The Royal Alberta Museum is devoted to the history of Alberta’s people and landscapes.The new RAM is the largest museum in western Canada.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Curating your ultimate RAM visit

As the largest museum in Western Canada, we understand that it may feel a little daunting to visit RAM – where do you start? What are the must-see objects? What if you don’t have a lot of time?

Fear not: We’ve compiled a collection of highlights that will satisfy any visitor, from the casual dabblers to history buffs!

The Nature Lover

If you’re looking for dazzling geodes, wild animals, and ancient creatures, you’ll want to head up, up, up to the Natural History Hall.

Take a left to enter the world of gems and minerals. The giant purple geode or holey concretion might capture your attention at first, but don’t dismiss the small specimens just yet. Did you know we have a piece of Mars on display?

If you’ve ever wondered what the oldest fossil in the RAM collection is, seek out the stromatolites in the Ancient Alberta section. They’re approximately 1.4 billion years old!

While the massive Ice Age mastodon and mammoths are sure to catch your eye, you may be fascinated to discover the story of the Saiga Antelope. She may look like a Star Wars character or some not-so-distant cousin of ALF, but she’s definitely from this planet. Unlike most Ice Age creatures, the saiga antelope didn’t go extinct. In fact, you can still see them today in Russia and Central Asia.

Press on to the Wild Alberta gallery, and see if you can find the living hognose snake in one of the dioramas. Here’s a hint – it may be just under your nose… or your feet!

The Avid Anthropologist

From the earliest people to Alberta today, you won’t find your typical textbook history in the Human History Hall. Once you enter through the gallery doors, head clockwise to catch these exhibits.

For Cree communities, winter is the time that you share stories – and certain stories can only be shared in winter! Visit the interactive display of Wîsahkêcâhk, under the second panoramic landscape from the left, to hear storyteller Billy Joe Laboucan recounting one of the Cree trickster’s humorous adventures. This story can only be heard in the museum after the first snowfall. Once the snow melts, the story is gone until next year when the snow flies again!

Head around the corner, and step back in time through the temporary exhibition, I Am From Here, where you can visit a long-gone diner, welcome home a railroad porter, and meet the descendants of early Black settlers in Alberta.

Many First Nations and Métis women gathered together in the winter, sat by the firelight making beadwork, embroideries, quillwork or moose-hair tuftings, while sharing tea and catching up on gossip. Some mothers would coax their children into bead-sorting duties – separating them out into small parcels by colour and size. Seek out the Sewing for a Living exhibit to see examples of Indigenous women’s incredible talents with beads, quill, needles and thread.

You saw the biplane hanging in the lobby, now see the flight suit of the man that flew it. Wilfrid Reid (Wop) May, First World War flying ace served as a fighter pilot in the First World War. Head to the display case below the yellow airplane to check out how many layers he would wear while flying!

Be sure to take your time in the circular What Makes Us Strong gallery. This space brings together displays from each of the five largest Indigenous nations in Alberta: Nehiyawak (Cree), Niitsitapi (Blackfoot), Dene, Nakoda/Nakota and Métis. Stay to watch the 360-degree video – like the vibrant communities it portrays, there is neither beginning nor end.

The Curious Kiddo

If your little one is a seasoned RAM visitor, they may want to head straight to the Children’s Gallery, but don’t miss out on the great interactive exhibits in the history halls as well!

In the Human History Hall, young visitors can learn about how early peoples hunted the extremely speedy pronghorn antelope; travel from Pigeon Lake to Fort Edmonton with a team of “little dogs;” and giddy-up to the Calgary Stampede atop Champion, the mechanical horse.

Upstairs in Natural History, kids can walk on the wild side. Feed a baby pelican, don your feathers for a ruffed grouse dance-off, and practice your flirting skills with the humming birds.

Then, of course, head to the Children’s Gallery, where kids can make a volcano, control the wind, or put on a show! If this doesn’t tire them out, nothing will!

The Lover of All Things Bugs

This one is for all you brave visitors who aren’t afraid of a few extra legs.

If you want to start big, head to the right once inside the gallery and seek out the goliath bird eater tarantula. This species, found in South Africa, is the heaviest spider in the world. Can’t see her? Check inside the hollow log.

Prefer something a little smaller? See if you can spot the stalk-eyed fly. The males of this tropical insect use their eyestalks to stare down competitors – the biggest span usually wins!

Some people may think the giant African millipede is creepy, but not you! You recognize the important job these many-legged invertebrates play in breaking down plant material and rotting fruit. Thanks, millipedes!

What is the coolest creature in the Bug Gallery, you ask? The peacock mantis shrimp, named Lyle, is certainly a contender! Brilliant colours and an incredibly powerful punch make this crustacean a must-see.

The Instagrammer

Even if you’re just here to “do it for the ‘gram,” we won’t judge. If you’re looking for the Instagrammable spots of RAM, look no further.

Before you enter the building, be sure to walk past the Ernestine Tahedl murals on the south side of the museum. These murals previously adorned the former Canada Post building that used to occupy this site. A little #yegdt history, the vibrant pops of red, and that natural light make for a great picture!

Of course, when you first walk in, you’ll want to snap a photo with our two Mammoths in the lobby – you can’t get a more iconic “I visited RAM” snap.

Head up to the Ice Age creatures in the Natural History Hall for some dramatic snaps of megafauna. Yeah, the sloth really was that big. Be sure to include yourself in the photo for scale!

Back downstairs, you’ll need to get a shot of Molly the pickup truck in the back corner of the Human History Hall – because you can’t get much more “Alberta” than a pickup truck.

And of course, don’t forget to hashtag your snaps with #RoyalAlbertaMuseum, or tag us so we can see them!

@royal_alberta_museum

@RoyalAlberta

Royal Alberta Museum

Bonus Stops!

Phew! You’ve covered a lot of ground in this visit. It’s probably time to treat yourself, right?

First, refuel and re-caffeinate at the Café. Have you tried the bison burger? Or maybe you’re more of a donut person – we’ve got you covered there, too.

Finally, exit through the Museum Shop! With hundreds of unique items from local vendors, including jewellery, home accents, art, food, plus toys your kids will be begging for, and RAM swag to show your museum love, you’re sure to find something you’ll love.

These are just a few ideas. We want to hear from you! What are your go-to stops when you visit RAM?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Babies Wrapped in Love

By Rogan Alexis

This summer, RAM has two Indigenous Student Museum Interns working in various areas of the museum. Each of them has written a blog post about a project they’re creating during their time at RAM. Read the other posts here:

Barking Up the Right Tree (Part 1) by Skye Haggerty

The Basket Tree (Part 2) by Skye Haggerty

Aba Washde Rogan Alexis mugabi, waka mne mace dahad Good day I am Rogan Alexis from creators lake

I’m Indigenous to Turtle Island and was raised on Alexis Nation. I remember when I was young, my mom was always sewing and beading. She would make the coolest things: medallions, earrings, vests, regalia and so much more. She tried to teach us how to do the things she did, but I never had the patience for it as a kid. I’d start beading a rope, but not finish; start a loom and leave it for weeks.

But I’ve enjoyed sewing for quite some time now, and I’m rather good at it, but I am always learning and becoming better. If it wasn’t for my mom, I wouldn’t be sewing at all. She always encourages me, even when I’m down. One project I wanted to sew was a moss bag. My mother agreed to help me sew one, taking the same steps that she took when she sewed my moss bag when I was a baby.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m still in a moss bag” -Skye

Ugiba (moss bags) For those who don’t know, moss bags are like little baby holders. Historically, moss bags would be lined with two layers of Higda (moss) from shna (muskeg/swamps) to act as a diaper. The bottom layer is coarse or rough to add extra cushioning. The top layer of moss is softer so the baby is comfy and supported. You have to dry the moss first or else it may contain bugs or give the baby a rash. After the moss is dried it can be stored and used year-round. We chose moss because it is biodegradable, and we always tried to avoid harming the earth as much as possible. A moss bag is just one variation of a baby sack.

Who makes moss bags? Anyone. Anyone can make one. You just have to be respectful of the cultures and the people who provided you the info.

What materials are needed to make a moss bag? Everyone has their own style, design and preference for material, but here are the general materials I used to make my moss bag:

Soft Material for the inside: You want to choose material that the baby will feel comfortable and warm in. I chose a soft pink fabric. You often see receiving blankets along the inside.

Outer Material: can either be something pretty or practical. This is the fabric that people will see.

Decorative pretty things: like beads, or ribbon. These decorate the sides of the bag. I like to make baby look bougie and so I try and make the difficult and designs and many different colours

Material strips: to lace the moss bag

Two leather patches: to weave the material strips through

Thread and needle

Pen and scissors

Pins

How to make one.

1) First, pick out your two fabrics - You need a soft fabric for the inside, where the baby will lay, and a stronger outer fabric which will give the moss bag extra support. My mother taught me to measure the length with my thumb and index finger. Three hand-lengths should be enough to make a newborn moss bag.

2) Next, you’ll cut the inner fabric. Fold in half then make the cut like so.

3) Do the same with the outer fabric. It’s a good idea to use the inner fabric as a template. You can also draw it out if it helps

4) Now you can decorate the outer fabric with your ribbon, beads or other decorations. If they stick out from the fabric, you’ll want to add them to the sides.

5) Pin down the curved side of the fabric and sew each piece separately making the shape of two half canoes.

6) Then, sew the soft fabric onto the inside of the outer fabric. You’re almost done! Unfortunately I don’t have photos of this step.

