Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

The Ghent Altar (detail), 1432, Jan van Eyck

Medium: oil,wood

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fabric Moths / Bumble Bees

Molly Burgess on Etsy

36K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Salvator Mundi, 1500, Leonardo Da Vinci

Medium: oil,panel

169 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Just amazing as fuck! Holy shit! ♥️♥️♥️♥️♥️

Queen Nefertari playing Senet

Detail of a wall painting depicts Queen Nefertari Meritmut playing Senet (ancient egyptian board game). Tomb of Nefertari (QV66). New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, reign of Ramesses II, ca. 1292-1189 BC. Valley of the Queens, West Thebes.

451 notes

·

View notes

Photo

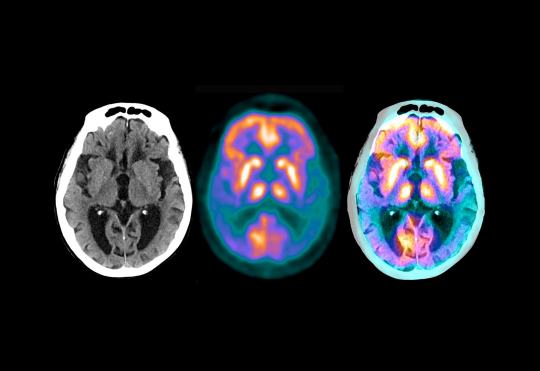

Alzheimer’s Drug Shows Promise in Small Trial

Participants with the disease still declined, but much more slowly than those receiving a placebo, investigators say.

In a small clinical trial, an experimental Alzheimer’s drug slowed the rate at which patients lost the ability to think and care for themselves, the drug maker Eli Lilly announced on Monday.

The findings have not been published in any form, and not been widely reviewed by other researchers. If accurate, it is the first time a positive result has been found in a so-called Phase 2 study, said Dr. Lon S. Schneider, professor of psychiatry, neurology and gerontology at the University of Southern California.

Other experimental drugs against Alzheimer’s were never tested in Phase 2 trials, moving straight to larger Phase 3 trials, or failed to produce positive results. The Phase 3 studies themselves have repeatedly had disappointing results.

The two-year study involved 272 patients with brain scans indicative of Alzheimer’s disease. Their symptoms ranged from mild to moderate.

The drug, donanemab, a monoclonal antibody, binds to a small part of the hard plaques in the brain made of a protein, amyloid, that are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. Patients received the drug by infusion every four weeks.

Participants who received the drug had a 32 percent deceleration in the rate of decline, compared with those who got a placebo. In six to 12 months, plaques were gone and stayed gone, said Dr. Daniel Skovronsky, the company’s chief scientific officer. At that point, patients stopped getting the drug — they got a placebo instead — for the duration of the study.

The small study needs to be replicated, noted Dr. Michael Weiner, a leading Alzheimer’s researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. Still, “this is big news,” he said. “This holds out hope for patients and their families.”

Eli Lilly did not release the sort of pertinent data needed for a thorough analysis, Dr. Schneider said. For example, the company provided only percentages describing declines in function among the participants, not the actual numbers.

The company will provide those data at a subsequent meeting and in an article in a medical journal, Dr. Skovronsky said. Eli Lilly got the results on Friday and was required to report them immediately, he said, because the results can affect Lilly’s stock.

Dr. Schneider, who served on an independent data safety and monitoring board for the study, said he was not permitted to reveal any more data than the company provided.

The trial served as a test of the so-called amyloid hypothesis. The idea is that Alzheimer’s is intimately linked to the accumulation of amyloid in the brain; if amyloid accumulation can be prevented or reversed, the disease may be prevented or cured.

Pharmaceutical companies have spent billions of dollars testing anti-amyloid drugs to no avail, leading many experts to believe that the hypothesis is wrong — or that the only way to treat Alzheimer’s is to start very early, before there are any clinical signs of disease.

The Eli Lilly trial recruited patients not based on symptoms but on scans showing significant accumulations of amyloid in their brains. The researchers also performed scans for a protein, tau, that forms spaghetti-like tangles in the brain after the disease gets started.

