tommy, shaved head pink and glistening in the late afternoon sun. His beady eyes glinted predatorily beneath the thick, angry bushes of his brows.

“Hey, kid,” the man grunted, beefy arms folded over his pot belly. “Where are you going?”

“I’m going to a friend’s house,” Tommy replied, hoping the man didn’t know that he was ditching school.

See how much better that is? We don’t need to be told the man is big, tough, and scary looking because the narrative shows us, and draws the reader a lot more in the process.

This goes for scene building, too. For example:

Exhibit A:

Tyrone stepped out onto his balcony. It was a beautiful night.

Lame.

Exhibit B:

Tyrone stepped out onto his balcony, looking up at the inky abyss of the night sky, dotted with countless stars and illuminated by the buttery white glow of the full moon.

Much better.

3. But conversely, know when to tell.

A book without any atmosphere or vivid, transformative descriptors tends to be, by and large, a dry and boring hunk of paper. That said, know when you’re showing the reader a little too much.

Too many descriptors will make your book overflow with purple prose, and likely become a pretentious read that no one wants to bother with.

So when do you “tell” instead of “show?” Well, for starters, when you’re transitioning from one scene to the next.

For example:

As the second hand of the clock sluggishly ticked along, the sky ever-so-slowly transitioning from cerulean, to lilac, to peachy sunset. Finally, it became inky black, the moon rising above the horizon and stars appearing by the time Lakisha got home.

These kind of transitions should be generally pretty immemorable, so if yours look like this you may want to revise.

Day turned into evening by the time Lakisha got home.

See? It’s that simple.

Another example is redundant descriptions: if you show the fudge out of a character when he/she/they are first introduced and create an impression that sticks with the reader, you probably don’t have to do it again.

You can emphasize features that stand out about the character (i.e. Milo’s huge, owline eyes illuminated eerily in the dark) but the reader probably doesn’t need a laundry list of the character’s physical attributes every other sentence. Just call the character by name, and for God’s sake, stay away from epithets: the blond man. The taller woman. The angel. Just, no. If the reader is aware of the character’s name, just say it, or rework the sentence.

All that said, it is important to instill a good mental image of your characters right off the bat.

Which brings us to my next point…

4. Master the art of character descriptions.

Visual thinkers tend to have a difficult time with character descriptions, because most of the time, they tend to envision their characters as played their favorite actors, or as looking like characters from their favorite movies or TV shows.

That’s why you’ll occasionally see characters popping up who are described as looking like, say, Chris Evans.

It’s a personal pet peeve of mine, because A) what if the reader has never seen Chris Evans? Granted, they’d probably have to be living on Mars, but you get the picture: you don’t want your readers to have to Google the celebrity you’re thirsting after in order for them to envision your character. B) It’s just plain lazy, and C) virtually everyone will know that the reason you made this character look like Chris Evans is because you want to bang Chris Evans.

Not that that’s bad or anything, but is that really what you want to be remembered for?

Now, I’m not saying don’t envision your characters as famous attractive people – hell, that’s one of the paramount joys of being a writer. But so’s describing people! Describing characters is a lot of fun, draws in the reader, and really brings your character to life.

So what’s the solution? If you want your character to look like Chris Evans, describe Chris Evans.

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about:

Exhibit A:

The guy got out of the car to make sure Carlos was alright, and holy cow, he looked just like Dean Winchester!

No bueno. Besides the fact that I’m channeling the writing style of 50 Shades of Grey a little here, everyone who reads this is going to process that you’re basically writing Supernatural fanfiction. That, or they’ll have to Google who Dean Winchester is, which, again, is no good.

Exhibit B:

The guy got out of the car to make sure Carlos was alright, his short, caramel blond hair stirring in the chilly wind and a smattering of freckles across the bridge of his nose. His eyes were wide with concern, and as he approached, Carlos could see that they were gold-tinged, peridot green in the late afternoon sun.

Also note that I’m keeping the description a little vague here; I’m doing this for two reasons, the first of which being that, in general, you’re not going to want to describe your characters down to the last detail. Trust me. It’s boring, and your readers are much more likely to become enamored with a well-written personality than they are a vacant sex doll. Next, by keeping the description a little vague, I effectively manage to channel a Dean Winchester-esque character without literally writing about Dean Winchester.

Let’s try another example:

Exhibit A:

Charlotte’s boyfriend looked just like Idris Elba.

