A blog about life in colonial acadmia, political theory, political organizing, coloniality of power, history of colonialism and decolonization, neuro-queerness, labor, revolutionary memory, spirituality & affect, and more.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Humiliated and the Disappointed

My dissertation might well just be a very long winded intellectualization of a similarly long ass politically depressive episode in my life. Hannah Proctor understands political depression as, ironically, an experiential non-relationship between politics and depression, which could be thought of “as a problem of scale in which an individual loses all sense of their connection to larger structural forces” (65). To me this is tempting, and in fact it makes me feel seen. But this resonance risks naturalizing the toxic desire for subjectivity, the capacity to write yourself into history, or position yourself as “making” at least some tiny little bit of history and intervening in structural forces. There is a nauseating texture to this way of thinking. In fact, yesterday while I was stuck on the highway listening to Ayman Makarem’s recent podcast episode on existentialism in the age of genocide, I literally felt that nausea messing with my emotional turmoil. How do I put it? The modern colonial subject is this thing that haunts the body, something that somehow cannot simply be exorcised through a ritual. When you dream at night, and the dream’s content is blurry but the emotions and sensations echo deeply with you, you wake up remembering feeling seen by a dream. But it is just that, a dream that somehow gets you more than “yourself”. And this is perhaps one way to describe the feeling of political depression. A dream-like experience that threatens to totalize one’s lived reality. Maybe threat is inaccurate, maybe it is seduction, manipulation, normalization, or just a habit. I wanted to vomit it out.

My project, particularly the chapter on leftist attachment to Maoist imageries as shown in the Jasic case, attempts to offer neither a diagnosis nor a cure for political depression, but to ground analyses of it with its epistemological and affective conditions of possibility. For the most part, both Proctor and Makarem’s experiential discussions of political depression share the tacit assumption that depressive state is a problem, somewhat of a predicament to political action, and defined by multidimensional political inaction (inability to act, unwilling to act, the impossibility of action, uselessness for actions, etc.). Through reading Shulamith Firestone’s political manifesto alongside her latter, depressive fiction, Proctor is insightful in suggesting that the political and the depressive are mutually illuminative (77). But it also seems to hint at the possibility that the political is condemned to be depressive, which is ironically non-political. Entangled, “The boundary between the politicized and the depressive becomes porous.” (82) The types of post-revolutionary loss that I discuss in the chapter might not be depressive in the medical sense, but its politics of the futures past might help understand the difficulty for the academic left to prioritize building relationships with the hypocenter over engaging in discursive war in the epicenter (it is not a zero-sum game, to be sure).

Even though she is careful not to conflate radically diverse movements and phenomena in this broad analysis of political defeat and relevant emotions, Proctor is simultaneously discussing two types of political depression in chapter 3. One is of the nature of colonial fragility, sourced from the injured ego in her inability to act politico-historically, the other deep disappointment about how egotism ruins hopeful spaces which are “the movement”. It is the latter that is deeply intriguing to me, “The solidarity of disappointment may not be a straight-forwardly joyful bond but it provides an alternative to atomization.” (83) She said so in passing, as if the solidarity of disappointment has an agency in itself moderating all the meetings, initiating all the difficult conversations, making all the dinners, and holding the space for trauma bonding together. Someone’s gotta do it, and when people are back to normality, that someone’s gotta bear the cost of an empty nest. The improvising, prefigurative maternal has not complained loud enough, therefore she is not heard.

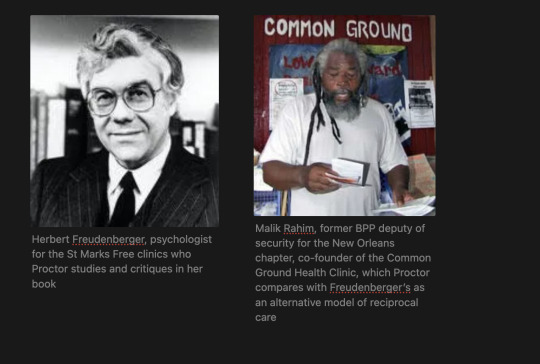

The relationship between the disappointed and the humiliated is further revealed in her chapter on burnout, in which she glues them back together through a means-end relation. The humiliated, in this case the free clinic psychologist, find himself incapable of caring unconditionally without burning out, essentially and eventually assimilating with the society he tries to resist. The disappointed, in this case the gay “first responders” to the AIDS crisis who took over the free clinic she traces, who is incapable of, but perhaps also does not have the privilege of, synchronizing with the victors (86), weaves new webs of care to sustain the radical mutual aid infrastructure. On that Proctor makes two observations. First, that

“it is possible - and necessary - to sustain projects over long periods despite the toll it takes on the often overworked and un(der)paid people involved. If looking after other people or giving up time to help others can be draining, the solution is surely more care and more reciprocity, rather than less.” (100)

And second,

“These models of networked care come closer to providing an antidote to burnout than anything else I have come across - short of social transformation, and there’s the rub. Ameliorating burnout might rely on small-scale initiatives in the short-term, but as a means rather than an end.” (102)

From this, I see a questionable model of relationship between the disappointed and the humiliated. The former stays and heals, the latter ghosts and withdraws. The former is prefigurative and nurturing, the latter is strategic and preoccupied with winning. The former is a part of the latter, the latter somehow guides the former.

Proctor, Hannah, 2024, Burnout: The Emotional Experience of Political Defeat, NY: Verso.

0 notes

Text

Rattling the Cages & Mental State

Sitting down and actually reading a book for a prolonged period of time have been a luxury these days. My body seems to detest the state of rest, calmness, joy, and study, and instead it is filled with guilt, sadness, and fatigue amidst the ongoing genocide in Gaza. Well, I don’t find satisfaction in words like “boundary”, “capacity”, and “sustainability”, all of which have helped me practically but entail notions of colonial management that should be resisted. But I was revisiting the Eight Rules On the Nature of War article by Basel Al-Araj since I was translating a previous post for the Pal Solidarity Zh Network, and looked at it from a new perspective. I would say Basel was in a state of being in touch with the real and materiality, meaning that what motivated him had moved beyond emotionality, immediate gratification, affective attachments, and mental/intellectual activities. His words point to a state of being, of engaging in resistance simply as it is supposed to be. It is against this background that I pick up the book from where I left it at, seeking something that could ground me more profoundly and with conviction.

Maintaining a mental state suitable for sober learning and deep studying of the surrounding and your enemy is crucial for not only the survival but also the archiving of lived experiences of political prisoners. And this is not a given. You need to be calm enough to discern the rules of the institutions as well as their changes, before making any presumptive moral judgment to it. This is particularly difficult in an environment of psychological warfare, i.e. the carceral system, where one of the primary goals of your enemy is to drain you of your will to resist. This will, as a state of being, is the only thing that set you apart from your enemy as they imagine all the tortures that they themselves fear and the rewards that they themselves desire as sufficient means to contain you. What truly ground people are, unsurprisingly, things close to spiritual teachings that modern secular education, cult-like religions, and the infantilizing psychiatric industrial complex stripped us of.

The present (”……it is all temporary…….You don’t have to endure a year of whatever condition…or a month…or a week. You just have to survive through today. Just today. And you know you can do that because you survived yesterday. In that sense, I didn’t survive a year of torture; I survived one hour of it…twenty-four times in the course of a day…and I survived a day of it…365 times”, Sean Swain, p. 102)

Entangled Others (”I didn’t own me; too many others did. They were invested in me with love and blood and sweat and tears, and I owed it to them to get through everything by whatever means.” Sean Swain, p.102)

Adaptive Flexibility (”You adapt. As human beings, in and of ourselves, we are adaptive to certain circumstances and situations, and so we adapt. I adapt. By adapting, I continued to study and continued to organize. That’s how I survived in the prison system.” Jalil Muntaqim, p. 120)

Unapologetic Authenticity (”I made a conscious decision early on to be who I am. I won’t be anything else, won’t pretend to be. I associate with people I respect, and I value opinions of people I respect. Everyone else can fuck off. I don’t need their approval. I’m not adhering to anyone else’s sense of what I ought to be or who I should avoid.” Sean Swain, p. 105; “……we are not here to keep our heads down. Wherever you’re at, that’s where the battle lines are. I was never the person to just play along and compromise my principles. Just me being who I am, interacting with people and going against the grain, definitely got me in problems, especially the first time. Fortunately, there were people who respected that too. I was kind of taken in as well by other people.” Jeremy Hammond, p. 133)

Low Expectations

I find it hard for me to resonate with the aesthetics and practices of revolutionary self-evolution (self-improvement) and organized religion, articulated by people like Jalil Muntaqim and Grace Boggs Lee. But leave that for some other time.

