Welcome Earthlings! Within this digital environment you will find theoretical, practical and artistic information regarding the planetary perspective. We share our research on this website and provide useful information about the curation process. Click on one of the links below to discover more about planetary awareness. - the Planetary team

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

About us

The Planetary awareness event was conceptualised in the frame of the Masters program Arts and Society. Within the Thinking Arts and Society course and under the supervision of Sigrid Merx our group curated a performative lecture. On this webpage you will find weekly blog posts with interesting articles that relate to the overall planetary theme. Our mission and vision provide insight into what we hope to achieve with this project. The curatorial statement underlines why it might be helpful to gain a planetary perspective. Every team member wrote a Catalogue Text about an artwork that we found captures the planetary awareness. In the Theoretical Posts we dove into the theories and academic writings that can help better understand why the planetary perspective is necessary in the modern world. A preview of the performative lecture took place on the 10th of January 2019.

We kindly invite you to explore this webpage and with it the planetary perspective.

Yours truly, Fiep Nijhof, Janne de Kock, Claire van der Mee, Amy Gowen, Nicole Horgan, Merel Overgaag and Sarah Houterman

Contact information:

0 notes

Text

Mass Extinction

https://michaelwang.info/The-Drowned-World

In the history of Earth there have already been five mass extinctions (that we know of) and the sixth mass extinction is believed to currently be taking place. Mass extinction is an unfathomable concept to grasp for our human-centered minds. Those who acquiesce to the era of the Anthropocene understand that the human-species has an effect on the planet, but to what means can one define the age we live in when the Earth could annihilate everything that humans have subjected to meaning?

The artist Michael Wang’s The Drowned World reminds us of the unfathomable. With his outdoor plant installation he takes us back to the carboniferous period. With the end of the Permian age, over 251 million years ago, came the greatest mass extinction known to us. Due to a multitude of natural catastrophes whereby greenhouse gases were blasted into the atmosphere, Earth became inhabitable for 96% of the existing species. In Palermo, Italy, during the Manifesta 12 biennial in 2018, one could come across the descendents of these ancient plants, sprouting up from the ruins of an old gasworks. The remains of the plants that were exterminated during “the great dying” became the sedimentary layers of coal burnt in gasworks such as the one in Palermo. The burning of this coal rereleases the gases that were once in the atmosphere during the carboniferous period. The artificial placement of these plants alongside manmade industry entwines the human narrative with the earth’s primal history.

A mass extinction goes beyond simply the extermination of the human species. It encompasses the end of most life, ranging from the tiniest of organisms to the largest of mammals. Yet this thinking is in contradiction to the acceptance of antropogenic degradation. How can we as a species have an impact on a planet whose nature has eminent impact over all? How can the offspring of organisms dating from a pre-human age live alongside the systems that are concurrently dominating their possibilities of future life?

These questions are sparked when strolling amongst the fossils and flora of Wang’s artwork. As we continue to encourage each other that we have inflicted disastrous change onto our planet, thus we have the power to undo the earth of these ‘negative’ developments, perhaps it is best that the concept of mass extinction is so difficult to grasp. With mass extinction ever looming in the horizon of our consciousness we would be stifled and incapable of creation or regeneration. To end this blog post on a (semi-)positive note, in the words of Giacomo Leopardi :

“Nothing lives that is worthy Thy agitation, and the earth deserves not a sigh. Our being is pain and boredom and the world is dirt - nothing more. Be calm.”

0 notes

Text

Becoming Planetary & Planetary Media

In what ways does the planetary become evident - wether as object, process or event? How is the planetary configured, rather than assumed and given?

As we approach our upcoming curatorial event, these apposite and provocative questions - posed by sociologist Jennifer Gabrys in the e-flux article ‘Becoming Planetary’ - echo the crux of our discussions. As we are facing deep-rooted climate, social and environmental crises, contemplating the planetary and how this perspective can be manifested is extremely relevant to us as curators. As our primary focus is to provide an awareness of the planetary, how exactly do we broach this and how can our curatorial practice enable this?

Gabrys proposes becoming planetary as a ‘way to consider how the planetary is not a uniform or fixed set of conditions, but rather signals conditions of difference, as well as collective responsibility and possibility with and through those differences’. For Gabrys, we should be striving the make being planetary ‘as praxis’. For us, this is expressed through the adoption of the planet-wary lens. Can we get our audience to undertake a cognitive shift with us and will this result in a permanent change in the way that they perceive and relate to the living planet?

Another compelling component of Gabrys’ text is the notion of the forest as a form of planetary media, in that they are the site of multi-species inhabitations, ‘protests and struggles for ways of being in the world’ and register the accumulations of the environment bestowed upon it by nature and human actions. Gabrys notes the forests ability to transform human-planetary relations as ‘it at once resists a universal and singular view, while also bringing into focus a multiplicity of subjects and inhabitations’.

Perhaps the most pressing question she poses for us in relation to the forest is, ‘how does this gaze from within planetary inhabitations generate multiple modes of praxis?’. What role does the category of human play and the category of forest play in this eco-system and this discussion?In what way can we ask our audience to inhabit these categories and the planet-wary lens in a non-superficial manner? How can we together, across these different categories, consider and challenge the inequalities and crises of the current system such as climate change? We are excited to contemplate the manner in which we can fully embrace and demonstrate this dialogue in our upcoming event.

0 notes

Text

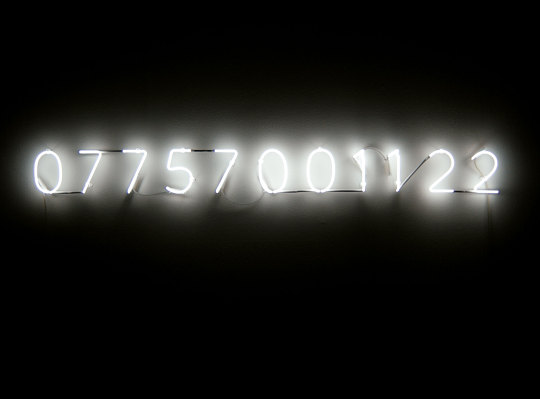

Katie Paterson, Vatnajökull (the sound of)

Katie Paterson’s installation artworks focus on human relationships and connections to both the Earth and the Planetary. She often takes recognisable objects such as pianos, disco balls and, in the case of Vatnajökull (the sound of), a telephone in order to articulate and reflect upon power relations, communications and connections between humans, nature and the planetary.

Image from http://katiepaterson.org/

In Vatnajökull (the sound of) a live phone line was created to an Icelandic glacier, via an underwater microphone submerged in Jökulsárlón lagoon, an outlet of Vatnajökull. The number 07757001122 could be called from any telephone in any country around the world, and the listener would hear the sound of the glacier melting.

Image from http://katiepaterson.org/

The idea was to articulate the devastating effects of the anthropocene and climate change in a more digestible, resonating and human level. So often these issues are seen as too big or too far beyond our reach as a human creating alienation and detachment on our part. Yet by encouraging real-time communication between the humans and nature it created a common language, a common story and a common understanding of how our actions as humans have such tragic implications.

Image from http://katiepaterson.org/

In relation to our exhibition, this work is poignant as it articulates the planetary from an everyday perspective. It encourages the open mindedness, the cognitive shift and the incorporation of multiple perspectives that we attempting as part of our project. Through her multidisciplinary practice, she manages to bring the vast scale and temporal dimensions of geological and cosmological events into sharp focus, creating art that focuses less on the human and more on planetary relationships.

For further information and resources: http://katiepaterson.org/

0 notes

Text

Plant Blindness, Plant Script, Plant Co-Authorship and Interspecies Dialogue

The neglect and dismissal of flora is not only limited to scientific outlooks but extends also to social and cultural domains with planets often being reduced to just aesthetic purposes. Alarmed by the relegation of threatened floristic communities to reductionist discourse, biologists have popularised the idea of plant blindness to describe an inclination “among humans to neither notice nor value plants in the environment” (Balding and Williams 1192). As a tendency to overlook flora, to underestimate its global ecological significance, or to reduce it to an appropriable resource, plant blindness could reflect the physiological constraints of the human processing of visual information. The pervasiveness of plant blindness and the inability to recognise vegetal lives and their complexities could be one of many factors contributing to the exponential species loss and biocultural disintegration that ever more characterises the Anthropocene.