“We needed mild to moderate tangle pathology, but not so many tangles that perhaps the disease is beyond hope,” Dr. Skovronsky said.

The primary endpoint, or goal of the trial, was a measurement that combined performance on mental tests of reasoning and memory with assessments of how well the participants performed in activities of daily living, like dressing themselves and preparing meals.

The main side effect was one regularly seen in patients given experimental monoclonal antibodies to treat Alzheimer’s: an accumulation of fluid in the brain. It occurred in close to 30 percent of patients, Dr. Skovronsky said, but most had no symptoms. The effect was seen on brain scans.

While the trial was going on, Eli Lilly started a second Phase 2 trial, Trailblazer 2, hoping that the initial effort would produce results. Those results are expected in 2023.

Dr. Skovronsky said Eli Lilly would be talking to the Food and Drug Administration and regulatory authorities in other countries about helping patients gain access to the drug.

“Certainly the data are exciting,” he said. “But we will have to see what the regulators say.” He has been hoping for 25 years for definitive evidence that the amyloid hypothesis is correct. “This is what we’ve been waiting for,” Dr. Skovronsky said.

By Gina Kolata (The New York Times). Image: Three scans of the brain of a 62-year-old Alzheimer’s patient, four years after diagnosis (Credit Zephyr/Science Source).

161 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Golden Throne of Tutankhamun

The throne of Tutankhamun is made of wood, covered with gold and silver, and ornamented with semi-precious stones and colored glass. Two projecting lions’ heads protect the seat of the throne while the arms take the form of winged serpents wearing the double crown of Egypt and guarding the names of the king.

It was discovered in the Antechamber of the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) beneath the Hippopotamus funerary bed. The throne is called (“Ist”) in ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs after the name of the mother goddess Isis, who was usually depicted bearing a throne on her head as her characteristic emblem. Now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. JE 62028

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

An Intimate Photographic Series Glimpses the Lives of the Children Who Fish in Ghana’s Lake Volta

429 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tattoo Art by Joanna Świrska a.k.a. Dżo Lama

Instagram

Follow CrossConnectMag for more

390 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kleine-Levin Syndrome: Meet the human hibernators

A rare brain disorder causes some people to sleep up to 20 hours a day for weeks at a stretch

There are some young people who are lost to the world. They are locked in a state of slumber, consumed by sleep for 15 to 20 hours each day, sometimes more. Then they finally open their eyes, only to speak monosyllabically or in muddled sentences. In these windows of semi-wakefulness, they sometimes lash out if disturbed, or regress to infancy, clapping their hands and singing nursery rhymes. But soon, somnolence inevitably returns.

Eventually, the spell is broken – but by now, weeks or even months have passed. They awaken fully, usually remembering little or nothing of the time they’ve lost. But their journey isn’t over. Another episode will almost certainly follow, on average three months later but often much sooner than that.

This is Kleine-Levin Syndrome (KLS), a rare and debilitating brain disorder that affects between two and five people in a million, and is sometimes nicknamed ‘Sleeping Beauty’ syndrome as patients behave like real-life ‘sleeping beauties’ from the children’s story. Usually beginning in childhood and adolescence, the youngest reported patient was four years old.

Megan Firth from Oxfordshire, now an 18-year-old law student, developed KLS symptoms aged 13 and had nine episodes last year alone. The most distressing symptom for her isn’t sleepiness; instead it’s derealisation – a dream-like sense of detachment from her surroundings – that can last for days or weeks at a time. Derealisation affects over 90 per cent of KLS patients.

“That’s the part I find most scary,” she says. “It kind of feels like you’re in a bubble and I find it quite hard to tell the difference between what’s real and what I dreamt.” Others report a similar sense of estrangement from their environment or from themselves – they count their fingers to convince themselves of their existence, or fail to recognise their own reflection. They cannot feel water, even as they watch it drip onto their skin, despite it being hot enough to scald. They see a speaker’s mouth move but hear their words out of sync, like they’re watching a badly dubbed movie. Correspondingly, brain scans in some patients show decreased activity in the regions that integrate auditory, visual, and sensory information.