0 notes

Text

Reversed Devil

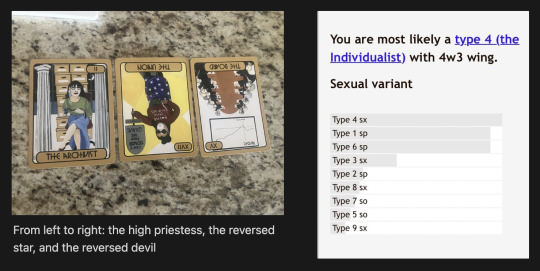

I stayed up last night till three or four am thinking about my fucking dissertation and the lamenting how fucked up colonial academia is, and then feeling shitty about feeling shitty, and did the Enneagram Test just for the meme and felt personally attacked once I checked the explanations on the Funky MBTI site a friend sent earlier. I don’t really remember the conclusion from the late night brain fog but I think I was getting ready to not really do this academia thing and find my rigorous and principled intellectual community elsewhere. I still need to get things done and finish the degree to at least get a teaching job that I want to do, and I will still need to be good at it (which I feel confident), but the sheer mediocracy of professional academic research is such a waste of time. I simply do not understanding the meaning of publishing, grant and fellowships, the politics of recognition, the customs of obedience, and more. And if I want my work out there, just make sure to write a decent enough dissertation so that people can check it out in the future. And even if I stay in here, I am here for the outsiders inside and nothing else.

This morning a drew a set of cards from my Academic Tarot deck to signal the past, present, and future of my relationship with colonial academia. In the past I’ve always been confident about my intelligence but extremely unsure about this whole academia thing. It was really coercive sociality that got me into deciding to commit to it at least for a little bit (meaning, as I made more friends “in” academia I oriented myself and my lives around it more out of masking habits and the desire to be recognized and accepted). Although my intuition told me something was whack and fundamentally rotten, the predatory nature of academic sociality means that it gives you insufficient but just enough of what you need in a world where alternatives rarely exist and are unimaginable. In my case, what I needed, and still need, was a vibrant collective intellectual life in pursuit of collective liberation. I have been lucky enough to be able to assert my own intuition and scramble to find my own spaces by sticking to what makes the most sense to me, even though, of course, these are far from perfect or enough. Intuition, empathy, and compassion are not the most rewarded in academia, even the pretense of them eventually revealed themselves as a mere remodeling of the same old modern-colonial house. This has transitioned me from being a humble imposter seeking approval to a grumpy outcast filled with contempt. The (long ass) present is when everything that was once joyful, or more importantly meaningful, to me now seems like too much to handle emotionally and existentially. The rotten foundation of academic freedom and knowledge production, along with the “intellectual communities” once seemed committed to justice, truth, and collective struggle towards liberation to me, is increasingly unsaveable and irrelevant to my life. The Reversed Star reminds me of the importance of care for myself and my community. And the Reversed Devil card for the future says:

“Reversed, drawing The Board suggests that you are now in the process of remembering that you are free. If you can move beyond the precipice of fear, rage, and anxiety, now may be a good time to talk with a friend or therapist. You can overcome the feeling of being trapped.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Collaborator Sociality

A friend recently asked me if I could recommend any scholar in memory studies for a conference she is organizing for next year, since she knows this is one of my fields. I honestly cannot. Having been through the past 8 months and witnessed the culture of obedience in the academe, I do not know any career academic that I truly respect and trust politically at this point. Against this backdrop, I was working on a project on the politics of divestment campaigns in the imperial core and trying to think through the affective dimension of things. I picked up some of the articles in the recently published issue of Parallax on “feeling implicated” as a political affect. Michael Rothberg wrote an interesting introduction to the issue, elaborating his thoughts on how affect theory can contribute to an understanding of the implicated Subject’s entanglement with violent institutions, systems, and structures. I searched him up, thinking that there’s no way a scholar of the memory of the Holocaust can be pro-resistance, and here we go, I found an open solidarity letter he wrote for someone (see below). A boring and typical liberal Zionist anti-fascist approach to “pro-Palestine” solidarity. Meanwhile, he’s also one of those FJP members at UCLA who signed on to their department letter against the university admin’s use of police force against student protestors in the past months. A part of me feels like it would be interesting to put his intellectual project in perspective of his (classic FJP) political positionality.

I remember bro Diallo said something like this: under a system of oppression, there are only three types of people among the oppressed, those who resist, those who submit, and those who collaborate. You side with the resistors, educate and help the submitted, and the collaborators are your enemies. Approaching this with the intentionality of collective study, however, I wonder what else is to be said and thought about when it comes to things like divestment. It is probably time for a conversation about whether or not divestment is collaborative with the colonizer. And my whole point is that it is. To produce critical knowledge that examines the movement with a certain kind of sobriety, I look to models like classist safety (formerly firstgensafety) on Instagram. I really hate the wishy-washy academic type who talks about accountability theoretically but when it comes down to actual politics, their liberal upper class positionality will be exposed in a second. And divestment is kind of the litmus test to colonial politics, just as Palestine is to transitional justice. The hyper-excitement around and mobilizable-ness of divestment, with the majority middle class base supporting it, does not offer me any confidence.

We are situated in a very weird moment, filled with the fantasies, learned helplessness, and melancholia of post-coloniality, while ongoing colonizations are happening. And so the majority of social justice discourses and their advocates look at Palestine from the standpoint of time travel, of anachronism. The rhetoric of anti-colonialism in the post-colonial present is just that, rhetoric. This is why anti-colonialism becomes absurd in the public imagination, and Palestine becomes something wildly disturbing, not merely due to the live streamed atrocities, but also its disruptive effect on the post-colonial mind that deems resistance as undesirable, impossible, or at least complicated. I am not even talking about the mass that are inculcated by settlerism as an ideology, btw I don’t even think if we can have a communism without settler colonialism, in response to J. Moufawad-Paul’s position**.** I find it disturbing that settlers who benefit from the system move to innocence so quickly by reducing settler colonialism to garrisons, a fundamentally militarized structure of conquest, thus bypassing other forms of settler colonialism in the ontology of the state, the metaphysics of historical progress, the civilizational missions of education, governance, and economy, etc., that they themselves are more deeply involved in.

1 note

·

View note

Text

(De)activation

Recently I heard from a friend about the differences between therapeutic activation and pedagogical deactivation of trauma, which has been super thought-provoking for me. At times it has been really difficult to tell between a cathartic and healing activation from a triggering and damaging one. Right now, for example, I am feeling this strong irritability in my own body. The sense of disapproval from closed ones is a stressor that works particularly effectively to activate me. A slight disagreement from someone in my beloved collective, the failure to acknowledge my labor from a trusted friend, the feeling of being perceived as the killjoy in my supposedly progressive extended family, my partner’s compulsive care in a time of crisis that smells like distrust to me when it catches me in a bad moment, the dreading fear for calling my own parents and potentially getting their disapproval for the political work I’ve been doing, etc. I don’t know what’s next for responding to this affect theory of mine, a body protected by too thin of a layer of skin to be hermetically sealed from others.

