Text

Not dead yet!: Marking my 2-year anniversaries

On Sunday I marked my two-year “cancerversary” of my diagnosis and on Tuesday a member of the support group I co-founded (for young women who are stage 4) died. Like me, she had triple-negative breast cancer. Like me, she was diagnosed stage 4 two years ago. Like me, she had exhausted several types of treatment (because triple-negative is a beast) and was looking for the one that would work. She asked me about Saci (Sassy!) and proposed trying it to her doctor less than a week before she died. Nine days before she passed she joined our Sunday cancer yoga group from bed at the hospital to join our meditation exercises. Like me, she remained confident and positive and absolutely refused to give up hope. (Like me, she also wore her hair purple sometimes.)

There were many things that are unlike about us too. She had two teenage children who now don’t have their mother. She was twelve years older than me and had had Hodgkin’s before she had breast cancer--even worse luck than mine, to triumph over one cancer only to get this diagnosis. Unlike me, she wasn’t strong enough for Saci, the only targeted triple-negative line of treatment, because her body had reacted badly to immunotherapy. She was in the hospital for two weeks with somewhat mysterious symptoms all of which added up to her body shutting down. On Saturday she went home with her family in hospice care. 2 days later she was gone.

It’s not usual for things to go so fast. Typically, doctors, patients, and family members all have some advance warning and patients spend a solid amount of time in hospice care. I am sure that people will ask me why it went that way for her. I’m asking myself why too, since it is so shocking and so entirely unfair. The fact that it can happen that way at all is frightening to me as a fellow patient since it’s the scenario of nightmares. That really could someday be me. No one ever wants to think that--and I cannot live my life focused on it either--but it has to be acknowledged as a possibility.

[More below the cut about memories from 2 years ago today and hopes for the future. Also, an invitation to contribute to some writing if you want.]

Today, January 28th, is the 2-year anniversary of my stage 4 diagnosis. In a way, it feels more significant than my initial cancer news. I had four days being horrified, but thinking that I would get through this as a phase in my life. It would be terrible--I’d have a double mastectomy, scorched-earth chemo, radiation, anything to get rid of the cancer--but then it would be done. On the Monday following my first set of CT scans I learned that that was not true. My lungs were full of tumors. (Later, after lots of waiting, MRIs and biopsies, I'd find that my lymph nodes, spine, and liver were affected too. I still have tumors in all those locations, but no new ones.) I wrote a description of getting that news in an email to a friend over the summer, after I had read Anne Boyer’s "The Undying”:

“The worst part about the lung tumors for me was that my dad had gotten a very early flight and I learned the news while he was in the air. My mom told me we could not text or tell him on the phone, that he would need to be with us both. So I drove to Newark straight from the doctor's office. It was in the teens outside and windy as we slogged to the baggage area where we were to meet. I saw my dad in his warmest and ugliest puffy orange down jacket, looking small in it, forlorn and horribly vulnerable. I fell into his arms, thinking at least that airports were such horrible places, so impersonal and banal, that no one would look twice. 'It's in my lungs,' I said into his shoulder so that I would not have to see his face. I was crying into the jacket that somehow smelled of winter cold even though he had been inside for hours. 'Please, Daddy. Fix it, please.' I spoke like a child because, on some very deep level, I think I really did still believe that my father could fix anything. I was embarrassed, though, and so I tried to stem my tears as he put his big hand on the back of my head and said, 'Oh sweetie, we'll get through this. We will.' I knew that really he could do nothing--and that this was his nightmare of powerlessness--and so I sniffed and blinked and I did not let myself cry again until June.”

Two years later this moment seems as if it just happened. The impact of my diagnosis on everyone dear to me, and especially my parents, is one of the worst things about it for me. We all know that there’s only so much “better” I can get, with the current science, and we’re all playing for time while the research moves forward towards something better, something that would make this a treatable chronic condition. I go back and forth, emotionally, on how likely I think that is and how good my position is for the future. Right now, comparing myself to the group member who died, I feel relatively fortunate, even as chemo exhausts me, I lose every scrap of hair that was ever on my body, and I spend half of my days being almost unable to eat from nausea and loss of taste. I feel glad that I was able to get Saci, that my body has so far stood up to the ceaseless trials I have put it through, with four treatments and surgery (and full-time work and living alone etc. etc.). I feel strong, not scared, even as I feel the emotional toll of terrible loneliness from covid isolation, winter, and carrying a sick body through my days alone.

I do not love the “fight” metaphor because so much of having an illness is completely out of your control and I never want to take myself (or anyone else) to task for “losing.” And so instead I will praise my body for enduring. I will praise myself for my enduring also, in both an emotional and physical way. I checked back in on how I was feeling as this anniversary approached last year and was pleased to see how much better I feel about it now, partly as a function of being in a treatment that is (likely) keeping me stable rather than in the midst of choosing another new one. Here is what I wrote back to my group of friends in November 2019, the run up to the one-year mark:

“I’m feeling like I can’t plan and don’t want to celebrate, like I can’t perform “fine” for the people in my life to spare them from the pain I’m causing by not doing better and feeling horrible about it. Perhaps it would help if I let them know that they didn’t need to perform “fine” for me? I understand the desire to protect me from the obligation to take care of them and appreciate it. But sometimes it can feel like I’m the only one experiencing anger or grief or pain, though I know I’m not. Feeling so isolated in my emotional response provides no catharsis for it. Compassion and sympathy function on the notion of “fellow feeling.” If you’re just out here, feeling by yourself, you can’t expect any comfort. As always, I think of the moment in the Iliad when Priam and Achilles cry together over dead Hector. Grief (and you can grieve for many things aside from a death) is something explicitly to be shared.”

So I guess I’ve shared it here. I can do that. And I can do another thing, which is to tell you I love you. People don’t really say it enough and reserve it too entirely for romantic contexts. It’s weird--it’s not like we are wartime rationing love! And every time anyone says it to me it helps. It’s an affirmation that I am integral in some way to people’s lives which, in a society that so greatly valorizes marriage/partnership and children, is something I can be in doubt about.”

There are some things I like here, though, and that I would now like to reiterate and invite you, my far-flung friends, to do for my 2-year milestone. Never has the notion of “fellow feeling” in times of grief and depression hit harder or been more important than during covid. In a way, the nation (or even world) was forced into much the same position, emotionally and practically, that my cancer put me in. People are isolated, unable to perform “fine” and wondering if other people feel the same way, or even if any of us can take care of each other at all. I am here to tell you that you can. Maybe not immediately but--sooner than you think--you can. Emotional reserves may be low but reaching out to support someone else can actually replenish them. You do not have to feel alone, or to feel, alone.

And for me, for this milestone and for the cancer-related depression that I certainly do have, I’d like to invite you to help me, so that I can do the same for you. I invite you to write something about how this milestone feels for you (either about me or not), how it relates to all the other insane things going on in the world or with you (not about me at all), how you felt on the original day when I shared my stage 4 diagnosis (definitely about me)--really anything that is on your mind or in your heart.

“Oh great,” you may think, “the English PhD has asked us to do homework!”. But no! It's up to you what you do. Write in whatever form you want, however long, even anonymously. And if you do I will write you back! Not with grades or comments, but with something to connect to what you shared. It is a way to create fellow-feeling; to open up, connect, heal. With me, yes, but also as the group of extraordinary people who have gone with me so far on this hard road. It’s a very different proposition to support someone through time-limited treatment with a good outcome than it is to sign on for whatever comes next. You are all, truly, pretty extraordinary.

Anyone who wants to send a note or reflection can email me or drop a file or post in this Google drive folder. Like I said, feel free to share whatever and do it anonymously if you’d rather. You can also askbox me here (better than DMS) or submit a post to this blog. (I'm taking a chance with open DMs for now...we'll see if that needs to change.)

I am grateful for all of you every day, but especially today.

