Text

i wish all bisexuals a very lovely evening

#my art#komnena gecaj#florijan kovac#this is my spam account but on tumblr#on twitter its just the same but worse#anyways. bisexual people!#i just think they’re neat#liaisons

1 note

·

View note

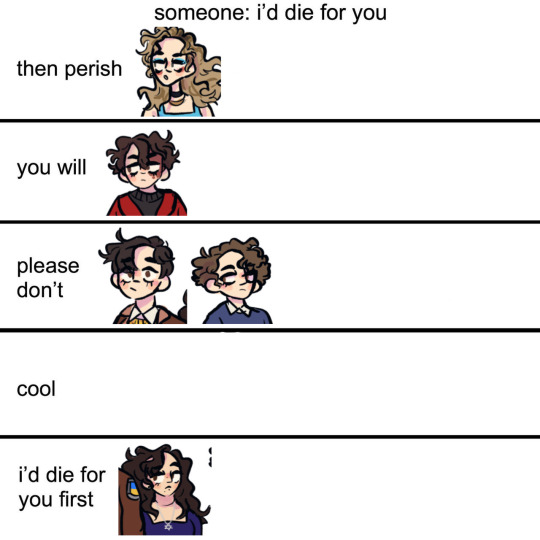

Text

now from the top make it drop

1 note

·

View note

Text

for everyone up at 11:30 pm this fine saturday have a lovely evening

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

what the hell. liaisons carrd?

#i spent 2 hours on this until carrd said no <3#didnt know there was a limit on things but go off carrd dot co#its ok though bc all of the juice is there#sad i cant make character bios but a loss i am taking#<3#just look at my toyhouse for bios#or ill add in links to everyones th later#we will SEE#anyway im out#you kids have fun looking at this unorganized as hell carrd#byeeeeee#she speaks

1 note

·

View note

Text

i finished a ukrainian sleepover (🎉🎉🎉) so have alignment charts with the cast

#fun fun fun#what will she write next vote now on ur phones#im planning a halloween fic and an among us fic#maybe#also an edgar and cordelia fic is in your future#for da shakespeare stans out there#🙈#shitposts#liaisons

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the ceos of “fucked up if true”

#thinking#me not focusing in aplang bc im on jstor😍#olek slobodyan#alla pivovarova#my art#liaisons#arghhhh#*sleeps

1 note

·

View note

Text

me looking up ‘donetsk’ and ‘luhansk’ on jstor:

research papers in spanish and norwegian:

1 note

·

View note

Text

the president has fallen in love with the president!

#*hurls my ipad across the room#this was a good 2 hours of doing absolute nothing but thinking#love love love them#go gay boys go#my art#cvetko rajkovic#mr. k#liaisons

1 note

·

View note

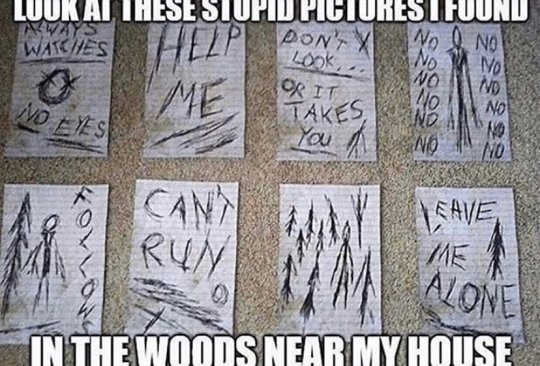

Text

whagt the hell nadia has a creepypasta oc???

its october mf

wc: 3.6k

not very well written and a bit of a hot mess but still love this tall king <3

There was this kid at my school.

There was a kid at my school, and I just really need to talk about him. I think it’s something I need to put out there. I am talking about it because anyone and everyone I talk to seems to never remember his name, or him in general, but I can’t stop thinking about his face.

I was never popular at school, and my brother always outshined me in that fact. He was a cheerleader, and I was his nerdy, unattractive sister. His friends were never friendly with me, and it wasn’t easy for me to make new ones, so I mostly kept to myself. Besides a few nice classmates, I was a bit of a loner, and this led me to Charlie.