In the past weekend, I had a hilarious incident that literally cut my skin apart. Our family walked the dogs outside on Saturday afternoon, and the husky was with me. She, being a husky, was way too excited and trying super hard to sprint at full speed despite being on the leash. At the time I had an empty stomach and was starting to feel dizzy, perhaps due to low blood sugar. She just went on jumping up and down, until eventually, she flew me like a kite in the air. I was not aware of what happened until gravity brought me back to the ground, hitting me hard on the left knee, the right hip, and my right elbow. It HURT like a bitch. She went off leash and ran away immediately, then paused as she realized she might have killed me, returned to me and checked if I was alive, with her mischievous husky face. A second later she was like “oh cool you’re alive okie bye”. And took off like a silly. A group of community kids on scooters finally got her and everything was fine. It was just so funny and typical husky. I guess the point is, this is clearly a case of harm infliction, and it requires an immediate response of harm reduction and first aid support. I think the world as we know it at best approaches the ongoing genocides in Palestine, Sudan, and Congo through this narrow and shallow framework of infliction.

But I really think it is important to start thinking about the deeper layers of (de)activation. This world as we know it is constituted by lands and bodies that carry centuries of wounds and traumatic memories from coloniality, raciality, modernity, capitalism, and more. And what happens is multi-layered trauma responses and cures. Unprocessed wounds demobilizing people upon activation by witnessing political violences, latent wounds transformed into activated monstrosity of genocidal machines, organizing efforts seeking to heal collectively through political agitation as a gentle and controlled activation of trauma, pedagogical deactivation of the modern Subject’s fear for the messages to land, and more. At the moment I just feel like my body is so over-activated that I am getting to a point where I think collective healing might not be possible for us in this liberation work, if we are to be seriously honest to ourselves. But at least I should rest for now.

0 notes

Text

Regressive Justification

Ok, now that it seems conclusive that the deontological, individualist formalism in the Kantian tradition, which relies heavily on fictive formulation of the original contract, can be thrown out of the window. But hold on a second, as moderate and eclectic as Ricoeur is, he is never about fully rejecting anything. To him, the merit of his narrative approach derives from the patient long detour it takes. In the third study, this is first contrasted with Kantian formalism’s hasty universalization, and then put in conversation with Habermasian communicative ethics. He made a pretty helpful distinction between regressive justification and progressive actualization. The former requires morality to be constantly justified by ethical intuition, whereas the latter continuously moves morality forwards for its fulfillment. Recall the threefold relationship between ethics and morality at the beginning of the third study: 1). the primacy of ethics over morality; 2). the necessity to test ethics through the sieve of norms; and 3). the necessity to return to ethics as practical wisdom. We have arrived at the third step, through which the inevitable conflicts between universal moral norms and concrete situations. This conflict was explored in the second step, which further justifies the first step (primacy). The question is, now what? He summarizes it as “practical wisdom” that

“has no recourse,……, other than to return to the initial intuition of ethics, in the framework of moral judgment in situation, that is, to the vision or aim of the ‘good life’ with and for others in just institutions.” (240)

Note that this is neither about inventing a third agent for judgment nor about disavowing moral maxims once and for all, but a balanced dialectical relation between moral obligations and convictions. But what exactly does he mean by “conviction” and/or “ethical intuition”?

Tame the Monster

He wrote this chapter amidst his son Oliver’s fatal suicide. The Interlude, “Tragic Action”, is an attempt to cope with the personal pain by being honest about the limitations embedded in moral prescription. It is this limitation, one which creates contradictions in every corner of human moral life, that Ricoeur’s narrative self seeks to confront instead of avoiding. It is here that you get a glimpse of what he means by “fiction”: a compulsive avoidance of contradiction in contractualist moral theories. A self-deceptive cover-up of conflicts in human social life, both subjective and intersubjective ones, toward various forms of solipsism. Here, he resorts to the otherworldly realm to describe the indescribable that “intrudes” into the sovereign design of narrative coherency. Spiritual powers, archaic and mythical energies, divinities of the underworld, mysterious depth of motivation, Catharsis, ritual, all of which are terms he uses to point to the “finality of the tragic spectacle” that “infinitely exceeds every directly didactic intention.” (242) We can indeed read this as a continuation of the core theme in Time and Narrative volume one, the dialectic between discordance and concordance. Again he directs us to the ultimate limitation of the human, all too human, character of every institution. (245)

With this emphasis on the non-philosophical dimension that tragedy dwells, we venture closer and closer to a post-humanist Ricoeur, one which is willing enough to reject the illusion of and attachment to humanism. But not quite, as in other discourses of tragedy in political theory (Nussbaum’s and Scott’s, to name a few). He proceeds through the aspirational notion of poesis, deinon, one of ambiguity that oscillates between admirability and monstrosity. It is clear here that his is an essentially pre-humanist vision with a post-humanist ambition and an anti-humanist potential. This in-betweenness of the tragic allows him to land at the teachings of “think correctly” and “deliberate well”. (247) It is an important point that’s worth quoting at length,

“Taken as such, tragedy produces an ethicopractical aporia that is added onto those that have appeared throughout our quest for selfhood; it repeats, in particular, the aporias of narrative identity that were identified in the preceding study. In this respect, one of the functions of tragedy in relation to ethics is to create a gap between tragic wisdom and practical wisdom. By refusing to contribute a ‘solution’ to the conflicts made insoluble by fiction, tragedy, after having disoriented the gaze, condemns the person of praxis to reorient action, at his or her own risk, in the sense of a practical wisdom in situation that best responds to tragic wisdom. This response, deferred by the festive contemplation of the spectacle, make conviction the haven beyond catharsis”

The conflict, as an inevitable product of the encounter between the irreducible singularity of the character and the one-sidedness of the moral principle, can be a productive one insofar as it transform the tragic to the practical. Such reorientation only takes place in actions, sheltering “moral conviction from the ruinous alternatives of univocity or arbitrariness”, that is, from the tragic monsters. (249)

Tragic Drama After the Subject

It is clear here that an emplotment is at work without the author’s explicit acknowledgement. The failure of moral principles, the death of the Subject, the inevitable clash between the universal and the local. Life is too complex to plan around and it is this complexity that conditions universalism to its ruinous tendency. Wonderful, Ricoeur, why insist on the universal as a mediator of the tragic though? We soon realize he’s talking about the grammar of the modern Subject, the myth of universal individualism, the paradox of its contradiction with concrete individuals. He is talking about the fact that modern culture is a culture of death, which reminds me of Klee Benally’s quote of John Trudell in No Spiritual Surrender,

“This thing called technologic civilization wants every human being—it tries to break the spirit so the mind will surrender. We aren’t put here for that. Everything that happens in our life is a series of experiences. If we understand that, maybe we can truly learn something from those experiences. What I do know is that I come from a culture that is deeply rooted in the whole idea and reality of the continuation of life. And I’m dealing with another culture whose perception is a reality of death.” (27)

Lamenting this exact same perceived reality of death, Ricoeur strives to denaturalize the ruins by charting out a regressive route and demanding progressive history to happen slower. Tragedy is thus a friction of history, something that can and should be managed and minimized but not eliminated. The messages are clear. First, life without modernity is unimaginable, as the tragic signals a deadlock for thinking a way out of the Subject’s inevitable confrontation with conflicts and the destruction these conflict entail. Second, reform modernity, so that it could prioritize life rather than death by reorienting its responses to the ethics-morality conflicts. We are once again reminded of his core concern throughout the book: expanding the narrative capacity of the self in favor of ethical, intersubjective relationship building. This is where conflicts appear problematic, albeit inevitable, as they represent the violence of moral principle in seeking to actualize itself at a large scale.

