Text

SPIRITED AWAY 2001 | dir. Hayao Miyazaki

#i was watching this tonight while swiping on hinge lol#and its making me think of last year when i felt exactly like this - abandoned and thrown into the adult world#no parents nothing#and the immovable loneliness of that experience and how well it is captured in this movie#especially in the landscape - its so liminal and etheral and sad and nostalgic#its that feeling of being completely utterly alone all by yourself#also known as adulthood

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

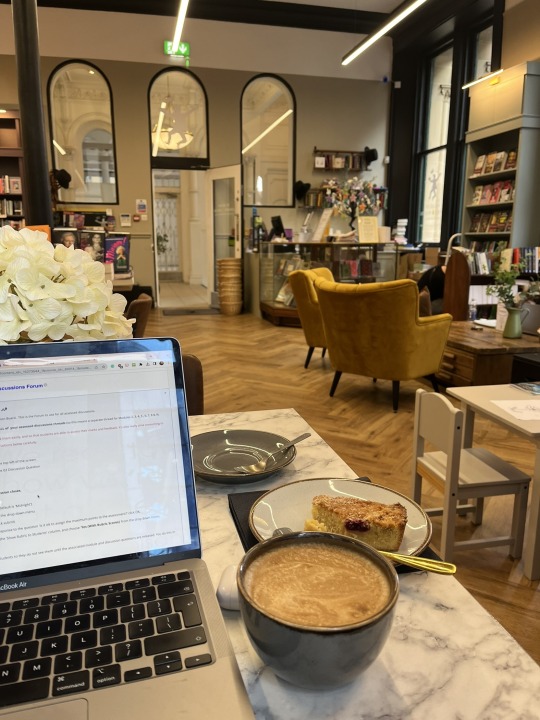

last week in food: i have been visiting my favorite cafes just to make work a bit fun... and occassionally buying myself sweet treats to eat in bed. today i got done with all my teaching for this week and i am kind of exhausted at the prospect of doing this for 9 more weeks... one day at a time *deep breaths* i am genuinely looking forward to flying home and vegetating at the end of this term

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

from the introduction to emily wilsons translation of the iliad

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

some other photos from this week: i rewatched kiki a few nights back and it resonated so much with me! (moving out, living alone, making friends, working *sobs*). I have also been reading ali smith's autumn and i loved the opening paragraph. and the third photo is from campus that i took on friday - a rare sunny day.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

some photos from last week. i signed up to teach 3 courses this semester (yikes) mostly because it would be nice to have some extra money. i have been making slides all week & it's been a bit exhausting. i am going to a coffee shop today to finish all the prep for the four tutorials i am teaching this week so that i can go back to transcribing tomorrow.

other things to do today include laundry and meal prep. at least i managed to sneak in some reading time this morning.

844 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s the true secret of life: We mostly do everything over and over. In the morning, we let the dogs out, make coffee, read the paper, help whoever is around get ready for the day. We do our work. In the afternoon, if we have left, we come home, put down our keys and satchels, let the dogs out, take off constrictive clothing, make a drink or put water on for tea, toast the leftover bit of scone. I love ritual and repetition. Without them, I would be a balloon with a slow leak.…Daily rituals, especially walks, even forced marches around the neighborhood, and schedules, whether work or meals with non-awful people, can be the knots you hold on to when you’ve run out of rope.

