Photo

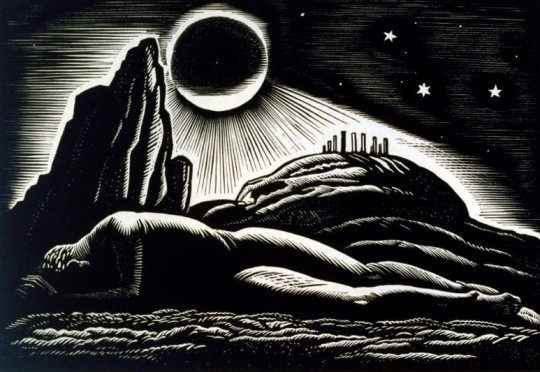

Night & Gold

When I first pondered blogging, I mistakenly believed that Tumblr blog names needed to be one-of-a-kind, as, say, domain names do. (It was the first of many Tumblr red herrings.) I wanted the name to refer generally to the interplay of darkness and light, long a preoccupation of mine, as a way of unifying many of the other interests I hoped to explore—art, design, and architecture; literature, poetry, and philosophy; nature and landscapes; cities; even politics. But nearly every blog name I came up with was already being used.

Then I remembered two companion choral works that overtly refer to light and darkness. The first, Eric Whitacre’s Lux Aurumque (Light and Gold) bathes us in the tranquil golden light of the Nativity. It’s a justly iconic work in its repertoire, setting just a few lines of by Edward Esch, translated in turn into Latin by another poet, Charles Anthony Silvestri. Within a few minutes, Whitacre’s pacing, harmonies, and sonorities cast a spell both cosmic and profoundly intimate.

[ Listen to Lux Aurumque here. ]

The second work, also Whitacre’s, is worldlier (except for its reference to angels, one of whom “…dreams of sunrise, / And war”) and explores the darkness of gold, not its radiance. In Nox Aurumque (Night and Gold), shadows, sleep, and death enshroud light; war and tears dull the gilded metal of weaponry.

If Lux Aurumque is iconic and spellbinding, Nox Aurumque is eccentric and even primal. When I first heard it, I was reminded by choral music of the Latin American Baroque—works in the cathedral style familiar to Spanish colonists but retaining some of the visceral soulfulness of the colonized. Nox Aurumque is by far the least performed, but of the two it’s my favorite. It sets four stanzas by Silvestri, who wrote them originally in Latin with an ear to the lingual sonorities he knew the composer would exploit. In his program note, he confesses to having “to settle at times for some Latin that strayed from what Cicero would have written.”

[ Listen to Nox Aurumque here. ]

This blog’s title is taken from the last line of the final stanza:

Aurum,

Canens alarum,

Canens umbrarum.

Gold,

Singing of wings,

Singing of shadows.

Google translates canens umbrarum as “shades of gray”—not quite what I had in mind but perhaps also fitting.

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

short trip home (part 2—west of the divide & back)

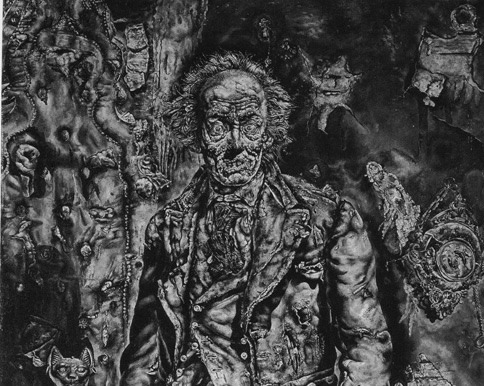

Two famous movies produced before Technicolor became standard, when it remained costly and labor-intensive—The Wizard of Oz (1939) and The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945)—still made strategic limited use of it: in Oz (at length) as the vivid dyes rendering Dorothy’s polychrome dreamland; in Gray as the jolt bringing us face-to-face with Dorian’s corruption and cruelty.

Audiovisual entertainments are now so immersive and realistic that it’s hard to gauge what impact the selective use of color once may have had on movie audiences familiar only with black-and-white. Yet both films’ technique came to mind as I drove from east to west over Rogers Pass—from dry, late icebound winter into full-blown mountain spring. I weighed switching to color for the second half of this post.

That would have strained an already slight parallel. But the greens of the meadows and forest floors along the Blackfoot Valley did rival the John-Deere-tractor hue of the Wicked Witch of the West’s face. And the unidentifiable roadkill emerging here and there from the ditches’ receding snows could have resembled (since it was already on my mind) Dorian’s vile portrait-corpse.

