In some accents of English “pacts��� and “pax” are homophones.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Random Notes: Nationality and the Second Civil War

I may or may not have just realized that it would make sense for the Second Civil War to be at least partially caused by nationalism.

Nationalism in the sense I mean is like that in the failed European revolutions of 1848: wanting to redivide political boundaries based on ethnic ones.

Novanity didn't start out with ethnic lines, or ethnicities at all. Among humanity, these had mostly just kind of dissolved, setting aside the heritage languages, in the melting pot of the Grand Voyager and then the Moon. Humanity in Scientia thought of itself first and foremost as that, humanity in Scientia. Physical differences were irrelevant (and still a touchy subject, given that racism on Earth had yet to completely die away), linguistic differences were mostly smoothed out by the universal Esperanto, and cultural differences were seen as cool but not internally divisive.

When the Novan Creation Period began, the concept of an ethnicity was still mostly remembered and understood (the definition I mean here being specifically a regional cultural difference rather than one just about someone's or their ancestors' physical origin), but they did not apply whatsoever to the tabula rasa novan species.

By the Departure, they had pretty much been entirely forgotten, and the novans left behind hadn't been settled wherever they were long enough to develop distinct ethnicities. There were regional cultures, yes, but these were more along the lines of the differences between Denver and Pittsburgh in the United States. Denverites and Yinzers are culturally distinct, yes, but they don't have the ancient continuities of characteristics and lore and cultural developments that create an ethnicity.

They didn't develop them in the War Era, though distinct regional cultural traditions took root and the first recorded folklore dates from this period. Here there was identification with the political body of one's residence, but not a sense of inherent, like, deep-seated difference between, say, a resident of Putiya Nakaram and one of Aŭsel. PN and Aŭsel, if ever they bordered each other, could have traded chunks of territory without the residents of those territories being up in arms because they were ethnic Aŭselites being abandoned by their nation. They would have been pissed instead about the stricter inspections and the diametrically opposed foreign policy.

The early Imperium tried to unite itself as one novan species, and the worldwide novan identity crisis helped this along, basically making novanity an overarching ethnicity uniting all others. This was pretty universal, though it did manifest differently in the governorates than in, say, highly liberal Putiya Nakaram the city (yes, yes, "New City the city...").

Although an East-Northerner and a West-Southerner (or especially a West-Northerner and a West-Southerner) would identify themselves as from different places, possibly quite vehemently, the division had not risen to the level of ethnicity. If a West-Southern family moved to the West-North and its children lost their accents, they would be accepted fully as West-Northern, and there would not really be much cultural adaptation for them to do.

The First Civil War, four hundred years into the Imperium, exploded because of political problems between the governments of various ŝtatoj, which wanted to retain their ancient rights and privileges, and the Imperium, which wanted to rationalize its subsidiary governments and had kind of a boneheaded emperor at the helm.

I tentatively pin down the development of ethnicities in the Imperium to the inter-civil-war period, where four to seven hundred years have passed in which the peoples of, say, the area around the Storm Ocean (probably especially the Dodossan Archipelago, Ĉinĝuĉun, and the Saber) sat around in the same place, mingling and developing a sense of their common ancestry and their distinctness as a culture, which then turned into a sense of their distinctness as a people.

Ta-da, my friends, we have created an ethnicity.

So, obviously ethnicities and nationalism have started a fuck-ton of wars. For the most part, I think stark divisions between them are counterproductive and unrealistic. They lead to tribalism that in turn leads to us-versus-them or ingroup/outgroup thinking, which leads then quite naturally to oppression, and some of their current manifestations in mainstream American politics are abhorrent.

But I'm not here to talk about any of that. I'm here for space cat people, and weirdly the failed revolutions of 1848, which I have recently been down a mild rabbit hole on.

So, 1848 in the Austrian Empire and what is approximately modern Germany was defined by nationalism, here meaning a desire to unite one broad category of people (an ethnicity) into one country. The approximately-modern-Germany region was trying to unite itself (and the Czechs, who were inside it in Bohemia, were trying to break out, like the non-Germans in the Austrian Empire); it was in the aftermath of the Holy Roman Empire and it was a convoluted mess of different little polities. The Austrian Empire included modern Italy, Hungary, and Croatia, among others, and these groups tried to break free along ethnic lines and form their own independent or internally autonomous nation-states. These were all under German (...Austro-German?) hegemony.

The Austrian Empire case is roughly what the Imperium would have going on.

Now, obviously in reality people mix and that prevents the creation of clean borders. For an 1848 example, look at Slesvig-Holstein: legally bound up together, identifying more with each other than with the larger ethnicities (Dane and German) trying to claim them, refusing to be separated.

But if you're part of an ethnicity that is not represented in the ruling classes, and you and the people around you think you're not being well served by that ethnically-something-else government, you're more liable to go into revolt claiming your distinctness as a nation as your justification. You're going to imagine a world in which you and your ethnicity decide things for themselves, clean border lines tbd later on once you've got your independence.

You also may have strong conflicts with the ethnicities around you, which you see as different and possibly have fun things like long-running border feuds with. Or butter side up, butter side down; could be that.

It's a strong motivator.

And it's the kind of thing a competent novan administration, which they do have in place, could miss. Novanity has never had a concept of nationalism before, really; they didn't have ethnicities to divide their imagined ideal world on. It's an out-of-left-field threat, and one the ruling class might think they don't have to take seriously.

And it could send the people of a bunch of ŝtatoj up into revolt, and possibly create something like a Provisional Archipelagic Republic composed of the Dodossa and Ĉinĝuĉun' or something and that would just be really fun.

Triple and it makes the cadets an outsider ethnicity rather than just a too-loyal fifth column, which I won't ramble on about here but which is fascinating in its implications.

-----

So this was all written at a worrying hour of the morning, having had an epiphany after waking up in the middle of the night. The writing quality isn't up to snuff and I may reconsider it all tomorrow, but for now these are my thoughts.

0 notes

Text

I have a Reddit, so help me God.

u/novanhistorian, naturally; probably going to be mostly or exclusively active on r/worldbuilding and r/conlangs, the latter for non-Imperium-related projects.

I’ve been sitting on the account for a bit, but started responding to things on r/worldbuilding today with targeted essays that I'll probably clean up and post over here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The 800-people initial human population size is probably going to get retconned significantly up. I’ve been reconsidering it for a while and have now received outside input which agrees with the reconsideration. This may alter the population explosion timeframe, which will alter what you’ve read, which is the deep backstory of the Imperium Novel.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Damn it, I missed the Imperium Novel’s anniversary again. All of this started on the twenty-fifth of May, 2020.

I know the date for certain because the first thing I ever wrote was a song in a Google Doc idealizing Memphis, Tennessee, sung by early-development Sana Staravia (spelt that way then) to Memphis Mylera when they were growing up. I wrote it on the evening after the one-shot daydream I wanted a flat villain for that the Imperium then spiraled out of, because the idea just wouldn’t leave me.

The Google Doc was titled “MGTDS Songs,” MGTDS coming from “Memphis Goes to the Dark Side,” and the rudiments-of-a-novel that I soon started writing became “MGTDS Proper.”

We are now five years, a scrapping of the original attempt, and several major revisions to the world later, and MGTDS is still the development title of the main novel of the Second Civil War.

Enjoy this ancient history. My raison d’etre is now five years old.

#🗃️ administrivia#oh god the early MGTDS was weird#Memphis had these bizarre theories of morality#like imprisoning your better self in a literal birdcage

0 notes

Text

A Sketch of History

Just a table of contents.

