Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The purported ability of mission analysts to predict the impact points of reentry bodies that came down far from planned recovery zones was highly regarded, notwithstanding a consistent lack of success over several years in efforts to locate a variety of misplaced reentry items. [In one case] pieces of a Gambit vehicle purported to have come down in central Africa were found on a farmland in southern England.

- A History of Satellite Reconnaissance Volume I, by Robert Perry for The National Reconnaissance Office (1964-1973, declassified 2012)

0 notes

Text

Minuteman Launch Facility Demolition

[When dismantling a Minuteman Launch Facility] a decision was made to simply bury the launcher closure door as it was not thick enough to properly contain the explosive energies required to fracture the door without launching the debris beyond the fence into private property, which was not allowed by contract.

Emphasis added.

Source: Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare by David K. Sumpf (2021).

0 notes

Text

Rod Serling At The Beginning of The Twilight Zone

You're going to be, obviously, working so hard on The Twilight Zone that [...] for the foreseeable future, you've given up on writing anything important for television

- Mike Wallace to Rod Serling on The Mike Wallace Interview, 1959

With 3 Emmys, Rod Serling was already a distinguished television writer when he launched The Twilight Zone, and known for dramatic teleplays with strong moral and social messages. He was recognized for fighting for the writer's independence as an artist - one biography called him "TV's last angry man". Starting The Twilight Zone was seen as essentially "giving up" on making serious television, and sinking to "mere" entertainment (though, he insists, of a high quality), primarily avoid the censorship he fought against for so many years.

In this fascinating (and AFAIK, unique) interview just before the start of The Twilight Zone, he explains why he made this change, what he saw as The Twilight Zone's role, and is refreshingly candid about both his own philosophies and insecurities. Surprisingly, he didn't foresee (or didn't admit out of fear of censorship) that The Twilight Zone would not only espouse the same messages he was already known for, but in a profoundly effective way.

Today, of course, The Twilight Zone had such a pronounced influence, he known for little else, even though he wrote or co-wrote still-popular works such as Seven Days in May (1964) and Planet of the Apes (1968).

The interview can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ydXkZ_hDztc.

0 notes

Text

Getting Set in One's Ways (Part 2)

Last time we saw a relatively benign example of a machinist preferring his tried-and-true techniques to new ones. This next example is a little more - ah - shall we say insistent.

A friend of mine was demonstrating [gauge blocks] to the owner of an antiquated little macine shop, nestled somewhere in the foothills of the Alleghanies [sic] [...].

"Some of those newfangled measuring blocks, he?", he cackled, fingering the precision-smooth steel rectangles. "These young shipjacks are always thinkin' up some span-new gimmick to complicated things with. Ain't nothing on the market today can take the place of a sharp eye and a steady hand, young feller. I been making tools for over forty-three years and I know what I'm talkin' about". [...] "Give us that 1/2-inch block here and I'll show this city feller something. Think these gimcracks [sic] here are accurate, eh? Wait I'll I show you."

From the pocket of his overalls he pulled out a battered micrometer caliper. "Always carry Betsy around with me, " he grinned, "so's I can check things right on the spot." [...] "Four point nine---what did I tell you, young feller? Four point nine nine six---knew it all the time! Four point nine nine six and a wee bit! What did I tell you? This here gewgaw [sic] is off a good four-thousandths of an inch! Precision blocks! What kind of precision do you call that, eh? I coulda told you they were out to cheat the public with those doodads!"

My friend suggested that the discrepancy might possibly be due to the caliper.

"Look here, son," the old toolmaker said, "I've been using this mike since I was a journeyman apprentice back in [1861], long before you were born, and I've never had any trouble with it from that day to this. Take your little toy blocks back to Mr. Johansson and tell him we don't need any knicknacks like them around in a first-class shop. We're doing all right as we are. Furthermore, you can tell that Swede from me that he better get himself a new pair of glasses! Tell him I said so!"

Excerpt from 60 Years With Men and Machines by Fred H. Colvin (1947).

0 notes

Text

Getting Set in One's Ways (Part 1)

As I grow older, I find myself less and less enthusiastic about new technologies, and more resistant to changing how I work. Of course, this tendency has always been common, perhaps even more sow among technologists than the general population because we see how the sausage gets made.

