Text

A girl who's a boy who's a girl: On Femininity

I worry that I'm a closet femme-phobe.

As far back as I can remember, I've felt like I've failed at femininity, and as a result felt deep-seated resentment at being seen as a girl. Even now sometimes, when I'm around feminine people, whether they are cis, trans, or nonbinary, I feel an intense anxiety rise within me. I feel scrutinized and on-edge. I hyper-fixate on my appearance, my body, my skills as a performer, comparing myself to femmes and finding myself sorely lacking. I find myself thinking unkindly about femmes, trying to ascribe flaws to them that don't exist.

Femme-phobia is very common among queer men. George Frederick Leeder describes in his article, "Masculine, independent, and 'not acting'," how the men he studied conceptualized masculinity to be in direct odds with femininity. For these men, a necessary part of what masculinity means is devaluing and rejecting femininity, resisting at all costs the association of queerness with femininity.

I am acutely aware of this. I in no way consider femmes beneath me, and I try to uplift and support the femmes in my life. I am in love with one. But I can't seem to completely shake off the feeling that I find refuge in masculinity because I want distance between myself and femininity, which I feel like I have failed at. I want to be freed from the expectations and standards of femininity, and adopting masculine style gives me space to breathe.

Kelsey Snoot, a Black transmasc writer, and Lisa Fouweather write that we need a new masculinity that is not built upon the degradation and rejection of femininity. As Lisa calls it, an "antithesis to toxic masculinity." Kelsey and Lisa describe a masculinity characterized by emotional intelligence, vulnerability, openness to physical affection with other men, and desire for connection.

I am all for this concept of masculinity. I like that it teaches men to respect women rather than coerce or dominate them, to connect with them instead of being willfully ignorant of their needs and desires. If I'm going to be masculine, I want to be masculine in a way that doesn't essentially position femininity as "other."

And yet, on some deep level, I still can't shake the feeling that I'm a boy using masculinity to keep femininity at arms length.

I think my femme-phobia comes from a different place than it does with cis and queer men. My impulse to reject femininity comes not from male revilement for women, but from AFAB anger. In her essay, "Female Rage Is Here To Stay," Nonkosi Tazibona describes feminine rage as a response to the oppression and violence women have been subjected to. As an AFAB person, I am acutely aware of the subjugation of feminine people, and I am angry. In the words of an anonymous writer, "I may not be a girl, but I carry the anger of all the women who came before me." I want to escape violence and cast off oppressive roles as much as any feminine person does. But Maya Angelou says:

"You should be angry. You must not be bitter. Bitterness is like cancer. It eats upon the host. It doesn't do anything to the object of its displeasure."

And when I feel the impulse to mute hyper-feminine performers on Instagram, when I cringe at girls wearing flimsy pink collars and cat ears, when I resent nonbinary people for successfully performing femininity.... that's bitterness. That's me wanting to cast off society's feminine role for me so badly that I recoil from femininity completely. That's not kind to femmes and not healthy for me.

I could have wallowed in this bitterness forever. But then something amazing happened.

I joined a rock and roll dance troupe.

When I auditioned I was nervous. There were only two men there out of more than two dozen dancers. I was expecting the dances to be split into strictly masculine and feminine movement styles, like all the dance classes I had taken. I was preparing to compare myself to all the feminine dancers and consider myself severely lacking in talent. But I had a blast. The choreography was fast and energetic, with plenty of head whips, hip thrusts, and isolations. Think Cell Block Tango meets Coyote Ugly. Think heavy metal Pussycat Dolls. And everyone was as kind as they were talented. I got cast for the show, and months later I joined the troupe.

Our logo is a middle finger, and appropriately so. We will flip off our audience, twerk in their faces, and kiss each other in our opening act. If we're not dancing to classic rock, we're dancing to anthems of female strength and rage.

And the thing is, even though all of my troupe-mates are femme-presenting, I feel more empowered than I ever have been performing with them. I feel no discomfort with their femininity, in fact I slot in right alongside them. Their femininity and my masculinity complement each other perfectly. When people misgender me when I'm in their company, it stings and it's annoying, but it doesn't send me into a gender dysphoric spiral.

