Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

This is such an incredible and through analysis of Love and Basketball. Your breakdown of Monica's character and how she embodies Judith Butler's concept of gender performativity is excellent. Do you think the film offers any contrasting portrayals of femininity through other characters, or is Monica the sole focus on gender performance?

Critical Film Analysis: Love & Basketball

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1xmTgozILMEuBzjrQlRwJGVPjhmLKjrX_/view?usp=drivesdk

Love and Basketball chronicles the intertwined lives of Monica and Quincy across four distinctive periods. Their childhood friendship rooted in basketball becomes complicated when Quincy accidentally injures Monica, leading to a rollercoaster of emotions but ultimately forging a deep connection. As teenagers, they navigate high school life, with Quincy's popularity and Monica's basketball prowess setting the stage for a budding romance that endures despite challenges. Their college years bring individual struggles: Quincy grapples with media scrutiny and family issues while Monica contends with coach conflicts, straining their relationship to a breaking point. Fast forward to their professional basketball careers, Monica playing overseas and Quincy in the NBA. A pivotal moment arises when Quincy faces an injury and impending marriage, prompting Monica to confront her past and chart a new course. Their love ultimately triumphs, sealed by a high-stakes basketball game, leading to marriage, parenthood, and Monica's eventual achievement in the WNBA, symbolizing their enduring connection through their daughter's love for the game in the post-credits scene.

Monica's character in Love and Basketball serves as a powerful canvas for examining Judith Butler's concept of gender performativity. Her journey and passion for basketball intricately challenge and redefine traditional gender roles, offering a profound exploration of performative gender within the film. Butler argues that “hegemonic heterosexuality is itself a constant and repeated effort to imitate its own idealizations” (338), meaning that our prescribed ideas of gender only come about through enforced stereotypes and expectations, rather than being predetermined ideas. In this way, Monica breaks the mold of predetermined ideas of both masculinity and femininity.

From a young age, Monica exhibits a profound affinity for basketball, a sport traditionally associated with masculinity. Her natural talent, determination, and passion for the game become the cornerstone of her identity, highlighting how her engagement in this particular activity challenges the conventional expectations of femininity.

Monica's embodiment of athleticism disrupts the societal notion that certain sports are inherently masculine. She defies the prescribed boundaries of what it means to be a girl by embracing basketball wholeheartedly, showcasing physical prowess and competitiveness commonly attributed to masculinity. Her performance in the realm of basketball not only challenges but reconfigures the boundaries of gendered activities, exposing the fluidity and constructed nature of gender roles.

Throughout the film, Monica's dedication to basketball blurs the lines between conventional notions of femininity and masculinity. She navigates the basketball court with skill and determination, not conforming to the passive image often associated with women in mainstream media. Instead, Monica actively challenges this notion, illustrating that gender identity is not predetermined but rather shaped through actions and performances.

The concept of performative gender is vividly demonstrated in Monica's actions, which defy societal expectations and challenge the status quo. Her passion for basketball becomes a platform for the reimagining of gender norms, prompting audiences to reconsider the limitations imposed by societal constructs.

Furthermore, Monica's embodiment of performative gender extends beyond her actions on the court. Her refusal to adhere to traditional gender roles within romantic relationships and her unwavering commitment to her career aspirations exhibit a deliberate performance that transcends prescribed gender norms.

In essence, Monica's character in Love and Basketball becomes an embodiment of Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity. Her passionate engagement with basketball challenges and reshapes traditional gender roles, presenting a compelling narrative that questions the rigidity of societal expectations surrounding femininity and masculinity. Through Monica's journey, the film invites audiences to reconsider the performative nature of gender and the fluidity inherent in its expression.

Monica's bold defiance of traditional gender roles, intricately explored within the film's narrative, segues seamlessly into the broader exploration of societal stereotypes through character portrayals, aligning with Stuart Hall's reception theory and the film's approach to challenging norms. While Monica's passionate engagement in basketball serves as a catalyst for questioning and reshaping gender norms, the subsequent narrative unfolds, compelling audiences to reconsider ingrained societal stereotypes, encouraging critical decoding of these moments, and fostering a more inclusive understanding of gender dynamics and relationships.

Love and Basketball consistently challenges societal stereotypes through its narrative and character portrayals, aligning with Stuart Hall's reception theory about decoding media messages. Several instances stand out, prompting audiences to resist or reshape prevalent societal norms. By operating within the basketball realm, which is often a male-dominated space, while empowering Monica, the film “acknowledges the legitimacy of hegemonic definitions to make the grand significations (abstract), while, at a more restricted, situational (situated) level, it makes its own ground rules” (Hall, 516).

One poignant example is Monica's rejection of the 'damsel in distress' trope within romantic relationships. Unlike conventional portrayals of women waiting for men to define their lives, Monica asserts her agency in shaping her destiny, refusing to conform to the passive roles often depicted in mainstream media. Her determination to prioritize her career aspirations over conforming to traditional gender roles challenges the audience's expectation of female characters, inviting them to decode this rejection as a departure from typical gender norms.

Moreover, the film subverts the stereotype of women as mere objects of desire by presenting Monica as a multifaceted character. Rather than being reduced to a passive love interest, Monica's character is layered, showcasing her emotional depth, ambition, and imperfections. Audiences decoding these nuances witness a departure from the traditional male-centric gaze, reshaping the perception of female characters in cinema.

Additionally, the film challenges the stereotype that sports are exclusively a male domain. Monica's journey in pursuing basketball as a career confronts the societal notion that certain sports are inherently masculine. By showcasing her athleticism, competitiveness, and love for the game, the film defies the notion that women are less capable in sports, prompting audiences to decode these moments as a challenge to gendered stereotypes in athletic pursuits.

Furthermore, the depiction of Monica's and Quincy's relationship resists conventional gendered dynamics. The film portrays emotional vulnerability in Quincy's character, breaking the stereotype of male emotional detachment. Monica and Quincy's relationship evolves beyond the constraints of traditional gender roles, inviting audiences to decode these nuanced interactions as a reimagining of relationships that transcend societal expectations.

Moving from the film's challenge to societal norms through characters to its portrayal methods, Love and Basketball offers a complex view. It tackles gender expectations while following Monica's journey, challenging traditional movie ideas about gender and romance. This allows for a detailed look at both its social messages and its approach to moviemaking, going beyond usual portrayals in mainstream cinema.

The film intricately navigates the male gaze in its portrayal of Monica's athletic prowess and romantic interactions, employing cinematography that both aligns with and challenges traditional conventions. When showcasing Monica's basketball skills, scenes often focus on her agility and dedication without overt objectification. For instance, in the basketball court sequences, the camera skillfully captures Monica's movements, emphasizing her talent and determination. During pivotal basketball moments, such as her winning shot, the camera follows her actions, highlighting her skill without reducing her to a mere object for the male viewer's gaze. This deliberate framing invites the audience to appreciate Monica's athletic abilities and passion for the game without exploiting her physicality.

Conversely, in romantic interactions, the film occasionally aligns with elements of the male gaze seen in traditional cinematic tropes. For instance, during intimate moments between Monica and Quincy, certain scenes utilize close-ups and framing that could cater to a male-centered perspective. However, the film also subverts these norms by ensuring Monica's character maintains agency and complexity within the narrative. In moments where Monica navigates her romantic relationship, the storytelling consistently portrays her as an individual with desires, emotions, and aspirations, transcending the traditional objectification often associated with the male gaze in cinematic portrayals of women. For example, the scene where Monica confronts Quincy about his infidelity portrays her emotional depth and agency, shifting the focus from mere objectification to a complex depiction of her feelings and choices within the relationship.