Megan’s mother, Emma, describes another typical KLS symptom during episodes: apathy. “She basically stops communicating with the world. She stops connecting with her friends by phone, she doesn’t want to go out. We’ve a lot of photos of the family going around doing whatever they’re doing and in the background is Megan, fast asleep on a sofa.”

Some patients with Kleine-Levin Syndrome become radically disinhibited, developing a voracious appetite for food known as hyperphagia. Two-thirds eat more – compulsively so, even stealing food or searching for it in dustbins. One drank several bottles of blackberry syrup each day. Another reported: “I would eat four or five peanut butter and jelly sandwiches – without even chewing – very fast, then would start to fall asleep again with food still in my mouth.” Unsurprisingly rapid weight gain is a feature of KLS (an average of 4.6kg per episode, but even up to 13.5kg in some). Disinhibition can also declare itself through hypersexuality. Some masturbate in public (“to the point of bleeding”, said one), expose themselves, or make unwanted sexual advances.

Repetitive compulsive behaviours also feature. “Megan used to watch box sets of Charmed and Miranda again and again, and films like Love, Actually,” recalls Emma. “She actually wore out the Charmed box sets.”

One patient became a habitual fire-starter and another wrote continuously on the soles of his feet. Others pace relentlessly, rock back and forth or pull at their hair.

Tricky diagnosis

Despite these classic features, getting a correct diagnosis is fraught with difficulty, as Megan discovered. For one thing, there’s no specific test for KLS. Instead, it’s identified by its symptoms; that means doctors have to know about it to diagnose it. Teenagers are often labelled as being lazy, or are accused of trying to avoid exams. A mental health misdiagnosis is common, since depression and anxiety are prevalent in KLS, even between episodes. There have been at least two reports of suicide, and 15 per cent of patients describe suicidal thoughts. Some experience paranoia that they’re being watched or about to be eaten, or have hallucinations of snakes, bears and dead bodies, which leads to a misdiagnosis of schizophrenia.

A clinical sleep study, which records brain activity, blood oxygen levels, heart rate, breathing, and leg and eye movements during sleep, can support a diagnosis but cannot cement it. Functional brain imaging is usually limited to research settings and can be difficult to perform during KLS episodes, and may reveal nothing in any case (occasionally there is, however, decreased activity in the brain’s temporal and frontal lobes, thalamus and hypothalamus).

But if diagnosis is challenging, then understanding why KLS happens is even more so. There’s a precipitating factor in 89 per cent of cases – such as a flu-like illness, tonsillitis, sleep deprivation, or alcohol. Researchers think these might trigger an autoimmune and/or inflammatory cascade of events. Dr Guy Leschziner, consultant neurologist and sleep expert at the Sleep Disorders Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital in London, sees some similarities between KLS and other neurological immune disorders.

“In a few cases, inflammation in the brain has been found, although it remains uncertain if these cases were KLS or another disorder causing similar features,” he explains. “KLS remains a syndrome – a collection of clinical features – rather than a specific disease, and so we do not know if all patients have the same underlying cause. My own view is that some patients probably do have inflammation of the brain, while others have a channelopathy – a disorder of the ion channels that mediate electric impulses in the brain.”

There’s a genetic hypothesis, too, even though no specific ‘KLS gene’ has been identified so far and most cases are sporadic. All the same, up to 5 per cent of patients have an affected family member. We even know of two pairs of identical twins with KLS, and one family where a father, three sons and two daughters were affected. These genetic insights haven’t yet, however, led to any new treatments.

Not just lazy

When an episode occurs, Megan knows she must simply wait for it to subside, which is especially demanding when it seems interminable: a third of patients experience at least one episode that lasts for more than a month. Families are advised to keep their children at home (unless significant psychiatric manifestations warrant hospitalisation) and encourage them to drink frequently, and go to the toilet regularly to avoid kidney and bladder damage.