What our troupe reminds me most of is bands of the early 90s Riot Grrrl movement, spearheaded in part by the all-female punk rock Bikini Kill. Riot Grrrls were female musicians who aimed to bring awareness to feminist issues framed through the lens of punk rock. In addition to denouncing misogyny in the music industry, they fought against capitalism, commercialism, mainstream beauty standards, and oppressive gender roles. Their fuck-you attitude was encapsulated in both their music and their clothes. When one of the singers from Bikini Kill was on stage, she would often wear nothing but a bra top, with "Slut" written on her torso. She'd fit right in in my dance troupe.

All this to say, on stage with them, I feel in touch with a femininity in defiance of misogyny that empowers me and brings me joy. It is a femininity that encapsulates an anger without bitterness. A creative punk rock anger, inspiring me to take up space and speak my truth in defiance of all who seek to stifle me. And as an enby, I feel an intense relief that a femininity exists that I'm not seeking refuge from or defining my own masculinity in opposition to. Finally, femininity can co-exist with masculinity in me, without antagonism or contradiction.

"Masculine, independent, and 'not acting': Hegemonic masculinity and femmephobia within an online community of queer men," by George Frederick Leeder

"Soft Masculinity: The Antithesis To Toxic Masculinity," by Lisa Fouweather, published on Portfolio of Hope

"The Potential of (new) Masculinity: Finding Belonging in a Soft-Boi Era," by Kelsey L. Smoot, published in Medium, October 9, 2023.

Iconoclast: Dave Chappelle + Maya Angelou

"The Riot Grrrl Style Revolution," by Laura Havlin, published in AnOther, February 4, 2016.

"Female Rage is Here to Stay," by Nonkosi Tazibona, published in The Weird Brown Girl, July 26, 2024.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The End of the World, and the Beginning: On t4t Love

On the surface, my girlfriend and I couldn't be more different.

She is a self-identified clown, an exuberant performer with hair the color of cotton candy. When we go out dancing, she shakes her ass all night and kisses more girls than she can remember. I dress all in black and own an unreasonable number of Demonias, and at the club my resting bitch face is second to none. She listens to slut-pop, I listen to boys who look like they have consumption wail. She makes friends with ease and has partners all over the country. I am slow to warm and so far, she's the only girl for me.

We are inversions of each other. And I mean that as a play on words. In math, "inverse" means opposite in position, direction, or effect. In sexology, "sexual inversion" was a theory popular in the late 19th and 20th centuries positing that homosexuality results from an inborn reversal of gender traits. She and I have opposite effects, reversed traits.

But one thing we have in common is that we're both trans. Our relationship is trans4trans, or t4t.

The term t4t arose from early 2000s Craigslist personals as a way to segregate trans people from the categories of "m" and "w" and help trans people hook up. But the term has evolved beyond simply describing trans-trans pairings to encompass a whole philosophy of trans people relating to each other, strategies for making those relationships visible in a transphobic world, forms of art and erotica, and practices for creating networks of mutual aid and support. T4t goes beyond categorizing a partnership. It opens up an entire world of trans experience.

It opened up my world. Before being with her, I had only every been with cishet men (I am not counting one tragically closeted bisexual). While they all supported my gender identity, I always felt there was a limit to how well they could understand me. I felt a lack that I didn't realize existed before I was intimate with another trans person. How thrilling it was to be with her, the way she desired me the way I ached to be desired. How fulfilling, the way she recognized the challenges and triumphs of being trans in the world. How affirming, the way we looked out for each other, deeply cognizant of each other's triggers and highly attuned to each other's emotions.

It sounds like paradise. My elation at being with another trans person is echoed throughout countless blog posts, essays, and zines about the joy of t4t love. These stories are inspiring, and crucial in today's world that seems hell-bent on dehumanizing and erasing trans people.