Overall, the film carefully balances between conforming to and challenging aspects of the male gaze. Through specific examples in cinematography and narrative framing, the film acknowledges prevalent cinematic tropes while also presenting Monica's character with depth, agency, and emotional complexity. The deliberate portrayal of Monica's athletic talent without excessive objectification and the nuanced handling of her romantic interactions contribute to a layered depiction that both engages with and transcends elements of the male gaze prevalent in cinematic storytelling.

Love and Basketball skillfully encapsulates Monica's profound evolution from a spirited young girl to a resolute athlete, challenging rigid gender expectations and redefining societal norms. Her ardent pursuit of basketball, intertwined with her resilience against conventional standards, serves as a beacon, reshaping perceptions of athleticism and established gender roles. Throughout the narrative, the film carefully delves into Monica's character, granting her a multifaceted portrayal brimming with depth and autonomy. Concurrently, her relationship with Quincy forms an evocative canvas that subverts traditional gender dynamics. The movie beckons audiences to engage critically with its compelling storyline, urging contemplation on nuanced portrayals that disrupt and reconstruct prevalent stereotypes. Monica's unwavering commitment to basketball and her intricate romantic journey within Love and Basketball serve as a powerful commentary, challenging societal norms while meticulously navigating between conforming to and diverging from cinematic conventions. This intricate dance within the film's narrative fabric transcends conventional gender depictions, carving an indelible mark in the realm of mainstream cinema with its layered and authentic portrayal of a woman's journey through sport, love, and self-discovery.

Citations:

Butler, Judith. “Gender Is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion.” Taylor & Francis, September 3, 2014. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/mono/10.4324/9780203760079-5/gender-burning-questions-appropriation-subversion-judith-butler.

Hall, Stuart. “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse.” Semantic Scholar, September 1, 1973. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Encoding-and-Decoding-in-the-television-discourse-Hall/9d8d680436345535ae2598f9e6786c68d4143f9b.

Love & Basketball Directed by Gina Prince-Blythewood, performances by Sanaa Lathan and Omar Epps, 2000.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have never seen this film but I am intrigued to watch it as I am looking for some more films that have good queer representation and this seems like the perfect option. It seems sweet and sensitive but yet not to cringey.

Pariah - Dee Rees (2011)

Engaging with film and media gives the public an opportunity to get to know people, places, and identities that they wouldn’t necessarily encounter in their own lives. Because of this, there are great steaks in the way that we represent people, particularly those who have been oversimplified, minimized or left out of stories completely. There are hugely necessary conversations happening about representation in film, the goal being to humanize people and refrain from perpetuating negative stereotypes that hold back representational progress. But what do we mean when we say “positive representation” and “positive imagery”? Do stereotypes always equate to negative representation? Dee Lee’s 2011 film Pariah breaks down some of the rules we have created about representation and shows us characters that expand stereotypes rather than rejecting them completely.

Pariah tells the story of 17 year old Alike coming to terms with her lesbian identity, navigating her queerness in the world of high school dating as well as in her religious and homophobic household. Alike’s best friend Laura – butch, sexy, confident, and much more romantically and sexually experienced than Alike – is attempting to help Alike break out of her shell and meet someone. Laura has not spoken to her mother in months and is living with her sister, working to support them, and attempting to get her GED so she can take on more responsibility. I find Laura’s story and her friendship with Alike to be really compelling and significant surrounding conversations of queer representation. Laura and Alike’s friendship is perfectly balanced with tenderness and tough love. When Alike decides that getting a strap-on would benefit her “image”, she goes to Laura and asks her to get one for her. Laura lovingly laughs at Alike and without question agrees to help. They stand together in the mirror as Alike reluctantly tries it on, Laura cheering her on and reassuring her that she looks good. There is something that is very sweet about this moment, evoking the innocence of a coming-of-age friendship, awkwardly helping each other navigate the constant newness and uncharted territory of their teenage lives. We continue to see moments like this where Laura and Alike, who are both forced to harden themselves to manage the intensity of their family lives, soften up with each other. When Alike starts having a romantic relationship with Bina, a neighborhood girl who her mom forces her to start hanging out with to keep her from Laura, Laura comes to Alike with concern about drifting apart. She tells Alike, “I just want to get this off my chest. I’m glad she makes you happy. I’m happy for you. Cause I love you.” You can tell on Alike’s face that she is shocked to hear this. You can see on Laura’s face that this kind of expression is difficult for her. The real turning point in our understanding of Laura is the first time we meet her mom. Laura comes to see her and nervously attempts to get everything out. She tells her she got her GED and that her and her sister are working hard and making her proud. Her mother says nothing before shutting the door and going back inside. This is a really significant moment for Laura because up until this point she has never seemed to care what anyone thought of her. We realize here that there is one person who she will always be trying to impress. She stands outside her mothers door panicked and in tears. All she wanted was her recognition and approval.

I think a lot of concerns around queer representation frame the existence of stereotypes as inherently negative, fighting for queer characters who are doing something different. In his book, Female Masculinity, Jack Halberstam questions what we really want out of queer characters and what gets to be positive representation. “Positive images, we may note, too often depend on thoroughly ideological conceptions of positive (white, middle-class, clean, law-abiding, monogamous, coupled, etc.)” Laura’s character rejects the idea that positive representation of queerness has to be those things; representation of Black female masculinity is such an important subversion from the power and respect that is glued to images of white male masculinity. She holds with power and strength her identity as butch lesbian of color: she is tough, self-assured, popular with femmes, and uninterested in what anyone thinks about her. She is also not diminished to those qualities alone. She is sensitive, intelligent, complicated, she takes her life seriously and has a thoroughly explored, trusting and deep friendship with Alike.Without the moments of vulnerability and openness I described, Laura may have been passed off as a side character, and therefore reduced to some of her more surface level qualities. The times in which stereotypes are negative are when they are diminishing and when characters are not allowed real depth and character development. Halberstam explores the most common queer media stereotypes, “the butch” and “the queen,” pushing back on the assumption that when we encounter butches and queens we are encountering a homophobic narrative. “It is important to judge the work that the stereotype performs within any given visual context-accordingly, if the queen or the butch is used only as a sign of that character's failure to assimilate, then obviously the stereotype props up a dominant system of gender and sexuality. But often the butch or the queen exceeds the limits of representation imposed by the law of the stereotype and disrupts the dominant systems of representation that depend on negative queer images." Butchness, framed simply as a stereotype, denies it any validity as a true and authentic identity.

Laura’s character is a strong example of positive queer representation because she owns her identity and breaks down walls that are so often formed around characters like her. Her character owns a stereotype without presenting it as a failure to be more. The problem with representation in film is that certain characters are not afforded the opportunity to display their “more”. Framing stereotypes as a form of negative representation can be a dangerous narrative. Leaving butchness out of queer stories to avoid stereotypicality depends on butch identity as a negative queer image. Instead of rejecting stereotypes wholly, we should be doing work to make sure we give our minority characters the opportunity to be known fully, to have flaws, and to still be cared about.

Works Cited:

Halberstam, Jack. Female masculinity. Durham (Grande-Bretagne): Duke University Press, 2018.

@theuncannyprofessoro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

How did they figure out that the music was a form of hypnotism?

They Cloned Tyrone

They Cloned Tyrone is a sci-fi mystery drama that follows the story of a drug dealer named Fontaine, who discovers a shocking conspiracy that his entire neighborhood is a part of. Starring John Boyega as Fountaine, Teyonah Parris as a sex worker, Yo-Yo, and Jamie Foxx as a pimp named Slick Charles, the film follows Fountaine and the gang as they try to figure out the truth while finding themselves sinking deeper into the rabbit hole of lies and secrets spread farther than they’d imagined. Fountaine, who was shot in a drive by shooting, came back the next day as if nothing had happened. Slick is shocked because he saw them murder him and immediately knows something is up. When they go to get Yo-Yo's help, they are led to an abandoned house where they find an underground lab where these scientist are running human cloning experiments. This is where they find Fountaine's dead body, the one that Slick had seen the day before.

