Text

August 24 - Open the Mundus

A mundus is a stone used to cover a ceremonial entrance to the underworld. Ancient Greco-Roman scholar Plutarch believed that the tradition of the mundus came from Etruscan culture, as he wrote in his work Life of Romulus:

Romulus buried Remus, together with his foster-fathers, in the Remonia, and then set himself to building his city, after summoning from Tuscany men who prescribed all the details in accordance with certain sacred ordinances and writings, and taught them to him as in religious rite. A circular trench was dug around what is now the Comitium, and in this were deposited the first-fruits of all things the use of which was sanctioned by customs good and by nature as necessary; and finally, every man brought a small portion of the soil of his native land, and these were cast in among the first-fruits and mingled with them. They call this trench, as they do the heavens, by the name of “mundus.”

The mundus opened on this holiday is the mundus Cereis (of Ceres) on the Palatine Hill in Rome (not the same one mentioned above). As you can see from the passage above, the mundus bears the significance of being a door to the underworld. The actual stone that covered the mundus is the lapis manalis. Opening the mundus allowed the passageway to the underworld to become open to the land of the living. Only on three days of the year was this mundus opened - August 24, October 5, and November 8. According to Varro, no marriages should take place on August 24.

As the name may suggest, offerings to the goddess Ceres are made on this day at the mundus, as She is the guardian of portals to the underworld and, perhaps more obviously at this time of the year, the goddess responsible for an abundant harvest. Offerings were also made to the spirits of the underworld - Di Manes - as were able to leave the underworld and be amongst the living. When the lapis was removed from the opening, the phrase mundus patet (lit. “the world is open") was spoken.

I found one scholar who believed that the mundus served an additional purpose at this time of year to serving as a gateway to the underworld - as a storage house of the seeds from the harvest needed to plant new crops for the next year (Fowler).

According to another scholar, in his essay on the differences between circular and rectangular Roman religious structures (the latter of which were considered “proper” temples by Roman scholars both ancient and modern), the mundus was circular, “on the model of the heavenly hemisphere and that was, in fact, the origin of the name: “mundo nomen impositum est ab eo mundo qui supra nos est; forma enim eius est, ut ex his qui intravere cognoscere ptoui, adsimilis illi” (Frothingham, also quoting Festus).

[August Calendar]

Fowler, W. Warde. “Mundus Patet. 24th August, 5th October, 8th November.” The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 2 (1912), pp. 25-33, via JSTOR.

Frothingham, A. L. “Circular Templum and Mundus. Was the Templum Only Rectangular?” American Journal of Archaeology, Vol 18, No.3 (Jul. - Sep. 1914), pp. 302-330, via JSTOR.

Plutarch, Life of Romulus, 11.1-2, via the University of Chicago. [link]

[Wikipedia - The Mundus of Ceres]

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#classics#cultus deorum

16 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Are you not aware that all offerings whether great or small that are brought to the gods with piety have equal value, whereas without piety, I will not say hecatombs, but, by the gods, even the Olympian sacrifice of a thousand oxen is merely empty expenditure and nothing else?

Julian

“To the Cynic Heracleios” in The Works of the Emperor Julian (1913) edited by W. Heinemann, Vol II, p. 93

(via honorthegods)

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#cultus deorum#classical history

565 notes

·

View notes

Text

JULIAN: THE LIGHT IN THE DARKNESS

Many years before, a man was made deputy of Western Rome on behalf of the Emperor. When the man first arrived to his newly appointed office a woman cried out “This is the man who will restore the temples of the Gods!”

The man was in shock, for he was not a Galilean as his uncle Constantine the Apostate or his mother Basilina. For this man was Julian, a Hellene. A pagan. For now he was in the closet, but even though he did not know it yet, he would one day animate the woman’s word.

Now just over half a decade later, Julian received the news he wanted to hear. He swiftly begun to draft a letter to his friend Maximus of Ephesus who introduced him to the very Gods that his family abandoned decades ago.

“I worship the Gods openly and the whole mass of the troops who are returning with me worship the Gods.” penned the new Augustus, “I sacrifice oxen in public. I have offered many great public sacrifices to the Gods as thanks offerings. The Gods command me to restore Their worship in the utmost purity and I obey Them, yes and with a good will.”

Julian sat down his writing utensil, his hands trembling in excitement. He looked to the heavens and the Gods gave him a warm smile. Like a lighthouse guiding a ship in a storm, they led Julian on the right path and landed him on the purple. The civil war that erupted across the Empire had ended just as fast as it had begun, a bloodless conflict. Julian’s cousin, the now-deceased Emperor Constantius II who had ruled arbitrarily, the very man who years ago murdered Julian’s own father and brother, was dead, having received Thanatos’ cold embrace in a fever far away from any battlefield. Julian, the Caesar of the West, was now recognized as ruler of the East. Julian was now the sole ruler of Rome.