Conflict One: Senses of Justice vs. The Spirit of A People

This regressive justificatory route first takes us to reexamine Rawlsian formalism, particularly its procedural understanding of justice as fairness. To Ricoeur, this conceals the deep conflicts, given the fact of diversity in human society, between different visions of what qualifies a good as good. What Rawls offers is thereby at best a considered guess and teleological in nature. Even when political theorists, such as Michael Walzer, try to diversify the list of goods to match with the complex reality, problems continue to arise insofar as such lists can never exhaust concrete possibilities and options emerge in real politics. Given Ricoeur’s primary ethical concern, the problem of arbitrariness cannot be resolved by given a third entity, such as the state, the sole authority to exercise arbitration. By tracing the Hegelian tradition of abstract right that regulates the triangular relationship between a will, a thing, and another will, Ricoeur points out the fundamental weakness of it: its juridical atomism renders the discussion of concrete, connected persons impossible. And this is why the contractualists are condemned to hold only a fictive account of the contract, as there’s no feasible way to actualize such contract and put it in place in real life. He thus posits civil society as the dialectical anthesis to organic bonds, interpreting Hegel’s Sittlichkeit (ethical life or ethical order) as

“……on the one hand, in the sense of the system of collective agencies of mediation interpolated between the abstract idea of freedom and its realization as “second nature” and, on the other, as the gradual triumph of the organic bond between men and women over the exteriority of the juridical relation (an exteriority aggravated by that of the economic relation)…….” (255)

Therefore, there is no solid grounding for obeying the Hegelian state constitution, endowed with self-knowledge, insofar as we turn Hegel upside down. Here, Ricoeur implicitly reminds us of the fact that he is indeed a socialist-Marxist, particularly one that aims at demythifying the liberal fascist state. Here is a beautiful paragraph of Ricoeur’s anti-fascist manifesto:

“What, finally, is inadmissible in Hegel is the thesis of the objective mind and its corollary, the thesis of the state erected as a superior agency endowed with self-knowledge. Most impressive, certainly, is the requisitory that Hegel addresses against moral consciousness when it sets itself as a supreme tribunal in superb ignorance of the Sittlichkeit in which the spirit of a people is embodied. For us, who have crossed through the monstrous events of the twentieth century tied to the phenomenon of totalitarianism, we have reasons to listen to the opposite verdict, devastating in another way, pronounced by history itself through the mouths of its victims. When the spirit of a people is perverted to the point of feeding a deadly Sittlichkeit, it is finally in the moral consciousness of a small number of individuals, inaccessible to fear and to corruption, that the spirit takes refuge, once it has fled the now-criminal institutions. Who would still dare to chide the beautiful soul, when it alone remains to bear witness against the hero of action? To be sure, the painful conflict between moral consciousness and the spirit of a people is not always so disastrous, but it always stands as a reminder and a warning. It attests in a paroxysmic manner to the unsurpassable tragedy of action, to which Hegel himself did justice in his fine pages on Antigone.”

Ironically, what does it mean to be a conflict-avoidant Marxist? Sociologists nowadays categorize Marxism as conflict theory, which says a lot about the anti-communist traces of social sciences in the United States amidst its ongoing Cold War with imaginary enemies. We see transference happening at the textual level here as Ricoeur moves from critiquing the normative foundation of political theory to the catastrophization of the state’s monopolization of power. Totalitarianism as the tyranny of the collective constituted by inorganic civic society, as a theoretical framework, amounts to a post-trauma magnification of fear of the liberal state, despite its analytical efficacy. By using the emplotment of tragedy, Ricoeur interprets it as an inevitable historical aporia and seals the possibility of anti-totalitarianism. The job is to continuously renarrativize the self toward the ethical to tame the tragic, not to launch yet another political project but to engage in some sort of harm reduction work.

His critiques target the mythification of the Hegelian liberal state, that is, the myth that separate the political from the ethical, not the liberal state per se. It is this mythification that allows Hannah Arendt to distinguish power (and thus the political) from domination. But Ricoeur notes the arbitrariness of such separation by unpacking the political paradox at work, in which “form and force continue to confront one another within the same agency……force and form are conjoined in the legitimate use of violence”. (257) We can take a glimpse of his agonistic democratic idea in his definition of *the political “*as the sets of organized practices relating to the distribution of political power, better termed domination.” (257) With this he marks three spheres where political conflicts occur: 1). deliberative democracy (with rules of the game largely agreed upon); 2). political philosophy (where the ends of “good” governments are debated); and 3). democratic legitimation (via which the desire to live together is called into question).

With this he returns to the senses of justice, for which equity is another name. Drawing from Aristotle he notes that equity should take primacy as it remedies the rule of justice “where the legislator fails us and has erred by over-simplicity”. (262)

Conflict Two: Respect for the Person vs. Respect for the Rule

Ricoeur returns to the discussion of the Kantian maxim against false promise, this time taking a second path of concretization/application in the strong sense. Again, the problem with Kant is that his argument does not allow others to actually be taken into consideration. Instead, it is solely tested by universalization and internal coherence at the detriment of otherness. The only exception made, throughout his works on false promise, is when such action is justified and necessitated by self-love. Ricoeur counteracts this by submitting the moral rule to another set of test: “that of circumstances and consequences”. (265) Through this second path one can start asking whether and how the genuine otherness of persons can make ways for exceptions. He points to the plural structure of promises, which engage the actor, the receiver, the witness, the language subtext, and more, that resembles that plurality of the political discussed above. For the sake of the discussion here, he limits it to the dialogic-dyadic (involving two persons) structure of promising, or self-constancy. He notes,

“The obligation to maintain one’s self in keeping one’s promises is in danger of solidifying into the Stoic rigidity of simple constancy, if it is not permeated by the desire to respond to an exception, even to a request coming from another.” (267)

This simple constancy locks the self in her hermetically sealed individuality, one that has to be broken open to be able to establish the principle of reciprocity. Thus, Ricoeur proposes the idea of “availability”, a radical openness to the dialogic-dyadic structure and solicitude that are erased by the field of legal norms. Availability entails the capacity to improvise conducts “that will best satisfy the exception required by solicitude, by betraying the rule to the smallest extent possible”. (269) This is particularly relevant in cases where the rule creates suffering, and practical wisdom is called for to mediate between such suffering, on the one hand, and happiness, on the other hand. Harm reduction again comes to my mind when reading these lines, where sufferings are exceptions, not the rule per se. He is navigating the ambiguity between the majority cases of goodness of the rule and its minor opposite of ruins. This proportionality judgment also guides his latter comments on the ontological division between human and things in these moral rules. Again, there’s an ambiguity between the majority cases of clarity of what a human is and its minor opposite of in-betweenness (he uses the example of an embryo to demonstrate the idea of a potential humanity). Practical wisdom, as he shows in these example, is not universalizable though not arbitrary, and it takes plural voices of the most competent and the wisest to reach. (273) He concludes this second conflict at the interpersonal level,

“……one can say that it is to solicitude, concerned with the otherness of persons, including "potential persons," that respect refers, in those cases where it is itself the source of conflicts, in particular in novel situations produced by the powers that technology gives humans over the phenomena of life. But this is not the somewhat "naive" solicitude of the seventh study but a "critical" solicitude that has passed through the double test of the moral conditions of respect and the conflicts generated by the latter. This critical solicitude is the form that practical wisdom takes in the region of interpersonal relations.” (273)

Conflict Three: Contextualism and Universalism

This is the part where I am almost convinced that Ricoeur is on the same page with da Silva. After the long detour, we finally arrive at where we started: autonomy. In this last step, Ricoeur embark on a journey of completely revising Kantian formalism, not to refute it, but to allow the full mediation of the confrontation between the universalist claim and the historically-contextualized and communitarian ones. To do this he asks three questions. First, why give autonomy the priority? This method of reading backward exposes the arbitrariness of autonomy as a foundation for Kantian maxim, as there’s no solid “complete determination” without the backward testing. (274) Kant continues the aporia of selfhood that appeared in the preceding studies, which is Ricoeur’s way of naming the transparency thesis’ assumed homogeneous interiority and self-evidence of selfhood. To Ricoeur, “Dependency as ‘externality’, related to the dialogic condition of autonomy, in a sense takes over from dependency as ‘interiority’ revealed by these three aporias” (of reason, respect, and will). (275) The teachings and offerings of otherness is completely erased in Kant.

