Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

When is rebranding not enough?

It’s undeniable that brand campaigns can have major societal impacts and fundamentally alter or deepen consumer beliefs. De Beers was able to convince generations that diamonds were the best – and only – way to prove love and intent to your bride-to-be. Volkswagen convinced consumers of the effectiveness and advantages of smaller cars. And Fair and Lovely preyed on culturally deep-rooted insecurities around skin tone to build a market for their skin lightening products.

It’s no doubt that Indians internalized the racist ideals that revered fair skin, but Fair and Lovely gave it a louder voice, by reinforcing the stereotypes that fairer skin women were somehow better, more accomplished, or more desirable than their counterparts. Any argument Unilever made otherwise is false or out of context. Advertisers and Executives for this and competitor products defended their decisions by comparing the ads for this cream to ads for other cosmetic products – “Why do women want to have red lips? So they use lipstick. Why do women want to have bright eyes? So they use kajal” or “There is a need in our society for fairness creams, so we are meeting that need”. However, we should make the distinction between the user desire the product serves, and the stereotypes that their campaigns perpetuate. It’s one thing for Unilever to create a product that gives women the choice to apply skin lightening products if that’s what they want or makes them feel beautiful (the same argument made by proponents of cosmetic surgery or make-up). It’s another to create an ad campaign that claims that women can achieve previously unattainable things purely due to the color of their skin.

Many years after Nandita Das and WOW campaigned against them, Fair and Lovely finally rebranded themselves in 2020, partially in response to the Black Lives Matter movement. Rebrands can be effective for brands that face aggressive cultural backlash. Abercrombie and Fitch successfully reversed their reputation for upholding unreasonable beauty and size standards by introducing their ‘Curve Love’ and plus-size lines. H&M countered their reputation for unsustainability by releasing an annual sustainability report and creating their clothing recycling program, offering consumers discounts in exchange for donating clothing. Fair and Lovely’s rebrand to ‘Glow and Lovely’, however was met with even more consumer disdain.

People complained that the rebrand was extremely superficial with no meaningful changes to their product or platform. They didn’t even change the images of light-skinned models on their products and ad campaigns. While they promised to make product changes in the future and introduce more representation in their ad campaigns, most people have said it’s not enough and have called for formula changes or product recalls. In both the cases described above, H&M and Abercrombie & Fitch made meaningful changes to their product lines and business strategy in response to the opposition. Fair – I mean Glow and Lovely – still has a long way to go to prove their mettle in this regard and reverse their failed rebrand.

0 notes

Text

Battle of the Cycles: Peloton's diffusion problem

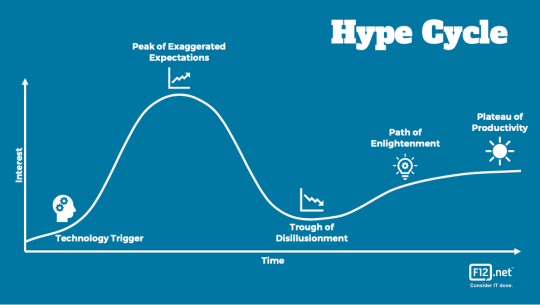

As I read about product diffusion this week and considered Peloton, our chosen Branding Lab company, in the context of the popular product diffusion curve below, I started to wonder if it was more helpful to look at this curve in conjunction with the Gartner Hype Cycle.

Peloton sold it’s first bike on Kickstarter in 2013 and it’s first tablet-powered bike in 2014 – the innovators seemed to love it. As they opened more showrooms and shops in the US, we saw the company move seamlessly to the early adopters. The early majority only came in during the pandemic as home-gyms gained popularity. However, this cycle seems to have stopped before Peloton could even reach the late majority or laggard stage. While we can use the product diffusion curve to understand and contextualize the company’s rise, only the Gartner Hype Cycle can explain their subsequent stagnation.

The Gartner Hype Cycle shows the trajectory that emerging technologies take over time as product diffusion occurs. I believe this is more applicable to a cutting-edge technology company like Peloton than the product diffusion curve alone, as it helps to contextualize the break in the cycle after the early majority phase.

I’d say that Peloton seems to have hit the peak of inflated expectations and is heading into the trough of disillusionment as new sales stagnate.

Their “anyone, anywhere” campaign that aims to rebrand the company as technology-first rather than hardware-first hopes to broaden their consumer case, increase their applicability, and move them closer to the slope of enlightenment and eventually the plateau of productivity. Our Branding Lab goal is to help Peloton smoothly manage this transition as it hopes to overcome the hurdles in their product diffusion process.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fairness via friction

We don't always see companies add friction into a sales process purely for the benefit of the customer.

Prior to Sloan, I was building the Product experience for an online tutoring platform for K-12 students. Because this was India and tech literacy was generally low, our platform leveraged a sales-driven model. And you know the drill at SaaS companies: sales people have extraordinary power and are mandated to close a sale above all else. Every single company-wide KPI focuses on conversion rates and sales targets.

Over time, we found that Salespeople would add discretionary discounts in order to close a sale, often at varying levels. This resulted in each customer being charged a different subscription price. It wasn't long before the cat was out of the bag and customers talked, especially as we saw more word-of-mouth driven growth. We risked serious reputational damage as a company.

Advocating for an ethical customer experience and making a compelling argument for how this could affect the bottom line of our company, I managed to convince the sales director to add friction into the sales process: the sales team could only provide specific discounts after meeting certain strict and objective criteria. While conversion rates dropped a little, we made up for it in a higher customer satisfaction score, a higher retention rate, and even operational improvements due to easier financial reconciliation and subscription management.

Clearly not all friction is bad :)

0 notes

Text

There’s few things that give me more anxiety than this screen. You know it – you’ve seen it before. You’re standing in an artisanal coffee shop – maybe in an expensive NYC neighborhood – you’ve just broken the bank with an $8 iced oat latte, and the cashier flips this screen towards you and stares at you expectantly. What you do next will likely determine the quality of the coffee you get at the other end of the counter, and probably the type of service you get the next time to come to this café to grab a coffee to-go.

These tip screens are a perfect example of an externally imposed nudge (set up by the establishment) meant to encourage a desired behavior (get you to tip more), especially by making the act of tipping a higher-than-necessary amount a mindless decision. While most reasonable places offer the standard three options: 15%, 20%, and 25% (clearly putting their desired option in the middle), I’ve seen some egregious examples like 20%, 25%, and 30% (do I really need to tip $2 on an $8 cup of coffee?!).

Most of these screens will make their 3 pre-selected options large, bright, bold, and centered on the screen. But they will include a teeny-tiny button in the part of the screen your hands are least likely to land on that says ‘Custom Amount’ in the name of choice freedom. Selecting this option adds an extra 2 seconds and multiple clicks to an already agonizing process – I’m least likely to choose it purely because I always want this awkward interaction to end. This screen, combined with the expectant eye contact made by the cashier, nudges – nay, forces – you to tip a high amount, even if you’re just grabbing take-out.

While I completely support the service industry’s fight for a fair wage, the not-so-subliminal nudging in tipping culture has gone absolutely insane. I would absolutely tip between 15-20% at a restaurant, dependent on the quality of meal and service. But to be shown a screen like this after spending $8 on a take-out cup of coffee? Maybe companies should re-evaluate nudges that provoke such strong negative sentiments or customer dissatisfaction.

2 notes

·

View notes