Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

When design doesn’t work out the way you planned: a critical look at UCL Academy

UCL academy (Image 1) looks nothing like the school I went to (Image 2). At the very core of the design was an intention to facilitate education; corridors, classrooms, study spaces, they were all designed with purpose. By contrast, my school was a large, converted Georgian house which has been added to and adapted over the years (a rather common school ‘type’ in London). Despite, the nuisances of being in a converted building, for the most part I felt my school functioned well. UCL academy is a new building, constructed with lofty ambitions on how children could be educated better, but fails due to the ridged requirements of a nation-wide school curriculum. Was it too ahead of its time? Or did the design fail to truly consider the highly programmed requirements of the user? What happens when design doesn’t work out the way you planned.

UCL academy is full of contradictions; it’s both grand and inconspicuous, encourages open plan learning, but segregates students into houses. There is a two corridor system intended to ease flow through the building at peak times yet the children (understandably) aren’t keen on the outdoor corridor in Winter; and the open plan study spaces and mixed use classrooms often don’t fit the needs of the subjects. The lecture theatre felt more like a training space than a meaningful addition.

This building in plan, may have been impressive and interesting, but perhaps those drawings are never sufficient at predicting the lived experience of the building with its inhabitants. UCL academy still functions as a school and a rather pleasant one at that; but the student have had to make the design work for them, rather than the building functioning perfectly for the inhabitants.

References

Image 1 https://www.penoyreprasad.com/project/ucl-academy/

Image 2 https://www.writeopinions.com/lady-margaret-school

0 notes

Text

Representations of power and democracy in the architecture of law

London isn’t a city with a tradition of many well-defined districts, it’s a city that has grown in a sprawling organic nature with arteries and veins extending from its two founding chambers: the city of Westminster, home of power and politics; and the city of London, the centre of commerce and trade. But at the boundary of these two cities sits Legal London, a collection of buildings and an archaic street network where a large proportion of the city’s legal sector reside; a hive of activity, decision and drama which paradoxically feels quiet, private and a world away from its central location.

Arriving outside the Royal Courts of Justice (RCJ) on Fleet street you are confronted by the power of history and representation, even Fleet street itself is canonized in London’s narrative. Ignore the crass metal barriers that mark the entrance and its ‘security’ measures and RCJ is still a stoic and stern building. It looms overhead in a Victorian gothic style, heavy with stone, sharp with turrets; more than a little aggressive but with a commanding beauty that declares ‘I am important’.

Image 1: ‘I am important!’ Royal Courts of Justice, London (ref1)

Buildings always raise issues about the relationship between architecture and society and the exterior facade of the RCJ is no different. Though there are many the windows are small and inset, suggesting that this is not a building to see into but rather one that can observe better the outside world. The elaborately carved porches reflect the extensive amount of money spent of its construction and the heavy iron gates remind you that though you may enter, you are not in control.

Walking through to grand hall, opened to a triple-height there is a moment of breathing space before you look around and see a warren of corridors leading off the central hall, where do they go? You have no idea.

Lawcourts generally are highly contrived (programmed) buildings designed to execute a specific function. They are spatially organised in a system of private rooms and long corridors, to disorientate, segregate and implement ‘the law’. Through this layout they give the inhabitants, an advantage and therefore express a formal and hierarchical system whereby the state holds all the power.

As the highest representation of law in the United Kingdom, the architectural form and configuration of the RCJ comes to signify a mechanism for social control. You only need sit in a courtroom for five minutes; with its oppressive interior, old books covered in plastic, the smell of must and acoustics so poor you wonder how the judge could hear the defendant talking a mere 2 meters away to understand this is a mechanically solid institution, that hadn’t had to adapt because it mandates the strategy and that you, the citizen, may sit within a milieu of democracy, but you are most certainly on the wrong side of history.

An attempt at metaphor has been implemented into to the design of many legal institutions, who seek to reflect a new identity of an open and transparent democracy.

Image 2: ‘Can materiality ever underpin an embedded sense or power? Reichstag, Berlin Norman and Foster’ (ref 2)

Through materiality, buildings such as the Reichstag in Berlin, or the Patzcuaro ‘oral’ criminal court in Michoacán, Mexico have tried to subvert centuries of power dynamics that position the state against the people. It begs the question; can material ever underpin high programmed systems and an embedded sense of power?