Fountaine realizes that he is a clone and that the government is surveilling all of Glen, the fictional town in which they live. Slick finds a white powder in the lab which he figures out if being put in the chicken they eat, the hair relaxer at the salon, and in the juice they give out at the communion. Along with this, the music is also a factor of hypnotism against the black community.

In the end it is revealed that the government has made clones of most people in the community of Glen, specifically people like Fountaine and Slick, who are drug dealers and pimps, in order to damage the well being of the people. It is revealed that these simulations are running in multiple cities around the U.S. including L.A, Chicago, and Detroit(all cities with majority Black populations). The ending shows that Fontaine, Yo-yo, and Slick are nowhere near finishing what they started. The movie deals with topics such as free will, community, and personal responsibility. They indirectly address issues that the government has set up against the black community, such as gentrification, the crack epidemic, and police brutality.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think the characters name represent something in particular? Or are part of a theme of sorts?

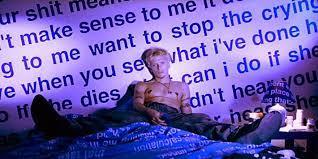

Race in the Imaginary: Nowhere (1997) dir. Gregg Araki

"L.A. is like... nowhere. Everybody who lives here is lost. " -The opening quote of Nowhere

"In general, these films worry that the most violent and degraded acts are possible to those who do not inhabit a home or homeland." -Helen Addison Smith, "E.T. Go Home: Indigeneity, Multiculturalism and ‘Homeland’ in Contemporary Science Fiction Cinema"

Gregg Araki describes his film Nowhere as "Beverly Hills 90210" on acid. Nowhere follows a number of uniquely-named, all somewhat inter-connected teenagers (Lucifer, Dingbat, Egg, Jujyfruit...) in Los Angeles over the course of one day as they engage in an aimless cocktail of drugs, sex, polyamory, BDSM, and parties. The world of the film is in constant flux between reality and fantasy (and it is very, very, very queer). Everything is extremely heightened: there are lengthy, gratuitous sex scenes, a seemingly unlimited access to space, an abundance of drugs, and vast, artistic bedrooms that real teens would only dream of.

In my interpretation, the film's world is an external representation of the teens' imaginations and their feelings of an endless, indestructible youth. While this world is a step above reality for the viewer, it is real to the characters. However, this overindulgence is not without it's consequences. The first half of the film is a sort of queer, sex-positive utopia seemingly free of prejudice in which the teens can have sex with whoever they want, go wherever they want, and so on. This all seems to crumble in the second half of the film, as the teens' endless consumption unravels into overdose, sexual assault, suicide, violent fights, and broken hearts. Araki does not seem to be prudish or critical of this queer nomadic lifestyle, though. He seems to posit that this imaginative world is sadly incompatible with the "real world" of capitalist society at the turn of the century.

Now for the sci-fi. Unbeknownst to every character except Dark, the day on which this film takes place is sort of Judgement Day; the last "normal" day before aliens come to take over the planet.

Dark is the main character of the film, and offers some narration through diary entries and videos he takes of himself and his friends. He is played by James Duvall, a multiracial actor. Dark becomes increasingly unhappier as his girlfriend Mel spends more and more time with her girlfriend Lucifer, who he hates. He grows weary of their indulgence sexually-open arrangement, simply wanting to fall in love and be committed to one person that will anchor him in a world he feels lost in. As he gets more disconnected from Mel, he finds himself infatuated with Mongomery, a boy who goes to school with the teens but who Dark knows little about.

youtube

At the same time as Dark's discontent with his lifestyle grows and he finds himself falling in love with Montgomery, he sees a bunch of giant alien creatures roaming around the city, abducting people. Dark is the only character able to see these aliens, which seems to be no coincidence alongside the fact that he is the only character verbalizing any anxiety about the future and the teens' lifestyle. In one diary entry, he says: "I feel like I’m sinking deeper and deeper into quicksand, watching everyone around me die a slow, agonizing death. It’s like we all know, way down in our souls, that our generation is gonna witness the end of everything. You can see it in our eyes."

In the final scene of the film, Dark returns home after an empty night of partying and a fight with Mel. Montgomery appears at his window and tells Dark that he was abducted and tested on by the aliens. The two boys lie together on Dark's bed and confess their love, promising to never leave each other. Just when it seems like Dark has found what he has been longing for, Montgomery goes into a violent coughing fit and explodes, leaving a bug-like alien in his place that crawls out of Dark's room, and the movie ends.

youtube

While the aliens in Nowhere are not necessarily representative of a racialized Other according Addison Smith's analysis of Sci-Fi films, the impending doom of an alien invasion and Dark's isolating anxiety is quite in line with Addison-Smith's reading of home and homeland. Araki's identity as Japanese-American director and Duvall's as a multiracial American actor are factors in this reading of the film. Since this film is thus told from a mixed/multiracial perspective, the its anxiety is not surrounding the (white/Western) fear of "losing" a home to outsiders, but the fear of not belonging to any one home in the first place.

Addison-Smith writes:

"For many people in self-avowedly multicultural nations such as the United States, their status as migrants, be it forced or economic, recent or later generational, means that 'home’ has become a complex, multiple and sometimes fraught notion. That such multiple belongings to place is not confined to recent migrants can most immediately be seen in the labelling of many ethnic groups through the joining of two place names (African—AmericanJapanese-American)" (28).

Araki uses Los Angeles as an unstable home in this film (note the opening quote at the top of this post). He plays upon the notions of transplants to the city, and the stereotypes that the city and its inhabitants are vain and superficial. The characters move throughout the city at will, with no connection to any particular space. Actual homes are places of confinement and depression (both the suicides in the film occur in character's bedrooms).

I read that Dark's ability to see the aliens is a representation of his sense of displacement and anxiety for the future. When Montgomery enters his room and the two share an extremely intimate, tender moment, his room finally begins to feel like home, rather than its previous role as a space for his lonesome brooding and masturbation. But when Montgomery explodes as is replaced by an alien, Dark's vision of home and someone to share it with also figuratively blows up in his face; home feels impossible.

Finally, Montgomery's objectification by Dark's infatuation and his identity as a white queer man seem to be an inversion of both romance and Sci-Fi tropes. Montgomery seems to occupy both the role of the "Manic Pixie Dream Girl" in Dark's desire to be saved by him, and the racialized alien Other in his mysteriousness and his constant affiliation with the aliens. Addison-Smith writes, "An alien is easy to identify, and particular judgements about them are thus easily drawn from their appearance alone, so rooting their ‘racial nature' in their biology" (27). Montgomery definitely stands out in this world. He has different colored eyes, is always dressed in white, appears to Dark miraculously by a sign that reads "God help me," and, unlike very other character, is quiet and keeps to himself. He is alien and even an angelic figure to Dark, a unique representation against Addison-Smith's notions of the racialized alien as either invader or teacher.

The entire movie Nowhere is on Youtube! I think it's really great, but there's a ton of trigger warnings (sexual assault, drug abuse, suicide, eating disorders, physical assault, gore). The quality is also very bad. Proceed with caution.

youtube

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think that a more nuanced portrayal of the film could acknowledge the complexities of community within a disadvantaged environment?

Roundtable 2: Race in the Imaginary and Attack The Block (2011)

youtube

Attack The Block (2011), directed by Joe Cornish, is a sci-fi film that takes place in South London, and follows a group of trouble-making teenagers who must defend themselves and their apartment complex from extraterrestrial beings. The film begins with the group of teenagers attempting to rob an innocent woman, but their attempt is cut short when something falls from the sky, and lands in a nearby car. Once the woman runs off, the boys go to investigate the car, and stumble upon an alien creature who lunges at them. Originally, it seemed as if the villains were the teenagers, however the landing of the alien establishes the real danger of the story. After they take off the bandanas they had obscuring their faces, and we get a glimpse at their comradery, it's obvious that they are just children.