Anne Lamott, Stitches: A Handbook on Meaning, Hope and Repair

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

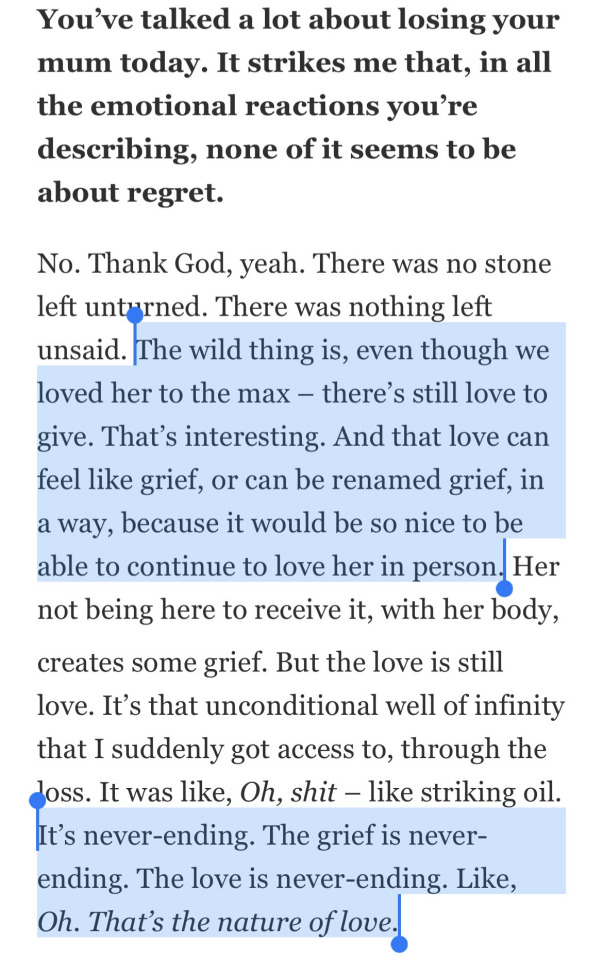

Andrew Garfield, in an interview with GQ

It's never-ending. The grief is never-ending. The love is never-ending. Like, Oh. That's the nature of love.

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

IN A WORLD WHERE BEAUTY AND ATTRACTIVENESS HAVE BECOME SO COMMONPLACE AND MUNDANE THE EXCEPTIONAL UGLINESS HAS BECOME DIVINE

132K notes

·

View notes

Text

more photos from my weekend trip to bath. i took a walking tour - learned a lot about how the rich used to live (ew) and visited the roman baths. fascinated by the 1000 year old water and ruins. really felt the passage of time. came back to manchester. now back to transcribing and teaching.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

a walk through sydney gardens (bath) this weekend. i also visited jane austen's house across the street. it was a gorgeous, windy day and i was both sad and happy, walking by myself through the gardens.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the essays my students write, I have begun to notice a common pattern. They are structured almost like Aesop’s fables. A moral seems necessary at the end — a kind of wrapping up, whichever way one chooses to look at it, like a prayer of gratitude after a meal, or an antacid tablet to aid the digestive process. Occasionally, I notice this in their poems as well, how the concluding lines must justify the existence of the lines preceding them. I have begun calling it “moralitis.” Without a text’s display of morality, we seem to be at a loss about how to justify its existence.

I offer these summaries as an outsider. I wasn’t born in America or England, and I wasn’t a participant in, or even a contemporary observer of, Anglophone literature departments. I am a postcolonial citizen reading the white world reading.

I notice what has been well-documented: How the creation of “area studies,” its support coming from espionage funds of the American government, led to the incorporation of literatures from these unknown cultures into white literature departments. I use “white” in the most matter-of-fact, self-evident way, without anger. That was what it was, a crowd of white writers, primarily male, squatting on syllabi for decades. They had written about things that struck their fancy: elephants, women, mountains, wars, a cup of tea, a day in the life of an unremarkable person. The syllabus-makers had legitimized their wandering. It was all right, the white writer could write about anything.

The expectation of the nonwhite writers was different. They were to be tour guides to their cultures, burdened with satisfying the intellectual curiosity of the white world. As Amit Chaudhuri wrote in his essay “I Am Ramu,” published in n+1, “The important European novelist makes innovations in the form; the important Indian novelist writes about India. This is a generalization, and not one that I believe. But it represents an unexpressed attitude that governs some of the ways we think of literature today. … The American writer has succeeded the European writer. The rest of us write of where we come from.”

In India — where I now teach in the English and creative-writing department at Ashoka University, about 45 kilometers from the capital city of New Delhi — what began with Salman Rushdie and Amitav Ghosh and Vikram Seth performing their roles as researchers for this new reader soon turned into a habit. Rushdie had tried to bring the linguistic energy of a whole culture into his representation of the Indian nation; Ghosh a Stephen Greenblatt-influenced understanding of history into the historical novel; Seth a sentimental appraisal of an India that had now disappeared. They were ambassadors of the Indian nation, often thought to be “representing” India just as artists and performers represented it in Festival of India programs abroad.

This wasn’t, of course, what Seth and Ghosh and Rushdie had set out to do; it was just how their work had been appropriated by this new and foreign readership. At the same time, any writer — or any text — that did not fulfill the purpose of national ambassador risked being ignored or rejected by the academics — whether in India or abroad — who were designing courses about postcolonial Indian literature.

The consequences of this are far-reaching. I looked at a sampling of English-literature question papers in Indian universities, primarily in the country’s provinces, where an American understanding of Indian writing has been imported without any skepticism or unease — this despite professors teaching courses on power and imperialism. Courses have titles like “Indian Writing in English,” “Postcolonial Literature,” “Indian Literature in Translation,” “Commonwealth Literature.” The questions asked of the students are revealing. “Analyze Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines as a critique of the nation-state”; “Write a note on Velutha as a Dalit character in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things”; “Discuss Things Fall Apart as a postcolonial novel.”