Charlie Nguyen had always attended school in my city. I knew of him — we’d never actually talked, besides nearly 10 years of attending school together. Come to think of it, I don’t think anyone really talked to Charlie. He was always there, a lingering presence, and seemed to get on better with teachers than he did with other kids. Despite both of us being outcasts, we never interacted, right up until recently. He just tapped my shoulder in the hallway once, shyly staring at his feet and asking if I would like to eat lunch with him in the library. Despite his crooked posture and timidness, he towered over me. I was only as tall as his shoulder. I had nothing to lose from it, really — it was more preferable to spending lunch with Ernest and his friends, so I accepted cheerily which made him very happy.

Talking to him, I was shocked at how much I missed out on by never bothering to strike up a conversation. He was funny, sweet, and a hell of a lot more intelligent than I had believed. I’d often seen my teachers slip back 70s and 60s to him, but in one of the library’s secluded corners, we discussed politics and art and existentialism. I don’t even know how we got into talking about philosophy and what defines the self, but by the time the bell rang, my lunch was not eaten and I was much more enlightened than I was before. It was like a lightning bolt. I told him I’d be glad to eat lunch with him tomorrow as well, and he seemed very appreciative of it. As I headed to my last class, I realized I forgot to ask for his number, but decided I’d ask the next day.

Something about Charlie was just so alluring. I didn’t know much about him at all, even after our daily lunches began — he was 17, from Fresno, and his mother passed when he was young. Half-Vietnamese, half-white, and he spoke broken Spanish and loved to draw cartoons in the margins of his notes. I found myself chatting with him through text past my bedtime, where we’d discuss our lives, our academics, our interests. One thing Charlie and I really bonded over was our shared interest in both Shakespeare and horror movies. He’d been enamored since he read Romeo and Juliet his freshman year, but Hamlet was his favorite. At the time, I was peeling through AP Literature with straight A’s and was much more concerned with Tolstoy and Plath and Camus, but his fascination with the bard was certainly something I could bond with him over.

I prefer the comedies, though. Midsummer’s Night, Much Ado, As You Like It. Charlie’s interest in the tragedies ranged from the general to the obsessive, where he would produce sermons and sermons of how much the words and writings spoke to him. Considering how much death was in Hamlet and Macbeth, his other favorite, it concerned me, but I passed it off as nothing unique. After all, he was also a fan of slashers and all things horror. He loved a good scare. Whenever I tried to coax him into visiting his house for a movie night or a sleepover, he’d defer, and I would glumly accept the sentence. Once I switched the proposed setting from his house to mine, he gladly accepted.

Ernest was a little bit less enthusiastic about my liaisons with Charlie. They had gotten into scuffles before. Ernest got a very stern slap on the wrist for pulling on Charlie’s crutch in the hall once, freshman year. I told him a week in advance, just so he knew to vacate the house the next Friday and allow me and what he so lovingly called ‘the creepy asshole’ to watch a movie together. Ernie huffed and puffed about it the whole week and it really began to get on my nerves. The entire week, he bugged me and demanded just what I saw in that freak. I excused it as brotherly overprotection, but as Friday grew closer, I started to realize that it was fear.

When he dropped me off that morning, I confronted him in the car. “Why are you so scared of Charlie?”

Ernie scoffed. “I’m not scared of Charlie.”

“You sound pretty paranoid when you’re dropping a curfew on me and telling me to not get too close or talk too much.”

“Well, mom and dad are out of the house, and I wouldn’t want anything to happen to you.”

“Charlie is a freak. He’s... creepy. I can’t place my finger on what’s up with him. Esme, just tell me, have you ever left the room with a splitting headache when you’re with him? Has your phone ever started bugging out? Hm?”

I thought back. Well, a few lunches in, I did have such an awful headache I had to excuse myself from class to go try and throw my guts up in the bathroom. It wasn’t that, though, and it had subsided by the end of the school day. The back of my skull would sometimes pound and contract, but I didn’t think it was anything, reducing it to pollution or mold in the school. It always ebbed when I left the school. For my phone, it would get a little buggy. Just a little buggy, though! I had no reason to think it was Charlie’s fault! It’s not like we live in a world where that shit happens. He’s not some psychic, he’s a weird, lonely kid with trauma. That’s it. And I let Ernie know that by screaming an expletive and slamming the door on him, spending the rest of the school day with a headache tenfold worse than the one I had all those weeks ago. By lunchtime, my head was pounding so fiercely I almost slipped and fell down the stairs.