Love,

Bex

p.s. The title of this post refers to the cinematic classic "Monty Python and the Holy Grail," a film my high school self and friends loved. They, along with other wonderful folks. gave me a "cancerversary" cake with "Not dead yet, motherfucker!" on it this Sunday.

p.p.s. The average life expectancy for people who get this diagnosis is 18 months to 3 years. Hitting 5 years would be extraordinary. Starting Year 3 is a huge deal and I have every intention of being extraordinary. (Never been average at anything in my life...I either succeed spectacularly or fail epically!)

#my life as a cancer patient#cancerversary#stage 4#mbc#metastatic breast cancer#personal#memories#bex writes#writing invitation#quarantine life

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brighter from Here: 'Tis the year's midnight, and it is the day's

Hello friends,

Happy Solstice! When they were younger--before I was born--my parents used to throw a solstice party. They served things that were spiny or hard on the outside and soft within (pineapple, coconut - Mom makes a delicious ambrosia) and celebrated the passing of the shortest day and longest night in the company of friends. I'd like to mark it here with you. I had hoped to have time, space, or energy to write a post that reflected more on the idea of the long night and of the distance still to travel from the dark. Maybe later. For now, I have two things to share with you.

The first is a piece of good news: my most recent scans were good enough that I am able to stay on this treatment! They weren't a miracle cure--it's more stability than anything else--but since that is better news than I have had since June I will take it. And it is a relief to know that I did not lose all my hair only to change immediately.

The second follows at the end here. It's one of my favorite poems, John Donne's "A Nocturnal Upon St. Lucy's Day." I'd like to write you either a long explanation of why I love it so much or an analysis of it as a beautiful piece of poetry (and I'm more than qualified to do both). But time is short, so instead I will share the lines that I recur to most often and have, in other winters, at other times, through my cancer treatment, and through this pandemic: "He ruin'd me, and I am re-begot/ Of absence, darkness, death: things which are not."

It has been a year of cataclysmic global and small personal losses. It seemed sometimes that loss was only thing that could be around any corner. I think of death every day, whether it is my own, those in the news, the ones I fear for my parents, or the fast-approaching one of my companion animal. Even as I write this I am staying up late because Percy, my aged and beloved cat, has chosen to sleep on me and he's ailing so quickly that any time he does this might be the last, especially since I leave tomorrow for a 2-week stay in St. Louis. For me the risk of travel was worth the reward of a Christmas with my parents, who I have not seen for six months (since they came to take care of me after my surgery). The combination of their ages (81 and 76) and my cancer means that this could easily be our last opportunity.

I've said before that a year (or however long it takes to get this health crisis under control) is longer in my life than in most people's. But it does not mean that "absence, darkness, death: things which are not" don't haunt all of us. And though tonight and in the days to come we may sit through them at a vigil--for Lucy, as the poem's speaker says--we must know that she will be back. So I welcome you to wait with me, and to watch for the light.

Love,

Bex

A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy's Day

'Tis the year's midnight, and it is the day's,Lucy's, who scarce seven hours herself unmasks;

The sun is spent, and now his flasks

Send forth light squibs, no constant rays;

The world's whole sap is sunk;

The general balm th' hydroptic earth hath drunk,

Whither, as to the bed's feet, life is shrunk,

Dead and interr'd; yet all these seem to laugh,

Compar'd with me, who am their epitaph.

Study me then, you who shall lovers be

At the next world, that is, at the next spring;

For I am every dead thing,

In whom Love wrought new alchemy.

For his art did express

A quintessence even from nothingness,

From dull privations, and lean emptiness;

He ruin'd me, and I am re-begot

Of absence, darkness, death: things which are not.

All others, from all things, draw all that's good,

Life, soul, form, spirit, whence they being have;

I, by Love's limbec, am the grave

Of all that's nothing. Oft a flood

Have we two wept, and so

Drown'd the whole world, us two; oft did we grow

To be two chaoses, when we did show

Care to aught else; and often absences

Withdrew our souls, and made us carcasses.

But I am by her death (which word wrongs her)

Of the first nothing the elixir grown;

Were I a man, that I were one

I needs must know; I should prefer,

If I were any beast,

Some ends, some means; yea plants, yea stones detest,

And love; all, all some properties invest;

If I an ordinary nothing were,

As shadow, a light and body must be here.

But I am none; nor will my sun renew.

You lovers, for whose sake the lesser sun

At this time to the Goat is run

To fetch new lust, and give it you,

Enjoy your summer all;

Since she enjoys her long night's festival,

Let me prepare towards her, and let me call

This hour her vigil, and her eve, since this

Both the year's, and the day's deep midnight is.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

2020 Can Take My Hair, But Not My Hope

My hair started falling out on election night.

I thought at first it might be the anxiety, that I was literally pulling my hair out with worry over numbers I already knew were not going to be definitive before the night wore into morning but which I stayed up until 3:30am watching anyway. I tweeted rapidly, reassuring my jittery timeline that not only had we all known that the night would bring no results but that we had even expected Trump to lead in key states because of the greater number of mail-in ballots from urban areas that would largely count for Biden. We knew. We all knew. But we were all terrified, flashing back to 2016 and already dreading another four years of living life on high alert, in constant survival mode.

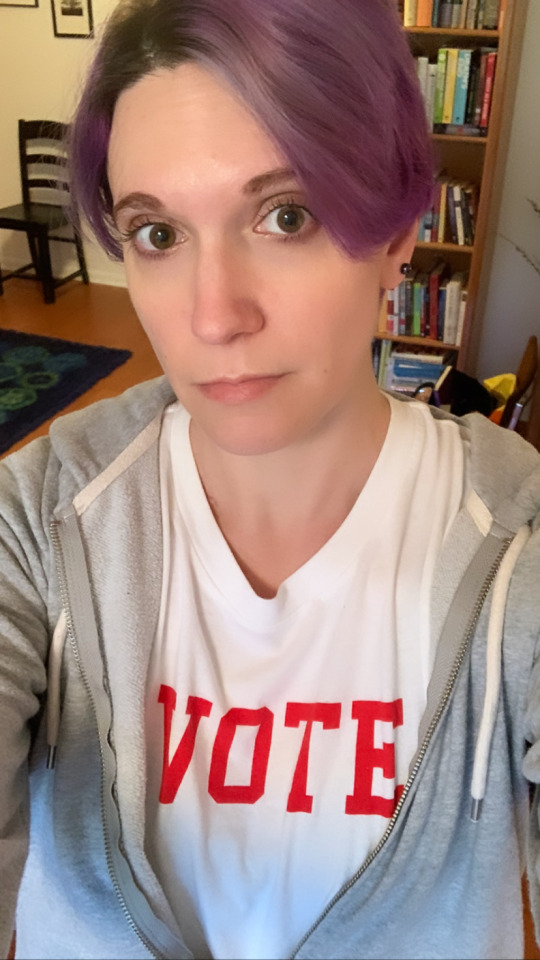

I posted a selfie with a tweet that read, "Could be the last presidential election I vote in (blah blah stage 4 cancer blah blah) and I wish it were better and clearer than this but it's a crucial privilege to have voted. Remember, whatever the outcome, the last thing they can take from you is your hope."

To me that last sentence has been a mantra for these years and for my treatment. I have consistently refused, despite overwhelmingly terrible odds, to lose hope. The story of Pandora's Box tells us that the very last thing left inside was Hope--that even once all the demons were out in the world there was that tiny, feathered creature left to hang on to. It hasn't been easy, but I am one of the most stubborn people you will ever meet (and if you doubt this just ask anyone who's ever fought me on anything!) and it has turned out to be a saving grace rather than an irritating personality trait. Feeling like the world was trying to take my hope away made me angry. And when I get angry I will fight back.