7) Finally, you’ll sew your two leather patches along the top opening. Be sure to leave spaces to weave the strips through, to lace the baby in.

That’s it! You’ve got a moss bag! Now all you have to do is put a baby in it. Good luck!

Ishnish, thank you

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Basket Tree (Part 2)

By Skye Haggerty

This summer, RAM has two Indigenous Student Museum Interns working in various areas of the museum. Each of them has written a blog post about a project they’re creating during their time at RAM. Read the other posts here:

Barking Up the Right Tree (Part 1) by Skye Haggerty

Babies Wrapped in Love by Rogan Alexis

For many Indigenous Peoples, the availability of birch and spruce trees made their bark and roots essential materials for the creation of every-day items such as baskets. Not only is this material extremely practical, it also provides a unique medium to showcase artistic talent.

Some of my favourite memories involve going into the bush with my grandmother to collect the papery birch bark for her crafts. In the winter, I’d get to chew on spruce gum while she collected roots from the muskeg in our backyard. Sometimes these trips came with tea and cold bologna sandwiches, sometimes not, but they always included a teaching or two about Grandmother Tree and her gifts to us.

In this two-part blog post, I’ll explore the importance of these materials, the process of harvesting them, and a few of the traditional crafts my grandmother taught me to make from them. Read part 1 here.

The Basket Tree

After harvesting the needed materials for a birch bark basket from the forest in my prior post, my grandmother and I set to making the baskets (and a few other items too).

The baskets created from this natural material can be used for anything ranging from berry-picking to water hauling (if sealed with a resin commonly called pitch) to being a decorative container for household knick-knacks. To create a birch-bark basket you’ll need a few more tools:

A good pair of scissors

A pencil or pen knife

Construction paper

Sinew or spruce root

A needle

A dowel for puncturing holes

Clamps or paper clips

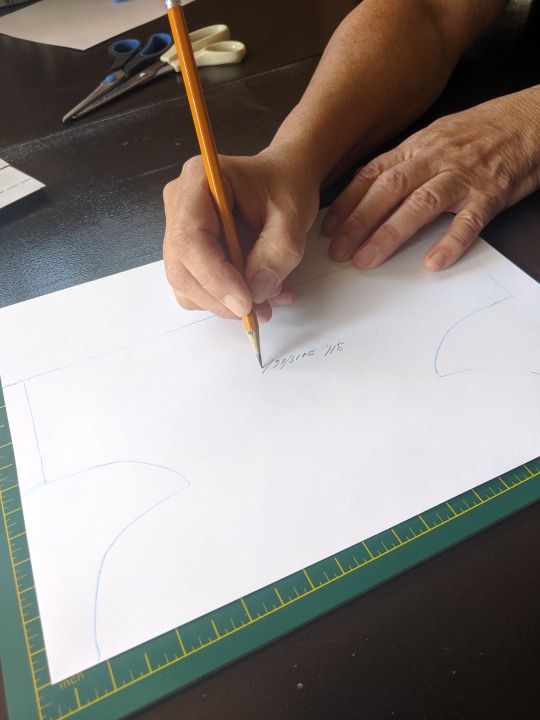

Now, you draw your pattern!

Once you have a pattern drawn and cut out, it can be traced with pencil onto the bark or scored with a penknife.

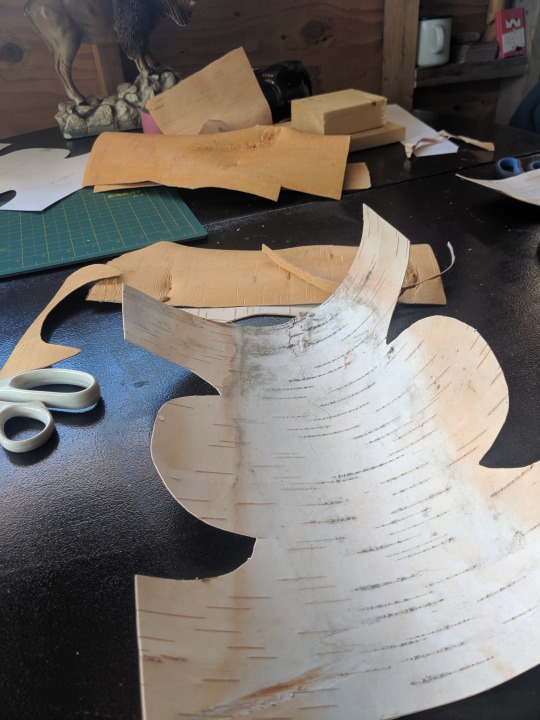

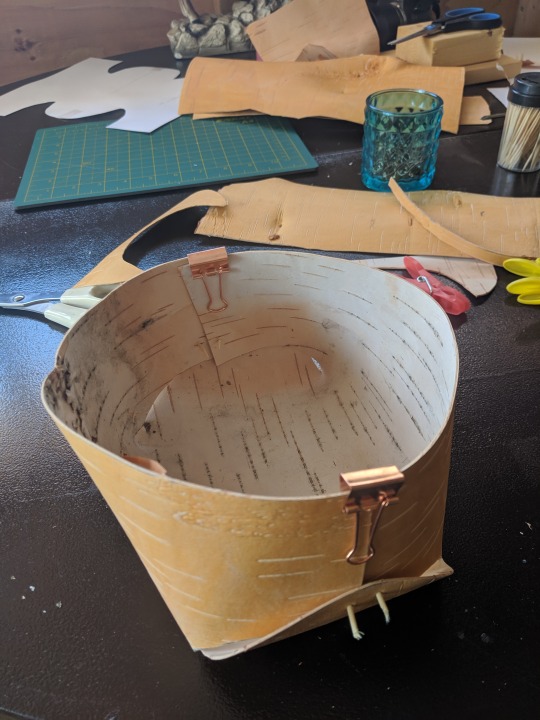

Cutting out the pattern is easy enough, but you want to work with the natural curl of the bark. Utilizing the bark’s natural tendency to curl opposite of its original shape by making the papery exterior the interior of the basket lends additional support to the basket’s structure. The sides can be easily folded and held together by paper clamps while you stitch it together.

Sometimes the bark is thin enough to puncture with a needle, but it’s best to use a dowel to poke the holes and plan how you want the stitching to go. A decorative trim can be made from the scrap of the bark. It adds strength to the basket’s structure and can be attached using either the same stitch or something different.

And here we have the finished products!

My mom also took a moment to make my knife a sheath from two long strips of bark woven together. She also took the time to make a conical tool called a moose-caller out of the remaining birch bark for her nîcimos (sweetheart).

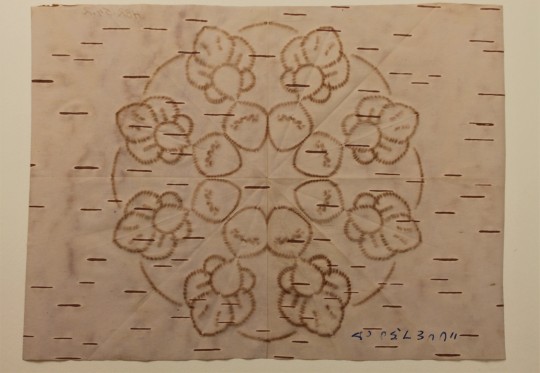

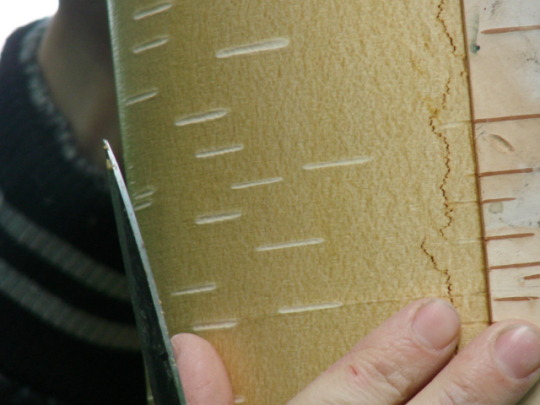

Birch bark biting is another art that utilizes the unique qualities of the bark. Stripped into thinner layers, the bark becomes paper that can be used for both artwork and for transferring patterns. Birch-bark biting was traditionally done by women and served as a kind of friendly competition between them. The individual would bite her pattern into the bark using her incisors and picture the design in her mind. Holding up the bark to the light would reveal if the pattern had transferred all the way through. Once satisfied with the design, it could be transferred onto any item they intended to do bead or quillwork on.

This was done by laying the bitten pattern over the item and using a thin layer of ash or chalk to transfer the image. The ash or chalk would fall through the holes in the bark and recreate the pattern on the other side.

An example of birch bark biting from the RAM Indigenous Studies collection, created by Angelique Merasty from Beaver Lake, Saskatchewan.

With the availability of pencils, paper, and other materials the practice of birch bark biting is not used as frequently but there are still practitioners that produce beautiful pieces of artwork such as Halfmoon Woman (Pat Bruderer). The biting, of course, takes many hours of practice and as Angelique Merasty once said, it takes “wasting a lot of birch bark” to develop the art.

These objects showcase a union of utility and art that is characteristic of many Indigenous creations. Yet they are more than that. Through these we transform the material of the birch bark into a carrier of not just berries or buttons but traditional knowledge to be passed from generation to generation. In this way, waskway is not merely a resource but grandmother tree embodied.

