❋ Sharing fresh perspectives from diverse youth voices. A blog in progress, welcome to the future

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

PSA: Book As Multimedia Interface 'Kill' The Authors and 'Give Birth' To The Readers

By Promise

Partially Powered by Chat GPT

What is a book? What is the definition of a book? The answer can vary as technology keeps challenging the conventional idea of a book. It does not have to be physical; it can be audio and electronic stored in the “cloud.” Our electronic devices allow us to access books from different formats and media easily. Amaranth Borsuk, an American poet and scholar, is curious about the evolution of books, and she wonders how books as interfaces will lead us in the future. Borsuk, therefore, wrote The Book to explore the book's history, technology, and future as a physical and conceptual object. The Book itself is a physical representation of this exploration, with its pages containing a mix of traditional printed text, digital images, and interactive elements such as pop-up pages and QR codes that link to online content. The Book is divided into five sections, each of which focuses on a different aspect of the book's evolution. These sections cover topics such as the earliest forms of writing, the development of the printing press, the rise of digital media, and the potential future of the book in an age of rapidly advancing technology.

The last chapter of Amaranth Borsuk's The Book, titled Colophon or Incipit, is a reflection on the book as a physical object and the role that it plays in our lives and culture. The title of the chapter refers to two traditional elements of a book: the colophon, which is a statement at the end of a book that provides information about the book's production and publication, and the incipit, which is the opening words or phrase of a text. In this chapter, Borsuk reflects on the many ways in which books have been used throughout history, from sacred texts to works of literature to scientific manuals. She notes that while books have traditionally been associated with authority and permanence, they are also mutable objects that can be transformed by their readers and the contexts in which they are read. Borsuk also considers the future of the book in an age of digital media and explores the ways in which digital technologies are changing the way we interact with texts. She argues that while digital media have certainly had an impact on the way we read and write, the book as a physical object remains an important and valuable part of our cultural heritage.

Brosuk’s Colophon or Incipit examines the idea of books as interfaces in the future. With technology, readers can now interact with the book with multimedia to enhance the experience of understanding the books’ ideas. As Brosuk points out, “consumers of books have never been passive…both we can the texts we read have bodies, and it is only when they come together that book takes shape” (43). Technology’s flexibility allows readers to interact with books actively more than ever which reminds me of Roland Barthes’s essay The Death of the Author. The essay is a theoretical exploration of the relationship between the author, the reader, and the meaning of a text. He argues that the author's intentions do not solely determine the meaning of a text but rather emerge through a dynamic interaction between the reader and the text. Barthes's essay is a dense, philosophical work that is primarily concerned with ideas and concepts rather than with the physical form of the book itself.

youtube

Overall, Both Barthes and Borsuk deal with similar themes related to the meaning and interpretation of literature. Books as multimedia interfaces “kill” the author because “book” or “text” can exist in various formats of multimedia for readers or consumers to enjoy. Consumers interact with “text” differently; therefore, the meaning of the “text” vary depending on how consumer interact with multimedia which further prove Barthes’s theory of “the death of the authors,” it can also interpret as the birth of the readers or consumers.

Works Cited:

Borsuk, Amaranth. The Book, MIT Press, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central,https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/west/detail.action?docID=5376610.

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Image, Music, Text, translated by Stephen Heath, Hill and Wang, 1977, pp. 142–48.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA: Be Mindful of Whatever You Are Seeing Right Now on Social Media!

By: Promise

The Problem of Social Media

Criticizing social media has been a hot topic as it affects people’s well-being and spreads misinformation. But we rarely go deep into thinking about what social media consists of and what exactly affects people’s well-being and information. We post photos or videos on social media for our friends to see, sharing our moments because we, as human beings, are social animals; therefore, we care about how others perceive us. With photos and other media, social media creates a toxic environment for us to crave others’ attention and validation. This eventually makes us self-conscious and anxious, which can be detrimental to our mental health.