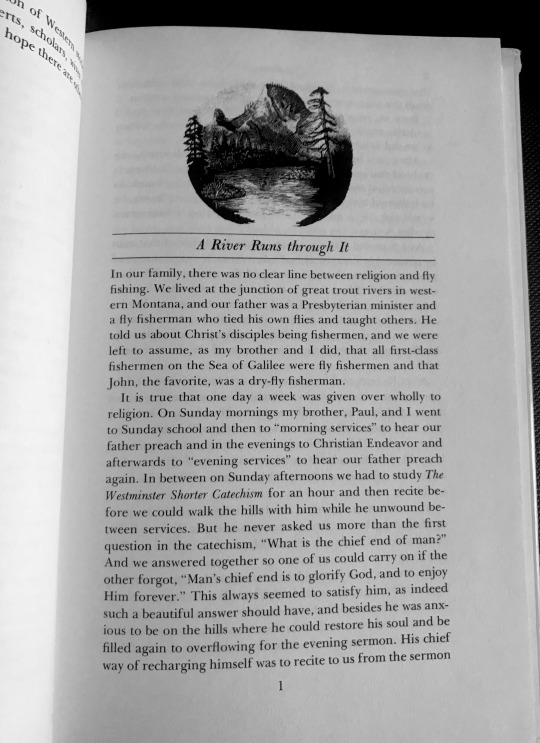

The Blackfoot Valley has less idiosyncratic ties to cinema with Robert Redford’s A River Runs Through It (1992), the movie based on the title novella of an autobiographical collection by Norman Maclean, a retired Shakespeare professor from the University of Chicago, who had grown up in Missoula. The film doesn’t come close to conveying the story’s wonder and laconic pathos, I’ve always thought. The collection, never promoted, and published by an academic press since no commercial publisher would touch it, was in my teens a dog-eared parable passed around among fly-fishing family and friends, who took it to heart before it grew widely famous (although my paternal grandfather, an ardent fly-fisherman and churchgoer, like the author’s father, found it scandalous).

The Big Blackfoot River comprises the healing waters that course through the story, though other streams make appearances too. The Blackfoot is “multitudinous,” “gossamer,” “electrically charged,” and above all “beautiful”: a bestower of glory and haloes; a shadow-maze, an oracle, a cipher. It’s the timeless current that recalls for Maclean his brother, Paul, and helps him come to terms, imperfectly, with Paul’s bewildering character and at last his murder.

The North Fork of the Blackfoot River (web photo)

In July and August, the Blackfoot pours like molten crystal through long, at times suddenly sharp, curves, tinged emerald in its channels and holes. But in mid-May this year it raged down in such muddy volume that its rapids’ usual din fell to a whisper—an unnerving sign of power and mass—and it flooded flatter parts of the valley floor in shining swaths. I wondered how the fabled trout within it were surviving such forces.

At various points, Highway 200 and the river diverge, to cross again miles further down. At each successive crossing that day its torrent seemed doubled. Near the sawmill and railroad town of Bonner, where the Blackfoot joins with the Clark Fork River, it ran as wild and full as I could have imagined possible for the river I had known since childhood.

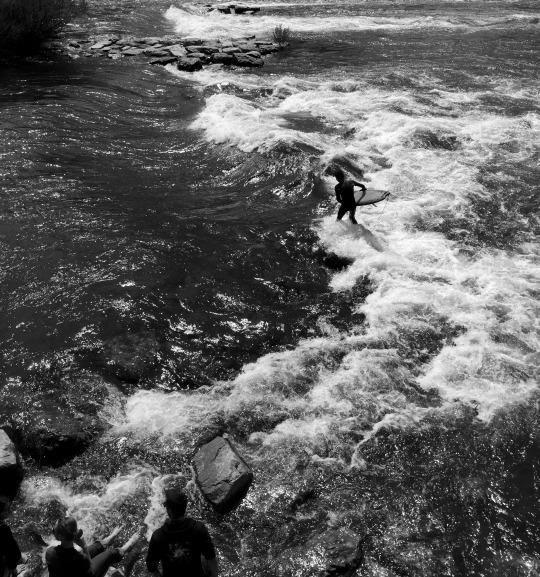

A few miles yet further down, in Missoula, the Clark Fork surged too. As its banks bloomed obliviously with lilac and chokecherry, the river smashed through town at 100-year flood levels, completely drowning Brennan’s Wave, the white-water hydraulic there beloved of kaykers and river surfers. Norman Maclean’s Blackfoot had here become T.S. Eliot’s strong brown god —“sullen, untamed, and intractable.”