Missed part 1? Read it here: Barking Up the Right Tree (Part 1) by Skye Haggerty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barking Up the Right Tree (Part 1)

By Skye Haggerty

This summer, RAM has two Indigenous Student Museum Interns working in various areas of the museum. Each of them has written a blog post about a project they’re creating during their time at RAM. Read the other posts here:

The Basket Tree (Part 2) by Skye Haggerty

Babies Wrapped in Love by Rogan Alexis

For many Indigenous Peoples, the availability of birch and spruce trees made their bark and roots essential materials for the creation of every-day items such as baskets. Not only is this material extremely practical, it also provides a unique medium to showcase artistic talent.

Some of my favourite memories involve going into the bush with my grandmother to collect the papery birch bark for her crafts. In the winter, I’d get to chew on spruce gum while she collected roots from the muskeg in our backyard. Sometimes these trips came with tea and cold bologna sandwiches, sometimes not, but they always included a teaching or two about Grandmother Tree and her gifts to us.

In this two-part blog post, I’ll explore the importance of these materials, the process of harvesting them, and a few of the traditional crafts my grandmother taught me to make from them.

Barking Up the Right Tree

Although there are many plants and trees available to the people of Turtle Island (North America) for basketry, the popularity of waskway (birch) as a material is a result of both the tree’s availability (it grows throughout northern boreal regions) and its unique qualities. In advance of my demonstration at the RAM National Indigenous People’s Day celebration, I recently set out with my grandmother to harvest materials to create my own basket.

The papery, flexible bark is easy to peel and harvest in the spring, May through June, and is perfect for cutting patterns. It keeps its flexibility longer than other natural materials used for traditional basketry such as nîpisîy (willow) and wîhkwaskwa (sweetgrass) with proper storage.

Birch bark is harvested in the spring months when the sap is running and the bark is at its thickest after the winter. These combined factors help the bark curl away from the tree easier and ensure that the tree will recover.

Here I am ready to harvest birch bark. First, we must give an offering to the birch tree for what we are about to take. Once that is done, we get straight to work with surprisingly few tools—just a good pen knife and a strong, steady arm!

After identifying an area of bark with little to no bumps and interruptions, a single straight cut down the side of the tree is sufficient to start the peeling. You do not want to cut too deep and strip the darker “cork” layer which allows the tree to continue circulating sap. If you peel this layer, you not only harm the tree but risk killing it. My grandmother taught me to respect the tree and this involves being a responsible harvester that looks out for its wellbeing.

Once peeled, the bark can be stored in a cool, damp environment until ready for use. It is best used within a few days, as the bark will continue to dry out and curl up.

Another traditional component for piecing the whole basket together is spruce root. Unlike synthetic sinew, once spruce root dries it keeps its shape and reinforces the basket without becoming fragile. As well, the gum of the spruce can be chewed like gum, often by children, while parents or grandparents are busy pulling the tough root from the ground.

To harvest it, you must first find a younger spruce tree. Ideally, somewhere in the six to seven foot range as their roots are less tangled and easier to pull. A spruce tree that is growing on looser soil is the best as you can clean away dirt easier. This means, of course, that muskeg is best (even with the mosquitos).

We dig around the tree to find the taproot which is thicker and will have many other roots branching off from it. From there we uncover and follow the root until we have all of it. Things can get messy and tangled pretty fast! Patience is essential so you don’t break the root off too soon while pulling.

Spruce root is typically split multiple times and can be coloured using both natural and artificial dyes. After being soaked, peeled, and split the spruce root can be used to both stitch and decorate the basket.

Now that we’ve harvested the materials, it’s time to start constructing the basket. Click the link below to read part two to learn how I’m using these pieces to craft a basket, plus learn a bit about the art of Birch Bark Biting.

The Basket Tree (Part 2) by Skye Haggerty

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

International Women’s Day 2019

Happy International Women’s Day! With so many amazing women working and volunteering at RAM, it’s hard to choose only three to profile! Today, we’d like to introduce you to Ellen Chorley, Michelle Weremczuk, and Brittney Miller.

What do you do here at RAM?

Ellen: I am an Admissions Associate, which means I am one of the first faces folks see when they come into the museum!

Michelle: I work at RAM as an exhibition designer, looking at the physical space of the gallery and thinking about how to utilize it to tell a story. My work often consists of laying out floorplans of the galleries, positioning objects in cases, drafting technical drawings for carpenters and prototyping designs before they go on the floor.

Brittney: Here at RAM, I am a bryophyte technician. The majority of my work involves dissecting and naming tiny mosses and liverworts (bryophytes) that the ABMI field technicians collect over the summer. On average, our team identify 17,000 plants annually, with over 250 unique species. Once named, the bryophytes become data ABMI uses for environmental health assessment, as well as a part of the RAM’s herbarium (PMAE) which is a resource for conservation, education, and research.

Michelle laying out 3D exhibit models

Tell us a bit about yourself and your background.

Ellen: I am a born and raised Edmontonian and my background is in theatre and writing. Along with my job at the RAM, I am have a full time job as the Festival Director of an annual multi-disciplinary arts festival for emerging artists called Nextfest (www.nextfest.ca). I also teach acting and playwriting with the Foote Theatre School at the Citadel Theatre and I am the Box Office Manager for Northern Light Theatre. Outside of my various jobs, I work as an actor, director and playwright. I was just commissioned to write a play for Vernon Barford Junior High School called “For the World to See,” and next January my play “Everybody Loves Robbie” will have its world premiere. I was named one of Avenue Magazine’s Top 40 under 40. In my spare time, I collect copies of the novel “Wuthering Heights” (I have 97 copies) and my beloved partner Pete and I have a polydactyl cat named Thumbs.

Michelle: I’ve lived in Alberta my whole life having a strong interest in art and design, and decided to pursue it in university. After graduating, I interned at the Royal Tyrrell Museum. A job was posted a few months later at the Royal Alberta Museum and I’ve been here ever since. That doesn’t stop me from getting out, though! I love going to galleries and museums whenever I have the chance.

Brittney: I started my undergraduate degree at the University of Alberta thinking I wanted to be a dentist or microbiologist. I took one introductory course on plants, realized how immensely fascinating plant research could be, and I entirely changed my direction. I completed my degree as a specialization in plant biology, and conducted research on gene expression in vascular plants, and regrowth biology of peatland and northern mosses. My work with mosses led me to fall in love with their intricate beauty and underestimated environmental significance. Following this new love, I pursued a master’s degree looking at the ability of ancient (4000 years old) Yukon moss to regrow. Through my research, I developed a passion for moss identification, which as a bryophyte technician for the RAM and ABMI I get to apply my skills and learn more every day!

Ellen dressed as Wop May on Halloween 2018

What do you enjoy about working at the Museum?

Ellen: I absolutely love working here. I think it is so special to be part of the new building. I have enjoyed meeting folks who are coming to the museum for the first time. They bring such a sense of wonder with them, and I know that there is so much to discover at the RAM! I am also a big history fan, so I love working next to galleries full of Alberta’s rich past.

Michelle: I love that everyone is so passionate about the work they do! There are so many specialists under one roof with different viewpoints, you end up learning about all sorts of things you had no idea existed.

Brittney: As I learned more about plants throughout my university career, it became important to me to be involved with evoking appreciation for how integral plants are to our existence, including moss. So to me, science, and in particular working for the museum and ABMI, is an ideal career where I could pursue a thirst for knowledge, and be a part of an organization that recognizes moss as important part of biodiversity.

I also love the emphasis RAM has on sharing knowledge and passion. Within this past year alone, I conducted plant biology lessons for elementary school students with Alberta Science Network (ASN), was a speaker for the Women in Scholarship, Engineering, Science, and Technology (WISEST) for a women and girls in nature event, and ran a workshop for Sphagnum (peat moss) identification with my coworker, Teri Hill, for the Alberta Native Plant Council (ANPC).

Brittney and a mossy friend.

What is one of the coolest things you have done in your life so far?

Ellen: I think I have had a pretty cool life, mostly because I get to work in theatre, an art form that I’m truly passionate about. I think the very coolest thing I’ve done (so far) was being in the western Canadian premiere of “Bat Boy: The Musical” in Calgary. At the beginning of the play, I had to repel from the top of the very tall set, all the way down to the stage. It was such a cool way to start the play and I loved learning how to rock climb and repel (though I always took a deep breath and crossed my fingers before I took that first leap off the set!).

Michelle: I love having pet projects, and one of my favourites is designing and laying out my garden every year. Last year I planted a LOT of cutting flowers. It is so neat to see how different plants grow and change over the summer, and I’m constantly excited to see what happens next.

Brittney: At the end of my master’s degree I had the opportunity to travel to Ellesmere Island (Canada’s North Pole) to study moss (yes, many species of moss thrive in the North Pole!). Shortly after that work, I joined the ABMI team at the RAM. The opportunity to be a part of and contribute to this world-class monitoring program has and continues to be incredible.

What advice do you have for young women today?

Ellen: I think my advice would be: Take risks. Even if you don’t get to where you thought, at least you tried — and trying is much better than not knowing!

Michelle: Find something that really interests you and go for it! You have a whole lifetime to learn.

Brittney: Passion is key. Find your passion, whether it is a field you’re interested in, or organism, or question, and say yes to any opportunity that comes your way that will allow you to purse that passion. There had been a shift in science where opportunity exists for those who have a strong work ethic, and relentless passion for knowledge, regardless of gender. And, most importantly, don’t be afraid to fail. There is an incredible amount of knowledge and growth to be gained in failure.