By contrast, in the same departments, William Blake was being studied as “a precursor to the Romantics,” W.B. Yeats as “the last Romantic,” John Donne as “a metaphysical poet,” Virginia Woolf as “a stream-of-consciousness novelist,” and so on. If the contrast in the pedagogical approaches to the “third world” literatures and Euro-American literatures is still not evident, one can just jog down to the early British literature paper, and then to the Renaissance.

Postcolonial texts seem to have two jobs in these syllabi: They either negatively illustrate some form of moral or social misconduct, or they positively represent a “marginalized” culture or geography. Ideally, they do both at once, often in the manner of a Live Aid concert. The genre chosen for such illustrative purposes is most often the Indian English novel and, occasionally, the Indian novel in English translation..

While academics often see themselves as correcting the oversights of mainstream publishing, in this case, the two have colluded, even if unconsciously. Just as Indian professors feel a responsibility to assign “representative” texts, so within Indian English publishing, editors and publishers — beneficiaries of various kinds of privilege — have felt a moral responsibility to present and represent those they considered left out of their understanding of literature. That category included the Dalit, the Adivasi tribes, occasionally women. To publish these “unknown” and “unheard stories” — phrases that attend many of the blurbs of books about these cultures and people — is their version of affirmative action, almost akin to wearing hand-loom textiles to register their support for the poor weaver.

This enterprise has had consequences besides the intended ones. The “Adivasi” and “Dalit” writers these publishers championed became just that to the reading public: one picked up a book by such a writer to become a better person. Juries giving prizes followed the same path: By giving a literary prize to someone they had identified as a subaltern, they were in fact trying to give the prize to the community the writer came from. This is the neoliberal’s version of the subaltern-studies project.

I have heard from some of these writers about their dissatisfaction in being read as Dalit writers alone. Manoranjan Byapari, for instance, tells me that, although he has benefited from the largess of intent, he and others want to be read as writers, like upper-class and upper-caste writers are — not given attention solely because of their status as disadvantaged. It is not difficult to see that this was a mimicry of what had happened in the West: the Indian writers’ responsibility to represent their nation had metamorphosed, here, into “marginalized” writers’ responsibility to represent their “local culture.”

Like the soldier fighting for the country, these writers are seen as fighting for their culture. (This attitude also explains why translation, a field ignored for decades, has suddenly become a moral mission — we must bring the “underrepresented” into the range of vision, even if it is only the range of vision of the English-reading world.) Meanwhile, choosing what books to read becomes itself a moralistic enterprise, a form of atonement. One must read postcolonial literatures to pay the guilt tax. It is a reading toll that the student of the white-literature syllabus is not asked to pay.

But the proliferation of readers who seem to have become addicted to paying this tax has created a new kind of marginalized literature: literature that does not serve the didactic purposes of the postcolonial survey course. For one thing, the postcolonial-literature syllabus continues to remain parasitic on the novel — it is as if our histories could only be held in the form of the novel, usually a fat novel, its girth approximately proportionate to the size of the country. The poem and the essay have been rendered minor forms here. Fragmentary and whimsical in nature, personal and private in style, they offer no assistance in the information-supplying service that the postcolonial syllabus is expected to perform. The few poets who are studied, if at all, have been given a place on the syllabus for their founding-father status. Unlike the novel, where new work is regularly called for duty on the syllabus, contemporary poetry (say, Indian English poetry) might be imagined to have gone extinct.

The same question should be asked of the postcolonial syllabus. While the moralizing mission might appear admirable, these courses ignore all literature that does not fit its agenda. What else explains the utter absence of comic novels in the postcolonial course? How else to explain why Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s novels, particularly Aranyak, are not taught? Or why Amit Chaudhuri’s novels, with their life-loving energy, do not find a place here? Or why stories and novellas about provincial life, such as we find in the magical writing of R.K. Narayan, have not yet been included? Literature about the moment, about the everyday, is rejected: Comedy, laughter, pleasure — the postcolonial subject must not be seen partaking of these contraband things. The syllabus often reminds me of what our hostel matron used to say: Don’t smile and show your teeth when praying.

Here is the space where the syllabus remains to be decolonized — not through substitution, but addition. A course on British modernism will include a novel or two about a day in the life of a white man or woman, such as we find in James Joyce’s Ulysses and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. But a young Indian student’s life on a day in July — masturbating, thinking of becoming a “famous poet,” walking around London with his uncle, eating at a restaurant and fighting with him, as we find in Amit Chaudhuri’s comic novel Odysseus Abroad — is judged too self-indulgent for a postcolonial course, even as it is not hard to see that this life in the novel, if anything, is the postcolonial subject’s condition.