The boys' failed robbery from the beginning comes back to haunt them, as the woman, Sam, contacts the police to find them. Now, not only does the group have to run from aliens, but the police as well. As the group runs for their lives from aliens, two police officers manage to grab hold of the group's "leader", Moses, played by John Boyega. This is one of many times that the police chase after them, as if they are the aliens, rather than catching the actual aliens that are killing civilians. Here, a comment is being made on the fact that teenage boys of color, specifically Black boys are disproportionally sought after by law enforcement. Moses even goes, to say "I reckon, the Feds sent them anyway. Government probably bred those things to kill black boys. First they sent in drugs, then they sent guns and now they're sending monsters in to kill us”, showing that even in a world where rampaged aliens are killing humans, children of color are seen as the threat.

Most of the film takes place inside, or just outside of a giant housing project in South London, known as, “The Block”. We learn that this is where almost all of the boys live, and a place they feel is their duty to protect, often stating "nobody fucks with Block"(7:09). The building is akin to an eery, futuristic fortress, however it is a clear home for the boys. Though the boys have different personalities, and we get brief glimpses into their differing home lives, The Block marks a universal place of belonging for them. A place where identity is characterized by protecting one another from the impending threats of aliens and law enforcement, both of which have no regard for the boys as people. Though they are seen merely as thugs by law enforcement, the movie works to bring humility to them through giving depth to their personalities, and addressing the socioeconomic context of their lives.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

How much do you think the fim relied on "otherness"? Do you think the films reliance on "otherness" limits the exploration of more nuanced forms of oppression that could exist within both Draag and Om societies?

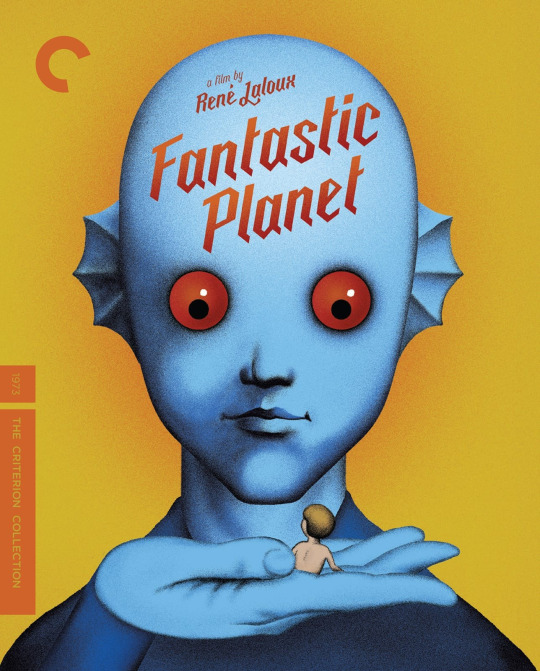

La Planète Sauvage (1973) Race in the Imaginary

René Laloux’s La Planète Sauvage (1973), an experimental animated science fiction art film, is as strange as it is dense with implications. The politically charged dissonance of psychedelia combined with the film’s Dali-esque surreal cutout stop-motion animation universe, realized by French avant-garde artist Roland Topor, has solidified this film as a seminal work of animation and a cult science fiction feature. The film is set in the hallucinatory landscape of the planet Ygam, where gargantuan blue humanoid creatures called Draags who rule the planet enslave humans (called Oms–a play on the French homme)--Terr, an Om who has been kept as a pet since Traag children killed his mother in his infancy escapes from his child captor and bands together with a band of radical escaped Oms to resist the Draag regime and impending genocide. The film is markedly allegorical for its use of imagined alienness to establish otherness and marginalization, and the techniques the Draag use to subordinate the Oms evoke historically significant racist discriminatory practices. Simply, it feels like a movie that is bluntly about something beyond what it appears to be, and the slight heavy-handedness of its messaging reifies its goal of engaging in racial discourse.

The racial politics of Fantastic Planet are strange in that the broadness of the trenchant sociopolitical commentary imminent in the dynamic between oppressor and oppressed has led critics to draw comparisons between the plot and the narrative around “animal rights” and the (mis)treatment of domesticated animals, yet the human-ness stitched into the film’s fabric positions it as a text specifically interested in the ways humans create divisions among themselves. The Draags and the Oms, despite their vast difference in physical size, do resemble one another and take on different forms of the corporality of a human being, and for this reason and many others, Fantastic Planet seems to be a film about how we could recognize ourselves in one another and still splinter into factions and enforce senseless violent domination.

Terr’s captor, a girl named Tiwa, has given him a collar to control him as he attends “school” with her, which involves her wearing a headset that transmits facts into her brain, and a defect in his collar inadvertently allows him to learn the same knowledge as Terr, knowledge he ends up using to save the Oms. Intelligence is the gateway to capital in Ygam and the Draags are highly intellectualized beings who pride themselves on their inborn wisdom and biological superiority that allows them to far outdo the meager Oms in their knowledge–the film comments on the complications of the racialized bioessentialist understanding of knowledge that would posit that being smart, and subsequently having value, is a fixed innate biological trait. The Oms navigate the world through cunning, outwitting the Draags practically in ways they might fail to do so intellectually and the Draags and Oms counter one another in the film on what “counts” as knowledge: the Draags favor transcendental meditative practices that imbue them with highly complex perspicuity, whereas the Oms argue that their knowledge is more useful for the ways it enables them to survive despite their circumstances. The Oms are made alien not only through their physical inferiority but also because they exist in a society that was not built for them. Fantastic Planet depicts an idea of home that is stringent upon exclusivity and requires technical superiority to belong; shoring up racial politics, Fantastic Planet deploys a social constructionist standpoint that colors these divisions as the products of structural forces benefitting only those who erected them.

youtube

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think Mace's character solely serves as a narrative tool for Lenny's development?

Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995)

Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995) is a science fiction thriller set in Los Angeles during the last two days of 1999. With the general consensus being that the end of the world is imminent: Los Angeles has devolved into a warzone of debauchery, violence, and crime. The film centers around ex-cop Lenny, who deals SQUID devices on the black market. SQUIDS are illegal devices that record peoples’ physical sensations and memories from their cerebral cortex onto a mini CD disc that allows them to be played back and experienced by anyone.

Lenny’s ex-girlfriend Faith’s friend Iris ends up recording police murdering black rapper and activist Jeriko One. The audience has only briefly been introduced to Jeriko via a speech he gives on television protesting the police state that Los Angeles has fallen into and pushing for peace. Since Jeriko’s character is not further developed before he is killed, he exists as more of a symbolic placeholder for all of the innocent black people that police have murdered. Iris is then chased by police but ends up getting the tape to Lenny before she is brutally raped and murdered. Lenny and his driver/bodyguard/friend Mace (who is also in love with him) then have to run from everyone who’s trying to kill them and Mace gets the tape of the murder to the police commissioner.

It’s interesting that even in this apocalyptic, end-of-the-world setting, racially motivated violence and police brutality are still prominent. Bigelow has discussed in interviews being motivated to begin production following impactful incidents in the 90’s such as the Lorena Bobbit trial and the Rodney King verdict and the riots that followed in 1992. Multiple of the characters in Strange Days are overtly racist (ie. the cops/murderers), but more subtle racism also permeates throughout. When trying to figure out how to get the video of Jeriko’s murder to the public, Mace and Lenny go to Lenny’s “friend” Max (who will turn out to be an awful person) for help. Max says simply that Lenny and Mace should not show the tape because there will be riots. In this moment Max is willing to silence the story of police murdering a black man to avoid causing a more than warranted uprising.