1 note

·

View note

Text

AND THE WINNER IS…SPRAY PAINT LICHEN!

Over 1,500 of you shared in the lichen love and voted for your favorite lichen. Of our nominees for Alberta’s emblematic lichen, the top three vote-winners were:

· Wolf Lichen (Letharia lupina)

· Vagabond Rockfrog Lichen (Xanthoparmelia camtschadalis)

· Spray Paint Lichen (also known as Candy Dot or Fairy Puke; Icmadophila ericetorum)

And the winner is… Icmadophila ericetorum or Spray Paint Lichen! This pink and green lichen won us over due to its wide appeal, ease of recognition, established taxonomy, distribution across most of Alberta, and originality amongst its fellow nominees (it’s the only crustose lichen on the list).

Sad your favorite lichen didn’t make the cut? Don’t fret - another prairie-dwelling Rockfrog was chosen to represent Saskatchewan (Xanthoparmelia chlorochroa), and there are a plethora of orange and yellow lichens nominated from other jurisdictions for all of you Wolf Lichen lovers. Have a peek at the nominees across Canada by clicking on the names below.

Thanks for participating!

· Alberta: Spray Paint Lichen (Icmadophila ericetorum)

· British Columbia: Edible Horsehair (Bryoria fremontii)

· �� Labrador: Labrador Cup Lichen (Cladonia labradorica)

· Manitoba: Golden-eye Lichen (Teloschistes chrysophthalmus)

· New Brunswick: Methuselah’s Beard Lichen (Usnea longissima)

· Newfoundland: Newfoundland Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia terrae-novae)

· Northwest Territories: Arctic Orange-bush Lichen (Teloschistes arcticus)

· Nova Scotia: Blue Felt Lichen (Pectenia plumbea)

· Nunavut: Whiteworm Lichen (Thamnolia vermicularis)

· Ontario: Powdered Sunshine (Vulpicida pinastri)

· Prince Edward Island: Maritime Sunburst lichen (Xanthoria parietina)

· Quebec: Gray Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia rangiferina)

· Saskatchewan: Tumbleweed Shield Lichen (Xanthoparmelia chlorochroa)

· Yukon: Arctic Tumbleweed (Masonhalea richardsonii)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Bizarre Case of the Jefferson’s Ground Sloth

The Jefferson’s ground sloth might be the most bizarre looking mammal to have lived in Alberta during the Quaternary Period. The Jefferson’s ground sloth, Megalonyx jeffersonii, is named after the 3rd president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, who was a proponent of early vertebrate palaeontology in North America. These sloths are distantly related to the tree sloths of Central and South America.

Bizarre Features:

- The Jefferson’s ground sloth was MUCH larger than modern sloths, growing up to three metres long!

- The Jefferson’s ground sloth’s teeth were peg-like and contained no enamel. Because of this, their teeth were soft and wore down quickly, but it wasn’t a problem because the teeth were continuously growing.

- Their large claws were helpful for grasping food in trees, and possibly for defence as well. Early sloth fossils were originally mistaken for a large tiger-like carnivore.

- The shape of their pelvis suggests they could stand on its hind legs and used their tail for added stability.

- Their hind feet were rotated, meaning they walked on the sides of their feet.

Swing by our Natural History Gallery to see how you measure up to this giant Ice Age beast in all of its bizarre glory!

https://royalalbertamuseum.ca/

0 notes

Text

International Day of Women and Girls in Science - 2019

The Royal Alberta Museum is fortunate to have many amazing women doing scientific work on our staff. As February 11 is International Day of Women and Girls in Science, we are highlighting a few members of our conservation team, who utilize scientific methods of preserving and conserving our precious objects.

We’d love for you to meet Carmen, Katherine, Genevieve and Brenna!

(Conservation team - Top: Katherine Potapova. Middle L to R: Lisa May, Carmen Li. Front L to R: Brenna Cook, Alison Fleming and Genevieve Kulis)

What do you do here at RAM?

Carmen Li

I am head of the conservation program here at RAM. The goal of the conservation program is to ensure the long term preservation of the specimens and artifacts in our collection through treatment or preventive conservation.

Katherine Potapova

I'm a paper conservator. For the most part, I repair damaged documents, maps, photographs, and other artifacts that are made of paper. Sometimes, I also help out with other conservation-related task, like preparing objects for exhibition in the galleries, and operating the equipment that we use to run tests to better understand what our artifacts are made of.

Genevieve Kulis

I am a Natural History Conservator here at the RAM. I am one of the people responsible for ensuring the ongoing care and preservation of museum’s Natural History collections. As part of this work, I get to carry out various treatments that help to repair and stabilize damaged or deteriorating specimens and objects.

Brenna Cook

I am a textile conservator. I work with textile-based objects to treat and preserve them while also preparing them for display.

What first made you interested in conservation as a career?

Carmen Li

I first heard about conservation as a career at a high school career fair, but never thought I could pursue it because of the chemistry requirements. I began studying architecture and art history, but really started reconsidering during the third year of university. I decided to follow my passion and started intensively taking first, second and third year chemistry courses in preparation for a graduate degree in art conservation. Conservation allows me to exercise both the artistic and creative side of my brain as well as the materials science part. It allows me to engage in meaningful work, and since every project is different and since we work on such a diverse collection, conservation work really is endlessly fascinating and a source for lifelong learning.

Katherine Potapova

I've always had diverse interests, and had a hard time deciding on the one thing that I wanted to pursue. In university, I was torn between fine art, history, and science. When I found out about conservation, it seemed like the perfect solution: conservators need to have skills and knowledge from all these areas. Conservators need to think systematically, like scientists. Conservators also need to understand the materials they work with on a molecular level. At the same time, they also need the creativity and craftsmanship of artists, as well as an understanding of the history of materials.

Genevieve Kulis

I have always loved museums and have found them wonderful places to learn and discover new things. Growing up, I always felt that working at a museum would be a dream come true, but didn’t know in what capacity I wanted to do that. After some research into various museum careers, I came across conservation. It had a great balance of all of the things I was interested in. It allows you to use both science and art-based skills, there is a great deal of diversity in the projects you get to work on, and it allows you to work with incredible objects and help preserve them for other people to enjoy and learn from. To me, nothing seemed to match my interests better than that.

Brenna Cook

I always had an affinity for working with textiles and a strong interest in history and material culture. I enjoyed the combination of craft and science as well as the deliberate, measured pace of work.

What was your education and career path that lead you to your current job?

Carmen Li

I pursued a bachelor’s degree in Architectural Studies and Art History, followed by a certificate in Collections Conservation and Management and then a Masters in Art Conservation. I completed internships and fellowships at the Canadian Conservation Institute, the National Museum of the American Indian, Fitzwilliam Museum, Royal Ontario Museum, and others. I coordinated a major collections move at the Museum of Northern Arizona, and then was hired as the Preventive Conservation Manager at the University of Alberta Museums which brought me to Edmonton. I joined the RAM team in 2014.

Katherine Potapova

I was halfway through a bachelor's degree in art history when I decided to try my hand at conservation. After receiving my art history degree, I went on to pursue a Master of Art Conservation degree at Queen's University. To meet the admission criteria for the conservation program, I also had to take general and organic chemistry courses, and also fine art courses, while I was finishing my art history degree.

All the conservation programs in North America are postgraduate, meaning that you need to have a degree in some other discipline to be eligible. People come to conservation from a great variety of backgrounds: fine art, history, and chemistry are some of the more common ones. Conservation is such a crossroads that skills from many different disciplines can be applicable. Everyone who wants to be successful in conservation also needs to have some knowledge outside their own discipline: a scientist needs to have some experience with art or crafts, and someone from a humanities background needs to have at least a basic knowledge of chemistry. And of course, everyone needs to be comfortable working with their hands.

Genevieve Kulis

I first attended McGill University, where I majored in Anthropology and minored in Earth and Planetary Sciences. I was fortunate enough to have a number of my classes at the University’s Redpath Museum. Having classes at the Museum allowed me to work with the collections for various lab sessions and research projects, and really solidified my interest in working at a museum. I also began volunteering there, when I could. After I graduated, I attend Fleming College for their post-graduate program in Cultural Heritage Conservation and Management. The program was really immersive and hands-on, and included a full-time internship in the final semester, which I completed at the Textile Museum of Canada. After completing my internship there, I continued to volunteer and eventually was hired on a project contract. After my contract was over, I began working as a conservator for private collectors and short-term contracts. Soon after, I found my way to the Royal Alberta Museum, where I’ve been working for the past two and a half years.

Brenna Cook

I started my post-secondary education interested in archaeology but over the course of a bachelor’s degree in the subject I discovered it wasn’t a career I wanted to pursue. I rearranged my coursework and volunteer experience to support an application to a graduate degree program in textile conservation. Following that I completed several years of internships until I secured this position at the RAM.

Tell me about some of the ways you use science in your work.

Carmen Li

The most obvious way that I use science at work is through analysis of objects or specimens. For example, we can do X-Ray Fluorescence to identify what elements are present in or on the surface objects, or we can do Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy to try to determine what an object is made of. But more generally, through an understanding of materials science, we can try predict how materials will degrade over time, how our conservation treatments would interact with original materials, and they would age over time.