In his memoir, Fred Colvin describes (among other things) observing the techniques of machinists from all over the US, including those a little set in their ways:

Some of the old mechanics, for example, had no use at all for the newfangled taps and dies that began to appear near the close of the past century [19th]. One skilled toolmaker in Greenfield, whom I knew slightly, believed they were nothing but a bother, and preferred a tap made from a piece of square steel with teeth cut out on the corners, which he claimed eliminated the need for fluting or squaring the shank. His favorite die was made by annealing an old, worn-out file, drilled and tapped in the center, with four small holes outside the thread drilled and filed into the tapped hole. This, he said, gave the necessary cutting edge and cheap clearance, as well as the diestock, all in the same piece.

Excerpt from 60 Years With Men and Machines by Fred H. Colvin (1947).

0 notes

Text

Minuteman Backup Communications

Nuclear war has the potential to disrupt communications (citation needed). Raising the transmission point typically helps extend the range of the VHF and HF radios used to communicate with Minuteman Launch Facilities. So the Air Force did that. They raised it high.

In fact, they put the transmitter on a rocket, and when they needed to send a message they, launched the transmitter in to space, well in to LEO altitudes (albeit on a suborbital trajectory). In this Emergency Rocket Communications System (ERCS), modified Blue Scout Junior boosters contained a prerecorded messaged, and the system was operational between 1963 and 1967, when it was made obsolete by Minuteman II.

Wait, I should rephrase that. The Blue Scout Junior rockets were replaced by Minuteman II missiles. The plan was to launch an ICBM to send each message.

The missiles were barely modified, with most of the new equipment being a drop-in replacement for a warhead. The same concept of retransmitting a prerecorded message was used. Minuteman II-based ERCS remained active until 1991 when MILSTAR satellites could provide the same capabilities.

Source: Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare by David K. Sumpf (2021).

0 notes

Text

| > i hope we are not getting into the waters entered by algol68, in | > which it was said that the correct interpretation depended on | > being able to distinguish, when reading the standard, between a | > roman and an italic comma. | | don't worry. the text of the standard that describes | nonadvancing i/o is so unclear that commas make no | difference, much less the fonts of commas.

Source: https://yarchive.net/comp/fortran_standard.html

0 notes

Text

Whitespace-Insensitive

This is a fun one, but its going to need a little bit of background first.

Aside 1: Word Demarcation

Using spaces to demarcate words is a surprisingly recent innovation. Written Classical Latin and Greek both employed a form called scripto continua, in which words run one in to one another. This would look something like

Thiswouldlooksomethinglike

Occasionally, an interpunct (·) would be used to separate words, particularly on monuments and inscriptions, but it was not an obligatory part of the orthography. Separating words with spaces appeared in the seventh and eights centuries, and spread over the next few hundred years.

(All [0])

Aside 2: FORTRAN Whitespace Handling

Not only is FORTRAN whitespace-insensitive in the modern sense of collapsing all whitespace into a single character, whitespace was completely ignored, even within a keyword or variable name.

For example, GO TO and GOTO are completely equivalent, and would presumably be tokenized the same.

(All [1])

Finally

These facts led one FORTRAN manual to quip

Consistently separating words by spaces became a general custom about the tenth century A.D., and lasted until about 1957, when FORTRAN 77 abandoned the practice. [1]

[0] Wiki will do here

[1] SunSoft FORTRAN77 4.0 User's Guide, 1995.

0 notes

Text

Early Scheduling

In 1959, Christopher Strachey wrote "Time sharing in large fast computers", "the first seminal paper on multiprogramming" [0].

From the discussion the followed:

E.F Codd (USA): an approach very similar to that described as been taken on the IBM STRECH computer [...] One of the most difficult problems is that of determining in a sufficiently general way, the best sequence in which problem programs should be brought in to the execution phase. Associated with this problem is that of storage allocation. Does Mr. Strachey have an solution (not of an ad hoc nature) to these problems?

C. Strachey: I have no solution.

From Time sharing in large fast computers by C. Strachey in Information Processing, 1959.

[0] The Evolution of Operating Systems by Per Brinch Hansen in Classic Operating Systems: From Batch Processing to Distributed Systems, 2001.

0 notes

Text

Liquid-Injection Thrust Vector Control

Lots of ways to control the attitude of a large rocket or missile come to mind. You can gimbal the engine. You can articulate the nozzle. If you're old-school, you can slap on some vernier thrusters or direct the exhaust with vanes.

There is, however, another little-known yet almost mainstream approach for attitude control in solid-fueled rockets: Liquid-Injection Thrust Vector Control.