Ways in which artists have attempted to connect plants and humans once again is through plant poetry and plant literature, a technique and form that incorporates layered, planetary narratives and discourse to not only highlight the wonders of plant life, but to create an interspecies dialogue.

Research into botanical percipience can be traced back at least to Charles Darwin and Jagadish Chandra Bose. Darwin and Bose were the first to imagine and develop novel instruments to make visible the endemic semiosis of vegetal life, or what they came to term plant script. Plant script incorporated modes of interspecies dialogue between humans and plants and made visible the non-linguistic forms of communication of plants, plant-script or plant-autographs. Although forgotten for a long time, this form of collaboration and communication has opened a world of potential for creative arts to engage, evoke and elicit plant sensitivities. Rather than constructing them as objects of representation, it entails the possibility of creative exchange between plants and humans in which plant script intergrades with the production of a text. The potentials of writing practices can therefore initiate new social, biological, political and imaginative perspectives on flora. Human-plant communication can be posited as a basis for interspecies collaboration in which botanical life is an agent, participant within, and contributor to the compositional process.

Rather than passive constituents of the landscape, plants exhibit a range of self-determined behaviours, including learning, remembering, solving problems, making decisions based on prior experiences, interpreting sensory feedback in order to negotiate environments, assimilating information to enhance survival and fitness, and, even, enacting forms of altruism including care.

The plant as co-author has been seen through multiples cases of literature, including eco-fiction, speculative fiction and perhaps most effectively, plant poetry. Examples include Wright’s Five Senses (1963), Murray’s Translations from the Natural World (1992), Easter Sunday (1993) and most recently, Power’s The Overstory (2018).

Plant fiction, plant poetry and the co-authorship between plants and humans is an integral part to our project as rather than speculative reverie, pathetic fallacy or barefaced metaphorisation, plant script becomes available to us through practices of listening to, looking at, feeling, tasting, smelling and walking in plant habitats. The interspecies dialogue requires a deeper understanding between fauna and flora, a reconfiguring of our relations on this planet and to one another and a cognitive shift in perspective towards the planetary.

For further information and resources: http://www.transformationsjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Trans30_08_ryan.pdf

#plantscript interspeciesdialogue planetarydiscourse planetaryperspective weeklyblogpost#weeklyblogpost

0 notes

Video

tumblr

Studio Roosegaarde

Space waste is a growing problem many humans are ignorant about because it is not a visual tangible problem. NASA calculated that there are over 21 thousand objects circling the earth. This space debris is non-functional, human-made materials is orbit. This band of levitating space junk skirts the Earth and jeopardises current space travellers and future missions. This is a serious problem because these particles travel at hyper velocities and if they collide with an incoming or outgoing space mission, serious damage could be done. This space junk has been piling up over the last 50 years. More than 60% of the debris can be attributed to two events. In 2007, China blew up a weather satellite which accounts for 900-pieces of debris. In 2009 a private satellite and Russian military spacecraft collided and left a trail of two thousand pieces.[1] An artist that started a project to make space waste visible from earth is Studio Roosegaarde in cooperation with ESA (European Space Agency). The project consists of two phases. First the performance of tracking the space waste via specially designed software. The surrounding area is darkened by shutting down all street and commercial lights. Green beams follow the space waste while its orbiting in Earth. Phase two is a multi year program that will capture space waste and up-cycle it into sustainable products. Phase one is currently housed at Kunstlinie in Almere. Daan Roosegaarde said the following about the project; “We need to look at space in a better way. What is space waste, how can we fix it, and what is its potential? Space is the smog of our universe.”[2] Studio Roosegaarde also uses art in order to ask attention for rising sea levels and the importance of water innovation. Waterlicht is a combination of LEDs and lenses which create an ever changing layer of light, influenced by wind and rain.[3] The feeling of being under water is strengthened through the use of fog. The fog moves through the LED light and becomes a layer of waves above the visitor’s head. The installation is accompanied by a live radio stream on which the artists explains his work and people share their stories about water related innovations and overcoming water related problems. The aim of the installation is to make people aware of the importance of innovation. However, the work can also be interpreted as a means to make people more aware of the consequences that climate change can have on their everyday surroundings. By making the ramifications of rising sea levels visible, the installation gives us insight into our future if we don’t change our perspective on environmental issues.

[1] JPL.NASA.GOV. (n.d.). JPL | Waste In Space. Retrieved from https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/infographics/infographic.view.php?id=10929 [2] Space Waste Lab | Studio Roosegaarde. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.studioroosegaarde.net/project/space-waste-lab [3] Waterlicht | Studio Roosegaarde. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.studioroosegaarde.net/project/waterlicht

0 notes

Video

tumblr

“Luminal” as a planetary lens

By Sarah Houterman (6244505)

Mathijs Munnik was inspired by the “Ganzfeld chamber” and its ability to change museum visitors perspective and way they view the Earth. The “Ganzfeld chamber” and “Luminar” both strive to change the viewers perception of himself and the way they relate to the planet. This notion of changing to a planetary perspective is also what our curatorial event focusses on. We want our audience to become more aligned with the planet and this installation could help achieve this mission. Munnik is a 28-year-old Dutch artist born in Leeuwarden, Friesland. He studied at the Minerva art academy in Groningen and the art academy of the Hague. He was nominated for multiple awards for his installation work and did a residency at the prestigious Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten in Amsterdam in 2015.[1] Munnik specialises in light installations but also in media and performance arts.[2] In his work the elements of light and sound play an important role. His immersive audio-visual installations allow for the spectator to get carried away into a world of Munnik’s making.[3] He creates sensory experiences of phenomena that normally are beyond our perception. With the Art & Space initiative Munnik strives to promote collaborations between artists and scientists that specialise in outer-space. For this he works with the ESTEC (European Space Research and Technology center) in Noordwijk, The Netherlands. Munnik strives to broaden his knowledge about electronics, astronomy and fluid dynamics. In terms of theory he wants to gain a better understanding of cybernetics.[4] The installation named “Luminal” was created in 2016 and was on display at the Fries museum in Leeuwarden in the exhibition “Phantom Limb”.[5] For this installation Munnik was inspired by the psychedelic effects of light and sound with which was experimented in the 1960s and 70s. Munnik sought to create a similar experience as the Ganzfeld chamber. This chamber was created in 1968 by artists Robert Irwin and James Turrell for NASA. After visiting this room people saw the real world with new eyes as if they were astronauts returning to Earth.[6] To recreate this effect Munnik developed his own lighting and colour system in a space without corners. The installation consists of a sound and light show inside a white cylindrical space. The cylinder was handcrafted and tailored to the specific space.[7] By climbing up three stairs the visitor walks on to a small wooden platform. The rainbow lights switch through an array of different shades accompanied by a high pitched sound. Due to the shape of the room in combination with the sound and lights it feels infinite. This feeling is intensified by the fact that only two visitors are allowed on the platform at the same time. When standing in the middle of the platform the visitor’s eyes are constantly adjusting to the changing light. The eyes are also seeking for a point to fix upon but fail due to the construction of the space. The ears are stimulated with a high-pitched sound, without words or rhythm. The combination of these three elements allows for a surreal and almost psychedelic experience. This foreign and slightly unsettling feeling stays with you for a period of time after you’ve left the chamber. It allows for you to look at the world through this “Luminal” lens.[8] “Luminal” is an example of how artists strive to change people’s perception and show them alternative ways of viewing the world. Much like the planetary lens adopting multiple perspective is key in understanding contemporary problems and can serve as a way to find solutions to issues we struggle with. The “Ganzfeld chamber” was an experiment that originated in the science sphere and crossed over into the arts. The “Ganzfeld Chamber” created by the Californian Light and Space movement, was conceptualised as a way to make visitors aware of their own visual experience One of the creators, James Turell, became an influential sound and light artist. With his work he strives to make light tangible.[9] In a way Munniks work does this as well, bringing about a change in perspective through the means of awareness. When we are aware of something it is easier to act upon it. Thus making a meaningful change is our viewpoint.