The Problem of Photography

Susan Sontag is an American philosopher, activist, and critic; her book, On Photography, theorized photography's philosophy while criticizing it. In Plato’s Cave is the first chapter of this book. The title is a reference to Plato’s allegory of the cave. According to Plato, life is like being chained up in a cave; we are forced to watch shadows flitting across a stone wall; therefore, we think those shadows on the wall are the actual object in the world. It seems natural for Sontag to compare these shadows to photographs, claiming that photography limits people’s view of this world and shapes how we see it. As Sontag argued, “photography implies that we know about the world if we accept it as the camera records it” (23). But life and time will continue; photography produces a reality that lives in the past. It appropriates reality to create an image of it, causing individuals to derive meaning solely from images rather than interacting with the real world. As technology evolves, social media repeats and re-enforces the same thing as photography.

youtube

In Plato’s New Cave – Social Media

Sontag’s criticism and theory on photography are still relevant today. As cameras, mobile devices, and the Internet become an entirety, they produce what we cannot live without in today’s modern society — social media. I believe that social media is the new Plato’s “cave” we live in, as we are convinced that whatever is on social media is the ultimate “truth.” Compared to photography, social media consist of more element. It combines photographs, videos, audio and texts; its purpose is to facilitate efficiency in human communication. My concern is that with social media, we will stop thinking critically about the information we consume and unconsciously embrace the “shadows” on the wall (our phones) as reality. Which resulting many people being “stuck” in the cave longer and longer. Ultimately, we lose ourselves in the sea of information, which detriments various aspects of our lives. This negative result of social media resonates with Sontag’s points on photography, “the camera’s rendering of reality must always hide more than it discloses” (23). This reflects on today’s social media as a monolith that deludes reality even more as we spend more time on it.

Getting Out of The Cave

This new cave built from social media is scary, but it does not have to be. We can easily get out of the cave if we take a second (stop scrolling or turn off the devices) to think critically about the photos, videos and texts. Raising questions about the post: Who posted it? Why did they post it? What is the intention behind the post? Is the post beneficial to my knowledge and well-being? The start of this questioning process is the start of getting out of the cave; this process takes practice and time as we are all stuck in this cave for various levels, but first: Be mindful of whatever you are seeing right now on social media!

Works Cited: Sontag, Susan. On Photography. Penguin Classics, 2008.

0 notes

Text

PSA: Shape yourself through self-writing online

By: SUMMER

How do we come to understand ourselves? In Theresa Sauter’s article, “‘What’s on your mind?’ Writing on Facebook as a tool for self-formation,” she talks about how self-formation practices can help shape our perception of ourselves and establish guidelines to live by. Sauter refers to Foucault, who argues that the self is fluid, ever-changing, and intertwined with other entities.

What do diaries and status updates have in common? Self-writing is a practice of self-formation that has been around forever. Something like journal writing is fully private, allowing me to organize my thoughts with the comfort of knowing that no one will ever see what I write except for me. However, self-writing can be public, too (anyone can start a blog like this one). Foucault states that "Online self-writers... write to “show [themselves],” to project [themselves] into view, to make [their] own face appear in the other’s presence." Philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, paraphrased by Abeba Birhane, offers a similar take, declaring that we need others in order to construct a solid self-image. Thus, social interaction and validation are necessary to our existence.

Sauter looks at self-writing on social networking sites (SNSs), and specifically Facebook status updates. Although her article was written in 2014, her arguments are still relevant today. She notes how communication styles in modern times have shifted, causing a lot of self-writing content online to become much shorter in length. I think Foucault and Bakhtin’s points can be used as an explanation here. Short pieces of writing, like status updates or Tweets, are easy for people to consume. Readers can immediately form an opinion and leave likes or comments. Sauter quotes Marwick and boyd, who note, "people are rewarded with jobs, dates, and attention for displaying themselves in an easily-consumed public way." We are always re-shaping ourselves based on the feedback of others; we know that the faster someone can read through a post we make, the faster we can receive that feedback.