Bigelow seems to have intentionally sought to explore the intersection between race and gender as she stated that she created Mace’s character to examine "valuable connections between female victimisation and racial oppression." Mace proves to be stronger and more confident than Lenny; she repeatedly saves their lives and gets them out of tricky situations, yet she is still reduced to the role of his bodyguard/driver, and not given much of a story outside of Lenny’s world. At one point when they are in the car, she points out this dynamic saying “driving Mr. Lenny,” a reference to the film Driving Ms. Daisy (Bruce Beresford, 1989). Mace is additionally in love with Lenny because he stepped in and helped her take care of her son when the kid’s father was no longer around. Despite Mace being a strong, smart, and badass, black woman, her story is somewhat reduced to being the white man’s sidekick. She is also in love with Lenny for the entire film and when they eventually kiss at the end, it feels like she has now only existed to be his love interest.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

This was such a good analysis, I haven't seen this movie but now I definitely want to watch it. There are not too many lesbian movies out there and rarely any containing non-white actors, so I am excited to watch this one!

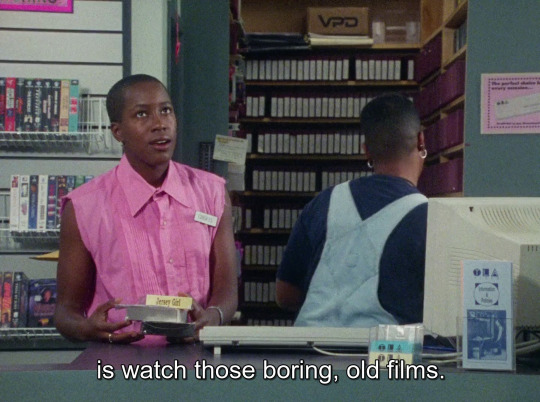

The Watermelon Woman: Queer representational strategies as possibility

Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996) made history as the first feature film written and directed by a Black lesbian–but the film knows this and extensively explores its appellation as the “first of its kind,” a title Dunye simultaneously treats with frustration and reverence. It’s strikingly self-aware, funny, and inventive, a semi-autobiographical story about Cheryl, a video store clerk and chronically single filmmaker who decides to make a documentary on a mysterious Black actress from the 1930s pigeonholed into playing “mammy” roles who appears in the credits of a film called Plantation Memories simply as “The Watermelon Woman.” It’s a movie about movies! “I am a Black lesbian filmmaker who's just beginning,” Cheryl says, and here the thesis of the movie exhumes itself. The text demonstrates a preoccupation with the power of identity as a representational strategy through imagery and insists on its existence, the Black lesbian gaze resisting hiddenness behind the camera and crafting a visible narrative powered by the excavation of archival memory, the straddling of truth and representations of truth, of real and imagined. Dunye’s filmmaking mirrors her own life while the fictionalized version of herself seeks her own image in the black-and-white static of footage nearly lost to history. The Watermelon Woman chronicles the myriad of interconnected dynamics between art and real life–its awareness of the ways it is speaking about and to itself is demonstratively pointed, with Cheryl often speaking directly to the camera about her project and desire to tell Fae’s story.

Fae Richards, the eponymous Watermelon Woman, symbolizes the Black queer archive that future generations of Black queer filmmakers like Cheryl strive to hold within their canon, and as Cheryl interviews subjects for her documentary on Fae and digs through archives she finds proof not only of Fae’s existence but of her queerness¹. She discovers that Martha Page, the white director of Plantation Memories, and Fae were in a relationship, all the while navigating her own dating life, getting entangled with a white video store patron named Diana, much to her best friend Tamara’s dismay. The ways Cheryl’s relationship with Diana parallels Fae and Martha’s excavates the possibilities and challenges of “race relations” within queerness and the ways white lesbianism often possesses an objectifying curiosity with Blackness. The film’s theoretical standpoint as a piece of media that presents a representational theory of Black queerness pointing out gaping holes in the so-called canon is made imminent by some of its casting choices–cultural critic and infamous haver of weird opinions Camille Paglia appears as a parody of herself and a mouthpiece for white feminist film theory offering a misguided take on the “mammy” sterotype, and love interest Diana is played by Guinevere Turner, cowriter and star of the 1994 lesbian film Go Fish. The Watermelon Woman theorizes that sexuality and race are mutually constitutive and through the production and reception of representational imagery this interrelation is complicated by the relationship between the creator and the recipient of an image–Cheryl is a lover of film as much as she is a filmmaker and a large portion of her desire to tell stories about the complexity of being a Black woman who is many things at once comes from her desire to consume these stories.

Jack Halberstam’s “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film” bifurcates queer imagery into “positive” and “negative,” necessarily locating “butch” as a visual identity located in media representations in one of two pathologies². Butchness in film is often leveraged to be emblematic of non-normative female sexuality in a way that is easily visually understood, and as a result, butch lesbians in film have more often than not functioned to be objects rather than subjects of inquiry. Halberstam posits that the debate around positive and negative images often returns to early feminist film criticism calling for “positive representations,” categorically rejecting depictions that could be received in their full complexity as anything other than “good.” Halberstam complicates the idea of a positive image by postulating that this desire for queer imagery imbedded with messaging that campaigns for itself places “the onus of queering cinema squarely on the production rather than the reception of images.” The Watermelon Woman explores how cinema is queered both through the production and reception of images; Cheryl watches Plantation Memories for the first time, she reads the queerness in it and it becomes a queer text because of her viewing, then when it is revealed that The Watermelon Woman and the film’s white director were in a relationship, her read is validated. Cheryl’s onscreen presence as a butch lesbian is overtly queer and her and Tamara’s open discussion of lesbianism as well as an intimate sex scene between Cheryl and Diana underscore this film’s goal of moving beyond the implicit in representation, further informing the lesbian lens with with Cheryl uses to analyze and interpret films like Plantation Memories.

Plantation Memories is not a real film, but it might as well be as it represents the startling politics of race films of its time where the white Scarlet O’Hara-type starlet weeps in the arms of the nurturing Black woman with such vigor that it’s hard not to believe in its existence. The consequence of the effects films like it produced continue to be felt in strategies of representation and Fae Richards does not represent an easily “positive” image of queerness–instead occupying a space in the troubling tradition of the racialized dominant images of Black women in film–yet Cheryl recognizes herself in Fae’s performance partially because it is so fraught. She identifies in her relationship with Diana a similar dynamic to Fae Richards and Martha Page, who only cast her lover in highly stereotyped and racially singular roles, where her lesbianism and Blackness are at slight odds with one another when in a relationship with a white lesbian who can relate to her based on only one of those central tenets and displays a voyeuristic and ultimately isolating interest in the other one. The Watermelon Woman argues for complexity beyond “positive” and “negative” imagery and constructs a Foucauldian reverse discourse where negative imagery can be positively productive when viewed critically and rethought. The film invests in the prospect that art can be a two-way conversation and that by beholding representational images, we project our possibilities onto it. The image on the screen dims and the reflection of the audience is left peering back at itself--Dunye holds onto this moment and treats it with tenderness, imbuing this empty space with hope.

@theuncannyprofessoro

Ratnarajah, Anoushka. “Indisputably Real: Cheryl Dunye’s the Watermelon Woman.” Out On Screen, August 6, 2021. https://outonscreen.com/blog/2020/news/indisputably-real-cheryl-dunyes-the-watermelon-woman/.

Halberstam, Jack. Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film" In Female Masculinity, 175-230. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822378112-008

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was nice to see in a movie a women that represented so many positives, smart, powerful, funny, charismatic, etc. She was easy to like and something we don't see too much of! I enjoyed getting to watch her work really hard but also live!