By injecting fluids, a series of shock waves are selectively produced on the inner surface of the exhaust nozzle, which redirects the exhaust stream. [0]

This was the method used on the second stage of Minuteman II and III, as well as on the Titan IIIC solid rocket motors.

Now, combustion stability in rocket engines is hard. Liquid-fueled rocket engines are perhaps more well known for this phenomenon, but it affects solid rockets as well:

unstable burning, in varied guises, has been a frequent nemesis to the rocket designer. In fact, it may not even be an exaggeration to say that most rockets have been unstable at one time or another during their initial development. [1]

The acoustic properties of the nozzle also play key role [ibid], and "occasionally motors are approved even with low levels of oscillations" [2].

And yet, introduction additional shock waves was found to only be a feasible method of controlling a rocket, but in the right context, preferable.

--------------------------

PS

[1]'s introduction to the historical context of combustion instability is wonderfully droll:

Certain British rockets occasionally exploded "without cause" very soon after firing. Since the rockets were designed for release from under the wings of planes, and since the aircraft were not designed to survive flying through the fragments of their own rockets, this was a serious problem.

--------------------------

[0] Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare by David K. Sumpf (2021).

[1] Combustion Instability in Solid Rockets by R. W. Hart in APL Technical Digest.

[2] Combustion Instabilities in Solid Propellant Rocket Motors by F. E. C. Culick, Notes for Two Lectures given as part of the Special Course "Internal Aerodynamics in Solid Rocket Propulsion", 2002.

0 notes

Text

Rationale for International Standard—Programming Languages—C v5.10

§5.2.4.1:

While a deficient implementation could probably contrive a program that meets [the translation limits requirements], yet still succeed in being useless, the C89 Committee felt that such ingenuity would probably require more work than making something useful.

0 notes

Text

Atoms For Pace

Nuclear batteries create electricity from the decay of radioactive isotopes. A variety of methods are employed: radioisotope thermometric generators (RTGs) convert heat from the decay to electricity, while beta-voltaic cells capture particles given off by decay, similar to how a solar cell captures light. These devices are a common power source for space probes too far from the sun to use solar power. They had also found a niche in unmanned Soviet lighthouses in the arctic circle.

For a period in the 70s and 80s, they found another niche: the human body. Several companies offered nuclear battery cardiac pacemakers.

Its not as crazy as it sounds. The mercury batteries available at the time could barely last a few years. A nuclear battery could not only last years, but decades, perhaps an entire lifetime.

Being nuclear devices, safety was of course paramount, but surprisingly, for plutonium-power batteries, radiation was not the primary safety concern. It turns out plutonium is fantastically toxic, with blood levels as low 1 μg being fatal. It is also hypergolic with air, burning to produce a fine, radioactive dust. The batteries were therefore heavily shielded, against "incineration, airplane accidents, and direct gunshot wounds". With this level of protection, they increased patients' radiation exposure by less than 30%, low enough to be safe for pregnant women.

Overall, nuclear pacemakers appear to be a surprisingly practical solution. They fell out of use not through any fault of their own, but due to the introduction of lithium batteries and the rapid advance of electronics. Lithium batteries are able to power a pacemaker for 10 years, by which point technology had advanced enough to be worth replacing the entire device anyway.

Source: Nuclear Pacemakers (2005) by David Prutchi

0 notes

Text

Charlie's Chips

In 1883, if you got a chip in your eye, you called Charlie over to fish it out with his knife.

Charlie Westcott [the shop foreman], along with his other accomplishments, was quite an expert at removing all sorts of foreign matter from the eye. I remember one day when I was turning tool steel with my face rather close to work; suddenly I felt a stab of pain as a steel chip few up and sank into my right eyeball, blinding me in an instant.

"Charlie!" I yelled, clapping a hand over the injured organ, and executing a few impromptu dance steps in front of the lathe. Charlie dropped what he was doing and came running on the double. "What the hell's the matter, Freddie?"

"My eye-I've just put my eye out! I'm blinded!" And I started yelling again.

This was old stuff for Charlie. He acted promptly. Backing into a corner, he jammed my head tightly against the wall with his left arm and slipped out his pocket knife. Then, while I held back the eyelid with grimy fingers, Charlie dug his trusty knife blade into the cornea of my right eye. The steel sliver was in pretty deep, right over the iris where it couldn't be seen.While Charlie probed, I hollered.

"Go easy with that knife, Charlie-it's my eye you're fooling with!"

"Shut up and hold still. I almost had it that time."