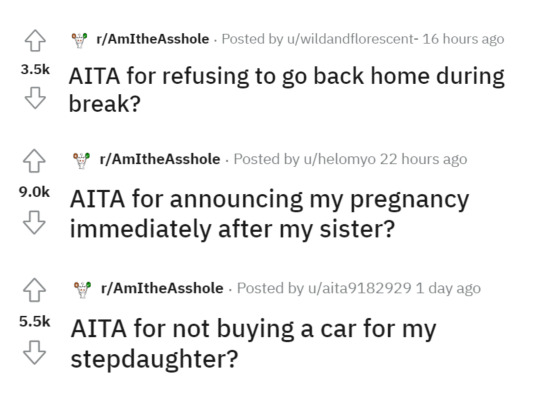

Exposed!! Reddit is a hub for advice-seeking and confessionals online, which I was reminded of when reading Sauter’s article. I used Reddit obsessively while completing university applications a couple years ago, spending hours scrolling through “Should I study Business or Arts?” and “Thoughts on School A?” threads. Platforms like Reddit allow anyone on the internet to give you advice, though this makes it hard to differentiate between the helpful and the trolls.

Asking for advice is one thing, but it surprises me that people can admit to their mistakes (and often embarrassing or serious ones at that) online among all the trolls. I think Gen Z kids especially have a tendency to overshare on social media because, growing up with screens, we’ve gotten too comfortable online. Nevertheless, self-exposure can be a good thing for people. Users can “reveal their faults to others, engage with their conduct and thus establish ways of guiding future behaviour,” according to Sauter.

A great example of this is the “Am I the Asshole?” (r/AITA) subreddit, with over 6.3 million members. Users post about a conflict they were involved in and others let them know if they were in the right or if they were, in fact, the asshole. I guess people want feedback and opinions from people who won’t just tell them what they want to hear; I can see how that brutal honesty can be valuable and refreshing. On the other hand, when we know we're right, we might be motivated to post on a page like r/AITA to get reassurance from as many people as we can get, even strangers.

Overall, regardless of the platform we write on, Sauter states that we “form relations to self and others by exposing [ourselves] to others and obtaining their feedback.” Once we know what people like about us or what we did wrong, we are able to make the corresponding changes to our lives and continuously pick out the aspects of ourselves that we want to stand out.

So… what did you think of this blog article? Asking for a friend.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA: Human Connection and the Invention of the Internet!

By: Annauncement

Ray Tomlinson holding up his creation, the @ sign, posing for the Guinness World Records.

Computer technology has advanced fast – seventy years ago, a computer was the size of a room and performed only calculations. Now, we carry the largest, most interconnected web of networks and information the world has ever seen within our pockets. Show a smartphone to someone working the Apollo Guidance Computer in the 1950s, and you would cause quite a shock!

The Internet is no different in this regard. The article “How the Internet was Invented” by Ben Tarnoff explains how the invention of the Internet evolved from a military project to the ‘vast and formless’ digital universe of today. To simplify immensely, the Internet began when the US agency ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) wanted to utilize a wireless network to communicate with their wired computer system to serve soldiers on the front lines anywhere in the world. Eventually, in Silicon Valley at a Rossotti’s Alpine Inn in 1976, a protocol was successfully implemented that allowed both wired and wireless networks to communicate.

What happened next?

APRANET - as it was called - was a military creation, and since the USA military was everywhere, the APRANET was designed to run everywhere. APRANET was designed for connection, and this flexible protocol meant that “channels as dissimilar as radio waves and copper telephone lines” could communicate large distances.

Despite this new governmental power, the Internet only took off once the civilian population started using it. Even Don Nielson, one of the original ARPA researchers who first implemented the program in 1976, said, "... [it] was absolutely startling to me: the clamor of wanting to be present in this new world.”

Rossotti's Alpine Inn

What made the Internet so popular?

The answer is surprisingly simple – emails. In 1972, the first ‘email’ had already been created by a Ray Tomlinson to send messages between computers in the same network. When APRANET was implemented, emails could now be sent across multiple networks, reaching far beyond the closed systems of APRA and its military research based purposes. Fifteen years later, this popular form of sharing information led to people desiring a permanent, simplified ‘space�� for digital information; and thus, the World Wide Web was created.

Why did emails popularize the Internet?

Alongside the APRANET, emails offered something that humans crave on a fundamental level: connection. Emails showed what the Internet could become – a place to communicate, share news, and even make friends with new people. With the creation of the World Wide Web and household laptops, an easily accessible digital space was born for the sole purpose of sharing information and connecting people together; first for scientists and institutions, and then the rest of the world. This space was the World Wide Web, and with it, we had created a seemingly “… boundless, borderless digital universe…”, all just to connect and learn from each other.