Human Future History (21st through 23rd centuries), 2.3k words

The Pre-Novan Lunar Period (2300 to 2450), 4.5k words

The Moon’s Favorite Electrician (2450 to 2320), 4.5k words

The High Human Tenure (2320 to 2600), 3.7k words

The Population Explodes (2600 to 2680), 3.5k words

The Third Academy (2680 to 2731), 3.5k words

Still to be written, and likely to expand into several pieces, are:

The War Era (2741 to 2983 human calendar and -233 to 0 Imperial calendar), _._k words

The Imperium through Now (0 past 750), _._k words

Addenda:

The Three Worlds, 1.5k words.

The Butchering of Russian, Otherwise Known as the Birth of Parrus’, 1.3k words

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Moon’s Favorite Electrician, 2450 to 2520

AKA “Lunar politics through the lens of the one person from this period who will actually be important later. 2.6k words. Part of “A Sketch of History;” preceded by the Pre-Novan Lunar Period; followed by the High Human Tenure.

The 25th century saw the population rise from around five thousand at the birth of Evo Darwin to nearly three times that in 2499; as both result and cause, it saw the construction of six more domes in addition to the Prime and Red Domes we’re already familiar with. Prime Dome shifted to an almost entirely administrative function as the population moved out to the newer and larger Orange and Yellow Domes, erected early in the century; what wasn’t government infrastructure was First University, and the two were increasingly growing to be the same thing.

Anahita Moreau was born in 2442, three years after Mieke Nagtegaal published the Memoirs. She did pretty well in school, stayed away from boys, and eventually turned out to be both gay and, more scandalously, an electrician. She was also an ardent Red Hat, the first novan to join any salon—but we’ll get to that later. For her reformist activities, the Imperium, five hundred years down the line, would name her one of its pantheon of secular saints.

A few years after Anahita the Zamenhof line header was born, shortly followed by the first Linnaeus. In the remainder of the twenty-fifth century thirty-two more lines were created, and the term gento (roughly “clan”) started being attached to them. The focus of the novan project, which Evo Darwin joined as soon as she was able, shifted from “can we do this?” to “how do we make this sustainable?” thanks to major pushes from Evo, Espero, and eventually Anahita.

The novans’ position in society settled. They were legally considered human, the ultimate resolution of a series of nasty ethics questions that had emerged shortly after Anahita’s birth. The eldest three, as a matter of unspoken internal agreement, stayed as far out of the mess that was contemporary politics as they could, Adamo and Espero because siding incorrectly could doom their species and Evo because she was a reasonably normal person. They tried their best to keep Anahita out too, and until she was twenty they succeeded; but, again, we’ll get to that later.

Despite their seeming aloofness from contemporary politics, at this early stage every novan was expected to be a public figure, very open and with nothing to hide. They were almost exclusively referred to by their personal names, even at work and by the most formal of scientific publications. Everywhere Evo Darwin went, she was Evo, no matter if she had never met anyone there. The news called her Evo; strangers on the street or in the tunnels called her Evo. Her spouse actually started calling her Darwin for a bit because it felt more intimate. The first three tolerated it as an inevitability, but it disgusted Anahita Moreau.

But we’ll get to that when it comes around, because right now we have to worry about some history nerds. Early on, a group of human families raising first-generation novans (the first Linnaeus and a few later Darwins and Chikaondas) got together and decided they should raise their children speaking Classical Latin, because surely that was a good idea. The Academy, laughing, gave them official leave to do so, and even humored them by adding a Latin language course into the options for third-tier schooling.

Then it worked, and a fifth of the total novan population were now native speakers of Latin. Latin. By the end of the century it was as well-established as (the admittedly rapidly dwindling) English, and it had started spreading among the human population. Evo Darwin, sensing something important even if she didn’t know what, started learning it at once.

Terraforming proceeded; it was pretty dull stuff, except if one was directly involved in it. It looked to be a bit ahead of schedule, at least. Terranova, by this time often simply called the Planet, had a series of worrying earthquakes in the 2420s, but nothing ever came of that. Like I said—dull as dishwater.

More interesting was the political side of things, where the timescale for noticeable change was months instead of decades.

The Academy briefly released some of its political restrictions in the middle 25th century, after a Red Hat/Zeitgeist Movement liberal* coalition managed to get a majority, but that fell apart when the Zeitgeist political base, emboldened, staged wide protests to celebrate the end of the public-assembly laws just before the next election season. The body of the University—that is, mostly professors, students, and now politicians—had been the key electors of the Leadership Council, and they retained that role in the First Academy. They were none too pleased about the practical siege of their campus, and the liberals were voted out and replaced by a staunch restrictivist ticket.

* What “liberal” means in Shipboard and Lunar contexts is the opposite of “restrictivist”—liberal politics meant valuing social freedom enough that one would (at best) risk a slowdown in terraforming efforts and (at worst) risk catastrophe. Keep in mind that these people live in pressurized domes on a freezing, airless moon, with the only possible help either three weeks or twenty light-years away.

This went pretty poorly for everyone involved except the Captain’s Chamber, a reserved restrictive elitist* salon that took the majority of the seats and forcibly suppressed the protesters. There was little bloodshed; restrictivist Lunar politics had not yet come to allow such a waste of resources. Few outside the Zeitgeist milieu had actually supported the protests, but the May Crackdown—an overt, physical display of the authoritarian tendencies the Academy had developed in its legislative and especially executive functions—rattled them greatly. Such had never been done on the Moon before, and the stories from Earth were recalled with dread.

* See the commentary on the end of the Illustrians a bit further down for more, but in short: Favoring practicality/not visionary; favoring government control of society to improve productivity; favoring the interests of a meritocratic elite.

The ensuing Persecutions of the Zeitgeist lasted about a decade. They took the form of political purges in the judiciary and terraforming directorates, and the Movement (nominally not a salon, but everyone knew what it was) was outright banned. Known and voluble Zeitgists (a term for which I apologize, pleading that it’s what they called themselves) faced legal repercussions, and no Zeitgeist leader (of whom there were twenty, twelve of them very litigious) won a court case at any point in the fifteen years after 2455. The First Academy’s influence over the judiciary during this period was later cited as precedent for the Third Academy’s outright stranglehold in the years leading up to the Departure, and perhaps that is, although excessive, not a wholly incorrect comparison.

Bid adieu to the Illustrians; a rift over the Persecutions tore them apart in the late 2460s and they never recovered. Hastening their end was the fact that they had never actually been very large in the first place. They were visionary restrictive generalists, which essentially means that (a) they had grand(iose), often borderline utopian visions of what Terranova could be, leading them to approve of various idealistic causes their “reserved” counterparts disdained, and usually they were thrilled about—though often more invasive toward—novanity; (b) they believed that the government ought to exercise a strong and even somewhat repressive control over the population in order to accomplish the terraforming of the said new world; and (c) their program was generally focused on the whole population (open to them, trying to appeal to them, thinking the whole of righteous society should have a hand in legislation, that sort of thing) rather than exclusively the meritorious.

Restrictive generalists were never particularly common after the arrival fever died out.

Eventually tempers cooled and the most influential Little Captains (the term for attendants—that is to say, members—of the Captain’s Chamber) died or backed down; the Zeitgeist Movement, always a bit of a secret society, had now gained a justified persecution complex and lived on in the political underground; its always more public cousin the Red Hat Salon had been almost entirely stamped out. The Movement’s elitist counterpart, the Spider’s Nest, suffered some; but after their leaders publicly vowed their loyalty to the Academy as it stood as the best presently possible engine for the accomplishment of the terraforming and the preservation of the outpost of sapient life at Scientia (language carefully chosen to both pacify the persecutors and avoid alienating their attendants), they were mostly let alone.

Anahita Moreau came of age in that mess, and she sided—very vehemently—with the Red Hats. She got a lead on where they were meeting in the early days of the Persecutions and dropped by, startling the crap out of everyone. The novan silent policy was very well known, and for a while it was suspected that she was some kind of spy.