"Leave me alone-I'll buy myself a glass eye in the morning." "Got it!" cried Charlie triumphantly, holding up the knife blade so I could see the sliver with my one good eye. It was at least a foot long, I thought, but when Charlie later got out the micrometer it measured less than 1/8 inch.

I might add that, thanks to Charlie's operative technique, my right eye is still as sound as the left, although I suffer from a slight case of myopia brought on perhaps by too much scribbling in the past sixty years. But that was how we lived in the heroic days before safety goggles were introduced.

Excerpt from 60 Years With Men and Machines (1947) the memoirs of Fred H. Colvin.

0 notes

Text

Nitrogen Blanket

Its fairly common knowledge that at high pressures, nitrogen has an drunkenness-like effect known as nitrogen narcosis. For example, at deeper depths, divers breath a mixture of air in which some or all of the nitrogen has been replace with helium. You certainly don't want to be drunk underwater! My diving instruction described it thusly: "So you're swimming along, breathing from your regulator. And you see a fish. But this fish doesn't have a regular. So you give the fish your regulator."

Winter et al[0] noticed that trace concentrations of of anesthetics could still have a noticeable effect on humans, and set out to measure impact of the nitrogen in 1 atm air on human performance. That is, they asked whether regular air is an anesthetic.

They tested 18 participants on a audio/video divided-attention categorization task, each with both air and a helium-oxygen mix (half got air first, then helium-oxygen; the others got the reverse order). Under all conditions, accuracy was greater than 97%, but there was a mean improvement in response time of 9.3% for helium-oxygen. An ANOVA revealed this performance difference to be significant, P < 0.001, while effects of practice and practice order x exposure condition were not significant.

Reviewing the findings and possible alternate explanations, they decide the evidence is in favor of this "nitrogen blanket" effect, and delightfully conclude

"[…] human history has proceeded under partial narcosis. Perhaps this explains the current state of world affairs."

--------------------------

[0] Winter, P. M., Bruce, D. L., Bach, M. J., Jay, G. W., & Eger 2nd, E. I. (1975). The anesthetic effect of air at atmospheric pressure. Anesthesiology, 42(6), 658-661.

0 notes

Text

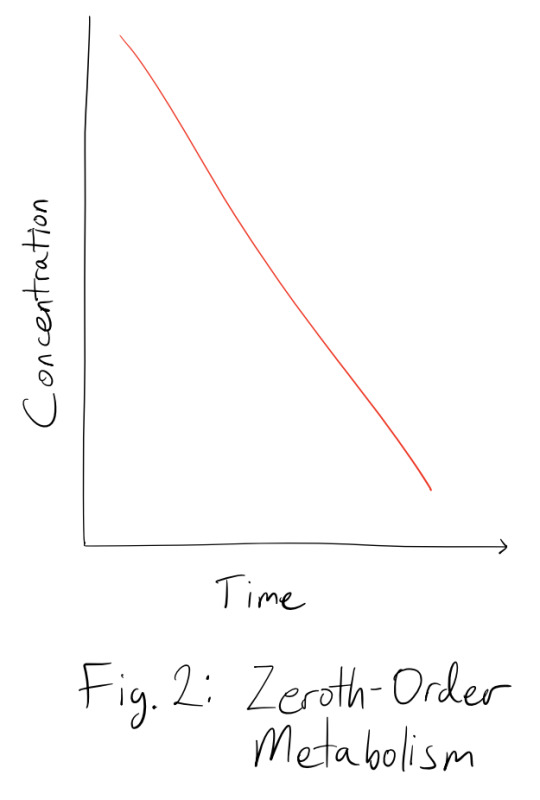

Kinetics and Dynamics (no, not those kinetics and dynamics)

Disclaimer: I'm not a healthcare professional. For entertainment only. I'm also going to be skipping over a ton of details. This is not intended to cover all cases.

Before I took a pharmacology class, I had a very mistaken idea of how drugs work. I'd assumed that the active molecules float about the circulatory system, being consumed by cells similar to how nutrients are consumed by cellular metabolism. Once the drug is "used up", I reasoned, the effect would wear off. Of course, when I was taught about hormones and neurotransmitters, their reversible binding was crucial to their functioning, but it never occurred to me to apply the same logic to drugs. Enter pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. I can't define them better than Wikipedia: "Pharmacokinetics is the study of how an organism affects the drug, whereas pharmacodynamics is the study of how the drug affects the organism."