Footnotes:

[1] "Matthijs Munnik () | Resident." Rijksakademie Van Beeldende Kunsten. Accessed December 17, 2018. https://www.rijksakademie.nl/ENG/resident/matthijs-munnik/about. [2] "Matthijs Munnik - Stroom Den Haag." Www.haagsekunstenaars.nl. Accessed December 17, 2018. https://www.haagsekunstenaars.nl/cv/76013/Matthijs+Munnik. [3] DordtYart. "Matthijs Munnik." Centrum Voor Hedendaagse Kunst. Accessed December 17, 2018. http://dordtyart.nl/archief/sense_of_sound/matthijs_munnik. [4] "Matthijs Munnik." Stimuleringsfonds Creatieve Industrie. Accessed December 17, 2018. https://stimuleringsfonds.nl/nl/talentontwikkeling/matthijs_munnik/. [5] Winter, Agnes. "Sollen Met De Werkelijkheid - Phantom Limb in Het Fries Museum - Reviews." Metropolis M. Last modified August 5, 2018. https://www.metropolism.com/nl/reviews/35925_phantom_limb_fries_museum. [6] Exhibitiontext at ‘Phantom Limb’ in Fries museum. Leeuwarden. Consulted 15 December 2018. [7] "Stucwerk Voor Kunstwerk 'Luminal in Fries Museum." Jorritsma Bouw. Last modified February 8, 2018. https://www.jorritsmabouw.nl/stucwerk-kunstwerk-oneindigheid-fries-museum/. [8] S. Houterman, visiting “Phantom Limb” in the Fries museum, Leeuwarden, 15 December 2018. [9] "James Turrell." Kunstbus. Accessed January 22, 2019. https://www.kunstbus.nl/kunst/james+turrell.html.

0 notes

Text

The System of Stability (2016)

Sasha Litvintseva in collaboration with Isabel Mallet

Film / 17 min / 2016

Trailers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URodDlzjM1Q&t=3s & https://vimeo.com/168080539

By Amy Gowen

The System of Stability by Sasha Litvintseva, 2016

Artist, researcher, and curator Sasha Litvintseva’s uses film, lecture and text to explore the theory of geological filmmaking. Such filmmaking contemplates the uncertain thresholds of human/nonhuman, inside/outside and visible/invisible through the intersections of media, ecology, history and science, in an attempt to challenge typical human-centric narratives. Through its geological filmmaking form of “experimentation, imaginative invention, and radical thinking,”[1] The System of Stability initiates creative, perceptual and philosophical shifts in cognition that offer new ways of comprehending ourselves and our relation to the world.

Sasha’s project of Geological Filmmaking includes a larger body of works that each focus on the relationship between humans, non-humans and their direct environments. Through this she engages with the limits of current Anthropocentric narratives by entangling human voice and agency with other geological matter including the likes of volcanic rock faces, desert sinkholes and molecules of poisonous Asbestos in the atmosphere, with a view of engaging with the in/visible power structures at play between humans and non-humans.

The System of Stability by Sasha Litvintseva, 2016

The System of Stability in particular acts as an encounter with the landscape on its own terms, where the inorganic takes the narrative lead, commanding the attention of the viewer. The film is divided into three parts, the opening animation and voiceover is of a mathematical point, a single white dot against a black background. The point narrates itself through a monologue that describes its transition from nothingness to existence, inviting its audience to contemplate the lives of matter we typically assume to have little or no agency. The middle section builds on this notion and is composed of mostly static frames of the rocky terrain of the volcanic island of Lanzarote, accompanied by an intrusive and jarring score that reflects the power and omnipresence of the landscapes on screen. Finally a closing scene of the landscape in motion is accompanied by a new narrator, one that is positioned clearly from a human perspective - we see the landscape from a moving car as the camera “blinks” to mimic human sight. The landscape moves by at increasing speed as the human narration begins to contribute to the loss of subjectivity that the film evokes. After having lived on Earth for millions if not billions of years, the rocks we see on screen help narrate quite different stories about the world than the ones told by human beings, making it clear that it is not the human who exerts the dominant voice within this film, cuing us to consider that the living planet is not only for us.

Litvintseva takes inspiration from critic and filmmaker Jean Epstein who wrote in 1923 that “if we wish to understand how an animal, a plant or a stone can inspire respect, fear and horror - those three most sacred sentiments - I think we must watch them on the screen, living their mysterious, silent lives, alien to the human sensibility.”[2] In The System of Stability the camera eye is in essence non-human, unburdened by the knowledge and meaning of the objects it captures, therefore granting it the ability to represent other nonhuman agencies. Sasha states that through her geological filmmaking she is “trying to visually disrupt the hierarchies governing relations between subject and object, nature and culture – the dichotomies inherited from modernity that have not served us well.”[3] From this her theory of filmmaking can be understood as a visual strategy for the Anthropocene in order to think and feel on geologic scales and time frames that incorporate the other-than-human as much as the human, in doing so The Stability of the System probes into the vibrancy of matter and the creative agency of nonliving things.

The System of Stability by Sasha Litvintseva, 2016

This is a key work within Planetary Awareness for Earthlings in a Post-global Age as Sasha Litvintseva successfully challenges our current unconscious dependence upon globalist, anthropocentric perspectives and frameworks. Described as depicting a “quiet catastrophe,”[4] the film attempts to test preconceived attitudes through the (re)thinking of ideas such as natureculture, non-human agency and deep time to encourage an increased planetary vision of a world which portrays multiple perspectives, as well as illustrating an alternative frameworks that can acknowledge the ecosystem of the living planet. Through such a narrative reframing, we witness the entanglement of human and non-human agencies to produce a more nuanced, emphatic and layered perspective, aiding in our aim to (re)member, (re)shape and (re)join our relationship with the living planet. Moving away from the human-centric and towards the Planetary perspective.

References:

[1] "Sasha Litvintseva Texts." Sasha Litvintseva. Accessed December 21, 2018. https://www.sashalitvintseva.com/gftext.

[2] Transformations Journal – Transformations Journal of Media, Culture & Technology. Accessed December 21, 2018. http://www.transformationsjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Trans30_03_mulvogue.pdf.

[3] "Visual Strategy for the Anthropocene." INRUSSIA. Accessed December 21, 2018. http://inrussia.com/visual-strategy-for-the-anthropocene.

[4] Transformations Journal – Transformations Journal of Media, Culture & Technology. Accessed December 21, 2018. http://www.transformationsjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Trans30_03_mulvogue.pdf.

Bibliography & Further Reading:

-Transformations Issue 32 (2018), Geological Filmmaking: Seeing Geology Through Film and Film Through Geology, pp.107-124

-Transformations Issue 30 (2018), Catastrophe Aesthetics: the moving image and the mattering of the world, pp.40-55

-“Visual Strategy for the Anthropocene.” INRUSSIA. Accessed January 20, 2019. http://inrussia.com/visual-strategy-for-the-anthropocene.

- Screen and Audiovisual Research Unit. Accessed January 20, 2019 https://culturetechnologypolitics.files.wordpress.com/2018/03/sonic-acts-essay-compressed.pdf

0 notes

Text

D A R K M O U N T A I N: Issue 9

Merel Overgaag – 3997405

To be humble means to lay oneself low, but also to be grounded, to return to the solid and material.[1] Dark Mountain: Issue 9 – The Editors

The Dark Mountain Project is a collective of creative writers that has been on a planetary mission since 2009. The collective uses the medium of storytelling to challenge the meta-narratives of our societies, that they conceive as myths. They call them ‘the myth of progress, of human-centeredness and of the separation between human and nature’.[2] In this exhibition you find Dark Mountain: Issue 9, a book release from spring 2016 of the Dark Mountain Project. In no less than 300 pages, we are taken on a poetic, literary and intellectual journey into humbleness.

The term humble is derived from the Latin word humus, which means ‘earth’. Humbling then would be a process of grounding down; of realizing that the human self is not the sacred supreme being we ought ourselves to be. However, the artists do not point fingers nor scream of urgency. Instead, by taking on an open and explorative approach, they are on the horizon of raising planetary awareness. In this sense, both The Dark Mountain Project as well as this issue’s topic lie at the heart of our exhibition.