No longer did he have to shave. No, now he was newly bearded, with all the grace of youth. No longer did he attend a mass to listen to the sermons of a bishop. No, now he publicly embraced the message of Heracles, the begotten son of the sun. No longer did he scribe for someone else’s church. No, now he wrote for his Gods, his philosophy and his temples. In his heartfelt gratitude to the Gods who he felt love for like the family he never had, Julian legalized temples to be built again and public sacrifice to be performed once again. Hellenism was to be made the state religion of Rome again, and with the utmost piety.

Julian entered the capital city of where he was born on December 11, 361 through its Golden Gate as sole Augustus of the Roman Empire. The atmosphere was dreamy and energetic. He could hear the cries of joy coming from his people, who appeared en masse to cheer their new Emperor on.

Temples were constructed and great rituals were performed. He reformed the faith and devoutly organized it. He wrote great literature and sang hymns of praise to the Gods. He both refurbished the Oracle of Delphi and even begun helping the Jews rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem. For this is the man who was going to restore the temples of the Gods.

But his time was cut short. After a failed campaign against an aggressive Persia at his country’s borders, he was mortally wounded and laid semi-conscious in bed for three days. He was to die too young to fix the world before it would stop making sense. The light in the darkness was to fade.

An Oracle came before the semi-conscious Emperor who laid in bed. “A fiery chariot whirled among storm-clouds shall carry you to Olympus; loosed from the wretched suffering of men” spoke the wise priest, “You shall attain your Father’s halls of heavenly light, whence you have fallen and come into the body of a mortal man.”

It was June 28th that he was too greeted by a now-somber Thanatos. Serapis came before the dying Emperor and freed Julian from his corporeal bonds. The gentle God lifted Julian’s soul towards the Islands of the Blest; Elysium-bound, through a divine ray of light towards henosis. Helios, the King of All, hugged Julian with warm embrace.

“Whom the Gods love die young.”

-Menander

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#classical history#cultus deorum

283 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Adult Home Study for Hellenic and Roman Polytheists

How do we know what we know about the gods? Much of our knowledge comes from mythology: ancient tales about the gods, fantastic creatures, heroes, and mortals.

There is another meaning of the word “myth”: “widely held, but false, ideas or beliefs,” and all too many of the readily available sources of information about mythology fit that definition. A vast majority of the general population discovers Greek and Roman mythology from motion pictures, video games, and general texts like D'Aulaires Book of Greek Myths and Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. A few more have read Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, Ovid’s Metamorphosis, and Apuleius’ Golden Ass.

Yet more scholarly, in-depth resources are available to polytheists who want to learn about mythology. The fields of history, archaeology, anthropology, religion, literary criticism, art history and psychology all look at mythology from different perspectives.

History examines how the myths were composed, who told or wrote them, and what people said about them.

Archaeology identifies mythological motifs found on objects and structures, and tries to determine their meaning to those who viewed and used them.

Anthropology seeks to understand the cultural reasons for the creation and transmission of myths, and the relation of myth to rituals such as rites of passage such as the transition to adulthood, marriage, and death.

Religion regards myths as sacred stories that explain the creation of the universe, and teach moral truths, and seeks to understand the relationship between mythology, belief, and ritual.

Literary criticism investigates the sources of myths, the oral art of storytelling, motifs and themes, the composition of texts, style, meaning, and comparison of different versions.

Art history focuses on images from mythology throughout history, the religious and symbolic meanings, and artistic techniques.

Psychology delves into the myths as archetypes and symbols, expressions of the collective unconscious, or as a symbolic language to help individuals find meaning and negotiate challenges.

You’ll notice there’s some overlap between these fields. And you should remember that scholars don’t talk to people outside their fields as much as they should.

Many people are initially drawn to the gods after viewing a work of art or reading a story. Some of us have an experience in nature, or in an altered state of consciousness. Becoming aware of a deity is known as an ephipany or personal gnosis, a subjective perception or experience of the presence of the divine. It can be a feeling that a place is sacred, a sense that there is a greater power than ourselves in the universe, or a realization that a higher power has brought about a particular situation.

So, how we know what we know about the gods is…complicated. To really know something, one must regard it from different angles, and take time to understand it. Taken altogether, it’s fairly obvious that each of us necessarily has a different interpretation of mythology, depending on our personal study and experiences.

Unfortunately, many Hellenic and Roman and polytheists have only read the basic mythology titles listed above in their study of the gods. A few more have read books on devotional practice, but most of us haven’t gone much further in our studies. And, because the sources we’ve read just scratch the surface of available knowledge about the gods, our understanding is so superficial that many of us lack the vocabulary to describe our beliefs, and may even harbor misconceptions about one or more gods that harms our relationship with them. Not only does this impede our spiritual progress, but it makes it difficult to talk about our religion to another person. “I worship the gods of the ancient Greeks,” really tells them nothing, except that one is a polytheist.

Since you’re reading this, I assume your religion is an important part of your life, and, if so, your understanding of it deserves to be developed to the best of your ability. I realize not everyone is interested in or has the temperament for research, and that books can be expensive and difficult to obtain. However, most libraries have sections on the fields above, quite a lot of solid information is available online, and it can be done in easy-to-digest bites.

Here are some ideas for study that can help to enrich your understanding and interpretation of mythology:

Read about a Mystery cult, a hero cult, the cult of the nymphs, the Roman Imperial cult or the deified personifications of the virtues in ancient Greece and Rome.