Second, why is autonomy the metacriterion for universalization? Kant reduces the universalization to noncontradiction, which appears to be extremely restrictive and limited when applied to concrete historical locations. Ricoeur moves on to compare Kantian moral coherence (pre-supposed, hierarchical, mutually non-exclusive, not vacuity) and legal coherence (case-based, inventive and constructive alongside the emergence of new cases). He offers a sharp comment that,

“……besides the procedures of constructive interpretation similar to legal reasoning, moral philosophy has to incorporate a sharp critique of prejudices and ideological residues in its enterprise of reconstructing the specificatory premises capable of assuring the fragile coherence of the moral system. It is here that rationalism unexpectedly crosses paths with tragic wisdom: is it not true that the narrowing affecting the vision of "spiritual greatness" that the two protagonists of Sophocles' Antigone are held to serve has as its equivalent, on the plane of moral theory, a perverse use of the "specificatory premises" that have to be unmasked by a critique of ideologies?” (280)

Third, what keep the autonomous self and the law in sync? This is a further investigation of the Kantian legacy through the works of Karl-Otto Apel and Jurgen Habermas, which contains the paradox of concealing conflicts emerges in situation through devising sets of communicative ethics. To begin with, Apel makes an important intervention to Kantian transcendentalism by reconstructing the test of universalization through the idea of “performative contradiction”. Autonomy, or the self-legislative character of freedom, is thus protected from the critique above, of its easy disruption by imperfect coherence. Ricoeur summarizes that:

“Transcendental pragmatics repeats, in the practical field, the Kantian transcendental deduction by showing how the principle of universalization, acting as a rule of argumentation, is implicit in the presuppositions of argumentation in general. The presupposition of an "unlimited community of communication" has no role other than to state, on the level of presuppositions, the perfect congruence between the autonomy of judgment of each person and the expectation of consensus of all the persons involved in practical discourse.” (282)

Following Habermas’ critique, he notes, “The recourse to performative contradiction, for Habermas, denotes nothing more than an admission that there exists no principle of replacement within the framework of argumentative practice, without this transcendental presupposition standing as a final justification.” (283)

The Habermasian Solution to The Conflicts, Reformulated

Habermas refutes transcendental pragmatics as it provides insufficient justification for argumentative practices. First, on the plane of just institution, the reason the communicative ethicist wants to offer such justifications is the unsatisfactory, procedural theory of justice that liberalism presents. As Ricoeur marks, “every distribution, in the broad sense that we have attributed to this word, appears problematic: in fact, there is no system of distribution that is universally valid; all known systems express revocable, chance choices, bound up with the struggles that mark the violent history of societies.” (284) It does necessitate a contentious process in establishing just institutions, and to Habermas, such process is argumentative. Second, when it comes to interpersonal relations, the conflict between universal humanism (of “rational beings”) and concrete situations, generates debates about what it is to be respected that mediating between the respect of rule and respect of persons. Thirdly, the conflict between the universalization of autonomy and the violences it generates requires a cautious look into its route of application. With the three conflicts above, Ricoeur thus sets the stage for Habermasian ethics of communication or argumentation. Note that by critiquing the universalism of Habermas, he is by no means endorsing contextualism wholeheartedly, because to him, there’s no contextualism if there’s no universalism. They are the two sides of the same coin. What he suggests is to recover the bridges between contextualism and universalism, against their false division and dichotomization.

In Habermas, it is the familiar Kantian impulse of purification that leads to such division. “Convention” to Habermas is what “inclination” is to Kant. To Ricoeur, this has to do with the specific interpretation of modernity exclusively as a definite break with a past of tradition and authority, where norms are not to be publicly debated. Critiquing the antagonism between argumentation and convention, he reformulates communicative ethics as a subtle dialectic between argumentation and conviction, which “has no theoretical outcome but only the practical outcome of the arbitration of moral judgment in situation.” (287) Except for the fact that it carries the requirement of universalization, argumentation is like any other language games. This means that it is operative

“……only if it assumes the mediation of other language games that participate in the formation of options that are the stakes of the debate. The intended goal is then to extract from the positions in confrontation the best arguments that can be offered to the protagonists in the discussion. But the corrective action of the ethics of argumentation presupposes that the discussion is about something, about the ‘things of life’…….argumentation is not simply posited as the antagonist of tradition and conviction, but as the critical agency operating at the heart of convictions, argumentation assuming the task not of eliminating but carrying them to the level of ‘considered conviction’, in what Rawls calls a reflective equilibrium”. (288)

Here, we finally arrive at a Ricoeurian atemporal modernity. Similar to Amy Allen’s critique of Habermas, Ricoeur rejects the progressivist notion of modernity embedded in the latter’s communicative ethics. It is unclear throughout the text, however, what modernity means to Ricoeur.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Normative

In Oneself as Another, Paul Ricoeur arrives at a narrative conception of the self through a long hermeneutic detour mediating between the descriptive and prescriptive approaches. The narrative self, according to him, is characterized by the narrative reconfiguration of actions, the devising of life plans, and the narrative unity of a life. He further argues that this narrative conception necessarily entails the primacy of ethics over morality. Here, he distinguishes ethics from morality, as the former is explicitly teleological while the latter is ostensibly deontological. By ethical aims, he means the narrativization of “the good life with or for others in just institutions”, gesturing towards self-esteem. By moral aims, he means “that which is considered to be good and of that which imposes itself as obligatory”, that is, they are “norms characterized at once by universality and by an effect of constraint” (170). The moral therefore aims at self-respect in accordance with laws. The third part of this book is all about clarifying the relationship between ethics and morality, which he emphasizes,

(1) the primacy of ethics over morality; (2) the necessity for the ethical aim to pass through the sieve of the norm; and (3) the legitimacy of recourse by the norm to the aim whenever the norms leads to impasse in practice

In the section I am working on right now, I am sorting through his ethical interpretations of the prescriptive to think through normative engagement with political contradictions. By prescriptive, he particularly concerns himself with 1). methodological individualism and its assumed split with intersubjectivity and 2). deontology and its baseless anti-teleological rhetorics. In particularly, with regards to UAW 2865’s contradictory stance, normative responses abound in the discourses I am fairly familiar with. Along the line that Ricoeur sketches out for us, three positions are especially salient. In his own words, they are: “setting aside inclination in the sphere of rational will, excluding the treatment of others simply as means in the dialogic sphere, and finally, eliminating utilitarianism in the sphere of institution.” (238)

Law Based On Personal Freedom:

Arguably, analytic moral philosophy, characterized by the exclusion of moral inconsistency through hypothetical thought experiments, is by design averse to contradictions. Debates in the morality of harm, for example, involve various competitive positions demonstrating their relative logical coherence through the rigorous tests of scenarios of harm, such as consequentialism or utilitarianism, contractualism, egalitarianism, etc.. Existing political scenarios are also put under the test of non-contradiction through hypotheticals, for example, the Non-Identity Problem that challenges environmentalist policies, and the Trolley Problem that provides metaphorical distinction between “doing” and “allowing” harms for policy making. This aversion to contradictions motivates normative rational choice theory to devise decision-making models in the face of incommensurables. For instance, Suzumura consistency avoids a money pump in public policy decision-making.

Ricoeur uses Kantianism to illustrate the continuity between an ethics of the good life and a morality of the good life. Despite morality’s differentiation between desire (as trapped in its own teleology) and will (as in relation to the law and thus serving as universal constraint), the boundary between them is quite arbitrary. He puts it concisely, “The style of a morality of obligation can then be characterized by the progressive strategy of placing at a distance, of purifying, of excluding, at the end of which the will that is good without qualification will equal the self-legislating will, in accordance with the supreme principle of autonomy”. (207) In other words, Kantian morality is the impulse to pursuit an unreal and pure recalcitrance, against the empirical impurity of the finite will’s inclinations. A good will without qualification is one in perfect alignment with the universal law. “True obedience,” Ricoeur notes, “is autonomy”. (210) If, according to Kant, the principle of autonomy establishes a synthetic relation between freedom and the law, the autonomous self/person is interchangeable with the law and thus is an end in herself. This creates at least three aporias, Ricoeur argues.