Katherine Potapova

Science is really just a systematic way of figuring out what things are made of and how they work. This kind of systematic understanding is at the heart of many fields, including conservation. When working with museum artifacts, it can be very important to understand what each artifact is made of, and how these materials will behave over time. For example, some materials, like some papers and many plastics, are inherently unstable: over time, these materials often turn yellow and become very brittle. Sometimes they become so brittle that they crumble if you so much as touch them. To preserve these materials in the best conditions possible, special accommodations are needed. We wouldn’t know this without a scientific understanding of the artifacts.

When I do conservation treatments on damaged artifacts, it is also important to understand on a molecular level how the materials that I use will interact with the materials of the artifact, and how they will change over time. For example, many people who are not conservators might use sticky tape to repair tears in documents and book pages. What these people don't realize is that over time, the adhesive in most tapes undergoes a chemical reaction that causes it to turn yellow. This can happen in just a few years, although sometimes it takes 20 or 30 years. The yellowed adhesive creates an indelible yellow stain in the paper. When conservators repair tears in paper documents, they do not use tape, but rather adhesives like wheat starch paste, which have been thoroughly tested by scientists to make sure that they remain stable over time.

I have also had the opportunity to use some fairly sophisticated instruments to run tests that help to better understand the behaviour of the materials in our artifacts. For example, it is well known that many coloured materials fade when they are exposed to light for an extended time. But different materials fade at different rates. How can we know for how long we can keep a particular artifact in the light before it starts to fade? To help answer this question, we borrowed a microfade tester from the Canadian Conservation Institute. This instrument shines a narrow beam of very bright light on a very small, barely visible spot on an artifact for a specified length of time (for example, for 10 minutes). The instrument also takes repeated measurements of the colour of the spot. The computer software uses these measurements to calculate how much the spot has faded. These data can then be used to extrapolate how quickly that particular colourant would fade under regular museum lighting. I got the chance to use the microfade tester on some of our most light-sensitive artifacts, and we used the results to decide for how long these artifacts could safely be displayed in our galleries.

Genevieve Kulis

Science finds its way into my work in a number of ways. It’s a fundamental part of understanding how and why an object may be deteriorating. Understanding and identifying the types of chemical reactions that are taking place within the object itself, or between the object and something from the surrounding environment, that are causing deterioration is very important. This information informs a conservator on how to best proceed with treating the object. Science is also used during the treatment and preservation of the objects. It is important to know how an object will react with the materials being used in a treatment. Some materials or substances can be used to slow or stop types of deterioration, which can be very useful. In other instances, even just knowing what materials are safe to use with or around an object that won’t cause any adverse reactions is extremely important. Having a solid understanding of material science is quite essential.

Brenna Cook

We use scientific instruments broadly in conservation to discover information about the physical nature of materials. Most applicable to my work is our Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR) which can tell me the chemical makeup of mystery textile fibers. I also use very precise lab equipment when custom dyeing fabric as minute changes in dye stuffs, water and additives can have a great effect on the resulting colours of the fabric.

What is the coolest thing you have had the opportunity to do in your career?

Carmen Li

I’ve had the opportunity to travel and work on projects in museums and archaeological sites around the world - Canadian Arctic, Turkey, Peru, Hong Kong, UK, the Netherlands, Kosovo. All these experiences enrich my understanding of conservation of different material types, from different cultures, and in different contexts. In terms of the single coolest thing, I’ve had the opportunity to help with the installation of the Durham Cathedral’s copy of the Magna Carta when it came here to Edmonton, which was pretty special.

Katherine Potapova

Working with museum artifacts can feel pretty special. I don't really know what the "coolest" thing that I've had to do would be, but my favourite thing that I get to do is inpainting. When a photograph, poster, or some other kind of picture has scratches or cracks in it, the damage often prevents you from seeing the image properly. In that case, I sometimes paint over the scratches with watercolour paints. I do this with an extremely fine paintbrush, and I have to mix colours so that they match the colours of the area around the scratch very closely. If I'd done a good job, you would then no longer notice the scratches, unless you looked very closely. When my inpainting turns out well, I always feel like I have a kind of magical power. Suddenly the image comes together, and you see it clearly for the first time. It always amazes me what a tiny amount of well-chosen paint can do.

Genevieve Kulis

I don’t think there is a single coolest thing I’ve had the opportunity to do as a conservator. All the objects I get to work on are unique and have their own interesting set of preservation challenges. There is so much diversity in what I get to do as a conservator; I’m never bored and always excited about what I’m working on.

Brenna Cook

I’ve had the chance to get right up close to clothes that people wore hundreds of years ago, I was particularly excited to work on some French dresses from the mid-eighteenth century. You can’t get more intimate with the people of the past than that!

What is your advice to young girls interested in pursuing a career in science-related careers like conservation?

Carmen Li

Courses in science and math can lead to so many interesting and diverse career paths. Anyone can learn anything with curiosity, drive, and passion. Be fearless and follow your dreams!

Katherine Potapova

Do what interests you! Scientific thinking has applications in just about every field, not to mention everyday life. If more people had a science-based education - who knows, there might even be less nonsense in the world.

Genevieve Kulis

If you find something you’re passionate about and interested in, pursue it. Find ways to learn more about what interests you, whether that be through independent research, reaching out to someone already in the field or finding a way to volunteer in some capacity. In particular, I would say volunteering is an amazing way to get practical, hands-on experience and is a good way to find out if your area of interest is something you want to get into as a career. Even if you aren’t able to find someone in your field of interest to get in touch with, or volunteer with, immediately, don’t let that discourage you. Perseverance does pay off, so do your best to keep at it and eventually, an opportunity will come up that will allow you to get your foot through the door.

Brenna Cook

I would advise young girls to indulge their curiosity. Information is becoming more and more accessible and really digging down into a question is what science is all about!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Lichen for Alberta

Birds, stones, trees, grass… Alberta has an official emblem of each. https://www.alberta.ca/alberta-emblems.aspx

What about the humble but incredible lichen? Troy McMullin, lichenologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature, is coordinating lichen lovers in each region of Canada to nominate provincial and territorial lichens. Inspired by last year’s competition to nominate a national bird by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society (Grey Jay) this isn’t an official petition. Just a fun way of bringing awareness to the awesome lichens that inhabit Canada.

So what exactly is a lichen? You know that Spiderman character Venom, who is a symbiote between a human and an alien? They are kind of like that! Well…. Sort of… Lichens are a symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae. Together those partners transform into what we call lichens. Lichens form a myriad of shapes, colours, and sizes, and live in every natural region of Alberta. That orange stuff on trees in the city? That’s lichen. The brown ‘hair’ hanging from trees in the mountains, the bright yellow powdery lobes on logs, the tiny pyxie cups on the forest floor – all lichens!

Professional and amateur lichenologists from around Alberta have narrowed the list from the more than 1,000 species found in our province to six finalists for Alberta’s our Provincial Lichen. Learn a little about each below, then visit our Facebook page ( http://bit.ly/2RYRTH6 ) to vote for the lichen you think best represents our province!

First up!

#1

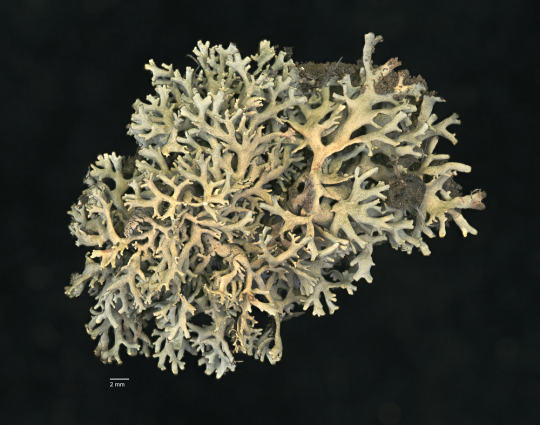

Flavopunctelia flaventior

Common Name: Speckled Greenshield Lichen

This lichen is large and leafy, minty green and lives on trees. Speckled Greenshield Lichen is the more common of two species of Flavopunctelia in Alberta. Look close for its diagnostic small white dots (called pseudocyphellae or “fake-windows”), and small patches of grainy powder (called soredia) on the surface of its lobes. The soredia are a mix of algae and fungal threads that can be carried by rain, birds or insects; if they land in the right habitat, they’ll start a new lichen. In Alberta, this lichen can be found in every natural region, including urban areas in the Parkland natural region. That doesn’t mean this lichen isn’t sensitive. Our activities decrease this species’ abundance through loss of habitat.

It grows on trees such as aspen, poplar and birch and occurs across southern Canada. It is most widespread in Canada in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Fun fact: When you touch a bit of bleach to the cottony fungal threads inside the lichen, you’ll get a pink chemical reaction, making this species great for novice lichenologists to try their hand at using chemistry for lichen identification.

Why should it be Alberta’s Provincial lichen? Its beauty, its ability to inhabit and brighten up urban parks, and its distribution across Alberta where it is limited in most other regions of Canada.

Nominated by: Darcie Thauvette, Lichenologist

#2

Letharia lupina

Common Name: Mountain Wolf Lichen

Wolf lichens (Letharia species) are bright yellow tufts that are hard to miss, especially in winter against a backdrop of snow. Wolf lichen is now understood to be two species, and, in Alberta, we have the more common Letharia lupina, whereas L. vulpina occurs further west and south. Mountain Wolf Lichen is tufted with rough branches covered in patches of grainy powder (called soredia, made of fungal threads and algae).