Visit a museum and learn about the archaeology of the regions in which your deities were historically worshiped.

Learn the names and significant events of the different time periods in the ancient Mediterranean. How did agriculture, literacy, mathematics and theater affect society and religion?

Mark the locations of temples dedicated to one of your deities on a map. Are they focused in one area, or are they widespread? What conclusions can you make based on this information?

Read the Orphic hymn(s) about a deity to whom you feel little connection, and read a list of their epithets and cult titles. Think about whether the deity seems more approachable, or just as inaccessible.

Study a work of mythological art. What does it tell you about the meaning of the subject in the era in which it was created?

Read an article on Hellenic or Roman mythology from the viewpoint of of a modern monotheistic or polytheistic religion.

Learn a bit about C.G. Jung’s psychological theories and use of mythic symbols, or Joseph Campbell’s monomyth.

Choose a favorite myth and see how many different versions you can find. Are the versions from different times, different places? Do they have similar or different meanings?

Learn some of the terms used by scholars to describe key concepts in the study of religion. Which of the concepts applies to your own beliefs and practice?

Prepare a meal from an ancient recipe using ingredients that were available in antiquity.

Find out what the ancient philosophers and critics thought about an epic poem or drama.

Select an art or skill favored by one of your gods, study it, and try applying in your own life. For instance, you could dedicate a study of strategy in honor of Minerva and apply one of the techniques to help win a game, or learn a little about weaving to make a wall hanging to honor Athena.

Choose an ancient war. What issue(s) led to conflict? How was it resolved? What were the chief deities of each side? Did religion, omens, or religious rites play any part in the warfare? Were there heroes of the war? Were legends told about them? Were they given offerings such as a monument or hero-shrine?

The more one studies, the more one can deepen their relationship with their deities, the more clearly one may be able to explain their religion to others, and the better equipped one may become to counter criticism of their beliefs.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic pagan#hellenic#hellenic polytheism#classical history#cultus deorum

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pallas Athena/Minerva with her aegis. Roman mosaic (3rd cent. CE), surrounded by a modern (18th century) mosaic depicting celestial bodies and geometrical patterns. Now in the Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican City.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic#hellenic polytheism#hellenic pagan#classical history#cultus deorum

3K notes

·

View notes

Quote

I feel awe of the gods, I love, I revere, I venerate them, and in short have precisely the same feelings towards them as one would have towards kind masters or teachers or fathers or guardians or any beings of that sort.

Julian the Philosopher, in “To the Cynic Heracleios"

(via honorthegods)

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#classical history#cultus deorum

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Popular Divination Methods in Ancient Greece

Haruspicy

In ancient times the haruspex (diviner) interpreted the divine will by inspecting the entrails of a sacrificial animal. First the animal was ritually slaughtered. Next it was butchered, with the haruspex examining the size, shape, color, markings etc. of certain internal organs, usually the liver (hepatoscopy), but also the gall, heart and lungs. Finally, when the animal had been butchered, the meat was roasted and all the celebrants shared a sacred meal.

Ornithomancy

(modern term from Greek ornis “bird” and manteia “divination”; in Ancient Greek: οἰωνίζομαι “take omens from the flight and cries of birds”) is an Ancient Greek practice of reading omens from the actions of birds, equivalent to the Augury employed by the ancient Romans. Although it was mainly the flights and songs of birds that were studied, any action could have been interpreted to either foretell the future or relate a message from the gods. These omens were considered with the utmost seriousness by Greeks and Romans alike.

This form of divination became a branch of Roman national religion, which had its own priesthood and practice. One notable example occurs in the Odyssey, when thrice an eagle appears, flying to the right, with a dead dove in its talons; this augury was interpreted as the coming of Odysseus, and the death of his wife’s suitors.

Bibliomancy

Using texts such as the works of Homer to divine answers. Usually opened at random or using three dice to determine what lines should be interpreted.

Limyran Oracle

A set of 24 stones or potsherds (pottery fragments), each inscribed or painted with a letter of the alphabet. Each stone should have one of the Greek letters (Α, Β, Γ, etc.). Keep the stones in a jug, box, or bag, and when you want to consult the oracle, pick a stone without looking. (One ancient method was to shake the stones in a bowl or frame drum until one jumped out.) This method is similar to the use of rune stones. Stones used in this way would be called psêphoi (PSAY-foy) in Ancient Greek (calculi in Latin); inscribed or painted potsherds are ostraca in Greek (testae in Latin).

Kleromancy

Divination using dice or the knucklebones of sheep, which were called astragaloi. The four sides of the bone were given a numerical value and these were then added together to equal an alphabet character.

Oneiromancy

A form of divination based upon dreams; it is a system of dream interpretation that uses dreams to predict the future. Dreams were also used for healing in Ancient Greece, especially in the sanctuary of Askelpios. Sleeping in the sanctuary of a god was believed to facilitate dreams sent from that particular deity.