Humans are social animals, needing communal connections to survive – look it up, you can die from loneliness! And the Internet provided a new, vast source of connections. Fast paced communication was not new in the 1900s – radios, television, and phones had been around for decades – but the Internet could move far beyond these technologies. APRANET’s seamless transmission of data between networks meant that what medium we communicate with can be as equally huge – audio, visual, textual, even program based. The Internet could connect us in any number of means, and connect with people we did!

The Internet is by no means a utopia place of friendly people all looking to learn from each other – neither is our society, after all. However, the lesson to take away is that between using the APRANET only to fight wars, or making a digital community where we can explore our world and each other, we chose the latter. It is now a place where, among other things, diverse youth voices such as yours truly can gush gleefully about the Internet’s history and human connections.

And really, isn’t that wonderful?

---

PSA - Check out the first website ever made!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA: VICTIMS' VOICE MATTERS AND THEY DESERVE TO BE HEARD BOTH ONLINE AND OFFLINE!

by: promise

Social media is an important platform to let people’s voices get heard, especially for groups of oppressed people. It helps activism move to digital space, which helps raise awareness of specific issues more broadly. Jinsook Kim’s article – Sticky Activism articulates the importance of digital activism. In this article, Kim illustrates the Gangnam Station Feminicide and uses the interview to analyze how this incident became a pivotal moment to help raise awareness around gender, misogyny and feminism in South Korean society.

What happened?

The incident happened in the Gangnam District – the central business center of Seoul. The murderer, a Korean man, had stabbed a woman to death in a public bathroom near Gangnam subway station. The media initially reported it as a “random killing” because, allegedly, the murderer did not know this woman. However, because the victim is a woman, many Korean women have expressed concern about Korea’s long-rooted misogyny culture, and ultimately has become an activism both online and offline.

Copy from Los Angles Times, 2016.

Sticky Activism:

After the incident, massive vigil events were hosted across the countries, especially in the Gangnam District. People who came to the vigils wrote their thoughts and prayers on sticky notes and stuck them in public spaces to express their emotions to the victim. Many of these sticky notes are written by women who are survivors of sexual assaults and abuse, which helped motivate more and more discussion regarding Korean misogyny culture online. Those sticky notes help raise awareness of people in Korea, even internationally have become a form of activism; Kim coined this “Sticky Note Activism,” later “Sticky Activism.” Kim uses the word “sticky” to emphasize the “stickiness” of the movement in scholarly discussion. According to Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green, "stickiness" relates to a media's ability to capture and maintain individuals' attention and involvement. It is sometimes used in contrast to the concept of "spreadability." Sticky Activism eventually evolved to be both sticky and spreadable with the help of both online and offline.

Opinion:

Kim’s article regarding sticky note activism in response to the Gangnam station incident teaches us how to make our voices heard online and offline. Victims' voices matter, but how we can let them stick and spread is the question that digital activists need to evaluate. Sticky activism gives us a perfect example of what modern-day activism should be. From sticky notes to online discourses, they eventually grasped the authorities’ attention to embed laws and regulations to protect women from sexual assaults and abuses. Sticky note activism is undoubtedly successful. It combines the merits of online and offline activism, which can spread people’s voices, and those voices can stick to their minds.

Copy from BBC News, 2022.

Sticky activism should be the future form of activism. And here’s why:

There are pros and cons when it comes to online and offline activism. It is a good idea that activists nowadays utilize social media to raise awareness on specific issues. Because social media is easy to form an activist movement by creating accounts and hashtags, online activism can grasp more people’s attention quickly due to the spreadability of social media. However, online activism nowadays is saturated, especially as numerous news and information updates every minute on social media, and people become less empathetic toward tragedy and victims. Resulting in people hardly resonating with online activism; thus, doing activism online is not enough to stick in people’s minds; people can use their fingers to scroll it away. Unlike online activism, offline or in-real-life activism can grasp people's attention immediately, for instance, protesting, walking outs, and making signs because those are real people fighting real unjust issues; people have more empathy toward authenticity and living beings. However, this conventional way of activism is limited geographically. They can only raise awareness on local issues but can’t travel or spread out internationally to grab more people’s attention. Sticky activism learns from both online and offline activism. It makes victims’ voices heard online and offline. It helps the offline emotion and authenticity shift online to raise public awareness of the issues.