Then she hit a government official with a balloon full of ink and glitter and it became very clear she wasn’t.

This got her thrown in the slammer and badly rattled the other novans. The silent policy existed for a reason, and then there was sixteen-year-old Anahita, getting her mugshot in the paper for siding with the clear losers in a political death-match. Worse, she turned out to be a very effective public speaker, and very, very unapologetic about her philosophy. The possible implications, at least to the ever-vigilant first novans, were clear, and Espero in particular read Anahita the riot act about it.

The inking got Anahita ghosted by the Red Hats, but it gave her credibility with the more radicalized Zeitgeist. She started working with them to organize mostly-peaceful protests, and within the decade she had a sizable following of her own. The four Red Hats who followed her out became her seconds-in-command, and between them they led their splinter of the Zeitgeist to greater and greater influence.

By the time the Persecutions finally came to an end Anahita was thirty-two and had made a very good name for herself. No one official could pin anything on the Moon’s favorite electrician, and she had actually managed to exploit the automated meritocratic system to get back into University. She earned a master’s in philosophy, got disenfranchised after voting for none of the right candidates, and published—that is, put on the verified internet—a book summarizing her thoughts on morality and life.

Her followers and their movement were the Moon’s first true political party, not that anyone thought to call them one. No one really called them much of anything—they had no official name, to the point that they were just called “Anahita’s people,” or sometimes “the Anahita.” The Moreau by the same name quite enjoyed this, not least because to disambiguate her from them the press had to start calling her by her surname, like she was human (by which we here mean “not alive for the public titillation”). The day she turned forty she officially donated her given name to the movement, declaring that henceforth she would be known mononymously as Moreau. The conflation this led to between her movement and herself was, in addition to political commentary, probably the genesis point of her lasting presence in folklore.

* This, and the fact that her three children and two contemporaneous genetic twins followed her in it, creates a rather nasty task for biographers asked to disambiguate her from her kin.

The Anahita tended to share their membership with the visionary liberal salons, and by some later commentators they are summed up as an offshoot of the Zeitgeist. I shudder to think what avowed, though exiled, Red Hat Moreau would think of it if she knew. She was never known for an explosive temper, but few people actually want to receive a polemic in their inbox, no matter how politely it’s written. But, anyhow, “tended to” does not mean “always did.” Moreau kept the Anahita laser-focused on novan and wider sapient rights, so although they skewed very liberal and quite generalist they drew in affiliates from every salon except the Captain’s Chamber, whose attendants were not officially excluded by Moreau or the wider Anahita but were de facto barred out.

By the time the 26th century rolled around, the 18,478 residents of the Moon, the Anahita included, were totally and utterly done with political turmoil. There were a succession of moderate governments, and just as politics started getting boring things with the novans started getting interesting. There were now ten genetic lineages floating about, and thirty-seven current living novans. Evo Darwin, first of the novans, died in 2496. She was survived by her spouse, two sisters, three adopted children, and a bevy of nieces and nephews. She was not, however, survived by Adamo Chikaonda, second of the novans; he died two years before, survived by his wife, their seven children, and a nonviable population of his species. Espero died in 2500 flat, survived by seven children, a political movement she hated, and a nonviable, but growing, population of her species. They were all dissected after their deaths, an occurrence in which they had had no say, and then preserved as specimens after their funerals instead of being given the general dignified incineration.

After those rapid-fire deaths Moreau found herself, suddenly, the oldest novan alive. Under Evo’s watch the unofficial office of Firstborn had become the guiding light for the overarching course of novanity, and she had been seen as something like the secular equivalent of a spiritual mentor. She had helped young novans get into the University, advised them about how their bodies were likely to work, and even, once, advocated for one in court. Her house usually had at least one or two children visiting, and she was affectionately called grandma by most every novan (and a few of their human friends) born after she turned fifty. Moreau, although a relatively good mother and a gifted political leader, did not have that in her. She did adequately, but not well. This part, in case you can’t tell, tends to be left out of biographies.

(Incidentally, the Firstborn’s status evaporated shortly after she expired; as the novan population grew, the conditions that enabled the eldest of them to derive authority from age alone disappeared, as being the eldest stopped meaning one had significant seniority over everyone else. It was an artifact of the length of the gap between Evo’s creation and her successors’—not so short that she wasn’t any more mature than, say, Adamo, and not so long that she was an antique by the time there was enough of a population to set on her as a leader.)

I spend so much time on Moreau firstly because she’s interesting and secondly because of the immense impact she had on Lunar and novan culture. “Anahita” is the only early novan praenomen to never go out of fashion, not once; she commonly appears in folktales collected in the War Era and beyond as something between a folk hero and an outright saint; the Imperium, four and a half centuries down the line, named a government bureau after her. No other figure quite compares.

Of course, her fame is greatly helped by the fact that the total sapient population of the solar system, at the time of her death, was twenty-six thousand people, and at least a third of them had met her.

She died in 2534 at the age of ninety-two, which means her life solidly overlaps with the early Terranovan Settlement Period, covered in the next installment of this increasingly inaccurately named Sketch. Learning this tends to surprise later students, especially Imperial; the early Creation (initial five gentoj and the lifespans of their first line headers) and early Settlement Periods are generally treated as discrete historiographical units. Moreau’s dissection culminated in her ostensibly accidental decapitation by the coroner, and her body was the first and for a long time the only novan corpse to be incinerated. Her claws were, per her request, saved and distributed among her heirs.

Next: The High Human Tenure.

0 notes

Text

The High Human Tenure, 2520 to 2600

The Moon begins settling the Planet and the scope of our narrative expands dramatically. 3.7k words. Part of “A Sketch of History;” preceded by the Moon’s Favorite Electrician; followed by a dramatic rise in the population.

The beginning of the Terranovan Settlement Period in or around 2520 makes describing politics and events much harder, as evidenced by the fact that I’ve had to rewrite it three times and am getting increasingly annoyed with it all. Thus far we have pretty much dealt with the Moon and the Moon alone, as the nominally-inhabited Belt had only very sparse, very transient population and no political consciousness of its own; but the Settlement Period brings in the second of the Classical Three Worlds, and shortly after its end our third will form.

The Worlds, in case you’re saving the article for later, are a result of the information barriers inherent in living in a multi-planetary society. (Now, technically they’re a planetless society for a quarter of their history and for the rest of it they only have one that’s actually habitable, but nevermind that. The two or three population centers that exist at any given time have either an atmosphere or several weeks’ travel between them, and that’s good enough.)

The Moon is the first of the Classical Three Worlds, Terranova/o is the second of the Classical and first of the Modern, and the Belt—which is technically inhabited but either inert or entirely Lunar for the next and past few centuries—is the third of both.

Now, the Terranova of this period was by no means particularly habitable. It had absolutely bonkers weather, its atmosphere having recently been greatly altered; the oceans were shot through with bizarre bacterial mats; and, of course, there was always the problem of the seasons, which nobody who had grown up in the domes was quite prepared to really experience rather than monitor from a distance. But it was adequate for now, and the Academy was going to make people live on it.

In doing so, they have forced me to do something I’ve been dreading since I started writing this: properly introduce the Planet.

Terranova’s landmass, which I’ll have to discuss in another post because putting it here is such ridiculous burying that it’s practically criminal, is composed of one large supercontinent (roughly shaped like a very long two-headed leech) and two smaller continents that everyone who lives on the supercontinent after about 2600 calls the Islands. You can see an old version of this, from before I started getting into plate tectonics, in the icon and header image of this blog. Compared to that version, Lazar›’s shape is completely different and the Continent is much thinner throughout, but most of the relative locations are the same.