I know I'm not alone in feeling like we entered some kind of alternate nightmare timeline on election night 2016. To that point, despite periods of immense personal difficulty, nothing truly terrible had happened to me. Then, in short order, my marriage ended and I was diagnosed with and began being treated for a terminal illness, all against the backdrop of a regime so deliberately hateful that it was truly incomprehensible to me. Then, a global pandemic and national crisis swept away the small consolations I'd found in my new life with cancer. The temptation to feel hopeless was strong and I struggled with it, particularly in the isolation of quarantine. I'm struggling with it now, facing a winter of further lockdowns, social isolation, continued chemo, and the added indignity (and chilliness!) of not having any hair. But somehow the coincidence of my hair loss with election night seemed like a good omen for the future, if a sad thing for the present.

I heard the news that they had called Pennsylvania for Biden at a peaceful Airbnb in the Catskills after stepping out of a shower where lost hair in handfuls. It felt oddly like a sacrifice I had made personally. I joked about this with friends on the text chains that lit up and that (despite my promise to myself and my writing partner that we'd "go off the grid") I responded to immediately. Instant replies, with emojis and GIFs, participated in the fiction: "Thank you for your service!!!"; "We ALL appreciate your sacrifice!"; "Who among us would NOT give up their hair for no more Trump?". The feeling was real for me, though. It was as though the good news demanded some kind of karmic offering. You never get something for nothing, I thought, and really it was a small price to pay.

The rest of the weekend passed too quickly, with absorption in the novel I plan (madly, given that I also work full-time) to work on for "National Novel Writing Month" (NaNoWriMo), walks in the unseasonably warm woods, and nighttime drinks on the back deck under the stars, watching my hair blow off in fine strands and drift through the sodium porch light. My friend and I read tarot and both our layouts contained The Tower, the card for new beginnings from total annihilation, the moment of destruction in which (as the novel's title says) everything is illuminated. "This might sound dumb," he said, "but maybe yours is about your hair." It did not sound dumb.

[shaved heads, the 2020 election, and a couple pics under the cut]

There is probably no more iconic visual shorthand for cancer than hair loss. It happens because chemo agents target fast-proliferating cells, which tend to inhabit things that grow rapidly by nature (hair, fingernails), or that we need to replenish often (cells in the gut), as well as out-of-control cancer cells. But not all cancer treatments, not even all chemotherapies, cause hair loss. In my 20 months of being treated for cancer and my three previous treatments (four, if you count the surgery I had) nothing had yet affected my hair beyond a bit of thinning. This despite the fact that my first-ever treatment (Taxol) was widely known to cause hair loss for "everyone." I had been fortunate with this particular side effect in a narrow way that I have absolutely not been on a broader scale. "Maybe," I had let myself think, "I can have this one thing." The odds were in my favor too; only 38% of people in clinical trials being treated with Saci lost their hair. I liked the odds of being in the 62% who didn't. But--as we all felt deep in our gut while they counted votes in battleground states--odds aren't everything.

I had come to treat the "strength" of my hair as a kind of relative consolation (though as with everything cancer "strength," "weakness," and the rhetoric of battle have nothing to do with outcomes). I treasured still having it, not just out of vanity (though I have always loved my hair whatever length, style, or color it has been) but because it allowed me to pass among regular people as one of them. I had no visible markers of the illness that is killing me, concealed as first the tumor and then the scars were by my clothing. "You look wonderful," people would tell me, even when I suffered from stress fractures from nothing more than running or sneezing; muscle spasms in my shoulder and nerve death in my fingertips; nausea that I swallowed with swigs from my water bottle that just made me look all the more like a hydration-conscious athlete; and profound, constant, and debilitating fatigue. Invisible illness had its own perils but I would take them--take all of them at once if necessary!--if only I could keep my hair and look normal.

It was not to be. A part of me had known this, since a lifetime with metastatic cancer means a lifetime of treatments a solid proportion of which result in hair loss. But I had hoped. And I had liked the odds.

The hardest thing for me is having to give up this particular consolation before knowing whether or not my new treatment is also working on my cancer. Unfortunately, there really isn't a correlation between side effects like hair loss and effectiveness of treatment. If it is working then I will feel that--like the election to which I felt I had karmically contributed--it was all completely worth it. Yet, even in this best case scenario, there's a new reality for me which is that while I am on this treatment I will stay bald. When you are a chronic patient you hope for a treatment that will work well with manageable side effects. And if this treatment works--and if the other side effects are as ok-ish as they are now--then I will remain on it.

It's that future that I am furious about more than anything else. I want to continue to live my life, of course, but I don't want to have to do it bald! In part that is because I don't want to register to people constantly as an archetypal "cancer patient" when I know that I am so much more. It is also in part because I don't want to think of myself as being ill, and living every day having to disguise my absent hair will make that all the tougher. I have already noticed that I feel, physically, as though I am sicker because of my constantly shedding hair. How could I not, in some ways, when every move I make and every glance at myself (including in endless Zoom windows) shows me this highly visible change?

For that reason, I'm shaving my remaining hair tomorrow (Wednesday). It's a way to feel less disempowered--less like hair loss is happening to me--and wrest control of the situation back. I will try to find agreeable things about it: wigs, scarves, cozy caps, bright lipstick, statement earrings, and a general punk/Mad Max vibe that is appropriate to 2020. But I don't want anyone to think for a second that I find this agreeable, or even acceptable, or that I don't mind. I mind a whole hell of a lot. My hair was my consolation prize, my camouflage, my vanity, my folly, and my battle cry.

I dyed it purple when I was first diagnosed because I knew (or thought I knew) that I would be losing it soon. I didn't, and I came to cherish it as a symbol of my boldness in the face of circumstances trying to oppress me, to make me shrink, to tempt me to become invisible. I refused and used it to "shout" all the louder in response. Because of what it came to mean to me, I'm nearly as sad about losing the purple as I am about losing the hair itself. It both symbolized the weight I was carrying and also that I would not let that weight grind me down. It was my act of resistance and my sign resilience all at once.

I sent a text to my friends, explaining this and offering, as an idea, that I could "pass the purple" to them in some way, small or large. It would feel more like handing off a torch or a weight (or the One Ring) than anyone shaving their head in solidarity. (After all, if they did that it would just remind me as I watched theirs grow back that, in fact, our positions were very different.) You're welcome to do it if you'd like too, internet friends, with temporary or permanent dye or a wig or a headband or one of those terrible 90s hairwraps or whatever. But I don't require that anyone do it because I feel support from you all in myriad ways, all the time. (But if you do, please send me pictures!)

It's November 2020. The election is over and Joe Biden has won. I still have cancer and I'll be bald tomorrow. I hope it's a turning point, both personal and global, because it feels like one. We've given up a lot in the last four years and I cannot say that I feel in any way peaceful or accepting about having to give up yet one more thing. But in losing my hair I absolutely refuse to also give up my hope.

(On our walk we did also seem to find a version of The Tower, all that was left of an abandoned house)

#life update#my life as a cancer patient#stage 4#mbc#metastatic breast cancer#losing my hair#unfair things#election 2020#I just have a lot of feelings#the tower#us politics

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cancer Doesn't Respect Narrative

Or: Proof I Don't Live in Live in a Novel

[Originally posted October 3, 2020]

Hello friends,

The last time I updated here was while I was getting my August scans. I didn't share the results, didn't share my treatment plan, and didn't say that I got another set of scans on Thursday. (If you would like the news alone, please skip ahead to the section on "The News" at the bottom.) I know people want to know and I know this is the best way to communicate with you all. But I also avoid it, not only because I'm not used to the idea of purely informational blog posts (though that's true) but because I get just so incredibly tired of being a cancer patient.

I mean, of course I do. It's frightening sometimes and boring all the time. The treatments hurt more than the illness. And often--in my position and today--it's not possible to present anything hopeful or imagine an end to it. Cancer invades your whole life, not simply threatening you with shortening it considerably but insidiously taking over, displacing all the things you were, all the things you enjoy. I have resisted that as much as possible. I've continued to work (except for my leave for surgery) and to socialize (as much as it is possible during COVID) and to keep doing other things (like this weekend retreat I'm on right now). But every time I start to feel like I might be able to live as a regular person, to consider a "long term" beyond the next few weeks or months, I get bad news. And it feels like a rebuke for having allowed myself to hope.