Exhibit B:

Charlotte’s boyfriend was a stunning man, eyes pensive pools of dark brown amber and a smile so perfect that it could make you think he was deliciously prejudiced in your favor. His skin was dark copper, textured black hair gray at the temples, and he filled out a suit like no other.

Okay, that one may have been because I just really wanted to describe Idris Elba, but you get the point: it’s more engaging for the reader to be able to imagine your character instead of mentally inserting some sexy fictional character or actor, however beloved they may be.

So don’t skimp on the descriptions!

5. Don’t be afraid to find inspiration in other media!

A lot of older people recommend ditching TV completely in order to improve creativity and become a better writer. Personally, if you’ll pardon my French, I think this is bombastic horseshit.

TV and cinema are artistic mediums the same way anything else is. Moreover, the sheer amount of fanart and fanfiction – some of which is legitimately better than most published content – is proof to me that you can derive inspiration from these mediums as much as anything else.

The trick is to watch media that inspires you. I’m not going to say “good media” because that, in and of itself, is subjective. I, for example, think Supernatural is a fucking masterpiece of intertextual postmodernism and amazing characterization, whereas someone else might think it’s a hot mess of campy special effects and rambling plotlines. Conversely, one of my best friends loves Twilight, both the movies and the books, which, I’m going to confess, I don’t get at all. But it doesn’t matter that it isn’t good to me so long as it’s good to her.

So watch what inspires you. Consume any whatever movies, books, and shows you’re enthusiastic about, figure out what you love most about them, and apply that to your writing. Chances are, readers will find your enthusiasm infectious.

As a disclaimer, this is not to say you get a free pass from reading: I’ve never met a good writer who didn’t read voraciously. If you’re concerned that you can’t fall in love with books the way you used to (which, sadly, is a common phenomenon) fear not: I grappled with that problem after I started college, and I’ll be posting an article shortly on how to fall back in love reading.

So in the meanwhile, be sure to follow my blog, and stay tuned for future content!

(This one goes out to my friend, beta reader, and fellow writer @megpieeee, who is a tremendous visual thinker and whose books will make amazing movies someday.)

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Endearing Characters - How To

Give them flaws - There is no-one on this world who is perfect, so there’s no need to shy away from giving your character negative traits. If your character has no negative traits they’ll be less believable for your reader, and neither will they be relatable, but they will be BORING. Trust me, your character will be less believable then a flying pig cleaning out your Mum’s kitchen if they have perfect personalities and endearing flaws. Don’t be scared to make them have dislikeable sides - every person in the world has them.

If you want to, give them mental disabilities - done well, they can add depth and realism to your character. Don’t give them paranoia because ‘it makes them better’, give them paranoia because it makes sense - research these things and you’ll find that these things make your character more 3D. This being said, remember, research, research, research: people with manic depression aren’t just ‘sad all the time’, depression is an actual illness and therefore has far more to it then just tears and upset. People with autism aren’t 'super good at maths but bad at english’, each person has a unique set of traits, way of speaking and interests.

Make them relatable: If your readers aren’t connecting with your character, that’s an issue. We can all relate characters like Harry Potter, not because we’ve lived his life or because we’ve been to Hogwarts ourselves, but because of how complex and well written his personality is. The struggles and emotions he feels we can all empathise with. I’m not saying write your character as a different Harry Potter - I’m just saying make sure that no matter how far from 'reality’ your character might be, make sure that the struggles they go through can be felt by the audience - even Killua, who has been through a far different life to most of us is relatable because he also feels and struggles just like we do.

Take time to consider what you want your character to be doing and what they represent, and don’t shy away from pouring emotion into their actions. As a reader, you want to be pulled into the action and therefore into their life - emotions are something we all feel and so we will connect with characters acting upon their own. Matching them, even subtly with those of your readers will make your character more relatable as a whole.

Have them be realistic: Not in the sense that they have to be realistic in our world, but in theirs. Their actions have to make sense in comparison to the occurrence. If their friend has been taken, think about it logically and then have them react. Even the most spontaneous of characters will think and react before doing something. If you’re finding this tough or constantly questioning if they make logical sense, you’re finding it hard to get into the characters head. No matter what, make sure you’re writing to the reader why so that we can understand their actions.