First, if the good will is in synthesis with the law, this becomes a chicken and egg question. Autonomy takes the form of receptivity and becomes inseparable from the latter. To exclude the possibility that the good will itself is motivated by the desire for respect by the law, thereby moved by inclinations, Kant splits affectivity into two: pathological inclinations and reason. But what differentiate inclining-affect from reasoning-affect (the affection of freedom by the law)?

Second, the arbitrary split above ensures that self-esteem passes through “the sieve of the universal and constraining norm—in short, self-esteem under the reign of the law” (215). But if respect is by definition characterized by the autonomy in sharp contrast to passivity, it is structured to be a teleological reflexive conception of morality. If so, what exactly is the difference between teleology and Kantian deontology?

Third, because of the distinguishment between the propensity for evil and the predisposition to good inherent in the conditions of a finite will, Kant seems to suggest a pretty bleak picture of humanity. (216) The fact that the propensity for evil appears at every attempt to formulate maxims, to Kant, is the reason why religion exists: to cleanse evils and restore the control over good principles for freedom. This, Ricoeur suggests, introduces a sort of agnosticism with regards to the goodness of the maxims we follow, “Act solely in accordance with the maxim by which you can wish at the same time that what ought not to be, namely evil, will indeed not exist.” This, to him, points to the necessity of ethics in the constitution of moral norms.

However, going back to the main argument about “the necessity for the ethical aim to pass through the sieve of the norm”. Why, and in order to do what?

Scaling Up Intersubjective Demands:

If moral norms necessarily correspond to the first aspect of Ricoeur’s small ethics, the good life, the dialogic nature of norms relates to the second aspect, solicitude. Ricoeur argues that the affirmation in solicitude “is the hidden soul of the prohibition” of the Golden Rule of “treat others as you would like them to treat you”. (221, 219) To further illustrate the parallel between ethics and morality, he continues through a more indirect argument. In ethics, the good life is closely tied with intersubjective solicitude “at the price of a genuine leap” through which otherness breaks the separation of the ego. He argues that likewise, in morality, autonomy is in close connection with the respect of persons (expressed through normative prohibitions). Insofar as the “others” cannot stay in the form of abstract universal humanity without violating the first maxim of treating each as an end it itself, respect necessarily entails solicitude as its basis. Kant’s maxim of “Act in such a way that the maxim of your will can always hold at the same time as a principle of universal law” is an imperfect formalization insofar as one person’s perspective will not exhaust what others like and/or dislike if it is to be consistent with the Golden Rule. (222) This is also where Ricoeur explicitly critiques the notion of humanity, in the Kantian sense, as an erasure of concrete, plural, and diverse otherness by making the others abstract, singular, and homogenous. (223)

But it is exactly here that he exposes his own complicity: if humanity is designed to cover up the elimination of radical otherness, what would an alternative be if the prohibitive language of law is to be preserved? He seems to have no other answer than to envision a back and forth dialectics between the ethical and the moral, insofar as abolitionism is not on the table. It is really interesting to see how the logic of modernity as necessary evil is smuggled into his ethics-centered arguments. It is a logic of necessity that preemptively exclude any critique of the modern without naturalizing it. Despite his insistence on the primacy of ethics, embedded in this move is his own deep mistrust of visions of the good life, of solicitude, and of senses of justice, that is, of ethics’ capacity to scale up its applicability. But the imperative to “scale up” escape critical investigation here: why does ethics have to scale up, toward what ends? And also, whose ethics are we talking about here? We soon realize that the demand of scaling up is but another name for the transparency thesis under globalization, for which the global is the natural terrain to operate within.

Projections of just institutions:

Ricoeur contrasts the (rudimentary) sense of justice in the distributive sense here with contractualism. He traces the fiction of a founding contract back to the urge to strictly separate the just from the good. This move creates an apparent enigma, in his view, of the legitimate foundation of the republic that supposedly justifies its continuous existence and operation. Since neither Rousseau nor Kant address this enigma directly, but instead mythically (a lawmaker in place or the achievement of civic liberty at the expense of “primitive freedom”), he looks at their more recent inheritor, John Rawls. Ricoeur shows, quite convincingly, that the key motivation behind Rawlsianism is anti-teleology, specifically anti-utilitarianism, in favor of contractualism. It follows, however, that “The Rawlsian theory of justice is without a doubt a deontological theory, in that it is opposed to the teleological approach of utilitarianism, but it is a deontology without a transcendental foundation.” (231) He arrives at a conclusion after a long analysis of Rawls’ formulations of the veil of ignorance and fairness as justice, “this (purely procedural) conception (of justice) provides at best the formalization of a sense of justice that it never ceases to presuppose.” (236)

Subsequently, he makes two observations. “On the one hand, one can show in what sense an attempt to provide a strictly procedural foundation for justice applied to the basic institutions of society carries to its heights the ambition to free the deontological viewpoint of morality from the teleological perspective of ethics. On the other hand, it appears that this attempt also best illustrates the limits of this ambition.” (238) At the end, he seems to make peace with Rawls by echoing the “reflective equilibrium” between the theory and our “considered convictions”. The assumption of the untrustworthiness of senses of justice, however, is never fully justified and explained.

0 notes

Text

what brings joy recently

the smell of my cats

just touching, looking at, and playing with my cats

arc nova

collaging on my journal

walking to mason park and sitting under a tree

spending time chatting and hanging out with my partner

the smell of my incenses

drawing animals and kids

waking up early in the morning

looking at the sand cat in san diego zoo

starting to make progresses in paper

taking care of my plants and see them grow

reading a book quietly

the thoughts of wynter the husky

making jokes with friends who reciprocate

making plan with friends to go to a radical zine workshop

singing in the car

observing the squirrels in the neighborhood

feeling supported by herbal allies

divest from consumption and reinvest in communities

0 notes

Text

Compulsive Temporalization

Recently I have picked up the habits of listening to the Zen Studies Podcast again, not because I am so much of a buddhist or a zen practitioner. Not at all. Quite the opposite, I have an increasingly strong feeling that Buddhism, or most religions for that matter, is part of this pipeline of colonial sanity extraction. Why is it always the case that the saint is a dude in a position of power and privilege? Why is it that white hippies monopolize the whole discursive field of zen, meditation, yoga, love for nature, herbalism, and the list go on? Why do they always have to think about spirituality, awakening, soul work, etc. so hard? Well because they are all so messed up. But then they go ahead and assume the position of authority (in various twisted and self-deceptive forms of not admitting it), subsequently legitimizing their entitlement of mass worship. What if histories of religions are written this way: indigeneity and indigenous Ways of Being were broken and torn apart by coloniality.

Colonizers were then no longer indigenous because of their distorted relationship to land, animal kins, and peoples. They therefore not just spread oppression, violence, disease, and misery, but also spiritual ghosts that haunt everyone on earth, indigenous folks included. At this point, everyone is possessed by the ghost of separability, to the point where they are either used to it or severely penalized by colonizing powers if they dare to resist it by imagining otherwise. Of course, separability is torturing, and the colonizer experiences it as such as well. But their privileged position allows them to explore and practice ways of relating otherwise without receiving any injuries. And some of them did, mostly in a way that divorced spirituality from materiality, often time compulsively so, because they can’t afford the breaking down of the very system of injustice that allows them to do that kind of spiritual work. My preliminary thought is that coloniality is expressed, in the symbolic realm, as the subordination of the spatial under the temporal. Both the circular temporality of dynastic/buddhist time and the linear progression of modernity are devices for avoiding talking about spatial relationality. But more thoughts to come later.