It's not, of course. The news is neutral. The treatments that fail me (or that, in the language of clinical trails, I fail) don't know or care who I am or what's going on with my life. I don't occasion their failure and I don't deserve it. People who are treated successful also don't deserve it. Cancer is random and in its randomness it is cruel.

In its randomness it is also notably resistant to narrative. One reason I was holding off on updating here is that I not only wanted but truly expected to be able to post to say that I was getting better after my surgery. In one sense that is true. I feel very much better without my biggest and most scary tumor. For months (I don't even know how many) the first thing I would do every morning when I woke up was to feel the tumor and see if I could tell whether it had gotten bigger. Sometimes, I could tell. Now I have my reconstructed breast, living tissue that has no nerve endings so that I don't (in a strict sense) feel it at all, I don't have to touch it each morning because it will not have changed. The relief of that is indescribable. With that burden lifted--and the only visible marker of my cancer gone--I was feeling so much like a well person that I could not believe my scans would not show the same thing. That they didn't, and that I now have to leave this clinical trial to move onto yet another (fourth, for those of you counting) line of treatment in 20 months, was all the more shocking because I had allowed myself not just to hope, but to forget to think of myself first as a cancer patient.

I study narrative professionally. I consume it for a hobby. I produce it sometimes too. And so on some very deep level I think I expected things in my life to follow a more acceptable narrative path. Surely, after my suffering and after this big surgery, we couldn't expect me to not improve. What audience would accept that! Similarly I have joked before that it's unacceptable that no one, not even people from my past or friends who see me every day, has yet fallen in love with me. Having a life-threatening disease is supposed to come with that particular narrative payoff by rendering my vitality all the more poignant in contrast and/or making someone realize that they cannot imagine their life without me and confess their feelings. I've read the stories! (Of course, I do also usually die in those as a means of realization for the (male) protagonist so there's potentially an upside.)

In cancer stories, there are only two possible outcomes: you die or you don't. If you don't, you may write as a survivor, publishing a memoir that (in the case of breast cancer) someone will insist on giving a pink cover or sticking a ribbon on during the dreaded "pinktober" (welcome!), a month of "awareness" that is hell for most breast cancer patients. And if you do die, you may be published posthumously or live forever (or as long as the servers stay on) in blog posts like these about your "cancer journey" and a Facebook page now managed by your friends or family. The teleological (and obvious) movement of most memoirs towards survivorship is the reason I don't read them. If you give me one I will appreciate it as a sign that you care about me but I will not read it. I'm not headed there. Whenever it happens, however long from now it is, I will die from this disease. And while I may endure, even for a long while, I will never be cured. I don't make a good narrative prospect in this way, for anything I can tell you is as confused, miserable, outraged, and fragmented as I feel when I contemplate those facts.

Cancer doesn't respect narrative, so it's hard to make sense of it. I'm not able to do it here, or in my regular life. I did read one book, "The Undying" by the poet Anne Boyer, that captures the randomness, pain, enlightenment, cruelty, and terror of the experience of having cancer very well. It is a memoir of her treatment and aftereffects for her triple-negative breast cancer that entirely resists the track of most memoirs. It is more like a prose poem, and even while I was frustrated going through it and searching for the facts that would allow me to place her within my cancer frame of reference (what chemo regimen was she on? what trial did she join? where was she treated?), I appreciated it as an act of resistance to the genre.

I also appreciated that, like me, she was single (though with a teenaged daughter) and had to count on unofficial, unsanctioned kinds of love and support. As she writes:

“But the unexpectedly sick person—the one incapacitated in their body when they should have, in the accepted social order, been doing something else, like caring for their own children or caring for the elderly around them or going to work—must cash in their love me from the collateral of every or any temporal experience, calling in the past, playing on hopes for the future. Love me, the sick person in the prime of their life says, trying to look as if they will grow strong again, for what I have done before, and also what I might do, and also love me for the present in which I am eternally trapped, uncertain of my exact attachment to time.” (125-126)

“Cancer was hard, but I had these inventive forms of love to soften it, even if these loves were the completely extralegal and unofficial kind, unattached to the couple or family. But when I was sick I also felt the cold sadness of what would have happened if I was friendless or for whatever reason at that point unlovable, or what might happen to me when I became so.” (288)

I am "uncertain of my exact attachment to time" in that I am trapped not as much in the present as an always-uncertain future. I never feel so alone as when I contemplate my next treatment and try to anticipate how it might steal ever-more of my life, my time, my self. I cannot stand being a cancer patient any longer. But I don't have a choice--except to die and that is no choice.

The News:

For anyone who just wanted to skip to the news, here it is. My August scans showed, unsurprisingly, that while I was out of chemo for surgery my cancer grew in some spots (my lungs) but not others (my liver) and appeared in a new spot on my T2 vertebra. That wasn't awful, in terms of what was expected, so I picked up again with the chemo + immunotherapy.

I got a call at 5pm on a Friday, which is never a good sign and it wasn't. The scans I had Thursday showed growth in the lungs, a new spot on the liver, and (worst) several new spots on the bones near the T2 (T3, sternum, scapula). In fact, it showed that those new spots had weakened the bone enough that I'd fractured the sternum and scapula, probably a few weeks ago. I worry that this means it's the more aggressive metaplastic cancer.

A note on broken bones: those of you who recall my adventures with my stress fracture in my spine (from running) know it doesn't take much to do this. When your bones are brittle normal activities are enough. I could, potentially, even have done this by sleeping on my right side. And, if you want to know, YES it is painful. I just thought that I had pulled a muscle because I was shifting my weight right while trying not to put too much stress on the left side post-surgery. And that's probably what did happen...except that instead I fractured it. So now I have to try to keep my right side still while also not hurting my left post-surgery side while...living alone. During a pandemic. Who wants to come pick things up for me?! Anyway, it doesn't feel awesome but now at least I know enough not to keep it still as much as possible. (I made a sling out of my own sweatpants of which I was inordinately proud...photo attached.)

Back to my results. That's enough growth that I have to leave the clinical trial, which they mandate so that you can get the most effective treatment possible which, they determine, doesn't come from their drugs. I understand that, but it also feels like getting kicked off for bad behavior. I'm meeting my team this week to figure out what's next. The treatment I will probably go to next is one I have considered before and that, in fact, I'd tried to get through a clinical trial before it was FDA-approved, IMMU-132. One good thing about it is that I can get it in Princeton (I think) and not have to arrange rides to and from Philadelphia (since no guests are allowed at the hospital). What I don't know, though, is how I'll deal with the side effects. We've sort of reached the end of my minimally disruptive treatments roster, though of course it all depends on the person and perhaps I will be lucky with side effects. As with so many things, I'll just have to wait and see.

I do hope, though, that I'll be able to get back to some parts of my life that allow me to be anything but a cancer patient. I'll try to share some of that here too, since perhaps it's just as interesting to know about as my treatments, but if I don't I'm sorry for the silence. Because this isn't a novel, I don't get to get better (yet). And because I don't get a break from being a cancer patient, I don't always have the energy to talk about not being better yet. I also worry about exhausting the people who care about me with bad news, or even being made to endure an optimism which isn't exactly unfounded (because we don't know what will happen) but in which I cannot share.

I'm sorry this is not the post it should be by narrative convention. But thank you for reading anyway and for sticking with me during what I can only imagine is a disheartening experience for you too.

Be well and be kind.

Love,

Bex

#treatment update#october 2020#my life as a cancer patient#covid and cancer#clinical trials#metastatic breast cancer#mbc#stage 4#triple negative breast cancer#tnbc#my face

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Better Living Through Surgery: Life with Less Cancer!

[Originally posted August 13, 2020]

Hello from Penn Hospital!