Charlie noticed, and asked what was wrong, a worried look on his face. I asked if we could postpone, and went on to talk about how awful my headache was. He seemed very disappointed about it but nodded and accepted with a smile. I felt so guilty about it, but it was quickly absolved, because when I walked out of the library with him I must have blacked out in the hallway. Charlie and one of the other teachers brought me to the nurse’s office, where my mother brought me home as I moaned in the backseat.

The rest of the afternoon was a blur. A literal blur behind my crowded vision and the blood rushing in my ears, but I do remember awaking in the darkness of my room at around 1:00 AM. The red light on my digital clock said so. I awoke to the sound of something like water boiling, or when a witch’s brew bubbles inside of a movie or cartoon. It was bubbling, dripping, wet — but when I pulled back my curtain, everything appeared dry. No rain, not even any clouds. The stars were quite clear, due to the fact that it was a new moon. Despite that lingering sound of bubbling and popping, I was able to fall back asleep. I don’t know how long I slept, but when I came downstairs the next morning, my parents (and an over-concerned Ernie) were adamant that I stay home all weekend. I accepted that the next two days would be filled with boring movie binges and cups of hot soup and tea, and I plopped back under the covers. My head began to pound every time I checked my phone. I noticed Charlie had sent me a few texts, but I didn’t have the heart nor the energy to check what he had said.

Sunday is when things actually began to get weird. The batteries in the remote for my TV had gone kaput, and I remembered that Ernie usually kept the same type in his desk for his old lamp. It was easier to walk across the hall to his room than down two flights of stairs into the basement. I knocked, and when there was no response, I entered. The lights were off. This was strange, because Ernie always loved to keep lights on. My parents constantly griped about seeing his outline in the window as late as 11, either from the strip LED lights that lined his room, the fairy lights, the candles, or the overhead light. I flipped the light switch and rubbed my eyes, as it was the most brightness I had seen in the past two days. Beginning to feel a tad nauseous, I took a seat at Ernie’s desk, trying to recall which drawer he kept his batteries in. As I searched, though, I noticed one drawer was shut from the inside, most likely from a heavyweight.

I should have just kept it shut. I shouldn’t have pressed. I should have gotten what I needed and left it alone, left my golden boy brother’s life completely alone. Then I could live knowing he didn’t have any dark secrets despite being a little bit of a bully and just a tad too standoffish. But, being the curious girl I was, I kept pushing until the drawer gave in.

Composition notebooks. The white smudges across the notebook covers had been filled in with dashes of pen, each one meticulously filled in. All five of the notebooks had this pattern. Blacked out, no name on the lines or any signage, otherwise normal in appearance. By that point, I should have known, but I kept going. I was once again shrouded in that same allure I felt around Charlie, the strange sense of being drawn in. When I opened the first notebook, I had to stop myself from making a sound. Every single page. Every single page in that notebook was filled with scratches in multicolored ballpoint pen, pleads and hypotheses and prayers. Drawings, maps, entries. The pages were thin from being worn down so deeply with the frantic pen marks, and many of the pages had been torn through from the intensity of the writing. My nausea grew and I began to feel my head pounding again. But I just couldn’t stop. Trying to process those frantic words written and dated and laden with tables and records and drawings was like trying to decipher hieroglyphics. Particularly, there was one symbol and one familiar figure that was retained throughout the notebook’s contents. An O with an X slashed through it. It reminded me of how I marked my bubbles on Scantrons, one line through, one line through, shade in the bubble. And the figure. The figure. A faceless man, a white oval of a face atop a suit and tie, and what looked to be tentacles pouring out from the sides.

I was snapped out of my trance by the sound of footsteps rising up the stairs. I dumped the notebooks back in my drawer, besides the fourth one, which I tucked in the back of my shorts and underneath my sweatshirt. Ernie looked at me weirdly as I exited his room, but I offered a weak smile and held up the pack of batteries. He nodded, and I disappeared back into my room.

It fascinated me, and it scared me. When the oncoming headache and nauesa had left, I scanned over all his words and entries, observing each of his drawings and sentences and deconstructing like a true AP student should know how to do. I always assumed Ernie was going to parties when I heard his window open and shut or when he warned me he wouldn’t be home until late, not investigating supernatural entities in our affluent suburban town and measuring sound waves through apps he’d downloaded onto his phone. I hadn’t known Ernie was this brilliant. It took me about two hours of reading and rereading that singular notebook until I had connected the dots.