But I confess, stories like that don't capture the full picture of what being with a trans girl is like for me. To explain what I mean, you have to understand: I fell in love with her before she transitioned. I fell for her the moment I saw her. She was dancing, manipulating her body in ways that made my heart pound in my chest. She had thick dark hair, eyes like jade, an easy smile, and a lithe toned body that I envied and lusted after in equal measure. And I could see a sadness behind her eyes that made me ache with desire.

The first four years we were together, we struggled to grow close. We texted each other almost every day, but barely saw each other. The first time we kissed I froze from anxiety, she had a panic attack and took kissing off the table for a while. We'd make plans, she'd cancel. We desired each other intensely and tried having sex multiple times, but neither of us could relax and she'd end up leaving in the middle of the night.

All that changed when, after much conversation on the matter, she decided that she wasn't a man. I supported this wholeheartedly, since I could tell she was unhappy. What I didn't understand clearly at the time was how much change lay ahead and the wild journey we were about to undergo together.

In the years since, she's undergone two pronoun-changes, HRT, and three surgeries. And being by her side through it all, I've come to understand something about t4t intimacy that I never imagined, which is that love between two trans people is as much about death as it is about creation.

Let me explain.

Like most great works of art, the movie I Saw the TV Glow invites many different interpretations. The film is about two high schoolers who are introduced to a mysterious TV show about two psychically linked girls fighting supernatural foes that eventually blurs into and subsumes their reality. The characters realize that they truly are the two psychically connected friends in the TV show who have been trapped underground, left to die. One, a transmasc character played by a transmasc actor, chooses to return to the TV show by burying themself alive and reemerging as their true self. The other, who has the body of a boy but who is truly a girl, chooses to stay in the "real world" and slowly die underground. At it's core it is about coming out as trans. But to me, the movie is about the specter of death in the trans experience and the horrifying possibility of rebirth.

The first time I watched this movie with my girlfriend, she started sobbing 10 minutes in. And no matter how many times I see it, I can't stop myself from crying either. The idea of death of self as the price of realizing who you truly are hits both of us hard. The movie uses liminal imagery to convey the terror of living suspended between different states of being, that can only be ended by dying and coming out the other side. In coming out as trans, there is the suffocating fear that you could annihilate who you are, with only the slightest promise of what you could be to guide you. I think my girlfriend believes that in order to live truthfully, she had to destroy the part of herself that told a lie. When I described my love for this movie to her, she wrote to me:

"You wrote about love being destructive, I find that poignant and devastatingly accurate. Loving you and being loved by you in a way that I deem appropriate has forced me to confront the lies I told myself to continue existing inauthentically. I don't fear the destruction love has wrought."

She's not the only one who considers destruction to be necessary for love. Growing up queer, in a string of bad relationships with cishet men, I internalized a lot of trauma surrounding bringing my full self to intimate relationships. Cameron Awkward-Rich and Mil Malatino describe this in their essay, "Meanwhile, t4t":

"The more structurally disenfranchised, maligned, and abandoned the we is, the more angst, trauma, mistrust, and fear of abandonment we bring to t4t relationships."

They state that resolving this trauma and creating something better involves destruction, which might bring relief, pleasure, productive conflict, and a sense of being seen, if only partially. They write:

"T4t can offer so much: some measure of respite, a break from cis-centric optics and assumptions, a relation through which we might learn more about what we want to become, what we desire, how we want to live in these so often fraught body-minds, mutually actualizing touch, a little room to breath just a bit easier, perhaps. But it is also a crucible through which we come to learn just how opaque we remain to each other, just how intensively we've internalized the lessons taught by trans antagonism, just how difficult it is to see, love, want, fuck, support, and simply be with each other. Whether these tough recognitions are failures or lessons, though, depends on what we (fraught, imperfect, ongoing) do next?"

So what was I going to do next? I made, I continue to make, the decision to destroy the self-doubt, mistrust, jealousy, and fear that prevented me from loving and being loved by the person who mattered most to me in the world.

Dying and coming out the other side isn't easy. It takes time and patience, for both of us. I've learned, through being by her side going through the terrifying act of perpetual rebirth together, that t4t love is infinitely mutable and non-linear. As Torrey Peters writes in Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones:

"T4t is an ideal, I guess, and we fall short of it most of the time. But that's better than before. All it took was the end of the world to make that happen."

"Meanwhile, t4t," by Cameron Awkward-Rich and Hil Malatino

Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, by Torrey Peters

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good luck!: On Comp Het

The first time I heard "Good Luck, Babe!" by Chappell Roan, I was sobbing by the first chorus. And every time it plays, a shiver goes through me and my sight blurs with tears.

It might seem strange, that a song written by a lesbian about her closeted lover hits me so hard. Though I am, blissfully, in a relationship with a girl, she is my first girlfriend and I do not identify as a lesbian. Before I dated her, I had only ever been with cishet men.

With one exception. And it's thoughts of him that flood my mind by the first three lines of Chappell's song.

I had a lover of five years, who I'll call R. I was 15 when we met, he was a year younger. Our circle of friends barely intersected, so we were only passing acquaintances until we were housed in the same dormitory in college. I was surprised at how glad I was at the prospect of seeing him daily, even more so by how much I looked forward to running into him in the stairwell after dorm meetings, where I'd drag out conversations with him as long as I could. He was studying classical literature and philosophy, spoke Latin fluently, and had a natural aptitude for math. He had sable hair and eyes the color of withered leaves in autumn. Within a few months I knew I wanted to sleep with him. It wasn't long until I got what I wanted. The morning after he knocked on my door, and he didn't go back to his room for the rest of the school year.

It sounds romantic. It was. I was the happiest I had ever been. But we agreed that it wouldn't last. He intended to transfer the next year. I had a boyfriend back home and he wanted a monogamous relationship with kids. So the last night we spent together we promised each other it was over.

But it wasn't. We couldn't keep away from each other. For the next five years I'd make my way to the city where he lived. Every time we'd promise it would be the last. And every time it wasn't. He dated people, I dated people, it didn't matter. We couldn't quit each other.

But something changed in him. When he used to be so passionate about his interests and intellectually curious, he became detached and somber. I attributed it to the pressure of school, to the kind of girls he was dating, to his drinking. And I'm sure that was partly true. But I started to notice how he'd act around his best friend. He became particularly animated around him. He'd joke about us all having a threesome. He looked at him with an expression that was very familiar to me.

Long story short, I came to realize that I was sleeping with a bisexual in absurd denial of his true self.

How did this even happen?

Many AFAB lesbians, as they venture out of the closet, come across the term, "compulsory heterosexuality," or "comp het." The term was coined by Adrienne Rich in her essay, "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Experience," published in 1980. Rich, who identified as a political lesbian, came out late in life after having children and becoming widowed. In a nutshell, compulsory heterosexuality describes the way that AFAB people are socialized into assuming that they are heterosexual because they are never made aware of alternative options. Society teaches them that the very idea of being a woman is inextricably linked with being heterosexual. So they unquestioningly enter heterosexual relationships, where they submit to the subjugation that a male-dominated society places upon them, and ignore or resist intimate relationships with women. As Rich puts it:

"Women learn to accept the inevitability of this 'drive' because they receive it as dogma."

She states that compulsory heterosexuality is enacted by men exercising power over women, by commanding and exploiting their labor, stifling their creativity, withholding education and culture, denying their sexuality, and forcing sexuality upon them. She also explores the intersection of compulsory heterosexuality with capitalism, in that women are indoctrinated into heterosexuality because of their economic disenfranchisement at the hands of men. She writes about how women participate in their own subjugation by identifying with male values and points of view, which perceive women as lesser.

I was aware of the idea of compulsory heterosexuality, as I am an AFAB queer person who has spent most of their life in relationships with cishet men. But faced with a closeted AMAB lover, I found my understanding glaringly limited because of how much Rich's concept of the term centers on the lesbian experience. In her essay, Rich was concerned about two things: one, how and why women's choice to be intimate with other women has been "crushed, invalidated, forced into hiding and disguise;" and two, how erasing the existence of lesbians theoretically and politically holds back feminism.

I was faced with the question: what does compulsory heterosexuality look like for AMABs? Society does not perpetrate subjugation of men at the hands of women. Women generally do not have power over men. So how are AMABs socialized to assume that they are straight, pressured to have straight relationships, and taught to reject same-sex intimacy? And how can they free themselves?

I don't know the answer to this question. I have my own ideas. I could try to psychoanalyze R. Was it because of his Latine culture's emphasis on a kind of masculinity that demands heterosexuality? Was it because he internalized our society's homophobic lesson that happy and stable same-sex relationships aren't possible? Was it because he hated his father? None of those answers satisfy me.

But I do know how compulsory heterosexuality hurts you. Rich did too. She describes:

"The doublethink many women engage in and from which no woman is permanently and utterly free... indoctrination in male credibility and status can still create synapses of thought, denials of feeling, wishful thinking, a profound sexual and intellectual confusion."

I could see clearly all of those effects on him, in the jokes, the regretted hook-ups, the drinking, the serial cheating. I remember one afternoon in Paris, we were chain-smoking on the balcony of a beautiful flat his girlfriend's parents owned, and between the second and third cigarette he turns to me and says:

"Sometimes I dream about sucking cock."

What could I say? I say,

"I know, babe."

Yeah, good luck with that.

R and I don't talk anymore. Last I heard he converted to Catholicism, changed his name, became a lawyer, and got engaged to a girl he met at his parish.

It is sad to me that we could have supported each other, each grappling with comp het in our own ways. We could have been a good match, with me being both a girl and a boy, depending on how you look at it. But how could I expect him to shake off comp het feelings when we know so little about how queer men are hurting, let alone how they can heal? I don't have any answers.

But I wish him all the best in the world.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saying "Yes": On Style

"I would prefer not to." - Herman Melville, "Bartleby, the Schrivner"

I love queer nightlife.

I love the eclectic creativity on display. I love the acts of radical love and sexuality. I love the passion and talent of the performers. I love the culture of consent. They are a welcome respite from the oppressive expectations and insidious, compounding violences of the world. It is a thrill to witness the innovative ways that the freaks and outcasts shake off the roles and the shame society shackles them with. I nod my head reading Travis Alabanza describe their reverence for clubs in their book, "None of the Above":

"Through my experience of club culture, I was able to create alternative associations with parts of myself that the outside world had tampered with. I could go from the minority to the majority using just a sweaty hand stamp, passing through a half-broken basement door."

Alabanza describes her love for a phrase often used in queer entertainment: "Ladies, gentlemen, and those lucky enough to transcend gender!" She writes that people like me are lucky for deciding that we exist outside male and female roles. We choose something different, and in doing so manage to become ourselves.

But I struggle at times to understand what the different thing I'm choosing even is. So often I feel as though being queer is a long series of Nos - to certain ways to dress, to dance, to look. This feeling does not always go away in queer spaces. Queer people love to play with masculinity and femininity, neither of which hold any interest to me. In sideshow in particular there is notable gendered distinction, not in identity (many sideshow performers identify outside the binary), but in presentation. Femininity is performed especially often, to the extent that I find myself believing that to be talented in my skills is to be skillfully feminine.

My identity feels like a string of negatives. Alabanza would consider this a positive: "How lucky I felt to be illegible." They're not the only queer writer to tie queerness to negativity. In his book, "No Future," Lee Edelman suggests that if society is going to tie queerness with negative qualities like shame, deviance, selfishness, and self-destruction, we should embrace it. We should accept and celebrate our opposition to oppressive heteronormative and capitalistic values like productivity, reproduction, and consumption. We should fight against what Lauren Berlant calls "cruel optimism," the irrational belief that enduring ways of life that hurt us will eventually pay off and make us happy. Queer negativity offers, as Mari Ruti writes in her book, "The Ethics of Opting Out":

"An antidote to the valorization of success, achievement, performance, and self-actualization."

I find this a worthy goal. However, Edelman loses me as he goes even further to proclaim that this negativity opposes every form of social viability:

"The embrace of queer negativity can have no justification if justification requires it to reinforce some positive social value."

In other words, there can be no social creativity in queer negativity. Ruti refers to this position as "antirelational" thinking, and criticizes it as a theory put forward by white gay men who don't comprehend that the position that we can and should exist outside of society and revel in negativity demonstrates privilege that marginalized people, who are "already leading overly precarious lives," don't have. She critiques that valorizing queer negativity results in giving up political will and power, which many cannot afford to do.

So can queer negativity be creative? Ruti thinks so:

"If Edelman reads negativity as a matter of self-annihilation, I read it as the foundation of many of the things that make our lives worthwhile: our psychic complexity; our capacity to be interested in the surrounding world; our desire to interact with others; and our tendency to form meaningful bonds with those we love."

To understand how, we need to talk about Judith Butler and Jacque Lacan.

Judith Butler is an American philosopher and gender theorist who identifies as a lesbian, is legally non-binary and uses they/them pronouns. They are known for their theory of gender performativity, which is, in a nutshell, the idea that we create the illusion of a stable gender in ourselves by repeatedly performing elaborate acts that mark us socially as a "woman" or "man." Furthermore, they state that our gender identities are formed through social action in a relationship with power, specifically, a collaborative relationship. Everything we do, even attempts we make to resist power, requires a dialogue with it. We cannot exist outside of a relationship with power, no matter how hard we try.

Jacques Lacan was a French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist who posited that we form an identity when we become unconsciously aware that there is a chasm between how we perceive ourselves and how we wish we were seen by others. Sounds familiar to me, is this not the experience of so many trans and nonbinary people? Put another way, Lacan would say we are defined by "lack." How we understand ourselves as subjects is an illusion created by internalizing "signifiers," which are given meaning by "the Symbolic," which is defined by "the Other" - parts of the world that are outside our conscious control. As far as gender is concerned, he believed that "male" and "female" are given meaning by "the Symbolic."

But Lacan also believed in something called "the Real" - a state of being beyond culture and language, beyond "the Symbolic." This is where he and Butler part ways. As Ruti puts it:

"Butler has insisted that because every part of the subject has been infiltrated by power, the real cannot be anything but a symbolic construct; for Butler the very notion that there could be a kernel of being that resists the symbolic is itself symbolically produced - one ideological fantasy among others. The Lacanian perspective is merely that such shaping has never been entirely successful."

Simply put, Lacan believes there is something deep within us that exists outside of how power shapes us, how "the Symbolic" defines us. To access that, we harness what Ruti calls, "the negativity of freedom": essentially, the power of saying No. To quote Ruti again:

"The negativity of freedom - the No! - is crystallized in the so-called Lacanian "act": a destructive act through which the subject, momentarily at least, extricates itself from the demands of the big Other by plunging into... the real. In other words, even when we feel overwhelmed by the webs of power that surround us, we possess a degree of autonomy as long as we are willing to surrender our symbolic supports, as long as we are willing - even temporarily - to genuinely not give a damn about what is (socially) expected of us. Insofar as the subject occupies a place of lack in the Other (symbolic order), we can perform separation and suspend the reign of the big Other."

Ruti posits that it is here that negativity possesses the power to create social relationships, not sever ties. The Lacanian subject separates itself from the Other to become closer to someone(s) who they value so deeply that they are willing to risk being incomprehensible in order to be truly themselves. Ruti writes that in doing so:

"We gain the ability to wield the signifier even in highly rewarding ways. We gain the capacity to be interested in the world around us, we gain the ability to desire, and sometimes even love, others."

If I accept Lacan's belief that there is a part of me that exists apart from "the Symbolic" and determines who I truly am, Lacan would consider it my ethical responsibility to remain true to this part of myself. But I return to my question of who am I, gender-wise, in society if I have separated myself from roles and expectations, from "the Other"? As Ruti asks:

"If social subjectivity is a function of being interpolated into the symbolic order, then how can we even begin to conceptualize forms of desire that have not been completely overrun by the desire of the Other?"