They should be a go-getter: This doesn’t mean that every single thing they do leads to happy conclusions or are done with good intentions, but a good character should always dosomething. Along with this, they should also be able to do a lot of this alone. Of course they will have friends and comrades with them, but any protagonist must overcome the main milestone themselves without any help from their friends. Any shonen protagonist would be a good example - Luffy always overcomes the main points alone and reacts, but often loses things he meant to protect.

This doesn’t mean you must have a super active character, unmotivated characters can still work as protagonists. However, there would be no real story if all your character did was sit alone and do nothing. Eventually, they will do something. At some point their motivation can fade again, but the main thing is that they have to change this sooner or later. Luffy would work as an example - he loses motivation at the end of the marineford arc, but eventually gets over this and continues with his training.

Balance them out: Every personality is going to have depth to it - think of it like one of those gobstoppers. The first layer shows them to be rude, but a little more delving shows them to be shy, or trying to be funny, or just someone who doesn’t see the point in manners. Balancing out all the positives and negatives is crucial in a character, and throwing in neutral traits, likes and dislikes, quirks and habits are equally important. They don’t have to make logical sense, for example a character who lies a lot could also dislike liars, but they do need to be realistic and therefore balanced as a whole.

- Happy writing !

Mod tabby

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

84K notes

·

View notes

Quote

Write. Write well. Write to the end. Take as long as you need.

Merilyn Simonds

(via writingdotcoffee)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

when your ocs start doing their own thing instead of sticking to the lovely and reasonable plot you’ve created for them

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

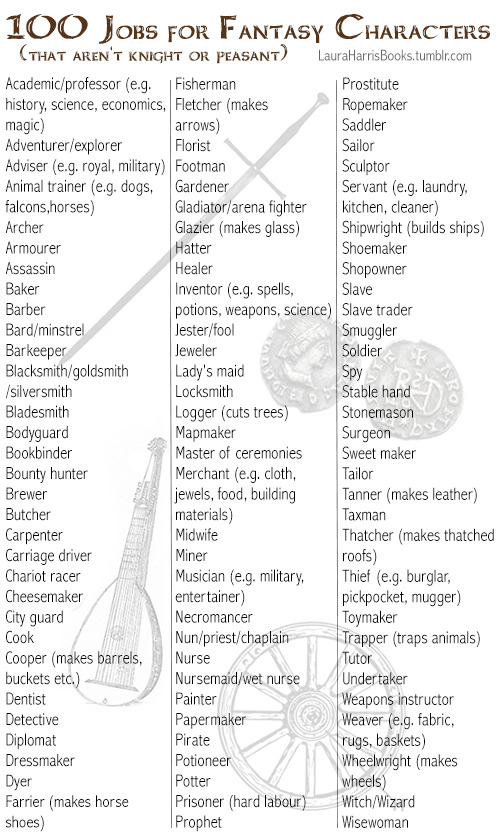

Beyond this, consider how these professions might vary depending on who the customers are - nobles, or lower class. Are they good at their job or just scraping by? Do they work with lots of other people or on their own? City or village?

For younger characters:

Apprentice to any of the above

Messenger/runner

Page/squire

Pickpocket

Shop assistant

Student

Looks after younger siblings

(Images all from Wikimedia Commons)

205K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Writing is actually such a lonely thing to do. Sometimes you spend hours and days just within your own head, without even realizing that you haven’t spoken to a living soul in ages. And from time to time it scares me how much I enjoy to do just that: Get away from everything by spending time with these people in my mind, in worlds I created, with ever purple skies and never fading summer nights.”

- // someone once asked me if people would get addicted to dreaming if it wasn’t a natural mechanism and I have found exactly that kind of drug in writing

j.d.m.

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

When you forget to describe the setting, so your characters are just doing their thing in a void

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to take criticism

It’s difficult innit. Sometimes when ya get those comments ya just wanna get those walls up and start defending. But I got this handy little trick I like to use when someone gives me criticism through text….

Do not read it with an angry voice!

When we first read those words;

“Hey maybe change this” or “think more about this thing” our sneaky minds can turn it into:

“Hey change this shit ya idiot” and “Have you put any thought into this at all???”.

Even things that aren’t really criticism can change if this angry voice takes over! A simple question like:

“I don’t understand this part…could you explain?”

can turn into:

“This shit makes no fckn sense”.

Our minds can be biches but that doesn’t mean we have to be! Thanks for coming to my tedtalk.

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daily #2,104! I can’t believe my novel would deceive like this.