Other people’s perceptions of the disorder are particularly trying, says Emma. “Some have said really dumb things over the years, along the lines of ‘teenagers are just lazy’ or ‘just tell her to wake up’. We often used to say that if Megan had a plaster cast on her leg, no one would say, ‘can’t you just tell her get up and walk?’. When you’re struggling with a 14-year-old acting like a 6-year-old and wondering, ‘what if this episode doesn’t ever end?’, that’s really unhelpful.”

There’s no cure, despite doctors trialling hundreds of medications, electroconvulsive therapy, and even insulin-induced comas. Stimulants like modafanil can improve alertness, but they can also increase aggression and are ineffective against derealisation. Lithium could prevent episodes, but also has potential adverse side effects.

So why has a cure remained stubbornly out of reach? “We have no real inkling of the cause of KLS, which makes life very difficult,” Leschziner explains. “The major reason, however, is its rarity. Getting sufficient numbers of patients into a randomised controlled trial to demonstrate a clear effect is nigh-on impossible,” he adds.

It’s also challenging to establish if a given treatment is truly what’s helping a patient, since the episodes are unpredictable and a KLS spell might have faded without it.

French researchers recently treated 26 patients experiencing episodes exceeding 30 days with high-dose intravenous steroids, which dampen down innate immune and inflammatory responses. The steroids shortened sleeping episodes by up to 11 days in 42 per cent of patients. But this was a retrospective review, not a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Steroids also have significant risks, especially with frequent or prolonged use. Nonetheless, it’s progress for a condition marked by a dearth of research since it was first described in 1862.

Staying optimistic

Megan remains hopeful for her future. KLS often dissipates over time: the median length of time to be afflicted with Sleeping Beauty syndrome is around 15 years, although some 15 per cent of sufferers remain affected even 20 years after onset.

Leschziner is also optimistic about the future of KLS research, referring to recent renewed scientific interest in understanding its genetic and biochemical changes. Some of this research is in its early stages. but maybe one day the spell of KLS will be lifted.

Emma says of her daughter: “Even before she had KLS, I’d like to think we have instilled in her that nothing is impossible.” Perhaps, for Megan and many others, a future without Kleine-Levin Syndrome isn’t impossible, either.

By Dr. Jules Montague (BBC Science Focus). Images by Emmanuel Polanco.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

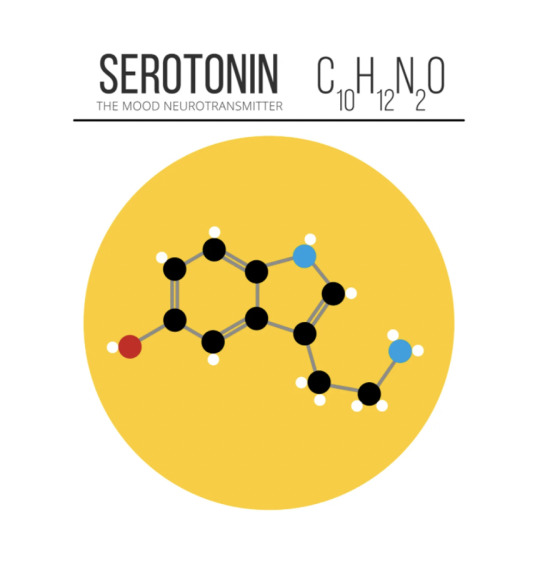

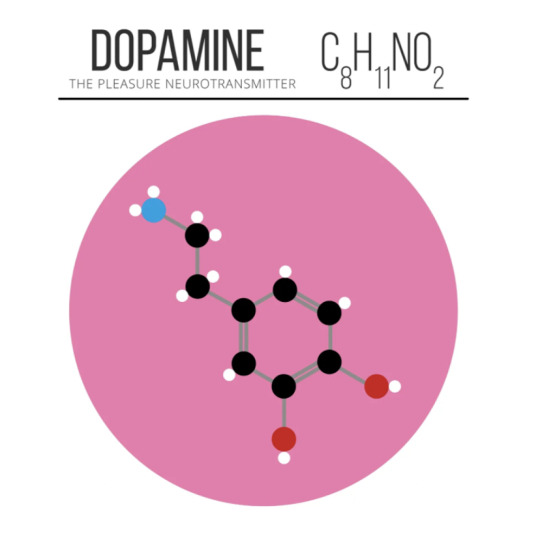

Know your Neurotransmitters

You’ve probably heard about oxytocin in relation to hugging, dopamine in terms of addiction and serotonin in relation to depression. Neurotransmitters are crucial for all sorts of operations in your brain, including mood, appetite and movement. When dysregulated they can lead to undesirable outcomes, including mood disorders like depression and bipolar disorder, addiction and substance use disorders, and psychosis.