A few years ago, our cousin Ronnie disappeared. Ronnie and Ernie were best friends, close like brothers, and were inseparable at each and every family gathering. What I knew for certain about Ronnie is that he also had a particular fascination with ghost-hunting. He went out on frequent escapades with his girlfriend and her brother with some handy professional equipment in the most ‘supernatural’ bits of California. Most of my family excused it as a strange hobby that didn’t subtract from Ronnie’s successful business career, not until all three of the ghost-hunting squad disappeared without a trace while investigating the Lassen National Forest. No DNA, no bodies, no signs or directions or a reason were ever found. Even their car and all their expensive equipment, all of Ronnie’s research, had vanished into thin air. It seemed he had become one of those ghost stories he so adored to pursue. It didn’t hit me that hard, as I hadn’t known Ronnie all that well, but I hadn’t factored in how much of Ernie’s personality had changed since the disappearance. He had become more standoffish with his rivals, more competitive with his athletics, more jumpy and paranoid.

I should have known by the way he looked at Charlie. I assumed it was drama I had missed out on or the pure perils of high school hierarchies. But I had never noticed how hateful, how accusatory it really was. For some reason, I was certain that Ernie had it in his head that all of these things were connected. The Faceless Man, the disappearance of our beloved Ronnie Halaifinoua, and the outcast at my school who was seemingly responsible for bugged out phones and splitting headaches. It made no sense, but at the same time, it was like a missing piece to a puzzle that I simply had to snap into place. I hid the notebook in my schoolbag, and went back on Monday armed with a bottle of aspirin and comfortable clothes, ready to confront Charlie.

At lunch, I took two aspirin and handed him the notebook wordlessly. We sat in silence as he slowly peered over the pages, absorbing the information behind blank eyes without a single sound. When he reached the final page, he set it down and asked, “Did you write this?”

“Ernie did.”

Charlie sniggered at that and crossed his legs. “Well, he’s onto me, now, isn’t he?”

I stared at him, slack-jawed, feeling duped. “You’re— you’re—“

“What, supernatural? I’d like to think so,” he gave me a mellow look. “Ah… you may want to take another aspirin. Watch this.”

I popped one and I watched. He closed his eyes and snapped his fingers. The lights above us flickered off, then on, then off again, before the lights reignited. Charlie opened his eyes, suddenly breathless, and nodded. “I can’t… usually do it with that much control. It needs work.”

I slammed my hands down on the notebook, my mind barreling at 100 miles per hour with a smattering of questions in tow. “Everything. Tell me everything. Now.”

Charlie folded his hands and gestured to the aspirin. I shook my head and pulled the bottle to my side. He cleared his throat, steadied his gaze, and began. “I wouldn’t call myself willingly supernatural by any means. I did not ask to be this way. I have been tossed through more foster homes in 17 years than I can count on my hands, and I would give anything to give up this life. I hate living a life where I’m unable to control my abilities. I don’t want to hurt others, I don’t want to do this, but sometimes it gets out of hand. Lucky for you,” he said. “Some people will gain immunity once exposed to it long enough.”

“Gain immunity to what?”

“It has a lot of names depending on the universe you’re in. They mostly call it the slender sickness, but you can call it the static sickness, faceless-man-itis, whatever. You do you. Headaches, nausea, hallucinations. Malfunctioning electricity. Static. The whole thing.”

“So it is you.”

“Always has been. Well, not totally. Faceless Man? The Faceless Man, as your brother says, he may or may not have touched my mother with his hand, therefore touching me as well and handing me a degree of abilities that I drag with me. It’s my cross, Esme. I’ve been avoiding his gaze for the past 16 years and have always managed to just be out of his reach, but my powers are getting stronger and it’s all getting more and more out of hand. I needed to go to someone.”

“Does he have a name? An actual one.”

“Many names. The Operator, the Business Man, Chernobog. Apparently, now, the Faceless Man. And I guess he’s my parental figure now. I’ve been chilling with him more often. Crazy dude, gotta say,” Charlie said, putting his hands behind his head and crossing his legs. “Crazy, crazy things.”

I looked at my hands, unsure of what to feel. “Did he kill my cousin?”

Charlie’s face went slack. “He’s killed many, many, people, but I don’t have control over what he does.”

We sat in silence for a long moment until Charlie spoke again. “I’m sorry for your loss.”

My heart began to pound. “Ernie’s after you,” I said, running a hand through my hair and letting it fall over my face. “I think he might try and hurt you.”

“So… movie night is postponed indefinitely, then,” he replied.