In the category of fictional storytelling, the book offers A Good Place by Kathrine Sowerby. This multi-species fairy tale-like story counts no more than six sentences, and feels like a reminiscences of forest life and human-animal relationships.[3] A writing by Andrea Hejlskov hints towards a certain melancholia that is sensible in our fast-changing societies. In The Loss of Function, Hejlskov speaks of several forms of extinction. Besides the extinction of wild life, our globalizing world also causes certain social roles to fade, such as that of the nomadic female storyteller and the advisory wise elder.[4] Hejlskov has personally chosen to embrace the planetary, by living in primitive wilderness since about eight years.[5]

More in essay-form is Over Yonder Horror by poet, editor and prison tutor Em Strang. Strang carefully explores the question of ‘what does it mean to bear witness to the suffering of others?’ In a search for meaning, she moves from arguments of activism and responsibility, onto Buddhist perspectives of deeply accepting the unchangeable things in our world. Strang concludes that the goal- and solution-oriented ways of responding that characterize Western culture are withholding her form understanding and emotionally processing the atrocities of today’s world.[6] This thought is close to the planetary approach, in that it implies abstraction from globalist frames of thought as a way to deal with global issues.

Furthermore, in Complexity and its Opposite – an adaption of his most recent book The Myth of Human Supremacy - Derrick Jensen offers a philosophical critique in the spirit of critical animal studies and posthumanism. Through empirical evidence and philosophical argumentation Jensen points out to the intelligence of nature. He emphasizes how supremacist thought and fear refrains humans from realizing nature’s intelligence and from developing language skills to communicate with multiple life forms.[7] In this light, Jensen’s work serves as a reminder that in order to raise planetary awareness through an artistic pursuit, participants must both be willing and able to become Planetwary in the first place.

Halfway throughout the book follow several evocative paintings from different artists. Kate Williamson’s intuitive painting Soft Rain relates to the more subtle power of nature, that influences humans in intangible ways.[8] Rebecca Clark’s All Will Be One plays with organic geometry, depicting states of transformation in the cycle of life and death of a leaf.[9] Andrew Phillips Blood of the Earth-series uses primary colors and the physicality of mountains to depict a ‘bloody earth’. The work hints towards the rich mysteries of both life creation and the inevitable processes of decay. As the red soil becomes ‘the record of everything which has failed to live forever, a physical embodiment of deep history,’ [10] Philip’s work reveals the planetary from a historical and evolutionary perspective.

Dark Mountain: Issue 9 acknowledges as no other the immense role of storytelling and narration in exploring the planetary. However, its ambition is not to enfold a universal true tale of our world. Rather, the artists hope to come up with stories that seem more honest and just responses to the increasing effects of climate change, alienation and mass extinction. Besides, the book serves as a reminder that integral to being Planetwary is to obtain an attitude of humbleness. Both the theme as well as the approach lead this publication to a central place in our exhibition. A place that is perhaps more prominent and outstanding than its humble makers might accept.

Footnotes

[1] Dougald Hine and Paul Kingsnorth, Dark Mountain: Issue 9 (Croydon: Dark Mountain Project 2016, 2016), 2.

[2] Dougald Hine and Paul Kingsnorth, "About the Dark Mountain Project," Dark Mountain, accessed December 21, 2018, https://dark-mountain.net.

[3] Hine and Kingsnorth, Dark Mountain, 43.

[4] Hine and Kingsnorth, Dark Mountain, 44-48.

[5] Andrea Hejlskov, "The Forest Life," Andrea Hejlskov, last modified August 21, 2018, https://andreahejlskov.com/the-forest-life/.

[6] Hine and Kingsnorth, Dark Mountain, 74-83.

[7] Hine and Kingsnorth, Dark Mountain, 90-101.

[8] Hine and Kingsnorth, Dark Mountain, 123.

[9] Hine and Kingsnorth, Dark Mountain, 122.

[10] Hine and Kingsnorth, Dark Mountain, 124-125.

Bibliography

Hejlskov, Andrea. "The Forest Life." Andrea Hejlskov. Last modified August 21, 2018. https://andreahejlskov.com/the-forest-life/.

Hine, Dougald, and Paul Kingsnorth. "About the Dark Mountain Project." Dark Mountain. Accessed December 21, 2018. https://dark-mountain.net.

Hine, Dougald, and Paul Kingsnorth. Dark Mountain: Issue 9. Croydon: Dark Mountain Project 2016, 2016.

0 notes

Text

Forest Law (2014)

Ursula Biemann & Paulo Tavares 2-channel video installation, maps, documents, objects, publication

Nicole Horgan

Forest Law (2014) is an exemplary illustration of the artist, researcher and video essayist Ursula Biemann’s pluralistic practice which examines and confronts planetary concerns such as asymmetries of wealth, unequal ecological exchange and climate change by interweaving experimental video, interview, text, photography, cartography and materials. For this particular piece Biemann collaborated with architect and urbanist Paulo Tavares, whose own practice deals with the visual and spatial politics of territorial conflicts and climate change in the Amazon and other frontiers across the third world. Through Forest Law’s two-channel video installation and accompanying documentation including publications, photographs, maps and wall texts, Biemann and Tavares broach the frontiers of the Ecuadorian rainforest to bring to light the work of indigenous lawyers and experts whose work in amending the country’s constitution led to the establishment of fundamental rights to natural eco-systems.

Where the Amazon floodplains meet the Andean mountains, the Ecuadorian rainforest is not only home to indigenous nations and great ethnocultural diversity but also one of the most biodiverse and resource-rich regions of our planet. It is also as a result under extreme pressure from large-scale mineral and oil extraction and exploitation, despite the region being considered the sovereign land of indigenous nations. Forest Law focuses on a series of landmark legal battles held in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights where claims were made for the rights of nature in the face of this thereat of human destruction. A pertinent case that is included within the piece was won by the Sarayaku people, whose legal argument centred on the centrality of the ‘living forest’ in their community’s cosmology, modes of being and ecological survival. For the Sarayaku people, nature is not a passive background against which our human political and economic disputes play out, but instead should be an active legal subject bearing rights of its own. Forest Law brings together various narrative voices to re-tell these cases through personal testimonies and by mapping the historical, political and ecological dimensions of the trials. By doing so, the Forest Law enters into a conversation concerning the entanglements between a plethora of pertinent issues and conflicts such as environmentalism, post-colonialism, social justice, and of the human and the post-human.

Biemann and Tavares’ theoretical intervention narrates a changing planetary reality while figuring and reconfiguring human-planetary relations. Throughout Forest Law, Biemann and Tavares refer to Michel Serres’ text Natural Contract in which he proposes that humans should adhere to a contract with the Earth and its other inhabitants ‘in restitution for and recognition of climate change’. Echoing Donna Harraway’s multi-species concept, the interlocutors within Forest Law imbue this ‘natural contract’ by espousing a move away from an anthropocentric point of view towards a geocentric one in which an approach of radical connectedness serves to deconstruct the hegemonic notion of the human and promotes a unique model of equality. Further to this, in Jennifer Gabrys’ compelling text Becoming Planetary she posits the forest as a form of planetary media on account of it acting as a proxy that records and registers the effects of climate change. For Gabrys, the forest has the potential to enact a crucial role in transforming human-planetary relations as ‘it at once resists a universal and singular view, while also bringing into focus a multiplicity of subjects and inhabitations’. This notion of the forest as a site through which planetary inhabitations are manifested is particularly powerful when one considers the rendering of the forest as a physical, legal and cosmological entity in the cases represented in Forest Law.

Crucially, Forest Law urges us to reconsider our position in the world and of being with the planet. One could argue that the Sarayaku and other narrators featured within Forest Law embody the planet-wary; their planetary perspective is manifest through a greater capacity for empathy and response-ability for our living planet and has resulted in a direct and active confrontation of the dominate globalist and problematic political frameworks.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Getting Down and Dirty with Mother Earth: naturalization through ecosexuality

By Claire van der Mee

“WE ARE THE ECOSEXUALS.