Lionheart Viewing Response

Lionheart (2018) follows Adaeze's journey to prove herself and take over her fathers company after he develops some detrimental health problems that force him to take a step down. Lionheart represents a professional, driven, intelligent and capable Nigerian woman, which is a step forward for positive representation. Adaeze is capable and deserving of the role she she plays in a very male-dominated world and industry. In her piece, "Signs of Femininity, Symptoms of Malaise: Contextualizing Figurations of ''Woman'' in Nollywood," Jane Bryce quotes Adeleye-Fayemi. She states that "film and television are ruled by the "mirror-image paradigm," which dictates that, in order for audience expectations to be fulfilled, women are portrayed as either "powerful and dangerous" or "long-suffering" and "in this 'either/or' way of portraying women, women are shown not just as society perceives them, but as society expects them to be"." I think Adaeze is portrayed as a person to take seriously and a force to be reckoned with, while also holding complexity and lightheartedness. We see different sides of her in her relationship to her family and her relationship to her work. She is not an overly serious figure. She is scheming with her uncle and having ridiculous, comedic interactions while also holding her own and ultimately leading the company to success.

@theuncannyprofessoro

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was great to see a movie that represented a woman wanting more then just a successful love life. Being able to see a successful women achieve her goals was inspiring and not very common in Nollywood or honestly the film world in general.

Lionheart

Lionheart is a Nollywood film that goes against all of what is expected in a typical Nollywood representation of women. Lionheart centers a successful woman who works in a top position at a transportation company. She is self-assured, confident, and independent. In Jane Bryce's article "Signs of Femininity, Symptoms of Malaise: Contextualizing Figurations of 'Woman' in Nollywood," she writes of patterns of women being overly sexualized or placed in a phallo-centric gaze in typical Nigerian cinema. Lionheart subverts these expectations by focusing on the principal character's success and fight to keep her family's business afloat. When a man makes sexual advances towards her, it is quickly dismissed. In the end of the film, the happy ending is not her flourishing love life but the success of her goals.

@theuncannyprofessoro

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really liked how you brought up how she was able to connect to others not just her own age. That seems like something that would be very important and useful in a tribe, espically a leader. She also was able to sustain relationships well, like you mentioned being able to mend her relationship with her grandfather with no compromise was a huge success.

Paikea in Whale Rider

Whale Rider’s Paikea is empowering as she is resilient and mature, shown by her drive and effort to become an effective leader despite her grandfather believing the contrary just because she is female. Paikea is “closely associated with the sea and its inhabitants, with tribal ancestors and gods, and with a wisdom that can generate reconciliation between the sexes, between generations, and between humanity and the earth” (du Plooy 5). Paikea has a deep connection with the sea, especially whales as seen by her inability to leave with her father and then riding the whales towards the end of the film. Paikea is also wise as she overall understands the actions of others around her but also lives to ensure that she is able to gain necessary skills and knowledge. Paikea also brings together different generations of her tribe. As a child, she already has relationships with other children but then extends this to her relatives of different generations. For example, Paikea bonds with her uncle when trying to learn how to use the Taiaha. Paikea also mends her relationship with her grandfather but doesn’t have to compromise in doing so. Paikea makes a remarkable role model and leader.

@theuncannyprofessoro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I honestly didn't think about all the symbolize the rope had in this scene so I think it is really interesting that you brought it up. There are so many times throughout the movie where Paikea helps someone, or shows her worth but is continually not appreciated or noticed. This scene in particular made me feel so sad as she was so overlooked.

Whale Rider Response

For this week’s response, I’ll write about the scene where Paikea ties the rope back together, a scene where she proves herself valuable, yet she continues to be denied. He had just explained how the threads of the rope twisted together are the strength of their ancestors, and to demonstrate, he puts the rope in the engine to start it, and it breaks immediately, but Paikea is successful in her repair. In their article “Anthropocene Terror in Two Girl-Centered Narratives: The Leitmotifs of Mythological Time, Colonization and Monstrosity in the Films Whale Rider and Moana,” Belinda du Plooy writes that the film provides an “example of the changing role of, particularly female, youth in contemporary societies and the paradoxical complexities situated at the nexus where popular pedagogy and critical pedagogy merge and conflate” (7). In this early 2000s film, Paikea fights the tradition of only sons being able to succeed chiefs, even if his next direct descendant is a woman. I really loved this scene because she quietly ties the rope back together - not only repairing the motor, but making a symbolic statement that she understands the strength of her ancestors and has the ability to lead her community; she is capable of being chief, despite tradition, despite being a girl.

@theuncannyprofessoro

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think that focusing solely on District 11 might overshadow the possibility that Collins could have been creating a more nuanced commentary on race throughout Panem?

Race in The Hunger Games

The Hunger Games (2012) is a film adaptation of the critically acclaimed novel series by the same name, followed by three more movies and a prequel movie that came out this year. The basic concept of the story is a nation called Panem that has been divided into districts, each responsible for a specific need in the nation (electricity, coal, fishing, transportation, etc.). In districts 1-12, number 1 is the richest district while 12, the poorest district, is the home to main characters Katniss and Peeta. Most of the characters in the films are white with the exception of a few characters. Even in the crowd shots in the film the background actors are majority white.

District 11 is a district made up of mostly black people, with their focus on agriculture. It is said to be reflective of the American south, but Collins received a lot of criticism for putting all the black people in one district and having their focus be crops because it is reflective of slavery. Two Hunger Games tributes come out of District 11: Rue and Thresh, brother and sister. Rue forms a strong bond with Katniss, but eventually dies, which is a driving force for Katniss to rebel against the Capitol later on. When Rue dies, District 11 revolts, and are met by violence from the “Peacekeepers” which are the story’s representation of police.

Dividing the nation into districts is how Suzanne Collins emphasizes the different identities and different opportunities; the richer districts receiving better opportunities and treatment from the government. But, Collins has received criticism for putting social class/monetary value as the central cause for oppression in this futuristic society, as some critics have argued the emphasis on class complies with the liberal tendency to reduce “class to inequality in order to deflect attention from racial disparities.” Even so, placing all the black people in one district and putting them in the second-poorest district is quite weird. If Collins’ point was being realistic or “color-blind,” it would make more sense to make all districts ethnically diverse. This immediately ostracizes the black characters as the other characters and the film’s audience associates their race with their social standing.

Since District 12 is the poorest, it receives little attention from Panem’s government. But, District 11 is overly patrolled by the “Peacekeepers,” reflecting the over-policing of black communities in the U.S. “During the Games, Rue tells Katniss that the District 11 citizens are all forced to work on the farms for the harvest and are whipped for resisting or stealing the food. Katniss realizes that perhaps there are benefits to being the poorest district, since the Capitol ignores most of what goes on in District 12. What she has stumbled onto is white privilege: she may be poor, but her skin color gets here more freedom than Rue gets. This important detail, however, receives almost no attention in the book and is completely left out of the film.” (A Game of Race, Ian Pultz Earle). The technologies/lack of technology that separate district 11 from others are the surveillance state that they live in which is very different from district 12 which is completely neglected by the government.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critical Film Analysis: The Breadwinner

The Breadwinner is a 2017 animated drama film based on the young adult novel of the same name by Deborah Ellis. The story centers around Parvana, an 11-year-old girl living in Kabul, Afghanistan under Taliban rule in 2001. The Taliban has imposed strict limitations on women's freedoms. Parvana's world is upended when her father, a former teacher and the family's breadwinner, is wrongfully arrested. Faced with the inability for women to work or freely go about in public, Parvana makes a courageous decision. She disguises herself as a boy to support her family. Entering a world unseen by her before, Parvana experiences both newfound freedoms and dangers. She also finds solace in weaving fantastical stories, mirroring her own struggles. The film follows Parvana's journey as she tries to find her father and keep her family afloat. In my video essay I touched on how Parvana’s story is a powerful exploration of gender performance under oppression, viewing it through the lens of Judith Butler's “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion.”(1) Now I will delve deeper into this analysis, but will also draw upon additional feminist and gender film theory to incorporate additional theoretical perspectives and enrich our understanding.