Overall, Kim’s essay gives us a great analysis of sticky activism - - combines both online and offline to make movements spread and stick. We all understand that victims' and oppressed social groups’ voices matter. But how can we let the voices be heard? I think sticky activism has already answered, utilizing online and offline resources because those voices deserve to be heard online and offline.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA: You should try and discover yourself!

By: Ana Milojevic

Comic by Peter Steiner, 1993, The New Yorker

In 1993, Peter Steiner would famously coin the adage, “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog!” It might seem reminiscent of the old warning parents would give their children about how anyone can pretend to be anyone on the internet (mostly, of course, too young vulnerable girls about male predators).

However, the adage was never meant to be a warning about stranger danger, and in fact, early audiences took it in a wonderfully optimistic way. In response to the comic, Lisa Nakamura writes that the internet offers, “… unprecedented possibilities for communicating with each other in real-time, and for controlling the conditions of their own self-representations…”. what she called a form of “computer cross-dressing”. The idea of using the internet as a way to escape the confines of our bodies – or rather, the societal norms enforced on our bodies – seems a wondrous ideal.

Legacy Russel’s ‘Glitch Feminism’, as both an essay and a concept, take this ideal and interprets it through the lens of gender. Russel speaks of the binary-gender system as ‘a set of rules and requirements that her body is forced to play out, and that to refuse this performance – this compliance – she inhabits a sort of glitch in the system. By using the internet and its anonymity, she is capable of embodying this non-performance and discovering herself beyond the enforced boundaries of her body.

Does this mean we’re running away?

This should sound like a familiar tune to many people who grew up alongside the internet, using it as a platform to become someone else during times when being you was too difficult. I too, felt the need to craft a different persona so I would not have to confront myself. However, Russel does not speak of ‘escape’ – and this might be confusing. After all, are we not escaping our ‘real’ life when on the internet?

To suggest that what occurs on the internet is not ‘real’ is a fallacy – half our world runs on streams of data that most of us will never see, hear, taste, smell, or feel. The internet is not full of empty voices and faceless algorithms, but rather a living breathing thing comprised of millions of people just being people. Russel’s relationship with the internet is acknowledging it as a place of connection, a place of being, and recognizing how one can change who they are and be who one wants to be in the digital world. Our world is more than the physical bodies we inhabit.

What is good about this?

The important lesson to learn from Glitch Feminism is recognizing the power of an in-between space – because the internet does not bind a person to their physical body, a person can explore many avenues of existence, being something that is in between the binary spectrum of the physical world. This is not about creating a great leveling field, where a person can pass as belonging to more privileged groups. Glitch Feminism has no interest in passing or equalizing, and instead works on finding new ideas, new ways of ‘becoming’ one’s self. It knows that the gendered binary is ‘imaginary, manufactured, and commodified’, and rejects it in its totality.

What do you do with it?

To young readers discovering themselves, the ideals of Glitch Feminism offer you the digital space as a way to discover yourself and amplify your identity. By this act of self-definition, we create a stepping stone, an internal realization that we can move forward to a world free from the gender binary. We inject ‘positive irregularities’ into a world filled with carefully tailored ways of being, and create malfunctions within the system that make spaces for new forms of gender experience. Ultimately, we become this Glitch, throwing the current system absolutely off, and continue to play, experiment, and try, all through the internet.

---

(PSA – The internet awaits, but always be responsible)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA: Be conscious of biased algorithms!

By: SUMMER

I recently read “A Sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis-)Recognition”, a chapter in the book Duty Free Art by Hito Steyerl. She discusses the growing issue that data analysts face in a world where there is an overwhelming amount of data to go through - how to differentiate between signal and noise. She argues, “Vision loses importance and is replaced by filtering, decrypting, and pattern recognition”.