The Earth is our lover. We are madly, passionately, and fiercely in love, and we are grateful for this relationship each and every day. In order to create a more mutual and sustainable relationship with the Earth, we collaborate with nature. We treat the Earth with kindness, respect and affection”. [1]

Dirt Bed is the title of a performance that took place in 2012 in Grace Exhibition Space in New York. Artistic collaborators and lovers, Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens, explore the ways sexology and ecology intersect through performance art and visual installations. The two artists were participants during Documenta 2017 where they contributed multiple works, including cuddling performances in bed, public actions on the streets of Athens, and an Ecosex walking tour in Kassel. Stephens and Sprinkle not only figuratively embrace the planetary, they literally embrace the planet-(ary) with outstretched arms and open legs by participating in acts of love with the elements of the Earth. They have even gone so far as to marry these elements. Over the course of seven years, Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens have pledged their love to the Appalachian Mountains, the sea in Venice, the coal in Spain, Lake Kallavesi in Finland, the moon, and the sun through their public wedding rituals.[2]Their artistic displays of public affection, which reach beyond the human body and seep into the components that constitute our planet, transform our attitudes towards the things around us. How deep is our love if it can plummet beyond the human into the darkest crevices of a lake or when the sky truly is the limit? How are movements such as ecosexuality and ecoqueerness changing the way we perceive our planet?

Through these performative acts, this artistic duo leads the participant-observer into a meta-narrative. “Sprinkle and Stephens’s ecosex workshops and actions are laboratories for the transformation of subjectivity.”[3] Within the frameworks of art one accepts the coyness of the project and may take on the role that is presented to them; the free spirited lover whose love knows no boundaries. Sprinkle’s and Stephens’ esthetics are camp and they are queer in their sexual orientation as well as in the definition of the word, in a non-conventional sense. Due to these playful expressions the members of the audience approach the act as a spectacle, a glittery festivity that invites them to step into a comedy about radical love-expression. Yet it this radical ‘pretending’ that dislocates us from our initial notion of the elements around us. The audience is seduced into a new perspective and relationship with the natural.

This transition into ‘the natural’ is of an intersectional nature. As you explore the sexual urges within your body and learn to extend them beyond the gender binaries, you also learn to reach beyond the binary of affinity between two human bodies. Eco-queerness criticizes the ‘naturalness’ assigned to peoples’ genders and sexuality[4]and as a reaction the movement queers nature. The ‘natural order of things’ is re-ordered through Sprinkle’s and Stephens’ radical acts as the audience is encouraged to ‘come to their senses’ by invoking sensuality and focusing on sensitization. As Joshua Sbicca writes:

“By taking a more fluid and spatial approach to understanding the makeup of the eco-queer movement, I have found that ideas, symbols, and discourse matter as much as the materiality of space.” [5] In Dirt Bed different ingredients compose the sexual or loving act: the earth (the dirt), the bed, the people lying in the bed and covered in earth, the voyeurs in the room, the room itself and the objects contributing to the atmosphere (for example the candles) are all presenting this deed.

Sprinkle and Stephens lure the audience into a reality where the relationships between people and Earth are not bound by human-centric scripts. While we as curators encourage you to “undertake a cognitive shift with us, to test and perhaps jump into the water”[6]this collaborative-duo actually jumps into the water in an act of collectively raising our planetary awareness. Their gestures are bold, yet tender: intertwining language and matter, spreading human rights onto the non-human, guiding us in our relation towards nature through ethos and subjectivity. Ecosexuality and eco-queerness are provocative and arouse sensitivity in our thinking about earthly elements. Sprinkle’s and Stephens’ movements allow us to step over the threshold of binaries, of the human/non-human, male/female, subject/object, nature/culture, and help us to grasp that our interactions are constituent elements of that what we call planet Earth.

[1]From the home page of Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens website: http://sexecology.org/

[2]http://sexecology.org/ecosex-weddings/

[3]Preciado, Paul B. “Documenta 14: Daybook” 2017. https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13487/annie-sprinkle-and-beth-stephens

[4]To read more about ‘naturalness’ being attributed to gender and sexuality read: Butler, J. “Undoing gender”. 2012. New York, NY: Routledge.

[5]Sbicca, Joshua. “Eco-queer movement(s) Challenging heteronormative space through (re)imagining nature and food” 2012. University of Florida, USA

[6]https://thinkingartsandsocieyii.tumblr.com/tagged/curatorialvision

0 notes

Text

The Dark Mountain Manifesto

Catalogue Text by Janne de Kock After both quitting their jobs as esteemed journalists, Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine decided to join forces and create a platform on which new (and different, and better) stories could be invented. Having both a history as serious environmental activists, they foresaw that in order to come close to a possibility of solving environmental issues, it was crucial and instrumental to first clearly see the kind of thinking and acting that created these issues. They resigned from their activists’ activities, and put their focus on the disentangling of our civilization’s stories. The result of their initial findings is presented in Uncivilization: The Dark Mountain Manifesto.

The publishing of the Dark Mountain Manifesto in 2009 counted as the official start of the Dark Mountain Project. Where most artistic manifestos imply the notion of a dogmatic standpoint, the Dark Mountain Project uses it as their starting point towards further development. The manifesto ultimately stools upon eight principles, but if there is any dogma contained within, it is the questioning of the stories our culture is telling itself. The authors have named this ongoing process of questioning uncivilisation: a twofold enterprise where artists raze the beliefs upon which our civilization is built to the ground, and create new stories from the soil of this cultural debris.

The manifesto is a first example of this uncivilisation. It puts forward several myths on which contemporary (Western) society is built, of which the most important one is the denial of the existence of myths. The authors define a myth not as a lie, or as a fiction, but as a founding narrative: a myth is a way in which we look at the world. Humans have become to believe in the myth of science, where the outcome of scientific research is regarded as ‘the truth’. The authors are not denying the relevance of science, they are simply emphasizing its functioning as a founding narrative.

Uncivilisation and the Planet-wary The motif of a dark mountain symbolizes ‘the great, immovable, inhuman heights which were here before us and will be here after.’[1] By learning the prevailing human myths, and consciously unlearning them (i.e. by uncivilizing), we will re-realize our unconditional connection with planet Earth. In other words: we will become Planet-wary. By uncivilizing, we will reach these ‘dark mountains’ and ‘from their slopes we shall look back upon the pinprick lights of the distant cities and gain perspective on who we are and what we have become.’[2] As we loosen our grip on the frame of civilization, we become more and more rooted into the soil of Earth: uncivilisation and the Planet-wary go hand in hand.

As the first of the eight principles which bring the manifesto to a close, goes:‘We live in a time of social, economic and ecological unravelling. All around us are signs that our whole way of living is already passing into history. We will face this reality honestly and learn how to live with it.’[3] The Mountaineers don’t want to ‘solve’ our ecological crises if it means we try to come up with more sustainable sources of natural power to use for the enhancement of the human species. They are not trying to blame anybody (but acknowledge that everybody is to blame) for causing current environmental crises. Instead, they accept the consequences of the anthropocene, and root for a new way of living on (not working with) planet Earth as it is today.

The curation of the Planet-wary centres around the art of invitation and its resulting encounters.[4] The Dark Mountain Project is one of the art projects that develops an (un)learning process - as it unfolds. It focuses on the art of reframing and acknowledges the absolute necessity of a new language. The manifesto in that sense counts as an example of an exercise in unlearning (or uncivilizing, as the authors would say). Because it emphasizes the importance of new communications, and because the original object that goes as the manifesto is the text (not the print), it will not be conventionally displayed as a book. Instead, visiting the Dark Mountain Exhibition is an immersive experience where the visitor finds himself dwelling in Augmented Reality unspoiled natural landscapes, where the principles of the Dark Mountain Manifesto will present themselves in literal (as the displayment of text) and metaphorical form. The latter implies that the visitor is challenged to discern the myths of the exhibition space and encouraged to perform the uncivilisation.

Under intellectual guidance of Kingsnorth and Hine, the Dark Mountain Project developed into a network of artists, writers, poets and thinkers. Since the publication of the manifesto in 2009, they have published periodicals in which its contributors (‘Mountaineers,’ as they are called) keep uncivilising via essays, artistic images and poetry.