The Continent, which is thankfully thin enough that most of it isn’t uninhabitable desert and it—everyone hopes—isn’t particularly vulnerable to large igneous provinces and their mass extinction events, straddles the equator. Its body is mostly north of the equator, with one “head” pointing up into the Arctic Circle (this being the Headland or the Jabberwocky, depending on where you’re from) and the nameless other one crossing the equator back down into the south. These heads face the west; its tail arcs southward in the east, coming to brush almost against the Antarctic Circle.

Caught in the Continent’s arc is one of the Islands, later called Nowhere; it’s very roughly rectangular or trapezoidal and has a distinctive heart-shaped lake in the middle (very inventively called Heart Lake) courtesy of a ridiculous amount of luck. Its latter-day inhabitants are generally insufferably proud of their wonderful rocky beaches and their movie industry.

The other Island broke off from the outside of the tail and is now a third of the way along a collision course with one of the heads; it’s later called Lazar or Lazer’ or Lazar› (said /ˈlazər/ or /laˈzer/, neither of which sound like “laser”). We’ll get into why in a bit. Basically, a funny story and a hell of a lot of not-so-funny politics. (I would include a map, but it’s currently undergoing a redesign in which I properly consider how such a thing could have evolved.)

At this stage it had a wide array of lifeforms, most natural but a fair number engineered by bored scientists. They were generally thrown together in a chaotic hodgepodge, animals and plants from similar climates but dissimilar locations on Earth being dropped by robot anywhere it seemed they might fit and shake out into an ecosystem. Part of the settlers’ job would be to guide less erratic reintroductions, as controlled reentry would be much more easily accomplished with crewed flights than by simply shooting a ship and an automating program down and hoping for the best.

And, of course, there was the small fact that the end goal of all this terraforming wasn’t to pack up and go back to Earth. The whole Scientian population had been working for generations with only the promise that their children’s children would get to live on a habitable Planet, and “chasing the big dream” was one of the strongest unifying factors in Lunar (and by extension Belter) culture.

The Moon wasn’t an awful place to live, all things considered; but every so often there were meteor scares that left the population huddled in their houses, hugging their families, and hoping desperately that the defense systems were doing their job and whatever asteroid was threatening them all with boiling eyes and death by asphyxia had been shot off course or pulverized into still dangerous but not imminently fatal dust. That and the strict social regulations—even the liberals would be considered borderline authoritarian by Earth’s standards—left a large fraction of society jumping at the bit to get out.

Well, smash cut back to politics, where the liberals are no longer in power.

The excitement over the approaching Second Phase had, as most major terraforming-related events tended to do, pushed politics toward the visionaries and the restrictivists.

Citing the pressing and momentous nature of the current era, an alliance of visionary restrictivists in the Academy basically pulled an unacknowledged coup. This inaugurates the Second Academy, not officially differentiated at the time but marked by the adoption of the scientarchy model dreamed up by the said alliance and the Reforms of 2525 which put it into place.

A scientarchy is, first and foremost, a doggerel bit of Latin-Greek that originated in a political cartoon in Ilyasov’s time. It was adopted much later to refer to the system of government instituted by the Second Academy, initially by the regime’s critics (ironically, admirers of Ilyasov and his government) and then later as the official designation.

It means, or should mean, something like rule by knowledge or rule by the wise; what it meant in practice was an oligarchy of well-connected and pretentious academics with a worryingly efficient bureaucracy beneath them and strong state control of basically everything. The Legislative Academy, a twelve- to twenty-five-person committee (size depending on the number and severity of issues at hand), stood at the top and issued orders to those below. The electorate, “at this vital moment alone,” was narrowed to professors, terraforming scientists, and some graduate students.

The nascent Scientarchy was initially controlled by a coalition between the Blue Room and about half the Bricklayers, visionary and reserved restrictivists respectively; but the Blue Room had been its architects, and they were the only ones who survived the next election and the subsequent reorganization of the bureaucracy. Now, keep in mind that I don’t literally mean “survived;” I’m talking about their hold on power. Their political purges aren’t murderous, not yet.

The Captain’s Chamber, ironically, hated all this and broke badly with the Academy, getting most of its attendants fired in the process for “open” dissention. They found no friends in the underground circles, and eventually most of their membership exported itself down to the Planet.

While their leader was still alive the Anahita stayed just barely on the Academy’s good side, very carefully stretching the boundaries of what sorts of protests were allowed. Unfortunately, after the elections of 2505 the Academy shifted slowly, and then quickly, back to the restrictive. Moreau fought the Reforms of 2525 effectively till the end, but after her death the Anahita lost their most well-known public figure. Her four seconds-in-command did not long outlive her—the last of them fell in 2542 to an aneurysm, and with that the last best face of the Anahita was dead.

The Anahita, now headless, actually survived very well as a grassroots network; but they had lost the protection that having someone with Moreau’s prestige and prominence at their head had granted them. They made it their policy to stay just barely on the Academy’s good side, avoiding crackdowns while continuing to make their thoughts on certain acts and proposed legislation known. They became more quiet about their activities as a whole, which both gained them new members from the more reserved sides of politics and lost them a few disappointed older members, usually to the Zeitgeist.

The Academy, for their part, somewhat indifferently took Moreau’s death as an excuse to start issuing legislative restrictions on the Anahita, but since they were such an ill-defined body and it cared so little about them these had quite little effect. The Second Academy is not the Third Academy; it was only laying the groundwork. Some amount of political dissidence was still tolerated, and the Anahita, who took no official liberal or restrictivist position after Moreau’s death, were by far the preferable option compared to the radicalized Zeitgeist and bitter—and too clever by half—Red Hats.

That was the political situation within which the first Planetary Domes departed the Moon (or, more accurately, when their personnel departed the Moon and the domes themselves departed the Belt).

The Planeteers, as the settlers were for a very brief period of history known, would be physically isolated down there, and unlike the Belt there would be no revolving door between the Moon and Terranova to keep them culturally Lunar. Communication would be fast and two-way, yes, but it would be predominantly by radio and email—video would be used only for the most important of public addresses.

As a result, the early settlers tended to be visionary, and they tended to be loyal to the Academy. The former was a necessity of temperament—it takes a certain kind of person to volunteer for a one-way trip to the land of hard labor—and the latter was a necessity of politics. The Academy kept a stranglehold on the early process, feeling the atmospheric barrier between it and its Planetary subjects more acutely than it did the weeks’ travel between the Moon and the Belt. The latter set cycled in and out, remaining in effect a Lunar subculture; the former would, as said, be isolated: they would evolve in their own direction, and the Academy wanted as much control of that evolution as they could have.

Those who did go down were disproportionately novan. The early novan generations tended to take their cues from the Chikaonda/Darwins when it came to reproduction, though they looked to Evo for (coherent) ideology; consequently, there were a few hundred by this point, and many of the adults had gone into terraforming-related fields. They had no, or fewer, familial ties to the Moon, and for many of them Terranova represented an escape from the quotidian gratings of a life where the bulk of society still kind of marveled at them.

Beyond all that, the “people of the new world” bought even more into the propaganda than their human friends and neighbors. The sort of family that would choose to raise an early first-generation novan—and it was required to be a family in this period, not a single researcher—was usually rabidly visionary, though the rest of their politics could and did vary. Novanity was literally made for the New Planet (society having put their unsavory first few years behind them for everyone’s sanity’s sake), and some of them had come to see it as something between an ancestral home and the Promised Land.

The end result was that out of just under two thousand First-Wave Planeteers, 1,231 were novan. The Lunar novan population was almost halved.

The first domes, of which there were five spread across the Continent, had only numerical designations for their initial decades. They were initially very dependent on shipments down from the Moon, but by four years in one of the five was self-sustaining, and it was trying to coach the others into it. Anti-Academy sentiment simmered just below the surface, but never quite breached, as their populations grew.