Mountain Wolf Lichen is an iconic montane species in Alberta, growing most abundantly in the Rocky Mountains, and Foothills. Rarely it also can be found in the southern Parkland and Grassland natural regions. It is most abundant on spruce and pine in conifer-dominated forests.

Fun fact: Or not so fun in this case. You know the old saying, don’t eat yellow….lichen!? The bright yellow colour of Wolf Lichen is from a chemical the lichen makes called vulpinic acid. This acid is poisonous. In part of Northern Europe this lichen was mixed with fat and glass shards and placed with bait to kill wolves. ‘Lupus’ is Latin for ‘wolf’. Extra extra! Scientists at the University of Alberta recently showed that Wolf Lichens are made of a team of not 1, not 2, but 3 types of fungi!

Why should it be Alberta’s Provincial lichen? Its colour and beauty, its association with the world-renowned mountains of Alberta, its limited range in most other parts of Canada, and finally its complexity - because we’re a complex and diverse province.

Nominated by Peter Josty, Executive Director, The Centre for Innovation Studies, and Mari Decker, Senior Vegetation Ecologist

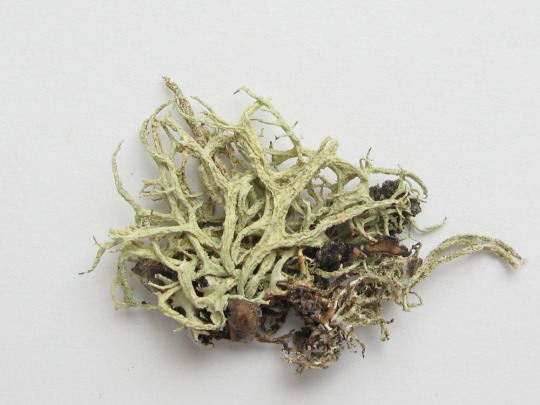

#3

Xanthoparmelia camtschadalis

Common Name: Vagabond Rockfrog Lichen

Vagabond Rockfrog is perhaps the most charismatic and elegant of Alberta’s Xanthoparmelia. Vagabond Rockfrog typically is toonie sized, forming larger colonies when the site is right. Its lobes are slender and evenly branching; its colour is pale greenish yellow with white mottling, almost as if it was sponge-painted with watery, white paint. Keep your eyes on the ground in a prairie or well-managed pasture, and you’ll usually find this lovely lichen loosely attached to soil or resting on top of Prairie Selaginella (Selaginella densa) and Pixie-cup lichens (Cladonia spp.).

Vagabond Rockfrog Lichen is most common in the Grassland natural region but also can be found in the Rocky Mountain region. In Canada it appears to be most common in our province, with additional collections from Saskatchewan or more rarely British Columbia.

Fun fact: This lichen got its Latin name from the region it was first described from, Kamchatka, Russia. It is part of a living soil crust community that fixes carbon and nitrogen from the air, stabilizes soil, helps absorb water, and perhaps even forms a barrier to some invasive weeds.

Why should it be Alberta’s Provincial lichen? Its beauty, its association with the historically and economically important grasslands of Alberta (Alberta beef anyone?), and its limited range in other parts of Canada. Most Albertans live and work in the natural regions that historically supported prairie and aspen forest mosaics, the Grassland and Parkland. Provincially, native grassland has declined, which has also reduced quality habitat for grassland lichens. Grassland lichens are under-appreciated and under-studied - choosing a grassland ambassador could raise awareness.

Nominated by Lysandra Pyle, Rangeland Ecologist

#4

Melanelixia albertana

Common Name: Powdered Camouflage Lichen

First described from Alberta 50 years ago, Melanelixia albertana shares our province’s name. Melanelixia albertana is not in-your-face, and tends to camouflage with its olive-green color. Look on deciduous tree bark, especially poplar trees, for a leafy lichen 4 to 10 cm wide with rounded lobes and little white powdery ‘lips’ (called soralia). The skin of Powdered Camouflage Lichen is often shiny, almost oily, in appearance.

Powdered Camouflage Lichen is found in every natural region of Alberta, most commonly in the Boreal and Parkland. But don’t worry about going far to get a look; Melanelixia albertana can be spotted in urban centres, including Edmonton’s river valley. Within Canada, Melanelixia albertana is limited to the west with most collections found in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Definitely, something to brag about to your friends out east!

Why should it be Alberta’s Provincial lichen? Ok – it’s not yellow. But beauty is in the eye of the beholder, right! This species is named for Alberta, and current data suggests it is more abundant in Alberta than anywhere else in the world. The ‘smelly Melies’ are typically a genus of hard-to-identify brown leaf-like lichens. But Powdered Camouflage Lichen makes it easy (sort of) with its lip-shaped soralia - just like Alberta, it is unique amongst its compatriots. And finally, there’s that oily sheen – need we say more?

Nominated by Laura Hjartarson, BSc, and Derek Johnson, Botanist & Forest Ecologist

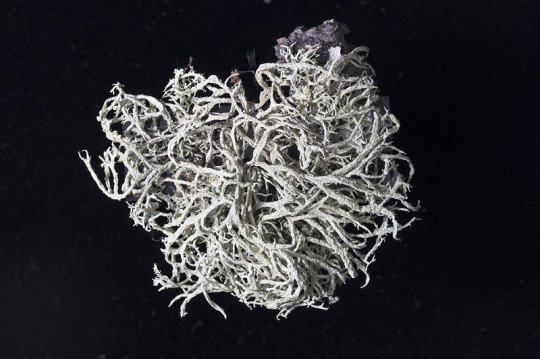

#5

Evernia mesomorpha

Common Name: Boreal Oakmoss Lichen

Picture Einstein’s hair – only greener and thicker - that’s Boreal Oakmoss Lichen. Pale greenish-yellow, tufted and shrubby species, this lichen is found on trees of all sorts in sunny forests throughout Alberta.

Boreal Oakmoss occurs in every natural region of Alberta, most commonly in the Boreal and Foothills forested regions. However, it is a hardy species and will pop up in the grasslands on soil, rocks and fence posts.

Fun fact: This lichen has a long history of human use, particularly in Europe where thousands of tons of Evernia are collected and ground up as a perfume fixative (while it is abundant here, it’s not abundant enough to do that in Alberta!). It is also tolerant of people, and while most shrubby lichens struggle in the city, Boreal Oakmoss Lichen can be found in Alberta’s urban river valley parks.

Why should it be Alberta’s Provincial lichen? This is a hardy northern species (like Albertans) that thrives across much of Canada. However, it prefers Alberta to British Columbia and its range is mostly restricted to east of the Rocky Mountains.

Nominated by Sandra Davis, Botanist

#6

Icmadophila ericetorum

Common Name: Spray Paint Lichen

Spray Paint Lichen is aptly named – it’s easily recognized as a splash of mint green dotted with pink ‘buttons’ (actually the spore-bearing structures, called apothecia, of the lichen). Spray Paint Lichen is a crust lichen, that is, its ‘body’ is limited to a thin layer of algae and hyphae growing intimately attached to whatever it is growing on.

Spray Paint Lichen grows on damp moss, rotted wood and soil, and can be found in every natural region of Alberta. It is most common in the mountains and bogs of northern Alberta.

Fun fact: This lichen has a few common names, including Candy Dot and (ahem) Fairy Puke. No matter what you call it, this lichen is a showstopper.

Why should it be Alberta’s Provincial lichen? This is a fun, charismatic crustose lichen that is easy to identify and occurs across much of Alberta. It also draws attention to two of our iconic environments, the Rocky Mountains, and the bogs of northern Alberta that play a critical role in water retention and filtration. It is also the only species of the genus found in North America.

Nominated by Derek Johnson, Botanist & Forest Ecologist, and Diane Haughland, Lichenologist

Pretty cool huh?

Update: Jan 29, 2019 - Voting closed on January 27th, but keep an eye on our Facebook ( http://bit.ly/2RYRTH6 ) page for an announcement of the winner!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmases Past

by Julia Petrov, Curator of Western Canadian History

Children’s toys were often made to prepare boys and girls for their future roles. Let’s see what the ghosts of Christmas Future foretold for a few Albertan children in the 1920s and 1930s.

One lucky Alberta boy named John Scott Livingstone had a loving aunt who spoiled him and his brother and sister with presents. John’s mother was a widow, but her sister worked as a nurse, and made sure that her nephews and niece had presents every Christmas. As John lived on a farm in Olds and his aunt lived in Calgary, she purchased the presents through the Eaton’s catalogue – much like we order gifts online today!

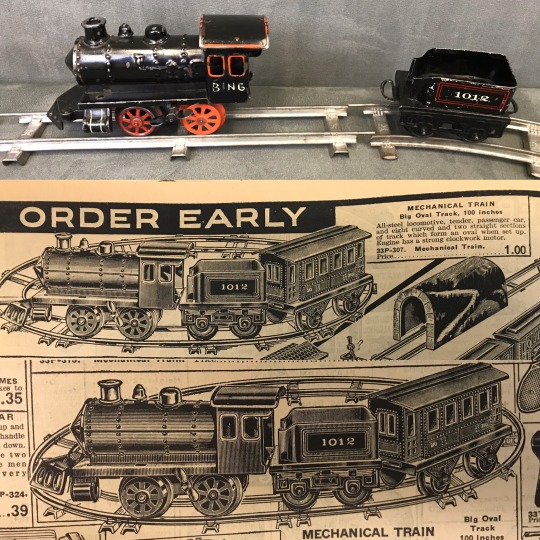

This toy locomotive set retailed for $1.00 in the 1925-26 catalogue, about $15.00 today. It came in a large box, which was left at the foot of his bed by Santa Claus on Christmas morning. The donor and later, his children, obviously loved playing with it, because the passenger car has since been lost.