I grinned sadly at him. “Don’t make me laugh, this is serious. I don’t want you to be harmed.”

His arms dropped to his side, and he smiled at me. He smiled in a way that drew me back in all over again. “Esme, be here tomorrow. I’ll see you then.”

He vanished back out into the hall. I chose not to follow him. But, for the first time, I had a surprising lack of a headache, and I don’t think it was because of the aspirin.

That night, I slipped the notebook back into Ernie’s drawer. I think he may have figured it out, though, because when we bumped into each other on the stairs, we stared at each other for a good minute saying nothing. I believe it was my way of telling him which side I was on, because when he surrendered his gaze he slammed the door shut behind him and I heard rummaging in his room. I walked to school the next morning.

When I came to lunch the next day, Charlie was already waiting for me. He handed me a gift bag. “It’s a present,” he said. “For you.”

“What’s the occasion?”

“I’m moving. You might never see me again.”

“Oh, Charlie…”

“I say might. Might. There’s a chance we will meet again. Perhaps in another lifetime or in another universe. We can figure it out, alright? Alright.”

I shared my lunch with him, half a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, and we toasted to his new life with our milk cartons. When we left the library that day, our pinkies were interlocked. As he turned to go to class, I pulled him back, and kissed him on the cheek. “I’ll miss you,” I said.

He hugged me. It was like hugging one of those plasma balls where your hair stands up when you touch it. I had just stuck my fingers in a socket, but when I pulled back, all I could see were Charlie’s grateful, glowing eyes. “I’ll miss you too. Goodbye, Esme. Goodbye.”

My hair on my arms was still standing up and my cheeks were dark with color. I had a mark on my pinkie from where it touched his.

Since that day, I haven’t seen Charlie Nguyen. Ernie is still doing tests and taking entries though they become more inconsistent and confusing each and every day. I have an idea of who’s altering his readings. The present Charlie gave me, though, might hold some importance for me in the future. It’s a key without something to unlock, a piece of quartz, his copy of Shakespeare’s Hamlet with all his annotations in the margins, and a pair of earrings with ghosts on them. Quartz conducts electricity. I remember learning that in class. I always keep it in my pocket now. When I ask my teachers about him, they seem confused, as do the other students. Ernie and I have seemed to make a silent pact as to not discuss the matters of the supernatural. I think he’s looking for Charlie. He’s looking for anything that will bring him closer to the truth.

I feel farther to the truth than ever before, but I know I cannot be far from it. It’s a matter of time. Ernie has begun to have headaches lately.

#AHGH charlie love u#i started writing this like 2 months ago and finished it on a whim last night#im trying to write as much as possible while im on this literary induced high#we will see#anyway enjoy charlie lore#my writes#charlie nguyen#creepypasta

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

argh... assorted oc-tober things

#my computer still fucking dead god bless 💕#when my shakespeare hyperfixation isnt dormant anymore#you will all be sorry#SOON...#laszlo mincef#arpad valentine#marika semjonov#gustava nielsen#jelka horvatic#my art#liaisons

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

fashion 😎

1 note

·

View note

Text

more of them

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i drew it in july why is it still relevant

#good for them good for them#mr. k#florijan kovac#adriano belosevic#ben hunter#my art#??#why not#shitposts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

everything’s fractal

wc: 1.7k

okay this is a follow up to the fic i posted yesterday because these are the only two men i have brain worms for and i also need to keep writing every day or else i lose. anyways. hold hands or whatever

“I read your book,” Florijan declared. “It gave me a nightmare.”

Laszlo spun around, eyes wide as his gaze met Florijan’s. “Hello to you too, dear. Why did it give you a nightmare?”

Florijan shrugged, plucking it from his coat pocket and handing it back to Laszlo. “It was scary. I think you should return it to the library.”

“Uh, alright.” Laszlo stared at the cover. A Full History of Yugoslavia — Tito and Onwards. Debating, he shoved it in the bag tossed on his wheelchair, and started leading himself from the conference room. “Did it give you some context, at the very least? What made it... scary? I don’t think I understand.”

Florijan followed, his hands shoved in the pockets of his long gray jacket, ruined threads and tears running throughout it. “It gave me context... I don’t like the context. I don’t understand the brutality of it,” he said. “And I don’t like how we didn’t have a say in anything. And I didn’t like all the death and destruction and suffering. It didn’t have to be that way.”