Not to worry - I haven't been here the entire time since my last post, although I did end up spending an entire week in the hospital. Right now I'm sitting in the outdoor section of the cafeteria, which might be a mistake given that I'm not allowed to eat anything until after my CT scans at 1pm. The CT scans are part of my preparing to resume treatment for the rest of the cancer that's still in my body. The last time I had chemo was June 23rd and I've now hit the sweet spot of being a month past my mastectomy (so, mostly recovered) and out of other treatment long enough that I'm not suffering side effects any longer. It feels...almost like I don't have cancer at all.

Two Surgeries for the Price of...Two!

Let me back up a bit to the surgery though. I'd like to report that everything went totally smoothly...and it sort of did! Except that I had to have two surgeries because it also sort of didn't. As usual, what happened to me was super rare (less than 1% of cases!) and I would like to submit a formal retraction of any wishes I had to be exceptional. I've read "The Monkey's Paw." I know to be careful what I wish for. (Although, actually, I'm lying because I still plan to be the exception to the median life expectancy of those with my particular type and stage of cancer. If I have to be in the 1% of cancer cases it ought to be a good thing at least once.)

I had two surgeons for the two parts of my first surgery: one for the mastectomy (removing that incredibly stubborn initial tumor) and one for a "flap reconstruction," which used my own tissue (from my stomach - free tummy tuck!) to build a replacement. When they do that second part, they also take a blood supply so that a substantial part of it is vascular surgery. The reason that the reconstruction ever fails is if something goes wrong with the blood supply. If that happens, it's nearly always (99% of the time!) within 24 hours. What happened in my case was that everything went well with the surgery, even though it took about 7 hours, and I was recovering well and quickly. I was set to go home after my third night in the hospital (so, on Thursday).

Overnight on Wednesday, however, something went wrong with the blood supply. The new tissue was filling but not draining. What they later learned, once they rushed me back into the OR, was that the vein in it had a blood clot. They were able to fix it by taking a vein from my ankle to replace it. So basically that reset the clock on my recovery so that I ended up having to stay an additional three nights, going home on Sunday. (My initial surgery had been on a Monday.) It's actually extremely lucky that I was still in the hospital, despite how sad I was at having to stay. If I had been at home, far away from experts and surgeons, the tissue probably would have died and the reconstruction would have failed. It was a close thing since I was set to go home.

Anyone who has ever been in a hospital doesn't need a reminder of how, despite everyone's best intentions it is pretty terrible. I hadn't spent a night in the hospital since I was a newborn, despite all my various treatments, so I didn't know. Now I do and I never want to go back. The hardest part is that they have to wake you up almost constantly for vitals and to assess how the blood supply is doing (listening for arterial and venus sounds). For the first day after each surgery this was every 30 MINUTES, then every HOUR, then finally (on my final night) every 2 hours. And I'm the kind of person who's AWAKE as soon as I wake up. So I essentially didn't sleep more than an hour at a time until the bitter end when a nice nurse got a nice doctor to give me some kind of sedative so that I was able to sleep through the checks. I don't have a kid, so let me just say that this level of sleep deprivation was like nothing I had ever experienced. I see why the CIA used it as a form of torture. I'm a veteran of being tired and of many different kinds of fatigue but never have I been unable to get into REM sleep for so long. I am eager to avoid it at all costs again.

I had been more worried about the boredom than the lack of rest (because, at least on paper, the hospital seems like a place where you would mostly be resting/recovering) and it was indeed very boring. I was SO tired that I wasn't able to really do anything like read a novel, knit, or even really watch TV. I did binge a few podcasts, return to some more "Buffy," and attempt to chat to my parents when they could be there. The COVID visitor policy made it even more isolating and lonely than it would usually be. I was only allowed one "designated visitor" per day so my mom and dad switched off on who that was. Visitors could only be in the room and, once you left, you were gone for the day. So, for example, it's not like my mom could say hi in the morning, pop out and get us lunch, and then come back. All visiting was consolidated for the day. That meant that I tried valiantly to be good company for a few hours, but I imagine mostly I was too exhausted to accomplish that.

I took laps around the hallway (in my mask), which was actually a big achievement especially given the four surgical drains that I had (and left the hospital with). It's amazing how quickly you can lose conditioning in your muscles...and also how exhausting it is for your body to have been, essentially, assaulted and be dealing with wounds. That said, I've been super impressed by my body's healing capacity. I got the drains out within a week for one set and 10 days for another. After that, it was much easier to feel like I was healing and returning to normal. I'll have to rebuild my abdominal muscles, since that part of the surgery involved cutting them (and a new hip-to-hip "smile" scar), and for now I still can't bend all the way over, stand up totally straight (did I ever?), or lift anything heavier than a gallon of milk (because of the reconstruction). I'll probably need some physical therapy, but the ability my body has shown to heal is incredible.

Also incredible is the difference it has made to my mood and anxiety. In the hospital, they kept asking me for my pain number (which is kind of a useless exercise anyway, in my opinion) and I kept sort of shrugging and saying "2? 3?" to their disbelief. After all, I had open wounds! I had two major surgeries! But the pain of the tumor itself (and especially of the fluid-filled cyst on top of it) had been constant, increasing, and worrying. The pain of the tumor had meant my treatment was failing me and that my cancer was getting worse. The pain of the surgery meant I was healing so I embraced it. I still get tired more easily than I expect and am sure that the recovery period for this is going to turn out to be longer than I anticipate. But it is a huge relief.

That Bastard Tumor

Now, sadly, they don't actually save your cancerous tumor for you to look at after the surgery. (Honestly sad about this. I wanted to look it in the eye!) But they did send it off to a pathologist. The results made me feel very vindicated in my persistent sense that something about this bastard of a tumor was just DIFFERENT (and worse). They found that it had areas in it that were metaplastic, meaning (essentially) that the cells are hybrid, aggressive, and chemo-resistant. Here's what Johns Hopkins has to say about it:

"Metaplastic breast cancer is a rare form of breast cancer, accounting for fewer than 1% of all breast cancers. It differs from the more common kinds of breast cancer in both its makeup and in the way it behaves.

Like invasive ductal cancer, metaplastic breast cancer begins in the milk duct of the breast before spreading to the tissue around the duct. What makes a metaplastic tumor different is the kinds of cells that make up the tumor.

When the cells of an invasive ductal tumor are examined under a microscope, they appear abnormal, but still look like ductal cells. Metaplastic tumors may contain some of these breast cells, too, but they also contain cells that look like the soft tissue and connective tissue in the breast. It is thought that the ductal cells have undergone a change in form (metaplasia) to become completely different cells, though it is not known exactly how or why this occurs.

Metaplastic breast cancers can also behave more aggressively than other kinds of breast cancers.

Metaplastic tumors are often, though not always, “triple-negative”, which means that they test negative for estrogen and progesterone receptors, as well as for the HER2/neu protein.

Metaplastic tumor cells are often found to be high grade, which means that they look very different from normal cells and are dividing rapidly.

Metaplastic tumors are, on average, larger at diagnosis.

More often than in other kinds of breast cancer, women with metaplastic breast cancer can have metastasis (when the cancer has spread beyond the breast) and may be more likely to recur (come back later in another part of the body)."

Sounds familiar, right? I can tell you, it feels good to get that out of my body! I want to be clear, though, that it was only **some** of the tumor that was this nasty metaplastic cancer. It was, as I described it to the amusement of my surgeon, "like chocolate chips in ice cream." (Way less fun than chocolate chips, obviously.)

That is actually good news too, because it means that there's a pretty high chance that the metastatic sites are NOT this nasty form of cancer. It wasn't noted in the original biopsy back in January 2019, nor in the spinal tumor biopsy in Feburary 2019, nor in my biopsy from July 2019. Metaplastic cells are fairly distinctive so they would have been noted if they were there. At some point, metaplastic regions appeared in the bastard tumor, probably a reason that it stopped responding to treatments that worked elsewhere (including PARP inhibitors and the chemo/immuno combo that I'm currently on). If those treatments, or others, can work on the remaining sites that are NOT metaplastic it becomes much more possible to imagine living with this as a chronic disease. We won't be able to tell until I get today's scans and we see how the next 8ish weeks of treatment go. But still, I think cautious optimism is warranted.