References [1] Kingsnorth and Higins, “Dark Mountain Manifesto,” 14. [2] Ibidem. [3] Kingsnorth and Higins, 15. [4] See also our Curatorial Vision & Mission Statement: https://thinkingartsandsocieyii.tumblr.com/tagged/curatorialvision .

0 notes

Text

CITY ASTRONAUT – Marjolijn van Heemstra

Fiep Nijhof (5551315)

“If we want to save our planet we have to live like astronauts, said astronaut Wubbo Ockels on his deathbed.” This quote is from the introduction text of Marjolijn van Heemstra’s new performance City Astronaut (Stadsastronaut). “Astronauts say we need to zoom out. Seeing what we are and what we have to lose gives us the perspective that we currently lack.” Marjolijn van Heemstra describes herself as a “writer, poet, theatre maker, columnist, sometimes journalist but preferably a combination of all that,” and she also says she is a fan of astronauts.[1] Most of her performances are described as documentary theatre, as van Heemstra often makes the theatre a stage for her research. Her latest work confirms this: in 2017, van Heemstra made a performance where she analyses the Dutch children’s book Crusade in Jeans by Thea Beckman. In that same year, she made the performance Zohre, where she discusses Dutch refugee issues together with Zohre, her Afghan friend.

The performance City Astronautcan be seen as a report about an astronaut training program van Heemstra developed for earth residents. She created a lifestyle in which earth residents live like astronauts and tested this with neighbors in an old neighborhood in Amsterdam. VanHeemstra made the performance City Astronautto explain how concerned she is about our future world. During the performance, her idea is to “find a manual for the future”together with space-specialists, futurologists and science fiction.[2] Because of light pollution we are unable to see the universe and the stars as we used to see it a few decades ago. She explains in a Dutch journal that her search to this manual for the future is a reaction to this view we lost of the universe. [3] In an interview with Annemiek Schrijver for the Dutch TV show De Verwondering, Marjolijn van Heemstra explains she wants people to look from an astronaut’s perspective in order to save the earth. She says: “there are already a lot of people attempting to save the world by living differently. An astronaut’s perspective could help with that. We should zoom out, see the planet and understand what that is.” City Astronaut explores this perspective.

Inspiration

In the De Verwondering, van Heemstra also explains that, in order to reach the astronaut’s perspective, “you must be willing to lose your own perspective.” Van Heemstra finds inspiration in a letter written by president Jimmy Carter in 1977.[4] Carter suggests life on other “inhabited planets and spacefaring civilizations.”[5] He addresses his letter to species we have not yet met, writing: “we hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations.”[6] Van Heemstra explains this letter was sent into space together with recordings of “hello” in two hundred different languages and with pictures of human civilization (a little girl eating an ice cream for example). She admires the way Carter looks at the planetary; losing his own perspective in order to see a possibility of life outside of our own world. This letter literally moves beyond the global – to look for life in the planetary.

Other work

In addition to De Verwondering, Marjolijn van Heemstra made other work that reveal her interest in other perspectives to look at the world. In her podcast Sør, she talks about the times she went to secondary school in Rotterdam. The podcast discusses how her history teacher Ronald Sørensen inspired her at the time. She illustrates this on the basis of a specific memory where Sørensen says to his pupils: “if you always only look out of this specific window in this classroom, you will never see the entire reality. If you really want to know what our reality is like, you have to change your position regularly.”[7] Van Heemstra explains she sees this statement as a way to look at life; a way to relate to the other and a way to look at our future world.

Van Heemstra also developed a project in Rotterdam, called RASA – the Rotterdam Academy for City Astronauts. This is an initiative of van Heemstra with Christiaan Fruneaux and Edwin Gardner from Monnik, an organization that “assists storytellers and innovators with speculative worldbuilding.”[8] The RASA academy's guideline is the overview effectthat occurs at a large number of astronauts who look at the Earth from space. Many of them experience an overwhelming sense of connection with and responsibility for our earth.[9] RASA organizes events for and about astronauts, such as lectures and performances in the city of Rotterdam.

[1]Marjolijn van Heemstra is schrijver en theatermaker. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.marjolijnvanheemstra.nl

[2]Stadsastronaut - Marjolijn van Heemstra

[3]Marjolijn van Heemstra. Zonder uitzicht op het heelal is de mens opgesloten in een zelfgemaakte wereld. | Trouw. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.trouw.nl/samenleving/zonder-uitzicht-op-het-heelal-is-de-mens-opgesloten-in-een-zelfgemaakte-wereld~abcef8d8/?fbclid=IwAR2pAzxrXJtCPAE72Gcpgakp1rau-6POzjjZ8HUJI2LkNE2ZJfqI1EomvVE

[4]Voyager Spacecraft Statement by president Jimmy Carter, 29 juli 1977

[5]Marjolijn van Heemstra - De Verwondering [Video file]. (2018, October 21). Retrieved from https://www.kro-ncrv.nl/deverwondering/seizoenen/seizoen-2018/marjolijn-van-heemstra

[6]Ibidem

[7]Sør. Deel I [Podcast] (2018, August 3). Retrieved from https://www.sordepodcast.nl/afleveringen/2018/7/31/deel-i

[8]About Monnik – Monnik. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.monnik.org/about/?lang=en

[9]Toekomstlab #4 | Overzichtseffect | BrabantKennis. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.brabantkennis.nl/activiteit/toekomstlab-4-overzichtseffect-1

0 notes

Text

THE PLANETARY COMMONS

By Nicole Horgan

By aligning the concepts of the planetary and the commons, curator Nicola Triscott offers a distinctive rejoinder to the dominant interpretive framework of the Anthropocene and it’s oft criticised limited direction and political agency in addressing this irrefutable age of ecological crisis.[1]In order to fully discern the potentially of the entangled concept of the planetary commons in the face of this crisis and its relevance to our exhibition, it is beneficial to dissect and assess these initial concepts and their interconnections as well as the hybrid planetary commons concept’s position within the wider ‘planetary turn’ in contemporary criticism and theory.[2]

The planetary was originally developed by Postcolonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak to name an ethical alternative to globalisation, seeking not to ‘generate an evasive figure, but rather…to [present] an inexhaustible diversity of epistemes’ which would enable us to think differently about being human and becoming collective.[3]The all-encompassing lens of the planetary enables us to ‘transcend the uniquely human concerns of the global’ and this is particularly relevant in relation to the current ecological crisis. In relation to this, artist Jennie Gabrys posits the planetary as a distinctly ecological concept that is ‘more of an indeterminate condition and set of relations that sparks new encounters with collective inhabitations that do not turn into…the usual designations of environmentalism’.[4]Concurrently, Elias and Moraru of The Planetary Turn also suggest that the planetary refocuses our attention from the regulative principles of the globe, with their ‘uncomfortable associations with paternalism, colonialism, and monopoly capital’, to the ‘stewardship’ of the planet and ecocritically informed discourse.[5]

With this notion of stewardship in mind, it is particularly compelling to unite the planetary with the concept of the commons. The commons is defined as a shared resource in which all stakeholders have an equal interest and it intrinsically offers a more equitable, environmentally aware and intrinsically holistic view of society.[6]The global commons - of which planetary commons is an elaboration of - applies this idea of the commons to international, supranational or global domains in which common-pool resources are found. International law identifies four global commons: the high seas, the atmosphere, Antarctica, and outer space.[7]Triscott’s use of the term planetary commons denotes within it the natural resources of the planet, common-pool resources previously stated as well as the spaces within which these resources are found.[8]This incorporation of the commons brings into question our capacity for response, based on a shared sense of responsibility in which we are all equally held accountable for our actions and their impact on our society and planet. Moreover, the planetary aspect acknowledges that the designation of the term commoner can also be applicable to a wider network of ‘actants’, not only including humans but also non-human animals, plant life, microorganisms, technology, geology, ecosystems, atmosphere.[9]What makes the planetary commons so pertinent is its emphasis on an expanded and collective sense of ecological, social and affective responsibility and reciprocality in the face of these increasing ecological concerns.