In Judith Butler's seminal work, “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” she argues that gender is not a fixed identity or an innate biological reality but a performance, a set of cultural expectations we embody. We learn and embody gender through social norms and expectations. The Breadwinner beautifully showcases this concept through Parvana's act of disguise. By adopting a masculine presentation, she disrupts the Taliban's rigid gender binary, demonstrating how gender is a constructed identity, not a fixed essence. In my video I also point out the intersection of race and ethnicity with gender performance. The film masterfully portrays the complexities of navigating gender performance within a specific racial and ethnic context. Pashtunwali, the Afghan cultural code, emphasizes male dominance, which the Taliban weaponizes. Parvana, by adopting masculinity, disrupts this system. However, it's crucial to acknowledge the limitations of her performance. Unlike white women who might "pass" as men with more ease, Parvana's ethnicity and the constant threat of exposure add another layer of complexity.

My video essay highlights the significance of Parvana’s storytelling as a form of resistance. By weaving fantastical tales featuring strong female characters, Parvana not only provides solace for her family but also subverts the Taliban's oppressive message. While my video focuses on Parvana is act as a form of resistance, it is important to acknowledge the psychological toll it takes. Scholars explore the concept of embodied identities, highlighting how prolonged performances can shape our sense of self. Parvana's constant fear of exposure, the strain of living a double life, all contribute to the film’s emotional depth. It reminds us that resistance comes at a cost, with potential psychological consequences that deserve exploration.

Laura Mulvey's work, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” posits the “male gaze” in cinema, where the camera and narrative focus on the objectification of women for the male spectator's pleasure, “The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly.” (2) However, the Breadwinner challenges this notion as Parvana's story isn't framed through a male gaze; it's hers. Parvana actively resists this gaze, disguised as a boy, she navigates a male-dominated world, observing and critiquing its power structures. We see the world through her eyes, her fear, and her determination to survive. Her fantastical stories, a source of solace for her family, become a form of resistance.

This aligns with E. Ann Kaplan's work in “Is the Gaze Male?”(3) which argues for the possibility of a “female gaze,” a counterpoint to Mulvey's theory. Kaplan's essay critiques the concept of the “male gaze” in cinema, which suggests that films are inherently structured from a masculine perspective. This perspective positions the male character as the active subject, looking at the female character as a passive object of desire. Parvana defies the concept of the male gaze in several ways, the first being that she is the central character, driving the narrative forward through her actions and decisions. Parvana also holds a duality of roles as she adopts a masculine persona and challenges the societal norms that restrict females disrupts the film's gaze, making it unclear who is looking at who. Parvana's strength and determination counter the stereotypical image of the passive female as she actively resists the oppressive forces around her. Parvana's character in “The Breadwinner” offers a complex critique of the male gaze, while the film acknowledges the constraints placed upon females, Parvana's defiance and strength challenge these limitations. Through her journey, the film suggests the possibility of a more nuanced gaze in cinema, one that celebrates female agency and resilience.

Furthermore, bell hooks, in her work “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,”(4) emphasizes the importance of considering race and ethnicity when analyzing representation. In this piece hooks focuses primarily of Black women and although there are no Black characters in “The Breadwinner,” hooks' concept of the “oppositional gaze” encourages critical viewing regardless of race. Parvana's story allows viewers, particularly female viewers, to challenge stereotypical portrayals of women, especially those confined by war and oppression. Parvana doesn't conform to the expectations placed upon young Afghan girls. She actively resists the limitations placed on her and seeks agency through her actions. This aligns with hooks' oppositional gaze, the idea of critical viewers rejecting the male-centered gaze and the limitations placed on female characters. The movie doesn’t shy away from the harsh realities of war and oppression. However, Parvana's resourcefulness and resilience can offer a different kind of pleasure for viewers – the pleasure of witnessing a young girl challenge the status quo. This aligns with hooks' notion of finding pleasure in deconstructing dominant narratives. By applying bell hooks' concept of the oppositional gaze to Parvana, we can see how the film challenges traditional gender roles and empowers viewers to critically engage with the narrative. While there are limitations in directly applying a race-focused concept, hooks' ideas still offer a valuable framework for analyzing Parvana's defiance and the film's message of resilience.

It's important to acknowledge a potential critique here. While Parvana's performance disrupts the Taliban's power structure, some might argue that it reinforces traditional gender roles. By adopting masculinity to gain freedom, is she simply conforming to another set of expectations? Unlike some narratives where women “pass” as men and achieve complete societal integration, Parvana’s performance is constantly under threat of exposure.

The Breadwinner offers a powerful message about resilience and defiance in the face of oppression. By critically analyzing the film through the lens of gender performativity, intersectionality, and the power of storytelling, we gain a richer understanding of Parvana's journey. This multifaceted approach allows us to appreciate the film not just as a story of survival but also as a commentary on the complex interplay of gender, race, ethnicity, and the human spirit's ability to rewrite the script, even in the darkest of times.By weaving together Butler's theory of performative gender, Mulvey and Kaplan's discussions of the gaze, and hooks's emphasis on race and ethnicity, we gain a richer understanding of the film's message. It highlights the film's engagement with race and ethnicity alongside gender performance, creating a more nuanced understanding of Parvana's resistance. It's through this intersectional lens that The Breadwinner truly resonates, offering a powerful message of hope and resilience.

Work Cited:

Butler, Judith. “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” in Feminist Film Theory a Reader (New York: Washington Square, 1999), 338

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism (New York: oxford University Press, 2009), 715

Kaplan, E. Ann. “Is the Gaze Male?” in Women in Film: Both Sides of the Camera (London: Methuen, 1983), 119

bell hooks, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 309

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

Analytical Application 1

youtube

The culture industry, as theorized by Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, is a branch of capitalism concerned with the mass production of standardized cultural products like movies, music and advertisements. This industry prioritizes profit and the maintenance of the ruling class by churning out formulaic content that reinforces dominant ideologies. The primary goal is to generate profit, not artistic merit; cultural products serve to pacify consumers and maintain the status quo. (1)

Amazon's “Alexa Loses Her Voice” Super Bowl ad can be effectively analyzed through the lens of the Culture Industry theory developed by Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno. First the ad embodies the key main aspect of this theory, standardization and mass production. The ad relies on celebrity cameos which are a staple of Super Bowl advertising. This predictability and focus on big-name recognition exemplifies the standardized approach of the culture industry. In this ad it is obvious that the company, Amazon is focusing on profit over content. The humor revolves around the disruption of Alexa’s functionality, a core selling point of the product. The focus is on entertainment value and grabbing attention, not on showcasing the actual functionalities of Alexa which prioritizes entertainment over genuine product exploration. Next the ad reinforces dominant ideology as it presents a lighthearted and humorous scenario despite the potential anxieties people might have about their smart home technology malfunctioning. I know that I would be pretty freaked out if Alexa not only knew my name but could talk back to me with sass. It downplays any potential dangers or ethical concerns surrounding voice assistants and reinforces the image of these technologies as convenient and seamless. The ad acknowledges the dominance of Alexa in people's lives by portraying a world thrown into chaos by her silence and portrays celebrities struggling with basic tasks without the devices assistance, such as being able to make a grilled cheese sandwich. This reinforces the idea that consumers are dependent on such technologies for even the most mundane needs, potentially creating a “false consciousness” about our own capabilities. In conclusion, the advertisement “Alexa Loses Her Voice” reflects the Culture Industry and utilizes celebrity, humor, and mass appeal while hinting at the potential anxieties associated with our dependence on such technologies.

youtube

Aura, as theorized by Walter Benjamin, is the unique presence and authenticity that surrounds an original work of art. In his piece “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Benjamin defines “the aura as the unique appearance of a distance.” (2) This special quality stems from the work's existence in a specific time and space, including its creation process and its physical location. Benjamin argued that the aura is diminished in the age of mechanical reproduction, “by making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence”. (3) Mass production of artworks through technologies like printing presses and cameras creates copies that lack the singular authenticity and cultural context of the original. According to Benjamin this weakens the artwork’s evocative power and its connection to the viewer. In essence, aura is the unique atmosphere surrounding an original work of art, a quality that is lessened when the work is easily reproduced and disseminated.