The Clark Fork River in Missoula May 2018

Brennan’s Wave in May a few years ago

Most of the city itself hadn’t flooded, though, and bustled with the business of graduation, taking note of the Clark Fork’s maelstrom from its bridges but preoccupied with its own rhythms and rituals.

Indeed nearly all weekend the weather and setting were paradisal. The crabapples’ white profusion disappeared here and there into the snows of the Missoula Valley’s five surrounding mountain ranges. Lawns and trees pulsed green in long spring light. There were parties for the graduates and their families, smiles and toasts and a palpable sense of relief. The student house where my nephew lived stood just a block west of the campus, a neighborhood that includes beautiful yards and small mansions of various architectural inspiration.

Charles C. Brothers Residence under restoration

Missoula embraces its identity as a political and civic oasis in a deep red state, still retaining some air of the working-class progressivism forged through its early ties to the railroads, timber industry, and Forest Service. The university, of course, has long reinforced this culture on its own terms, as do Patagonia-wearing millionaires who’ve moved there for close access to wilderness. The city itself has bucked the regressive zoning and land-use trends elsewhere in Montana to restrict sprawl and keep the bare foothills cradling it mostly development-free. Those foothills constantly draw the gaze upward and shift with clouds and light; from the busy center of town their emptiness somehow calms the heart.

Alley art downtown

Alchemy along the walls at Butterfly Herbs

In Missoula, on the south bank of the Clark Fork

Missoula cherishes its oddities, too, human and otherwise—probably none moreso than the dramatis personae haunting the Smead-Simons building, Montana’s first skyscraper, known as the Wilma. Standing tall on the downtown-side bank of the Clark Fork, the building’s early history (available in various accounts) revolves mainly around its opulent movie theater and the Crystal Plunge, an indoor Olympic-size pool (another Montana first). Through the years chapters featuring a perfumed fountain, Mahalia Jackson, ornithomania, and David Lynch were added. Its apotheosis was the Chapel of the Dove, a shrine assembled in its basement to venerate Korro Hatto, the beloved pet pigeon of longtime Wilma owner Eddie Sharp.

Though openly gay (when being so in the American West carried serious risk) and half her age, Sharp had married Edna Simons (née Wilma), the widow of the the Wilma’s founding owner and a former Vaudeville singer. Sharp revered and dearly loved her. According to Missoulians I know, but no written account I could find, Sharp came recognize Korro Hatto as Edna Simons-Sharp’s reincarnation at some point after her death in 1954; the chapel was an exact replica of chapel where they had married four years earlier in New York City. Korro Hatto, Sharp��s constant shoulder-perching companion, lived to the age of twenty, and they are interred together, along with Sharp’s subsequent partner of forty years, Robert Sias, in Missoula City Cemetery.

Missoula is now home to several start-up breweries and distilleries, but still hosts a number of its original taverns, most notable (to me, anyway), the Oxford—”the Ox”—whose blackjack tables never close and which used to serve brains and eggs as part of its 24-hour breakfast menu. The poet Richard Hugo, perhaps besides Maclean the most famous literary figure who lived and taught in Missoula, drank and socialized here and in the town’s numerous other “cavelike, majestically slow-moving Western barrooms.”

Stars are not in reach. We touch each other

by forgetting stars in taverns, and we know

the next man when we overhear his grief. Call the heavens

cancerous for laughs, and pterodactyls clown

deep in that fragmented blue. In that red heart

a world is beating counter to the world.

Soon enough, It was time to drive back, to cross the Divide again in my rental car (which my youngest nephews, twins, relentlessly deemed “gutless”)—this time from west to east. The flight home to Minnesota would depart the next morning at a harsh pre-dawn hour.

After goodbyes, we headed out in a caravan. I did so with a heavy heart—the weekend had been too short, the family time joyous but jumbled, the fragrant sliver of springtime achingly perfect.