Kledon

Divination associated with Hermes, where the person seeking an answer would cover their ears, walk into a busy marketplace and then the first words they heard after uncovering their ears would be their answer. Offerings were made before and after to Hermes.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#cultus deorum#classical history

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pottery fragments [Credit: Ministry of Culture]

Building Complex Revealed In Despotiko >

New buildings have come to light during excavation and restoration works conducted from May 30 to July 7, 2017 at the Sanctuary of Apollo on the uninhabited Greek island of Despotiko (Mantra site), on the west of Antiparos.

Fragment of Kore statuette [Credit: Ministry of Culture]

The results of this excavation season are being considered extremely important for the topography of the sanctuary. Among this year’s findings, the fragment of a marble Kore figurine, dating back to the early Archaic period, part of the block with the foot of an archaic Kouros, and a fragment of the leg of a Kouros stand out.

Read more at https://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.com/2017/07/building-complex-revealed-in-despotiko.html#21P3oD4t3bgR6dMs.99

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Prayers to Venus:

I work at the Getty Villa, and as part of our summer Roman Holidays event, we have an altar to Venus set up, with blank tags so that people can leave prayers to her. I’m not sure if the museum expected the response we’ve gotten, but it’s been really lovely and touching to read all the prayers.

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Prayer to Venus

O Lady Venus

You are far more fierce than people believe.

Your beauty is a deadly weapon,

The sharpest blade there is.

Your beauty is not only physical

But your entirety as well.

The way you help

The way you harm,

Bring together your domain.

I offer you my thanks and my service,

And I hope you accept my offering.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#classical history#cultus deorum

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Prayer to Lady Luna

O Goddess of the Moon,

A foreign yet familiar presence in the sky.

We bask in awe of your soft pale light

Your soft crescent smile among the stars

A tidal force for more than just the ocean.

O Queen of Secrets,

You bring light to the darkness,

Revealing the details of the unknown

Without the sudden illumination of realization.

Your phases bring clarity of understanding the whole.

O Lady of Night,

Hear these praises as I bid thee well.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#classical history#cultus deorum

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Gods Series: Agricultural Divinities

Saturn

Saturn was originally a fabled king of Italy that the Romans ended up identifying with the Greek god Cronos, father of the gods of Olympus, and consequently of Jupiter, Neptune, Pluto, etc. But, in reality, there was little resemblance between the attributes of the two divinities, except that both were considered the earliest gods in their respective countries. On the other hand, there was a resemblance between Ceres and Saturn. The name Saturn was derived from sero, sevi, saturn meaning “to sow”, and he was considered the founder of civilization and social orders closely linked to agriculture. For the same reason, his reign was regarded as the Golden Age of Italy. As agriculture is the source of all wealth, his wife Ops, is the symbol of abundance. Tradition held that the god came to Italy during the reign of Janus, and Macrobius echoes the story in the Saturnalia, where he was given hospitality. At the foot of the hill known as the Saturnian, on the road leading to the Capitoline Hill, a temple was built later on and dedicated to Saturn. According to tradition, the name Latium was said to be derived from the verb late meaning “to be hidden”. Due to the disappearance of Saturn ,who was suddenly ravished from the earth and for that reason, considered a divinity of the lower world. The festival of the Saturnalia was one of the most famous in Roman religion.It was held on the 17 of December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 23. According to tradition, the statue of Saturn was hollowed out and filled with oil, the symbol of fertility in Latium where olive trees grew.

Ceres

Ceres is the original corn mother, the goddess of grain, agriculture and fruitfulness. Some scholars now believe grains were first cultivated for the purpose of brewing beer, not baking bread, and so Ceres is also a goddess of intoxication. She presides over the fertility and abundance of the land, people, animals and is the spirit of cultivation and crops. Her name is believed to derive from a root word meaning “growth”. Related words include kernel, cereal, and cerveza. She eventually became profoundly identified with the Greek goddess Demeter and has become somewhat subsumed by her. Because she was identified with Demeter, her associations with Proserpine were eventually emphasized, but Ceres was originally venerated alongside Liber and Libera, with whom she shared a temple in the Circus Maximus. Her primary festival, the Cerealia, was celebrated from the 12th to the 19th of April; it was a seven-day festival featuring games and processions; another festival, the Ambarvalia, was celebrated around the 29th of May. Some Epithets for Ceres include Flava (golden), Frugifera (bearer of crops), Larga (abundant), Fecunda (fecund), Fertilis (fertile), Genetrix Frugum (progenetress of the crops), Mater (mother), and Potens Frugum (powerful in crops). Ceres was beloved by the masses and was highly significant and respected goddess: the Sibylline Prophesies recommended an annual fast honoring Ceres to ensure an abundant harvest and to avoid famine. She is also a goddess of healing and dream divination.