The 2018 Super Bowl ad for Tide, “It's a Tide Ad,” offers a fascinating case regarding the concept of aura as theorized by Walter Benjamin and explained above. In the ad the traditional Aura that Benjamin discusses is destroyed. Benjamin argued that the aura of a work of art diminishes with mechanical reproduction. “It's a Tide Ad” blatantly breaks the fourth wall, acknowledging throughout the video its status as a commercial and stripping away any illusion of originality or artistic merit. The humor in the ad stems from disrupting the usual flow of commercials, especially high-budget productions like those featured during the Super Bowl. This self-awareness destroys the aura associated with such productions. The ad prioritizes functionality (in this case clean clothes) over any artistic message or emotional resonance. This aligns with the core purpose of advertising: to sell a product, further distancing itself from the traditional notion of aura associated with art. Tide’s 2018 Super bowl “It's a Tide Ad” is a clever commercial that uses self-referential humor to achieve advertising goals. However, by drawing attention to its artificiality and prioritizing functionality over artistry, the ad dismantles the concept of aura traditionally associated with art experiences. In a way, it highlights the loss of aura in the age of mass advertising and constant information flow.

youtube

The ruling class, as theorized by Marx and Engels, is a small group of elites who hold significant economic and ideological power in a society. They control the means of production, land, factories, etc. in capitalist bourgeoisie societies bourgeoisie, or hold positions of significant influence in other systems. The two theorist describe the ruling class as, “the class which has the means of material production at its disposal, consequently also controls the means of mental production.” (4) The Ruling Class utilizes its control over institutions and resources to economically disadvantage the lower class, thereby strengthening its own position.

Iceland’s banned Christmas ad, “Say hello to Rang-tan,” utilizes the concept of a ruling class to deliver a powerful message about environmental destruction. The ad starts with a seemingly idyllic Christmas scene, a world the ruling class might want to perpetuate as it is one of comfort, consumption, and tradition. However, the arrival of Rang-tan, the displaced orangutan, disrupts this picture of harmony. In this ad Rang-tan represents the victims of the ruling class's actions. Her presence forces viewers to confront the environmental consequences of their consumption habits, a consumption often fueled by the desires of the ruling class. The ad challenges the viewers comfort and complacency, shifting the power dynamic from a carefree holiday to one of uncomfortable responsibility. The ad doesn't shy away from showing the destruction of Rang-tan's habitat, a consequence of actions often driven by the ruling class's insatiable demand for resources. This exploitation, hidden from most consumers, is brought to the forefront, forcing viewers to question the systems benefiting the ruling class at the expense of the environment and its inhabitants. While the ad encourages viewers to fight to save Rang-tan's home and share this story, it stops short of directly addressing the root causes of deforestation, which is often tied to bigger and more powerful corporations (than Iceland) and government policies. This could be seen as a way to empower individuals without alienating the ruling class entirely. “Say hello to Rang-tan” is a powerful critique of the ruling class that is disguised as a Christmas ad. By using a relatable character and disrupting the holiday cheer, the ad challenges viewers to confront the environmental consequences of a system that benefits the privileged few. While the ad doesn't dismantle the entire power structure, it effectively uses the concept of the ruling class to make viewers uncomfortable and question their role in a system that leads to environmental destruction.

youtube

Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs), as theorized by Louis Althusser, are a set of distinct social institutions that appear neutral but function to reproduce and legitimize the ideas and interests of the ruling class. These institutions, unlike the repressive state apparatus (police, army), don't rely solely on force, but on cultural practices and everyday interactions. Althusser says, “I shall call Ideological State Apparatuses a certain number of realities which present themselves to the immediate observer in the form of distinct and specialized institutions.”(5)

John Lewis' Christmas advertisement, “She's Always a Woman,” exemplifies how advertising acts as a tool for Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs) to perpetuate narrow views of gender and family life. The ad portrays a woman navigating various domestic tasks throughout her life. This reinforces traditional gender roles, where women are associated with the domestic sphere. While seemingly harmless, it aligns with the function of ISAs, like advertising, in normalizing specific ideologies. The ad features a single woman on a stereotypical domestic journey. This limited representation excludes alternative lifestyles and reinforces the idea that domesticity is an inherent female trait. However, unlike some blatant sexist advertising, it doesn't explicitly condemn other choices. The ad portrays a comfortable, well-furnished home, showcasing John Lewis products that enhance this lifestyle. This strategy aligns with ISAs by promoting a specific consumerist ideology: that happiness and a good life are achieved through material possessions. The ad doesn't explicitly shame women who don't follow the domestic path. The woman's journey can be interpreted as one of resilience and strength, regardless of the specific tasks depicted. The John Lewis, “She's Always a Woman” ad is a complex case, while it doesn't overtly promote an oppressive ideology, it subtly reinforces traditional gender roles and consumerism, both elements potentially supported by ISAs. However, the ad also leaves room for alternative interpretations, suggesting a less rigid approach compared to some traditional advertising.

youtube

Ideology as theorized by Althusser is a complex system of ideas, beliefs, and values that shapes how people understand the world and their place within it. In capitalist societies, these ideologies can be used to justify the existing social order, often the conditions faced by the working class. This helps maintain the power of the ruling class and minimizes resistance. These ideologies can emerge from various sources, including a group's internal social structures or the external environment.

P&G “Thank You, Mom” is a heartwarming commercial that celebrates mothers and their sacrifices. However, analyzed through the lens of ideology, the ad reveals some interesting underlying messages. The ad portrays mothers as the primary caregivers, handling everything from scraped knees to emotional support. While undoubtedly true for many families, this reinforces a traditional gender role where childcare is primarily a woman's responsibility. The ad emphasizes the emotional labor mothers provide, the invisible work of nurturing and supporting their children. This can be seen as promoting an ideology that undervalues this essential work, focusing on its emotional impact rather than its practical and economic importance. The commercial revolves solely around mothers and fathers are absent from the picture which reinforces a limited view of parenthood, potentially excluding the contributions of fathers or same-sex couples. The ad’s overall message is positive and uplifting, however, it avoids any critical social commentary. Issues like societal pressures on mothers, lack of parental leave, or childcare challenges are not addressed in the commercial. P&G's “Thank You, Mom” celebrates motherhood but does so within a specific ideological framework. It reinforces traditional gender roles and the emotional aspects of childcare, while presenting a limited view of parenthood and avoiding social critique. The commercials power lies in its emotional appeal, but a deeper analysis reveals its potential role in perpetuating certain ideologies about mothers and families.

Work Cited:

Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” Essay. In Dialectic of Enlightenment Philosophical

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Essay. In Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, 665–85. (New York, NY: Oxford Press, 2009.), 669

Benjamin, 668

Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. “The Ruling Class And The Ruling Ideas.” In The German Ideology Vol. 5. N.p.: (Lawrence & Wishart, 2010), 59

Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation.” Essay. In The Anthropology of the State A Reader, 90. (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006.), 92

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

MAC 123 Final

Introduction: