Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

Did he enjoy the works of Avram Davidson and the works of Charles Williams?

Hi—I don't think he has much on the record for either. Williams's biggest books might have hit during the years when Lafferty was mostly reading nonfiction, but certainly he doesn't interact with his work to the extent he did Tolkien (negatively) or even Lewis or David Lindsay. His relations with Davidson were mostly in the latter's role as F&SF editor. Again, I suspect he read him, since Davidson was a pretty big name at a time (late 50s/early 60s) that Ray was reading *everything* in the field. Very possible I'm forgetting something, I'll update if I find it as I go back over the correspondence.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lafferty in Debonair

Finally managed to dig up a Lafferty publication that, while hardly secret (it’s been listed in the admirable if incomplete list over at Galactic Central) nonetheless has not to my knowledge been documented online yet. It’s not in any of the institutional holdings I’m familiar with, and comes up so rarely for sale that prices seem more like random stabs in the dark—either far too high (maybe? who knows?), or suspiciously low.

It’s also quite possible—likely, even—that Lafferty himself had no idea it had been published. More on that in a sec, but first:

If I hadn’t already assured you there was a Lafferty story here, you might think this image unrelated. It’s the first issue of a publication called Debonair, which by 1964 was very late to the Playboy clone market. Still, the cover promises the standard blend: pieces on the bachelor lifestyle, travel, sex, and the arts, alongside erotic photography that reads now as touchingly chaste. The literature seems to be here mostly on the rationale that the Playboy model includes fiction, so we should have it too, though short of the international prestige (and very high rates) promised by a platform like Playboy and the marketing machine of Hugh Hefner, it was never going to be a major selling point, nor was Lafferty’s name going to move any copies off the newsstand. (The other short stories in the issue are by the prodigiously productive Henry Slesar, and by Van D’Amato, most likely an editorial pseudonym since that name is uncredited anywhere else.)

The Stanley in “Stanley Publications” here is Stanley P. Morse, and his involvement, however tangential, provides a major clue about a magazine about which very little documentation exists. Morse came to prominence as a prolific if not highly-regarded publisher of comics, especially of the weird/horror variety; as Lawrence Watt-Evans sums him up:

Anyone who thought men like Bill Gaines gave comics a bad reputation had never met Stanley Morse. Naturally, he published horror comics, including some of the grossest and most vile. … I don't think Morse was trying to imitate E.C.; I think he was trying to top them. Not in quality -- that would never even have occurred to a man like Morse. No, he was trying to outdo them in gore, violence, and shock value.

After the Wertham Panic, Morse didn’t even try to stick with comics, jumping ship instead to men’s magazines in a variety of formats: war yarns, adventure tales, survival fiction, and quite a lot of stories about women being tortured or otherwise placed in peril, all wrapped in covers that were lurid even by pulp standards. (If you’ve read this far, I urge you to pick up David M. Earle’s book All Man!). Debonair would’ve thus have been a paint-by-numbers attempt to reach an audience that considered itself slightly more refined: lose the blood and sadism, add some arts and culture, above all else keep the boobs.

It may seem strange for Lafferty, a Catholic conservative, to appear or seek to publish alongside such fare, but he was hardly prudish on these matters, or at least not so prudish that he would pass on a paying market at a time when he was struggling to place much outside his SF/F strongholds. Certainly he had tried to query Playboy as early as January 1959, sending them an early version of “Adam Had Three Brothers”; he sent them almost a story a month for the next year and a half, of which “One at a Time” was the last. (It would eventually take Kidd’s influence to land him that Playboy spot in 1972 for “Rangle Dang Kaloof,” a story that, whatever its other charms, would not likely be anyone’s recommendation for a Lafferty intro.)

“One at a Time,” on the other hand, is a fantastic choice for introducing someone to Lafferty. The author himself seemed pretty enamored of it, even if it couldn’t quite seem to find the right category for it. He tried most of the science fiction and fantasy press, he tried lit mags like New Mexico Quarterly, prestige outlets like Harper’s and The New Yorker, and men’s mags of varying respectabilities, from Rogue to Nugget to Sir Knight. (Especially intriguing: he notes that he “incorporated it into a short novel” in September 1960 before rewriting it again as a short story two years later; I haven’t yet found any trace of this novel otherwise, but the prospect of a Galveston-centered novel is tantalizing.)

What remains uncertain is how “One at a Time” got into Debonair. Lafferty was fastidious about recording his submissions, and it is clear from them that he did not submit to Debonair directly, or to any Stanley Morse-run periodical. He also does not record any payment received from the magazine, or from its parent company. There is no correspondence between him and any of the above. There is no contributor’s copy in his personal archive. In the years after, he does not even seem to be aware that the story was ever published, since he sends it to Fred Pohl in 1965, and then—after a final rewrite—to Damon Knight, who finally takes it for Orbit in 1967 or ’68. When he lists his publications prior to signing on with Virginia Kidd, it’s Orbit that he lists for “One at a Time.”

It would not be at all uncommon for an outfit like Stanley Publications to move a story submitted to another one of its magazines to a new one it was looking to fill up—Morse is particularly difficult to track in this respect, because (Watt-Evans again):

[Morse’s] titles often changed publisher from one issue to the next as he dodged creditors or changed partners, and would sometimes have cover art taken from a story in a different issue as deadlines were missed. If he came up a story short he would simply reprint something. If he couldn't get an artist for a particular slot, he'd have his editor cut up and rearrange the art from an old story to make a new one.

One could easily see Morse, or one of his interchangeable editors, grabbing something off the slush pile to fill out a new magazine, something that didn’t quite fit the all-action mags but definitely is a tale of a bachelor lifestyle. And as one can verify from the first paragraph alone, alongside the manuscripts in the archive, this is clearly an earlier, if not much different, version of the story later published in Orbit and in Nine Hundred Grandmothers.

And yet. The story has these striking, specially commissioned illustrations, one depicting McSkee asleep, and another four of the five things he indulges in while awake (singing being the part of the “pentastomic orgy” left out). The artist signs himself as Donald Leake, a well-known industry illustrator of the period with a number of books and album covers to his name—not someone you’d tend to get at the last minute. Additionally, the magazine is undeniably of a higher quality than the more customary Stanley Publications content—full color ink on a glossy cover, spot color on the illustration, more expensive paper throughout—though it does also have the usual apparatus of the pulp world, the ads in particular…

Chances are that, unless further documentary information turns up, this is a mystery that will not be resolved. If I had to make a guess, it would be that the story got mishandled or misfiled by someone at the literary agency where Lafferty had sent the story, possibly for a consultant’s reading—there is a listing among the submissions above that the story went out twice to (presumably Theron) Raines and did not come back the second time. If someone there got wires crossed and sent it on to Debonair thinking that it came from a client, it’s further possible that the payment would’ve been delayed, mishandled, or otherwise unprocessed, and thus word of its publication never reached the author. Whether that proves true, or whether the truth is even determinable, remains to be seen; in the meantime, enjoy this bit of Laffertiana not quite like any other.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

85. Among the Hairy Earthmen

A mescalanza is, in Spanish, a “medley” or a “potpourri” or a “miscellany.” In Italian (as mescolanza), it’s any sort of mixture, often a mix of people or of ideas. Either way, it’s a collection of disparate elements that combine to form something greater than the individual parts could ever have been alone; often, the combination brings out aspects in the originals that no one could have predicted.

The earliest extant drafts of “Among the Hairy Earthmen”—which for a good while went by the name “The Long Afternoon,” though others were considered—imply that the story was developed as just such a mescolanza, in much the same way as the later “Nor Limestone Islands” would be a lapidary work, or the later still “In Deepest Glass” would be a cathedral window. (Or further, in the way that almost every Lafferty work contains some sort of image of its own processes of inscription.)

Certainly this draft seems to be the first short story that really piled on the epigraphs—a fixture of Lafferty’s novel writing from the first, and very present just then from his work on Archipelago, but which he had been more reticent to deploy in shorter stories. What’s more, it may well be the first mention of “The Back Door of History,” that compendium of shadow historiography that provides excerpts for many a Lafferty tale—and it’s the author of this work who introduces the word mescolanza, though in this early stage the pseudonymous author is listed as Arpad Dotch, not Arutinov. The narrator of the story cites four epigraphs in all, alternating Lafferty inventions from “The Lighter Side of Geology”—by one A.E.C. Copps, who does not recur—and “The Back Door of History” with two actual quotations from John Addington Symonds’ magisterial history The Italian Renaissance and Frederick Rolfe / Baron Corvo’s History of the Borgias. (These two British eccentrics were quite different in most ways save one: they were both about as openly queer as it was possible to be in the societies of their time.)

There’s indications that a Chesterton quote may also have been part of the miscellany—something I think he would appreciate—but none of these quotes made it to the final draft; they were all removed amid extensive rewrites trying to get the story to the point that Fred Pohl would buy it. In a letter from February 1964—after Lafferty had already rewritten the story multiple times, including earlier in the month—Pohl notes that “you have something interesting, entertaining and stimulating to say, but because you say it in a jackdaw’s-nest of unrelated bits of scenes and snippets of history you make it hard to read. … my quarrel with THE LONG AFTERNOON is that it is an easy story which you have written in a hard way.” It would seem that the number of quotations has only grown since the first draft, and Pohl admits himself bewildered: “But do you really need the quotations? From the first you only take the words ‘from Byzantium’; and take them only to deny them—but you have thrown twenty-odd data at the reader; since he does not know which are important, he tries to hold them all in his head, and when he finds out that by-God none of them are, he grows to dislike your story.”

Pohl made a further suggestion—“Suppose you rewrite the story, without quotes, in some consecutive form—perhaps as a narration”—which Lafferty carried out, which is why we have the story in the form we do. The “easy story” Pohl wanted to highlight is still complicated, a synthesis of readings across a huge number of historical subjects in the 13th to 15th centuries, but at root it is a story of alien visitation, of the subvariety where the aliens accelerate human development at a particular place in time; Lafferty’s innovation is to place this in medieval Europe rather than in Pharaonic Egypt or Attic Greece or for that matter the future. The story zeroes quickly in on the children at their arrival and follows their activities over the two-hundred-odd years which saw the Renaissance kindle and burst into life, up until they leave on the heels of a disciplinary thrashing from a mysterious human pilgrim. There still isn’t really a plot, but there is a “continuity” to proceedings—or enough to satisfy Pohl, at least. And some parts of it are vastly improved between the first draft and published versions.

And yet I still wonder about the version that could have been: the hard-way story, the jackdaw’s nest, the mescolanza. It would’ve been yet another work of Lafferty’s that embodied the formal experimentation of the New Wave, years before editors like Moorcock and Knight and Carr and Goldsmith—and Pohl himself!—commissioned and championed them. What “The Long Afternoon” lacked in continuity, it could have made up in innovation, inviting the reader into a wholly different role than just the receptor of a narrative: by throwing all these selections at the reader, making them distinguish between the real ones and the invented ones (see, always see, Don Webb on this technique), Lafferty press-gangs his audience, turning them all into fellow researchers, sifting through textual evidence. And if the reader ends up uncertain which data are or aren’t important, or uncertain of the entire enterprise generally, then Lafferty has already succeeded by muddying the epistemological waters sufficiently that the “aliens spearheaded the Renaissance” theory no longer seems fanciful—or, at least, no more fanciful than the idea that humans just up and did all those things on their own.

It’s not as if “Among the Hairy Earthmen” is a bad story. There’s a lot to investigate within it, and quite a few interesting questions to ask—maybe if I can ever get an actual medievalist to read the tale, I can get more and better answers than my own scanty reading on that period allows, but at the very least: What do we make of the story’s implication that humanity may be better off without such periods of frantic activity? (Note the ultimate sterility of the rapid society in “Slow Tuesday Night”; though also contrast the rich fecundity of the sped-up science types in “Brain Fever Season.”) Who is that final Pilgrim, and how did he come to the knowledge of the children’s interventions? Are those same children, as implied, back for another long afternoon; and if so, what dubious gifts are they giving us now? And yet, it’s undeniable that the effect of such questions is different when they are handed directly to you by the narration, rather than when they emerge from your navigation of Lafferty’s peculiar bricolage. (On this, see Gregorio Montejo, in Feast of Laughter 4).

The archive does not record whether Lafferty genuinely thought the story better in Pohl’s preferred format, or if he just went along with it because it was the only way it was likely to see print. If the latter, then it doesn’t seem to have affected his other stories much; the following years would see Lafferty send out many more formal experiments, including “What’s the Name of That Town” and “Primary Education of the Camiroi,” both composed during these same months that he was rewriting “Among the Hairy Earthmen” (and both, moreover, bought by Pohl). But I have to wonder if the ordeal didn’t at least color his view of Pohl, perhaps even mark an early stage of the process whereby the editor who, in Lafferty’s own words, “picked me up out of the scrap pile” became the editor who “was never right, but sometimes he was pretty insistent.”

Completed December 1961. Rewritten March 1963, December 1963, January 1964, and twice in February 1964. Published in Galaxy, ed. Frederik Pohl, August 1966. Collected in Ringing Changes. New York: Ace Books, 1984.

Next entry: "Crocodile," a dystopian tale about printing that had to go to press twice because they forgot a page

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

84. Seven Story Dream

One of Lafferty’s better-known mystery stories, thanks to its inclusion in Does Anyone Else Have Something Further to Add?—actually, the only one of his mysteries to feature in any of his major-press collections. It’s a mordant tale of striking confidence; one can see why a platform as big as Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine went for it. And yet, without the efforts of Virginia Kidd, it probably would’ve been just another unpublished manuscript in the Lafferty archives.

Lafferty submitted the story to A.L. Fierst soon after writing it, in November 1961; the agent apparently didn’t reject it, as he did many of Ray’s SF stories, but he did not succeed in selling it—and likely did not try to. Unlike several other of the mystery stories which Fierst failed to sell, such as “Enfants Terribles” or “Almost Perfect,” Lafferty did not continue to shop this one on his own; instead, it would sit in his file boxes for almost a decade, when Virginia Kidd asked him which of his older stories might be worth a look.

It might not be quite the coup of “Enfants Terribles,” which Kidd succeeded in selling to the undisputed top-tier mystery mag, Ellery Queen’s, despite Lafferty trying that same market and many others years before, but landing an abandoned story in the market’s #2 magazine is no mean feat. Hitchcock Mystery had started back in the ’50s, piggybacking on the success of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV anthology series. The magazine kept their namesake’s famous silhouette and predilection for suspenseful tales, but otherwise operated completely independently—although on occasion the show would adapt stories from the print outlet; it’s sort of a shame that Presents was no longer running when Lafferty’s story did, as it would have made a fine episode.

Kidd’s other intervention with the story was a little more understated. It wasn’t her practice (with Lafferty, anyway, or with any of her other clients I’ve researched) to make changes directly to manuscripts; instead she would make the case that the material needed changes, and leave the author to provide them, or not. But in this one case, Kidd—who, though best known for her efforts representing SF/F writers, had a fondness for mysteries and a very keen eye for plotting and characterization—did the touch-up work herself, and only then mailed Lafferty for his approval. Sadly, the letter in which she initially proposed the change seems to have been lost (as opposed to the one where she acknowledged his acceptance), but we can recover the shifts by comparing his manuscript draft with the version as published:

Manuscript: The machine played now in the compelling voice of Gilford Gadberry, as it had often played to George Handle in his sleep till he had learned it: “I killed Minnie Jo Merry. I killed Minnie Jo Merry. Strangled her and threw her out the window. I killed—”

Published story: The machine played now in the compelling voice of Gilford Gadberry, as it had night after night played to George Handle, in his sleep, till he had learned to answer on cue; and the cue, of course, was the question: “Who killed Minnie Jo Merry?” “Pretty uninspired,” Gadberry had to admit, “but I had to assume uninspired questioners, to whom the cliché would come naturally.”

(As a side note here, what is Lafferty playing at by calling a character George Handle? I can’t find any connection to the composer, but it tantalizes nonetheless.)

There’s actually quite a few red herrings in the story, not so much at the basic level of whodunit—the identity of the real killer is never in any serious doubt—as it is about why he did it, and how he set up someone else to take the fall. As ever with Lafferty, these elements reflect on the meta level of the story’s composition.

Much of the story seems to revolve around sleep-learning, or hypnopedia. To educate himself, Handle listens to recordings, some of which he paid Gadberry to make, while he sleeps; Gadberry takes the opportunity to have Handle hypnotize himself into admitting he was the killer. In pondering where Lafferty would’ve encountered this practice, we could turn to his self-education in science fiction, where it’s been a favorite trope since Hugo Gernsback himself put it into Ralph 124C41+, and Aldous Huxley put it at the heart of his Brave New World. But there’s a more immediate reason it might’ve been on Lafferty’s mind on or just before November 25, 1961, the day he finished the story: on November 16, an episode of popular sitcom My Three Sons revolved around sleep-learning—in this case, learning Spanish, which lifelong language-learner Lafferty might’ve taken particular interest in. Furthermore, the plot of the show involves the recordings being changed out surreptitiously, though for the purpose of a moral to be learned, rather than a murder to be covered up.

In the show they use a home record player; I went down a rabbit-hole trying to figure out exactly what sort of audio equipment Lafferty would’ve had in mind here; thanks to his engineering training and his job selling electronics parts, he was fascinated by consumer electronics and media technology generally, but he’s maddeningly imprecise in his descriptions here, with mention made of “the tapes, the wires, the records” crowding Handle’s apartment. In 1973, when the story was published, it clearly would’ve been standard-issue cassette tapes, which had been available for a decade. But in 1961, when he was writing this, cassette systems were much larger, and the bulk as well as the cost scared many consumers away from getting what seemed then like a novelty.

Ultimately it doesn’t much matter (he said, setting aside huge amounts of media theory dealing with modernism, hypnotism, sound reproduction, and death)—what matters is that the murder itself is getting displaced by a question of technology. As we discover, the reason for that murder is primarily aesthetic: the murdered woman was more aesthetically pleasing dead than alive. But this is the basis for essentially every murder mystery, nearly all of which require at least one corpse to fulfill their own aesthetic—something which Northrop Frye identified in assigning the genre not to the realm of moralism or any romantic restoration of society, but to the realm of sadism and ironic comedy. The exact identity of the character who made the corpse is ultimately irrelevant; it might be the person repeating “I killed Minnie Jo Merry. I killed Minnie Jo Merry…” or they might be ventriloquizing those words at the impetus of another, but in the end it’s the author who’s responsible: theirs is the aesthetic judgment that necessitated the killing. In making a mostly aesthetic decision to carry out a murder, Gadberry reflects also on the morality of the author as artist, even to the point of staging the opening scene for maximum sensory effect (in the process “savagely striking down” a lone white flower—again, subtlety not really the point of this piece). He cites as his motives “jealousy, frustration, curiosity,” but the first two are clearly deprecated to the third, which he shares with any author who creates a character for the sole purpose of killing them off.

This is a grim promontory on which to find oneself, philosophically speaking, and I wonder if it isn’t that which led Lafferty to shelve the tale for so long. There’s a further inquiry to be had over the degree to which this tale deviates from the spirit of oft-cited inspiration G.K. Chesterton, whose Father Brown treats murder less as a crime against morality than as one against rationality: there is evil in the world, and no amount of detection will make that wholly right again, but so long as such crimes can be made comprehensible within the wider moral universe then the logical coherence of that universe remains unshaken. By contrast, Lafferty’s Gadberry acts according to his own morality, in which the aesthetic is prime above all—a true Decadent.

Curiously, it’s Kidd’s edit that steers things back toward a more Chestertonian morality, by bringing in the notion of the cliché. In the original version of the ending, Gadberry’s deception is solely for the purpose of maximizing the aesthetic purity of his world, in which murdering a woman and framing another man is perfectly justifiable in the quest for artistic experience. The idea, however, that he is phrasing his hypnotic direction in such a way that it would be triggered by “uninspired questioners” shows that he is aware of the competing moral framework; moreover, that he is perfectly willing to betray his own artistic vision when doing so more effectively panders to the anaesthetic or the artless, thus undercutting any claim his competing moral universe might have to internal coherency. By pulling the story back from the madness of decadence, Kidd made it into a serviceable detective tale—one that critiques the genre and its clichés, without consigning the whole thing to oblivion on the basis of a single core flaw.

Completed November 1961. Published in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, ed. Ernest M. Hutter, July 1973. Collected in Does Anyone Else Have Something Further to Add?, New York: Scribners, 1974.

Next entry: three centuries of history in a single afternoon, in “Among the Hairy Earthmen”

0 notes

Text

83. Once on Aranea

An impostor tale, in more ways than one. It’s one of Lafferty’s more straightforward science fictional space exploration tales—which is to say, not straightforward in the least, but at least trying harder to uphold the premise than “Snuffles” or “Ride a Tin Can.”

This is particularly true of the earliest version of the story, written in October 1961 and revised shortly thereafter at the direction of his agent, A.L. Fierst, whose specialty (to the debatable extent that he had one) was stories that hewed very close to genre standards. Many of these early stories, in fact—and especially a lot of the unpublished ones—were written on assignment from Fierst’s correspondence-course fiction class, as exercises in writing to a particular genre and market. His views of science fiction, in particular, were stuck firmly in the Golden Age glory days; the fact that he even bothered to send notes on “Once on Aranea” rather than returning it outright would seem to indicate that Lafferty was closer to the norm here than usual—and perhaps that this story represents him consciously trying to write to the form, rather than satirizing or burlesquing it, or transforming it utterly.

Even so, he can’t help making it a tale of metamorphosis, and not just for main character Scarble. One by one the men of the unit are left to scope out an alien planet and its lifeforms all by themselves; one by one they come back having experienced some sort of shattering experience—if they come back at all. It’s a process that extends likewise to the reader: exposure to the stuff of science fiction is dangerous, and it provokes changes in those who experience it, often for the worse.

The first version of the story, the Fierst version, ends at the point where Scarble is undergoing his change; the action remains firmly “on Aranea” with further outcome uncertain; perhaps this inconclusiveness is why neither of his early champions, Fred Pohl or Doc Lowndes, bought it. There’s a few other differences; in particular, Lafferty tips the surprise a little early by noting of the two-legged adolescent spiders that, due to their birth cauls, “sometimes it looks as though they arrive with space helmets”—but then, subtlety was never the story’s strong point. But much of the remaining framework was already in place: in particular, the beginnings of the Habitable or Hundred Worlds setting that will reach its fullness in works like Annals of Klepsis and Sindbad: The 13th Voyage, as well as the rush of religious imagery accompanying Scarble’s messianic metamorphosis, including the spiders singing choruses both of Hallelujah and Resurrection—Anastasis, even, a loaded word even by Lafferty standards—as well as Scarble eating of “the putrified mass” of his dog: an ersatz Eucharist.

(One rather less churchy aspect did get cut substantially: Scarble’s improvised ballad about dating a twelve-legged spider. See more below.)

Lafferty wouldn’t return to the story until 1965, when he substantially revised it in the middle of a big spree of rewrites, aiming to get some of his early unsold stories out the door. By this point, he was well-established as a science fiction writer, part of Pohl’s Galaxy-If-Worlds of Tomorrow stable. But it was Lowndes who ultimately bought the story—or, at least, reserved it; Lowndes’ magazines always operated on shoestring budgets, one step ahead of the creditors. This time, the creditors caught up, and the story reverted to Lafferty, where it would remain until folded into Strange Doings as the collection’s one previously unpublished tale.

The lengthy coda that Lafferty added to this story raises the stakes considerably. Now all the foregoing is just prelude to Scarble’s return to earth, where he acts as host for a vast spidery invasion force. What once was a simple if religiously charged alien metamorphosis now becomes a grand imposture: most obviously in the form of Scarble himself, now no longer human but rather “Emperor of the Dodecapod Spiders of Aranea, Prefect Extraordinary to the Aranea Spiders of the Dispersal, [and] Proconsul to the Spiders of Earth,” but also in its approach to science fiction. Before, the reader fed on the putrescence of science fiction only on the far-off planets that were its stock in trade. Now, that same reader is liable to take the infestation back into everyday earthly life, and to infect other peoples, or genres, with millions or billions of little ideas.

But in yet another guise, “Once on Aranea” is Lafferty celebrating the dispersal of his own ideas. In this reading, Lafferty is himself the spiders, luring in science fiction (or at least its agents, in the form of editors) to view his handiwork, and gently but firmly inducing them to metamorphose, before using them to infect the rest of humanity by propagating his works through their platforms. Where once he struggled to attract their attention, now he has several of them eager to spread his submissions—and, by the time Strange Doings came out, he was one of the most in-demand authors in the entire field. Sadly, it wouldn’t last much past that. But while it did, it was well worth a Hallelujah chorus, spider-sung or not.

* * *

Scarble’s Song

In the revised manuscript and the published version, only one verse of Scarble’s ballad is given, as below:

“The Spaceman frolicked with his girl Though all his friends could not abide her. She was a pippin and a pearl, She was a comely twelve-legged spider.”

Since this clearly is his intent, it would be appropriately left out in any subsequently published version. However, in the earlier draft version, the ballad continues a bit longer, and it seems a shame not to at least note it in passing:

Scarble sang badly, but he sang loud. That’s the main thing.

“He sat upon her twelve-kneed lap And wished that it was even wider. Let all be silent who, mayhap, Have never loved a living spider.”

The spiders gave him the background beat with their chirping. His audience loved him, and there were millions of them.

“He’d glad explore her every side, He’d get upon her back and rider her. Amazing notion to bestride A real dodeca-gated spider.”

Say, that Scarble could sing when he let himself go! He was one singing man!

“Embracing her below, above, It seemed that he was quite insider her. None knows topography of love Who never loved a twelve-armed spider.”

Then there were some rather vulgar verses treating the idea of the topography of love and the mechanics of the thing in these unusual circumstances; and it ended with a ringing—

“With paler loves be they content Who never had the love of Spider.”

* * *

Completed October 1961. Rewritten in December 1961, January 1965, and February 1966. Published and collected in Strange Doings, New York: Scribner’s, 1972.

Next entry: Another of Lafferty’s idiosyncratic mysteries, “Seven Story Dream”

1 note

·

View note

Text

82. All But the Words

Ray Lafferty was a man of few words. Ask anyone who knew him, or even just anyone who ran into him at a convention: he hardly ever spoke, and when he did, it was in a voice so soft that even microphones couldn’t pick him up and people had to lean into hear him. But while he didn’t have much to say—except from behind his typewriter, at least—he sure did like to listen to others, and that gets reflected in one of the lights and most effervescent apocalypses he ever put to paper.

Just as “Through Other Eyes” hinged on a time machine and “Bubbles When They Burst” on instantaneous communication, “All But the Words” is an Institute of Impure Science story that hinges on an old science-fictional chestnut—in this case, a universal translator—being made to work, but not the way one might expect.

Obviously Lafferty the lifelong language-learner would have an interest in translation devices that “could now interpret roughly the thought processes of earthworms and ferns and even crystals. They could record and even verbalize the apprehensions of metals under stress and, to an extent, the group consciousness of gathering thunderheads. Any language, terrestrial or distant, could be given a cogent interpretation.” But the inspiration here seems to be less about mutual understanding, and more about sociability: after all, the alien society of which Albert-Tentative is part seemed to understand enough about humanity to dismiss from their transmissions of it as “sick,” until Energine Eimer came along to chat with them.

I could go off on a theory tangent here on Hans-Georg Gadamer (a Laffertian name in real life!), and his theories about how communication is only possible when there is some sort of shared horizon between the communicator and the communicatee—that is, there can be no real understanding until there is some sort of mutual agreement that there has been an attempt at communication. Or I could hop back on the Lafferty metafiction route and speculate about how Smirnov and the other Institute folks taking a step back from the attempted communication in favor of someone who “actually likes people” might be a mild rebuke of a science fiction field where many of the practitioners too easily barricaded themselves away from anything like “everyday people,” and who, as Smirnov has it are “mostly talking to ourselves, even when we’re nominally talking to others.” Or, as one further gambit, I might wonder if Lafferty’s inspiration for this story came from Project Ozma, which attempted to monitor interstellar radio waves in a search for extraterrestrial intelligence—that started up just the year before this story was written, and it got written up in Time among other places, so you’d expect an electrical engineer and hobbyist like Lafferty would take an interest.

But that all seems perhaps a bit beyond for what Lafferty called, in a letter to Virginia Kidd, a “nothing story,” maybe based on it sitting around for a decade or so. For her part, though, Kidd rebutted, saying maybe like Albert-Tentative itself it’s not much in size, but “what charisma, what eloquence!” She also noted that then-Galaxy editor Ejler Jakobssen sat and read the story in the parking lot of his post office and had basically decided to buy it within ten minutes of getting his mail. And I sort of think they’re both right: “All But the Words” is basically by design not the deepest lafferty, and it’s not one that sticks in people’s heads like some others. But it is a lot of fun, and that more than anything else was what Ray was aiming for in his stories, particularly during these early years.

Next entry: off to the spider planet, with “Once on Aranea”

Completed October 1961. Published in Galaxy, ed. Ejler Jakobsson, July-August 1971. Collected in Strange Doings, New York: Scribner’s, 1972.

1 note

·

View note

Text

81.5 Dotty

A few closing thoughts that I couldn’t quite fit in—there’s an awful lot to this book, and I wish more people got the chance to read it!

• While Dotty is generally considered an Argo novel, one of the more interesting connections is to his unpublished and much-requested novel Esteban, a historical novel tracking the life and travels of the African slave who was the first “white” (i.e., non-Native) man to enter much of what would become the southwestern United States. I’ll cover that novel soon enough, but suffice here to say that Lafferty has Dotty follow Esteban’s trail much as he himself did, speculating about his path and crisscrossing over top of it multiple times; it even occupies a particular part of her grief, as she had daydreamed about following the trail with Charles and their offspring.

• As ever with Lafferty’s works that veer into cultural criticism, there are some moments of ungraciousness, even a viciousness out of step with the compassion and capaciousness of the rest of the book. Dotty has some of Lafferty’s most harrowing pictures of alcoholism, and of a culture organized around the sustenance of alcoholics; it also speculates about “the trade” of prostitution, and how many of the women connected to the Wooden Ship in one way or another practiced it at some point. But the current and former alcoholics, and the former (and in a few cases relapsing) prostitutes all find a place in Lafferty’s society; they all have something to contribute. Compare that against this diatribe linking homosexuals and users of drugs other than alcohol to sadists, child molesters, slave owners, racists, and murderers:

Filth is the only diversion worthwhile. What is deceit without truth? What is treason without allegiance? What is to be said against the queers and hop-heads — can they be judged without a standard? By what right is the sadist denied satisfaction? Or the child molester his joy? Who shall abridge the freedom to own slaves? Why deny the racist the right to rule? What is subversion if we are all born subverted? What is murder but the action of matter on matter? What Heaven will avenge the killing of the unborn, since Heaven ended yesterday?

Now, it is always dicey to link an author and their characters—though Lafferty does the same here in some ways, attributing materialist philosophies to Balzac and Joyce, among others, on the basis of their written fictions—and one could certainly make a case for these as the thoughts of a despairing, heartbroken teenager, rather than of the middle-aged electrical salesman who wrote her. But they’re of a piece with his commentary elsewhere, and this uncharitable tendency doesn’t exactly get better with time.

• In connection with this, there is something off-putting about Dotty, an Irish-American Catholic girl, referring repeatedly to the God whom she regards as forsaking her as “the Old Jew,” most especially when speaking about Him in her fury and grief as “a debt-caller who has to be paid with the last drop of blood.” In 1990, readers were far removed from the anti-Semitic Church Militant preaching of Father Coughlin, but in the early 1960s—while still far off his 1930s peak—he was still serving as a parish priest, and his radio show would still have been in the living memory of many Catholics. I would balance this carefully against the other treatments of Jewish individuals in his works, and remind again that these are not the words of the author, but of the character he created, who goes on to issue a mental apology to “all the good Jews” (as opposed to the “bad” ones that God is acting like?). Something to bear in mind.

• There’s a great deal here, as in many of his books, about secular materialism, mostly here though as philosophy rather than organized political force. As usual, it is the only other coherent worldview Lafferty acknowledges (here, anyway, we’ll get to the others in time): either there is God, in which case there is the Church; or there is no God, in which case there is the Party. When Dotty first loses the Faith, she careens toward its antithesis with a speed that one almost might call “dialectic,” were synthesis between the two truly possible. I even wonder if the “plus one” of the book—at least, the aspect of it that appears as the permanent suspension of the third act—is not a structural attempt to forestall such a synthesis, to forbid it from taking place. Certainly there have been attempts to join Catholicism with Marxism, such as in liberation theology, but Lafferty would recognize them only as a uselessly watered-down version of both.

• Finally: the special edition of Dotty released by United Mythologies Press includes the otherwise uncollected (pre-Centipede) story “Holy Woman.” It’s an inspired pairing, not least because the women at the core of each story are so different, but also because both works took about 30 years to break into print.

Next entry: back to short stories after years away, with “All But the Words”

0 notes

Text

81.4 Dotty

Time heals all wounds. That is a proverb, an untrue proverb. There are wounds unhealed by time enough to fill every lazare from the beginning. All time can do is to give a little time, to achieve composure, to make a mask. You build it out of textured wax, and if you are skillful it looks just like your face, just like your face will look ten years from now. But it doesn't fit right. You never saw one that fit right.

There’s a lot of heartbreak here, and I’m going to try to cushion it with analysis. I won’t succeed, but at least I’ll have tried. It was Sheryl Smith, as far as I know, who first noted in her essay on Arrive at Easterwine the three-plus-one pattern that Lafferty often uses to structure his plots (check it out in volume 4 of Feast of Laughter). I’ve written a bit about this “plus one” in other contexts, as have others. But once you start reading with it in mind, it’s something that turns up all over his short fiction; Dotty and Archipelago stand as proof that he was experimenting with it in his early novels as well—and crucially also that this supplement is connected to the Faith and to the operations of salvation.

In Archipelago, the Dirty Five are given as a unit, and yet each of them serves at some point as the plus-one to the rest. Stein, meanwhile, serves as plus-one to the entire group, except for the duration where he is in and Casey is out. Dotty, meanwhile, has three crisis moments attached to three households and three states of her soul, with a plus-one hanging onto each at the end:

First, her mother’s household, which she leaves in dramatic fashion after her mother has already been passed on to The Colonel, her father’s commanding officer. (Oddly, the Colonel proves himself to be a character not entirely unsympathetic, even if in the fulness of time the odds are stacked against his salvation). Dotty does not abandon her faith here, but it’s a close-run thing, and she seeks absolution only in the most grudging of spirits.

Second, her temporary household, the Parisis, which she abandons, along with her faith and her standing in Grace, after her fling with Joe Smith. Thanks to Charles Peisson, this will prove to be a little pitfall, but it feels at the time like a great abyss.

Third, the house she fits and inhabits with Charles, which after his death (and the prior death of their unborn child) she is left to occupy alone, with only the year’s worth of unopened letters he has written from beyond the grave to stand in for his actual person. Whereas the earlier crises reach some sort of resolution, this latter one ends (in the novel, anyway) unresolved: Dotty tries to leave God, to be free of her “Father Complex,” but God won’t give up on her or His own “Daughter Complex”; he uses what Dotty calls “little tricks” to pull her back to the Faith, one friend, one act of care, one Mass at a time.

And this points to the implied “plus-one,” the fourth household or at least community that Dotty has assembled around herself: that of the Wooden Ship pub, and of the broader Galveston culture in which she circulates. The ideal evening for her now is not the fiery benders of her mid-teens, but rather “sit[ting] in her kitchen with thirty or forty friends, and fir[ing] up the old coffee-maker that used to be in a ship's galley. It makes good coffee, and they lace it with brandy or whisky, according to their taste, and talk all night. There aren't a dozen kitchens in that part of town that abound with such salty talk.” Though tentatively back in the faith, she is far from saved—and though the odds may tilt slightly in her favor, it will nonetheless go down to the wire: as Darrell Schweitzer has pointed out, at the end of the novel the state of her soul swings in the balance from one sentence to the next, almost in the gaps between words, each one of them a potentially vast pit sundering her permanently from Charles and the rest of the Blessed.

She is also still, it must be emphasized, very young! Having just “reached her majority” at novel’s end, which by Texas law would have meant turning 18 years of age, 18 years into which she has packed several lives’ worth of incident and grief and loss—see, here’s the analytical blanket failing me. She has lost not just a husband, but a genuinely good partner and friend; she has lost her child; she has lost the future that those lives represented; and she has perhaps lost the Faith that is the only explicatory framework apart from sheer material chaos within which such losses can be made to fit, even if they never quite fit right. Though she will pop up in the background of a couple more stories (most notably “One at a Time”), she is done as a protagonist or even major presence in Lafferty’s world; the drama of the rest of her life will be private and personal. That is, Dotty is now herself a “plus-one” to the Galveston stories, and to the wider Lafferty cosmos: a gatherer of community; a conduit, perhaps, for Grace. So also Dotty itself as a book, particularly as the fourth novel of the Argo trilogy, is a “plus-one” in the Lafferty bibliography: generally one of the last that people pick up, both because of its unavailability, and its divergence from the genres most people generally associate with his work—and yet greatly rewarding to those who seek it out.

I’ll have one more post on Dotty, just some odds and ends I couldn’t quite fit in elsewhere, and then back to short stories at long last.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

81.3 Dotty

Lafferty writes often and at length on the concept of the “world,” by which he means a way of ordering things. Over the course of the 1960s and ’70s, he would write with increasing urgency of how the world was breaking down, how it had disappeared, how it stood in need in replacement. Much of his fiction takes place within the process either of un-worlding or re-worlding; amid the destruction of what has gone before or the construction of what might yet be. Less commonly, he writes from the world as it was, or as he regarded it to have been; usually these are his historical fictions, excepting The Fall of Rome, in which a world does end, but it is not the one of present concern. Dotty, however, reads also like a dispatch from a world gone by; unlike In a Green Tree, the unmaking of the world writ large never really comes into view, though Dotty’s own world will end and renew several times; unlike Archipelago, there isn’t much of an inkling that such a thing could be on the horizon. Dotty does work at the Wooden Ship, and that is used as a parallel for the Argo and thus the Church elsewhere, but that’s less in view here than almost anywhere else in this vein of Lafferty’s fiction.

Still, one remark from Archipelago is apposite: “we are the last young people who will ever believe that the Church is perfect.” That word “perfect” is worth dwelling on; it’s one of Lafferty’s favorites, a word he returns to over and over again. Steeped as he was in the language of Scripture and Catholic theology, Lafferty’s association of “perfect” here would not have been eternal incorruptibility, which is attainable only in heaven, but rather the more mundane and achievable sense of fulfillment, when nothing about the purpose of a thing is in any way lacking. In the world gone by (at least as Lafferty portrays it), the Church had just such a purpose; in the world that is to come—if indeed any world is to come—he anticipates that the Church will seem incomplete, lacking, even purposeless.

All this as background to the use of the word in Dotty, where it appears some 24 times by my count, with nine of them clustered tightly in chapter 15. I’ll get to that novem momentarily, but first some highlights from the other uses:

It appears first in chapter 2, among a description of why the young Dotty is not a tomboy: “She didn’t throw like a boy, though she threw perfectly”—Dotty is a fascinating figure to run a gender analysis on, especially given her enthusiastic stabbing of her macho stepfather, but I’ll spare you all that for now

Next in chapter 4, one of my favorite quotes from the book, during Dotty’s first fateful trip to Galveston: “Dotty enjoyed the dawn, for she already knew a secret that many people never learn: that the dawn isn't miraculous when you get up to see it. It is the crown of a perfect night and it is only a miracle when you stay up to see it.”

Several times she makes a bargain with God to be “perfect” so long as He protects her loved ones—a one-sided bargain, necessarily, but nonetheless one she will have occasion to accuse him of violating

It is quoted in an excerpt from “The Dark Night of the Soul” of St. John of the Cross

Dotty’s mother uses the word three times in a letter, and much like her understanding of the Church and of life, her usage is clearly shown as defective

Dotty uses it to describe both her own logic and the logic of an atheist interlocutor; given the starting principles of a wholly material world or a material world interpenetrated with the immaterial, their two philosophical positions are the only sound results (the narration also uses the word in a similar sense chapters later, after Dotty’s fall from grace).

Now then. It is that fall from grace—Dotty’s seduction of? by? itinerant painter Joe Smith and subsequent abandonment by? of? him—that forms the spine of this book.

(A side note: the narrative voice hardly condemns Joe; for all that he is a sort of ersatz Finnegan, there is enough ambiguity about his motivations that he could read borderline sympathetically. However, from the contemporary view at least: Dotty is a minor and Joe is at least a decade her senior, and his flirtation with her earlier in the book when she’s even younger are easily recognizable as grooming.)

In one sense, it’s sheer narrative necessity that Dotty fall; without the sin, where is the interest in the salvation? And in another sense it’s necessary as an outgrowth of Dotty’s character: as one who is continually shown playing with the proverbial fire, she must also be shown getting burned. But I don’t think Lafferty’s interest here is as severely moralistic as all that. For one, Dotty is very bad at living immorally; after a few hookups she settles down to corrupting herself in a more thoroughly Laffertian way—that is, philosophically. The roll call of names is an interesting one, but suffice for here to say that nothing during this period is “perfect.”

What changes things? The arrival of one Charles Peisson, sailor and Frenchman. Both these descriptors are important: the Frenchness because he has had much experience banishing atheist canards (and these spoken by much more able interlocutors than the coffee shop crew that has helped lead Dotty astray); the seamanship because for all the groundedness of his philosophy, there is a freedom and buoyancy to him that can only come from living mostly off dry land. His courtship with Dotty is brief and idiosyncratic. Their marriage, however, is perfect—emphatically so, as 8 of the 9 uses of the word in the chapter, and a full third of them in the book as a whole, come in a burst at the start of chapter 15, expanding on the concept in that context:

Perfection is nearly always impossible, but it is never difficult. Which is to say that if there is any difficulty to it, any lack of ease, then it has already failed of perfection. All perfect things are easy. But they are not frequent.

The married life of Charles Peisson and Dotty was perfect. From the moment that Charles returned to town, everything was perfect. The mark of perfection is its very simplicity. Charles had a knack for untying knots, for resolving difficulties. The knack does not consist of ignoring the difficulties nor in skirting them. It doesn't even consist of facing them and conquering them in the old copy-book fashion, though apparently they are faced and conquered in another fashion. Or some of them are never conquered at all. Part of the idea is just not to be difficult about difficulties.

If the rest of the idea were understood, then everyone would have perfection; and they do not.

Dotty has by this point purchased and refitted a house; she has also, in clear parallel, refitted herself. She also attempts to restore her bargain with God—and, for a time at least, perhaps the only time in her allotted span of years, her domestic life is perfect and easy, allowing both for boisterous honeymoon hijinks and a peaceful span of a few months before the bargain is tested. (An interesting side comparison would be placing Dotty’s marriage alongside either of her mother’s, whether the legitimate and abusive, or the illegitimate and narcotized; Dotty will be reduced neither to a Tennessee Williams character nor a Joan Didion one.) Naturally, both for general narrative reasons and for specific Laffertian plot mechanics that I’ll get into in my final post on the book, this situation is unsustainable—and perhaps much the same could be said about the Church. But while it lasts, nothing is difficult about the difficulties. It is perfect, and it would be oafish to leave things any other way.

0 notes

Text

81.2 Dotty

Dotty is, in form, a spiritual biography; unlike Lafferty’s first novel of a few decades earlier, however, Dotty’s is not the life of a saint, unless it be an ambiguous one. The course of the novel will see her through advanced juvenile delinquency, multiple family-forsaking crises, several relationships, and state-shifts between grace and perdition so rapid it’ll make your head spin.

All of which by way of saying that Dotty’s spiritual biography is not Ray Lafferty’s. Unlike Archipelago (or the later In a Green Tree books), where Lafferty is drawing on his own life and serves as sort of a present absence throughout, Dotty details a life that is pointedly not his own. Lafferty was never delinquent, never in crisis (at least never to the point of separating the family), never in a relationship, and if he ever felt himself to be out of grace, he never speculated upon it and was never more than a few hours from his next mass, besides.

In the first entry on Dotty, I noted that, as a character, Dotty is not larger than life. But the sheer expansiveness of Lafferty’s conception of life and its size should be taken into account: while there is nothing world-historical about her, nonetheless she is exceedingly precocious, possibly the archetype of all Lafferty’s precocities, model for everyone from Carnadine Thompson in “The Transcendent Tigers” and Clarissa Willoughby in “The Seven-Day Terror” to the entire Rampart and Dulanty clans in “Narrow Valley” and Reefs of Earth, respectively.

But Dotty has neither the joyous household of the Thompsons or Willoughbys, or the sibling solidarity of the Ramparts or Dulantys (or perhaps, for that matter, the Laffertys). Her precocity, in particular her intelligence and her intemperate eagerness to speak her mind (not to mention her predilection for shocking actions), marks her for nothing but trouble. Thus a pattern is set early on: Dotty finds a haven of sorts against the tempests of life, and then catastrophic tempests make that haven unlivable, regardless.

Given this, it’s appropriate that she makes her lifelong home in Galveston, Texas, of all American towns perhaps the most subject to tempest and catastrophe. Lafferty always held Galveston in a special regard; it was the second city of his childhood, one that his family visited multiple times on their summer automotive vacations. Young Raphael would have been far too shy to get up to the shenanigans that Dotty does here (a kiddie version of McSkee’s bacchanal in “One at a Time,” in which an adult Dotty has a cameo), but he shared with her the love for the salt and spray, the “Sea and Island” that serve as “one of life’s spices,” so long as you discover it before nine years of age.

I cannot tell if all their trips were by car or if the Laffertys, like the O’Tooles, ever took the bus. If so, Lafferty would have treasured the time spent listening to others’ stories, perhaps especially those from the Black riders forced to ride in the back. Dotty is one of the few places where Lafferty openly references the segregation he would have grown up within; in Tulsa society Irish Catholics wouldn’t have counted as fully white, especially to the very active Klan contingent that ran Tulsa for several years. But the fully white people of Tulsa wouldn’t have kicked him to the back of a trolley car, and they wouldn’t have burned down his neighborhood, either.

It’s a measure of their comparative comfort that the O’Toole’s have a refuge waiting for them, even amidst the Dust Bowl and Depression. The “farm” on Elm Road is a miniature Eden, an extrapolated version of the Laffertys’ own house on Quincy Road, which was perpetually playing host to various relatives of the greatly extended family. This plenitude is mirrored in what will become Dotty’s second haven, the Galveston grocery store of the Parisis, gathering spot for that island’s Italian immigrant community. But both these havens are acknowledge as temporary respites at best, however utopian they may seem for short periods of time. There is a “curious worsening in the country” at the time, one that infects personal as well as community relations; Dotty will quickly reach a point where she can’t go “home” because that concept no longer exists for her. She will have to build her own home (not just physically, from the studs, but conceptually, from the roots of what “home” means), and constitute what family she can, along the way.

0 notes

Text

Dotty 81.0

Here’s a precursor post without a proper place, so I’ll tuck it in here.

Below are four versions of the introductory paragraph of Dotty. Here’s the text as it would eventually be published:

On a day when Pius X was Pope in Rome and Roosevelt II was president in Washington, when Murray I was governor in Oklahoma City and Slywood O’Toole was Sheriff in Jack Oak County, in the Twenty-Sixth year of the State and the One Hundred and Fifty-Eighth of the Republic, on the Fourth Sunday of Autumn (which, as you have already guessed, was October 15, 1933), a girl was born to Sheriff Slywood O’Toole and his wife, Mary Theresa. This child was to be known in History as Dotty O’Toole and later as Dotty Peisson.

This first is from a small spiral notebook, a common initial site of composition where Lafferty would right his initial draft longhand after establishing character names and an extremely rough chapter outline. Yes, his handwriting is pretty much always like this.

The second is from an early typescript, likely from the copy he would have sent out in 1961 to his then-agent. The biblical cadence is polished, and the lines have been broken into metrical units. This is the only page of this manuscript that has survived.

The third is from the surviving full typescript, the one that Lafferty sent out to Virginia Kidd and then got back from her when she determined she could not sell it. This would be the original for the carbon that then went on to United Mythologies Press in 1989. The metrical units have shifted again and become more typographically complex, even overtly prose-poetic. It’s an affectation, but not of the sort we’re used to from his work.

And then here is the first paragraph as published by UM Press. The typographical complexity proved too much: the formatting is wiped out entirely, de-emphasizing the textual rhythms, turning it into a more standard novel. (Odd since the novel’s dot-matrix art cover is anything but standard.) That’s not the only violence to the cadence, though: note how the parenthetical has expanded, swallowing the date and necessitating extra commas be placed in a passage where before they were very economical.

This isn’t at all to knock Knight, a kind and generous man who took on and actually completed a task that so defeated so many, or the booklets of UM Press, which brought us so many Lafferty works that would otherwise have sat with the rest of his unpublished archives. It’s more to say that, while this is a particularly noteworthy example, there’s definitely more of this kind of stuff in the archives, and I’m hoping eventually we’ll get the chance to take everything back to the manuscripts and have Lafferty editions that reproduce all his idiosyncrasies, and not just the ones we’ve already come to expect.

1 note

·

View note

Text

81.1 Dotty

I will admit that I never saw such hate in the eyes of a three-day old child before. My other two didn’t show any expression at all at that age. Come to think of it, they still don’t. I dread the day when she has teeth, and words.

Most of Lafferty’s families are happy ones. Harried, perhaps, boisterous and borderline dysfunctional for sure, but nonetheless largely content to share the same roof.

The family in Dotty, on the other hand, is decidedly unhappy, and not even in any uniquely Anna Kareninan way: they are poor, and they (the father in particular) are mean, and they are driven further into their meanness by the extremities of their poverty. But where many of Lafferty’s characters remain vibrant, or even grow more so, under the challenges poverty poses (see “The Skinny People of Leptophlebo Street” for a characteristically gonzo example), the O’Tooles shrivel up, abandoning first their mutual respect for each other, and then whatever principles they may have had, and finally the “defective county” they had called home.

This shriveling of the spirit is driven home in a scene of marital rape—nearly unparalleled in all the rest of Lafferty’s works; sex in his fiction, while never explicit, is elsewhere always enthusiastically consensual— which leads in turn to Dotty’s conception. The spitefulness of the begetting is fully matched in the spitefulness of the child begot, who immediately sets to work subordinating her older brother and sister: “It was to take her a few years, surprisingly few, to achieve her dominance over them. The first look she cast on them was one of withering contempt, but at that time she had not the means to implement it.”

Many’s the novel that starts with the birth of its protagonist. Fewer are those that start with their conception, and those almost always signal a comic tone: the canonical example is Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, with Gargantua and Pantagruel lurking not at all subtly in the background. Dotty however turns away from Rabelais and toward Lafferty’s other great fictional inheritance, one that I am more guilty than anyone of minimizing to this point: the multifaceted realism of Honoré de Balzac. Dotty O’Toole (later Peisson) is a character worthy of the French master’s human comedy, probably the most complex in Lafferty’s entire body of work. Yes, including Finnegan, and Hannali, and [insert your own favorite here]; for unlike many of his others, she is not larger than life: she is not out to revolutionize or threaten the world with any great experiments, she is not the embodiment of massive historical forces squaring off against one another, she is not a monster or a sport or a prodigy. She is Dotty, and that is sufficient.

And yet her novel is also as connected to the entire body of work as any other of Lafferty’s tales, or as any of Balzac’s individual volumes is to the rest of the Comedie humaine. Dotty will appear as a background character in most of the Argo volumes, as well as many of the stories set in or around Galveston (Lafferty’s second city, with Dotty as the world’s greatest exponent of the local piano style), or those involving Sour John and nautical adventuring generally, all the way back to Esteban. And her middle name—Theresa, like her mother, like a certain Show Boat—links her to Teresa of Avila, and thus to Fourth Mansions, with its struggles both spiritual and civilizational. Thus it may turn out yet that this intensely personal and private novel, about one soul’s journey toward (and, as often, away from) faith may yet say much about our the wider cultural journey we are all on. One indicator of this latter is another Lafferty rarity: an exact date, in this case Dotty’s birthday: October 15, 1933.

So in all that follows—I’m not doing every chapter individually, both since they’re short and because I want to finish this book and blog eventually—keep this date in mind, first because it places Dotty almost exactly a generation younger than Lafferty himself, and second because of the circumstances of that generational gap: growing up knowing only the Depression and war footing, rather than growing up amid the oil-boom giddiness of 1920s Tulsa and coming to the lean years from the other side. It’s enough to put a little bit of hate in anyone’s eyes.

Composed 1957–58, if not earlier. Rewritten April 1961 and November 1968. Published United Mythologies Press, 1990.

0 notes

Text

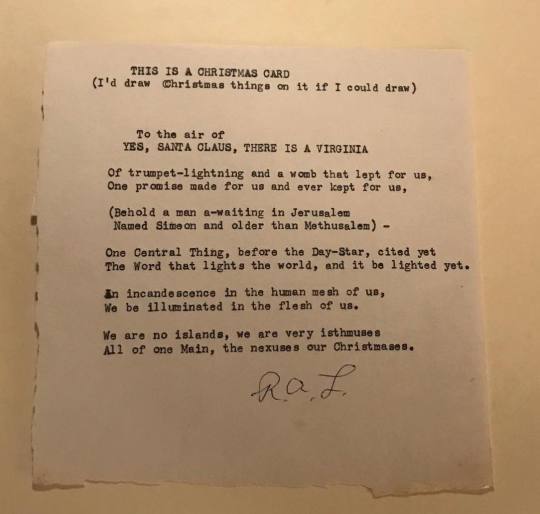

A Lafferty Christmas Poem

Below you will find a previously unpublished—indeed, previously unsuspected—Lafferty poem. I found it while looking through files at the Virginia Kidd Agency, specifically folders on Kidd’s speculative poetry zine, Kinesis.

While it only lasted for three issues, Kinesis published or republished work from Ursula K. Le Guin, Tom Disch, Damon Knight, Joanna Russ, Gene Wolfe, Carol Emshwiller, and James Blish among others...as well as one Raphael Aloysius Lafferty. I knew that much going in, and was able to confirm his contributions (which have never been reprinted elsewhere) to two of the zine’s issues.

What I didn’t know is that Kidd had gathered enough material for at least two more issues of Kinesis, but was unable to bring them out after her mimeograph machine broke down and other concerns crowded out her zine-making time. She held out hope for a while (and that’s a story I’ll tell another time) but in this context the upshot is a fine poem from Lafferty going unread for 45 years or so.

I don’t know whether he meant the poem as a submission, or if he just wrote it to her as occasional verse, and she seized upon it. There’s no carbon in Lafferty’s archive relating to the poem or indicating its existence in any way; if there’s anything in the Kidd Archives, they’ll have to surface as the materials gradually make their way to the University of Oregon, to join the collections of Le Guin, Russ, et al.

Anyway, I’ll leave further analysis of it to others, for now. Hope you enjoy, and that your own Christmas, season, and holidays are merry and bright.

Image follows:

Transcribed text:

THIS IS A CHRISTMAS CARD (I’d draw Christmas things on it if I could draw)

To the air of YES, SANTA CLAUS, THERE IS A VIRGINIA

Of trumpet-lightning and a womb that lept for us One promise made for us and ever kept for us

(Behold a man a-waiting in Jerusalem Named Simeon and older than Methusalem) —

One Central Thing, before the Day-Star, cited yet The Word that lights the world, and it be lighted yet.

An incandescence in the human mesh of us, We be illuminated in the flesh of us.

We are no islands, we are very isthmuses All of one Main, the nexuses our Christmases.

R.A.L.