Image 3: ‘Can materiality ever underpin an embedded sense or power? Oral-Criminal Court in Pátzcuaro, Taller de Arquitectura Mauricio Rocha + Gabriela Carrillo (ref 3)

In a similar vein, such a critical review asks, can the application of space syntax theory disrupt sufficiently to create new systems of justice? Or is power, who holds it and its representation so systemic that configuration becomes obsolete? Whilst, it may be idealistic to argue that space syntax could reconfigure social structures of power; it is possible that its application could initiate a conversation and therefore a consciousness which over time may shift perspectives.

ref 1: The Royal Courts of Justice https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Courts_of_Justice

ref 2: The Reichstag https://medium.com/@elebias/the-reichstag-building-in-berlin-a-modern-parliament-in-a-historic-building-3a9623a7c3b1

ref 3: Patzcuaro Oral Court https://www.archdaily.com/906832/iturbide-studio-taller-de-arquitectura-mauricio-rocha-plus-gabriela-carrillo

0 notes

Text

A new approach to building. Reflexive, adaptive, lived.

We readily accept that biology and nature exist in systems of feedback, evolution and adaptation, but we are less inclined to understand architecture in these terms despite its relationship to social organisation and culture. Walking around the Francis Crick institute, a biomedical research institution, I found myself wondering – what is the life of a building? And if we view architecture as a living system of feedback and response, what should that mean for the architectural design process?

Architects often create buildings in deterministic models, for them, the life of a building begins with a brief and ends with a completed structure. Whilst there is a consideration for user, with affordances (Gibson, 1979) built into the design, rarely does the feedback loop endure past the day that the user enters and the building becomes wholly his domain.

But architecture is living and it is adapted by the user: the plant pots that come to reside on desks, the posters that are stuck over windows to stop people looking in, and equally the building shapes the behaviour of the inhabitants there’s the kitchen that isn’t used because there’s not enough space in the fridge for your lunch, the chair cluster that everyone wants to congregate at because it has the perfect view over London; we generate habitus (Bourdieu, 1977) in our buildings, an embodied sense of ‘just what’ functions in architecture once we’ve had the opportunity to live in it.

As Alan Penn argues, we cannot separate structure and agent (building and user) in our analysis of architecture (Penn, 2008/9), and I would argue that analysis should persist beyond the completion of a building because this is when the life of a building really comes to be. If we accept that a building lives with its user, and that space and society are shaped concurrently, then we cannot expect to provide for every eventuality within the floor plan. Buildings need to be continuously evaluated and adapted with user for use.

The Francis Crick institute is exemplary of an architectural approach that maintains a feedback system between architecture, architect and user. Despite being highly specialised and strongly programmed, HO+K designed the buildings and imbued it with the capacity to adapt and be adapted.

“ Now we know how the building is used, there will be a second wave of building improvements that will fix that.”

The Francis Crick Institute can be summarised as, “[a] research centre without hierarchy or departmental divisions. A place with open doors for impromptu conversations and idea sharing. An environment where collaboration trumps competition and where the work of one researcher is intimately connected to that of her peers” (HO+K, 2019). This ethos is embedded in the infrastructure of the building and of its users, and the design reflects this philosophy. Having an adaptive design and an approach that encourages a continuous feedback between structure, agent and design has facilitated the goals of the institute to bring together outstanding scientists from all disciplines (Crick, 2019).

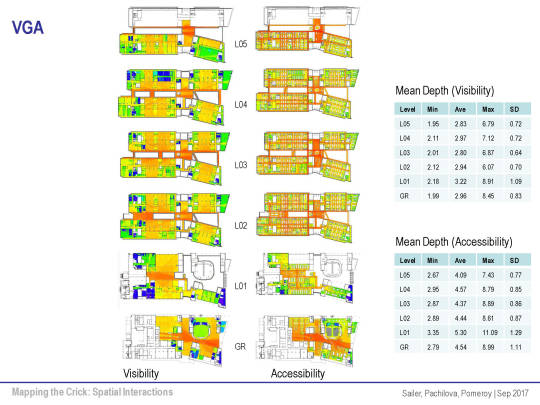

Fig 1. through space syntax analysis, we can see the strong visibility and accessibility in the building. (Salier and Pachilova, 2017)

This can seen through space syntax analysis, which demonstrates the strong visibility and accessibility in the building (Salier and Pachilova, 2017) but wondering around The Crick, it was clear that the ethos of the building was reflected in the lived experience, scientists held meetings in communal areas, there was a general buzz of activity and social events and open invitations were tacked to the wall. The building had a system of feedback, reflection and adaptation and it had a life of its own.

References

Bourdieu, Richard., Pierre Nice, and Nice, Richard. Outline of a Theory of Practice / Pierre Bourdieu ; Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1977. Print. Cambridge Studies in Social Anthropology ; No. 16.

Crick, 2019. Website. https://www.crick.ac.uk/about-us/our-vision

Gibson, James J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception / James J. Gibson. Boston, Mass. ; London: Houghton Mifflin, 1979. Print.