The road from Missoula to Great Falls is still beautiful, though the views eventually resolve, once over Rogers Pass, into the forlornness of eastern Montana. The late afternoon sun, falling behind us, kept out of our eyes and lit the shifting landscapes ahead. The Blackfork River dwindled as we climbed, at first only slightly, but by Lincoln decidedly. The snows on pass had mostly melted away.

We sped through Lewis and Clark and Cascade counties, past ranches and windbreaks and homemade antigovernment signs nailed to fenceposts, anxious for our destination. At Vaughn, though, rather than taking the interstate where it crosses highway 200, we cut off on the road leading to First People’s Buffalo Jump State Park, or the Ulm pishkun as it’s locally known. The twilit hills and coulees glowed pink and gold. We stopped and got out of the car at the turnoff to McIver Road just to take in the sunset for a few minutes, then got back in and drove the rest of the way to my brother’s house before dark.

#montana#norman maclean#eastern montana#missoula#lewis and clark#brennans wave#A River Runs Through It#first peoples buffalo jump#richard hugo#charles c brothers residence#the wizard of oz#dorian gray

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

short trip home (part 1—east of the divide)

The ties I have to my home state of Montana are akin to its extremes and as complex as its landscapes. But for the most part they are grounded still in belonging and love.

One summer, I was driving with a friend one through the Judith Basin area, along Highway 427, which runs from Raynesford into the Highwood Mountains. It was just before twilight and we might have been the only car on the road’s twelve-mile length, a shortcut of sorts winding upward through dry foothills until huddles of poplar and juniper gradually signal the transition to higher, snowfed elevations. A native of Ohio and lover of New England, he was spooked by the land’s sheer nudity—rolling miles of shortgrass interrupted occasionally by yucca and split-rail fences—but seemed all the same consoled that such places still exist. “You came from here?” was the subtext of his silences.

I had been a somewhat alienated, inwardly meandering (if solicitous) Montana boy (in other words, alienated mostly from myself), and it is not over-simple to say that one of the few cures for my abstractions and furies then was to roam physically and imaginatively into these forbidding expanses and, even more restoratively, into the seams between them—the coulees, creekbeds, oases, and canyons where the expanses had cracked apart and over millennia been jaggedly stitched back together.

Last weekend, I flew to my hometown for a nephew’s graduation. The plan was for the family to gather at my brother and sister-in-law’s, then drive together to Missoula. But there were flight delays, and I found myself contemplating the three-hour drive over the Continental Divide well after dark alone. It would have been foolhardy to make the trip but I was game. As luck would have it, I found my cousin Kory waiting for his wife, Gay, as I walked to get a rental car; I hadn’t realized she’d been on the plane.

They kindly insisted I stay the night with them. Kory, Gay, their son, and his parents live on McIver Ranch, about 5 miles outside of Great Falls, which was homesteaded by his and my great-grandfather. I love returning there whenever I can.

Early the following morning, after coffee with my relatives and a walkaround, I headed out, first northwest along McIver Road, then through Vaughn, Montana (founded by Robert Vaughn, another ancestor and my namesake).

West of Vaughn, highway 200 begins, jutting off just before a string of three little towns, Sun River, Fort Shaw, and Simms. The road leading from Simms over Rogers Pass to Lincoln is one of my favorite drives on earth. It’s not spectacular in the usual sense of the word, but it haunts me to the bone and exudes a deadpan grandeur.

Crown Butte

The Dearborn River, swollen with snowmelt, where joined by its middle fork

Abandoned General Store in Fort Shaw

Eventually, as one hurtles along at 80 mph, as Montanans are wont to do, the great sweeps that characterize this part of the eastern Rocky Mountain Front give way suddenly to steep stands of Douglas fir, and the climb to Rogers Pass begins. An unassuming high-point as mountain passes in Montana go, it’s most famous for registering −70 °F, the lowest-ever recorded temperature in the contiguous United States, in 1954. It also marks a passage over the Continental Divide, implacable arbiter of countless distinctions in landscape, vegetation, weather, drainage, and people between its eastern and western sides, and far beyond.

That day, deep May snow lay mostly along the east, where deciduous trees and bushes remained unbudded and the ice locked in place except for trickles. Just on the other side, though, spring rampaged as if encountered in time-lapse. The greens deepened, migrating birds swirled, and Pass Creek, a headwater of the famed Blackfoot River, plunged down its rocky chute in muddy white rapids. Pretty soon on the descent there were chokecherries in blossom and tottering calves next to their mothers in the fenced clearings beside the road.

11 notes

·

View notes