What I am seeking is for the postcolonial-literature reading list to be liberated from its current status as “minor literature.” I do not use this term like Deleuze does, but rather to describe the sense within English-literature departments that these are to be studied as Ur-manifestos and histories of repression and suffering, and that all other kinds of writing are to suffer the same fate as banned literature: to remain ignored and unread. A course on Modernism, for instance, should include writing and art from non-Western cultures, where books exist side by side, related by temperament, aesthetic, or form, and not because of a United Nations idea of representation.

Literature in the postcolonial syllabus should surprise the student, not just confirm and illustrate “theories.” This, too, should be part of the decolonizing-the-syllabus mission: to dismantle the binary between postcolonial writers as content writers and Western writers as experimenters with form. Only then can we begin to address the “moralitis” of my students, which, although it might seem at first harmless, or even praiseworthy, turns out to entail a troubling indifference to pleasure and beauty, to ananda (joy and delight), which is often the backbone of India’s modern literatures.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

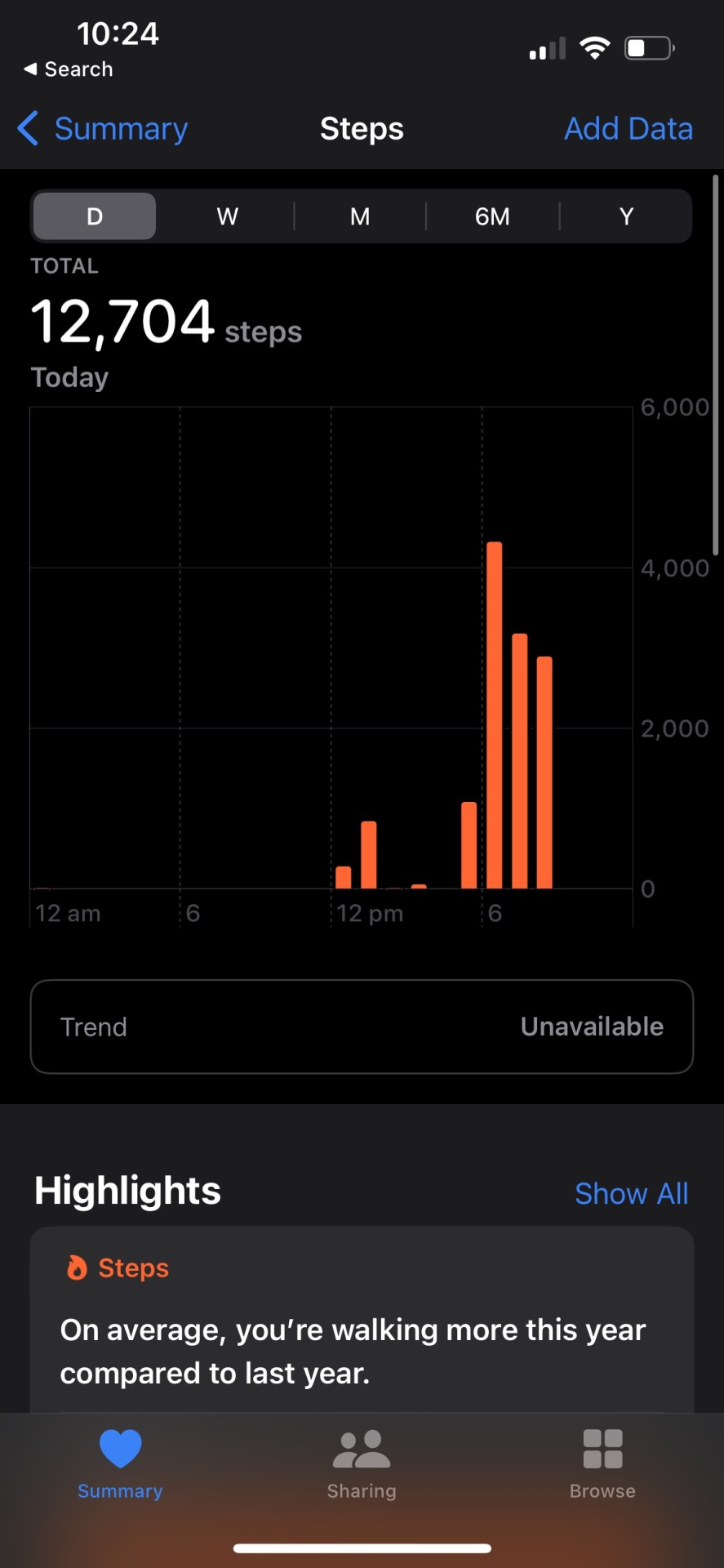

some more snippets from today. i saw these flowers in a dumpster this morning and it made me a bit sad (also MOOD). the sunset photo is from my mental health walk (i get really anxious in the evenings and the only way to manage it has been going on very long walks).

4 notes

·

View notes