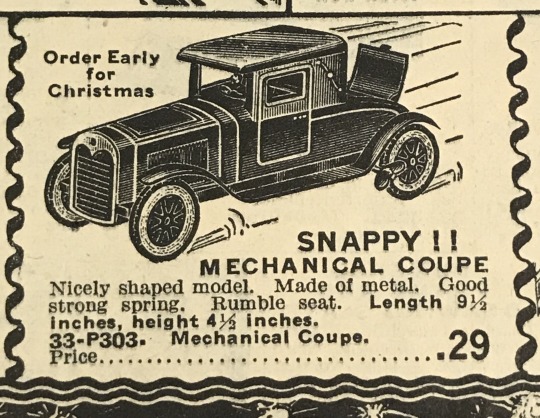

This sporty red Packard coupe car could be made to race when a key wound up the clockwork mechanism inside.

This Louis Marx & Co. wind-up tractor originally came with a figure of a farmer. Aunt Kathleen would have paid the equivalent of about $10.00 for it in around 1931. John loved to play with it on top of his mother’s ironing board. Tractors would have been a familiar sight around the area.

This German-made wind-up toy plane, which retailed for $1.00 in 1923 but only $0.50 by 1925, was so well-loved that John took it to an instructor at NAIT to make replacement parts. The propeller and wings move when the key winds the coiled spring inside.

Interactive mechanical toys were popular gifts marketed towards boys interested in engineering. Eaton’s sold several different kinds of steam engine models in the 20s and 30s. John must have learned his lesson well, because after he moved to Edmonton in the late 1940s, he worked for the natural gas provider Northwestern Utilities.

Jessica Hanna’s father managed the Edmonton Hudson’s Bay store, so he was able to purchase this expensive German porcelain doll and premium wicker doll carriage for her in 1922, when she was just 4 years old. In today’s prices, this gift would be worth around $200! The doll’s name was Marjory, and both her original hair and clothing have since been lost; the doll’s wig was replaced with Jessica’s own baby hair. Marjory’s realistic face and fully-jointed body made her a miniature baby. The carriage was also a smaller replica of popular models for real babies at the time. Jessica obviously enjoyed learning caregiving, because she served as a nurse in England and Belgium during the Second World War, and was one of the founders of the Women's Emergency Shelter and WIN House.

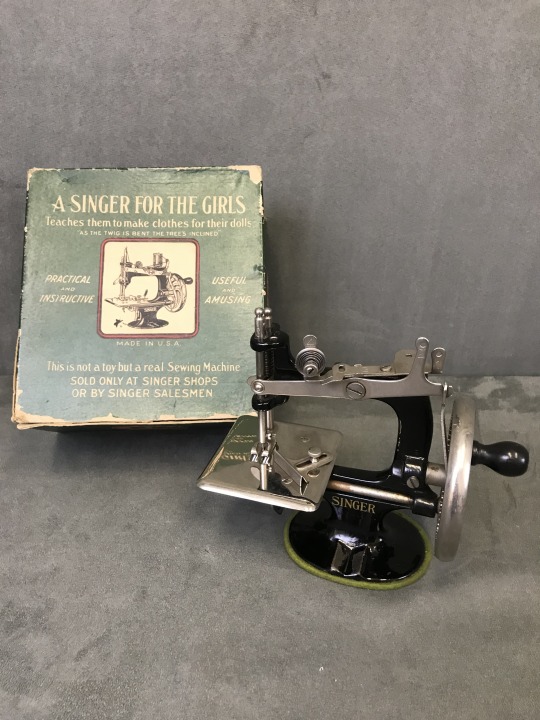

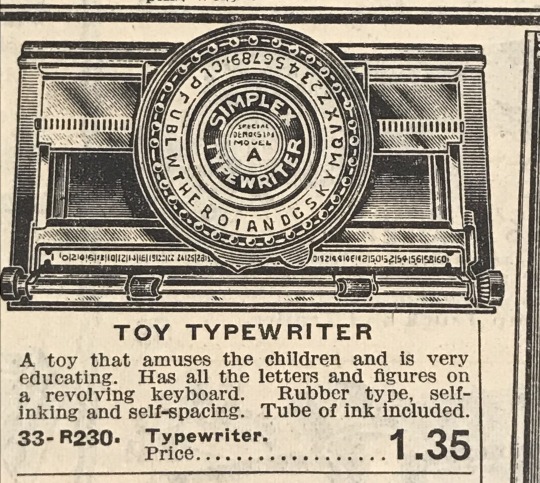

Maxine McLeod Harrison had a great Christmas in 1935, when she was given these toys. Maxine learned to sew on this miniature machine, which was bought at the Singer store on Jasper Avenue, and made clothes for her dolls, just like her mother made clothes for Maxine on her full-size Singer sewing machine. Maxine also enjoyed playing with the Gunthermann typewriter for several years until she was 11 or 12 years old. Typing was a useful skill for girls, many of whom would become administrative assistants in offices, stores, or factories, as Maxine herself did when she grew up.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Over By Christmas

by Julia Petrov, Curator of Western Canadian History

It’s Christmas morning on a farm near Neepawa, Manitoba in 1915. A boy named Thomas Watson is opening his presents. He lifts the lid on the box, and peels back the paper liner; it has words in French, “couleurs sans danger”. This present came from far away! Inside are four toy soldiers, hand-painted with red tunics and spiked black helmets. Thomas recognizes them as British troops from the Boer War. Their uniforms are much more exciting than the khaki ones given to the young men who enlist in his town. http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/sites/neepawawarmemorial.shtml

All his school friends are going to be so jealous of these toys! His mother says they were ordered by mail all the way from Winnipeg! Thomas has seen this year’s Eaton’s Christmas catalogue, and counted no less than 14 soldier- and army-themed toys. He’s sure his pals will get some, too.

Everyone is talking about the war in Europe, although they are sad, too. Everyone thought it would be over by Christmas 1914, but it’s been another whole year. Thomas has heard that the Canadian boys are being very brave, and helping to beat the Germans at Ypres, but a few from his district have already been killed at the front. There’s lots of songs about the war, too, and Thomas has heard the most popular ones of the year: "Till the Boys Come Home (Keep the Home Fires Burning)", "Laddie in Khaki", and "Tim Rooney's at the Fightin'".

Thomas hums some of the songs as he plays with the soldier figurines. He loves the toys so much that he keeps them with him when he and his new wife move to Wembley, Alberta in 1925, and even when he’s retired and living in Edmonton in the 1960s. He only offers them to the new provincial museum in 1969 because he has to move to a new house and has no more room for them. Now they help Albertans remember days of Christmas past.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of RAM

Take a look at some of the milestones the Royal Alberta Museum achieved over the years.

The Carillon Room

Many do not know that the museum’s beginnings were rather humble: one small room in the Alberta Legislature known as the Carillon Room. Prior to 1967, this room at the Leg was used as the provincial museum.

The Plans to Build and the Opening

Planning for the museum had begun in the 1950s, but a museum professional was not hired to guide the project until 1962. In 1964, federal funding and matching provincial funds were announced and Raymond O. Harrison, an Australian, was hired and given five million dollars and three years to find a site, construct a museum, hire staff, build collections, and prepare exhibits to fill 4000 square metres.

The RAM opened to the public on December 6, 1967 under its original name: The Provincial Museum of Alberta. On the museum's opening day, visitors were introduced to three main floor galleries: Fur Trade, Native Peoples of Alberta and early photographs of Aboriginal people taken by Ernest Brown and Harry Pollard. Second-floor galleries focused on Agriculture, Pioneer Life and Industry and Commerce.

Sweet home Glenora

The museum expanded continuously throughout the 60s, 70s, and 80s, adding a range of curatorial programs and staff. The Friends of Royal Alberta Museum (FRAMS) Society was formed in the 1980s. FRAMS continues to operate today and its volunteers provide invaluable support to the museum through fundraising, and assisting with public and school programs and collection acquisitions.

During the 1990s the museum's management team decided upon a radical shift in programming with a concerted effort to increase its audience. The ground floor Indian Gallery was dismantled to create a large feature exhibition space. Over the next dozen years (from 1989 to 2001), the museum embarked on an ambitious program of feature exhibitions - some travelling from other museums across North America, others entailing collaborative ventures coordinated by the museum - that brought extraordinary collections from across North America, Europe and Asia. In all, more than 175 exhibitions were presented.

Behind-the-scenes, the museum's curatorial section continued to grow and evolve from Human History and Natural History into 13 separate programs of study including: Archaeology, Botany, Cultural Studies, Ethnology, Geology, Ichthyology, Invertebrate Zoology, Mammalogy, Military and Government History, Ornithology, Quaternary Environments, Quaternary Palaeontology and Western Canadian History.

In 2005, the museum was renamed the “Royal Alberta Museum” in honour of Queen Elizabeth II, who visited Alberta that spring.

Deciding to build a new museum

On April 6, 2011, then Premier Ed Stelmach announced that a new Royal Alberta Museum would be built in downtown Edmonton. An international design-build competition was launched, ultimately attracting high international interest, including submissions from two Pritzker Architecture Prize-winning architects. In the end, the project was awarded to a local team, Ledcor Design Build (Alberta), which included the architectural firm, DIALOG.