HO+K, 2019. Website quotation. https://www.hok.com/projects/view/the-francis-crick-institute/

Penn, A. 2008-2009. Podcast; Introduction to Adaptive Architecture and Computation – Video – lecture 5 Architecture and Architectural research.

Sailer, Kerstin; Pachilova, Rosica and Pomeroy, Ros (2017), ‘Mapping the Crick: Spatial Interactions’, presented at Workshop ‘Following the life of the Francis Crick Institute’, funded by Wellcome Trust, 4th September, London

0 notes

Text

On the configuration of knowledge: the power of sight

Leadenhall is a building defined by sight-lines and the power that comes from transparency to facilitate knowledge. From conception to construction, the North Core to the open plan floorplate of Rogers Stirk Harbour & Partners, it is a stalwart of modernist configuration and a demonstration of how sight and structure can relate to user.

Open plan, open source, globalisation these all present a contemporary shift in our social consciousness to a more collectivist approach to solve issues; most likely because our accessible networks are now so large and our issues so big that we no longer feel we are uniquely capable of resolving them.

Figure 1- the construction of The City, Tasha Tennant

Leadenhall is situated right in the heart of The City of London, the labyrinth that once existed at street level, guarded by traders, ruled by economic development but still overseen by the church is now usurped by a plethora of high-rise buildings that sit above the London smog, making their own declaration of capitalist power perhaps. Ironically, the rapidly developing urban fabric of The City, which has given rise to buildings such as Leadenhall, is largely an adaptation to the ubiquity of the internet and its decentralising influence. Canary Wharf, we’re looking at you.

Yet, there’s something that persists in the social and structural milieu of The City that still takes precedence over its configuration – St Paul’s Cathedral. The prohibition of any building to inhibit the sight-line of St Paul’s puts a limiting parameter on new architecture but it also speaks to how we value visibility and the traditions who held power and how knowledge was transferred.

As Hillier writes, “The relation between space and social existence does not lie at the level of individual space, or individual activity. It lies in the relations between configurations of people and configurations of space.” (Hillier 1996:31). The social history of The City configured Leadenhall by directing what should and shouldn’t be seen, which gave rise to its wedge - or Cheese grater – appearance. In turn, Leadenhall now returns something back to the social of The City; something visually stimulating, an office space for people to inhabit and new system of knowledge production.

Entering Leadenhall, the escalator you take draws your eye to the entrance, the stilts that hold up the building draw your eyes up, making you aware of its grandeur. You follow your direct line to back of the building, the North Core, sat on the rear façade, it’s easy to navigate because the open plan layout gives you full view of the building. You get to know it intimately because even the components of construction are revealed to you, “We like to expose things, that’s what we do,” remarks Jack who swiftly presses some buttons on what looks like a giant I-pad and leads you to elevator B6 so you can ascend the high-rise.

Figure 2- the elevator in Leadenhall, Tasha Tennant

The elevator is yet another incredible visual stimulator, endless cables draw up further up into the building, and the exposed framework reminds you of the Meccano set you played with as a child.

Entering Rogers, on the 14th floor, the open and transparent sensibility is also played out in the practise. From the exposed ceiling, devoid of panels, to the completely open plan configuration you get a sense that they truly embody their ideology. Even from the entrance you get an excellent visibility across the majority of the office. The open plan allows you to clearly orientate yourself in the space, which in turn provides you with knowledge about what is going on and how people relate to one another; this has the capacity to propagate a collectivist knowledge of the practise as a whole and as the saying goes ‘knowledge is power’.

Figure 3- Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, Tasha Tennant

Space may be strongly or weakly programmed, meaning it has a varying amount of knowledge prescribed to it. Rogers is a weakly programmed office meaning there is;

“More spontaneity in terms of knowledge transferable,”

as said Jack. Though in theory you would agree, walking around the almost silent office, with workers plugged into their own Spotify playlist hidden behind black screen, perhaps this spoke more to knowledge opportunity rather than the lived reality. Although, the fact you made visit at 5pm on a Wednesday may have impacted your evaluation.

“Sight is without doubt our dominant sense, yielding nine-tenths of our knowledge of the external world,” (Pocock, 1980). At the level of the building Leadenhall allows for its users to gather a knowledge of London, its changing city-scape, the business of the street network below, the weather, it gives you get a sense of ‘the world’ beyond work. Within Rogers itself, the weakly programmed spatial structure that holds the visual in the highest regard facilitates a harmonising company environment that allows for a collectivist knowledge to flourish.

Leaving Leadenhall, you look westwards to see St Paul’s before heading back to the tube, each holds power over the other, each are remarkable in terms of aesthetics and each has something different to offer The City and the social network that exists within it.