Lacan believes that each of us relates to this "lack" in an entirely unique way. But I sometimes struggle to transform my own feelings of "lack" into a coherent gender identity. Instead of saying No!, what do I want to say Yes! to? Ruti, again, has an answer for me:

"If the process of fashioning a singular place within the world results in a distinctive subjective "style," this style always expresses something about the manner in which the symbolic and real, however tenuously, come together and amalgamate."

Style.

I've found that's my answer. I've come to prefer style to gender. Style is mutable, individual, infinitely creative, DIY. Style crosses gender lines. I see Alexander McQueen, visual kei, emo boys, yami kawaii, goth, punk and I think Yes! Yes! Yes!

Friedrich Nietzsche says it better than I can, in "The Gay Science":

"To give style to one's character - that is a grand and rare art! He who surveys all that his nature presents in its strength and in its weakness, and then fashions it into an ingenious plan, until everything appears artistic and rational, and even the weaknesses enchant the eye."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is this man bothering you?: On Visibility

It happens every night after a show.

My fellow dancers and I at a bar decked out in leather and fishnets, cooling off with drinks as sweat evaporates off our bodies after an hour-long show. My troupe-mates' hair is down, their long lashes barely clinging on after 60 minutes of head-banging, their tits and asses barely - but strategically - covered by layers of bodysuits. Every night after a show is the same: as we cluster around the bar, a guy approaches and pushes between us, yelling something we can barely hear over the band. And I see it immediately on my friend's face: a stiff smile hiding barely restrained rage. She's the baddest bitch I know, more than able to take care of herself. But I see behind her eyes deep exhaustion. So that smile is my signal.

When I insert myself between him and my friend, and make an obvious effort to ignore him, he'll spend a few minutes mumbling and try to reposition himself until he realizes I'm not moving. Then he'll move on. My friend's smile will turn genuine, and we'll finish our drinks in peace.

If cishet men must see me, that is how I want to be seen. In general, I prefer to be invisible to people socially. Much has been said about the invisibility of transmasc people: the erasure of their experiences from political discourse, from media, from medicine; the belittlement of their perspectives in queer spaces where they are perceived as privileged gender traitors. I agree that it is imperative that I be visible to politicians and doctors. I too ache to see people like me on screens and in books.

But if I am not on stage, where I have full control of how I am seen, I am pretty uncaring about whether I am seen or not. Perhaps that is part of the agender experience. If I relate to neither male or female or masc or femme social roles, if I recoil from having such expectations placed upon me, how do I make myself comfortably visible? If the price of social visibility is the obligation to adopt a character that is entirely wrong for me, do I welcome invisibility?

When I don't know how to answer such questions, I read. And I came across S. Bear Bergman's book, "Butch Is A Noun." This book is a gorgeous exploration of butch-ness, which is "a gender all its own, something which cannot always be described within the confines of the bigendered pronoun system we have now." And these words jumped out at me:

"Butches are monosyllabic, until you get to know them, which they will not allow but want, or will allow and want, or will allow but don't want, or won't allow and don't want, so you may or may not get to know them, but you should try, or not."

How well that sentence captures the ambivalence and indifference I feel about being perceived, the indecision and frustration I feel about being seen. And ultimately, the directive that you should try, or not, to know me, that I don't care either way.

When I insert myself between men and my friends, I am casting off invisibility and assuming some gendered role. But what role feels correct? Bergman offers further insight. His book has an entire chapter dedicated to the butch's essential role as a safeguard for femmes:

"When I am walking with a pretty girl, or sometimes a femme boy, things change; my gender changes. The girl, as they say, is mine, and my gender performance has to change in order to meet that expectation. I have seen all manner of men and boys melt away when I appear and rest my hand lightly but familiarly on a waist or neck, looking friendly and interested but present and big in my body. It rises up in me unbidden, every time, the knowledge that keeping this femme safe when I am not present may have something to do with the public perception of who might be in the wings to protect her."