Saying Goodbye to Glenora

On December 4-6, 2015 the museum hosted one of its most ambitious events yet: a 48-hour closing party to celebrate 48 years of RAM. Nearly 36,000 people came out to visit the Glenora galleries one last time before they were closed permanently for the move downtown. Thousands of museum memories were shared with staff during that weekend – adding to the exciting possibility of many more thousands waiting to be made in the new space downtown.

Moving downtown

The museum move proved to be a mammoth undertaking that required time and specialization. Aside from moving millions of artifacts, staff dedicated countless hours to developing new galleries, multimedia and stories that aim to inspire and educate visitors. In 2016 construction of the building was completed, marking the beginning of gallery development: building the hundreds of exhibits that cover over 25,000 years of Alberta history. And, of course, preparing for the day we open the doors.

Opening day

The new Royal Alberta Museum officially opened its doors to the public on October 3, 2018.

After years of construction, moving millions of objects, creating new galleries, installing exhibits and putting on finishing touches, RAM welcomed its first visitors in its new location. For the first six days, visitors could explore their provincial museum free of charge. More than 41,000 people visited during those six days.

More than 5,300 objects are featured in a variety of galleries. The new Natural History Hall celebrates the wonders and diversity of the living world, from the tiniest lichens to the mighty mammoths that once roamed the province. The Human History Hall shares compelling stories of who we are, from the earliest people to the Albertans of today. The experience is rounded out by the new Bug Gallery featuring live invertebrates, a 2,130-square-metre (7,000-square-foot) Children’s Gallery, and a state-of-the-art feature gallery space that will host international exhibitions, alongside a museum shop, café and theatre space.

The new galleries share more of the countless treasures and stories in the museum’s care, offering visitors a better understanding of what epitomizes Alberta. Objects collected by the museum over the past 50 years are central to the exhibits, and the stories they reveal offer insights into the people, places and processes that have shaped Alberta.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Mystery of the Ghost Bride

Did you know that Alberta’s own legendary Banff Springs Hotel is famously haunted? Many stories have been told about its spectral inhabitants, but now, the Royal Alberta Museum has a real piece of its ghostly past.

We were recently contacted by a scrap metal dealer in Calgary, who told us that in the 1980s, she and her husband disposed of a large amount of material from the Hotel when it was undergoing renovations. Lengths of ornate cast iron left in a field caught her eye for their craftsmanship and quality, but she was amazed to hear that they were actually the railings from the staircase which was demolished after a young woman lost her life on it.

The story goes that sometime in the 1920s, a young woman was descending the stairs on her way to her wedding banquet when her beautiful white veil caught fire on the sconces that illuminated her way. Panicked, she tripped and tumbled down the marble stairs to her doom. The hotel walled off the staircase for safety, and later demolished it all together. The iron and brass railings were left to rust in a field behind the hotel for decades, while the unfortunate bride went on to frighten hotel guests who caught a glimpse of her ghost in a white dress floating down corridors late at night.

This story has been published in several books, appeared in television shows about hauntings across Canada, and is the subject of ghost tours around the Hotel. [https://calgaryherald.com/life/food/ghosts-and-guests-mingle-at-haunted-hotel-themed-events-at-the-banff-springs-hotel] There is even a series of Canada Post stamps featuring an image of the ghost bride of Banff Springs.

The stamp set also includes a coin with a spooky hologram of the same image.

The Calgary scrap metal dealer was also taken with this story, and saved these railings in her own backyard for twenty years, before agreeing to donate them to the museum. Some of you may recognize the design: it is identical to the railing that leads down from the Hotel’s Cascade Ballroom, which is the oldest surviving part of the hotel, dating from about 1914.

Tom Wilson and First Nations chiefs, Banff Springs Hotel, Banff, Alberta, 1924, Glenbow Museum, NA-15-4

The rest of the building was destroyed in a fire that started on April 17, 1926, and had to be rebuilt, with new materials. Did the ghost bride cause the fire? Is there a real ghost that haunts the hotel?

It’s true that there was a catastrophic fire that caused years of rebuilding and renovations. It’s also true that many couples did get married or honeymoon in the Hotel. It’s even true that a young woman once fell down some stairs in Banff (although that was in 1931, and not in the hotel – Miss Margaret Batten, a sightseer from Seattle, suffered a head injury after a railing in Johnston Canyon gave way, but she was not killed).

There is no evidence that any brides ever perished at the hotel. In fact, the earliest mentions of this ghost story come from the late 1980s, the same time that our donor was told the tale.

So where did the story come from?

As early as 1922, tour guides in the National Parks were inventing stories to amuse locals. One nicknamed Nifty apparently made up a ghost story for the Chateau Lake Louise:

The Haunted Ghost "Nifty" is memorizing a truly wonderful story regarding the haunted chamber at Lake Louise Chateau, with which he will regale tourists the coming summer. According to-"Nifty's" version a beautiful young woman slipped on a wet stone while wandering around Lake Agnes, out of the "Lakes in the Clouds," and rolled to the bottom of the mountain side. When found her spirit had fled, but it is said to still inhabit her room at the chateau and not even the spirits of Johnny Walker or Peter Dawson can drive it hence. It is a most thrilling tale as depicted by the volatile carriage agent at the King Edward hotel.

The Crag and Canyon, May 20, 1922 (University of Calgary Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections)

In addition, with the ever-increasing popularity of the hotel, constant renovations were occurring, leading to some strange architectural features. In what is now called the Bow Valley Grill, seasonal restaurant staff were spooked by a blocked-off staircase in the middle of the restaurant. It is probably this staircase, which was eventually removed, that is the source of the railing recently donated to the museum.

A skeptic might say that very real historical facts were combined to make a tall tale to attract even more tourists to the mountain landmark. But we’re keeping an eye out for ghostly goings-on around the railing at our storage facility, just in case!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Unexpected Partnership

By Kelsie Tetreau, Communications Officer

What happens when you combine the RCMP Explosives Disposal Unit, X-ray machines, and priceless historical artifacts? Read on to find out!

An X-ray of a shoe from our Western Canadian History Collection

Our day-to-day work may look very different, but it turns out that RAM conservation staff and RCMP Explosives Disposal Unit share a similar need: the need to X-ray things!

The RCMP Explosives Disposal Unit uses X-rays to help their technicians determine if a suspicious package poses a threat or not. The RCMP recently acquired new portable X-ray equipment that minimizes the number of times a bomb technician must go near the suspicious package, which of course, is safer for the bomb technician.

We know what you’re probably thinking: That makes sense… but why does the museum need to X-ray bombs?

Well, it’s not bombs that we need to see inside, but artifacts. As we prepare artifacts for install in our new galleries, we need to figure out how best to mount them. But for some artifacts, we aren’t able to tell how sturdy an object is, or what kind of material it’s made out of by simply looking at it. As the saying goes, it’s what’s inside that counts.

Riley being X-rayed by the RCMP Explosives Disposal Unit’s new equipment

For example, our friend Riley the Horse, who we recently acquired after he stood out front of the Riley & McCormick store in Calgary for decades. While preparing Riley for installation in the gallery, we wanted to be sure that he would be sturdy enough to stand for years to come. Unfortunately, from simply looking at him from the outside, it is impossible for us to know exactly how his legs are connected to his body, and if they will hold up over time. That is, without performing artifact surgery and taking him apart.

This is where the partnership begins: The RCMP Explosives Disposal Unit needed to train their technicians on this new equipment and we needed to know more about what is holding our artifacts together.

Two RCMP officers brought their portable X-ray machine to the museum and X-rayed Riley, a classic shoe, and an old saddle. It’s fascinating to see the many materials that keep these artifacts together. We also discovered that Riley is more than sturdy enough to stand in our galleries. Check out all those nails keeping him together!

Thanks to the RCMP for helping us learn a bit more about our artifacts!

Looking sturdy! An X-ray of Riley’s legs show his legs are super reinforced.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating Contemporary Indigenous Fashion

To celebrate National Indigenous Peoples Day, we’re highlighting three contemporary Indigenous fashion designers whose work you’ll be able to see featured in the Human History Hall of the new Royal Alberta Museum when we open later this year!

Derek Jagodzinsky

The creative mind behind Edmonton-based fashion house Luxx designs clothing that is sleek, modern, and effortlessly chic. Jagodzinsky draws on his Cree heritage to “push boundaries by fusing traditionally inspired art with modern shapes and technological innovations”.

Derek Jagodzinsky at one of his fashion shows

Cree syllabics reading ‘We Will Succeed’ are transformed into bold patterns in this dress and matching clutch from Luxx’s Spring/Summer 2014 collection Four Directions. Jagodzinsky draws on the work of other Indigenous artists, frequently featuring beadwork by women of his home community of Whitefish Lake First Nation.

Dress and clutch from Jagodzinsky’s Four Directions collection

In 2015 Jagodzinsky collaborated with Indigenous artist and Edmonton city councillor Aaron Paquette to “honour the creativity and beauty of [our] culture”. The shirt, from The Strength of My Nation collection, incorporates Paquette’s painting of a strong Indigenous warrior woman.

Shirt from Jagodzinsky’s The Strength of my Nation collection

Albertine Crow Shoe

“I create a style of jewelry that reaches back into history. My designs form a contemporary connection to traditional Blackfoot culture. I use materials to explore the history and spiritual power of my people.” –Albertine Crow Shoe

Albertine Crow Shoe in her Bull Plume Studio.