It is incredibly valuable to our work as ‘planet-wary’ curators to understand the planetary commons beyond its definition as a concept and as an interpretive framework and curatorial model. This importance can be justified by virtue of its commitment to reciprocity, its interdisciplinary potential to produce knowledge concerning contemporary environmental and social issues and its potential implications outside of the art space. As the images and ideas that we consume are important for feeding the collective social imaginary of the planet, it is of great consequence to embrace the planetary commons as a curatorial strategy so that a greater repertoire of images, texts, and actions relating to ecology, technology and politics can ultimately have an impact on shaping this imaginary, showing how we can no longer be passive in our attitudes and instead suggesting directions for collective environmental and political action.

REFERENCES

[1]Nicola Triscott, ‘Curating contemporary art in the framework of the planetary commons’, The Polar Journal, 7:2, 2017

[2]Amy J. Elias, Christian Moraru, The Planetary Turn: Relationalility and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty-First Century, Northwestern University Press, 2015

[3]Jennie Gabrys, ‘Becoming Planetary’, Accumulation, e-flux, 2 October 2018

[4]ibid

[5]A. J. Elias & C. Moraru, The Planetary Turn,xxiii

[6]A. J. Elias, ‘The Commons . . . and Digital Planetarity’, The Planetary Turn: Relationalility and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty-First Century, Northwestern University Press, 2015, 37

[7]Triscott, Curating contemporary art…, 375

[8]ibid

[9]ibid

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amy J. Elias, Christian Moraru, The Planetary Turn: Relationalility and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty-First Century, Northwestern University Press, 2015

Jennie Gabrys, ‘Becoming Planetary’, Accumulation, e-flux, 2 October 2018

Nicola Triscott, ‘Curating contemporary art in the framework of the planetary commons’, The Polar Journal, 7:2, 2017, 374-390

FURTHER READING

Buck, Susan J. The Global Commons: An Introduction. Washington, DC: Island, 1998.

Demos, T.J. Against the Anthropocene, Visual Culture and Environment Today. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017.

Elias, Amy J. “Art and the Commons.” ASAP/Journal 1, no. 1 (2016): 3–15.

Roberts, John. “Art, Neoliberalism and the Fate of the Commons.” Academia.edu (2015). https://www.academia.edu/25319592/Art_Neoliberalism_and_the_Fate_of_the_Commons1

0 notes

Text

Planetary Storytangling

By Amy Gowen

“It matters what stories we use to tell other stories with…it matters what stories make worlds and what worlds make stories.”[1] (Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble)

As long as there have been humans on this living planet, storytelling in all its forms has existed as a way of imagining, disseminating and producing information, which, in turn, has successfully aided in creating our perceptions of the world picture. Brian Boyd has argued that storytelling serves evolutionary purposes, as life itself is made of stories through which meanings are differentially enacted, and over thousands of years, humans have transformed their experiences, hopes, and fears into such storytelling.[2] Given this, it is important now, more than ever, to investigate the ways in which we currently tell stories about global environmental change.

The mediums of visual, written and sonic storytelling have been consistently used to frame and investigate the Anthropocene, yet humans still suffer from reductionist viewpoints of homo-centrism and a “crisis of imagination.”[3] Donna Haraway acknowledges this crisis and emphasizes the importance of intertwined worldings of Natures, cultures, subjects and objects. This implies that as crucial as storytelling is to understanding our planet and existence in this world, it also runs the risk of relentless contingency if limited to purely human-centric narratives.[4] In agreement with Haraway’s emphasis on intertwined worldings, William Connolly believes that the preciousness of classical humanism must be challenged through entangled humanism, adopting a “we” instead of “I” stance that includes humans, non-humans, organic and non-organic matters in the stories we tell.[5]

In terms of curating, the detailed mapping of story/ies that are played out within exhibition planning, alongside the collection of relevant artefacts to present, illustrate particular and specific stories. This said, using our current forms of storytelling as a curatorial approach runs the risk of neglecting narratives that can aid in evolving our perspective of the living planet. A thorough rethink is required, which has the courage to question even our most basic cultural narratives. Planetary Storytangling is my devised strategy of rethinking narrative transfer that I see as moving away from the human-focused to instead incorporate layered, multidimensional storytelling that includes all life upon this Earth. By interweaving Worlds, Natures and Cultures as part of a diverse species narrative, Planetary Storytangling encourages active voices and domains of agency that are other-than-human. Such a strategy has emerged already through a range of narrative transfers. Examples in literature include Richard Powers’ The Overstory which places trees as protagonists beside humans, and contemplates not only the perspective of nature but what it means to consider such an alternative viewpoint. Another illustration is Sasha Litvintseva’s visual narrative, The Stability of System which is based on the volcanic natural landscapes of Lanzarote that assumes the agency of storyteller throughout the film. By involving Planetary Storytangling in art, alternative existences, identities and voices can be explored to encourage out-of-the-box thinking and new approaches to understand our living planet, in an attempt to formulate what Bruno Latour calls “our common geostory.”[6]

With the emergence of Planetary Storytangling also comes a responsibility of language choice and dissemination. It is crucial to base our stories upon active and responsible discourse with an understanding of how knowledge is situated and words are framed within the contemporary environment. This is in line with Zoltán Boldizsár Simon’s belief that, “we fail to attempt to understand if we simply condemn and deprecate the occurrence of familiar words without making efforts to track the shifting meanings.”[7] For example, the Anthropocene as a term has been criticized as evolving to become synonymous with human consumption and destruction, straying away from its geological foundations and meaning. This, in turn, adds to reductionist viewpoints and the “crisis of imagination.” By choosing terms such as “ecocide” and “planetary annihilation” we can instead begin to acknowledge the planet as living, breathing and organic, reducing the distance between human and other species of the Earth. From this understanding, the language we choose is just as important as the tangling of diverse species narratives in order to achieve Planetary Storytangling. Planetary Storytangling can play an integral role in curating and framing our upcoming exhibition The Plantery Awareness Project. By using various art-forms that entangle voices, agencies, fictions and non-fictions through written, visual and sonic narratives, and by incorporating a diverse range of species, we can aid in encouraging a stepping away from the homo-centric as part of a conscious unlearning process, to instead embody the planet-wary. As Haraway states, “it matters what worlds make stories.”[8] By entangling and intertwining worlds, narratives and species stories within our exhibition through the strategy of Planetary Storytangling we can help disseminate and facilitate knowledge and experience that draws less from humans and more from others who reside on the living planet. In doing so we can re-imagine the world in richer terms that will allow us to find ourselves in dialogue with other species’ needs and other kinds of minds.

References

[1] Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press 2016, p.12

[2] Emmet, Robert. Whose Anthropocene?: Revisiting Dipesh Chakrabarty’s “Four Theses”. 2016 p.83

[3] Emmet, Robert. Whose Anthropocene?: Revisiting Dipesh Chakrabarty’s “Four Theses”. 2016 p.83

[4] Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press 2016, p.13

[5] Connolly, William E. Facing the Planetary: Entangled Humanism and the Politics of Swarming. 2017, p.33

[6] Latour, Bruno. “Anthropology at the Time of the Anthropocene: A Personal View of What Is to Be Studied.” The Anthropology of Sustainability, 2017, 35-49

[7] Simon, Zoltán B. “The limits of Anthropocene narratives.” European Journal of Social Theory, 2018

[8] Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press 2016, p.12

Further Reading

-Plumwood, Val. "Nature in the Active Voice." Australian Humanities Review, no. 46 (2009)

-Latour, Bruno. "Anthropology at the Time of the Anthropocene: A Personal View of What Is to Be Studied." The Anthropology of Sustainability, 2017, 35-49.

-Kerrigan, Dylan. "Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival Fabrizio

-Terranova, dir. 81 min. English. Brooklyn, NY: Icarus Films, 2017." American Anthropologist 120, no. 4 (2018)

Bibliography

-Bonneuil, Christophe. "The Geological Turn." The Anthropocene and the Global Environmental Crisis, 2015, 17-31

-Connolly, William E. "Facing the Planetary." 2017.