Over time they developed little internal references to themselves, names more individualized than “Preliminary Dome No. 5;” those that planned it in an attempt to develop some sort of cultural identity usually chose something in the most common, or most favored, non-Esperanto language around. Unfortunately, everyone but the Belters was very out of practice at giving inventive names to things—the Academy officially frowned on it as “obfuscatory”—and the initial five domes broke no patterns.

One became Putiya Nakaram, “new city,” and another Bolŝaya Oblast’, “new province;” a third, Du Riveroj, was named for the most salient geographical feature around. Ìbàdàn, in the grassy plains of the later Metropolitan Northwest, was named for a city on Earth, and as a result had initial trouble getting its name past the Academy. Its founders were able to cite Du Riveroj as precedent, and the Academy eventually decided the Earth Ìbàdàn’s etymology—derived from Yorùbá for “by the meadow”—was just close enough to a direct description of the dome’s location to qualify as non-obfuscatory. Poor Pedro, on the other hand, was never able to get its name approved, no matter what it tried, and so it officially remained Preliminary Dome No. 3 until the Third Academy withdrew almost entirely from the Planet and it was able to do whatever it liked.

Terranova, helmed by these five cities, dramatically overshot initial population estimates. Harsh it was, yes, but quickly becoming more habitable; and, besides, wouldn’t you enjoy having natural, almost foolproof insulation from meteors and crashing spaceships? Better yet, there were no talent-based or able-status requirements to immigrate down, like there were for employment in the Belt, which wasn’t much of an escape anyway. One just had to be willing to do work and offer some useful ability or a set of hands, which almost anyone could.

More and more planetary domes were constructed, but, starting in 2549, they were quickly outrun by domeless towns. Unfortunately for historians, the first such town had no official name—no one realized they were doing anything more than setting up a pit stop along a trade route between two domes inside a mountain formation called the Vesica Montium. It was nicknamed Xiǎo Yú Zhèn, as a casualty of the dome it was nearest to; and this is how, a few centuries down the line, the second-biggest urban center in the whole of the Montian Territories came to be called “Little Fish Town.”

And now for something completely different. We’ve gotten to the inconveniently-timed bit where a Lunar Rusophone accidentally butchers his native language in an attempt to save it from the decay overtaking the heritage languages in the middle of the twenty-sixth century, and I have to explain what in God’s name all of that means.

Let’s step back a few decades and look at the language politics of the Lunar Period. Since well before Advent (though, it is generally held, sometime after the initial departure from Earth), Esperanto had been the common language; but in the early years it was rarely dominant. Children usually learned it only in school, and when an interlingual couple married they would learn each other’s languages.

But starting at around the middle of the twenty-fifth century, it started to seep more and more into being the only language children were seen as needing to learn, and all others were relegated to the status of “heritage languages.” More and more parents, especially from the major languages back on Earth, only passed on Esperanto. It was common knowledge that English would die out within two centuries, with French, Swahili, and maybe but probably not Mandarin following soon after; Russian and Yoruba, which had had smaller speaker bases to begin with, might take only one. All bets were off with regard to Latin, since although its speakers were few they—being mostly novan and thus having no ancestral ties, which left them desperate to make a culture of some kind—had grabbed it hard and held on tight.

Naturally, speakers of most of the dwindling languages were quite freaked out. Several launched revival efforts for whatever tongue they were a partisan of; few got beyond circles of about twenty people. Fewer still left major impacts, and the only one to merit a place in our history failed so badly that it wound up creating a new language almost unintelligible with the old one. That is the Butchery of Russian in the 2560s, spearheaded by the very-much-not-a-linguist Councilor Yulian T. Jackson.

For a more in-depth look at the butchering of Russian, please see Addendum II, which concerns itself entirely with it. For everyone else: Parrus’ is Russian’s bastard child with Esperanto, and let’s leave it at that.

The delightful freak of language that is Early Provincial Russian aside, the middle fifty years of the twenty-sixth century were fairly relaxed. The Terranovan population grew, and a new identity or fifty started to form; the Moon went through cycles of loosening and tightening restrictions, averaging out to a gradual increase in Academy control of menial functions; the population of the Belt, as ever, was exhaled and inhaled by the Moon.

Toward the close of the century things picked up, though not enough to meaningfully disrupt life anywhere. In 2565, one of the newer dome-cities in the Vesica Montium (a mountain formation in the northeast of the main continent) suffered a coup by a set of angry old Zeitgists and émigré lunar Anahita. They were re-overthrown by the original government in short order, but the Academy was furious beyond words. They issued massive reprisals against the poor dome, loosing a massive 5,000-man army upon them to bring them under martial law—or, rather, they tried to.

The Academy, although the unchallenged overlord of the whole solar system, couldn’t directly act on anything not under its immediate (read: Lunar) physical jurisdiction. On the Planet, to get anything done it had to work through a dome. If that dome ignored the order—well, firstly the Moon might never know, especially if it was over a minor trade infraction or tweak to the number of salmon in a local lake that didn’t merit checking in afterward, and assuming it did learn what had happened it would have to go to yet another dome, which might also just not comply.

This is what happened in 2565. The only army inside the Vesica, and thus the one the Academy tried to order out, was that of the Fisheye Dome, or more formally the Fish Bladder’s Glass Eye. (That sounds no less ridiculous in the original Chinese. It was named in a fit of whimsy* by its first settlers, and when no one actually wanted to use that mouthful on a daily basis it became simply Fisheye.)

* At the risk of getting too far in the weeds, the Fisheye is a Dreyer/Zamenhof Type II dome, entirely composed of clear hexagonal pseudo-glass windows except for the top, where a ring of solar panels almost like an iris stares up at the sky. The “Fish Bladder” bit is from a literal translation of the Latin vesica piscis, which gave the mountain formation its name.

Fisheye thought the Academy’s orders were horribly unreasonable, and most of their army was off protecting Xiǎo Yú Zhèn from the first of the land-pirates anyway, which made the proposal actually impossible. Instead, they set out a 500-man combination battalion and merchant caravan to blockade the offending dome-city and cut off all trade (save, of course, for that with Fisheye, which saw an opportunity to turn a tidy profit). To get away with it they sweet-talked their local Lunar ambassador (who, by a freakish coincidence, was Yulian Jackson’s second cousin Jonatano) into submitting a favorable report of their fidelity and high intelligence.

The Zamenhof/de la Cruz I #5 Incident, as it is snappily known, was an early portent of how Planetary administration would work from then on.

Sometime between 2580s and the 2640s—exactly when varies both by region and by analyst—Terranova settled into the Discipline Alliances, a diplomatic model in which every dome maintained good relations with and close ties to its neighbors, primarily to avoid Scientarchic retribution for smuggling, “gadabouting,” disloyal communication, and other common vices of Planetary life. To the Moon they explained these ties as enabling them to conduct better discipline rather than avoid it entirely, not that anyone except Princeps Professor Mercator (we’ll get to rin) particularly believed that; and furious as the Academy was, once an Alliance was in place they lost real control over the region and there was nothing they could do about it. Usually.

Fisheye and the now-stabilized dome, finally having been named Ĝenevivo, would enter into one of the first Discipline Alliances in 2572. The whole Vesica Montium region would enter into some of the tightest, and when a mutant strain of Catholicism started to spread in the region it would find easy passage along their robust trade routes.

(As for that mutant strain of Catholicism: I clean forgot the First Terranovan Schism, Catholic edition, happened when I was writing the section on pre-novan history. I shall instead cover it in an addendum and redirect you there as soon as possible. It’ll definitely come out before the history of the War Era, and please treat it as something like part 3.5. The W.E. is the first period wherein religion becomes important enough to enter strongly into the telling, and the Catholics in particular see their major governmental influence last longer any other theocracy.)

Next: The Population Explodes.

0 notes

Text

The Population Explodes, 2600 to 2680

Borne on a geyser of new births, the Academy rises to new heights of authoritarianism at home and falls to new lows of influence abroad. 3.5k words. Part of “A Sketch of History;” preceded by the High Human Tenure; followed by the Third Academy.