Resting and Recovering

My parents were able to stay with me for another 10 days after I went home and it was so wonderful to have them taking care of me. It made me realize that, actually, I have done the bulk of this cancer treatment without that particular kind of support. I mean, I knew that intellectually, but the difference between having someone looking after me and not was something I almost couldn't fathom on an emotional level. They lived with me for the first 3 months after my diagnosis in 2019 but--thanks to how long was spent getting various tests and seeing doctors--that only included a few weeks of chemo. They would obviously have stayed longer--would be glad to drop everything and rush out whenever I want!--but it's been my choice to continue as much as I can with my "regular" adult life. Being forced not to try was actually quite a favor to me. I'm left with a lot of thoughts about how I ask for help, offer it, accept it (or don't), and how I feel about it. I'll save those for another time, though, and just thank both my parents and my wonderful and tireless group of friends for giving me their support in whatever ways they can.

It's almost time for me to go drink some delicious barium and get a CT (bringing me a couple steps closer to lunch), so I'll just conclude by saying that I felt so good post-surgery that I forgot, for a while, that I still had cancer at all. After all, it was that tumor that I could actually see and feel and that was causing me daily pain and anxiety. Taking it away felt like taking away all the cancer. But, of course, it's still there: in my lungs, my lymph nodes, my bones, and my liver. It's a systemic and chronic disease, but I do at least feel more like I've been given a fighting chance again.

Hope you're all doing as well as can be right now. Be well and be kind.

Love,

Bex

#my life as a cancer patient#treatment update#august 2020#covid and cancer#mastectomy#metastatic breast cancer#mbc#stage 4#triple negative breast cancer#tnbc#clinical trials#scanxiety#metaplastic cancer

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In haste: I'm having surgery now!

[Originally posted July 12, 2020]

Hi friends,

I mentioned at the end of my last post that I'd be having surgery: well, it's tomorrow (or today, depending on if you read this Sunday or Monday)! Or rather, it's in about 12 hours. In fact, I only have one hour left to have any food I want before I go under so that's one reason I'll need to be quick. The surgery itself is a single mastectomy, which didn't make sense in the past but which does at this point. As I mentioned, this current treatment--like the one before it--proved to be effective at keeping the metastatic sites stable (no new locations, no clinically significant growth) but not at all effective on the main tumor. That means it makes sense to do a more localized treatment and, long story short, that treatment is taking the whole thing out.

It's a radical step, but in a way one I am very prepared to take because at least it will be something very clearly proactive that is likely to make a difference to my quality of life; the tumor hurts all the time and its presence causes me constant anxiety, not to say great distress.

It's a big surgery, especially since I'm having reconstruction at the same time. Since I had worried that this wouldn't even be possible due to the size of the tumor and the amount of skin that will have to come off with it the whole thing ends up feeling "lucky," though only in context. (The breast reconstruction I'm having is "autolocus reconstruction," which means using your own skin instead of an implant to rebuild the breast. The skin comes from my stomach which, as I told the doctors to their bemusement, is great because that's where I keep ALL my fat!)

I'll be under for about 5 hours, with four surgeons working on it, and in the hospital for the rest of the week. The recovery time is 6-8 weeks. So...it's kind of a big deal! I'm scared, of course, but eager to get it over with. My parents have both flown out from St. Louis and are here to support and help me for the next couple weeks. It's wonderful to see them since the 6 months we've spent apart has felt longer than usual. One of us will, I know, update you when we can.

Be well and be kind,

Bex

#my life as a cancer patient#treatment update#july 202#covid and cancer#mastectomy#metastatic breast cancer#stage 4#mbc#triple negative breast cancer#tnbc

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Hardest Thing in this World is to Live in It."

I wish I could be your good news

[Originally posted June 25, 2020]

Hi friends,

It's been a long time since I've written here, though with all that's going on in the world I was genuinely unsure if had been months, weeks, or days. Time dilates each day while the days somehow pile up into months. It's actually been about 6 weeks, during which time I had more scans that showed that my primary tumor is still growing.

It's really a stubborn bastard, isn't it? As before, the treatment I've been on has been relatively successful on the metastatic sites (no new locations, some regression in size overall), but the breast tumor itself just keeps getting improbably larger like...well, like a cancer.

On June 1st, the day after I got my most recent news, I posted on Twitter and Facebook to say this:

"Thank you to all of you for liking this and sending your messages of support, both privately and in public. It's hard sometimes to remember in the dual isolation of quarantine and illness that there are so many kind people in the world wishing me well: a bright light in dark times.

I'll post more about it when I'm able, but I am ok given the situation. My latest scans showed that my cancer is still growing-my 3rd failed line of treatment in 15 months. Good things: metastatic sites stable, no new ones, still approaches to try. But optimism is hard right now.

In my cancer group, we talk about "toxic positivity," the pressure to present news w/the best possible spin and be a model patient who determinedly soldiers on. I tend only to post when I can do that. Right now, going on feels impossible. I am so lonely and so tired.

It's not just cancer, though it's quite a burden to carry. Things are bad in the world. Worse than I'd ever imagined. And I am tired of having cancer. But I will never be done while I'm alive. There are burdens we can't put down. It's ok not to bear them cheerfully, for you too.

Addendum: I also feel (absurdly) like I let people down personally when I don't improve (a thing over which I have zero control). In addition to wanting to be better, I want to be your good news, to give us all something to celebrate. I know it's untrue, but it's compelling anyway."

So that's how I've been feeling. I've been wishing, over and over, that I could be your good news, could give you something positive in the midst of all this horror. The fact that I can't turns me quiet and exhausts me in a far more profound way than the ongoing side effects of chemo. I just had my 8th chemo treatment - my first was on January 30th - so that's been 6 months of chemo while working full-time. I didn't realize how burned out I truly was until I used some vacation days (which I had been rationing for hospital days and side effects) for an actual vacation.

It's all more than enough, in combination with all the events going on in the world, to weigh me down. Not only because I do feel, quite literally, weighed down by a tumor that is 8cm x 6.5cm (think of it as a large orange or small grapefruit), but because the heaviness of just continuing to live each day as the pandemic worsens across most of the U.S. and the prospect of ever resuming the still-good life that I was able to manage with cancer--full of things like travel, going to my job, seeing groups of friends, dating, and bars and restaurants--dwindles to almost nothing.

A year in quarantine is a terrible prospect for us all, but a year is longer in my foreshortened life than it is in most of yours. I've become unsure how to continue to live with that, to confront it every day and feel angry that nothing is seemingly ever getting better. I'm actually a fundamental optimist, despite it all, but sometimes enduring, surviving, and keeping on is overwhelming. I just want to be better. I just want not to be alone. I just want to go back to normal. I just want some good news. Preferably, I would like to be that good news.

The quotation in the title of this blog post is, as I know many of you will have recognized, a quotation from "Buffy." (Sidebar: I almost never used the long title when referring to the show, leading one of my UCLA undergrads to inquire once in class, "do you mean the Vampire Slayer?" and yes, UCLA student, yes I do.) I've begun rewatching (or re-re-re-watching? I don't even know at this point) my favorite season of the show, the sixth, which is many people's least favorite.

**SPOILERS** for a show that began airing in 1997 and a season that ran 19 years ago.

It's my favorite because it is an entire season about loss, deprivation, grief, and trauma. The quotation is the last thing that Buffy says to her sister before she takes the swan dive that leads to her death at the end of Season 5. Her death is meaningful, saving the world and preventing the apocalypse. Yet, at the start of Season 6, Buffy is brought back to life (and to a different network) by friends who claim it's because they believe she is in Hell but whose secondary motivations (their own inability to survive without her) are revealed over time. We soon learn that she was not in Hell (how could she be?) but Heaven (or a "heavenly dimension"). And like Milton's Satan and Marlowe's Mephistopheles, the deprivation that she knows, having been at peace, makes living each day painful.