“It, uh, it sure didn’t,” Laszlo muttered. He had begun to wonder if Slovenia’s newest president had even the faintest clue of the region’s own history. His face flushed an event of red, and he paused outside. “Let’s sit and talk. That works?”

Florijan nodded, his lips a thin line. “That certainly works, Laszlo.”

Laszlo patted the bench beside him and leaned forward as Florijan sat. From the morbid expression on Florijan’s face and the scrunched eyebrows on his, he almost began to feel like a parent giving a child a hapless explanation for a death in the family. The death being whatever history of Yugoslavia Florijan had believed before. “You seem bothered.”

“Learning about history makes me sad. I don’t like it.”

“You’re a man with a lot of empathy. There’s nothing wrong about that,” Laszlo replied.

Florijan huffed, his gangly hands folded into a neat bundle. “I feel duped. I feel duped that there was all this stuff I didn’t know. And I just lived my life without realizing any of it. I knew about the war. I knew there was a lot of people killed in it and that ever since then we’ve been seven instead of one. But all of those photographs, and the articles, and, and, and, the brutality of all of it. And we weren’t even fighting by our own means,” he mused, his voice trembling as he spoke. “Oh, Laszlo, it’s very sad.” Laszlo looked up when he felt Florijan’s gaze transfixed on him. “I see what you meant now. When you said what a troublemaker you are. But, but, you’re not. You’re a very good man with a big heart. Just because Macedonia has a bad rap doesn’t mean you should.”

Laszlo’s mouth twitched into a small smile before he looked away. “We shouldn’t have a bad rap at all.”

“I know,” Florijan said, putting his hand on top of Laszlo’s. “I know now. Izet always made these jokes that I could never understand, these vile jokes about you and Miss Arsic and Miss Horvatic. It makes sense now, it does, but I should have thought, oh... I don’t understand.”

Laszlo shifted. His hand was an icebox beneath the warmth of Florijan’s. “What don’t you understand?”

“The book... well. I did research, and it says— it says Slovenia isn’t considered a Balkan country. And Izet mentioned that sometimes, but I never really understood it, I just thought it was a consistent error he liked to make. Is it true, Laszlo? I don’t want it to be true. I think you guys are great. And I don’t fit in with Lorenzo and Manon and Aurelia— I mean, they’re great, but I do feel like the odd one out. I can’t speak German or French and they can't speak a word of Slovene or even read Cyrillic. It’s... weird. I always thought it was the other way around.” Florijan’s voice went increasingly distraught, and Laszlo’s panic flared in his chest.

“Don’t get upset. It’s okay. Um, let me explain it to you this way. You guys, the Slovenians, drink wine and beer. Me, Jelka, Svetlana, Agim, we drink rakija. Uhhh... that’s how I’ve heard it explained.”

“I don’t drink, Laszlo, I hate drinking! It doesn’t make sense,” Florijan let out a whimper of frustration and inhaled. “I apologize. This is making me rather emotional. Can you just— hm. Explain it to me like you would anybody else, and I’ll try not to get upset.”

“Don’t apologize. It’s fine. Promise. Erm,” Laszlo felt the back of his neck and his eyes touched the ceiling. He squinted through the glass panelling at the fractured afternoon sun. “Okay. It’s like, a stereotype, really, that you guys are more poised. You’re better. Less boisterous. You don’t fight or argue or make mountains from molehills. You handle things like those posh westerners do.” Laszlo steadied his gaze, and chuckled to himself. “You’re seen as one of the good ones. Too rich, too lavish, too educated to be grouped in with us,” he continued, dripping with venom. “But, Florijan,” his voice shifted back into a soft explanation. “I know you don’t think that way. Izet might have. Hell, the rest of the world might, but you don’t have to. You have the ability to decide what opinions you have, and that’s what’s so beautiful about history. Yes, it’s scary and depressing and leaves you feeling desolate and morbid but it gives you perspective. Needed perspective. So, uh, don’t lose sleep over it, alright? Just... make the right choice.” Laszlo straightened in his chair, as if he were defending himself at one of the various sessions or meetings with his cabinet or with the throng of fellow leaders. “Make your own choice.”