Bacchus / Liber

Bacchus was a direct copy of the Greek god Dionysus, and eventually was assimilated with the rustic god Liber, one of the ancient italic fertility gods. He is the god who looks after the cultivation of the vines and the fertility of the fields. He is the spirit of libido and vitality. He is the essence of life; male procreative energy. He was celebrated, along with his female counterpart, Libera, on the feast of the Liberalia held on the 17th of March. He was worshiped by the offering of honey cakes, for he was said to have discovered honey. In Ovid’s Fasti, he says in this connection that a poor old woman invited people to buy honey cakes and she broke a piece off each one as an offering on the altar of the god Liber. Ovid observed that children received a free toga on the feast day, because it combined “the grace of youth and that of childhood”, and also because, under the name of Liber, it expresses the freedom of the toga in all its auspices. The festival incorporated processions in which a huge wooden phallis was carried through the fields and streets; repelling the evil eye and beaming fertility energy to women, animals and the land.

Flora

As a very ancient Italic goddess, Flora reigned over springtime and its most colorful expression, with flowers that she helped to blossom and fruit she helped to multiply. She is the wife of Favonius, the wind of the west and the rain that enables trees and plants to find the water they need to grow. The Floralia, festivals dedicated to Flora, took place from the 28th of April to the first of May in the heart of springtime, and they were known for their debauchery and licentiousness.

Pomona

Pomona is the goddess of fresh fruit and fruit trees, especially apples. Her name derives from the Latin pomum, similar to the French pomme or “apple”. The Romans were responsible for first domesticating wild apples, transforming sour fruit into today’s sweet, juicy apples. Presumably Pomona taught them the secret. The eve of her feast day coincides with Halloween. Many scholars believe that at least some of the harvest-related aspects of the modern holiday are vestigial remnants of her old Roman feast.

Vertumnus

Vertumnus was a divinity believed to be of Etruscan origin, although the etymology remains strictly Latin, and comes from the verb vertere meaning “to turn”. The Romans invoked Vertumnus on every occasion involving change: a change of season, a purchase, a sale and the return of floodwaters to their riverbed.Yet, originally, Vertumnus was a divinity that could only watch over harmonious passage from flower to fruit. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, he tells us that Vertumnus was in love with the goddess Pomona, and disguised himself or assumed various shapes to seduce her. Gardeners offered Vertumnus the first flowers and fruits of their gardens or flowerbeds and adorned his statues with garlands of flower buds.

Pales

Pales is one of the divinities of the shepherds and herds. It should be noted that the etymology of her name is the same as that of Palatine, to show clearly that the city was set up and inhabited in the beginning by peasants and that Romulus used a plow to mark out it’s limits.

Bubona

Bubona is the Roman goddess who watches over and protects cattle, and oversees their multiplication and health. Bubona protects the stables and the creatures within, and little shrines to her were made in niches in the walls, or on the pillar holding up the barn roof. Sometimes her images were painted over the feeding-trough as well. Her name is akin to the Latin word for cow or ox, bovis, and the adjective bubula, meaning “relating to cows or oxen”; the English word bovine is related.

Priapus / Mutunus Tutunus

Priapus is the old rustic god of vegetable gardens. He was also a protector of beehives, flocks and vineyards. He was depicted as a dwarfish man with a huge member, symbolizing garden fertility, a peaked Phrygian cap, indicating his origin as a Mysian god, and a basket weighed down with fruit. His cult was introduced to Greece from Lampsakos (Lampsacus) in Asia Minor and his mythology subsequently reinterpreted. When his cult came to Rome he was given the latin name of Mutunus Tutunus. Both parts of the name are reduplicative, Tītīnus perhaps from tītus, another slang word for “penis”. Primitive statues of the god were set-up in vegetable gardens to promote fertility. These also doubled as scarecrows, keeping the birds away. His shrine was located on the Velian Hill, supposedly since the founding of Rome, until the 1st century BC.

-Sources: Roman Mythology by Joel Schmidt / Encyclopedia of Spirits by Judika Illes

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#classical history#cultus deorum

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excavation works resume on 2,100-year-old marble statue of Cybele in northern Turkey

Archaeologists have resumed their efforts to excavate a marble sculpture of Cybele, the mother goddess, in northern Turkey’s Ordu province located on the Black Sea coast.

A team of 20 archeologists led by the head of the Department of Archeology in Gazi University’s, Professor Süleyman Yücel Şenyurt, discovered the ancient artifact last September in the 2,300-year-old Kurul Kalesi, or the Council Fortress.

The 110 centimeters tall sculpture of the goddess sitting in her throne weighs an impressive 200 kilograms and is being showcased in the archaeology museum in Ordu.

According to the Mayor of Ordu, Enver Yilmaz, the excavation work is very important for learning about the history of the region. He explained that the statue of mother goddess Cybele statue was visited by 2000 people in only 45 days. Read more.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#classical history#cultus deorum

216 notes

·

View notes

Photo

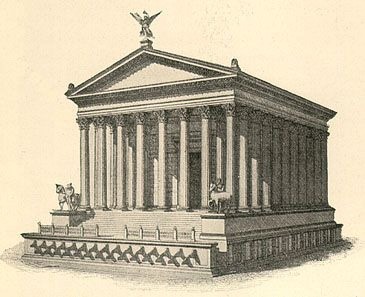

Sorry for the delay, life has had me busy. I present to you the temple of the week.

TEMPLE OF CASTOR AND PULLOX

Castor, aedes: a temple of Castor (or the Dioscuri?) in circo Flaminio, that is, in Region IX, to which there are but two references. Its day of dedication was 13th August (Hemerol. Allif. Amit. ad id. Aug.; CIL I2 p325: Castori Polluci in Circo Flaminio; Fast. Ant. ap. NS 1921, 107), and it is cited by Vitruvius (IV.8.4) as an example of an unusual type (columnis adiectis dextra ac sinistra ad umeros pronai), like a temple of Athene on the Acropolis at Athens, and another at Sunium (Gilb. III.76, 84).

Castor, aedes, templum: * the temple of Castor and Pollux at the south-east corner of the forum area, close to the fons Iuturnae (Cic. de nat. deor. III.13; Plut. Coriol. 3; Dionys, VI.13; Mart. I.70.3; FUR fr. 20, cf. NS 1882, 233). According to tradition, it was vowed in 499 B.C. by the dictator Postumius, when the Dioscuri appeared on this spot after the battle of Lake Regillus, and dedicated in 484 by the son of the dictator who was appointed duumvir for this purpose (Liv. II.20.12, 42.5; Dionys. loc. cit.). The day of dedication is given in the calendar as 27th January (Fast. Praen. CIL I2 p308; Fast. Verol. ap. NS 1923, 196; Ov. Fast. I.705‑706), but by Livy (II.42.5) as 15th July. The laterº may be merely an error, or the date of the first temple only (see WR 216‑217, and literature there cited).

Its official name was aedes Castoris (Suet. Caes. 10: ut enim geminis fratribus aedes in foro constituta tantum Castoris vocaretur; Cass. Dio XXXVII.8; and regularly in literature and inscriptions — Cic. pro Sest. 85; in Verr. I.131, 132, 133, 134; III.41; Liv. cit. and VIII.11.16; Fest. 246, 286;1 Gell. XI.3.2; Mon. Anc. IV.13; Plaut. Curc. 481; CIL VI.363, 9177, 9393, 9872, 10024 — aedes Castorus (CIL I2582.17) or Kastorus (ib. 586.1; cf. EE III.70) appear merely as variants of this), but we also find aedes Castorum (Plin. NH X.121; XXXIV.23; Hist. Aug. Max. 16.1; Valer. 5.4; Not. Reg. VIII; Chron. 146), and Castoris et Pollucis2 (Fast. p103Praen. CIL p.I2.308; Asc. in Scaur. 46; Suet. Tib. 20; Cal. 22; Flor. Ep. III.3.20, cf. Lact. Inst. II.7.9; CIL VI.2202, 2203, although perhaps not in Rome, cf. Jord. I.2.369), forms due either to vulgar usage or misplaced learning. Besides aedes, templum is found in Cicero (pro Sest. 79; in Vat. 31, 32; in Pis. 11, 23; pro Mil. 18; de domo 110; de harusp. resp. 49; ad Q. fr. II.3.6), Livy once (IX.43.22), Asconius (in Pis. 23; in Scaur. 46), the Scholia to Juvenal (XIV.261), the Notitia and Chronograph (loc. cit.). In Greek writers it appears as τὸ τῶν Διοσκούρων ἱερόν (Dionys. VI.13), τὸ Διοσκόρειον (Cass. Dio XXXVIII.6; LV.27.4; LIX.28.5; Plut. Sulla 33), νεὼς τῶν Διοσκούρων (Cass. Dio LX.6.8; App. B. C. I.25; Plut. Sulla 8; Pomp. 2; Cato Min. 27).

This temple was restored in 117 B.C. by L. Caecilius Metellus (Cic. pro Scauro 46, and Ascon. ad loc.; in Verr. I.154; Plut. Pomp. 2). Some repairs were made by Verres (Cic. in Verr. I.129‑154), and the temple was completely rebuilt by Tiberius in 6 A.D., and dedicated in his own name and that of his brother Drusus (Suet. Tib. 20; Cass. Dio LV.27.4; Ov. Fast. I.707‑708). Caligula incorporated the temple in his palace, making it the vestibule (Suet. Cal. 22; Cass. Dio LIX.28.5; cf. Divus Augustus, Templum, Domus Tiberiana), but this condition was changed by Claudius. Another restoration is attributed to Domitian (Chron. 146), and in this source the temple is called templum Castoris et Minervae, a name also found in the Notitia (Reg. VIII), and variously explained (see Minerva, Templum). It had also been supposed that there was restoration by Trajan or Hadrian (HC 161), and that the existing remains of columns and entablature date from that period, but there is no evidence for this assumption, and the view has now been abandoned (Toeb. 51). The existing remains are mostly of the Augustan period (AJA 1912, 393), and any later restorations must have been so superficial as to leave no traces.