-Boscov-Ellen, Dan. "Whose Universalism? Dipesh Chakrabarty and the Anthropocene." Capitalism Nature Socialism, 2018, 1-14.

-Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press 2016

-Latour, Bruno. “Anthropology at the Time of the Anthropocene: A Personal View of What Is to Be Studied.” The Anthropology of Sustainability, 2017, 35-49

-Simon, Zoltán B. “The limits of Anthropocene narratives.” European Journal of Social Theory, 2018

0 notes

Text

Morally anthropocentric

By Claire van der Mee

The naming of a new epoch, namely the Anthropocene, coincides with the reluctant acceptance that humans have a direct effect on the Earth’s eco-system. This comprehension leads to an array of emotions ranging from guilt and hopelessness, towards hope for innovation and change. Whether identifying this age as the aforementioned sparks optimism or pessimism in human attitudes, those who admit to the title of the Anthropocene agree that this is due to mankind’s anthropocentrism. As we encourage everyone to take on the ‘Planet-wary perspective’ we are simultaneously a-ware that we too are bound by and limited to our human attitudes. [1]Yet perhaps it is precisely this anthropocentrism, this viewing and interpreting everything in terms of human experience and values, which we can use to our advantage in order to tackle the issues of the Anthropocene. Perhaps it is time for us as a human-species to become ‘morally anthropocentric’.

As a member of the human-species our abilities of perception are of course limited to those of the human. We are constrained by the impediments of our senses and know through scientific research that other species have a multitude of other capabilities; senses we can only begin to imagine understanding. Yet, like our other Earthly companion-species, we too are sentient beings. And it is through this sentience that we learn and grow and when applying extra sensitivity towards other-than-human species we can experience the sensation of their growth.

“The space of sympathy—which, in this case, is not to be interpreted as “feeling affection for” but as “feeling in harmony with”—needs to be evaluated according to the character considered in the comparison and the species involved in the comparison” (Marchesini, 2015).

When studying the non-human we can employ ‘critical anthropomorphism’[2]to achieve sustainability[3]within our relations to the things around us. Yet as Marchesini makes clear, this sustainability can only be achieved when regarding the things around us as becoming-with[4]rather than living-by. For example, think of the non-humans that you are familiarized with: a plant that lives with you in your home or a pet, such as a cat. One can sense if the environment is having a positive effect on this being. You may project human-emotions on these beings such as satisfaction, (dis)comfort, or sadness and perhaps attributing these feelings onto non-human species is flawed (within reason; their frame of reference is different than ours thus their reaction to our actions can be contextualized within completely different frameworks), but when applying this sensitivity (or critical anthropomorphism) one will recognize growth, stagnation or agitation.

This critical anthropomorphism can further be employed when considering the relations we have with the non-sentient things around us. In Hache and Latour’s text, Morality or Moralism (2010) they reflect upon Michel Serres’ text Statues and the myth of Sisyphus[5]and James Lovelock’s The Revenge of Gaia.

Serres draws attention to the fact that we as humans, when interpreting the myth of Sisyphus, are fixated on the narrative of crime and punishment rather than paying any attention whatsoever to the rock, which Sisyphus rolls up the hill eternally; the rock in all interpretations is a replaceable object.

“From the depths of the ages, from the pit of hell, from an abyss of suffering, the tale repeats: the thing returns!—and we Narcissuses speak only of him who rolls it away. What if, for once, we looked at the rock that is invariably present before our eyes, the stubborn object lying in front of us? . . .” (Serres in Hache & Latour, 2010: 329)

Lovelock, likewise, does an interesting appeal on anthropomorphism by renaming the Earth ‘Gaia’.[6]By personifying the Earth we enter into a complex relationship with Gaia; a relationship where we realize that our actions have effects and in order to have a healthy relationship with her we must act sensitively, sympathetically, critically and with morality and question what Gaia will do if we do not maintain a healthy relationship with her.

“Until this change of heart and mind happens we will not instinctively sense that we live on a live planet that can respond to the changes we make, either by cancelling the changes or by cancelling us. Unless we see the Earth as a planet that behaves as if it were alive, at least to the extent of regulating its climate and chemistry, we will lack the will to change our way of life and to understand that we have made it our greatest enemy.” (Lovelock, taken from Hache & Latour, 2010)

“Anthropocentric attitudes are limiting us in our ability to fully comprehend the critical turning point that our living planet is currently experiencing. In other words: we cannot solve problems with the same kind of thinking that created them.” [7]As Serres points out, it is time that we start including the rock into our narrative instead of stubbornly assuming that the rock is not a participant (or fellow-victim) in Sisyphus’ punishment. Diminishing our anthropocentrism starts by acknowledging it and realizing that we live-with not by the things around us. We as humans have an effect on our Earth, but the relationships we have with the things around us are also a part of what shapes us and makes us who we are. We may not be able to get the human out of our anthropocentric attitude but we can change our attitude. By applying our human-centered morals and values onto the things we are surrounded with (not by) and embracing these things as subjects within a mutual relationship, perhaps we can achieve a sense of urgency and realize that we need more sympathy and sensitivity towards every thing: anthropocentrism, but in combination with sustainable morality.

[1]This sentence is taken from our curatorial vision & mission statement

[2]The term ‘critical anthropomorphism’ comes from Marchesini’s text Against Anthropocentrism. Non-human Otherness and the Post-human Project, but he in turnhas taken the term from: Bekoff M et al (2002) The Cognitive animal: Empirical and theoretical perspectives on animal cognition. MIT Press, Cambridge

[3]“At the same time, every type of anthropomorphization needs to be evaluated in terms of sustainability on the basis of a robust scientific knowledge of the examined species, under a taxonomic, ecological and ethological profile” (Marchesini, 2015)

[4]“Becoming-with, not becoming, is the name of the game; becoming-with is how partners are, in Vinciane Despret’s terms, rendered capable.Ontologically heterogeneous partners become who and what they are in relational material-semiotic worlding. Natures, cultures, subjects, and objects do not preexist their intertwined worldings” (Haraway, Donna Jeanne. “Playing String Figures with Companion Species.” In Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, 9-29. 2016)

[5]From Greek mythology: Zeus punished Sisyphus and his punishment was to push a rock uphill for eternity: every time Sisyphus reaches the top of the hill the rock rolls back down and Sisyphus has to start again.

[6]Stemming from Greek mythology as well: Gaia is personification of Earth, the first deity from whom all others sprang and was born of Chaos.

[7] Quote from our Vision & Mission statement

References:

Marchesini, R. Nanoethics (2015) 9: 75. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1007/s11569-015-0220-7

Hache, E., and B. Latour. “Morality or Morlaism?: An Excerise in Sensitisation.” Common Knowledge 16, no. 2 (2010), 311-330.

Further reading:

Haraway, Donna Jeane. “Playing String Figures with Companion Species.” In Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, 9-29. 2016.

Serres, Michel, and Randolph Burks. Statues The Second Book of Foundations. London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Lovelock, James. The Revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth Is Fighting Back - and How We Can Still Save Humanity. London: Penguin, 2007.

0 notes

Text

PLANETARY PERFORMATISM

Merel Overgaag – 3997405

Due to our situatedness within time and space, human beings are not able to access the earth nor the universe as a whole. Therefore, everything we know about the planetary - about the world as a living planet including celestial bodies, multi-species and the biosphere - is formed by representations. It is a result of a staging of knowledge, grouped under the header of science or politics. Inevitably, these representations are framed. That is, the ‘representor’, whether it be a journalist, a politician, a teacher or a scientist, carries out a planetary narrative that is both contextually dependent and influenced by interest.

Examples of these performances of the planetary range from president Donald Trump who has openly denied global warming, on to the earth’s famous Blue Marble picture and the environmentalist activist connotation it got in the 1970’s. They range from history books presenting Darwinian evolution and others presenting Intelligent Design. Another example would be the late Medieval church resisting the Copernican Revolution by holding tightly to the geocentric world view. Or, lastly, cartographic attempts to map the earth, where certain continents seem to be strategically proportioned slightly bigger or smaller than their actual size. As a concept to understand how these phenomena are all forms of staging, I suggest the term Planetary Performatism. In the next sections I will contextualize this concept through the work of several authors.