As Buffy herself says in 6x03 "After Life" (to Spike, the only one she is able to go to for solace): "Everything here is bright and hard and violent...Everything I feel, everything I touch...this is Hell. Just getting through the next moment, and the one after that...knowing what I've lost ...They can never know. Never." Buffy becomes not the hero she has been for five seasons, but the anti-hero who is no longer able to be what her friends (and the viewers) demand of her: the same. She is profoundly changed, alienated from nearly everyone by the fundamentally incommunicable nature of her pain.

I have never identified with a character more than when, a few episodes later in the beloved musical episode "Once More, With Feeling," she pummels the villains of the day while spouting cliches: "Where there's life--" PUNCH "--there's hope! Every day's--" KICK "--a gift! Wishes can--" JAB "come true! Whistle while--" PUNCH "you work...so hard..all day..to be like other girls. To fit in this glittering world." It's a perfect literalization of the metaphor for fighting depression. (Literalizing metaphors is something the show always did especially well from its very first episode: high school is hell.)

I feel like this now. Kicking and throwing punches and struggling to make it look effortless, which it most certainly is not, fighting to remain here because the other choices are not really choices. "The hardest thing in this world is to live in it." The line is thrown back at Buffy by her sister at the conclusion of this show-stopping number, only it is now invested with new meaning. We now have more of a sense of how profoundly difficult that can be. How much we must struggle. And Buffy does struggle and she does fail. And that's why many fans dislike the season.

But I see in her struggles and failures the resilience of someone who continues to fight to stay in the world not because it is good, but because it is enough. The hardest thing in this world is to live in it.

So what will I do now? It's looking very much like I will be having surgery, possibly as soon as within a few weeks. The sheer size of this tumor and its resistance to other treatments make removing it a better option than it has been in the past. There are more details, of course, but I will share them later when I'm not exhausted from chemo. In the meantime, I am going to watch more "Buffy," and so should you.

Be well and be kind.

Love,

Bex

#my life as a cancer patient#treatment update#june 2020#covid and cancer#quarantine life#clinical trials#metastatic breast cancer#mbc#stage 4#buffy the vampire slayer#btvs#once more with feeling

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to bear the unbearable?

Quarantine week 9, chemo week 15, cancer week 67

[Originally posted May 14, 2020]

I was hoping to write a longer, more thoughtful post about how heroism is boring, day to day, and how ill prepared we are for what it looks and feels like. And hopefully I will! But since I know that it's been a while since I've posted about how things are going, I thought I'd at least catch up those of you who don't follow me on Twitter.

The format makes it easier for me to write briefer updates there, but tonight I wrote more than Twitter usually likes to see about how I feel about my next chemo visit tomorrow (May 15th), which is my sixth on this (3rd) treatment course and the last before I get another set of scans. It's also the 3rd since quarantine began (I snuck one in on March 12th when I was still allowed a companion for the trip instead of chauffeurs). Here's my Twitter thread about it:

"I have chemo again tomorrow bc even though time is a construct I still have to go every 3 weeks. My emotions are all over the place. Most simply, I am tired & don’t want to go through this again. However, it’s some of my only human contact so I’m also oddly excited.

I don’t mean physical contact (which is minimal & as distant as possible) but sharing space w/another person in silent company. It’s an exceptional circumstance so friends will drive me or sit on my (9 ft) sofa. I want to weep with relief about it, but also I’m angry. (2/)

Why am I angry? Well, first we all are. This situation is outrageous, unbearable, & yet we must bear it. Second, I live with & suffer from cancer all the time not just every 3 weeks. I’m wracked with guilt & sadness about how much I need my people around me yet cannot ask. 3/)

I want them to make exceptions for me more than once or twice every 3 weeks. I don’t want to ask, though, bc many of them feel stressed by compromising even this much. They cry when they tell me they wish they could be here or, if they are, that wish they could hug me. (4/)

I have to talk my parents (80 & 76 w/an underlying condition) out of traveling to be with me & suspect & worry they will do it anyway. Of the 504 hours in 3 weeks I spend conservatively 480 alone (& I’m awake for probably 350 of them). It’s unsustainable, unbearable. (5/)

This is what I’m doing to help stop the spread. Living by myself w/stage 4 cancer, working FT, spending 160 hrs a week alone, excited for chemo so I won’t be. I’m angry that more is not offered me. But I’m furious that others don’t have more perspective on their own suffering.6/)

I have been doing this for 9 weeks. 9 weeks is more time in my lifespan than it is for most of yours. Do not take away another 3 months, 6 months, a year or two from me. I do not have that much spare time. I know it is unbearable, but please bear it a bit longer. (7/)

But also: if you do see me (or anyone) walking with a friend or sitting together in the sun, do not assume we are being irresponsible because we are young or because one of us has purple hair. You have no idea what people are bearing in private. Be cautious, but be kind. (fin)"

These past few weeks have felt strained for me too. Mostly I've been doing what everyone has been doing and just trying to get by, enjoying the sunshine when we have it (although it's been spitefully cold and rainy for spring), reading and watching TV, throwing myself into work (especially if it benefits other people), and burning myself out on video calls seeking connection.

When I'm at my least generous, I resent other people (including those I know and love) for only having to endure quarantine itself, or for getting to endure it with someone who loves them and whom they love. I resent the idea of the nuclear family that sanctions a group of 4 seeing one another in one instance, but which makes my friends (living in 1s and 2s and also isolating) feel that they cannot see me. I resent the idea of couplehood that makes me feel that what I'm enduring is somehow a just punishment for my singledom (already viewed as a defect). I feel these resentments, but then I remember to be kind, which is the braver and better thing.

But it cannot be denied that going through this with cancer, as I do every moment of every day not just when I have chemo, is worse than doing it without cancer. If I am quiet on here, or bad replying to texts, or not able to do another Zoom call, it may be because the situation is quite literally exhausting me. It is taking me longer to bounce back from chemo sessions than it used to (now a full week) and I am not able to tell whether that is because of the cumulative effects of the chemo drug (which I was warned about) or because of the psychological drag of the quarantine. I also now find that I can't even really talk on the phone after chemo--that my energy levels are so depleted that only the comfort of having another person around physically works for those worst couple days. It's hard to have the capabilities of your body cut you off from what might be psychologically nourishing.

Thank you, though, for all the good wishes and messages you send from afar (which, now, is nearly anywhere). They absolutely make a difference, as I check my phone repeatedly and incessantly to make sure that, really, I'm not as alone as I may feel. I hope that you are doing as well as you can be doing too, and that you are finding comforts where you can.

Love,

Bex

#my life as a cancer patient#treatment update#may 2020#covid and cancer#quarantine life#metastatic breast cancer#mbc#stage 4#my fast-paced life#triple negative breast cancer#tnbc

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Endure: Cancer in the Time of Pandemic

[Originally posted March 28, 2020]

Hi all,

Welcome to a very special birthday post from me in which I mostly think about what it's like to have cancer in the time of a global pandemic. As a way of topping my last year's celebration--where I was just about to start chemo--this year the world is sheltering in place under quarantine orders as an unprecedented public health disaster unfolds around us. (Sorry if my prediliction for dramatic narratives is in any way responsible for this fact...)

I've been trying to work up the energy to post and let you know that I'm doing ok in this time of a global emergency...as ok as anyone I guess. I should say right off the bat that I am not, right now, immunocompromised, although I am at risk for it. We can all hope my system keeps bouncing back as it has done to keep me out of the most vulnerable group. (I do also have lung tumors, so a respiratory infection would automatically come with complications.)

Mostly, I spent a lot of the past two weeks wondering not if but how the pandemic was likely to affect my cancer treatment and I finally have enough information to confirm that, as of now, I'm still able to stay on the study and get chemo as planned this coming Thursday (April 2nd). I had been scheduled to get CT scans on Tuesday, March 31st to assess whether the treatment I started at the end of January has worked well enough for me to continue on the clinical trial. Although I get so many that it has perhaps come to seem routine, "scanxiety" is a very real phenomenon because these are how you learn whether things are going well (or well enough) or whether the disease has "progressed" and you have to regroup and try again with a new treatment plan. It had been since October that I had had a positive scan, with November showing a halting of improvement and December and January documenting the reversal of recovery. So obviously I was anxious and wanted them as soon as possible.