You may hear that ‘people with depression have a serotonin shortage’ or ‘addiction is caused by dopamine dysregulation’, and whilst that has some basis in science, the workings of these chemical messengers are somewhat mysterious and definitely more complex than that. Disorders are caused by a number of interactions and neurotransmitters, but for the sake of understanding, let’s keep it simple! In this article we’ll focus on those that are most commonly associated with mood and mental health: serotonin, dopamine, GABA, norepinephrine, oxytocin, and endorphins.

What are neurotransmitters?

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that communicate between the neurons in your brain. Whenever you think, move, learn, feel, perceive or do pretty much anything at all (even when you think you’re doing nothing), electrochemical impulses are rushing along pathways of neurons to make things happen. There are approximately 86 billion neurons in the brain and they do not actually touch each other! Instead they have small synapses where they ‘connect’, gaps of about 40 nanometres between them. For context, there are one million nanometres in a millimetre! The presynaptic (sending) neuron releases these neurotransmitters into the gap, which are picked up by the postsynaptic (receiving) neuron, triggering a response. All this happens a LOT faster than you can say ‘Give me the happy ones please brain!’

Serotonin: The Moody One

We mostly hear about serotonin with regard to mood, particularly that low levels cause depression. People who take antidepressant drugs, are likely to be taking SSRIs — Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors — which work by preventing presynaptic neurons from taking back the serotonin they release into the synapse so there is more available for the brain to use. As well as mood, serotonin is involved in appetite, sleep, memory, impulse inhibition and sexual desire. If you’re low on it, you might experience depression, anxiety, aggression, irritability, impulsivity, insomnia or poor appetite.

How to get enough

The essential ingredient for serotonin is tryptophan, found in salmon, eggs, spinach and seeds, or available as a supplement. Other players in the synthesis and regulation processes include magnesium, zinc, vitamins D, B6, B12 and L-methionine, and deficiencies in any of these could affect your serotonin availability.

How to ‘hack’ it for happiness

Giving, receiving or even witnessing an act of kindness boosts your serotonin, as does sunlight, exercise, and getting a massage.

Dopamine: The Hedonistic One

Dopamine is most commonly discussed for its role in pleasure, reward and motivation. The neurons in your brain that go crazy when you eat cake, have sex, or take drugs are full of dopamine receptors. It is involved in motivation, satisfaction and reward-driven behaviour, as well as movement, sleep, mood and learning. Too much dopamine is linked to aggression, poor impulse control, binge eating, addiction, and has been linked to psychosis and hallucinations in schizophrenia. Low dopamine is seen in movement disorders like Parkinson’s Disease, and may also result in low motivation, energy and sex drive, brain fog, and mood swings.

How to get enough

Dopamine is made from Tyrosine, which your body creates from phenylalanine, which can be found in meat, fish, eggs, tofu, almonds, avocadoes, milk, nuts and seeds. Tyrosine is also available as a supplement. Other players in the dopamine game that you’ll want to get enough of include copper, iron, and vitamins B3, B6, B9, and C. When you eat food that is high in sugar you’ll get a surge of dopamine, however this can lead to the same kind of desensitisation and tolerance as a drug addiction, with your brain needing more and more to get the same dopaminalicious reward. Poor sleep and chronic stress will also deplete your dopamine.

How to ‘hack’ it for productivity

Dopamine’s main purpose is actually motivation rather than pleasure, making sure you enjoy activities like eating and reproducing so you continue to do them. Think about how enjoyable it is planning a holiday, or clothes shopping for a hot date you’re excited about. Set goals, and use your pleasurable dopamine-surge activities as rewards instead of distractions.