0 notes

Text

Notes on the Narrative Self

The main theme in my current paper project is thinking through the phenomenon of “contradiction” in political actions through and beyond various interpretations of it provided by the existing literature. Inspired by French theorist Paul Ricoeur, I demonstrate how three main approaches to “contradiction” in contemporary political theory: descriptive, normative, and narrative, are similarly driven by the fear of incoherency and the desire to overcome contradictions. However, while Ricoeur is insightful in his critique of the former two, his own narrative gesturing does not provide a satisfying answer to how one should understand contradictions in her own actions. Its desire to resolve them is a coping mechanism, which is itself filled with contradictions while promising too much. The limitations of fear-fueled theories manifest themselves in their inability to stay in and with contradictions, as I illustrate in the case of trade unionism in the US today. Simply put, a fearful interpretation seeks to immediately sublate contradictions and functions as a shield protecting the interpretor from the loss of (modern) subjectivity. By thus showing the affective underpinning of political theorization, I follow black and indigenous theorists Denise da Silva and Vanessa De Oliveira Andreotti’s insights that the modern Subject is by definition contradictory. Their work interrupts the illusory alignment between ethics, morality, and justice in the (albeit diverse) narratives of modern political theory. Building on the above, I offer a fourth approach of “unstorying the self” to challenge the “transparency thesis” of the modern Subject and interpret contradictions-in-action, in order to hold space for expanding the affective capacity of theory, Ricoeur’s and beyond.

This morning I listened to the episode “Practicing New Worlds in a Time of Collapse” in the show “Movement Memos”, in which Kelly Hayes interviews Andrea Ritchie. Both of them are good examples of what a “community organizer” looks like nowadays, half a century after Alinsky’s professionalization movement. For some reasons, I find myself echo with 90% of what they said intellectually, but only 20% of the affective forces behind the speech make sense to me. I wonder why, after all the discussions of how our current moment is urgent and beyond reform, how experiments are necessary for collectively thinking a way out beyond what we’ve tried that got us here, and how all our struggles are deeply connected across the globe, the messages do not land in audience like me, who care deeply about all these. Perhaps something about the label “organizer” is really troubling. At the beginning of the episode Andrea cites Joanna Macy’s World as Lover, World as Self, in her discussion of what “organizing” means to her nowadays:

“From the ecological perspective, all open systems — be they cells or organisms, cedars or swamps — are seen to be self-organizing. They don’t require any external or superior agency to regulate them, any more than your liver or an apple tree needs direction on how to function. In other words, order, or dynamic self-organizing, is integral to life. This contrasts with the hierarchical worldview that dominated our mainstream assumptions for millennia, where mind is set above nature and where order is assumed to be imposed from above on otherwise random stuff.”

It is this narrative of the ecological perspective that I have an ambiguous feeling about. At the end of the day, if the modern Subject relies on narratives of autonomy, how is this not a cruel optimist resubscription to the same doctrine? Knowing for a fact that both of them work in the NGO industrial complex for many years, it is hard not to make connection to Occupation: Organizer’s critique of the institutionalization of social movements and the professionalization of organizing work on the past decades. It all comes down to the transparency thesis of assuming a position of speech and eventually forming an attachment to theories, stories, narratives, etc. that affirm one’s identity and autonomy. This is something that modernity really rewards and produces. We don’t have to legitimize apple trees by saying they have agency too.

This is why in today’s collage, I wrote “today we world-make with our allies for a university in which smart and pretty speeches are irrelevant, only concrete fights & relational work toward liberation are.” We are in these institutions that reduce our being to what we say, and slowly habituate our sense of pride, ownership, and identification over stories. The danger of this is politics become an infinite language game. Whoever controls language controls politics, and words lose their meanings extremely quickly.

0 notes

Text

The Job Is Not the Work

Today I really just envision doing the minimum of the academic job without seeing it as my “work”. The job in the university, according to Vanessa De Oliveira Andreotti in her workshop on the book Hospicing Modernity, enables the work. This way of instrumentalizing academia allows me a sense of relief. It temporarily liberates me from the pressure to produce, with unreasonable expectations both qualitatively and quantitatively. Hospice work means that I no longer identify myself and my worth with the universities I go to, academic papers I write, the grants I apply to, the journal I submit to, colleagues’ comments, and the conference I go to. It is essentially a divestment of energy, attachment, resources, time, and value from higher edu institutions without resentment and the crave for control. Hospice work is abolition work, adding both an acknowledgement of the inevitability of death and deep care in the form of pedagogical pacing to the latter. We recognize that the stories that “dance with us”, which sustain modernity, are dying along with parts of us. If we keep holding on to it the death process will become extraordinarily and unnecessarily painful. The “academic work” that I do is to carve out a space for sobriety, discernment, maturity, and responsibility, in order to understand the specific stories that drive us to work for modernity. How can we do the job at the bare minimum without the drive to work?

I created this collage (in the left above) in the morning out of an impulse to unstuck myself. At the bottom right I wrote, “today I envision the possibility of hospice work that assist with the death of academia as we know it”. When we prepare for our loved ones’ passing, before and after they cross the bridges, we understand that we hold on to their lives as much as (or perhaps even more than) they do themselves. Whereas Denise da Silva (whose red portrait is juxtaposed next to the text) talks about “the world as we know it”, this death work happens against the backdrop of an entangled world instead of a world of separability:

“What if, instead of the Ordered World, we could image The World as Plenum, an infinite composition in which each existant’s singularity is contingent upon its becoming one possible expression of all the other existants, with which it is entangled beyond space and time…[space-time] which is also a recomposition of everything else…not as separate forms relating through the mediation of forces, but rather as singular expressions of each and every other extant as well as of the entangled whole in/as which they exist?” —Denise Ferreira da Silva, On Difference without Separability

This is why, wether we consciously acknowledge it or not, we are scared of the death of others and the world as we know it. In the case of academia, we are scared that the university no long exists because for so many years of our life it symbolizes intellectual achievements, individual worthiness, and points of normative reference. This fear drives us to work for it, to be unfree. This is why I keep going back to Nina Simone, who embodies the body space, the channeling of otherness, the living in flexibility and fluidity, and her powerful answer to the question “what is freedom”. “I’ll tell you what freedom is to me, no fear. I mean really, no fear!” Next to her is the Nine Colored Deer, a mythical animal figure that responds to the call for help from a drowning person, immediately jumping into the river to save him. It is the lack of fear and hesitance in her actions that I want to keep at the center to remind myself what an image of liberation looks like.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paper as Ceremony, Hospice, and Abolition

All memes below are from the Instagram account @softcore_trauma by Margeaux Feldman, they have great trauma-informed political education content!

I’d like to think of the process of writing an academic paper as transcription for people who have difficulties seeing and witnessing what folks in the struggles have been trying to convey to them. It is a tedious thankless labor because I have to pay to get it presented in conferences, allow it to become property of the publishers who think they own the world, and risk being tuned out at anytime if anything I said make them feel “uncomfortable”. Their spiritual hell is contagious. Welp. It is really overwhelming and challenging sometimes, not intellectually, but psychologically. I often find myself experiencing stages of post-traumatic affects: flashbacks, impulses, rage, self-doubt, and/or the deep inability to grieve and let go of the lingering attachment to a genuine audience with relational maturity. No, this is a job that requires me to talk to epistemic abusers. And yes, it is fucking traumatic and traumatizing. And these are such identical feelings I have in engaging with academia writ large, UAW region 6, and cis male-led social movement spaces.