Figure 4- The View Below, Tasha Tennant

References

Hillier, Bill. Space Is the Machine : A Configurational Theory of Architecture / Bill Hillier. New York ; Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1996. Print. Page 31

Pocock, D. C. D. "Sight and Knowledge." Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 6.4 (1981): 385-93. Web.

0 notes

Text

Who has ownership of space?

You’ll quickly realise that although UCL is big and seems open, there’s a rabbit warren of spaces you can’t squeeze through and you are (even as a graduate student) just the visitor here, your hunch is confirmed as you walk up to a door only to find it shut, a black box to your left, flashes red – you can’t enter. A girl almost half your size it seems, with brunette hair, baggy jeans and an ominously sized tote bag, fearlessly walks up to the door and scans her card; it flashes green and four beeps in a major key signal that she can go through. She walks in with the confidence of a queen who knows this is her land; you’re left outside to press the ‘call’ button and wait for the sympathetic receptionist to ask your name and let you in.

There are inhabitants of a building and there are visitors, but the boundaries between them are not clear; for example, at UCL, the student reside on campus daily, their cards give them access to the majority of the buildings (degree depending) and this is an institution which, at least in theory, is designed for them and their development, so they are inhabitants, right? But if I tell you, the student’s leave after a number of years, they have a fluid ownership limited by time and the educators on the other hand – are here to stay. What then?

Though lecturers are more likely to stick to one building, they are able to penetrate the core of the space, they have offices; they are a permanent fixture, so is this theirs? Then of course you complicate matter further, you have the library staff, the cleaners, those who work in the campus cafés and bars and that binary of inhabitant/visitor no longer seems an adequate way to categorise the social life of a building, you understand that there is a larger social network at play, one that shifts with space and time and where you can assume a number of different roles.

“Well, this is the Slade.

You think you’re coming in?”

At the Slade, you are brutally reminded that this is not your territory. A woman, in her late 50’s, stack of books cradled in one arm turns to you as you try to walk in and scathes, “Well, this is the Slade. You think you’re coming in?”

The Slade has prestige; it considers itself an elitist institution that only loosely sits underneath the umbrella of ‘University College London’. It is a space of tension because in essence it is a private space within a public university. Though we like to think there is a democracy to our education and student status, the Slade requires a membership that you don’t have. The building is understated, sitting on the left flank of the Main Quad, there is no attention-grabbing sign that says ‘here, look at me, I’m the Slade’ no, this is a building that doesn’t want to be disturbed and walking through the silent, high-ceilinged corridors you’d think the same of the students and staff who use it. Amongst the stretch canvas and empty rooms and is that a secret elevator? you get lost, you are not wanted here, you don’t belong.

The Slade is a stark contrast to the Bartlett, a new-built cube that has a weightless feel due to its façade punctuated by large rectangular glass windows, through which you can see models and papers, the life of the architect visible to you from the street level. It invites you in to see more. The door though small, and arguably hidden beneath the cantilever, is flooded with students and staff running in and out, a group of four stand just off to the right, cigarettes in hand, conjecturing with the other, deep in some discussion about their next crit, you’re sure. Your entrance is not an event to them, you are free to enter and explore the ground floor exhibition space.

Similar to the Slade, the Bartlett does require membership. Beyond the initial ground floor space you will find a barrier that requires key card entry but this is set back from the entrance. The inhabitants of the building can go deeper but as the visitor you are encouraged to come in into the foreground of the building and join the social network.

Private spaces have boundaries, they are excluding, this may have negative connotations, but requiring membership to a building can be useful. It creates a social space where inhabitants are intrinsically connected before meeting - the supporting social structure is pre-fabricated though it’s walls and doors are free to transform.

Membership defines more directly the inhabitants and visitors of a building (though there are still levels to ones inhabitation) and gives structure to the social meaning of space. Knowing you have ownership of a private space changes your behaviour, as with the student who swans into the student centre, the artist who tell you this is the Slade, or the architect who smokes on his doorstep. As a visitor you may feel like an outsider or an invited guest but you assume a different social identity to the inhabitants. Even on your journey through UCL’s buildings your value in the social network shifts, you move from one building where you have deep entry, to a democratic space with where ownership is dissolved amongst its current users; to another building where you reach an impasse and cannot join the social structure. The dualistic framework of inhabitant-visitor isn’t sufficient to describe the social life of a building, it cannot help us answer who has ownership.

The social network of its users defines ownership. It’s a fractal network, held equally between the minds of those who encounter it and the physicality of the building itself. You take a left out of the North Cloisters onto the rear corner or the Main Quad, someone catches your eye and you watch them disappear behind a wall and wonder where they went to; and if you’d be allowed in.

2 notes

·

View notes