GABA: The Chill One

Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) is that neurotransmitter that walks into the chaos and reminds everyone to relax. It is inhibitory, produces a calming effect, reducing anxiety, stress and fear, and helping you sleep. Benzodiazepines like Valium work by enhancing the effect of GABA. If you don’t have enough you may suffer from panic, anxiety and even seizures. GABA is produced naturally in the brain, and low levels can be caused by an inadequate diet, genetics and prolonged stress.

How to get enough

Vitamin B6 is essential for GABA production. You can buy GABA as a food supplement, but scientists aren’t convinced it actually does anything.

How to ‘hack’ it for relaxation

It probably won’t surprise you that yoga, meditation and deep breathing improve your GABA functions. You’ll get the best results if you incorporate them as a regular practice, rather than just when you need them.

Norepinephrine: The Alert One (also known as noradrenaline)

Multitasking norepinephrine functions as a neurotransmitter and a hormone, released into the blood in response to stress. It is involved in attention and alarm response, including the body’s fight or flight response, to help mobilise you for action in the face of danger. It is also implicated in emotions, sleeping, dreaming and is important for memory and learning. Low levels are associated with lethargy, lack of focus and attention, and depression. Overactivity can amplify our normal stress reactions and cause symptoms like anxiety, insomnia, irritability and mood swings.

How to get enough (and regulate it)

Norepinephrine is made from dopamine! It starts with phenylalanine, and goes one step further than dopamine, requiring all the ingredients dopamine requires, and then oxygen and vitamin C to undertake that next transformation. Chronic stress causes prolonged activation of the norepinephrine system, which uses up all your resources, stealing energy from your healing and maintenance systems to prepare for this apparent ongoing threat. Finding ways to reduce stress (see GABA: The Chill One) will regulate your norepinephrine.

How to ‘hack’ it for attention and memory

Coffee’ll do it!

Oxytocin: The Loving One

Oxytocin is both a hormone and a neuropeptide. A neuropeptide is like a large-sized neurotransmitter, and is usually associated with slow, prolonged effects instead of quick ones. Oxytocin is known as ‘the love hormone’ and induces feelings of affection and trust, while inhibiting the brain’s fear response. There you go… this is probably the scientific basis for that hippy notion of fear being the opposite of love! It plays a crucial role in childbirth, breastfeeding, and parental bonding.

How to get enough of it

You can purchase oxytocin as a nasal spray, and it has been shown to promote trust, kindness, emotion recognition and sensitivity. But beware the ‘dark side’ of the cuddle chemical… a 2009 study has shown it can also increase aggression, envy, jealousy and gloating!

How to hack it for those loving feelings

Some studies have shown you can increase oxytocin by meditating, patting your dog or hugging.

Endorphins: The Feelgood One

Most famous for their part in the ‘runner’s high’, endorphins are another neuropeptide. When you feel amazing after a good workout, that’s your endorphins in action. They act as a natural pain reliever, working on the same neuroreceptors as opiates like morphine. They are released as a response to stress or pain, and also during eating, exercising and sex. They improve your mood, lower your stress and boost your self-esteem.

How to get enough of them

Endorphins are produced naturally in the body. We don’t know a lot about endorphin deficiency, but some studies have shown they can become depleted through habitual alcohol use or after traumatic experiences.

How to ‘hack’ them for good feels

You can give yourself a boost of endorphins by eating dark chocolate or something spicy, having a glass of wine, creating music, dancing, doing a workout, meditating, getting a massage, having a sauna or volunteering. Even just having a good laugh will get them working, so watching a good comedy might give you what you need.

Just to reiterate, this is a simplistic explanation and neurotransmitters work in complex ways with each other, with hormones, and with various parts of the body and brain to create different moods and psychological states. We still have a lot to learn about the true nature of these interactions — the brain is a fun and complicated thing to study! But there’s nothing to lose in friending up with your neurotransmitters and giving them the nutrition and stimulus to encourage them. They might even reward you with those oh-so-good brain feels we like so much.

By Larissa Wright (Medium). Gif by AnatomyLearn. Illustration by Compound Interest.

996 notes

·

View notes