Hearing reports of "non-essential" treatments being canceled, my Penn oncologist and I decided to try to move my scans up. After many phone calls and the efforts and good will of a number of doctors and hospital staff I was able to get them on the 23rd in Princeton (avoiding both the drive into Philly and the potential for exposure there). I'm glad we did because I learned yesterday that the treatment has been working fine; not great, but well enough that a) some tumors got somewhat smaller, b) no tumors got bigger, and c) no new metastatic sites were observed. Clinically, that's ruled as "stable disease" b/c in order for it to be a "partial response" you have to have your cancer go down by at least 30%. But reversing the trend of growth is still a win, and perhaps more time will see more results. And crucially, I do not have to investigate a new treatment option or try to change in the midst of what is soon to be the crest of the pandemic wave of cases. It's only relatively lucky, but I will take it!

I have also seen reports in the cancer community about people having their chemo canceled as non-essential, which was shocking to me. I wrote last year about feeling like cancer should always be a "red ball" case that gets rocketed up the chain for testing, insurance approval, etc. and being shocked that it just wasn't. I understand that in some cases where a cancer patient is immunosuppressed, even attending a treatment at a hospital may pose greater risk than delaying it because the risk of infection is such a threat. But that is an extraordinary statement to make, amidst a daily barrage of extraordinary statements. Not all the stories were that clear-cut, though, so I was glad to hear from my doctor that as a stage 4 patient my scheduled treatments will not be bumped. I cannot have any visitors (and it's a pretty rough thing to do alone), but I can and will get through this. We all will. Because we all have in us more than we know.

***

Shortly after my beloved grandma died (suddenly, from complications during surgery) my dad told me that one of the last things she said to him was that she would be ok because, "I'm a warrior." And she was. From a tiny place in the woods of east Texas, as a teenager she ran her family's store during the Great Depression and cared for a mess of brothers. When my daddy was eight years old, she and my grandfather picked up and moved away from a community where they knew everyone and had for generations to Dallas--an unfamiliar big city--because his younger brother had been born deaf and they wanted to send him to a special school. She founded and ran her own school, an income she supplemented with other jobs while my granddaddy was away walking pipeline for an oil company.

When I knew her, late in her life, she had lost her sight but continued devouring books on tape and listening to the clues on "Jeopardy!". I was the first and only grandbaby and I was adored (not to say spoiled). The only times she actually saw me, before she was blind, I was just a few months old, chewing clean laundry in the basket in which someone had deposited me. As I grew up, she would feel my face, my hair, my ever-increasing height (and joke each time that "I'm going to have to saw your legs off!"). She would listen to my voice on Sunday phone calls; do crossword puzzles with me, as I read clues while lounging on her velour sofa; offer a "piece of Hershey" or a stick of spearmint gum from the same blue tin on the table in which she kept her cigarettes.

She could still piece quilts by feel, even though she couldn't see the fabric, and advised me on the 1ft patchwork square I made for my doll's bed. She was weakened, exhausted, blind, and often in pain (which she tactfully never mentioned with me around). Except when she changed to a polyester pantsuit for visiting the doctor, she wore carpet slippers and housedress with a pack of Marlboros in the pocket that she lit from a gas burner, leaning on her walker by an ancient stove. No one knew quite how old she was when she died--our best guess is eighty-three--because she was also the kind of Southern lady who told no one her real age. She was a warrior in that, despite all that had happened in her life and all that was happening to her body, she kept on going. She endured.

When I search for inspiration to continue with treatments that make me feel worse than the disease, to fight so hard to save a body that's betraying me, to stay in an increasingly terrifying world that's betraying all of us, I think of her last words. I'm a warrior. I will endure.

Believe it or not, you are also and you will too. In our struggles to continue with our lives in the face of monumental uncertainty and paralyzing anxiety, our greatest achievement is to keep on going. We fight (each of us different things) so that we may endure. It is not pleasant. It will reduce you to tears. You will exhaust all your emotional resources. But you will triumph. I have been fighting, existing in crisis mode, for 14 months and that is how I know that you can do it. You must grieve (and allow yourself time for it) for what you have lost, including a sense of safety or normalcy. But as you press on, you will find that inner strength or resiliency. I'm sorry that this is being demanded of you. It is not fair. But that will not change it. You may grieve, cry, fight, and struggle but, ultimately, you will accept that your way forward, your treatment, is to endure.

I've reflected a lot on social media about how living with stage 4 cancer accidentally prepared me for the experience of the pandemic. I wrote a coda to an essay that will be published--likely this May--about the "Body as Data." Since the coda itself will probably change by then, the situating evolving as rapidly as it is, I thought I would share it here. Thank you for being with me and providing that community that has been the saving grace of treatment.

Love,

Bex

***

As of writing this essay, it’s been 14 months since my diagnosis. I have tried three different treatments, two of which were clinical trials, one of which I am still enrolled in. It is approaching my thirty-sixth birthday [it's actually today - March 29th] and everyone is sheltering in place because of the coronavirus. I have lived more than a year now tolerating the same kind of existential uncertainty and fear of an alien invader in the body that the world as a whole is now experiencing. I have played my own doctor, watching my body for signs that a treatment is working, or that it is not, in much the same way. I have tried to anticipate what will happen if I become immunocompromised (as I currently am not, but am at risk for) and given up many of the pleasures that made my life better before (traveling, going out with friends) in the name of my health. I have offered my body up as data to research scientists with the goal of furthering not just my own treatment but the survival prospects of future patients.

I did not know that throughout this year I was in training for a time when we would all of necessity be regarded as bodies with the potential to produce valuable data about the spread and effects of COVID-19. We are starved for numbers, for data on infections and recoveries and for statistical models that may relieve us of the uncertainty we feel about the future. I cannot provide that. But I can tell you to be cautious readers of data and statistics that speak with any pretense to authority right now, even though I crave them too.

Cancer is invisible and so are viruses. This particular virus can inhabit the body but produce no symptom and live for days on surfaces. It may be in us. It may be in those we love. We are in the middle of the data. We are the data.

Susan Sontag wrote in Illness as Metaphor that “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place” (3). A pandemic transcends borders but does not do away with the kingdom of the sick. As someone already resident, I can say to you: welcome. The hardest thing about being here is the grief for what we have lost, including a sense of normalcy. The best thing, though, is what we may find: community in a time of crisis.

#my life as a cancer patient#clinical trials#covid and cancer#quarantine life#mbc#metastatic breast cancer#stage 4#my family

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m still here!

Hello, followers of my sideblog where I talk about my cancer treatment! I stopped cross-posting between here and my IRL cancer blog for friends and family b/c I just felt overwhelmed with the idea of too much communication. I regret that, though, since the Tumblr community has been so supportive and such a source of positivity and the good kind of distraction.

With that in mind, I’m about to reblog the missing updates (since March...this was also fallout from covid/quarantine) with the dates they were originally posted to catch you all up. After that, I plan to cross-post again.

Sending you all love,

Bex

#I'm still here!#reviving this blog#tumblr friends#tumblr life#my life as a cancer patient#blog things

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lost Weekends: Chemo Progress Report

Hi friends,

I'm writing you from my sofa, where I spend an increasing amount of time (much to the delight of the cat), at the end of my second post-chemo weekend. My last update was a month ago, right after I had done the considerable work of enrolling in the clinical trial at Penn that looks at treatment with chemotherapy and the immunological agent atezolizumab vs. just chemotherapy. My first session was on January 30th and I had a bit of good luck (for a change) and was randomized to the arm of the trial that got both the chemotherapy agent and the immunological agent, rather than the control group! (That's why I look improbably happy about my IV infusion in the attached photo.)