Florijan had never realized the sound of his own voice. He’d always thought his accent sounded different than that of the other Slavs who came to visit Izet, their tones and pronunciation being more defined, more proper, less casual. Everything was conducted with an air of dignity, a twill of formality sprinkled on posture and manners. He hadn’t known it was a unique thing until it all came into perspective. He also hadn’t noticed before how when Laszlo spoke at the meetings, his Slavic accent seemed to melt away in favor of what sounded like a mock British thing. When Laszlo spoke at those meetings, the uncharacteristic severity of his adoptive accent was dour and exuding with bitterness and icy etiquette. The way Laszlo spoke now, though, and the way he spoke at the library, was comfortable, relaxed, his voice soothing and not characterized by the harsh intonations of a western disguise. His accent was beautiful, it was colorful and chaotic but also fun and fitting all at once. It was uniquely Laszlo.

Florijan didn’t want him to hide the person he was beneath all those layers. He found himself first outstretching a hand, wordlessly, which Laszlo took, eyebrows furrowed. Then, with his emotion pouring out like an opened set of floodgates, he reached out both his arms and enveloped Laszlo in a hug. Florijan squeezed, careful to not hurt his friend, and rested his head in the corner of Laszlo’s neck, his eyes shut tight. Laszlo froze for a moment, stunned and caught like a red-handed criminal, and hugged back. Just slightly. His hands shook as he patted Florijan’s back and listened to the sound of his aggressive heartbeat. It was Florijan who let go first, folding like a house of cards and keeping his movements light and gentle. When Laszlo looked up, he realized Florijan’s eyes were welling up. “I don’t want you to hide from yourself just because the world said so!” Florijan whimpered, wiping his tears away with his sleeve.

Laszlo had never been so aware of the sound of his own heartbeat in his chest. It was so strong and filled his ears with that drumbeat of blood and life. He shut his eyes, choking back a tidal wave of emotion and hearing the pounding inside of his head. Like a swimmer coming up for air, he took in a long breath and turned back to a brimming Florijan, smiling like a politician. “Ah, thank you, dear. It means a lot to me that you say that. Thank you. Really, thank you.”

“Oh, Laszlo, you’re such a good man. You were so good today. You’re so clever and intelligent and wonderful, I don’t see why you have to hide behind— I don’t see why you should hide at all.” Florijan sniffled, making paws with his sweater and rocking back and forth in his place. “I look up to you.”

Laszlo felt that pit in his stomach again and his mouth grew dry. He sat there, a rubberneck to his own wreck, slack-jawed and wide-eyed. “Awh, shit, dear. I look up to you too. You’re an admirable fellow. I’m happy to be here with you. You’re doing amazing.”

Florijan swallowed the lump in his throat and nodded, blinking away the last of his tears. He grabbed Laszlo’s hands again, giving them a tight squeeze. Laszlo gazed at Florijan’s olive green nail polish. “That’s— that’s my favorite color, some fun Mincef trivia.”

Holding up his hand to study his own nails and then gaze back at Laszlo, Florijan beamed. “Green is beautiful! It’s the color of life.”

Laszlo nodded, his mouth a faint smile. “Yeah, yeah. You feel better now?”

Florijan nodded his head. “Thank you for talking with me… dear.”

“Noooooo problem, dear!” Laszlo responded, aiming finger guns and shooting with two snaps of his fingers. “Always a pleasure to see you around. I hope we can see each other more often.” To be fair, Laszlo thought, relations had especially stalled with Izet in power. Maybe it was time to repair that.

“Mmph,” Florijan replied, his head bobbing up and down. He kissed Laszlo’s outstretched hand and got to his feet, placing one of his firm hands on Laszlo’s shoulder. “I’ll see you around.” His words were smiling almost as wide as he was.

“See ‘ya.” Laszlo gave a salute.

Florijan saluted back, giggling as he disappeared towards the dorms.

Laszlo heard his heart pounding again.

#ah#men#they exist#these ones though <3#sobs#we are on laszlo/florijan lockdown#what s the ship name vote on your phones#call that#macevlenia#?#sorry that is awful#i will leave#laszlo mincef#florijan kovac#my writes#writeblr#liaisons#go crazy#lemme put this on ao3 for the heck of it too

1 note

·

View note

Text

ive been making these all evening now its my new hobby

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh yeah. i guess i can say this while my computer is still in the fucking shop but i am making an edmund king lear pmv??? amv??? lyric thing?????? and hopefully i will have my computer back by the time i finish it 💕

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ladies one at a time

#writing that fic in two sittings best decision i ever made#.........#i wuv them#ocs of the week bay be#florijan kovac#laszlo mincef#my art

2 notes

·

View notes