(My thanks to the Lafferty Estate folks at Locus for granting permission for me to reproduce this poem, and to the good people at the Virginia Kidd Agency for once again letting me invade their workspace and root through their archives.)

548 notes

·

View notes

Text

80.11 Archipelago (end)

There is an advantage in very old and mutilated writings: they are improved by the mutilation. It is the first and the last sheepskins that are always lost or worn. There is no story that is not improved by having its first and last pages lost.

I tried to figure out how to wrap this up without using that quote, but ironically it's so deeply woven into the text that I think it's impossible to work through this section, or this novel, or Lafferty himself, without recourse to an aesthetic of mutilation.

Lafferty is a bricoleur, no doubt, but he's not always one just to take the pieces he finds around him; he's continually active in creating new pieces by shredding what went before. Archipelago, at least on the surface level, is not possessed of the gleefully grotesque mutilation that marks works like Space Chantey, but that's not because it's absent, it's just because he's kicked it up a layer or two.

So while the bodies of Finnegan, Dotty, and the assassin Niccolo Crotolus are assuredly mutilated in the final gun battle, we are denied the details of how exactly the bullets tore into flesh, where the damage was and how deep: information he rarely stints on elsewhere. This may in part be because of an aversion to combat in this "war novel with the war removed," but it also directs our attention to other aspects of the scene and setting.

Here we are given the elements of a blaze-of-glory shootout: a protagonist, his old flame, and an antagonist after the former who will not hesitate to go through the latter. But Lafferty has already ripped up the script before the action starts. Our hero, Finnegan, is not armed and does not return fire; he goes down from the first shot and stays down. Instead, it is the old flame who retorts, who acts as the protector rather than the protected. Even the antagonist is detached from the encounter: he's a hired gun, but one who is oddly drawn to Finn and who makes every effort to ensure that his murder will be accomplished with the victim in a state of grace. (As a side note, anyone know the source of Lafferty's distinction between the "piccolo vendetta" and the "grande vendetta," the revenge unto salvation or unto damnation? The latter is one of his more chilling concepts, though then again Lafferty's own ideas of hell were surprising and complex.)

There is, as often in Lafferty, an overload of imagery and association here, heaped up to the point of confusion. We get here an inverted Garden of Eden, with the serpent (played by Nick the Sidewinder) striking to make sure that the man in question is saved rather than damned, while the woman is completely guiltless. And we end also in a sort of frustrated Pietà, with the Christ figure felled, and Mary unable to cradle his body because she is too busy shooting and being shot.

Meanwhile the book, which started on an island on the Thursday of the creation week just prior to the appearance of man, now concludes on an island on the Wednesday, "the same as the Fourth Morning of the World when God had already made the ocean and let it roll all night and now was ready to place the sun in its course. And He hung it fifteen degrees up in the sky and let it start from there, just above the morning cloud bank. ... Now it was just as it had been in the beginning." Thanks to this chronology, Archipelago loops back on itself just like Devil Is Dead and More Than Melchisedech, just in a more subtle way. And it serves as a reminder that to tell stories is to mutilate time, to break a continuity into discrete units and rearrange those pieces into new and sometimes ungainly configurations.

But it's not just the single timeline of Archipelago that is structurally endangered; the barriers between all the fictions are breaking down. Finnegan, as X will say elsewhere, is the funnel between the worlds of Archipelago and The Devil Is Dead; he is also one of the foci of the world created by Melchisedech Duffey, and characters of that world determine their positions within it with respect to him.

Back from Chapter 7: "Was Finnegan a simple schizo in his living several lives? No. He was a complex schizo. His travels ended only with his life, though X (who claimed to have later congress with him) said they did not end even then. The apocryphal of the Finnegan adventures cannot be separated from the canonical. They raise the question: are there simultaneous worlds and simultaneous people?" As his body is mutilated here, so also are the people he knows and the worlds he inhabits; the two timelines only barely kept separated in Archipelago and The Devil Is Dead bleed fully into one another, and their weird mirroring becomes finally apparent. Many of the characters in Devil are already doubles, but here (in a work written earlier, but perhaps substantially revised after? the textual history is very difficult to unravel) they are revealed as parallel selves to people we have already met in Archipelago. And while we can say that all of us are many people at once and lead potentially many lives across many timelines, that doesn't make it any less confusing for the reader or for the characters themselves—or, we might say, for Lafferty as well. It's telling that Finnegan only realizes this when sketching out the people of his acquaintance, making one last use of his prodigious artistic talent. Inasmuch as Lafferty uses Finnegan's artistic talent as a surrogate for his own (and along with that, his anxieties over squandering that talent), it's tempting to read the early years of his career as an attempt to not become a Finnegan, to have something to point to when the Master demanded an account.

But even if that sort of a crisis (in its original sense of "judgment") is in view, the narration explicitly denies this to the characters involved: "In a crisis there should be a change of attitude. The attitudes of none of them were going to be changed by the shooting." Had Finnegan's attitude changed already? Had Lafferty's? Are there simultaneous worlds, and simultaneous people? It's a difficult set of questions, even beyond the basic impossibility of having a definitive answer for any one of them. Certainly the climax here gives way to anticlimax, as so often with this author who delights in the shaggiest of dogs. And whatever validity we grant to the claims of X—a notorious and renowned liar—this is certainly not the last time we will encounter Finnegan in this life, or in the one to come.

So that's Archipelago: possibly the oldest novel of Lafferty's to be published, and certainly one of the best, even if it took several decades and ultimately immense efforts by Rick Norwood to make it happen even in the limited release it got. If you find a print copy, snap it up! And if not, fortunately, digital copies are now readily available.

One last question about this section, before I move on at long last to Dotty: why Cuba? The action of the book, of course, is in the late 1940s and early 1950s, so this is pre-Revolución. And certainly the bulk of the writing is done before that point. But all the revisions for this novel happen after that point, and in particular after the debacle at the Bay of Pigs, another happening on a Cuban beach. (Albeit one not walkable from Havana, as the scene of the final showdown here.) For Lafferty, Communism was never a red herring, though it might only be one head of a larger hydra. And the book's most persistent subplot centers around Communism: Casey falling away from the Church into its only coherent ideological rival, and subsequently being restored. Not something I have an answer to yet, but I will loop back to it when taking up the later In a Green Tree volumes. Any other questions must be assumed lost in the mutilation in this manuscript.

1 note

·

View note

Text

80.10 Archipelago

"Never get in a distressed egg deal if you can avoid it, Finnegan. It just isn't worth the worry at any price."

We're back with Finnegan, and Finnegan is, however briefly, back with himself. His hold on reality is tenuous, and the state of his soul (if those of the other recensions even have souls) is shaky at best. So it's fitting that he meets in this chapter not just one, but two businessmen who deal in the shaky and tenuous—Hilary Hinton, one of the last pieces of Melchisedech Duffey's World to be moved into place, and "Asking Dan" Askandanakandrian, a theatrical Armenian with unusual insight into Finnegan's disposition. The two of them, respectively, prefer the words "distressed" and "nervous" for the merchandise they traffic in, but either way Finnegan is as risky a prospect as any: hallucinating meetings with his father, beset by Korsakov's psychosis (a form of amnesia peculiar to long-term alcoholics), and promised a violent death for actions carried out possibly in another timeline and certainly in another book.

It may initially seem odd, then, that the chapter focuses on Casey's soul rather than on Finnegan's. But there's much more salvage at stake here than just one banana-nosed painter, though it'll take a detour into Laffertian narrative study to get at it.

For Lafferty is himself a salvage man of no small talent: not for goods or commodities—though we can assume a certain amount of shrewdness thanks to his decades as seller and buyer of electrical parts—but of story forms and elements. Any reasonably well-read person who takes in more than a few lafferties is likely to be struck by how, despite his undoubted originality, he always borrows (sometimes heavily) from sources old and new—a practice of bricolage, as Gregorio Montejo has it, or maybe just "grubbing in the rubble," as Lafferty terms it in his "Day After The World Ended" speech. Here he pulls in the form of the fabliau or bawdy tale, and he's in good company there: Boccaccio's Decameron is filled with them, and several of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales fit the mold as well.