This temple served frequently as a meeting-place for the senate (Cic. in Verr. I.129; Hist. Aug. Maxim. 16; Valer. 5; CIL I2586.1), and played a conspicuous rôle in the political struggles that centred in the forum (Cic. de har. resp. 27; de domo 54, 110; pro Sest. 34; in Pis. 11, 23; pro Mil. 18; ad Q. fr. II.3.6; App. B. C. I.25), its steps forming a sort of second Rostra (Plut. Sulla 33; Cic. Phil. III.27). In it were kept the standards of weights and measures (CIL V.8119.4; XI.6726.2; XIII.10030.13 ff.; Ann. d. Inst. 1881, 182; Mitt. 1889, 244‑245), and the chambers in the podium (see below) seem to have served as safe deposit vaults for the imperial fiscus (CIL VI.8688, 8689),3 and for the treasures of private individuals ( Cic. pro Quinct. 17; Iuv. XIV.260‑262 and Schol.). No mention is made of the contents of this temple, artistic p104or historical, except of one bronze tablet which was a memorial of the granting of citizenship to the Equites Campani in 340 B.C. (Liv. VIII.11.16).

The traces of the earlier structures (including some opus quadratum belonging to the original temple; see Ill. 12) indicate successive enlargements with some changes in the plan of cella and pronaos (for the discussion of these changes and the history of the temple, see Van Buren, CR 1906, 77‑82, 184, who also thinks that traces can be found of a restoration in the third century B.C.; cf. however, AJA 1912, 244‑246). The Augustan temple was Corinthian, octastyle and peripteral, with eleven columns on each side, and a double row on each side of the pronaos. This pronaos was 9.90 metres by 15.80, the cella 16 by 19.70, and the whole building about 50 metres long by 30 wide. The floor was about 7 metres above the Sacra via. The very lofty podium consisted of a concrete core enclosed in tufa walls, from which projected short spur walls. On these stood the columns, but directly beneath them at the points of heaviest pressure travertine was substituted for tufa. Between these spur walls were chambers in the podium, opening outward and closed by metal doors. From the pronaos a flight of eleven steps, extending nearly across the whole width of the temple, led down to a wide platform, 3.66 metres above the area in front. This was provided with a railing and formed a high and safe place from which to address the people. From the frequent references in literature (see above) it is evident that there was a similar arrangement in the earlier temple of Metellus. Leading from this platform to the ground were two narrow staircases, at the ends and not in front. The podium was covered with marble and decorated with two cornices, one at the top and another just above the metal doors of the strong chambers. Of the superstructure three columns on the east side are standing, which are regarded as perhaps the finest architectural remains in Rome. They are of white marble, fluted, 12.50 metres in height and 1.45 in diameter. The entablature, 3.75 metres high, has a plain frieze and an admirable worked cornice (for the complete description of the remains of the imperial temple previous to 1899, see Richter, Jahrb. d. Inst. 1898, 87‑114; also Reber, 136‑142; D'Esp. Fr. I.87‑91; II.87; for the results of the excavations since 1899, CR 1899, 466; 1902, 95, 284; BC 1899, 253; 1900, 66, 285; 1902, 28; 1903, 165; Mitt. 1902, 66‑67; 1905, 80; for general discussion of the temple, Jord. I.2.369‑376; LR 271‑274; HC 161‑164; Théd. 116‑120, 210‑212;a DE I.175‑176; WR 268‑271; DR 160‑170; RE Suppl. IV.469‑471; Mem. Am. Acad. V.79‑1024; ASA 70; HFP 37, 38).

This temple was standing in the fourth century, but nothing is known of its subsequent history, except that in the fifteenth century only three columns were visible, for the street running by them was called via Trium Columnarum (Jord. II.412, 501; LS I.72, and for other reff. II.69, p105199, 202; DuP 97). In the early nineteenth century it was often wrongly called the Graecostasis or the temple of Jupiter Stator.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#classics#classical history#cultus deorum

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Emperor Julian by Sasha Chaitow, 2015. Image source: X

June 28 marks the death of the Emperor Julian in 363 CE, three days after being mortally wounded in battle against the forces of the Sassanid ruler Shapur II at Ctesiphon, Iraq. His body was entombed at Tarsus, in complaince with his wishes. He was accorded divine honors by the Roman Senate, and is known to have received worship by individuals and cities who still observed the Imperial Cult.

Julian was the last great pagan Emperor of Rome, though there was at least one later Emperor who practiced traditional religion, and several more who were tolerant of, or even sympathetic to, their subjects who worshiped the old gods. He was also not the final Emperor of Rome to be deified; that practice continued, even among the Christian Emperors, into the 6th century.

“…Julian surprised the world by an edict which was not unworthy of a statesman or a philosopher. He extended to all the inhabitants of the Roman world the benefits of a free and equal toleration; and the only hardship which he inflicted on the Christians was to deprive them of the power of tormenting their fellow-subjects, whom they stigmatized with the odious titles of idolaters and heretics. The Pagans received a gracious permission, or rather an express order, to open ALL their temples; and they were at once delivered from the oppressive laws and arbitrary vexations which they had sustained under the reign of Constantine and of his sons.”

- Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 23

More about Julian here.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpolytheisim#romanpagan#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#classical history#cultus deorum

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

ASKLEPIOS SOTER: A JULIAN HELLENIC INTERPRETATION ON THE IDENTITY OF THE SAVIOUR OF MAN & SUB-LUNAR DEMIURGE

Asklepios is the saviour of the whole world, operating on a lower level than His father the Celestial Demiurge, Helios. Asklepios is “contained” within Helios, however existing on a lower level. He is motherless, and even before the beginning of the world Asklepios was at Helios’ side. The Celestial Demiurge engendered Asklepios from Himself among in Intelligible Realm, and through the light of His visible counterpart the Material Sun revealed Asklepios to the Earth. Asklepios, having made His visitation to earth from the sky, appeared at Epidaurus singly, in the shape of a man; but afterwards He multiplied Himself, and by His visitations stretched out over the whole earth His saving right hand. He came to Pergamon, to Ionia, to Tarentum afterwards; and later He came to Rome. And He travelled to Cos and from there to Aegae. Next He is present everywhere on land and sea. He visits no one separately, and yet He raises up souls that are sinful and bodies that are sick.

Asklepios heals our bodies, and along with Apollo and Hermes aids the Muses in training our souls. The art of healing is derived from Asklepios, whose oracles are found everywhere on earth, the God granting to us a share in them perpetually. When people are sick, it is Asklepios who cures by prescribing remedies and healing dreams. Asklepios does not heal mankind in the hope of repayment, but rather in an act of selflessness, to fulfill His own function of beneficence to mankind.

Asklepios, along with His brother Dionysos, co-reign as the Sub-Lunar Demiurges, the Demiurges whose activity focuses on the sub-lunar level, literally the realm “Below the Moon”, or alternatively “Below the Heavens”, which means the material cosmos below the sphere of the moon. The Sub-Lunar Realm is part of the Encosmic Realm, being the realm that we live in, and Iamblichus splits the Sub-Lunar Realm into three; the aether, ruled by Kronos, the air, ruled by Rhea, and the sea or water ruled by Phorcys. It is the Sub-Lunar Demiurges’ roles to direct the Sub-Lunar Realm and all within it, including human souls who fall into it and daimons whose job is to lead them upwards again. They separate and re-assemble the logoi (manifestation of the Forms shaped and directed by the Celestial Demiurge) in the Realm of Generation. Dionysos represents the Sub-Lunar Demiurgic power of separation or division. As He is torn asunder by the Titans themselves, Dionysos is the activity of dividing wholes into their constituent parts, separating the logoi from the bodies within which they are contained. Asklepios, however, is a God of healing, and the ill go to His sanctuaries to receive healing dreams. Whereas Dionysos takes things apart, Asklepios restores them, putting the logoi appropriate to us in their proper order.

The Sub-Lunar Demiurges are imitators, not creators. They are called “image-maker,” eidolopoios, and “purifier of souls,” kathartis psychon. As souls descend into generation, Dionysos removes from them logoi inappropriate to their nature, and Asklepios attempts to give those souls a life appropriate to the logoi properly belonging to them. In doing so the Sub-Lunar Demiurges also deeply binds the soul into the realm of generation. They are the master daimons, megistos daimon, especially over personal daimons.

GLOSSARY

Celestial Demiurge: The Supreme Demiurge, the God of Gods who crafts the cosmos; Zeus-Helios.

Demiurge: An artisan God responsible for the creation and maintenance of the universe.

Intelligible Realm: Where Plato’s Ideas derive from and where the supreme principle, The One, presides over. Also called the Noetic Realm.

Intellective Realm: Intermediate realm between the Intelligible Realm and our Realm of Generation. Where the Forms manifest as Logoi. Also called the Noeric Realm.

Logoi: Manifested Forms that the Celestial Demiurge directs and forms to create our universe.

Ousia: Substance, which implies being.

Phenomenal Realm: The physical cosmos where the Hypercosmic, Hyper-encosmic (a medium realm) and encosmic realms are.

Realm of Generation: Resides in the Phenomenal Realm, specifically in the Encosmic Realm. It is where our material existence presides. Includes everything from Athene’s domain of the circle of aethyr above the Seven Planets to the Earth.

Bibliography

Iamblichus, and Emma C. Clarke. Iamblichus on The mysteries. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003.

Kupperman, Jeffrey S. Living theurgy: a course in Iamblichus philosophy, theology and theurgy. London: Avalonia, 2014.

Sallustius, “On the Gods and the Cosmos”, 4th Century AD, accessed May 17, 2017, http://www.platonic-philosophy.org/files/Sallustius%20-%20On%20the%20Gods%20(Taylor).pdf

Shaw, Gregory. Theurgy and the soul: the Neoplatonism of Iamblichus. Second ed. Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2014.

Julian, and Wilmer Cave (France) Wright. The works of the Emperor Julian. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpagan#romanpolytheisim#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#classical history#cultus deorum

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paganism/Witchcraft is not an excuse for appropriation.

Don’t wear dreads if you’re white. Don’t call yourself slurs if you can’t reclaim them (looking at you, white “g*psies”). Don’t claim to have a spirit animal if you’re not Native. If there is something that’s important to a culture, and you use it without permission and especially without respecting the history, you are being oppressive.

#RomaAeternaOfficial#romanpolytheisim#romanpagan#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic#cultus deorum#classical history

308 notes

·

View notes