In the 27th century the population hit the point where one started really being able to tell it followed exponential growth. The population shot up from around eighty thousand at the turn of the century to more than three hundred and sixty thousand, largely on the Planet but sending domes mushrooming up (and down) all across the Moon as well. The novan population, pegged at 8255 in the census of 2600, was more than ten times that by 2699.

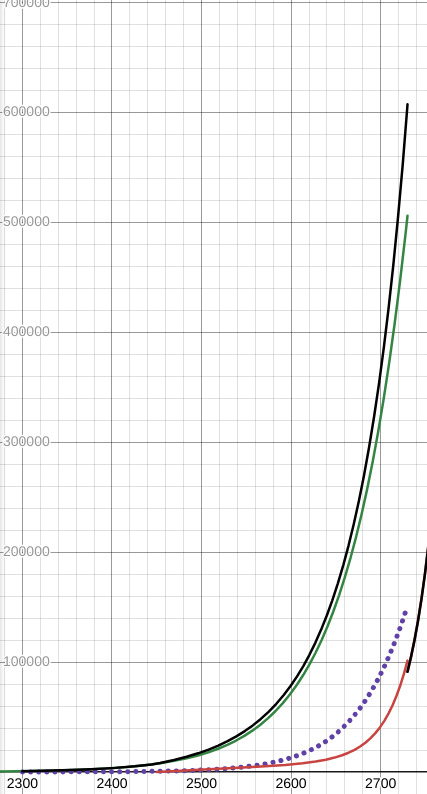

But still, this was a society that had been well below a hundred thousand for three centuries. They didn’t know, really, how to deal with this many people, hence the ballooning, structureless cities around the domes. I’ve roughly modeled the increase in Desmos, and I think seeing it may help drive the point home:

Black is total population. Green is human. Red is novan. Purple is the fraction of the total population that is novan, times a million to make it scale nicely with the rest of the graph. As for what that drop is, and why the green line just stops—don’t worry about it :)

I’ve been mentioning the population numbers intermittently to try to give you some sense of the scale of all this, but I want to explicitly call out here how tiny this is compared to what we’re used to on Earth. The population of modern Boston alone is more than one and a half times the total population in 2700, and despite its rapid growth the 2600s novan population could have all been enrolled in a single University of California. A dome-“city” usually started with a population of 400 to 1,000, and the largest reached only about 30,000.

Be really glad the guys on Terranova have trains, or else we’d be talking about an area about the size of the Oblast’.

Most of the new people were on Terranova, where breeding rates were something like the Wild West and a given family could be expected to have somewhere between two and seven children. This was officially encouraged by the Academy and the governments out of many domes; the latter often offered incentives. The Moon kept its numbers more in check thanks to the exigencies of dome life, and before the midpoint of the century and the rise of the Third Academy the Belt can mostly be considered part of them. Nevertheless, “more in check” does not by any stretch of the imagination mean “stable;” lunar dome construction greatly accelerated, incidentally contributing to the growth of what would become the Belter population.

So that’s going on in the background of the political developments we’re going to talk about next, and although I shall stop harping on about it presently, please keep in mind the psychological pressure the increase puts on our players going forward.

Through the first half of the century, Terranova saw the solidification of the Discipline Alliances, because if you can be something between anarchist not-quite-pirates and a bunch of semi-autonomous colonies completely without political repercussions from On High, you’re usually going to try.

The Scientarchy model, inherited from the Moon, dominated government. On the Planet it took the form of a relatively small committee elected by the classes formally involved in higher education (and, if there were a particularly large quantity of generalists, sometimes enfranchising anyone who had ever earned the equivalent of a bachelor’s) serving as the executive and the highest court of the judicial branch. The scientarchies will earn their own post one day, probably accompanied by an examination of their evolution over time from the Lunar model through the intermediaries of this period to the Putiya Nakaram Scientarchy of the War Era and early Imperium; but for now we don’t have to care about that, and I’m largely leaving this as a reminder to my later self.

The characters of the governments and their people, although uniformly more liberal than the Moon, differed by region, or more accurately by climate and geography. Harsher territory tended to produce more centralized, autocratic regimes. They tended to have trouble sustaining their population numbers, and to avoid falling into decline they often depended on new immigrants from the Moon. On the flip side, a lush, forgiving climate where one could go out and live off the land for a few weeks if one had to tended to produce hyper-liberal not-quite-states, with something of the attitude of college students of our day cutting loose after growing up in deeply restrictive homes. In their intoxicated infatuation with freedom they made a variety of incidental and not-so-incidental decisions they would come to regret later, once their world became one in which international and interplanetary politics could seriously screw them over if left unattended.

But anyhow, these extremes, like land-pirates, were relatively rare—everyone heard about them, but most domes fell in the middle, and although domeless cities skewed liberal they did too. As for the other political axes: the planetary enterprise had been dominated from the get-go by visionaries, so no surprise there when I tell you that such sentiments were by the early 2600s almost universal on Terranova; the third axis varied wildly between ivory-tower elitism and radical generalism, with elitism tending to be more common in dome-cities and generalism in the domeless settlements growing up outside such favor.

In the increasingly common middle situation, where a sky-bared or “weathered” city had grown up outside an old dome, there was usually a stark class divide between those who dwelled under not-quite-glass and those who would suffer the rains on if a storm passed over. Education was universal and rigorous and penetrating the glass wall was actually quite common, at least in the first half of the century, but the divide remained.

It is during this period that the domes came to be called nuclear cities, either after the notion that they were the nuclei of their provinces or because, from above, a dome in the midst of its peripheral weather-city resembled a cell with a prominent nucleus. (Many, but not all, did have nuclear reactors in this period, so that is a persistent folk etymology.)

Speaking of, over the course of the century dome construction dwindled and eventually died off. From the Academy’s perspective, the Planet now had sufficient stable population to be able to settle things on its own, and people were used to the idea of seasons, so the supply costs of erecting a dome were now far higher than the benefits. The erstwhile construction materials, as a happy bonus, could now be routed to the Moon to put up housing for its own expanding population.

The dwellers on the said Planet were variously happy and unhappy about this. On the one hand, a dome life was more stable; on the other, it rasped the pride of many more independently-minded Terranovans that such relics of the Lunar way of life were even now the seats of higher government and of the developing culture.

To the novans this was especially galling, as humanity maintained a tacit and almost accidental dominance in the uppermost halls of power. Novans had made up almost fifty percent of the Planeteers, and because they had all known each other for years (and the settlers were very idealistic, and the harsh conditions of the Planet forbade the inefficiency of species division—and, and, and; I’ll leave the speculation to the historians) novans and humans were basically interchangeable, and at that early stage government, along with every other office, was pretty evenly split.

But ever since the second wave had come, humans had flowed almost resistlessly into the high halls of power. As more immigrants sluiced down from the heavily human general population, the Terranovan species ratio came closer to that of the Moon, and the “lint-trap ceiling” came with it. It had been standard on the Moon for every figure of authority above a certain level to be a human since quite literally forever, and for those latter-day novans who remembered or rediscovered the equality of the Planeteers the current state of Terranova was, to put it lightly, very disappointing.

Add this ancient grievance to the novan exceptionalism beginning to be bandied about in some circles—at least, more openly than it had been on the Moon—citing novanity’s role as the new species for the new planet, to the exuberantly liberal political atmosphere that prevailed almost everywhere on Terranova, and to the Scientarchic governmental structure described above, and you get the circumstances that made the Planetary Anahita so different from their Lunar cousins.