I thought that her idea applied to us as media consumers and social media users on an everyday scale in a similar way. We’re being hit with so much information at all times that our brains sometimes go on autopilot, constantly deciding what’s worth paying attention to and what has to go. On social media, we end up curating a stream of content that perfectly caters to our interests and shows us what we believe is important - that’s us separating signal from noise.

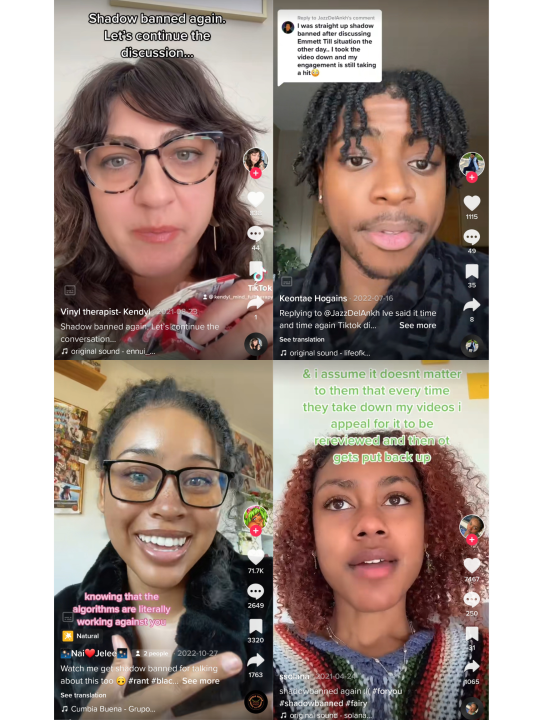

Who does social media actually care about? Steyerl references a mythical Ancient Greek story in which “affluent male locals” produced actual speech, while “women, children, slaves, and foreigners” were just noise - annoying and irrelevant. I thought of our last Digital Humanities class, where we talked about how social media platforms function and whose interests they prioritize. While we do have some control over what we want to see on our feeds, we concluded that biased algorithms maintain feeds that are dominated by people who are white, able-bodied, conventionally attractive, etc. Some of my classmates noted how marginalized communities, like LGBTQ+ folks, are being censored and shadow-banned on social media. It sounds an awful lot like a modern-day equivalent of that Ancient Greek story.

TikTok users speak out about their posts being wrongly shadowbanned and flagged for violating Community Guidelines.

Not to burst your bubble... “Dirty data” is a term that Steyerl uses, which can mean inaccurate and inconsistent data, but should also be understood as “real data” that “documents the struggle of real people with a bureaucracy that exploits the uneven distribution and implementation of digital technology”. What she means by this is that entire groups of people are ignored - “not taken into account” - because these digital and social structures simply do not work in their favor. We're at fault here, too - the downside of having that control over curating our feeds is that we tend to trap ourselves in a bubble. We make connections that reinforce our existing worldviews and cry “dirty data!” at the stuff that doesn’t fit the mold that we’re comfortable with. Organizations like Logic are recognizing this issue and making plans to use their platform to amplify the voices of typically silenced groups of people, like trans and Indigenous writers. Action like this is important in broadening our perspectives and making room for content outside of the bubbles that we and our biased algorithms have worked together to create.

Data vs. reality What are the dangers of relying too heavily on these algorithms to analyze data? To what extent do the patterns they find correspond to actual reality? In the chapter, Steyerl talks about automated apophenia: computers perceiving connections in data where there aren’t any. She prompts us to consider the real-life consequences of making decisions based on these phantom patterns. In recent years, tenant screening technology used in selling and renting homes has been threatening housing equality due to its programmed bias. This article from Curbed explains how the problem boils down to tech experts designing these systems “in a vacuum”, without any knowledge on civil rights or social implications. The NSA’s SKYNET program that Steyerl references in his chapter is the same type of issue on a larger, deadlier scale.

I won’t deny how important technology is for our everyday functioning, but it isn’t perfect or limitless by any means. Supposedly objective and fact-based algorithms often become reflections of our own human biases. But if we’re the ones who wrote them, then we can be the ones to recognize their flaws and work towards fixing them!

11 notes

·

View notes