What does “activist scholarship” mean anyways? How are they conceptually two separate things? Is there a way to do research that doesn’t feel like a complete betrayal of who I am? Or is this whole academia thing just for the job? Where is my “pipeline”, if it’s neither academia nor the non-profit industrial complex? I found academic white anarchists or radicals’ advice unhelpful for thinking about these questions. And I don’t think, however much I might be willing to conform to the norms of academia or fraternity unionism, I would ever get a job in either places as an “alien” anyway. And once again I went back to Shawn Wilson’s book, Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods, in which he notes:

“……Indigenous research is a ceremony and must be respected as such. A ceremony, according to Minnecunju Elder Lionel Kinunwa, is not just the period at the end of the sentence. It is the required process and preparation that happens long before the event. It is, in Atkinson’s translation, dadirri, the many ways and forms and levels of listening. It is, in Martin’s terminology, Ways of Knowing, Ways of Being, and Ways of Doing. It is the knowing and respectful reinforcement that all things are related and connected. It is the voices from our ancestors that tell us when it is right and when it is not. Indigenous research is a life changing ceremony.” (61)

But then parts of me seem to be asking, why is it that I feel so hesitant to write down what I think? Why is it so damn hard to write academically comparing to writing for the movement or for my personal journals? If it is just a ceremony it would clearly be easier? This leads me to think that maybe a ceremony of “what is” has to come after the hospice work for “what was”. It is when I imagine an academic audience sitting in front of me that the traumatic flashbacks happen. This audience does not have to be overly harsh at all, they can be resonating with whatever I present but still give me a deep sense of shame. Maybe they are just me, and maybe I am socialized into this overly critical view towards myself and my own works. And this might be the part where hospicing comes in. The individuality, the fear, the pride combined with low self-esteem, the unknown rules of the academic game, the willing player, the gatekeeping gazes. Clarity to the world I want to see is confusion to the world I will hospice, and that creates immense difficulty and even impossibility for the writer in me. I do think this feeling that I don’t know how to position myself and my own work plays a big part in my academic stagnation. After abandoning the position of a fearful and self-loathing graduate student, I have sunken into the liminal space of cynicism and disengagement for a long time. The lack of motivation is surely a tricky thing to navigate in life, especially when pragmatic reasons force you to do something. It at least seems like finishing the degree would be the most pragmatic thing to do, but then I should be cautious about rationalizing this pragmatic goal through creating some rationale for it. The impulse to refuse a purely instrumental view of academic writing is perhaps the source of my struggle. Maybe it is just for the job, for the degree, and for the visa. I mean, what kind of ultimate meaning would a worker find in her tedious repetitive labor? Should she? The fact that we think academic work is so much different from factory manual labor is kind of ridiculous. This momentarily reminds me of the poems by Xu Lizhi, extremely powerful and sad, punching a unmendable hole on the wall of hope. How is life livable if hope is lost?

Maybe even before hospice work, we need to think about academic work as traumatic and traumatizing. We are expected to create knowledge out of a vacuum, to allow the tokenization of our bodies, to be deprived of our souls so that we can be the zombies of publishing, to continuously be the supplier of words for the market, to divorce ourselves from communities so that we will be accepted by authorities, to be different, to stand out, to perform. To talk about healing is a betrayal to those getting a slap in the face every second by reality. I do not want to play this game called academia, maybe admitting this is the first step to write the paper, to hospice modernity. Academia itself is the drug, and our addiction looks like the constant oscillation between hyperarousal and hypoarousal. We are either high on the substance, along with all the fame, achievement, recognition, praises, rewards, congratulations, and adrenaline-driven work ethics, or in desperate need to use it, in a state of anxiety, fear, despair, emptiness, uncertainty, shame, self-doubt, self-blame, cynicism, and more. And maybe we relapse, or we quit in extreme distress. With this, perhaps the first thing to do to shift our view of academic research is to abolish academia as we know it.

0 notes

Text

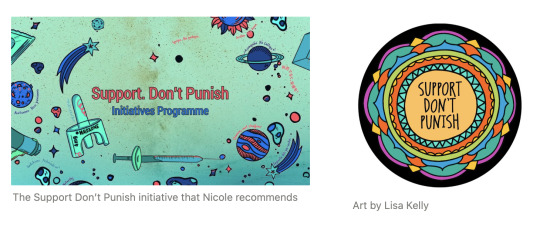

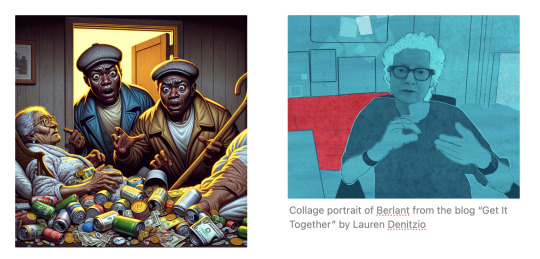

The Depressive Realism of Addiction

Today’s podcast is, again, from Frontline Herbalism, an episode in which Nicole interviews her partner Rob about his experience of and thoughts about substance addiction. While I have known some advocacy for decriminalizing drug use in North America, Nicole is right that there is not much organizing around addiction, especially as a public health issue, in social movement spaces. This makes me into wondering if and to what extent “organizing” itself is narcotic, as well as how modernity-coloniality relies heavily on addiction-based affective structures to operate. But before it goes too far, I want to take notes on a couple things they discussed that are important.

First, being addicted to substance, especially in the current society that stigmatizes, infantilizes, criminalizes, and dehumanizes addicts, is extremely traumatic. Such trauma is disproportionate, considering other completely normalized forms of addiction, such as work, heteronormativity, ableism, standardized body image, meritocracy, hierarchy, capital, consumption, screen time, toxic positivity, etc., because the way modernity deprives societies of their medical sovereignty. It is particularly hard to maintain any kind of relationship with the world, such as medical professionals and schools, not to mention building and sustaining close communities of friends and family. Even those who built a bond among themselves often lose members to incarceration, sudden death, and/or displacement. In addition to this, the amount of anxiety produced by the unpredictability of the dosage and components of the drugs they get each day is insane. A big part of the high rate of relapse among addicts is exactly this traumatic experience and the sense of pain and isolation it induces, which drives them to seek more solace from substances.

Second, it takes coordinated social support to help, which in and of itself should be a political campaign. It is not easy to “come clean” once you are addicted to substance and forced to live on the street in the current society. On the street, drug addicts usually need to work extra hard to fund their habit via risky choices, a reality that Rob describes as a “full time job”. In such circumstances, community detox cannot happen. Only when there are funded infrastructures providing safe and free drug use and temporary staying spaces, as well as resourceful communities coming together to help individuals in need of healing and recovery, would the whole weaning off process be likely to succeed.

Third, drug addiction should be framed, thought of, and treated as a disease instead of a moral failure. At the end of the episode Rob corrected the language of “enabling”, as addicts don’t need drug dealers to “wave it” in front of them, they would seek it out themselves. By using such language, the society encourages the deprivation of substance from addicts as the ultimate solution, whereas in reality it could be deadly and immensely traumatic to them. Instead, addiction is a condition of sickness that manifests in substance abuse, the latter of which is the symptom not the cause.

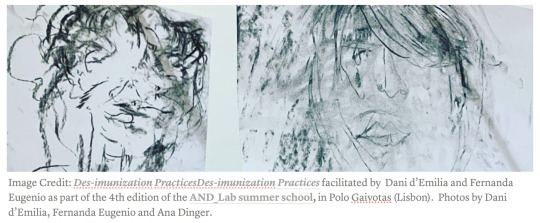

I find addiction extremely generative for thinking about modern-colonial affect, not as a metaphor, but as a description. What if modernity-coloniality is a form of addiction, the forms of substance of which, as Rob points out, do not really matter. As I mentioned above, this could be work, heteronormativity, ableism, standardized body image, meritocracy, hierarchy, capital, consumption, screen time, toxic positivity, information, professionalism and authority, commodities, etc.. The objects can shift and change, but addiction per se is the disease left untreated. This helps formulate a loving critique of Lauren Berlant’s discussion of cruel optimism that limits itself in the confine of “American dream”’s brutal awakening: it’s not even timely, but applicable to modern-coloniality at all times. In the first chapter of Cruel Optimism she offers an interpretation of Charles Johnson’s Exchange Value that has stuck with me for a couple years. The story is about two black brothers, who grew up in poverty, robbing their possibly dead neighbor, ending up with a giant amount of money. They each approach this very differently, one through binge consumption, the other compulsive hoarding. She comments, in her usual style of depressive realism, on page 41,