The Planetary Anahita were radicalized; that’s the best way to put it. In liberalism they far surpassed the Zeitgeist, being matched only by a few sub-sects of the Bricklayers, whose planetary division had recently splintered. They were almost entirely young and perhaps sixty percent novan, and where the Lunar Anahita were usually a more measured and reasonable opposition than the Academy deserved, the Planetary Anahita were often outright revolutionaries. This would have galled Moreau quite badly; she really was a Red Hat in temperament, a little more reserved than many of her followers, and her political conditions were, if they were anything, far more deserving of a revolution than the comparative anarchy the Planetary Anahita were given to play in.

It is a testament to the liberty accorded to those on Terranova that there were no mass arrests of Anahitists, especially after the political inkings and strikes—especially strikes, which went against both wider Scientian social norms and the specific purpose of the Planet—started. (Due to the very small population, murder and especially mass murder in acts of terrorism were unthinkable. Some vestiges of this mindset will continue through most of the War Era, rather discordantly chiming against the horrors of their surroundings and probably preventing novanity from outright annihilating itself.)

Of course, the reactionaries had their day as well. Plenty of days, really, as they had the Second Academy’s full-throated support in their nonviolent activities and tacit support in their more military enterprises. The reactionary regimes were the Academy’s eyes and hands on the Planet, and without a hand there is no way to wield the rod, so it encouraged them to form wherever it could. That is why we must now introduce our next historical figure.

Princeps President Mercator seized power in a coup. Born in a little farming town in the Jabberwocky (a geographic feature later known, in part, as the Headland), it did not take long for Fabius Mercator’s intelligence to become clear, and at ten re received a meritocratic and mandatory admission to a high-performing school inside Dome Helena. Helena was the local administrative capital, and young Mercator, who was separated from ria parents in the move, grew up in the privileged upper strata of Jabberwockish society. Re wined, dined, and hobnobbed with the best of them, and when re graduated it was remarked on as a darn shame that that talented young novan would so soon be leaving them. Most merit students with Mercator’s sort of background went into provincial administration, so much so that if one did not look closely one tended to assume there was a rule to that regard; Mercator, however, liked ria cushy city lifestyle and made rinself an exception.

Through a combination of connections and genuine aptitude, re embedded rinself in the Department of Civilizational Management, rising quickly through the ranks. By ria forty-fifth birthday re was its Regional Vice Director, an appointed post not vulnerable to change-over in what anemic elections Helena held. This, combined with ria natural aptitude for networking, put rin in a position where re heard everything, and re began to fancy rinself a kingmaker. Re was a reserved restrictive elitist by temperament, like most of ria Department, and when in the elections of 2632 the students and faculty of Helena University elected yet another slate of mostly liberal generalists to the local Scientarchy, and the Lunar-appointed governor seemed inclined to go along with this nonsense, re was incensed.

By 2634 re had come to a simmer, and it is believed to be in this year, when the Anahita won an initial toehold in the Helenan Academy, that its Lunar counterpart made contact with him. It was all indirect, of course, but Mercator was given to understand that if re were to “do something about” the situation, re would have the immediate allyship of the Moon and its resources. Re thought about it, and, although re perhaps never intended to act on them, re started laying down plans.

Three years later, the Anahita and the Zeitgeist won a plurality of seats on a platform of widening suffrage to everyone with a bachelor’s degree and an investment in terraforming. Mercator lost ria temper quite badly, and three days later re and a cadre of fellow magisters evicted the Academy from the city and declared themselves the legitimate government.

If you haven’t guessed from the surname, Mercator was a novan from a recent line—ria father was the firstborn of the second generation of the Mercatores—and ria coup made rin the first novan mayor of a dome-city. The Planetary Anahita were rather bitter about this, as they had wanted one of their own revolutionaries to end up wearing the earpiece and bullet plate.

Re was then dictator of Helena Dome and environs for the next eighteen years, in which time re was the Academy’s most loyal (and most lavishly treated) means of action in northwest Terranova, although re was known to bite the hand that fed rin if re thought the food were poor. Re had the force to—ria coup had inspired copycats, who, when they didn’t form independent fiefdoms safe in the arms of the local Discipline Alliance, answered more to rin as the interpreter of the Moon’s will than the Moon itself.

This is not to say that re wasn’t an upstanding member of the Disciplinary Alliance of Little Europe and the Bay whenever it came time for the Academy to bring rin back to heel, of course. In Mercator’s priorities, “dictator” came first and “Lunar loyalist” came maybe fifth.

It is also not to say that the Moon was the unambiguously dominant partner in the relationship; on the contrary, on the several trips the Princeps President made up there, re found rinself in a position to issue orders to just about anyone short of the Academy themselves. Re generally had the most guns on or in service to ria person of anyone a given Lunar had ever met, and re was physically imposing, standing six foot eight, the which two facts could not have hurt; but more importantly, re was just about the only true ally they had on the Planet toward the end.

In short, re was the sort of duke kings are scared of.

Re will be with us for a while, so now let us turn our focus to the Moon for the accession to power of the Spider Triumvirate, alternately called the Red-Brick Ruffians, in 2652. Their names don’t matter for this fast recounting—and an addendum will be going up shortly with a more in-depth look at them—and they had been exiled from every salon, but they aligned politically with the Princeps President and ria goals, and it was largely by ria influence (re being on the Moon for other reasons around election time and making veiled threats to the right people) that they were “elected” to the Primary Board of the Academy and quickly secured full power for themselves as an emergency executive committee.

The Spider Triumvirate saw the skyrocketing Lunar population and the almost total loss of control over the Planet and concluded that the only thing to be done was to withdraw inward. Over their three decades in power, they almost entirely handed Planetary affairs over to a network of loyal agents there, maintaining only a cultural role as first among equals for the Moon.

To decrease their dependence on the Planet they encouraged the development of permanent mining operations in the Belt, incidentally giving that world its first stable population. To this end they revived the old notion of the corporation and created opportunities for vesselbuilders* and -owners to make a tidy profit designing and operating large, rapidly-spinning, barrel-shaped spacecraft, taking advantage of the same mechanics as the Grand Voyager that had brought everyone to Scientia in the first place.

* “Vessel,” which became popular after a dispute about what should be termed a “spaceship” versus a “spacecraft” versus a “voyager” for legal purposes collapsed in on itself shortly before Settlement, is the generic name for a spacegoing vessel, as “ship” is for their seagoing counterparts.

On the Moon they centralized power in themselves, suspended the elections, created a department of censorship (unprecedented in Scientia, at least officially, and utterly scandalous), and brought the judiciary completely under Academy control. This met with resistance, which was met with crackdowns which exiled many of the arrested to Princeps President Mercator’s territories on the Planet. (The Princeps President, not being an idiot, then shunted them off elsewhere, preferably as far away as possible. For the most part, this ended up being Second Crossroads, in the middle of the southeastern plains and semi-desert, and inadvertently changed the city’s demographics so much that it made itself into a spaceport rather than simply a waystation on two land-based shipping routes.)

The Moon was about evenly divided on whether the Triumvirate were a good thing or a bad, but the vast majority of Terranovans believed the Red-Brick Ruffians (the which name a Terranovan pundit coined, after misunderstanding the complicated Lunar salon system) were abhorrent, unscientific dictators. The remaining twenty-five percent thought that whyever the Moon had taken its hands off them, the change was good and they should keep it up. That was the Discipline Alliances’ raison d’être, after all—keeping the Moon out of Terranova’s business.

Princeps President Mercator was finally assassinated by revolutionary Anahita in 2655, after eighteen years a-reigning. Re was the first true Terranovan dictator, and re would be the last until the War Era. After ria death, the territory re had controlled—the protrusion into the bay between the Headland and the body of the Continent, and large parts of the below-Headland northwest—collapsed into anarchy. The protrusion, called Little Europe for its shape, settled into a constellation of tiny city-states, each just weaponized enough to deter its neighbors from conquering it; the portion of the northwest that was south of the Headland held together under a succession of renewed scientarchies (imposed by its southern neighbors) until the outbreak of the War Era just under a century later, at which point it splintered into the kaleidoscope of small countries collectively called the Metropolitan Northwest.

With Mercator dead and the Discipline Alliances in full swing, the Academy had lost just about the last of its influence over Terranova; but the Moon as a concept had not. As I said above, the Moon was a first among equals culturally; it was far and away the oldest civilization, the fountainhead from which everything else derived, and as such it maintained a hold on the collective psyches of both the Planet and the nascent Belt. Cultural developments on the Moon—music, literature, accents, some public figures, basically everything short of official politics—tended to be copied on Terranova, as clearly the most advanced, most scientific way of doing things.

Less important, but something which should give you an idea of how the Moon was seen, is the fact that it was still the seat of most of the ancient religions—such that had seats, anyway, as many were either originally decentralized or had become so because of the extremely defanged varieties of religion that tended to make it to Scientia. (There is an addendum on this forthcoming.) Of those which did vest control of themselves in one body, Catholicism in particular both kept its pope on the Moon and hauled its Terranovan cardinals up, at great expense, for papal conclaves. Sunni Islam, though not reliant on one leading figure in the same way, tended to subconsciously give primacy to Lunar muftis over Terranovans, and that pattern repeated itself for Protestant Christianity and most other types of religious jurisprudence.

I have no transition for this, and for that I apologize, but we must bid a slow adieu to the Triumvirate. Their reign was thirty stable years long, and as can be expected from that, they went out not with a bang nor with a whimper, but with a handpicked table of successors to continue their work and their rule, while they themselves sat back, cooled their heels, and watched the sunset from top-level Prime Dome apartments. They had inaugurated, and would be succeeded by, one of those few political systems which leave behind quite literally eternal ramifications.

And now, absolutely bloody finally: the Third Academy.

Next: ...guess.

0 notes

Text

The Third Academy, 2680 to 2731

Come on, bring that lighter a little closer to this powder keg... 3.5k words. Part of “A Sketch of History;” preceded by a dramatic rise in the population; followed by the War Era.

The Third Academy was the government that took humanity out of the Scientia system, and that is all later commentators remember them for. They were formed of the generation of politicians—career politicians now, not even pretending to be scientists despite claiming learned titles—which came of age under the Triumvirate and studied at its knee, and most of their policies were natural progressions of its, just slightly refocused into human-centrism.

Unlike the Triumvirate, which was a single regime, the Third Academy was a system of governance that lasted multiple generations. In external appearance it was somewhat like the late Second Academy, being a bicameral (a lower chamber of forty members and an executive committee of a variable but much smaller number) authoritarian regime drowning in paperwork. The members of the lower chamber were even elected, though of course the popular voice could not be trusted with so important a matter as actual rule, and the executive committee selected its own replacement members from within the lower chamber.

The executive committee had complete control of the police, the judiciary, and the University, finally rendering the latter an organ of the state rather than the state an organ of it. They had military force to back their political censorships and blacklistings, and after the first decade they barely bothered even citing precedent.

They were entirely human, and that, initially unintentionally, made novanity an underclass. It was an extension of the Third-Academy-standard isolationism—in the rapidly-expanding population they saw a situation in which, eventually, resources would have to be starkly prioritized, and as in-groups have done for millennia they saw the out-group as ultimately more expendable than they were. Until that time came, the early Third Academy resolved, they would be even-handed; but, that said, they notably favored members of their own species in everything from legal disputes to authors taught in tertiary-school courses.

Thanks to hundreds of years of prizing intelligence above all else, and the fact that most of even the human population thought the Third Academy were an idiotic bunch of assholes, Lunar culture did not come to expel novans from most of their social roles. They still became professors and scientists at the usual elevated rate (thanks ultimately to an anxiety about their role as a people without a history trying to make themselves worthwhile, or in other words to some of the same thinking that led the Third Academy to consider them potentially expendable). But as the government became a de jure in addition to de facto human old boys’ club, they found it more and more impossible to come into any sort of power. In the religious hierarchies, they retained about the same representation they had before: deacons and bishops, but no popes or metropolitans, let alone patriarchs.* The most influential imams and muftis were always human; most other religions with any sort of leadership role followed that pattern as well.

* The organization of the Orthodox Church of Terra Nova deserves its own post, as it diverges in a few ways from any of the Orthodox Churches on Earth. So does Terranovan Catholicism, as, for obvious reasons, it fragmented around the time the Scientian cardinals elected a pope. (Er, elected him to be pope in effect; their actual justification is complicated in the extreme, but basically, Jesus is the invisible head of the church, the Bishop of Rome is the visible head, and the Terranovan pope—the bishopric varies—is the acting head.)

Like most elite regimes without a base of popular support, the Third Academy enforced its will by sheer might. Under the Second Academy the opposition found their lives difficult; under the Triumvirate they found themselves exiled; under the Third Academy they might just find themselves shot.

The first such execution was that of Amparo Sommer, the twenty-something eldest child of a (human) low-level Academy-aligned politician, who had turned against ria parents’ ideology and used ria University access to rail against it on the internet. Ria ideas had developed something of a following, and in killing rin the regime accidentally created a martyr. The news even reverberated down to Terranova—what do you mean, the Lunar bastards are killing each other? A similar scandal had happened in Nowhere, one of the Island continents, a decade before, so they were more familiar with the concept of a political execution than the people of the Moon, but after so long so zealously protecting life lest civilization itself be wiped out, it was still borderline unthinkable.

Then the Academy just kept doing it, over and over, for decades, and it slowly faded out of the headlines.

Unlike most authoritarian regimes on Earth or Terranova, no armed resistance to speak of arose. All a prospective Lunar rebel had to do was look up from ground level to remember just why they were so dependent on the tyrants. In any open conflict—not just against the Academy, but anywhere on the Moon save for the lowermost tunnels—there was the horrible risk that something vital would break, the most vivid example being the not-quite-glass of the domes themselves. They were in point of fact extremely difficult to scratch or crack, let alone shatter outright, but since the Second Academy they had neglected to broadcast that fact to the wider public; the logic was that it would then seem as if the Academy’s strong defense was protecting the fragile and life-giving dome glass from the dangers of the void outside.

That logic proved correct, and it worked wonders both at preventing armed revolt against the Third Academy and, later, at bringing about the first Scientian democracy.

For now, most discontented Lunar types voluntarily exiled themselves to the Planet, never to return. The lower rungs of the Academy were happy to help them, still reeling from the concept of political executions and looking to prevent whatever they could.

In this way the Academy created a fairly stable regime, and it lasted fifty years. Historians usually divide it along the several coups d’état, but in point of fact the interchanging of individual political actors did little to alter the course the Moon was on, apart from directing the spoils to this or that human family. For our initial summary purposes, we can treat everything except for the last decade or so of the regime as one cohesive authoritarian quagmire.

We also have to do this because our records of the period are extremely spotty, comparatively speaking. It is estimated that only ten percent of government records from the Third Academy survived the Departure; of that, ten percent was lost during the Anarchic Domes period; perhaps sixty percent of the remainder made it down to the Planet before the Devastation, bringing the total record survival to about five percent of the original.

Don’t get me wrong: they produced an immense amount of records, far more in a decade than in the also-targeted Shipboard and Early Lunar periods combined, so we have a pretty good understanding of what happened and when; we just often can’t dial past the initial fuzzy resolution to the granular detail.

So those were, as best as we can tell, the circumstances on the Moon ten years before the Departure. Things on Terranova remained about as described previously, apart from the states of various petty internal wars; the Lower Jabberwocky Scientarchy was in the process of pulling apart, and the Disciplinary Alliance of the Vesica Montium was in the process of knitting together into a single unified state.