304 notes

·

View notes

Note

I seem to only be able to write about my life and how I feel in my journal, I want to write stories but I don’t know how! The stuff I research seems so vague, any tips or resources?

I can’t give really targeted advice because this is a pretty broad question, but I’ll do my best.

As I see it, there are four main components to creating/writing fiction: creating a world, designing a plot, making characters, and telling a story through somebody else’s eyes. Now, those might seem intimidating, but most of them are both more common than you might think. If you’ve ever had a headcanon about the world of your favorite setting, you’ve done a small piece of creating a world. If you’ve ever told a lie, you’ve designed a plot. If you had an imaginary friend, you made a character. If you’ve ever explained or worked through someone else’s thinking, you’ve told a story through somebody else’s eyes.

Now, with writing stories, this tends to be a lot more in-depth and a lot more structured, but the basic underlying principle is really the same. To some degree it’s like strengthening a muscle; when you first start out, you may not be very good at it, but the more you work at it, the faster and easier it will come. That also means that it can be hard to jump straight from journaling to writing novels. There are a lot of writing prompts and writing exercises that you can find online, but here are some of my own suggestions:

For creating a world

Make up a place where you would want to go (a bookstore, a shopping mall, a skating rink, a cabin in the woods, a tavern full of vampires, etc.) Write down details about it–who goes there, what they do there, when it was made, who made it, who works there, whatever you personally would find interesting about that place. Now write down what’s around it. Is it surrounded by trees? In the middle of a city? Place it in the space it’s in, and write about that space, about whatever you think is relevant or interesting about that space. Now write about what surrounds that space. Is it in a country? On an island? On a spaceship? On the back of a turtle inside of a dome to keep toxic waste out? What’s around that space? Other countries? Other planets? Once you’ve gone out as far as you want to, go back to the original location and think about what you can add to that place now that you know about the space around it.

Come up with a holiday that isn’t celebrated right now. Figure out as many details as you can–who takes part, how, when? Then figure out why it’s celebrated. Who would celebrate a holiday like that? What would the world need to be like for that holiday to be celebrated? Does everybody celebrate that holiday within that world, or is it just a certain group? What do the other people celebrate?

For designing a plot

(This would be easier with a bunch of index cards.) Take a basic plot (boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy regains girl, etc.). It can be a plot you’ve read a thousand times; you can take it from your favorite story. But start with something super basic–no more than a sentence. For each part of that basic plot (eg. ”boy” “meets” and “girl”) write up a very basic idea of what you want to happen (boy is farmboy, girl is princess, they meet when she falls out a window, etc.). Lay them out in order. For each index card, use as many index cards as you need to expand on them: are there complications, are there failed attempts, are there other things involved? Lay them out in order. Does anything not work? Write a different index card for it. Does anything still need expanding? Write a new index card for it.

Take your favorite story and think of a place where things could have gone differently. Think about how they could have gone differently. Then think about what that would have affected. And what that would have affected. And so on. Pick an earlier point and change things from there.

For making characters

(This can also help with the next part) Start writing a journal from someone else’s point of you. You don’t need to know many details about them before you start writing; at first it should be more about what they feel. How did their day go? What happened? Do they want something? Do they hate something? What’s going on in their life? Try to do this for at least a few days, following the life of this other person, until you get a feel for the character. Then take something you described in one of the journal entries and write it out as a scene, told from an outside POV (either in 1st person of someone else or a 3rd person narrator). Think of what the character would look like, how they would act, and how their description of what happened would differ from what an outsider sees. From there you can write up more about the character–their background, their hobbies, all things you should be able to start to tell from the journal entries you started with.

Come up with an original character for your favorite book, movie, or series. They can be as simple as complicated as you want; just try to think about who you would want to see or who you think it would be cool to see in that story. Then try writing a scene or two with them in it. The scenes don’t need to be part of a larger plot if you don’t want; they can just be ficlets of the character interacting with the world or other characters that you’re already familiar with. Then try making another original character, either for the same story or another. Write a few scenes from them.

For telling a story through somebody else’s eyes

Write something from the point of view of an inanimate object.

Pick a character from your favorite work and write something from their point of view (a scene in the story, an implied scene, a reaction, etc.) Write some more things from their point of view, and try to stay as consistent both to their canon characterization and to your own internal style of writing them as you can.

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing is, 10% typing and 90% staring at your computer trying to find a better way to describe someone eating a piece of toast.

21K notes

·

View notes