In the book, "Persistence: All Ways Butch and Femme," Karleen Pendleton Jimenez writes in her essay, "A Beautiful Creature":

"My definition of butch involves chivalry. I want to be courageous, gallant, to show the highest respect for a woman."

She tells a story of when she was nine years old, when a girl at camp asks her to hold her when she was scared by the counsellors' gruesome stories. She describes the elation and pride she felt protecting her: "Everything, for an instant and for the first time in my life, felt right."

These descriptions of "butch," as an identity onto itself, resonate strongly with me as I consider where my social instincts lead me. I know that I may never be seen as butch... I don't have the stereotypical body or aesthetics. But Bergman and Jimenez's words offer an alternative gendered role that I can fulfill at least in my own mind. A way to be visible, at least to myself.

And it's worth it to protect my friends. As Bergman states:

"I do it to give something back to these femmes who take such good care of me, in so many ways, in whatever small way I can."

Butch Is A Noun, by S. Bear Bergman

Persistence: All Ways Butch and Femme, edited by Ivan E. Coyote and Zena Sharman

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nikita Gill, from Your Heart is the Sea: Poems; "The Scars You Left on my Mind Want a Talk With You," originally published in 2018

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Nikolay Punin, from a diary entry featured in The Diaries of Nikolay Punin: 1904 - 1953

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

whoa. kitty cat blep // piece done for starrysnepfox!

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

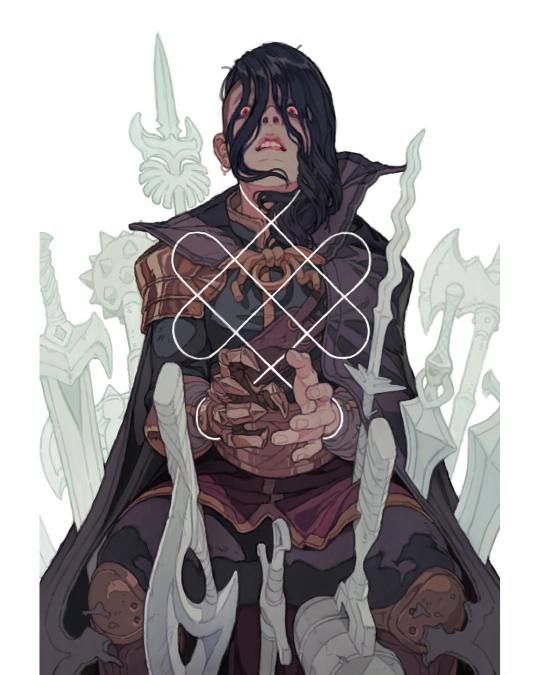

back with the left handed drawing cuz my dominant one is dead as hell, as per usual

somft thanzag…

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

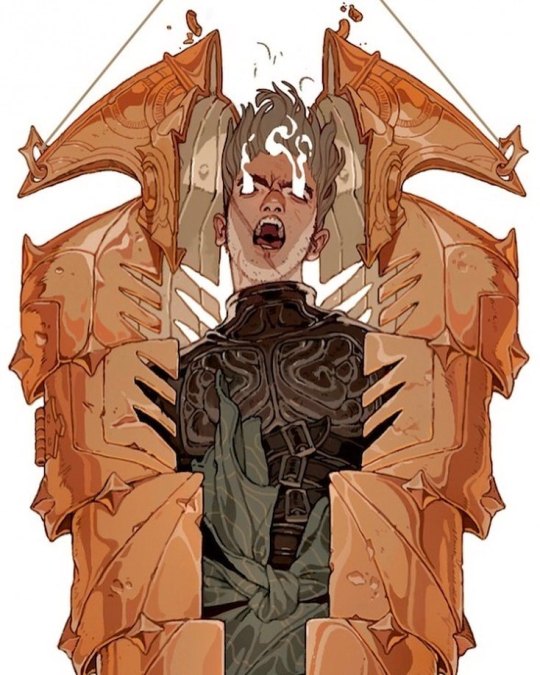

It's inktober time of year again! Going to be animating every day for the 4th year in a row. ✨

Day 01: Dream

26K notes

·

View notes