So it turns out that the way drugs are not consumed in the process of affecting the body[0]. A typical[1] drug floats around, binding and detaching from receptors or enzymes. Eventually, its metabolized into an inactive form by the liver, and is eventually excreted. If you're a slow metabolizer for a particular drug, your blood levels will be higher for longer, and the drug will have a greater effect, and last longer; the converse holds for fast metabolizer.

This metabolism process is therefore pretty important to getting drugs into the right window where you experience adequate primary effects while limiting side effects - both the safety and efficacy rely on it. Typically, being a chemical reaction[2], reaction rate increases with the concentration of the reactants. The upshot is as blood levels fall, metabolism rate slows. In fact, once the concentration drops by half, reaction rate is halved, so halving the concentration again from 50% to 25% takes just as long as going from 100% to 50%. This gives us a half-life, much like nuclear decay. Figure 1 shows this effect (ignoring other aspects of pharmacokinetics, like absorption, distribution, etc.).

If you've ever asked a healthcare professional how long a medicine lasts, only to be given a much less helpful answer in the form of a half-life, this is why. They can't tell you when a medicine is "used up", because its not used up per se, and they can't tell you how long it takes to get it out of your system, because after a while the reaction rate is so slow that tiny bits of the drug will stick around for quite a while. Often, however, it doesn't take too much of a drop in concentration for the effects to diminish greatly. Its especially important to note drugs vary significantly in the relationship between concentration and effect.

Hopefully by now some of you are scratching your head, the way I did when I first learned this. While pharmacokinetics is not usually taught to the masses, there is one extremely widespread exception: alcohol. Many people were taught a rule of thumb, something like "one hour per drink"[3]. That's very much not the process I described above - alcohol clearing is apparently a linear processes.

What gives? The half-life decay process I described above is called first-order metabolism. It just so happens that the single most popular drug, alcohol, is a rare exception. The enzyme that catalyzes the first step of alcohol metabolism saturates quickly, preventing the reaction rate from increasing with concentration; a constant amount is cleared per unit time, termed zeroth-order metabolism[4].

So next time you have a drink, bask in the opportunity to totally overload your alcohol dehydrogenase.

---------------------

[0] Notable tiny quasi-exception: some drugs (termed prodrugs) are given in an inactive form, and are metabolized into their active form. The active form then generally behaves as per the above.

[1] I'm just sure there are lots of variations and outright exceptions. Again, not a professional. Talk to your doctor/nurse/PA/pharmacist.

[2] Not all chemical reactions follow this pattern, and the exact relationship varies.

[3] I am not endorsing this particular rule. Drink responsibly, etc., etc.

[4] There are other drugs that undergo zeroth-order metabolism, as well as multiphasic, an so on. Its a complicated topic. Can't you tell I'm trying to keep this simple? I'm glad you didn't ask about multiple doses and calculating steady-state concentration.

0 notes

Text

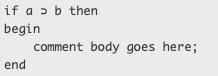

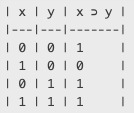

ALGOL's Making Implications

In the world of modern programming languages, we like to think we have the full complement of boolean operators[0], but there might be one we've missed. I recently picked up an ALGOL 60 book[1], and noticed it has an "implies" boolean operator, so you can write[2] something like

To save you from having to get out your truth table, ⊃ is

which is, of course, equivalent to ¬x ∨ y (or !x || y in C-land).

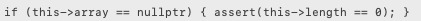

When I first read this, I wondered how it could ever be useful, but it didn't take long to remember a case where I wished I had it: asserts. For example, if you're implementing a vector in C++, you might want asserts at the beginning and end of each method to ensure object invariants are maintained. Once such invariant is that if the pointer to the backing array is null, the length field must be 0.

We could write this as

but then we'd be relying on optimization to remove the if when asserts are disabled, and its a little verbose.

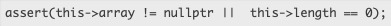

Using the equivalent form from above, we could transform it to

but this obscures our intentions.

Wouldn't

be much more elegant?

---------------------

[0] With the well-known exceptions of a XOR and NAND. Its common to see people asking why Dennis Ritchie didn't add a logical XOR operator (his answer), but according to my source, ALGOL 60 didn't have them either.

[1] Introduction to ALGOL Programming by Torgil Ekman and Carl-Erik Fröberg.

[2] Code samples given in the reference syntax used in the ALGOL reports. The publication syntax use for publishing algorithms and the implementation syntax used for writing programs on a computer may differ, although in practice the reference syntax and publication syntax were the same.

1 note

·

View note